Abstract

The purpose of this study was to determine if self-identified bisexual, heterosexual, and homosexual men show differential genital and subjective arousal patterns to video presentations of bisexual, heterosexual, male homosexual, and lesbian sexual interactions. It was predicted that, relative to heterosexual and homosexual stimuli, bisexual men would show the highest levels of sexual arousal to bisexual erotic material, while this stimulus would induce relatively low levels of response in heterosexual and homosexual men. A sample of 59 men (19 homosexual, 13 bisexual, and 27 heterosexual) were presented with a series of 4-min sexual videos while their genital and subjective sexual responses were measured continuously. Bisexual men did not differ significantly in their responses to male homosexual stimuli (depicting men engaging in sex) from homosexual men, and they did not differ significantly in their responses to heterosexual (depicting two women, without same-sex contact, engaged in sex with a man) and lesbian (depicting women engaging in sex) stimuli from heterosexual men. However, bisexual men displayed significantly higher levels of both genital and subjective sexual arousal to a bisexual stimulus (depicting a man engaged in sex with both a man and a woman) than either homosexual or heterosexual men. The findings of this study indicate that bisexuality in men is associated with a unique and specific pattern of sexual arousal.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The findings of several large-scale interview and questionnaire studies (Kinsey, Pomeroy, & Martin, 1948; Kinsey, Pomeroy, Martin, & Gebhard, 1953; Laumann, Gagnon, Michael, & Michaels, 1994; Weinberg, Williams, & Pryor, 1994) seem to provide unequivocal support for the existence of a bisexual sexual orientation, especially when sexual orientation is assessed in terms of fantasies, attraction, and behavior. In contrast, psychophysiological studies, examining the association between sexual orientation and sexual arousal, provide a more mixed picture and have left the construct of bisexuality, especially when applied to men, in uncertain, if not controversial, waters. For example, McConaghy and Blaszczynski (1991) found a significant correlation between changes in penile volume in response to male and female nudes and questionnaire ratings of sexual attraction to men and women. These researchers reported that bisexual participants showed bisexual arousal and concluded that their findings indicate “that the balance of heterosexual/homosexual feeling is dimensionally distributed” (p. 57). However, this study involved a small sample and the participants were sex offenders or men seeking treatment for compulsive sexual behaviors. Tollison, Adams, and Tollison (1979), in a study comparing groups of self-identified heterosexual, homosexual, and bisexual men, found differences between these groups in subjective ratings of sexual arousal and estimates of erections in response to heterosexual (depicting a man and woman engaging in sex) and homosexual (depicting two men engaging in sex) films and slides of nude men and women. But since erectile responses of the bisexual and homosexual groups were indistinguishable, the researchers concluded that “in terms of physiological arousal, these results question the existence of male bisexuality as distinct from homosexuality or as a separate sexual orientation in males” (p. 311).

More recently, Rieger, Chivers, and Bailey (2005) grouped men on the basis of attraction scores on the Kinsey et al. (1948) scale and analyzed within-subject standardized scores of genital and subjective arousal to 2-min film clips that depicted either two men or two women having sex with each other. They found that men who reported bisexual feelings did not present evidence of a distinctively bisexual pattern of genital arousal (e.g., by responding similarly to “male” and “female” sexual stimuli). That is, bisexual men, similar to homosexual and heterosexual men, had stronger genital responses to films of one kind than the other. When it comes to self-reported sexual arousal, however, Rieger et al. did find a distinctive pattern of bisexual arousal in the bisexual men. They suggested that, since the correlation between subjective and genital arousal in males was generally high (cf. Chivers, Seto, Lalumiere, Laan, & Grimbos, 2010), the bisexual men either exaggerated their subjective arousal ratings or suppressed their genital arousal to the less preferred sexual stimuli. Citing Tollison et al. (1979), Rieger et al. proposed that, more than likely, the bisexual men in their study tended to exaggerate subjective levels of sexual arousal to less preferred stimuli and concluded that it remains to be shown that, with respect to sexual arousal and attraction, male bisexuality exists.

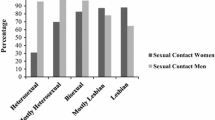

In the above studies, groups of heterosexual, bisexual, and homosexual men were shown relatively brief erotic stimuli depicting heterosexual or male homosexual behavior. Previous research has shown that heterosexual men reach highest levels of arousal while viewing heterosexual or lesbian erotica (women engaging in sexual activity together), while homosexual men reach highest arousal when watching homosexual erotica (men engaging in sex together; Mavissakalian, Blanchard, Abel, & Barlow, 1975; McConaghy & Blaszczynski, 1991; Sakheim, Barlow, Beck, & Abrahamson, 1985; Tollison et al., 1979). Homosexual men show minimal arousal to heterosexual or lesbian erotica, and heterosexual men show minimal arousal to male homosexual erotica. It has been proposed that bisexual men should show similar levels of arousal to homosexual and heterosexual erotica or, alternatively, higher levels of arousal to homosexual stimuli than heterosexual men and higher levels of arousal to heterosexual stimuli than homosexual men (cf. Rieger et al., 2005). From this perspective, bisexual men should show arousal patterns similar to homosexual men when looking at two men having sex and to heterosexual men when viewing a man and a woman or two women having sex. Although the assumption that bisexuality should be associated with similar levels of sexual arousal to “male” and “female” stimuli is defendable (although not necessarily consistent with the wide range of Kinsey scores used by some researchers to classify participants as bisexual; e.g., Rieger et al., 2005), it does not address the possibility that a bisexual orientation is associated with responsivity to certain specific stimuli that would induce relatively low levels of sexual arousal in heterosexual and homosexual individuals.

