Abstract

Life History Theory (LHT), a branch of evolutionary biology, describes how organisms maximize their reproductive success in response to environmental conditions. This theory suggests that challenging environmental conditions will lead to early pubertal maturation, which in turn predicts heightened risky sexual behavior. Although largely confirmed among female adolescents, results with male youth are inconsistent. We tested a set of predictions based on LHT with a sample of 375 African American male youth assessed three times from age 11 to age 16. Harsh, unpredictable community environments and harsh, inconsistent, or unregulated parenting at age 11 were hypothesized to predict pubertal maturation at age 13; pubertal maturation was hypothesized to forecast risky sexual behavior, including early onset of intercourse, substance use during sexual activity, and lifetime numbers of sexual partners. Results were consistent with our hypotheses. Among African American male youth, community environments were a modest but significant predictor of pubertal timing. Among those youth with high negative emotionality, both parenting and community factors predicted pubertal timing. Pubertal timing at age 13 forecast risky sexual behavior at age 16. Results of analyses conducted to determine whether environmental effects on sexual risk behavior were mediated by pubertal timing were not significant. This suggests that, although evolutionary mechanisms may affect pubertal development via contextual influences for sensitive youth, the factors that predict sexual risk behavior depend less on pubertal maturation than LHT suggests.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Adolescents’ involvement in high-risk sexual behaviors renders them vulnerable to unplanned pregnancies and sexually transmitted infection (STIs) (Eaton et al., 2012). An emerging body of research has investigated this problem from the perspective of Life History Theory (LHT) (Ellis, 2005). LHT, a branch of evolutionary biology, maintains that organisms maximize their reproductive success in response to environmental conditions (Stearns, Allal, & Mace, 2008). Developmental psychologists (Ellis, Shirtcliff, Boyce, Deardorff, & Essex, 2011) and public health scientists (Kruger, Reischl, & Zimmerman, 2008) have identified ecologically induced alterations in life histories as constituting a valuable perspective for understanding adolescents’ engagement in a range of risk behaviors, including sexual risk. LHT-informed studies specify the ways in which environmental factors affect sexual behavior by accelerating pubertal maturation (Neberich, Penke, Lehnart, & Asendorpf, 2010; Negriff, Susman, & Trickett, 2011). The majority of these studies focus on female youth. Studies of boys have yielded less evidence of plasticity; however, community environmental factors have not been investigated. Also, recent research suggests that individual differences in susceptibility to stressful environments may play a prominent role in the effects of context on reproductive maturity (Ellis et al., 2011). To address these limitations, we investigated the influence of community, family, and differential susceptibility processes on boys’ pubertal maturation and subsequent sexual risk behavior.

Life History Theory and Adolescent Development

LHT describes the ways in which organisms allocate time and energy to various activities over their life cycles (Stearns et al., 2008). Due to structural and resource limitations, organisms cannot simultaneously maximize the major life functions of (1) bodily maintenance (e.g., immune function), (2) growth (acquisition of physical and cognitive competencies), and (3) reproduction (mating and parenting). Instead, natural selection has shaped organisms to make trade-offs that prioritize resource expenditures. Many species, including humans, have evolved mechanisms that allow them to “schedule” development and activities (i.e., allocate resources) in a manner that optimizes trade-offs over the life course in response to ecological conditions (Ellis & Essex, 2007). Because both stressful and supportive rearing environments have been part of the ancestral human experience, evolutionary psychologists posit that developmental systems have been shaped by natural selection to respond adaptively to both types of environments.

Life histories can be characterized as “fast” versus “slow” (Ellis et al., 2012). Slow strategies reflect a focus on the future and long-term survival. They include behaviors such as greater parental investment in a smaller number of offspring, delayed parenthood, and long-term relationships. Personality characteristics, such as valuing future rather than present rewards, are associated with this strategy (Kruger et al., 2008). Slow strategies are more common in predictable environments with adequate resources in which life expectancies are relatively long. In these environments, planning for the future and delaying sexual maturation and parenthood allows young people to increase their personal resources to form stable families and provide high levels of care for future offspring. Environmental stability rewards these kinds of strategies with greater survival rates among children. In harsh, unpredictable environments, careful planning and delaying reproduction makes less sense—fast strategies allow individuals to adopt adult roles, including procreation, before they are killed or incapacitated, thereby improving reproductive fitness in the context of poor long-term prospects.

