Abstract

The performance of foreign subsidiaries (FS) has been the topic of studies since the beginning of the international business (IB) field. However, research findings are contradictory because of the disparate foci of individual studies. In this review paper, we first identify key determinants of the performance of FS through a structured content analysis of 73 articles and 679 relationships since the year 2000. Second, we explain the effects of each determinant, and perform meta-analysis to determine which relationships are statistically meaningful. Third, we compare the effects of determinants across different combinations of home and host contexts, based on which, we provide possible explanations of previous inconsistent findings. We conclude by offering new theoretical directions to better understand determinants of the performance of FS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

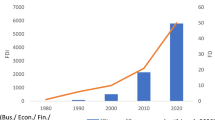

The growing trend of foreign direct investment (FDI) has been well recognized in recent decades. Within this trend, Asia,Footnote 1 “with its FDI flows surpassing half a trillion US dollars, remain [s] the largest FDI recipient region in the world, accounting for one third of global FDI flows” (UNCTAD, 2016: 2). Many foreign subsidiaries (FS) are established and operate in Asia, and FDI outflows from Asia have been sufficiently substantial to attract the attention of academic researchers (e.g., Chittoor, Sarkar, Ray, & Aulakh, 2009; Elango & Pattnaik, 2007; Luo & Zhang, 2016) and policy makers (e.g., the Foreign Investment Commission in the United States and the Ministry of Commerce in China). Thus, Asia provides an ideal context for investigating FDI activity.

Understanding what determines the performance of FS is fundamental to FDI research because it relates to one of the “big questions” in international business (IB) about the determinants of the international failure and success of firms (Peng, 2004). The performance of FS is also a major concern of managers of multinational enterprises (MNEs) because it directly relates to the appropriateness of their international strategy and has a profound influence on their global operations. Although often offering important insight, the focus of the extant literature is dispersed among several domains, with many inconsistencies in the findings remaining unresolved. This fragmentation of research may be partially due to the complexities FS confront in external (e.g., dually embedded in the home and host countries) and internal (e.g., interdependencies of the parent MNEs and peer subsidiaries) environments (Kostova, Roth, & Dacin, 2008; Phene & Almeida, 2008). Although previous studies have examined many different determinants, particular determinants are found to have inconsistent effects on FS performance. For example, the effect of cultural distance between home and host countries on FS performance has been found to be positive (e.g., Gaur, Delios, & Singh, 2007; Riaz, Rowe, & Beamish, 2014), negative (e.g., Fang, Jiang, Makino, & Beamish, 2010; Luo & Park, 2001), and non-significant (e.g., Peng & Beamish, 2014). The same is true of the effect of parent MNE’s technological resources. While researchers such as Delios and Beamish (2001), Fang et al. (2010), and Kim, Lu, and Rhee (2012) have observed a positive relationship between the technological resources of parent MNEs and the survival and performance of FS, others have found a negative (e.g., Demirbag, Apaydin, & Tatoglu, 2011; Lavie & Miller, 2008), or non-significant relationship (e.g., Belderbos & Zou, 2007; Nguyen & Rugman, 2015).

To identify and resolve the inconsistencies in the literature, this study combines content analysis and meta-analysis. First, using content analysis, we identify the key determinants of FS performance examined by previous studies. Second, where empirically feasible, we conduct a meta-analysis to find the overall effect of each determinant. Based on these findings, our analyses further reveal that different home–host-country contexts have good potential to explain the inconsistent effects of the same antecedent. For example, while the effect of institutional development in the host country on FS performance is negative for FDI from Asia, it is non-significant for FDI within Asia.Footnote 2

Our review not only helps define the boundaries of several theory-predicted relationships, but also opens avenues for future research. We provide possible explanations for the inconsistencies in the extant literature, and new research opportunities for future studies. This study also serves as a good reference for MNE managers because it provides an extensive summary of all potential drivers of the success of their foreign investments.

Methodology

We use a combination of content analysis and meta-analysis to conduct our literature review. Content analysis allows us to identify key information about the relationship between specific determinants and FS performance examined by previous studies, while meta-analysis provides empirical evidence for the identified relationships, as well as opportunities to explore moderating effects.

In the first step, we conducted a structured content analysis of a set of articles in prominent management and IB journals published from 2000 to October of 2017.Footnote 3 In this step, we first searched for articles empirically examining FS-related questions using the following keywords: “foreign subsidiary,” “foreign affiliate,” “international joint venture,” “international M&A,” “green-field investment” and “entry mode.” We collected 424 articles through this search. We then manually checked each article to determine the following three issues: (1) whether the article was empirical; (2) whether the dependent variable was performance related; (3) whether the study included an Asian country as the destination or source country of FDI.

We narrowed the selection of our dependent variable to the three most commonly-used measures of FS performance: economic metrics including ROA, ROS, and profitability, among others (e.g., Chan, Makino, & Isobe, 2010; Zhang, Li, Hitt, & Cui, 2007), survival of the subsidiary (e.g., Song, 2014), and satisfaction measures (e.g., Fey, Morgulis-Yakushev, Park, & Björkman, 2009; Hsieh & Rodrigues, 2014; Luo, Shenkar, & Nyaw, 2001). For each article, we coded the independent and dependent variables, the home and host countries of the sampled FS, and the effect size and significance of the relationships under investigation. Our final sample comprised 73 articles, with a total of 679 relationships assessed. Of the three authors of the present paper, two performed the necessary coding activities and the third reviewed all the articles. Any discrepancies in coding were discussed among the authors until consensus was reached. Table 1 presents the summary of our content analysis.

In the second step, we conducted meta-analysis. Meta-analysis is particularly appropriate when empirical findings yield inconsistent results (Wijk, Jansen, & Lyles, 2008). Although review studies based on content analysis can map previous studies, they are subject to several of limitations: (1) they can discuss only the key findings the authors report; (2) they are subject to sampling bias (Dalton, Aguinis, Dalton, Bosco, & Pierce, 2012) or to the presence of the Type II errors (i.e., lack of sufficient statistical power to determine the rejection of the hypothesized relationship) (Combs, Ketchen, Crook, & Roth, 2011); (3) they cannot distinguish between the importance of studies, ending up in comparing the findings of studies using smaller samples with those using larger samples (Combs et al., 2011). To overcome these limitations of review studies based on content analysis, we present meta-analytic effect size of each relationship between determinants and FS performance. This approach provides two benefits to the reader: (1) it offers a sense of the strength of the effect size for each relationship; (2) it allows readers to identify which relationship(s) are non-significant, suggesting the presence of possible moderators and thus presenting areas of future inquiry.

The meta-analysis was performed using the Comprehensive Meta-Analysis software package (Borenstein, Hedges, Higgins, & Rothstein, 2005). Following recent best practice (Aguinis, Beaty, Boik, & Pierce, 2005; Aguinis, Gottfredson, & Wright, 2011), we performed the analysis at the effect-size level rather than at the article level because this approach captures both the heterogeneity of the effect-size estimates and the unique information for each relationship that would otherwise have been missing (Van Mierlo, Vermunt, & Rutte, 2009). We did not make any adjustments for measurement error to provide more conservative estimates. We report in the text only effect sizes from the random-effect analysis in cases where at least three studies are available for the specific relationship. Further, we compare the relationships between identified determinants and FS performance among different directions of investments (i.e., investment to, from and within Asia). Inconsistent findings across different categories provide a foundation for future research (Table 2).

Determinants of foreign subsidiary performance

This section presents our main findings. Based on content analysis, we find that previous studies have examined determinants of FS performance in four main areas: parent-firm characteristics, subsidiary characteristics, parent-subsidiary relationship, and country-level factors. In the following, we first provide a brief summary of each main area, presenting the key issues concerned, after which we discuss the findings of our meta-analysis.

Parent-firm characteristics

Parent-firm factors have long been recognized as key determinants of FS performance because the parent MNE usually provides critical resources (e.g., technology, information, talent) that support the operations of FS. Studies have examined the effects of parent-MNE international experience, technological capability, age, and size on FS performance. For FS involving multiple parent firms (e.g., a joint venture [JV] between foreign parent and local parent), the extent of complementarities and cooperation between different partners have shown as important determinants of FS performance.