Previous research has shown that the type (e.g., visual, auditory, other modalities; Abel, Barlow, Blanchard, & Mavissakalian, 1975; Abel, Blanchard, & Barlow, 1981; Julien & Over, 1988; McConaghy, 1974; Sakheim et al., 1985; Tollison et al., 1979), characteristics (e.g., duration, color versus black and white, soundtrack included or not; Gaither & Plaud, 1997; High, Rubin, & Henson, 1979; Youn, 2006), content (e.g., the specific behaviors depicted; Abel et al., 1981; Chivers, Seto, & Blanchard, 2007; Hatfield, Sprecher, & Traupmann, 1978; Janssen, Carpenter, & Graham, 2003; Mosher & Abramson, 1977; Wright & Adams, 1994, 1999), and emotional/cognitive variables (e.g., Cranston-Cuebas & Barlow, 1990; Janssen & Everaerd, 1993; Nobre et al., 2004; Peterson & Janssen, 2007) associated with stimuli used to elicit sexual arousal responses in the laboratory are all important and influential variables. The general consensus seems to be that moving images (film or video) with sound that facilitate positive emotion and thoughts lead to the highest levels of sexual arousal. However, there have been no studies identifying which stimulus dimensions, including the behavior or configuration of actors involved, lead to adequate or discriminating levels of sexual arousal in a laboratory setting for men with bisexual histories or preferences. In fact, none of the existing studies that have attempted to differentiate sexual arousal patterns among groups of bisexual, homosexual, and heterosexual men have included a sexual stimulus that might, in content, be considered “bisexual” (e.g., by showing a man having sex with another man and with a woman).

The purpose of the current study was to determine if self-identified bisexual, heterosexual, and homosexual men show differential genital and subjective arousal patterns to video presentations of heterosexual (two women, without same-sex contact, engaging in sex with a man), homosexual (three men engaging in sex), lesbian (two women engaging in sex), and bisexual (two men engaging in sex with one another and with a woman) sexual behaviors. We predicted that bisexual men would show higher levels of sexual arousal to bisexual erotic material than to other types of erotic stimuli, and that a bisexual stimulus would induce relatively low levels of response in heterosexual and homosexual men.

Method

Participants

Participants were recruited through announcements in local community and campus newspapers at a medium-sized midwestern university. The announcements invited men of all sexual orientations to participate in a study on male sexual arousal. A pre-experimental session, which took place 1–2 weeks before the laboratory session, was scheduled and used to collect demographic information as well as data about sexual attitudes, sexual behavior, sexual relationships, and sexual orientation. Participants were at least 18 years of age, reported no history of psychiatric diagnoses or treatment and no current sexual dysfunctions, and were paid $20.00 for their participation in the study. Study approval was obtained from the university’s Human Subjects Committee.

A total of 65 men completed the study, but data from six men were excluded from analyses for the following reasons: Three participants (two homosexual, one bisexual) were non-responders (i.e., responses of less than 5 mm to all sexual stimuli), one heterosexual participant self-stimulated during a video, one homosexual participant revealed during the debriefing interview that he was using a psychotropic medication, and one heterosexual participant’s data were excluded because of experimenter error. Therefore the final sample of 59 participants consisted of 27 heterosexual men, 19 homosexual men, and 13 bisexual men.

Procedure and Measures

Stimuli

Participants were presented with four 4-min excerpts from commercially available erotic videos, and a nonsexual travelogue of a national park. Each erotic video depicted actors engaged in fondling, oral–genital sex, and manual genital stimulation and/or intercourse. One of the erotic video clips showed two women, without same-sex contact, engaged in sexual activity with a man, depicting fellatio and vaginal intercourse. As this video clip did not involve any same-sex sexual activity, we will refer to this clip as the “heterosexual stimulus.” A second video clip (the “homosexual stimulus”) showed three men having sex, depicting fellatio and anal intercourse. A third clip (the “lesbian stimulus”) showed two women engaged in sex with one another, depicting petting, cunnilingus, and manual stimulation. A fourth video clip showed two men and a woman. This video depicted a woman and man fondling each other while both fellating another man, vaginal intercourse combined with digital anal stimulation of the second man, and male–male anal intercourse. As this video showed both male–male and male–female sexual behavior, involving the same actors, this video will be referred to as the “bisexual stimulus.”

Self-Report Measures

Sexual Orientation

Information on sexual orientation was gathered in three ways: (1) During the pre-experimental session, each man was interviewed and asked to rate himself on the Kinsey scale (0–6; Kinsey et al., 1948) twice, once in terms of sexual behavior and once in terms of sexual attraction; (2) they were asked to self-identify, in the present time, as heterosexual, homosexual, or bisexual; and (3) at the beginning of the experimental session, each participant was asked to once more identify himself as heterosexual, bisexual, or homosexual and to indicate his preference for sexual partner (male, female, both male and female). Although group assignment was based on self-identification, we examined the correlations between self-identification and the two Kinsey ratings, which were high for both behavioral (r = .94) and attraction (r = .93) ratings.

