Abstract

The growing awareness of and regulations related to environmental sustainability have invoked the concept of green human resource management (GHRM) in the search for effective environmental management (EM) within organizations. GHRM research raises new, increasingly salient questions not yet studied in the broader human resource management (HRM) literature. Despite an expansion in the research linking GHRM with various aspects of EM and overall environmental performance, GHRM’s theoretical foundations, measurement, and the factors that give rise to GHRM (including when and how it influences outcomes) are still under-specified. This paper, seeking to better understand research opportunities and advance theoretical and empirical development, evaluates the emergent academic field of GHRM with a narrative review. This review highlights an urgent need for refined conceptualization and measurement of GHRM and develops an integrated model of the antecedents, consequences and contingencies related to GHRM. Going beyond a function-based perspective that focuses on specific HRM practices and building on advances in the strategic HRM literature, we discuss possible multi-level applications, the importance of employee perceptions and experiences related to GHRM, contextual and cultural implications, and alternative theoretical approaches. The detailed and focused review provides a roadmap to stimulate the development of the GHRM field for scholars and practicing managers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Asia now faces a new economic reality that is increasingly influenced by resource constraints and environmental challenges (Angel & Rock, 2000; Marquis, Jackson, & Li, 2015). The region, amid the growing awareness of environmental sustainability, is experiencing sweeping changes that give rise to the urgency of reforming models of economic growth and development. These changes involve environmental movements that have resulted in national governments setting more ambitious environmental targets and increased transnational collaboration. In 2016, for example, the 21 member nations of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) forum agreed to tariff cuts on 54 environmentally friendly goods—the first multi-lateral tariff-cutting arrangement in 20 years. The goal of such tariff cutting is to support access to clean technologies, facilitate the doubling of renewable energy use in the Asia-Pacific region by 2030, and reduce energy intensity by 45% by 2035 (APEC, 2016). This commitment to building environmentally sustainable economies has been accompanied by an emerging awareness of civil society where several countries (e.g., Indonesia, South Korea and Thailand) have embarked on societal governance in the wake of the 1997 Asia Financial Crisis (Zarsky & Tay, 2001). This increased awareness of environmental issues has encouraged the participation of a wider range of stakeholders in the areas of green production and management, including NGOs and consumers—the latter reported to be willing to pay more for products sourced from socially and environmentally responsible organizations (Marquis et al., 2015). These economic and societal transformations encourage organizations to integrate environmental management (EM) into their business models while presenting many new challenges.

Among the various tools organizations are mobilizing to proactively address environmental issues, green human resource management (GHRM) is increasingly seen as essential for the successful implementation of green strategies and EM practices (Daily & Huang, 2001; Renwick, Redman, & Maguire, 2008; Wehrmeyer, 1996). The concept of GHRM is evolving alongside the broader literature concerning sustainable development (Bunge, Cohen-Rosenthal, & Ruiz-Quintanilla, 1996; Howard-Grenville, Buckle, Hoskins, & George, 2014; Marcus & Fremeth, 2009) and has been established as a separate area of scholarship in the past decade (Jabbour & Santos, 2008; Jackson, Renwick, Jabbour, & Müller-Camen, 2011; Jackson & Seo, 2010; Renwick, Jabbour, Müller-Camen, Redman, & Wilkinson, 2016; Zoogah, 2011). Recent studies have linked GHRM to various aspects of EM and overall environmental performance in the Asia Pacific (e.g., Gholami, Rezaei, Saman, Sharif, & Zakuan, 2016; Li, Huang, Liu, & Cai, 2011; Paillé, Chen, Boiral, & Jin, 2014; O’Donohue & Torugsa, 2016; Subramanian, Abdulrahman, Wu, & Nath, 2016). Despite this recent surge in research, however, the theoretical foundations of GHRM, its measurement, the factors that constitute its source, and when and how it influences organizations’ outcomes remain largely undefined. The fast-growing yet still unclear nature of GHRM is not unique to Asia, but a common trend across the broader literature concerning GHRM. There is therefore an urgent need for a systematic and integrative assessment of the progress and potential in this emergent field of research.

Research on GHRM introduces ideas and issues that are only beginning to be studied by human resource management (HRM) scholars as they realize the strategic importance of EM in building sustainable organizations. For example, few HRM scholars have undertaken the task of using existing HRM models and theories to address the greening of an organization’s supply chains or product marketing, while GHRM research has established that GHRM should encompass these key management functions (Teixeira, Jabbour, Jabbour, Latan, & Oliveira, 2016). Aspects of the GHRM literature that can benefit from additional development include clarifying the conceptual relationship (including similarities and differences) between GHRM and other HRM specializations (such as sustainable HRM and high-performance work systems [HPWS]), addressing the difficult issue of how to measure GHRM, and giving serious consideration to the importance of context as a substantive issue (rather than treating context as merely an element of research design). By focusing research on these issues, GHRM scholars can reduce the risk of conflating the distinct antecedents, consequences, and contingencies of GHRM at individual and collective levels.