Parent-firm international experience

International experience is considered a function of the extent to which a firm has previously operated in international markets (Lu & Beamish, 2001). Previous international experience has been considered an important factor for improving FS success because it cultivates the capability of managing foreign operations (Chan, Isobe, & Makino, 2008), and handling risks and uncertainties in foreign markets (Delios & Beamish, 2001; Makino & Delios, 1996). However, the empirical results of previous studies show inconclusive effects of parent-firm international experience, with findings of a positive, negative and null effect (e.g., Clegg, Lin, Voss, Yen, & Shih, 2016; Lavie & Miller, 2008; Merchant & Schendel, 2000). In general, our meta-analysis reveals a positive and significant effect of parent-firm international experience on FS performance (.04*).Footnote 4 However, the significant effect is not that strong for MNEs to Asia (.05†), and further this significant effect does not hold for MNEs from Asia. These findings may suggest that international experience is more difficult to transfer across different regions, and therefore, the benefits firms derive from prior internationalization are limited when conducting cross-regional investment.

Parent-firm technological capability

Technological capability is a function of the proprietary activities that generate technological knowledge (Chatterjee & Wernerfelt, 1991; Song, Droge, Hanvanich, & Calatone, 2005). The technological capability of the parent firm is an important contributor to FS performance (Delios & Beamish, 2001; Fang, Wade, Delios, & Beamish, 2007), because these capabilities are often less imitable and incur low depreciation costs during cross-country transfer, and thus lay foundations for FS competitive advantage. While some studies find benefits from parent-firm technological capability (e.g., Choi & Beamish, 2013; Fang et al., 2010), our meta-analysis did not yield any statistically significant findings (.02, n.s.). A possible explanation for this insignificant result may be that it is not easy to transfer resources and capabilities from headquarters to FS (Fang et al., 2007; Miller, 2003; Simonin, 1999; Szulanski & Jensen, 2006). This factor requires greater research attention, not only on firms’ rare and valuable resources and capabilities, but also on the extent to which these resources and capabilities can be transferred, imitated, or substituted across countries (Tsoukas, 1996).

Parent-firm age

Parent-firm age has been considered an important factor influencing FS performance because age often indicates reliability, market credibility and the experience-based capabilities of a firm (Baum & Shipilov, 2006; Henderson, 1999). In addition, the age of the parent MNE contributes to its external legitimacy, which may also spill over to the FS (Lu & Xu, 2006). However, there is little consensus in the literature on the effect of parent-firm age on FS performance, with findings being positive, negative or null (e.g., Clegg et al., 2016; Dutta & Beamish, 2013; Lu & Xu, 2006). Our meta-analysis supports an overall positive effect of parent-firm age on FS performance (.04**), and the result holds for investment from Asia (.03**) and investment within Asia (.06+).

Parent-firm size

The size of the parent firm reflects the amount of available resources and capabilities that can be exploited in new markets (Hymer, 1976). As with parent-firm age, parent-firm size is also an important contributing factor to external legitimacy (Lu & Xu, 2006) that can send positive signals to potential customers (Mudambi & Zahra, 2007). The resource availability and legitimacy spillover from the parent-firm facilitate the performance of FS. In general, our meta-analysis shows a positive effect of parent-firm size on FS performance (.10***), although some studies we coded did not find a significant effect (e.g., Kim et al., 2012; Lu & Xu, 2006; Sim & Ali, 2000). The positive result is quite consistent across different home–host-country combinations (.14** for MNEs to Asia; .11*** for MNEs from Asia; .06** for MNEs within Asia).

Partner relationship

The relationship between partners from the home and host countries can also determine the success or failure of the focal FS. Our content analysis found that previous studies mainly investigate the effect of partner relationship by considering two aspects: the goal similarity and resource complementarity between partners. High levels of goal similarity and resource complementarity promote FS performance because they can create a situation of mutual cooperation and forbearance (Buckley & Casson, 1976; Sim & Ali, 2000) that facilitates the operations of the FS. However, the meta-analysis did not find any significant effects of goal similarity and resource complementarity for MNEs investments to Asia (−.06, n.s. and −.07, n.s., respectively). A possible explanation may be that the effect of partner relationships on FS performance is contingent on external environments such as market and political uncertainties that shape inter-firm collaboration (Luo & Park, 2004; Park, Chen, & Gallagher, 2002).

Subsidiary characteristics

As legally standalone enterprises, FS cultivate their own resources and capabilities that can significantly shape their performance. Key subsidiary-level determinants examined by previous studies include FS age, FS size and FS technological resources.

FS technological resources

The technological resources of an FS refer to its research and development (R&D) intensity (Lee, Park, Ghauri, & Park, 2014), learning capabilities (Wang, Tong, Chen, & Kim, 2009), and exploitation and exploration capabilities (Zhan & Chen, 2013). Technological resources are key determinants of FS performance because they not only determine the absorption and deployment of resources transferred from the parent MNE, but also influence the exploration and utilization of resources based in the host country. The knowledge transferred from the parent MNE often provides competitive resources for the FS in the host country. However, this transferred knowledge may not necessarily be assimilated and exploited by the FS given the tacit nature of knowledge. The higher R&D intensity and learning capabilities of the FS facilitate the transformation of knowledge from the parent MNE and thus promote the financial performance of the FS (Chi & Zhao, 2014). Moreover, FS also benefit from resources available in the host country. FS with higher technological resources have a greater capacity to absorb and redeploy local resources and thus gain higher performance (Zhang et al., 2007). Consistent with these arguments, our meta-analyses show a strong and positive effect of FS technological resources on FS performance (.26***). While this finding holds well for FDI to Asia and from Asia, the effect is much stronger for Western MNEs investing in Asia (.37**) than it is for Asian MNEs investing in other countries (.13**). This result may imply that while subsidiaries of Western MNEs mainly compete on technological resources, subsidiaries of Asian MNEs may also compete on other resources (e.g., relationship-based capabilities).

FS age

The age of the FS reflects how long it has operated in a host country. FS age is a key determinant of FS performance because it represents the host-country experience of the FS and its accumulated knowledge of the business environment (Nguyen & Rugman, 2015). Due to the liability of newness (Stinchcombe, 1965), a younger FS with little experience in a host country will often confront more challenges and thus perform worse than an experienced FS. Consistent with these arguments, our meta-analysis shows a positive and significant effect of FS age on FS performance (.03**), and this finding holds strongly for Western MNEs investing in Asia (.10***) or Asian MNEs investing in other countries (.04***). However, we did not find a significant effect of FS age for Asian MNEs investing in the home region (−.09, n.s.). This result implies that host-country experience and accumulated knowledge are more important for cross-regional investment than for the intra-regional investment.

FS size

The size of an FS affects its financial performance because it reflects both the investment amount and parent MNE’s interests in the focal subsidiary (Lee & Song, 2012). Parent MNEs depend more on larger subsidiaries (Prahalad & Doz, 1987), and thus often pay more attention to these subsidiaries (Bouquet, Morrison, & Birkinshaw, 2009) and provide better support to large rather than small FS. Such resource commitment and attention from the parent MNE promote FS performance. As expected, our meta-analysis reveals an overall positive and significant effect of FS size on FS performance (.05*). However, this finding holds only for foreign investments by Western MNEs to Asia (.07**), but not for those by Asian MNEs (.04, n.s.). This result may imply a unique characteristic of FDI from Asian MNEs in that the success of their FS does not depend on utilizing resources and support from the parent firm, but rather depends on resource exploration at the subsidiary level.

Parent-subsidiary relationship

The relationship between the parent MNE and its FS exerts a strong influence on FS performance and has attracted substantial research attention. A large body of research focuses on governance issues, including the entry mode adopted by the MNE to establish its FS in the host country, the amount of ownership the MNE shares with local partners (if any), and the control versus autonomy the MNE grants to the focal subsidiary. Another body of research focuses on human-resource management (HRM) practices that the parent firm imposes on the FS, including the use of expatriate.