Other Trait Measures

Participants also completed the Sensation Seeking Scale (Zuckerman, Kolin, Price, & Zoob, 1964) and the Sex Guilt scale from the Mosher Sex Guilt Inventory (Abramson & Mosher, 1975). Scores for the Sensation Seeking Scale range from 0 to 40. Sex Guilt scores range from −45 to +37. Previous research (e.g., Mosher, 1966) has found this scale to be related to a range of sexual attitudes and behaviors.

Subjective Arousal and Affect

Subjective sexual arousal was measured by asking participants to move a lever continuously during the stimulus presentations to indicate their feelings of sexual arousal. The lever could be moved in a 180-degree arc that was calibrated on a scale from 0 to 100% sexually aroused. In addition, after each video presentation, participants were asked to rate the stimulus on a 0 (Not at all) to 8 (High) scale for sexual arousal, disgust, exciting, obscene, aggressive, enjoyable, hostile, offensive, and threatening.

Genital Response

Genital responses were measured using a mercury-in-rubber penile gauge (Bancroft, Jones, & Pullan, 1966). The penile gauges, which assess penile circumference, were calibrated at the start and end of each laboratory session using a set of calibrated metal rings (cf. Janssen, Prause, & Geer, 2007). Participants were instructed to place the gauge midway along the penile shaft. Psychophysiological data were recorded on a Grass (model B) 8-channel physiograph and were hand-scored by research assistants under the supervision of the authors. Scorers were masked to the participants’ self-reported sexual orientation.Footnote 1

Men who met inclusion criteria were given a tour of the laboratory to help them become familiarized with the apparatus and procedures used in the study. Men who decided to volunteer for the study signed an informed consent form and completed a set of paper and pencil questionnaires. After completing the questionnaires, the participant was scheduled for the experimental session. During the experimental session, the procedures and study instructions were once again described to the participants. After the experimenter left the chamber, the participant placed the gauge on his penis and sat in a comfortable, padded chair. The participant then informed the experimenter, using an intercom, that he was ready to continue. The experimenter re-entered the experimental chamber, visually verified proper gauge placement, repeated the appropriate experimental instructions, asked if the participant had any questions, and then returned to the control room. After a 2-min baseline had been collected, the first of five (four erotic and one neutral) videos was presented, after which the participant completed the rating scales and was asked to relax in order to allow their genital response to return to baseline. Those participants who had difficulty returning to within 5 mm of their initial baseline were asked to count backwards by threes from 1000 until returning to original baseline levels for at least 1 min, after which the next video was presented. The five videos were presented in random order. At completion of the experimental session, the participant completed a post-experimental questionnaire and a debriefing interview.

Data Analysis

Genital responses and continuous subjective arousal were calculated using the mean difference between responses to sexual stimuli minus responses to the neutral stimulus at a minute-by-minute basis. Analyses were conducted using a 3 (Group) × 4 (Erotic Stimulus) × 4 (Time) mixed-model factorial design. Group was a between-subjects factor with three levels, based on the participants’ self-identified orientation (Heterosexual, Bisexual, and Homosexual). For the two within-subjects variables, Erotic Stimulus and Time, each minute of the 4-min visual stimulus trial was nested within each type of stimulus (heterosexual, bisexual, lesbian, and homosexual). SPSS 14 for Windows and SPSS 11 for Mac OS X were used for all analyses. The Greenhouse-Geisser epsilon procedure was applied to mixed-factor ANOVAs to correct for the violation of the sphericity assumption in repeated measures designs (Vasey & Thayer, 1987). Effect sizes were estimated with partial eta squared (η 2p ). Simple effects were tested using Sidak’s adjustment for family-wise error.

Results

Sample Characteristics

Of the 59 men included in the data analysis, 55 (93%) had never been married, three of the heterosexual men were married, and one of the bisexual men was divorced. Participants were primarily Caucasian, with three African-Americans, one Asian-American, two Hispanics, and one Native American. Ten men were Catholic, 33 Protestant, two held other religious beliefs, and 14 reported no religious affiliation. Other demographic and sexual history variables are presented in Table 1.

Genital Responses

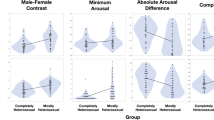

A 3 (Group: Homosexual, Bisexual, Heterosexual) × 4 (Erotic Stimulus: Homosexual, Bisexual, Heterosexual, Lesbian) × 4 (Time) mixed-model ANOVA was performed on the genital response data. As can be seen in Table 2, there were significant main effects for Erotic Stimulus and Time, a significant Group × Erotic Stimulus interaction, and a significant Group × Erotic Stimulus × Time interaction. Figure 1 shows the genital responses for the three groups across the 4-min trials for each type of erotic stimulus.