The Environmental Context of Pubertal Maturation, Gender, and Community Effects

The parenting that youth receive is thought to be a primary means of signaling to them the kind of environment with which they will be coping as adults (Del Giudice & Belsky, 2010). Chaotic, low-resource environments characterized by poverty and lower life expectancy are linked to harsh or neglectful parenting styles (Repetti, Taylor, & Seeman, 2002). Harsh, inconsistent, or neglectful parenting signals to youth that their future environments will be difficult and uncertain (Belsky, Schlomer, & Ellis, 2012), steering youth toward “fast” LH strategies. Conversely, nurturing, responsive parenting is hypothesized to lead to “slow” trajectories characterized by delayed sexual maturation. These effects are hypothesized to occur independent of body mass, a robust predictor of sexual maturation (Lee et al., 2010). Parent–child warmth, cohesion, and positivity predict girls’ later age at menarche (Belsky, 2010); conversely, parent–child conflict and coercion predict earlier menarche (Ellis, 2004). Paternal absence and the presence of stepfathers appear to play unique roles in accelerating pubertal maturation among female youth, independent of family relationship quality (Quinlan, 2003). Earlier age at menarche, in turn, predicts earlier onset of coitus, adolescent pregnancy, and elevated sexual risk behaviors in adolescence, including unprotected intercourse and multiple partners (De Genna, Larkby, & Cornelius, 2011; Savolainen et al., 2012).

Studies addressing environmental influences on males’ pubertal timing have been inconsistent. Bogaert (2005) found that father absence at age 14 predicted early puberty for both adult men and women who recalled their ages at pubertal onset. Other studies conducted only with male youth found no association (Belsky et al., 2007b; James, Ellis, Schlomer, & Garber, 2012). These studies, however, considered only family environment factors. Community environments, however, may have direct effects on youth independent of the influence of family relationships. Several studies point to differential sensitivity between male and female youth to stressors experienced in community versus family environments (Kogan et al., 2010, 2011; Ramirez-Valles, Zimmerman, & Juarez, 2002). The influence of stressful communities on male youth’s pubertal maturation remains to be investigated. Recent research also suggests that youth vary in their sensitivity to environmental influences based on individual difference variables such as temperament (Belsky & Pluess, 2009). We thus investigated one such susceptibility factor, a temperament characterized by negative emotionality.

Conceptual Model of Study Hypotheses

Our hypotheses are presented in Fig. 1. We expected harsh, unpredictable community environments to lead to early pubertal timing among male youth directly as well as indirectly by promoting harsh, inconsistent, and unregulated parenting. Early pubertal maturation, in turn, was expected to forecast involvement in sexual risk behavior including an early sexual onset, multiple sexual partners, and concurrent substance use and sexual activity. Consistent with the environmental susceptibility perspective (Belsky & Pluess, 2009), we hypothesized that community and family factors would be predictors only for those young men with elevated levels of negative emotionality.

Multiple, interrelated community dimensions contribute to a lack of resources and a sense of unpredictability. Problematic communities evince signs of social disorder, including dilapidated buildings and other signs of breakdown in the neighborhood infrastructure (Natsuaki et al., 2007). Deviant behaviors, such as crime and gang activity, proliferate in disadvantaged communities, leading to fear and vigilance among residents (Brody et al., 2001). Challenging community environments also evince low social cohesion and a lack of informal social control of neighborhood youth (Sampson, Raudenbush, & Earls, 1997). Social cohesion refers to the strength and supportiveness of ties among neighbors. Informal social control involves the extent to which neighbors collectively monitor youth and respond to behaviors that the community agrees are inappropriate. Studies link these characteristics to precocious and high-risk sexual behavior among youth (Brewster, 1994; Upchurch, Aneshensel, Sucoff, & Levy-Storms, 1999).

Neighborhood influences are mediated in part by community effects on parenting behavior (Brody et al., 2001; Simons, Lin, Gordon, Brody, & Conger, 2002). Disadvantaged communities undermine effective, regulated parenting; this occurs independently of the influence exerted by the economic hardships that predominate in most disadvantaged neighborhoods (Pinderhughes, Nix, Foster, & Jones, 2001). Harsh, inconsistent parenting also predicts early and high-risk sexual activity (Henrich, Brookmeyer, Shrier, & Shahar, 2006; Miller, 2002). We considered three aspects of parenting that we hypothesized would forecast pubertal maturation: harsh parenting, low use of inductive parenting, and low parental monitoring. Harsh parenting predicts conduct problems among youth of both genders (Walton & Flouri, 2010) and pubertal timing among female youth (Belsky et al., 2007b). Inductive parenting involves explaining the reasons for family rules and the consequences of breaking them, which assures youth that parental behavior is not arbitrary. Finally, parental monitoring is robustly associated with youth’s delay of sexual activity (Baker et al., 1999) and avoidance of conduct problems (Simons, Simons, Chen, Brody, & Lin, 2007). From an LHT perspective, low parental monitoring signals a lack of the concern and supervision associated with the opportunity to grow up “slow.”

The sexual risk behavior endpoint includes early sexual onset, numbers of partners, and use of substances during sexual activity. Early sexual onset and number of sexual partners are linked to youth’s risk for unplanned pregnancies and STIs (Baker et al., 1999; Koniak-Griffin, Lesser, Uman, & Nyamathi, 2003). LHT suggests that both factors represent a “fast” reproductive strategy that follows from growing up in harsh and unpredictable environments. LHT suggests that fast trajectory youth will engage in “adult-like” behaviors, such as alcohol use, and pursue generally high-risk lifestyles (Ellis et al., 2011). Concurrent substance use and sexual activity is an example of this type of risk behavior and is linked to a heightened likelihood of unplanned pregnancy, an outcome relevant to life history (Koniak-Griffin et al., 2003).