Entry mode and MNE ownership

Studies have examined which establishment mode (e.g., acquisition versus greenfield investment) (Belderbos, 2003; Oehmichen & Puck, 2016; Song, 2014) and equity mode (minority, majority JV, or wholly owned FS) (Gaur et al., 2007; Gaur & Lu, 2007) lead to higher FS performance. However, these studies have reached largely inconclusive results. Some studies suggest that greater ownership control by the parent MNE is better for FS performance because greater foreign ownership reflects a higher commitment from the parent MNE, which will increase resource transfer, and that the MNE having greater control reduces the opportunistic behavior of local partners (e.g., Dhanaraj & Beamish, 2009). However, other research suggests that greater ownership by the MNE may reduce the incentive of local partners to contribute to the focal FS, thus inhibiting collaboration, which could harm FS performance. Researchers also suggest that different entry modes represent different levels of investment irreversibility (versus flexibility) (e.g., Belderbos & Zou, 2007; Song, 2014), and the costs and benefits of different entry modes may be largely conditioned on external uncertainty. Given these inconclusive results, recent studies suggest that different entry modes may not have direct effects on FS performance because the entry mode itself is endogenous rather than exogenous. MNEs determine the entry mode of FS after evaluating alternative options based on factors such as their resource condition, purpose of international investment, and home and host countries. Thus, in the condition that MNEs do not make unfit or biased decisions, entry mode should not have direct effects on FS performance. Consistent with this discussion, our meta-analysis does not show any significant overall effects of entry mode (.02, n.s. for wholly owned subsidiary [WOS] versus JV; −.02, n.s. for mergers and acquisitions [M&A] versus greenfield) and MNE ownership level (.01, n.s.) on FS performance. Although with an overall insignificant effect, our analyses show apparent variations across different investment directions. For example, while a wholly owned structure has a negative effect on Western MNEs investing to Asia (−.01***), higher level of ownership has a positive effect on Asian MNEs investing in other countries (.03**), indicating that home-country and host-country conditions may act as potential moderators.

Subsidiary governance

The issue of subsidiary governance involves the extent of autonomy MNEs grant to their FS. FS autonomy refers to the decision-making rights of subsidiaries in relation to their parent MNEs (McDonald, Warhurst, & Allen, 2008). High FS autonomy represents high level of freedom of FS to make a range of decisions (e.g., business plans, supply-chain management, HRM, strategy implementation) without necessarily referring to headquarters. Studies suggest that subsidiary autonomy is positively related to FS performance because the subsidiary manager often has deeper insight into the idiosyncratic nature of the specific host country than does the parent MNEs and thus, FS with greater autonomy are more likely to make effective and efficient decisions that promote financial performance (Nguyen & Rugman, 2015). Our meta-analysis shows an overall positive but not significant effect of FS governance on FS performance (.02, n.s.), with variability across Western MNEs and Asian MNEs.

Human-resources practice

One of the key issues in the relationship between the parent firm and the FS is the expatriate strategy. Studies suggest that utilizing an expatriate workforce is of strategic importance for FS performance because expatriates facilitate knowledge transfer from parent MNE (Wang, Tong, & Koh, 2004; Wang et al., 2009). Due to cultural and institutional distance between the home and host countries, and the tacit nature of transferred knowledge, FS often cannot fully understand and assimilate the knowledge from the parent MNE. FS with skilled expatriates are more likely to benefit from the resources of parent MNEs and thus improve their competitive advantage (Wang et al., 2009). Consistent with this discussion, our meta-analysis shows a strong positive effect of expatriate utilization on FS performance (.11***), and the positive finding holds for different investment directions.

Country-level factors

Country-level factors refer to determinants of FS performance arising from home-country and host-country characteristics and differences. The home country of a parent MNE influences FS performance because it offers opportunities and resources such as technological resources or access to capital markets to the MNE, and cultivates the MNE’s capabilities to conduct foreign operations and deal with uncertainty in the host country, thus leading to improved FS performance (e.g., Clegg et al., 2016; Mudambi & Zahra, 2007). The host-country environment in which the FS is embedded also explicitly shapes the performance of the FS. Studies have investigated the influence of local institutional development (e.g., Chan et al., 2008) and market attractiveness (e.g., Merchant & Schendel, 2000; Zeng, Shenkar, Song, & Lee, 2013) on FS performance. Research attention has also been dedicated to differences between the home and host countries, among which the key focus has been on cultural distance (e.g., Hennart & Zeng, 2002; Pothukuchi, Damanpour, Choi, Chen, & Park, 2002) and institutional distance (e.g., Demirbag et al., 2011; Gaur & Lu, 2007).

Country of origin

The country of origin of an MNE has strategic implications for the performance of its FS because the home-country environment significantly shapes the skills, capabilities, resources and ways of doing business (Wan & Hoskisson, 2003). MNEs coming from relatively developed countries are more likely to have higher technological capability and advanced managerial skills that contribute to FS performance (Chen, Li, Shapiro, & Zhang, 2014; Sethi & Elango, 2000). Individual studies have found positive or null relationships between MNE country of origin and FS performance (e.g., Cuervo-Cazurra & Genc, 2008; Delios & Beamish, 2001; Mudambi & Zahra, 2007; Zhao & Luo, 2002). Our meta-analysis finds only marginal support for the positive relationship between MNE home country and FS performance (.06†). The directionality of the FDI seems to explain the differences in findings: FS of MNEs located in advanced nations benefit more from the home-country environment (.07***) than do FS of MNEs located in Asia (from: .10, n.s.; within: .04, n.s.). These findings partially support the “escaping perspective” (Witt & Lewin, 2007), which states that institutional constraints in emerging countries inhibit firms from developing a competitive advantage at home, therefore motivating them to search for opportunities abroad to circumvent the disadvantages generated by home-country institutions (Boisot & Meyer, 2008; Child & Rodrigues, 2005; Hoskisson, Wright, Filatotchev, & Peng, 2013; Peng, Sun, & Blevins, 2011).

Level of institutional development of host country

The level of institutional development in a host country reflects the efficiency of its formal regulations, legal systems, and political regimes that support market-based transactions (North, 1990; Peng, Wang, & Jiang, 2008). Studies suggested a positive relationship between the level of institutional development and FS performance, although they have arrived at non-significant (e.g., Child, Chung, & Davies, 2003; Merchant & Schendel, 2000; Nguyen & Rugman, 2015) or even negative findings (Chan et al., 2008). Our meta-analysis supports the null findings (−.01, n.s.), but the direction of investment appears to moderate such a relationship. That is, FS of Western MNEs operating in Asia do not appear to benefit from a more advanced intuitional environment (.07, n.s.), nor do the FS of Asian MNEs operating within Asia (.00, n.s.). In contrast, firms coming from Asia seem to underperform in more advanced institutional environments (−.09**). A possible explanation is that MNEs from emerging countries are accustomed to operating in weak institutional environments in which regulations are not clear and enforceability is not consistent. This means that when operating in intuitional environments where regulations and enforceability are well established, such MNEs suffer because of the cost associated with engaging with more complex rules and public scrutiny.Footnote 5

Market attractiveness of host country

Local-market attractiveness has generally been considered a driver of FS performance. Market size, market growth, limited competition and availability of resources (Belderbos & Zou, 2007; Child et al., 2003; Garg & Delios, 2007; Ng, Lau, & Nyaw, 2007; Zeng et al., 2013) should positively drive firm performance. Although our meta-analysis does not derive a general effect (.01, n.s.), it shows clear variations across different directions of investments. Indeed, local-market attractiveness seems to drive FS performance in Asia only for those from Asian MNEs (.17**), but it does not for Western MNEs investing in Asia (.56, n.s.) or for Asian MNEs investing in Western countries (−.06, n.s.). One possible explanation is that the cost of doing business in an unfamiliar environment can dilute the benefits arising from operating in an attractive market.

Home-host cultural distance

The greater the cultural distance between two countries, the greater the costs for the MNE in adapting to the host market because of inconsistencies in values and intra-organizational conflict (Schneider & De Meyer, 1991; Tihanyi, Griffith, & Russell, 2005). This view is shared by several scholars (e.g., Fang et al., 2010; Hennart & Zeng, 2002; Pothukuchi et al., 2002). In general, our meta-analysis result supports this perspective (−.02†), even though the significance level is low. The negative effect of cultural distance on FS performance is much stronger for Western MNEs investing in Asia (−.05*), while it is not significant for MNEs from Asia (.01, n.s.). One of the important reasons why the argument of the higher costs caused by cultural distance does not apply to FS from Asia might be that the motivation of FS from Asia is mainly about exploration, and the higher distance might stand for more potential opportunities to learn new capabilities.

Home-host institutional distance

Differences in institutions between the home and host country such as normative and regulative institutions (Gaur et al., 2007; Riaz et al., 2014) or economic freedom (Demirbag et al., 2011) have received relatively less research attention compared with cultural distance in IB. We were able to collect studies looking at Japanese MNEs only, which postulate a positive relationship between institutional distance and FS performance. However, our meta-analysis does not find a statistically significant effect for this relationship (.03, n.s.).