Follow-up tests for the individual stimuli revealed no significant main or interaction effects for the heterosexual video. For the homosexual stimulus, both the effect of Group, F(2, 56) = 18.34, p < .001, and of Group × Time, F(6, 168) = 9.50, p < .001, were significant. Post-hoc contrasts revealed no significant differences between the homosexual and bisexual men for any of the 4 min, but the heterosexual men displayed significantly lower levels of penile erection than either the bisexual or homosexual group for minutes 2–4, t(56) = 3.18–4.85, ps < .002. For the bisexual stimulus, only the main effect of Group was significant, F(2, 56) = 3.19, p < .05. Bisexual men had significantly stronger genital responses to the bisexual film than both the homosexual men, F(1, 30) = 5.18, p < .03, and the heterosexual men, F(1, 38) = 5.07, p < .03. The heterosexual and homosexual men did not differ in their response to the bisexual film. For the lesbian stimulus, the effects of Group, F(2, 56) = 11.73, p < .001, and Group × Time, F(6, 168) = 3.38, p < .02, were both significant. Post-hoc contrasts revealed that the heterosexual men responded with significantly larger increases in penile tumescence to the lesbian film stimulus than the homosexual men during all 4 min, t(56) = 2.68–4.06, ps < .01, of the video and the bisexual men during the first minute, t(56) = 2.49, p < .02, of the video. Differences between the bisexual and homosexual men were not significant.Footnote 2

Subjective Sexual Arousal

A 3 (Group: Homosexual, Bisexual, Heterosexual) × 4 (Erotic Stimulus: Homosexual, Bisexual, Heterosexual, Lesbian) × 4 (Time) mixed-model ANOVA for the subjective arousal lever data revealed significant main effects of Erotic Stimulus and Time (see Table 3). In addition, there was a significant Group × Erotic Stimulus × Time interaction, F(18, 504) = 13.58, p < .001 (see Fig. 2).Footnote 3

Follow-up tests for the individual videos revealed that the three groups did not differ significantly in their subjective responses to the heterosexual stimulus, Group: F(2, 56) = 2.17, ns; Group × Time: F(6, 168) < 1. For the homosexual stimulus, both the effect of Group, F(2, 56) = 35.38, p < .001, and of Group × Minute, F(6, 168) = 19.15, p < .001, were significant. Post-hoc contrasts revealed a significant difference, but only for the fourth minute, between the homosexual and bisexual men, t(56) = 2.33, p < .03. The heterosexual men reported significantly lower levels of sexual arousal than either the bisexual or homosexual group for all 4 min, t(56) = 3.02–9.18, ps < .002. For the bisexual film stimulus, the main effect of Group was not significant, but the interaction between Group × Minute was, F(6, 168) = 4.36, p < .001. Post-hoc contrasts showed that the three groups did not differ in subjective sexual arousal during the first 3 min. However, during the fourth minute, the bisexual, t(56) = 3.02, p < .005, and the homosexual, t(56) = 3.01, p < .005, groups, while not differing from each other, reported significantly stronger subjective sexual arousal than the heterosexual men. Finally, for the lesbian stimulus, the effects of Group, F(2, 56) = 17.78, p < .001, and Group × Time, F(6, 168) = 11.18, p < .001, were significant. Post-hoc contrasts revealed that the heterosexual men had significantly stronger responses to the lesbian film than the homosexual and bisexual men during all 4 min, t(56) = 2.30–7.63, ps < .03. In addition, the bisexual men felt more aroused than the homosexual men during the fourth minute, t(56) = 2.18, p < .04.

Additional Analyses

To explore the association between the Kinsey scale and responses to the bisexual stimulus in more depth, we conducted a curve estimation analysis and predicted that the distribution of sexual responses to the bisexual stimulus, as a function of sexual orientation scores, should follow a negative quadratic function (i.e., the strongest responses should be found at the middle of the scale). The mean of the participants’ Kinsey scores for behavior and attraction was used as independent variable (cf. Rieger et al., 2005). The quadratic model was significant for both genital (see Fig. 3) and subjective responses, F(2, 56) = 4.35, p < .02; R 2 = .13, F(2, 56) = 8.09, p < .001, R 2 = .22, respectively.

We also conducted regression analyses with curve estimation following the approach used by Rieger et al. (2005). This approach differs from the one above in that it, instead of exploring responses across the Kinsey scale to a specific sexual stimulus, starts with the assumption that the difference between responses to heterosexual and homosexual stimuli should be smaller for bisexual than for homosexual and heterosexual men. Again, and consistent with Rieger et al. (2005), we used the mean of the participants’ Kinsey scores for behavior and attraction as the independent variable, and genital and subjective arousal as dependent variables. According to Rieger et al. (2005), bisexual men should, on average, show substantial arousal to both homosexual (e.g., male–male) and lesbian (e.g., female–female) stimuli, thus implying a negative quadratic relation between Kinsey scores and sexual arousal to the less arousing of these two types of stimuli. Similar to Rieger et al.’s findings, the quadratic model was not significant for either untransformed or transformed genital responses, F(2, 56) = 1.77, R 2 = .06; F(2, 55) = 2.47, R 2 = .09, respectively. However, it was significant for subjective sexual arousal, using both untransformed and transformed data, F(2, 55) = 15.61, p < .001; R 2 = .36, F(2, 55) = 15.56, p < .001, R 2 = .36, respectively.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to determine if self-identified bisexual men respond differently to bisexual, heterosexual, homosexual, and lesbian erotica from self-identified heterosexual and homosexual men. The results indicate that that this is indeed the case. Bisexual men did not differ in their responses to homosexual stimuli (depicting men engaging in sex) from homosexual men, and they did not differ in their responses to heterosexual (depicting two women engaged in sex with a man) and lesbian stimuli (depicting women engaging in sex) from heterosexual men. However, bisexual men displayed higher levels of both genital and subjective sexual arousal to a bisexual stimulus (depicting a man engaged in sex with both another man and a woman) than either homosexual or heterosexual men. In addition, bisexual men tended to show arousal levels to the lesbian stimulus that were midway between the levels shown by homosexual and heterosexual men.