Consistent with a differential susceptibility perspective, we hypothesized that negative emotionality would moderate the pathways linking community and family environments to pubertal maturation (see Fig. 1). Belsky and Pluess (2009) described the extensive evidence for plasticity in children’s and youth’s responses to environmental inputs, particularly parenting behavior. They concluded that some individuals appear more susceptible to both the adverse effects of unsupportive contexts and the beneficial effects of supportive ones. Identified susceptibility factors include a temperament characterized by negative emotionality. A wide variety of rearing experiences are linked to greater variance in multiple developmental outcomes when children and youth evince negative emotionality (Bates, Pettit, Dodge, & Ridge, 1998; Compas, Connor-Smith, & Jaser, 2004; Wills, Sandy, Yaeger, & Shinar, 2001). Young people who express negative emotionality may have highly sensitive nervous systems in which experience registers particularly strongly (Belsky et al., 2007a). To our knowledge, only one study has examined the association of differential sensitivity to the environment with pubertal timing. Controlling for gender, Ellis et al. (2011) found that, among youth with high sympathetic nervous system reactivity as indicated by cortisol levels, harsh parenting predicted pubertal timing. For youth low in contextual sensitivity, no effects emerged. Informed by these findings, we expect community and family effects on pubertal timing among male African American youth to be evident only for those who express high levels of negative emotionality.

Method

Participants

Hypotheses were tested with data from 375 male African American adolescents and their primary caregivers, who were participating in the Family and Community Health Study (FACHS) (Gibbons, Gerrard, Cleveland, Wills, & Brody, 2004; Simons et al., 2002a, b). Families were selected randomly from 259 census block group areas representing neighborhoods in suburban communities and small cities in Georgia and Iowa. Complete data were gathered from 72 % of the families on the recruitment lists. Those who declined to participate usually cited the amount of time required for data collection as the reason. Of the primary caregivers, 84 % were the youth’s biological mothers, 37 % of whom were married at baseline. The remaining caregivers were grandmothers (6 %), biological fathers (5 %), or other adults (5 %). The caregivers’ mean age was 38 years (SD = 33.21), and their educational backgrounds ranged from less than a high school diploma (19 %) to a bachelor’s or graduate degree (10 %); the modal education level (71 %) was a high school diploma. Mean family annual income was $28,184 (SD = 19,057). The sample was generally representative of African American families in working-class and poor neighborhoods in Iowa and Georgia. Data were combined for both sites when prior analyses revealed no significant differences across demographic categories (Brody et al., 2001).

Study hypotheses were tested with data from the baseline assessment, a second assessment occurring 2 years later, and a third assessment that occurred 5 years after baseline. Youth’s mean ages were approximately 11 years at baseline (10.6; SD = .63), 13 years at the second assessment (12.6; SD = .73), and 16 years at the third assessment (15.7; SD = .78). Of the youth who provided data at baseline (411), 87.6 % (350) provided data at age 16. Attrition was not associated with participants’ demographic characteristics or any study variables. For more information on the sample, see Simons et al. (2002a).

Procedure

African American research staff conducted two home visits, each lasting approximately 2 h, with each family for data collection. During the first baseline visit, self-report questionnaires were administered in an interview format conducted privately between one participant and one researcher. Questions appeared in sequence on a laptop computer screen, which both the researcher and participant could see. The researcher read each question aloud and entered the participant’s response using the computer keypad. For sensitive questions, such as those concerning sexual behavior, the participants used a remote keypad to input their answers.

Measures

Harsh, Unpredictable Community Environments

Primary caregivers completed the community environment instrument at baseline. It comprised items from multiple subscales adapted from the work of Sampson et al. (1997) measuring low neighborhood cohesion (4 items), low collective socialization (3 items), and social disorder (4 items). Low neighborhood cohesion addressed participants’ sense of trust, support, and connection with their neighbors (e.g., “About how often do you and people in your neighborhood do favors for each other?”; “When a neighbor is not at home, how often do you and other neighbors watch over their property?”). Responses ranged from 1 (often) to 3 (never). Low collective socialization was assessed with items such as, “If a group of neighborhood children were skipping school and hanging out on a street corner, how likely is it that your neighbors would do something like call the school or parents?” Responses ranged from 1 (very likely) to 4 (very unlikely). For social disorder, participants rated on a scale ranging from 1 (not at all a problem) to 3 (a big problem) how much of a problem “graffiti on buildings” and “gang violence” were for their neighborhood. Additional items about the safety of playgrounds and neighborhood streets for children were rated dichotomously (1 = true) or (2 = false). All items were standardized and summed to indicate a harsh, unpredictable community environment. Cronbach’s alpha for the measure was .75.