Directions for future research

Completing the research landscape

Our review has covered almost twenty years of research on the determinants of FS performance, and has evidences that some of these determinants have been assessed many times with consistent or inconsistent findings, while others have been assessed by a limited number of studies in the Asian context. Reassessing the relationships that we have analyzed in similar and dissimilar contexts is important in allowing the field to mature. The replication or repetition of studies (Bettis, Helfat, & Shaver, 2016) is also necessary in creating cumulative knowledge, and in assessing whether prior studies are sufficiently accurate in factors such as measurement and design (Boyd, Gove, & Hitt, 2005).

Based on our literature review, FS performance has been measured by economic metrics in 61 studies, by survival of the subsidiary in 16 studies, but has been measured using satisfaction measures in only eight studies, showing a clear under-examination of subjective measures of FS performance.Footnote 6 Archival measures suffer from problems of attenuation and measurement error (Boyd et al., 2005). Future studies would benefit from examining primary studies because these can better detect the relationship under investigation. Further, the strength of the antecedents-outcome relationship might vary across different kinds of outcomes studied (Delios & Beamish, 2001). In this study, we could not make meaningful comparisons across outcomes due to data limits, leaving it as a promising future line of inquiry.Footnote 7 In addition, it has also been argued that there is little attention devoted to FS growth once they are established, which can be considered an important omission in current IB research (for an exception, see Kim & Gray, 2008) because growth can be an important contributor to MNEs’ employment and sales growth complementing new subsidiary investments (Belderbos & Zou, 2007). To complete the research landscape of FS performance, future research can pay greater attention to subjective measures of FS performance, drivers of FS growth, and comparisons across different performance measures.

Completion of the research landscape on FS performance should create an opportunity to focus on context in academic research. In the articles reviewed by this study, context has generally been neglected. This is also an important omission because our review demonstrates that context is an important element in explaining inconclusive results and that the mixed evidence for theoretical predictions is probably due to an under-contextualization of previous research. Given that the utility of a theoretical perspective is a function of its contextual sensitivity (McKelvey, 2002), we advise future research to better explore the interplay between theory and context to examine how the latter contributes to explaining the boundaries of established theories. In addition, researchers should recognize the specificities in Asia that warrant further theorization (Li, 2016; Peng, 2005). For example, the state itself is more proactive and engaged with private business affairs compared with the role of the state in Western economies (Carney, Gedajlovic, & Yang, 2009; Witt & Redding, 2014). Such difference creates dynamics that can be captured only by research theorizing the local context. Thus, we renew the call for more theory developed on the Asian context and Asian phenomena, rather than simply using Asia as a research setting (Bruton & Lau, 2008; Meyer, 2006). We provide several potential research questions that should be tested in different contexts (see Table 3).

Underexplored areas

Our review finds several factors that are critical to FS performance but received little research attention. In this section, we introduce some of these under-examined areas to inspire future research.

Micro-foundations of FS performance

Most of the literature we have reviewed focuses on the firm or the country level of analysis, and treats the decision-making process as a black box. The decision to invest in a foreign country offers a unique opportunity to study the micro-foundations of strategy itself (Felin & Foss, 2005) and how the parent firm’s decisions affect the subsidiary. For example, FS offer the opportunity to assess which levels of analysis offer the most performance-related explanatory power and to identify the conditions that make those levels of analysis significant. Such research would represent a great advance in the variance-decomposition studies conducted thus far (e.g., Christmann, Day, & Yip, 1999; Makino, Isobe, & Chan, 2004). Furthermore, as the decision-making process is influenced by emotions and beliefs, factors that shape people’s risk propensity (Powell, Lovallo, & Fox, 2011) should be addressed in the research. The exploration of such internal factors can help explain why certain FS decide to conform with the local environment, while others decide to diversify and preserve their distinctiveness, thus influence their performance. Prior IB research is mainly grounded in rational-choice models and pays little attention to the role of managerial characteristics (Nielsen & Nielsen, 2011). In contrast, based on the upper echelons theory, observable demographic characteristics of top executives can be used to infer psychological cognitive biases and values, and may therefore serve as powerful predictors of strategies (Hambrick & Mason, 1984). The micro-foundations, which can be explored through the eyes of the chief executive officer (CEO) and managerial team of an FS that is subjugated by the parent firm’s decisions, would offer a rich opportunity for assessing how the subsidiary manager reacts and negotiates when it disagrees with the parent firm’s decisions. Along the same line of enquiry, it would also be beneficial to address how individual interpretations of the environment differ, and examine how specific environmental changes (e.g., Brexit) shape individual and collective responses.

Portfolio view of FS performance

Although several IB scholars conceptualize an MNE as a network or portfolio of FS (Ghoshal & Bartlett, 1990; Nachum & Song, 2011), previous studies tend to examine FS performance from a dyadic view that focuses on the interactions between a specific dyad between MNE and a foreign subsidiary, rather than from a portfolio view that focuses on the interactions among different FS within the MNE network. For future research, a portfolio view of FS performance may contribute to IB literature because the predominant dyadic view tends to consider each foreign investment decision as independent, while largely neglecting the interdependencies between different international decisions. Interdependencies between different FS are critical to the understanding of FS performance because studies as well as anecdotal evidence have demonstrated that MNEs engage in switching operations across different FS to utilize arbitrage opportunities and circumvent adverse changes in a specific FS or host country (Belderbos & Zou, 2009; Belderbos, Tong, & Wu, 2014). Due to such arbitraging activities, the performance of a specific FS should be evaluated interdependently within the portfolio of the parent MNE rather than independently because sometimes the FS performance of a specific subunit may be sacrificed to reach group-level efficiency. This portfolio view may change some of our understanding on the value-creation role of each FS because the value of each subunit may not only come from maximizing its own performance, but also from providing arbitrage and option values to the whole group of FS (Nachum & Song, 2011).

Non-market strategy of FS

The FS of MNEs are often accused of social misdeeds, including environmental pollution, product-quality flaws, and abusive labor practices. These accusations can easily become public crises that are exposed in the national media, causing long-term and serious financial and reputational damage (Zhao, Park, & Zhou, 2014). The negative effects of the irresponsible behavior of a specific FS not only hurt its own performance, but also that of the parent MNE and other affiliated units of the entire organizational group. Given the profound effects of FS negative social behavior, the current literature pays scarce attention to the non-market strategies of FS and the performance outcomes of such non-market behavior. Our review reveals that previous studies have investigated various factors that predict FS performance from an economic rationale (Cuervo-Cazurra & Dau, 2009; Roth & O’Donnell, 1996; Zhang et al., 2007). Although FS performance is influenced by these economic factors, it is important to note that economic activities do not occur in a barren social context (Granovetter, 1985). It is crucial for firms to maintain efficiency and legitimacy to survive and succeed in a foreign environment (Chan & Makino, 2007; DiMaggio & Powell, 1983; Scott, 2001). Some recent studies have begun to emphasize the role of corporate social responsibility (CSR) as a non-market strategy that can be employed to overcome the liabilities of “foreignness” (Marano, Tashman, & Kostova, 2017) and to achieve social and political legitimacy (Hond, Rehbein, Bakker, & Lankveld, 2014; Marquis & Qian, 2014; Wang & Qian, 2011). By integrating institutional theory and stakeholder theory (Doh & Guay, 2006), future studies could explore how FS adopt non-market strategies to achieve legitimacy in the host market within different institutional environments.

Institutional entrepreneurship

Most research on institutional theory has focused on the effect of the institution on the FS. An alternate perspective is that of institutional entrepreneurs, who are actors leveraging resources to either transform existing institutions or create new ones (DiMaggio, Hargittai, Celeste, & Shafer, 2004). Research in this area explores the nature of the “institutional work” needed to create, maintain, transform, or disrupt institutions (Hardy & Maguire, 2008). FS are in a privileged position to act as institutional entrepreneurs. The headquarters cannot align all FS to each institutional environment in which the FS operate because doing so would create an overly complex internal bureaucracy (Kostova et al., 2008). Therefore, an FS can be actively engaged in transforming or disrupting the host institutions under pressure from headquarters. FS from Western countries with better developed institutions are more likely to have a stronger effect on the deepening of pro-market reforms in emerging markets (Cuervo-Cazurra, 2016). However, the risks and benefits of institutional entrepreneurship for FS, and the underlying processes and mechanisms remain unknown.

Research-design opportunities

Given the different methodological approaches used for studying FS performance (47 articles used archival data and 26 articles used surveys), we identify several opportunities for improving the methodological rigor of future studies on FS performance.