This study, as have others before, presents a number of challenges that are unresolved and therefore warrant further research. Of primary importance is the question of how best to define, and operationalize, sexual orientation (cf. Mustanski, Chivers, & Bailey, 2002). We chose to rely on self-identification in this study, as it seems to capture the “gestalt” of one’s sexual orientation. But as others (e.g., Sell, 1997; Weinberg et al., 1994) have pointed out, self-identification may be influenced by a number of variables and is limited by its categorical nature. The use of the Kinsey scale has also been criticized. As Kinsey et al. (1948) pointed out, there may be discrepancies between one’s sexual history, one’s physical reactions to relevant stimuli, and one’s self-reported sexual orientation. In addition, the general custom has been to consider men with a “1” or a “5” on the Kinsey scale as heterosexual or homosexual, respectively, rather than calling such men bisexual. That is, most studies combine Kinsey scores of 0 and 1 to form a “heterosexual” group and Kinsey scores of 5 and 6 to form a “homosexual” group, but there is no clear empirical basis for such a procedure, and no psychophysiological studies have yet examined differences between men scoring a “0” or a “1” or between men scoring a “5” or a “6” on the Kinsey scale. Until such research is conducted, it appears that using self-identification will remain the most reasonable method of determining sexual orientation.

Also, the approach to the analysis of penile responses warrants some discussion. As we alluded to in the introduction, in some previous studies (e.g., Chivers et al., 2007; Rieger et al., 2005), penile strain gauge data were standardized, using z-score transformations, whereas we prefer to use non-standardized, calibrated data. In general, both approaches rely on the use of difference scores to index a response, usually by using the baseline as a reference. However, the use and presentation of calibrated data adds to the interpretability of research findings, as the transformation of sampled data to an absolute scale of penile circumference provides information on actual response levels. The use of calibrated data is further supported by the finding that circumference is highly correlated with rigidity (close to r = .9, see Levine & Carroll, 1994). In addition, much of the literature on correlations between genital responses and subjective sexual arousal, which tend to be relatively high in men (Chivers et al., 2010), is based on the use of calibrated, nontransformed penile response data. In contrast, there is substantial controversy in the general psychophysiological literature on the use of standardized scores (e.g., Blumenthal, Elden, & Flaten, 2004; Tassinary & Cacioppo, 2000). For instance, standardized scores are problematic when the dynamic range of responses is unknown or when this range—as tends to be the case with the use of explicit video clips—is substantial (cf. Blumenthal et al., 2004). Indeed, when comparing two subjects who have different ranges in responses, standardizing within each participant “will give the mistaken impression that the full range of potential response magnitudes was present in both participants” (Blumenthal et al., 2004).

From a historical perspective, z-scores have mainly been used in “phallometric” research (e.g., involving the evaluation of sex offenders) whereas calibrated data have traditionally been used and presented in research on sexual dysfunction and more basic psychophysiological studies on, for example, cognitive and affective determinants of sexual arousal. By implication, the history of z-scores in sexual studies is largely attached to the use of stimuli leading to small responses, whereas calibrated circumference data have been mainly used in studies incorporating stronger sexual stimuli, including sexually explicit films. In fact, Harris, Rice, Quinsey, Chaplin, and Earls (1992), who made a strong and often cited case for the use of standardization, based their recommendations on non-film data, with difference scores of only a mm or two (a degree of response many researchers nowadays would dismiss or consider a non-response). Z-scores have been said to lead to better discrimination between groups, but the findings of the current study, as is the case for numerous past studies using film stimuli, indicate that the use of non-standardized data does not prevent the detection of differences. In fact, we reran the analyses using z-scores, and the pattern of results was identical. Standardization of genital response data in women, especially in the case of vaginal photoplethysmography where response ranges are not well established, may be justifiable. For men, the standardization of penile circumference data, whether in place of or in addition to calibration, is not well established in the literature and, in our opinion, is not justified as a default procedure. More research is needed to improve our understanding of when z-score transformations are appropriate, or even preferred over the use of circumference data, when assessing men’s responses to film stimuli using penile strain gauges.

Another important question—at least for studies examining the association between sexual orientation and sexual arousal—is what constitutes a “bisexual” sexual stimulus. Relatively few psychophysiological studies exist on sexual arousal patterns in bisexual men. Studies that do exist have found little or no evidence for a bisexual orientation. However, we would argue that none of those studies included erotic stimuli that specifically targeted or were particularly relevant to the sexual preferences of bisexual men. Instead, the assumption underlying most of the previous research in this area, exploring the psychophysiology of sexual orientation, seems to be that bodies (i.e., the male/female body) might be the critical factor in differentiating arousal patterns in the laboratory. Such an assumption deemphasizes the behavioral content of the stimuli, which may be as relevant as the sex of the actors (however, see Chivers et al., 2007, who found, in a study that did not include bisexual men, that although the depiction of intercourse resulted in greater erectile responses than masturbation, the sex of actors was more important for men than for women). This issue extends to the question of the effects of presenting stimuli that depict behaviors engaged in by one, two, or even more individuals.