Harsh, Inconsistent, and Unregulated Parenting

At baseline, primary caregivers reported their parenting behaviors with a 14-item scale that included items addressing parental monitoring (4 items, e.g., “How often do you know when your child does something wrong?”), inductive parenting (6 items, e.g., “How often do you give reasons to your child for your decisions?”), and harsh/inconsistent discipline (4 items, e.g., “When you discipline your child, how often do you hit him with a belt, a paddle, or something else?”). Each item was assessed on a scale ranging from 1 (never) to 4 (always). The items were reverse coded if necessary so that higher scores indicated less regulated or predictable parenting and then summed. Cronbach’s alpha for the instrument was .71.

Negative Emotionality

Negative emotionality was assessed at baseline by youth self-report on a 4-item subscale from the Dimensions of Temperament Scale–Revised (Windle, 1992). The response set ranged from 1 (not at all true) to 3 (very true). An example item was, “You get upset easily.” Cronbach’s alpha for the scale was .73.

Body Mass Index

At baseline, youth reported their height and weight; with this information, Quetlet’s Index (Eknoyan, 2008) was used to calculate a body mass index (BMI) score for each youth.

Pubertal Development

Pubertal timing was assessed at baseline and at the second assessment using the Pubertal Development Scale (PDS) (Petersen, Crockett, Richards, & Boxer, 1988). On a scale ranging from 1 (have not begun) to 4 (development completed), boys indicated the extent to which they had experienced pubertal growth in several domains during the past 12 months. Items assessed body hair development, growth spurt, skin changes, and voice change. Alpha coefficient was .63 at baseline and .62 at age 13. Because youth’s ages varied somewhat at each assessment, we standardized the PDS scores within each year of age. This scoring procedure has been used previously (Ge, Brody, Conger, & Simons, 2006; Ge, Brody, Conger, Simons, & Murry, 2002). It generated a variable, pubertal timing, with a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1; higher scores indicated earlier maturation relative to peers of the same age.

Prior studies indicated that a small proportion of youth cannot reliably report pubertal status over time (Ge et al., 2003). We thus conducted additional data cleaning procedures. On the basis of procedures that Ge et al. described, we classified boys as prepubertal, early pubertal, midpubertal, late pubertal, or postpubertal at baseline and age 13 and identified those whose pubertal category “regressed” across 2 years. A total of 36 participants reported more advanced pubertal development at age 11 than at age 13. We then determined whether the regressors differed from nonregressors on any study variables; no significant differences emerged. Consistent with past research (Ge et al., 2003), we excluded the regressors from further analyses of study hypotheses. This resulted in a sample size of 375.

Sexual Risk Behavior

Sexual risk behavior was operationalized at age 16 as a latent construct with three indicators. Youth were asked “have you ever had sex with a girl?” The type of sexual activity in which they had engaged (e.g., vaginal, oral, anal) was not recorded. If they reported having had sex, they were also asked how old they were the first time they had sex. Based on their responses to these two questions, youth were assigned a 1 if they reported having sex before age 14 and a 0 if they did not report sexual activity prior to age 14. Sexually experienced youth answered two additional questions: “With how many people have you had sex?” with responses ranging from 1 (one) to 5 (7 or more), and “When you have sex, how often do you have some alcohol or drugs beforehand?” with responses ranging from 0 (never) to 3 (most of the time).

Analytic Plan

Hypotheses were tested with structural equation modeling as implemented in Mplus Version 7 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2012). Missing data were managed with Full Information Maximum Likelihood estimation. Prior to testing study hypotheses, we investigated the adequacy of the measurement model for the sexual risk behavior construct. Because age at onset of sexual activity and numbers of partners covary, we correlated the error terms between these indicators. We then specified direct effects from harsh, unpredictable community environments and harsh, inconsistent, or unregulated parenting at age 11 to pubertal status at age 13, controlling for pubertal status at age 11. We also specified parenting as a mediator of community effects on pubertal timing. Pubertal timing at age 13 was specified as a predictor of the latent sexual risk construct. The influence of baseline BMI on pubertal timing was controlled in all analyses. Moderational hypotheses were tested with multigroup structural equation models comparing paths for high and low negative emotionality groups formed via median split.

Results

Preliminary Analyses and Descriptive Statistics

The measurement model fit the data as follows: χ2 = 2.82, df = 9, p = .97; RMSEA = .00; CFI = 1.00. The factor loadings on the latent variable were significant (p < .001), exceeded .44, and were in the expected directions. Table 1 shows the study variables’ intercorrelations, means, and SDs. The average PDS total score for this sample of African American boys at age 11 was 1.84 (SD = 0.52), suggesting that their pubertal development had just begun. Their average PDS total score increased to 2.26 (SD = 0.51) two years later, indicating that they were well into puberty. Overall, the pubertal development levels among the youth in the present sample were consistent with normative ranges for youth at these ages (Herman-Giddens, 2006). At age 16, 40.3 % of the sample reported never having sexual intercourse, 13.1 % reported one partner, 12.5 % reported two partners, and the remaining 34.2 % reported three or more partners. Approximately 30 % of the sample reported having sexual intercourse prior to the age of 14, and 10 % of sexually active youth reported using substances prior to sexual activity.