Endogeneity issues

Only a minority (31%) of the studies using archival sources considered in this review assessed the potential pitfalls arising from endogeneity. Even though this lack of attention is in line with the recent development of macro research (Boyd & Solarino, 2016), research should focus more on issues of endogeneity. For example, Tan (2009) showed that endogeneity issues affect the relationship between entry-mode choices and subsequent FS performance. Once endogeneity is dealt with, this relationship becomes non-significant. Other concerns arise on the quality of the endogeneity controls. For example, differences in findings have emerged between studies assessing the technology base of the parent firm and FS performance. Among these studies, some use a one-year lagged dependent variable and others adopt more elaborate techniques (e.g., two-stage least squares) (e.g., Fang et al., 2010). Fortunately, however, there are several examples of studies that adopted a variety of solid approaches to endogeneity control in the IB literature (e.g., Chang, Chung, & Moon, 2013; Nguyen & Rugman, 2015; Riaz et al., 2014).

Survey bias: Common-method bias and social desirability

Fortunately, 75% of the survey studies assessed the presence of common-method bias, which refers to the variance generated due to the method rather than due to the constructs the measures represent, thus generating inflated results (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, & Podsakoff, 2003). Most of the research reviewed controlled ex-post for this bias, but a minority offset this problem in the survey design by including multiple items or distributing questions associated with the independent and dependent variables in a manner undetectable by the respondent (e.g., Li & Lee, 2015; Williams & Du, 2014). Among the studies that discussed this bias, none found it had a relevant effect on the study. A closely related issue is social-desirability bias, which refers to systematic error being generated in self-reported measures because of the desire of respondents to avoid embarrassment and to project a favorable image of themselves (or of their firm) to others (Fisher, 1993). Little research has attempted to deal with this issue, and the solution adopted in some studies was simply to guarantee anonymity to the respondents. However, this solution appears to be suboptimal because prior studies have provided evidence of how different cultures show notable differences in giving socially desirable answers (Bernardi, 2006; Ralston, Gustafson, Cheung, & Terpstra, 1993), which means that future studies should consider this issue to strengthen the validity of the results.

Multilevel analysis

FS are embedded in multilevel external environments, including the regional, national, and subnational environments (Hitt, 2016). However, most current studies focus on the effects of the national-level environment. Beugelsdijk and Mudambi (2013: 415) suggested that researchers should consider “moving from the current dominance of analyses based on country means to a study of IB activities where the complex intermingling of different geographic scales (global, supra-regional, national and subnational) is taken into account.” It is important to consider multiple levels of effects when examining the drivers of FS performance. Arregle, Miller, Hitt, and Beamish (2013) found that both national and regional institutional environments are significant determinants of MNE location choices. However, the influence of multiple levels of effects on FS performance remains underexplored.

Contingency design

Most studies reviewed examined a direct, linear effect between an independent variable and a specific outcome. In other areas of business research, contingency models have often provided a richer understanding of a research topic. Contingency models fall into several categories, from simple interaction effects to more elaborated forms (Venkatraman, 1989). Our review reveals that only a minority of moderators have been tested in research, and even less studies tested for mediating effects. Thus, one methodological opportunity is to take a more systematic approach to identifying possible moderators, and their effects in different contexts. Studies assessing mediation were primarily interested in assessing how the antecedents of learning affect firm performance and the relationships mediated by the practice of knowledge transfer (Lane, Salk, & Lyles, 2001; Wang et al., 2009).

Qualitative research opportunities

While IB research has a long history of conducting qualitative studies (e.g., Kindleberger, 1956; Wilkins, 1970), currently, authors rarely perform qualitative research in IB studies (Birkinshaw, Brannen, & Tung, 2011). We noted that this problem is further worsen with regards to FS research. However, qualitative studies about FS performance can enlighten research questions that cannot be answered through quantitative research because qualitative studies are better suited to capturing the complexity of the relationship between the MNE headquarters and the FS. For example, recent studies have furthered our understanding of which processes managers implement to overcome foreign-market disadvantages (Li, Easterby-Smith, Lyles, & Clark, 2016), how firms proactively manage their international joint venture termination (Westman & Thorgren, 2016), and how knowledge is transferred between headquarters and the FS (Hong, Easterby-Smith, & Snell, 2006; Hong & Nguyen, 2009). Qualitative studies offer a unique opportunity to explore the inner processes of MNEs and the micro-foundations of a firm’s international strategy (Felin, Foss, & Ployhart, 2015; Foss & Pedersen, 2016), as well as how the relationship between the different actors of an MNE jointly shape overall FS performance. Second, as the complexity increases (e.g., due to increased cultural distance) (e.g., Drogendijk & Holm, 2012), qualitative studies become even more valuable. For example, qualitative research can examine the managerial dynamics between different headquarters (e.g., HSBC and Lenovo have multiple headquarters), between main headquarters and regional headquarters, and between semiautonomous subsidiaries. Such research can also examine the moderating role of culture on the influence of individual behavior and motivation on firm strategy and performance. Finally, qualitative studies are well suited to test and develop multiple theories concurrently (Doz, 2011; Van de Ven, 2007). Qualitative research that engages in the exploration of a new phenomenon can approach it through a variety of theoretical lenses, systematically comparing and contrasting how the different theoretical lenses can explain the phenomenon. New insights about boundary conditions, limitations, moderators, mediators will arise when research is conducted in this manner.

Practical implications

The performance of foreign subsidiaries is one of key concerns of MNE managers. Through structured content analysis and meta-analysis, our study provides practical implications for MNE managers about key factors that matter for their FS performance. First, despite previous mixed and inconsistent findings, our meta-analysis revealed the importance of investing in technological resources at the FS level as technological resources (and competences) promote FS performance substantially, and account for a greater contribution to FS performance than the resources of the parent firm do. Therefore, FS managers should actively invest in developing FS technological resources. Our meta-analysis result also showed the importance of utilizing expatriates to help FS to better transfer and assimilate the knowledge from the parent, as we found consistent positive effect of expatriate utilization on FS performance for different investment directions. Therefore, FS managers should consider how to effectively interact with the parent firm through the expatriate link. Second, we call for managers to pay attention to the location of the FS in relation to investment because contextual factors can significantly alter the relevance and effects of the determinants of FS performance discussed in this paper. The same strategy may generate very different impact on FS performance for different home-host-country contexts. For example, the higher level of ownership as entry mode can generate positive impact on FS from Asia, but not for FS in Asia. In general, our study serves as a guiding map for MNE managers to pin point drivers of their FS performance.

Conclusions

Since the origin of the IB field, FS performance has been a core topic for research. The literature spans many decades, and many determinants of FS performance have been assessed, leading to disparate findings in the literature and questions remaining unanswered. We propose a synthesis of the determinants of FS performance, and have provided evidence of areas where further research is needed. Our synthesis has provided evidence of the importance of the direction of investments in IB research, a factor that has been underestimated in current literature. We conclude with a number of possible areas for future research to extend our understanding, along with suggestions for improving the methodological rigor of FS studies.

Notes

Although a universally accepted definition of the term “Asia” has not yet been reached, a broad view of geographic Asia is the region that is bounded on the east by the Pacific Ocean, on the south by the Indian Ocean, and on the north by the Arctic Ocean. In Bruton and Lau’s (2008) review article on Asian management research, they exclude the Middle East, the Caucasus, Russia and Turkey to avoid confounding findings. For the purposes of our review, we follow Bruton and Lau’s (2008) understanding of Asia, with the exception that we include Russia.

We refer to Western MNEs investing in Asia as “investment to Asia,” Asian MNEs investing in Asia as “investment within Asia,” and Asian MNEs investing outside of Asia as “investment from Asia.”

The following journals were reviewed: Academy of Management Journal; Journal of Management; Journal of Management Studies; Organization Science; Strategic Management Journal; Asia Pacific Journal of Management; International Business Review; Journal of International Management; Journal of International Business Studies; Journal of World Business; Management International Review; Management and Organization Review.

† p < .10; * p < .05; ** p < .01; *** p < .001; “n.s.” stands for non-significant.

As an example, the Italian banking authority recently fined the Bank of China because the internal processes of its Italian subsidiary were not adequate for dealing with money-laundering issues (Reuters, 2017).

A few papers used more than one type of measurement of FS performance.

We would like to thank one of our anonymous reviewers for pointing out this element.