In addition, most existing research seems to equate bisexuality with being, in some way, both homosexual and heterosexual (e.g., bisexual men should respond equally strong to hetero- and homosexual stimuli). Rieger et al.’s (2005) findings, which we replicated, indicate that bisexual men, overall, do not respond equally to heterosexual and homosexual stimuli. However, this leaves the possibility that bisexuality is associated with the capacity to be sexually responsive to men and women but not necessarily to the same degree, at least not at any given point in time. More importantly, as we argue in this article, Rieger et al.’s findings do not address the possibility that bisexuality is associated with something unique, in terms of sexual preferences and responsivity. Our results clearly favor this interpretation, as they demonstrate that bisexual men respond strongly to stimuli that induce relatively low levels of response in both heterosexual and homosexual men.

Some limitations of the study should be acknowledged. First, although it did not prevent the detection of group differences in responses to the films, the bisexual group was relatively small in size. Also, the heterosexual and bisexual men reported a relatively high frequency of sexual intercourse. Future studies could compare, through a more targeted recruitment strategy, more and less sexually experienced men. Further, we used erotic stimuli that depicted men, women, or combinations of men and women. Although we attempted to make the stimuli as comparable as possible in terms of the actor configurations and the behaviors depicted, the reliance on commercially available videos limited our ability to do so. Thus, the lesbian stimulus depicted two rather than three women, a variable that might have contributed to the overall lower level of arousal to that video. In addition, no significant differences were found between sexual orientation groups for the heterosexual video, and it is not clear how to best explain this. In contrast to the bisexual and homosexual men, who showed, on average, responses of over 20 mm to either the bisexual or homosexual video, the heterosexual men did, overall, not get as aroused in this study (although their responses during the lesbian film stimulus were significantly higher than those of the other two groups). This points at the possibility that we failed to select a highly arousing heterosexual video. Moreover, when it comes to the bisexual video, because of the array of behaviors displayed in this video, it is difficult to know exactly which content elements were responsible for the best discrimination among groups. Previous studies have assumed that it is the body of the actors in stimuli that is the most important factor in differentiating groups of men with different sexual orientations. Freund et al., however, found that neither homosexual nor heterosexual men had an aversive response—assessed through penile detumescence and self-reported levels of disgust—to nonpreferred stimuli (slides of nudes of the opposite or same sex, respectively; Freund, Langevin, Cibiri, & Zajac, 1973; Freund, Langevin, & Zajac, 1974; however, see Israel & Strassberg, 2009, who found that heterosexual men were less comfortable viewing pictures of men than of women). This result hints that it may well be the interaction between the genders that is most differentiating. Future research could include the use of eye-tracking methods to explore such questions further.

Future studies comparing bisexual to heterosexual and homosexual men also might consider including stimuli depicting individual men or women masturbating. Hatfield et al. (1978) found that men reported higher levels of sexual arousal to female than to male masturbation films. Also, Mosher and O’Grady (1979) found that “viewing a film of homosexuality was both more sexually arousing and more eliciting of the negative affects of disgust, anger, shame, and guilt for men than was viewing a film of a male masturbating” (p. 870). More recently, Chivers et al. (2007) presented groups of homosexual and heterosexual men and women with a series of stimuli and found, among other things, that heterosexual men did not show a significant increase in penile response to male masturbation, and homosexual men not to female masturbation. However, none of these studies assessed the responses of bisexual men. As we alluded to above, a challenge for researchers using film stimuli involving multiple actors is to determine which sexual behaviors best represent “bisexual” behavior. It might be possible to show separate films of the same actor engaging sexually first with a member of the same and then the opposite sex (something we attempted to simulate in the present study, but in our case, both partners were present in the same situation), but such a procedure may have its own limitations, and it will be important to insure that participants recognize that it involves the same person in both films.

Previous research has shown that responses to erotic stimuli are influenced by affective and cognitive variables (Cranston-Cuebas & Barlow, 1990; Koukounas & McCabe, 2001; Mitchell, DiBartolo, Brown, & Barlow, 1998; Nobre et al., 2004; Peterson & Janssen, 2007). Clearly, the gender of the actors, their interaction, and the situational variables in an erotic stimulus could all influence the emotional valence and, perhaps most importantly for the current study, the meaning of the stimulus for the person watching the stimulus. Similarly, attention—and related processes such as ‘absorption’ (Koukounas & Over, 1997) and being able to imagine oneself as a participant in an erotic scene (e.g., Janssen, McBride, Yarber, Hill, & Butler, 2008)—has been found to contribute to whether or not a sexual response will occur (e.g., Barlow, 1986). This raises the question of whether responses to category-specific stimuli, in some direct or unmediated fashion, reflect what it is that turns one on (and, regarding the opposite, that stimuli that are not category-specific lack arousing properties) or whether some other, intervening processes are involved. Thus, future studies could explore to what degree responses to homosexual and heterosexual stimuli are mediated, regulated, or otherwise influenced by affective and attentional processes, including those that would be more indicative of the presence of inhibitory, instead of the absence of excitatory, influences (cf. Janssen & Bancroft, 2007).