Test of Study Hypotheses

Figure 2 shows the direct and indirect effects model predicting sexual risk behavior. The model fit the data as follows: χ2 = 12.77, df = 14, p = .54; RMSEA = .01; CFI = .99. For the whole sample, parenting did not predict pubertal status; community disadvantage, however, exhibited a significant (p < .05), though modest effect (β = .11). Consistent with expectations, pubertal status at age 13 was associated significantly with involvement in sexual risk behavior at age 16 (β = .21, p < .05).

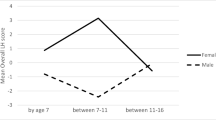

Figure 3 shows the results of the multigroup analyses comparing coefficients based on high or low negative emotionality. Negative emotionality moderated the paths from community environment (∆χ 2[1] = 8.54, p < .01) and parenting (∆χ 2[1] = 9.58, p < .01) to pubertal status. For youth with high negative emotionality, community disadvantage (β = .28, p < .01) and harsh, inconsistent, or unregulated parenting (β = .25, p < .01) predicted pubertal status at age 13. We used bootstrapping to test the indirect effects of community disadvantage and parenting on sexual risk behavior via pubertal status. No significant indirect effects emerged.

Discussion

We tested hypotheses, informed by LHT and environmental susceptibility perspectives, regarding the influence of community disadvantage and parenting practices on pubertal timing and sexual risk behavior among a sample of African American male youth. Past findings suggested that male youth’s pubertal timing was not influenced by aspects of their social environment. The majority of these studies, however, did not investigate community stressors or consider the susceptibility to stress conferred by temperament dimensions such as negative emotionality. We hypothesized that community environments would predict youth’s pubertal timing, and that both community stressors and parenting practices would be particularly strong predictors for youth who evinced high negative emotionality.

Findings were consistent with our hypotheses. In our first model, we found that, for the entire sample, harsh, unpredictable community environments were associated with early pubertal maturation. The analyses focused on negative emotionality as a moderator revealed that, for youth high in negative emotionality, both parenting and community processes were robust predictors of pubertal timing. In contrast, among those youth who reported low levels of negative emotionality, family and community environments had no significant influence on pubertal timing. Also consistent with expectations, youth who reported higher levels of pubertal development at age 13 were more likely to engage in sexual risk behaviors at age 16, including onset of sexual activity prior to age 14, multiple sexual partners, and substance use during sexual activity.

These results inform a developing literature that suggests that evolutionary mechanisms designed to accelerate or conserve growth and reproduction based on environmental circumstances affected human development. Accumulating evidence confirms the influence of contextual stressors, particularly those in family environments, on adolescent girls’ pubertal timing. Stressful, chaotic family environments as well as the presence of a stepfather have been linked to early menarche and subsequent risk for precocious sexual activity and pregnancy (Mendle & Ferrero, 2012). Belsky, Steinberg, and Draper (1991) hypothesized that male youth who grew up in challenging environments would evince short-term reproductive strategies. Given uncertainty in the environment, delaying procreation to accumulate resources to attract mates or to invest in the well-being of future children may have resulted in lowered reproductive fitness. Timing of pubertal maturation was hypothesized to be a key somatic link representing variability in LH pacing. Our results suggest, particularly for environmentally sensitive youth as indicated by negative emotionality, that LHT predictions were informative and that male youth’s pubertal timing was responsive to contextual influences.

An important contribution of the present study involved the assessment of neighborhood influences. Studies of the psychosocial precursors of pubertal maturation have focused primarily on stressful or harmonious family environments. Several suggested that experiences in the community were particularly relevant to male youth’s developmental outcomes (Kogan et al., 2010; Ramirez-Valles et al., 2002; Simons, Johnson, Beaman, Conger, & Whitbeck, 1996). Although family processes remained important predictors of males’ development, additional attention in policy and prevention efforts should be directed to the influence of communities on male youth’s developmental outcomes. Male youth’s sensitivity to community effects was underscored in the present study by the significant main effect on pubertal timing as well as the robust influence of community factors on the subsample high in negative emotionality. Also consistent with previous studies, community environments affected youth’s development directly, as well as indirectly by undermining effective parenting.

Study results supported the notion that youth vary in the extent to which environmental factors affect their development. Belsky and Pluess (2009) theorized that, because the future is uncertain, in ancestral times parents could not know for certain (consciously or unconsciously) what rearing strategies would maximize reproductive fitness. For example, parents may have encouraged a long-term reproductive strategy when the environment might have favored a short-term one. To protect against all children being steered, inadvertently, in a direction that could prove disastrous at some later point in time, developmental processes were selected to vary children’s susceptibility to rearing influences. Our results extended this contention to aspects of the community environment and to a somatic, developmental outcome, pubertal maturation. For male youth who were low in negative emotionality, parenting behavior had little or no effect on pubertal timing and community stressors had modest effects. In contrast, those high in negative emotionality who experienced stressful parenting and community experiences evinced the early pubertal maturation that accompanies a “fast” life history strategy. This finding was consistent with a prior study (Ellis et al., 2011) that found that susceptibility to environmental stressors, as measured by cortisol production, predicted early puberty for both male and female youth.