References

* Indicates an article included in the meta-analysis

Aguinis, H., Beaty, J. C., Boik, R. J., & Pierce, C. A. 2005. Effect size and power in assessing moderating effects of categorical variables using multiple regression: A 30-year review. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(1): 94–107.

Aguinis, H., Gottfredson, R. K., & Wright, T. A. 2011. Best practice recommendations for estimating interaction effects using meta-analysis. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 32(8): 1033–1043.

Arregle, J. L., Miller, T. L., Hitt, M. A., & Beamish, P. W. 2013. Do regions matter? An integrated institutional and semiglobalization perspective on the internationalization of MNEs. Strategic Management Journal, 34(8): 910–934.

*Barbopoulos, L., Marshall, A., Macinnes, C., & Mccolgan, P. 2014. Foreign direct investment in emerging markets and acquirers’ value gains. International Business Review, 23(3): 604–619.

Baum, J. A. C., & Shipilov, A. V. 2006. Ecological approaches to organizations. In S. Clegg, C. Hardy, T. Lawrence, & W. Nord (Eds.). Handbook of organization studies: 55–110. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Belderbos, R. 2003. Entry mode, organizational learning, and R&D in foreign affiliates: Evidence from Japanese firms. Strategic Management Journal, 24(3): 235–259.

Belderbos, R., Tong, T. W., & Wu, S. 2014. Multinationality and downside risk: The roles of option portfolio and organization. Strategic Management Journal, 35(1): 88–106.

Belderbos, R., & Zou, J. 2007. On the growth of foreign affiliates: Multinational plant networks, joint ventures, and flexibility. Journal of International Business Studies, 38(7): 1095–1112.

Belderbos, R., & Zou, J. 2009. Real options and foreign affiliate divestments: A portfolio perspective. Journal of International Business Studies, 40(4): 600–620.

Bernardi, R. A. 2006. Associations between Hofstede’s cultural constructs and social desirability response bias. Journal of Business Ethics, 65(1): 43–53.

Bettis, R. A., Helfat, C. E., & Shaver, J. M. 2016. The necessity, logic, and forms of replication. Strategic Management Journal, 37(11): 2193–2203.

Beugelsdijk, S., & Mudambi, R. 2013. MNEs as border-crossing multi-location enterprises: The role of discontinuities in geographic space. Journal of International Business Studies, 44(5): 413–426.

Birkinshaw, J., Brannen, M. Y., & Tung, R. L. 2011. From a distance and generalizable to up close and grounded: Reclaiming a place for qualitative methods in international business research. Journal of International Business Studies, 42(5): 573–581.

Boisot, M., & Meyer, M. W. 2008. Which way through the open door? Reflections on the internationalization of Chinese firms. Management and Organization Review, 4(3): 349–365.

Borenstein, M., Hedges, L., Higgins, J., & Rothstein, H. 2005. Comprehensive meta-analysis version 2. Englewood: Biostat.

Bouquet, C., Morrison, A., & Birkinshaw, J. M. 2009. International attention and multinational enterprise performance. Journal of International Business Studies, 40(1): 108–131.

Boyd, B. K., Gove, S., & Hitt, M. A. 2005. Consequences of measurement problems in strategic management research: The case of Amihud and Lev. Strategic Management Journal, 26(4): 367-375.

Boyd, B. K., & Solarino, A. M. 2016. Ownership of corporations: A review, synthesis, and research agenda. Journal of Management, 42(5): 1282–1314.

Bruton, G. D., & Lau, C. M. 2008. Asian management research: Status today and future outlook. Journal of Management Studies, 45(3): 636–659.

Buckley, P. J., & Casson, M. C. 1976. Future of the multinational enterprise. London: Macmillan.

Carney, M., Gedajlovic, E., & Yang, X. 2009. Varieties of Asian capitalism: Toward an institutional theory of Asian enterprise. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 26(3): 361–380.

*Chan, C. M., Isobe, T., & Makino, S. 2008. Which country matters? Institutional development and foreign affiliate performance. Strategic Management Journal, 29(11): 1179–1205.

Chan, C. M., & Makino, S. 2007. Legitimacy and multi-level institutional environments: Implications for foreign subsidiary ownership structure. Journal of International Business Studies, 38(4): 621–638.

Chan, C. M., Makino, S., & Isobe, T. 2010. Does subnational region matter? Foreign affiliate performance in the United States and China. Strategic Management Journal, 31(11): 1226–1243.

Chang, S. J., Chung, J., & Moon, J. J. 2013. When do wholly owned subsidiaries perform better than joint ventures?. Strategic Management Journal, 34(3): 317-337.

Chatterjee, S., & Wernerfelt, B. 1991. The link between resources and type of diversification: Theory and evidence. Strategic Management Journal, 12(1): 33–48.

Chen, V. Z., Li, J., Shapiro, D. M., & Zhang, X. 2014. Ownership structure and innovation: An emerging market perspective. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 31(1): 1-24.

Chi, T., & Zhao, Z. J. 2014. Equity structure of MNE affiliates and scope of their activities: Distinguishing the incentive and control effects of ownership. Global Strategy Journal, 4(4): 257-279.

*Child, J., Chung, L., & Davies, H. 2003. The performance of cross-border units in China: A test of natural selection, strategic choice and contingency theories. Journal of International Business Studies, 34(3): 242–254.

Child, J., & Rodrigues, S. B. 2005. The internationalization of Chinese firms: A case for theoretical extension?. Management and Organization Review, 1(3): 381-410.

Chittoor, R., Sarkar, M. B., Ray, S., & Aulakh, P. S. 2009. Third-world copycats to emerging multinationals: Institutional changes and organizational transformation in the Indian pharmaceutical industry. Organization Science, 20(1): 187–205.

*Choi, C. B., & Beamish, P. W. 2004. Split management control and international joint venture performance. Journal of International Business Studies, 35(3): 201–215.

*Choi, C. B., & Beamish, P. W. 2013. Resource complementarity and international joint venture performance in Korea. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 30(2): 561–576.

Christmann, P., Day, D., & Yip, G. S. 1999. The relative influence of country conditions, industry structure, and business strategy on multinational corporation subsidiary performance. Journal of International Management, 5(4): 241–265.

*Chung, C. C., & Beamish, P. W. 2005. The impact of institutional reforms on characteristics and survival of foreign subsidiaries in emerging economies. Journal of Management Studies, 42(1): 35–62.

*Clegg, J., Lin, H. M., Voss, H., Yen, I. F., & Shih, Y. T. 2016. The OFDI patterns and firm performance of Chinese firms: The moderating effects of multinationality strategy and external factors. International Business Review, 25(4): 971–985.

Combs, J. G., Ketchen, D. J., Jr., Crook, T. R., & Roth, P. L. 2011. Assessing cumulative evidence within ‘macro’ research: Why meta-analysis should be preferred over vote counting. Journal of Management Studies, 48(1): 178-197.

Cuervo-Cazurra, A. 2016. Corruption in international business. Journal of World Business, 51(1): 35–49.

Cuervo-Cazurra, A., & Dau, L. A. 2009. Promarket reforms and firm profitability in developing countries. Academy of Management Journal, 52(6): 1348–1368.

Cuervo-Cazurra, A., & Genc, M. 2008. Transforming disadvantages into advantages: Developing-country MNEs in the least developed countries. Journal of International Business Studies, 39(6): 957–979.

Dalton, D. R., Aguinis, H., Dalton, C. M., Bosco, F. A., & Pierce, C. A. 2012. Revisiting the file drawer problem in meta-analysis: An assessment of published and nonpublished correlation matrices. Personnel Psychology, 65(2): 221–249.

*Delios, A., & Beamish, P. W. 2001. Survival and profitability: The roles of experience and intangible assets in foreign subsidiary performance. Academy of Management Journal, 44(5): 1028–1038.

*Demirbag, M., Apaydin, M., & Tatoglu, E. 2011. Survival of Japanese subsidiaries in the Middle East and North Africa. Journal of World Business, 46(4): 411–425.

*Dhanaraj, C., & Beamish, P. W. 2004. Effect of equity ownership on the survival of international joint ventures. Strategic Management Journal, 25(3): 295–305.

*Dhanaraj, C., & Beamish, P. W. 2009. Institutional environment and subsidiary survival. Management International Review, 49(3): 291–312.

DiMaggio, P., Hargittai, E., Celeste, C., & Shafer, S. 2004. From unequal access to differentiated use: A literature review and agenda for research on digital inequality. In K. Neckerman (Ed.). Social inequality. New York: Russell Sage.