The current study differed from the studies by McConaghy and Blaszczynski (1991) and Rieger et al. (2005) in that it did not examine the association between sexual orientation and sexual arousal by comparing men’s responses to different stimuli using only a within-subject approach (e.g., comparing bisexual men’s responses to “male” and “female” stimuli) but by comparing men’s responses to the same stimuli using a between-subject approach. The current study also differed from these studies—and from the study by Tollison et al. (1979) which did rely on a between-subject approach—in that it included a stimulus that more directly attempted to target the sexual responsivity often assumed to be representative of a bisexual orientation. Indeed, self-identified bisexual men in the present study strongly responded to a stimulus depicting a man engaging in sex with both a man and a woman, and this stimulus resulted in lower arousal in heterosexual and homosexual individuals. Although future research could improve on the procedures and stimuli used in the current study, our findings clearly suggest that bisexuality is associated with a unique and specific pattern of sexual arousal.

Notes

A random selection of five 1-min epochs (one from each of the erotic videos and one from the nonsexual video) from a random selection of 15 subjects were rescored by the first author, who was blind to the sexual orientation of the subjects. The correlation between the 75 original and the 75 rescored responses was r = .97, p < .001.

The analyses were repeated using standardized scores (within-subjects, prior to the calculation of difference scores) and the pattern of results was identical.

Correlations between the averaged erectile responses and reports of sexual arousal were r = .47, r = .44, r = .40, and r = .46 for heterosexual participants for the heterosexual, homosexual, bisexual, and lesbian stimuli, respectively. For the same stimuli, the correlations were r = .18, r = −.02, r = .54, and r = .19 for homosexual participants and r = .62, r = .77, r = .59, and r = .66 for bisexual participants.

References

Abel, G. G., Barlow, D. H., Blanchard, E. B., & Mavissakalian, M. (1975). Measurement of sexual arousal in male homosexuals: Effects of instructions and stimulus modality. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 4, 623–629.

Abel, G. G., Blanchard, E. B., & Barlow, D. H. (1981). Measurement of sexual arousal in several paraphilias: The effects of stimulus modality, instructional set and stimulus content. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 19, 25–33.

Abramson, P. R., & Mosher, D. L. (1975). Development of a measure of negative attitudes toward masturbation. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 43, 485–490.

Bancroft, J., Jones, H. G., & Pullan, B. P. (1966). A simple transducer for measuring penile erection with comments on its use in the treatment of sexual disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 4, 239–241.

Barlow, D. H. (1986). Causes of sexual dysfunction: The role of anxiety and cognitive interference. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 54, 140–148.

Blumenthal, T. D., Elden, A., & Flaten, M. A. (2004). A comparison of several methods used to quantify prepulse inhibition of eyeblink responding. Psychophysiology, 41, 326–332.

Chivers, M. L., Seto, M. C., & Blanchard, R. (2007). Gender and sexual orientation differences in sexual response to sexual activities versus gender of actors in sexual films. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 93, 1108–1121.

Chivers, M. L., Seto, M. C., Lalumiere, M. L., Laan, E., & Grimbos, T. (2010). Agreement of self-reported and genital measures of sexual arousal in men and women: A meta-analysis. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 39, 5–56.

Cranston-Cuebas, M. A., & Barlow, D. H. (1990). Cognitive and affective contributions to sexual functioning. Annual Review of Sex Research, 1, 119–161.

Freund, K., Langevin, R., Cibiri, S., & Zajac, Y. (1973). Heterosexual aversion in homosexual males. British Journal of Psychiatry, 122, 163–169.

Freund, K., Langevin, R., & Zajac, Y. (1974). Heterosexual aversion in homosexual males: A second experiment. British Journal of Psychiatry, 125, 177–180.

Gaither, G. A., & Plaud, J. J. (1997). The effects of secondary stimulus characteristics on men’s sexual arousal. Journal of Sex Research, 34, 231–236.

Harris, G. T., Rice, M. E., Quinsey, V. L., Chaplin, T. C., & Earls, C. (1992). Maximizing the discriminant validity of phallometric assessment data. Psychological Assessment, 4, 502–511.

Hatfield, E., Sprecher, S., & Traupmann, J. (1978). Men’s and women’s reactions to sexually explicit films: A serendipitous finding. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 7, 583–592.

High, R. W., Rubin, H. B., & Henson, D. (1979). Color as a variable in making an erotic film more arousing. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 8, 263–267.

Israel, E., & Strassberg, D. S. (2009). Viewing time as an objective measure of sexual interest in heterosexual men and women. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 38, 551–558.

Janssen, E., & Bancroft, J. (2007). The dual-control model: The role of sexual inhibition and excitation in sexual arousal and behavior. In E. Janssen (Ed.), The psychophysiology of sex (pp. 197–222). Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Janssen, E., Carpenter, D., & Graham, C. A. (2003). Selecting films for sex research: Gender differences in erotic film preference. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 32, 243–251.

Janssen, E., & Everaerd, W. (1993). Determinants of male sexual arousal. Annual Review of Sex Research, 4, 211–245.

Janssen, E., McBride, K., Yarber, W., Hill, B. J., & Butler, S. (2008). Factors that influence sexual arousal in men: A focus group study. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 37, 252–265.