Consistent with our hypotheses, male youth who matured early also evinced more sexual risk behavior. Indirect effect analyses, however, did not find that pubertal maturation mediated contextual influences on sexual risk behavior. We speculated that this finding may have pointed to differences in the current and the ancestral environments in which humans evolved. Our results supported the LHT contention that humans evolved the capacity to accelerate pubertal maturation in response to contextual factors. It may have been that, in the ancestral environment, early puberty was a particularly robust factor predicting sexual behavior. We speculated that, in the current environment, physical maturation is one of many important factors such as peer affiliations and school environment that predict sexual behavior in adolescence.

Strengths of the present study included the use of longitudinal data spanning ages 11–16 and a multi-informant measurement strategy. Despite these strengths, limitations of the study must be noted. Pubertal maturation was assessed via self-report and would benefit from supplementation by medical examination. Sample size was modest, so main effects on puberty may have emerged with a larger sample. BMI was calculated using self-reported data rather than anthropometric methods, which provide more reliable assessments. Important alternative mechanisms in community and family environments remain to be investigated. For example, community environments may influence the availability of potential sexual partners. Patterns of sexual partnering in which age differences are considered may also illuminate LHT-relevant mechanisms. Finally, the use of a racially homogenous sample revealed important within-group differences; however, additional research is needed to determine whether the findings generalize to male adolescents of other races/ethnicities. Furthermore, race is a predictor of early pubertal development processes. Thus, further examination of the study hypotheses in multiethnic samples is warranted. These cautions notwithstanding, the results of the present study identified key processes that affected male adolescents’ pubertal maturation and contributed to the identification of developmental mechanisms that predicted sexual behavior in adolescence.

References

Baker, J. G., Rosenthal, S. L., Leonhardt, D., Kollar, L. M., Succop, P. A., Burklow, K. A., & Biro, F. M. (1999). Relationship between perceived parental monitoring and young adolescent girls’ sexual and substance use behaviors. Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology, 12, 17–22. doi:10.1016/S1083-3188(00)86615-2.

Bates, J. E., Pettit, G. S., Dodge, K. A., & Ridge, B. (1998). Interaction of temperamental resistance to control and restrictive parenting in the development of externalizing behavior. Developmental Psychology, 34, 982–995. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.34.5.982.

Belsky, J. (2010). Childhood experience and the development of reproductive strategies. Psicothema, 22, 28–34.

Belsky, J., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., & van IJzendoorn, M. H. (2007). For better and for worse: Differential susceptibility to environmental influences. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 16, 300–304. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8721.2007.00525.x.

Belsky, J., & Pluess, M. (2009). Beyond diathesis stress: Differential susceptibility to environmental influences. Psychological Bulletin, 135, 885–908. doi:10.1037/a0017376.

Belsky, J., Schlomer, G. L., & Ellis, B. J. (2012). Beyond cumulative risk: Distinguishing harshness and unpredictability as determinants of parenting and early life history strategy. Developmental Psychology, 48, 662–673. doi:10.1037/a0024454.

Belsky, J., Steinberg, L., & Draper, P. (1991). Childhood experience, interpersonal development, and reproductive strategy: An evolutionary theory of socialization. Child Development, 62, 647–670. doi:10.2307/1131166.

Belsky, J., Steinberg, L.D., Houts, R.M., Friedman, S.L., DeHart, G., Cauffman, E., … The NICHD Early Child Care Research Network. (2007b). Family rearing antecedents of pubertal timing. Child Development, 78, 1302–1321. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01067.x.

Bogaert, A. F. (2005). Age at puberty and father absence in a national probability sample. Journal of Adolescence, 28, 541–546. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2004.10.008.

Brewster, K. L. (1994). Neighborhood context and the transition to sexual activity among young Black women. Demography, 31, 603–614.

Brody, G. H., Ge, X., Conger, R., Gibbons, F. X., Murry, V. M., Gerrard, M., & Simons, R. L. (2001). The influence of neighborhood disadvantage, collective socialization, and parenting on African American children’s affiliation with deviant peers. Child Development, 72, 1231–1246. doi:10.1111/1467-8624.00344.

Compas, B. E., Connor-Smith, J., & Jaser, S. S. (2004). Temperament, stress reactivity, and coping: Implications for depression in childhood and adolescence. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 33, 21–31. doi:10.1207/S15374424JCCP3301_3.

De Genna, N. M., Larkby, C., & Cornelius, M. D. (2011). Pubertal timing and early sexual intercourse in the offspring of teenage mothers. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 40, 1315–1328. doi:10.1007/s10964-010-9609-3.

Del Giudice, M., & Belsky, J. (2010). Evolving attachment theory: Beyond Bowlby and back to Darwin. Child Development Perspectives, 4, 112–113. doi:10.1111/j.1750-8606.2010.00128.x.

Eaton, D.K., Kann, L., Kinchen, S., Shanklin, S., Flint, K.H., Hawkins, J., … Wechsler, H. (2012). Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States, 2011. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report: Surveillance Summaries, 61(4), 1–162.