DiMaggio, P., & Powell, W. W. 1983. The iron cage revisited: Collective rationality and institutional isomorphism in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48(2): 147–160.

Doh, J. P., & Guay, T. R. 2006. Corporate social responsibility, public policy, and NGO activism in Europe and the United States: An institutional-stakeholder perspective. Journal of Management Studies, 43(1): 47-73.

Doz, Y. 2011. Qualitative research for international business. Journal of International Business Studies, 42(5): 582–590.

Drogendijk, R., & Holm, U. 2012. Cultural distance or cultural positions? Analysing the effect of culture on the HQ-subsidiary relationship. International Business Review, 21(3): 383-396.

*Dutta, D. K., & Beamish, P. W. 2013. Expatriate managers, product relatedness, and IJV performance: A resource and knowledge-based perspective. Journal of International Management, 19(2): 152–162.

Elango, B., & Pattnaik, C. 2007. Building capabilities for international operations through networks: A study of Indian firms. Journal of International Business Studies, 38(4): 541–555.

*Fang, E., & Zou, S. 2010. The effects of absorptive and joint learning on the instability of international joint ventures in emerging economies. Journal of International Business Studies, 41(5): 906–924.

*Fang, E. E., & Zou, S. 2009. Antecedents and consequences of marketing dynamic capabilities in international joint ventures. Journal of International Business Studies, 40(5): 742–761.

*Fang, Y., Jiang, G. L. F., Makino, S., & Beamish, P. W. 2010. Multinational firm knowledge, use of expatriates, and foreign subsidiary performance. Journal of Management Studies, 47(1): 27–54.

*Fang, Y., Wade, M., Delios, A., & Beamish, P. W. 2007. International diversification, subsidiary performance, and the mobility of knowledge resources. Strategic Management Journal, 28(10): 1053–1064.

*Fang, Y., Wade, M., Delios, A., & Beamish, P. W. 2013. An exploration of multinational enterprise knowledge resources and foreign subsidiary performance. Journal of World Business, 48(1): 30–38.

Felin, T., & Foss, N. J. 2005. Strategic organization: A field in search of micro-foundations. Strategic Organization, 3(4): 441.

Felin, T., Foss, N. J., & Ployhart, R. E. 2015. The microfoundations movement in strategy and organization theory. Academy of Management Annals, 9(1): 575-632.

*Fey, C. F., & Björkman, I. 2001. The effect of human resource management practices on MNC subsidiary performance in Russia. Journal of International Business Studies, 32(1): 59–75.

*Fey, C. F., Morgulis-Yakushev, S., Park, H. J., & Björkman, I. 2009. Opening the black box of the relationship between HRM practices and firm performance: A comparison of MNE subsidiaries in the USA, Finland, and Russia. Journal of International Business Studies, 40(4): 690–712.

Fisher, R. J. 1993. Social desirability bias and the validity of indirect questioning. Journal of Consumer Research, 20(2): 303–315.

Foss, N. J., & Pedersen, T. 2016. Microfoundations in strategy research. Strategic Management Journal, 37(13): E22–E34.

*Gao, G. Y., Pan, Y., Lu, J., & Tao, Z. 2008. Performance of multinational firms’ subsidiaries: Influences of cumulative experience. Management International Review, 48(6): 749–768.

*Garg, M., & Delios, A. 2007. Survival of the foreign subsidiaries of TMNCs: The influence of business group affiliation. Journal of International Management, 13(3): 278–295.

*Gaur, A. S., Delios, A., & Singh, K. 2007. Institutional environments, staffing strategies, and subsidiary performance. Journal of Management, 33(4): 611–636.

*Gaur, A. S., & Lu, J. W. 2007. Ownership strategies and survival of foreign subsidiaries: Impacts of institutional distance and experience. Journal of Management, 33(1): 84–110.

Ghoshal, S., & Bartlett, C. A. 1990. The multinational corporation as an interorganizational network. Academy of Management Review, 15(4): 603–626.

*Giachetti, C. 2016. Competing in emerging markets: Performance implications of competitive aggressiveness. Management International Review, 56(3): 325–352.

*Gong, Y. 2006. The impact of subsidiary top management team national diversity on subsidiary performance: Knowledge and legitimacy perspectives. Management International Review, 46(6): 771–790.

*Gong, Y., Shenkar, O., Luo, Y., & Nyaw, M. K. 2005. Human resources and international joint venture performance: A system perspective. Journal of International Business Studies, 36(5): 505–518.

Granovetter, M. 1985. Economic action and social structure: The problem of embeddedness. American Journal of Sociology, 91(3): 481–510.

Hambrick, D. C., & Mason, P. A. 1984. Upper echelons: The organization as a reflection of its top managers. Academy of Management Review, 9: 193–206.

Hardy, C., & Maguire, S. 2008 . Institutional entrepreneurship. In R. Greenwood, C. Oliver, R. Suddaby, & K. Sahlin-Andersen (Eds.). Handbook of organizational institutionalism: 198-217. London: Sage.

*He, X., Zhang, J., & Wang, J. 2015. Market seeking orientation and performance in China: The impact of institutional environment, subsidiary ownership structure and experience. Management International Review, 55(3): 389–419.

Henderson, A. D. 1999. Firm strategy and age dependence: A contingent view of the liabilities of newness, adolescence, and obsolescence. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(2): 281–314.

*Hennart, J. F., & Zeng, M. 2002. Cross-cultural differences and joint venture longevity. Journal of International Business Studies, 33(4): 699–716.

Hitt, M. A. 2016. International strategy and institutional environments. Cross Cultural & Strategic Management, 23(2): 206–215.

Hond, F., Rehbein, K. A., Bakker, F. G., & Lankveld, H. K. V. 2014. Playing on two chessboards: Reputation effects between corporate social responsibility (CSR) and corporate political activity (CPA). Journal of Management Studies, 51(5): 790–813.

Hong, J. F., Easterby-Smith, M., & Snell, R. S. 2006. Transferring organizational learning systems to Japanese subsidiaries in China. Journal of Management Studies, 43(5): 1027–1058.

Hong, J. F., & Nguyen, T. V. 2009. Knowledge embeddedness and the transfer mechanisms in multinational corporations. Journal of World Business, 44(4): 347–356.

Hoskisson, R. E., Wright, M., Filatotchev, I., & Peng, M. W. 2013. Emerging multinationals from mid-range economies: The influence of institutions and factor markets. Journal of Management Studies, 50(7): 1295–1321.

*Hsieh, L. H., & Rodrigues, S. B. 2014. Revisiting the trustworthiness-performance-governance nexus in international joint ventures. Management International Review, 54(5): 675-705.

*Hsu, C. W., Chen, H., & Caskey, D. 2017. Local conditions, entry timing, and foreign subsidiary performance. International Business Review, 26(3): 544–554.

*Hsu, S. T. H., Iriyama, A., & Prescott, J. E. 2016. Lost in translation or lost in your neighbor’s yard: The moderating role of leverage and protection mechanisms for the MNC subsidiary technology sourcing-performance relationship. Journal of International Management, 22(1): 84-99.

Hymer, S. 1976. The international operations of national firms: A study of direct foreign investment. Cambridge: MIT Press.

*Kang, J., Lee, J. Y., & Ghauri, P. N. 2017. The interplay of Mahalanobis distance and firm capabilities on MNC subsidiary exits from host countries. Management International Review, 57(3): 379-409.

*Kim, Y., & Gray, S. J. 2008. The impact of entry mode choice on foreign affiliate performance: The case of foreign MNEs in South Korea. Management International Review, 48(2): 165–188.

*Kim, Y. C., Lu, J. W., & Rhee, M. 2012. Learning from age difference: Interorganizational learning and survival in Japanese foreign subsidiaries. Journal of International Business Studies, 43(8): 719–745.

Kindleberger, C. P. 1956. The terms of trade: A European case study. New York: Wiley.

Kostova, T., Roth, K., & Dacin, M. T. 2008. Institutional theory in the study of multinational corporations: A critique and new directions. Academy of Management Review, 33(4): 994–1006.

Lane, P. J., Salk, J. E., & Lyles, M. A. 2001. Absorptive capacity, learning, and performance in international joint ventures. Strategic Management Journal, 22(12): 1139–1161.

*Lavie, D., & Miller, S. R. 2008. Alliance portfolio internationalization and firm performance. Organization Science, 19(4): 623–646.