Janssen, E., Prause, N., & Geer, J. H. (2007). The sexual response. In J. T. Cacioppo, L. G. Tassinary, & G. G. Berntson (Eds.), Handbook of psychophysiology (3rd ed., pp. 245–266). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Julien, E., & Over, R. (1988). Male sexual arousal across five modes of erotic stimulation. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 17, 131–143.

Kinsey, A. C., Pomeroy, W. B., & Martin, C. E. (1948). Sexual behavior in the human male. Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders.

Kinsey, A. C., Pomeroy, W. B., Martin, C. E., & Gebhard, P. H. (1953). Sexual behavior in the human female. Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders.

Koukounas, E., & McCabe, M. P. (2001). Sexual and emotional variables influencing sexual response to erotica: A psychophysiological investigation. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 30, 393–408.

Koukounas, E., & Over, R. (1997). Male sexual arousal elicited by film and fantasy matched in content. Australian Journal of Psychology, 49, 1–5.

Laumann, E. O., Gagnon, J. H., Michael, R. T., & Michaels, S. (1994). The social organization of sexuality: Sexual practices in the United States. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Levine, L. A., & Carroll, R. A. (1994). Nocturnal penile tumescence and rigidity in men without complaints of erectile dysfunction using a new quantitative analysis software. Journal of Urology, 152, 1103–1107.

Mavissakalian, M., Blanchard, E. B., Barlow, D. H., & Abel, G. G. (1975). Responses to complex erotic stimuli in homosexual and heterosexual males. British Journal of Psychiatry, 126, 252–257.

McConaghy, N. (1974). Measurements of change in penile dimensions. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 3, 381–388.

McConaghy, N., & Blaszczynski, A. (1991). Initial stages of validation by penile volume assessment that sexual orientation is distributed dimensionally. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 32, 52–58.

Mitchell, W. B., DiBartolo, P. M., Brown, T. A., & Barlow, D. H. (1998). Effects of positive and negative mood on sexual arousal in sexually functional males. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 27, 197–207.

Mosher, D. L. (1966). The development and multitrait-multimethod matrix analysis of three-measure of three aspects of guilt. Journal of Consulting Psychology, 30, 25–29.

Mosher, D. L., & Abramson, P. R. (1977). Subjective sexual arousal to films of masturbation. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 45, 796–807.

Mosher, D. L., & O’Grady, K. E. (1979). Homosexual threat, negative attitudes toward masturbation, sex guilt, and males’ sexual and affective reactions to explicit sexual films. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 47, 860–873.

Mustanski, B. S., Chivers, M. L., & Bailey, J. M. (2002). A critical review of recent biological research on human sexual orientation. Annual Review of Sex Research, 12, 89–140.

Nobre, P. J., Wiegel, M., Bach, A. K., Weisberg, R. B., Brown, T. A., Wincze, J. P., et al. (2004). Determinants of sexual arousal and the accuracy of its self-estimation in sexually functional males. Journal of Sex Research, 41, 363–371.

Peterson, Z., & Janssen, E. (2007). Ambivalent affect and sexual response: The impact of co-occurring positive and negative emotions on subjective and physiological sexual responses to erotic stimuli. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 36, 793–807.

Rieger, G., Chivers, M. L., & Bailey, J. M. (2005). Sexual arousal patterns of bisexual men. Psychological Science, 16, 579–584.

Sakheim, D. K., Barlow, D. H., Beck, J. G., & Abrahamson, D. J. (1985). A comparison of male heterosexual and male homosexual patterns of sexual arousal. Journal of Sex Research, 21, 183–198.

Sell, R. L. (1997). Defining and measuring sexual orientation: A review. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 26, 643–658.

Tassinary, G. G., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2000). The skeletomuscular system: Surface electromyography. In J. T. Cacioppo, L. G. Tassinary, & G. G. Berntson (Eds.), Handbook of psychophysiology (pp. 163–199). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Tollison, C. D., Adams, H. E., & Tollison, J. W. (1979). Cognitive and physiological indices of sexual arousal in homosexual, bisexual, and heterosexual males. Journal of Behavioral Assessment, 1, 305–314.

Vasey, M. W., & Thayer, J. F. (1987). The continuing problem of false positives in repeated measures ANOVA in psychophysiology: A multivariate solution. Psychophysiology, 24, 479–486.

Weinberg, M. S., Williams, C. J., & Pryor, D. W. (1994). Dual attraction: Understanding bisexuality. New York: Oxford University Press.

Wright, L. W., & Adams, H. E. (1994). Assessment of sexual preference using a choice reaction time task. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 16, 221–231.

Wright, L. W., & Adams, H. E. (1999). The effects of stimuli that vary in erotic content on cognitive processes. Journal of Sex Research, 36, 145–151.

Youn, G. (2006). Subjective sexual arousal in response to erotica: Effects of gender, guided fantasy, erotic stimulus, and duration of exposure. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 35, 87–97.

Zuckerman, M., Kolin, E. A., Price, L., & Zoob, I. (1964). Development of a sensation-seeking scale. Journal of Consulting Psychology, 28, 477–482.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported, in part, by Grant No. 2-29417 from the Indiana State University Research Committee. Jerome Cerny is now retired from Indiana State University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cerny, J.A., Janssen, E. Patterns of Sexual Arousal in Homosexual, Bisexual, and Heterosexual Men. Arch Sex Behav 40, 687–697 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-011-9746-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-011-9746-0