Eknoyan, G. (2008). Adolphe Quetelet (1796–1874)—the average man and indices of obesity. Nephrology, Dialysis, Transplantation, 23, 47–51. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfm517.

Ellis, B. J. (2004). Timing of pubertal maturation in girls: An integrated life history approach. Psychological Bulletin, 130, 920–958. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.130.6.920.

Ellis, B. J. (2005). Determinants of pubertal timing: An evolutionary developmental approach. In B. J. Ellis & D. F. Bjorklund (Eds.), Origins of the social mind: Evolutionary psychology and child development (pp. 164–188). New York: Guilford Press.

Ellis, B.J., Del Giudice, M., Dishion, T.J., Figueredo, A.J., Gray, P., Griskevicius, V., … Wilson, D.S. (2012). The evolutionary basis of risky adolescent behavior: Implications for science, policy, and practice. Developmental Psychology, 48, 598–623. doi:10.1037/a0026220.

Ellis, B. J., & Essex, M. J. (2007). Family environments, adrenarche, and sexual maturation: A longitudinal test of a life history model. Child Development, 78, 1799–1817. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01092.x.

Ellis, B. J., Shirtcliff, E. A., Boyce, W. T., Deardorff, J., & Essex, M. J. (2011). Quality of early family relationships and the timing and tempo of puberty: Effects depend on biological sensitivity to context. Development and Psychopathology, 23, 85–99. doi:10.1017/s0954579410000660.

Ge, X., Brody, G. H., Conger, R. D., & Simons, R. L. (2006). Pubertal maturation and African American children’s internalizing and externalizing symptoms. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 35, 528–537. doi:10.1007/s10964-006-9046-5.

Ge, X., Brody, G. H., Conger, R. D., Simons, R. L., & Murry, V. M. (2002). Contextual amplification of pubertal transition effects on deviant peer affiliation and externalizing behavior among African American children. Developmental Psychology, 38, 42–54. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.38.1.42.

Ge, X., Kim, I. J., Brody, G. H., Conger, R. D., Simons, R. L., Gibbons, F. X., & Cutrona, C. E. (2003). It’s about timing and change: Pubertal transition effects on symptoms of major depression among African American youths. Developmental Psychology, 39, 430–439. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.39.3.430.

Gibbons, F. X., Gerrard, M., Cleveland, M. J., Wills, T. A., & Brody, G. H. (2004). Perceived discrimination and substance use in African American parents and their children: A panel study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 86, 517–529. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.86.4.517.

Henrich, C. C., Brookmeyer, K. A., Shrier, L. A., & Shahar, G. (2006). Supportive relationships and sexual risk behavior in adolescence: An ecological–transactional approach. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 31, 286–297. doi:10.1093/jpepsy/jsj024.

Herman-Giddens, M. E. (2006). Recent data on pubertal milestones in United States children: The secular trend toward earlier development. International Journal of Andrology, 29, 241–246. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2605.2005.00575.x.

James, J., Ellis, B. J., Schlomer, G. L., & Garber, J. (2012). Sex-specific pathways to early puberty, sexual debut, and sexual risk taking: Tests of an integrated evolutionary developmental model. Developmental Psychology, 48, 687–702. doi:10.1037/a0026427.

Kogan, S. M., Brody, G. H., Chen, Y.-f., Grange, C. M., Slater, L. M., & DiClemente, R. J. (2010). Risk and protective factors for unprotected intercourse among rural African American young adults. Public Health Reports, 125, 709–717.

Kogan, S.M., Brody, G.H., Gibbons, F.X., Chen, Y.-f., Grange, C., Simons, R.L., … Cutrona, C.E. (2011). Mechanisms of family impact on African American adolescents’ HIV-related behavior. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 21, 361–375. doi:10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00672.x.

Koniak-Griffin, D., Lesser, J., Uman, G., & Nyamathi, A. (2003). Teen pregnancy, motherhood, and unprotected sexual activity. Research in Nursing & Health, 26, 4–19. doi:10.1002/nur.10062.

Kruger, D. J., Reischl, T., & Zimmerman, M. A. (2008). Time perspective as a mechanism for functional developmental adaptation. Journal of Social, Evolutionary, and Cultural Psychology, 2, 1–22. doi:10.1037/h0099336.

Lee, J., Kaciroti, N., Appugliese, D., Corwyn, R. F., Bradley, R. H., & Lumeng, J. C. (2010). Body mass index and timing of pubertal initiation in boys. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 164, 139–144. doi:10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.258.

Mendle, J., & Ferrero, J. (2012). Detrimental psychological outcomes associated with pubertal timing in adolescent boys. Developmental Review, 32, 49–66. doi:10.1016/j.dr.2011.11.001.

Miller, B. C. (2002). Family influences on adolescent sexual and contraceptive behavior. Journal of Sex Research, 39, 22–26. doi:10.1080/00224490209552115.

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998–2012). Mplus user’s guide (7th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén.