*Lee, J. Y., Park, Y. R., Ghauri, P. N., & Park, B. I. 2014. Innovative knowledge transfer patterns of group-affiliated companies: The effects on the performance of foreign subsidiaries. Journal of International Management, 20(2): 107–123.

*Lee, S. H., & Hong, S. J. 2012. Corruption and subsidiary profitability: US MNC subsidiaries in the Asia Pacific region. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 29(4): 949–964.

*Lee, S. H., & Song, S. 2012. Host country uncertainty, intra-MNC production shifts, and subsidiary performance. Strategic Management Journal, 33(11): 1331–1340.

*Li, J., & Lee, R. P. 2015. Can knowledge transfer within MNCs hurt subsidiary performance? The role of subsidiary entrepreneurial culture and capabilities. Journal of World Business, 50(4): 663–673.

*Li, S., Easterby-Smith, M., Lyles, M. A., & Clark, T. 2016. Tapping the power of local knowledge: A local-global interactive perspective. Journal of World Business, 51(4): 641-653.

Li, X. 2016. The danger of Chinese exceptionalism. Management and Organization Review, 12(4): 815–816.

*Li, X., Liu, X., & Thomas, H. 2013. Market orientation, embeddedness and the autonomy and performance of multinational subsidiaries in an emerging economy. Management International Review, 53(6): 869–897.

*Li, X., & Sun, L. 2017. How do sub-national institutional constraints impact foreign firm performance?. International Business Review, 26(3): 555-565.

*Liu, X., Gao, L., Lu, J., & Lioliou, E. 2016a. Does learning at home and from abroad boost the foreign subsidiary performance of emerging economy multinational enterprises?. International Business Review, 25(1): 141-151.

*Liu, X., Gao, L., Lu, J., & Lioliou, E. 2016b. Environmental risks, localization and the overseas subsidiary performance of MNEs from an emerging economy. Journal of World Business, 51(3): 356–368.

Lu, J. W., & Beamish, P. W. 2001. The internationalization and performance of SMEs. Strategic Management Journal, 22(6): 565–586.

*Lu, J. W., & Ma, X. 2008. The contingent value of local partners’ business group affiliations. Academy of Management Journal, 51(2): 295–314.

*Lu, J. W., & Xu, D. 2006. Growth and survival of international joint ventures: An external-internal legitimacy perspective. Journal of Management, 32(3): 426-448.

*Luo, Y., & Park, S. H. 2001. Strategic alignment and performance of market-seeking MNCs in China. Strategic Management Journal, 22: 141–155.

*Luo, Y., & Park, S. H. 2004. Multiparty cooperation and performance in international equity joint ventures. Journal of International Business Studies, 35(2): 142–160.

*Luo, Y., Shenkar, O., & Nyaw, M. K. 2001. A dual parent perspective on control and performance in international joint ventures: Lessons from a developing economy. Journal of International Business Studies, 32(1): 41–58.

Luo, Y., & Zhang, H. 2016. Emerging market MNEs: Qualitative review and theoretical directions. Journal of International Management, 22(4): 333–350.

*Lyles, M., Li, D., & Yan, H. 2014. Chinese outward foreign direct investment performance: The role of learning. Management and Organization Review, 10(3): 411–437.

Makino, S., & Delios, A. 1996. Local knowledge transfer and performance: Implications for alliance formation in Asia. Journal of International Business Studies, 27(5): 905–927.

Makino, S., Isobe, T., & Chan, C. M. 2004. Does country matter?. Strategic Management Journal, 25(10): 1027-1043.

Marano, V., Tashman, P., & Kostova, T. 2017. Escaping the iron cage: Liabilities of origin and CSR reporting of emerging market multinational enterprises. Journal of International Business Studies, 48(3): 386–408.

Marquis, C., & Qian, C. 2014. Corporate social responsibility reporting in China: Symbol or substance?. Organization Science, 25(1): 127-148.

McDonald, F., Warhurst, S., & Allen, M. 2008. Autonomy, embeddedness and the performance of foreign owned subsidiaries. Multinational Business Review, 16(3): 73–92.

McKelvey, B. 2002. Model-centered organizational science epistemology. In J. A. C. Baum (Ed.). Companion to organizations: 752–780. Oxford: Blackwell.

Merchant, H., & Schendel, D. 2000. How do international joint ventures create shareholder value?. Strategic Management Journal, 21(7): 723-737.

*Meschi, P. X., Phan, T. T., & Wassmer, U. 2016. Transactional and institutional alignment of entry modes in transition economies. A survival analysis of joint ventures and wholly owned subsidiaries in Vietnam. International Business Review, 25(4): 946–959.

Meyer, K. E. 2006. Asian management research needs more self-confidence. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 23(2): 119-137.

Miller, D. 2003. An asymmetry-based view of advantage: Towards an attainable sustainability. Strategic Management Journal, 24(10): 961–976.

Mohr, A., Wang, C., & Goerzen, A. 2016. The impact of partner diversity within multiparty international joint ventures. International Business Review, 25(4): 883–894.

*Mudambi, R., & Zahra, S. A. 2007. The survival of international new ventures. Journal of International Business Studies, 38(2): 333–352.

Nachum, L., & Song, S. 2011. The MNE as a portfolio: Interdependencies in MNE growth trajectory. Journal of International Business Studies, 42(3): 381–405.

*Newburry, W., Zeira, Y., & Yeheskel, O. 2003. Autonomy and effectiveness of equity international joint ventures (IJVs) in China. International Business Review, 12(4): 395–419.

*Ng, P. W. K., Lau, C. M., & Nyaw, M. K. 2007. The effect of trust on international joint venture performance in China. Journal of International Management, 13(4): 430–448.

Nguyen, Q. T., & Rugman, A. M. 2015. Internal equity financing and the performance of multinational subsidiaries in emerging economies. Journal of International Business Studies, 46(4): 468–490.

Nielsen, B. B., & Nielsen, S. 2011. The role of top management team international orientation in international strategic decision-making: The choice of foreign entry mode. Journal of World Business, 46(2): 185–193.

North, D. C. 1990. A transaction cost theory of politics. Journal of Theoretical Politics, 2(4): 355–367.

*Oehmichen, J., & Puck, J. 2016. Embeddedness, ownership mode and dynamics, and the performance of MNE subsidiaries. Journal of International Management, 22(1): 17–28.

Park, S. H., Chen, R. R., & Gallagher, S. 2002. Firm resources as moderators of the relationship between market growth and strategic alliances in semiconductor start-ups. Academy of Management Journal, 45(3): 527–545.

*Peng, G. Z., & Beamish, P. W. 2014. The effect of host country long term orientation on subsidiary ownership and survival. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 31(2): 423–453.

Peng, M. W. 2004. Identifying the big question in international business research. Journal of International Business Studies, 35(2): 99–108.

Peng, M. W. 2005. Perspectives—From China strategy to global strategy. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 22(2): 123-141.

Peng, M. W., Sun, S. L., & Blevins, D. P. 2011. The social responsibility of international business scholars. Multinational Business Review, 19(2): 106–119.

Peng, M. W., Wang, D. Y., & Jiang, Y. 2008. An institution-based view of international business strategy: A focus on emerging economies. Journal of International Business Studies, 39(5): 920–936.

Phene, A., & Almeida, P. 2008. Innovation in multinational subsidiaries: The role of knowledge assimilation and subsidiary capabilities. Journal of International Business Studies, 39(5): 901–919.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. 2003. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5): 879–903.

*Pothukuchi, V., Damanpour, F., Choi, J., Chen, C. C., & Park, S. H. 2002. National and organizational culture differences and international joint venture performance. Journal of International Business Studies, 33(2): 243–265.

Powell, T. C., Lovallo, D., & Fox, C. R. 2011. Behavioral strategy. Strategic Management Journal, 32(13): 1369–1386.

Prahalad, C. K., & Doz, Y. L. 1987. The multinational mission: Balancing local demands with global vision. New York: Free Press.

Ralston, D. A., Gustafson, D. J., Cheung, F. M., & Terpstra, R. H. 1993. Differences in managerial values: A study of US, Hong Kong and PRC managers. Journal of International Business Studies, 24(2): 249–275.

Reuters. 2017. Bank of China pays 600,000 euros to close Italy money laundering case. http://www.reuters.com/article/bankofchina-italy/bank-of-china-pays-600000-euros-to-close-italy-money-laundering-case-idUSL8N1G25RB, Accessed Feb. 17, 2017.