Natsuaki, M. N., Ge, X., Brody, G. H., Simons, R. L., Gibbons, F. X., & Cutrona, C. E. (2007). African American children’s depressive symptoms: The prospective effects of neighborhood disorder, stressful life events, and parenting. American Journal of Community Psychology, 39, 163–176. doi:10.1007/s10464-007-9092-5.

Neberich, W., Penke, L., Lehnart, J., & Asendorpf, J. B. (2010). Family of origin, age at menarche, and reproductive strategies: A test of four evolutionary-developmental models. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 7, 153–177. doi:10.1080/17405620801928029.

Negriff, S., Susman, E. J., & Trickett, P. K. (2011). The developmental pathway from pubertal timing to delinquency and sexual activity from early to late adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 40, 1343–1356. doi:10.1007/s10964-010-9621-7.

Petersen, A., Crockett, L., Richards, M., & Boxer, A. (1988). A self-report measure of pubertal status: Reliability, validity, and initial norms. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 17, 117–133. doi:10.1007/bf01537962.

Pinderhughes, E. E., Nix, R., Foster, E. M., & Jones, D. (2001). Parenting in context: Impact of neighborhood poverty, residential stability, public services, social networks, and danger on parental behaviors. Journal of Marriage and Family, 63, 941–953. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2001.00941.x.

Quinlan, R. J. (2003). Father absence, parental care, and female reproductive development. Evolution and Human Behavior, 24, 376–390. doi:10.1016/s1090-5138(03)00039-4.

Ramirez-Valles, J., Zimmerman, M. A., & Juarez, L. (2002). Gender differences of neighborhood and social control processes: A study of the timing of first intercourse among low-achieving, urban, African American youth. Youth & Society, 33, 418–441. doi:10.1177/0044118X02033003004.

Repetti, R. L., Taylor, S. E., & Seeman, T. E. (2002). Risky families: Family social environments and the mental and physical health of offspring. Psychological Bulletin, 128, 330–366. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.128.2.330.

Sampson, R. J., Raudenbush, S. W., & Earls, F. (1997). Neighborhoods and violent crime: A multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science, 277, 918–924. doi:10.1126/science.277.5328.918.

Savolainen, J., Mason, W. A., Hughes, L. A., Ebeling, H., Hurtig, T. M., & Taanila, A. M. (2012). Pubertal development and sexual intercourse among adolescent girls: An examination of direct, mediated, and spurious pathways. Youth & Society. doi:10.1177/0044118x12471355.

Simons, R. L., Johnson, C., Beaman, J., Conger, R., & Whitbeck, L. (1996). Parents and peer group as mediators of the effect of community structure on adolescent problem behavior. American Journal of Community Psychology, 24, 145–171. doi:10.1007/bf02511885.

Simons, R. L., Lin, K., Gordon, L. C., Brody, G. H., & Conger, R. D. (2002a). Community differences in the association between parenting practices and child conduct problems. Journal of Marriage and Family, 64, 331–345. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2002.00331.x.

Simons, R. L., Murry, V. M., McLoyd, V., Lin, K.-H., Cutrona, C., & Conger, R. D. (2002b). Discrimination, crime, ethnic identity, and parenting as correlates of depressive symptoms among African American children: A multilevel analysis. Development and Psychopathology, 14, 371–393. doi:10.1017/S0954579402002109.

Simons, R. L., Simons, L. G., Chen, Y.-f., Brody, G. H., & Lin, K.-H. (2007). Identifying the psychological factors that mediate the association between parenting practices and delinquency. Criminology, 45, 481–517. doi:10.1111/j.1745-9125.2007.00086.x.

Stearns, S. C., Allal, N., & Mace, R. (2008). Life history theory and human development. In C. Crawford & D. Krebs (Eds.), Foundations of evolutionary psychology (pp. 47–70). New York: Erlbaum.

Upchurch, D. M., Aneshensel, C. S., Sucoff, C. A., & Levy-Storms, L. (1999). Neighborhood and family contexts of adolescent sexual activity. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 61, 920–933. doi:10.2307/354013.

Walton, A., & Flouri, E. (2010). Contextual risk, maternal parenting and adolescent externalizing behaviour problems: The role of emotion regulation. Child: Care. Health and Development, 36, 275–284. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2214.2009.01065.x.

Wills, T. A., Sandy, J. M., Yaeger, A. M., & Shinar, O. (2001). Family risk factors and adolescent substance use: Moderation effects for temperament dimensions. Developmental Psychology, 37, 283–297. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.37.3.283.

Windle, M. (1992). A longitudinal study of stress buffering for adolescent problem behaviors. Developmental Psychology, 28, 522–530. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.28.3.522.

Acknowledgments

The research described in this article was funded by grant number R01 MH062669 from the National Institute of Mental Health to Ronald L. Simons, Grant number R01 DA021898 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse to Frederick X. Gibbons, and Grant number P30 DA027827 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse to Gene H. Brody.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kogan, S.M., Cho, J., Simons, L.G. et al. Pubertal Timing and Sexual Risk Behaviors Among Rural African American Male Youth: Testing a Model Based on Life History Theory. Arch Sex Behav 44, 609–618 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-014-0410-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-014-0410-3