This paper seeks to advance the conceptual and empirical development of the GHRM field by providing a systematic and focused review of GHRM research. In contrast to the reviews provided by Renwick et al. (2008), Renwick, Redman, and Maguire (2013) and Tariq, Jan, and Ahmad (2016), this paper expands beyond a function-based perspective for understanding the possible linkages between specific HRM practices and EM. Focusing on the HRM practices used by organizations captures only a portion of the emerging and more expansive perspective of strategic HRM (Jackson, Schuler, & Jiang, 2014). Strategic HRM is partly distinguished by its inclusion of a wide range of stakeholders with differing concerns that may influence GHRM in the EM context (Wagner, 2011). The originality of this current review lies in: (1) an integrated approach to understanding the antecedents, contingencies, and outcomes of GHRM from the strategic HRM perspective, which in turn enables assessing the state of GHRM research vis-à-vis recent strategic HRM research advances (e.g., an employee-centric perspective and multi-level modeling); (2) a critical analysis of GHRM concerning its conceptualization, measurement, and theoretical basis; and (3) articulation of contextual factors that should be addressed in future GHRM research, including cultural influences that have been largely overlooked. This endeavor is important for two reasons. First, available knowledge in GHRM research is assessed, thus laying the foundations for the next stage of theoretical, methodological, and empirical advancement of the field. Second, research interest in deep contextualization (Tsui, 2007) is stimulated, encouraging future studies to work toward capturing and explaining the complexity, ambiguities, and uncertainties involved in GHRM across contexts.

To build a reliable knowledge base for a systematic review, we followed best practices as recommended in the literature (Short, 2009; Tranfield, Denyer, & Smart, 2003). Specifically, “green HRM,” “green human resource management,” “environment + HRM,” and “environment + human resource management” were used as search terms in the Business Source Complete, Expanded Academic ASAP, Science Direct, Academic One File, and Google Scholar databases to identify peer-reviewed English-language journal articles that made empirical or theoretical contributions, while excluding articles that provided prescriptive advice without supportive evidence. In the initial round of selection, only articles published in journals ranked “B” or above (based on the Australia ABDC Journal Quality List) were included, ensuring the inclusion of only high-quality papers. In the second round of selection, we included previously excluded journals with high impact factors for the subject matter. In total, 42 articles published between 2008 and 2017 were selected for inclusion in this review, of which 13 were conceptual and 29 empirical.

GHRM research demonstrates a number of new trends that warrant attention, but have not been addressed in previous studies (summarized in Table 1). First, while the majority of the existing literature addresses GHRM at the organizational level, a growing research stream focuses on green behavior and attitudes at the individual level. Second, while green training is the most frequently studied HRM practice, new forms of employment are gaining attention. Third, the literature reveals a shift from providing descriptive accounts of the prevalence or absence of GHRM practices to investigating antecedents, mediators, and moderators of the GHRM phenomenon. This shift suggests the imminent maturing of GHRM as a field of scholarly research.

This review and analysis of the emerging GHRM field are organized around four main issues. First, the conceptual foundations of GHRM are presented, tracing the origins and describing the dominant and emergent conceptualizations of the concept. Building on this, the ambiguity concerning how GHRM is perceived necessitates the development of a working definition for the concept. A discussion of the theoretical foundations of GHRM research is then undertaken, reviewing the available theoretical frameworks in the GHRM literature, especially as these relate to the latest theoretical advances in the broader HRM literature (namely, the consideration of employee behaviors and attitudes). The available measures for assessing GHRM are noted at the end of this section. Next, research that has examined the antecedents, consequences, and contingencies of GHRM is reviewed and presented as a conceptual framework for integrating existing research and guiding future studies. Finally, this review presents the prospects and challenges associated with GHRM research agendas and suggests several managerial implications.

Defining and measuring green human resource management

Origins and the core intuition

The concept of GHRM originated from the impetus for organizations to integrate sustainability into their internal activities and decision-making (Howard-Grenville et al., 2014; Marcus & Fremeth, 2009). The concept of sustainable development first entered common usage when outlined in the United Nations’ Brundtland Report (also known as Our Common Future), that defined it as “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” (World Commission on Environment and Development, 1987: 41). Sustainable development differs from traditional approaches to growth by simultaneously integrating considerations of economic development, social inclusion, and environmental protection (Connelly & Smith, 2012). In relation to these aspects of sustainable development, the natural environment is closely related to organizational activities in the sense that it constantly shapes, and is shaped by, the organizational environment (Dubois & Dubois, 2012). Correspondingly, the modern environmental movement, flourished in the 1960s and 1970s, exposed environmentally harmful human and organizational activities. As public awareness of and concerns about potential environmental damage gained momentum, they sparked the establishment of new institutions, stimulated new approaches to business management, and resulted in new advocacy activities across political, economic, and social domains (Bansal & Hunter, 2003; Buysse & Verbeke, 2003). This eventually resulted in a wide range of regulations aimed at reducing the environmental harm that had become a visible by-product of rapid economic growth and development.

In response to these changes, leading companies began promoting and implementing proactive EM practices and systems (Jabbour & Santos, 2008). Since their implementation, EM practices have seen technological innovation in waste reduction, energy conservation, and environmental preservation. To maximally leverage such practices and reap their benefits, however, requires organizations to adopt a systems perspective to orchestrate an array of practices, policies, procedures, and activities in the pursuit of EM goals (Marshall & Brown, 2003). Environmental considerations now influence a wide range of business activities, including green marketing (e.g., Ginsberg & Bloom, 2004), green operations (Simpson & Samson, 2008), and green accounting (e.g., Owen, 1992). Because people—company’s human resources—undertook the planning, coordination, and implementation of such green management activities (Daily & Huang, 2001; Renwick et al., 2008), GHRM naturally emerged as a concept in academic scholarship.

The core intuition guiding the emergence and development of GHRM is, as Wehrmeyer (1996) stated, “if a company is to adopt an environmentally-aware approach to its activities, the employees are the key to its success or failure” (7). This intuition shifts the strategies of EM from the macro-national level to the micro-foundations of a company and compliments the technical aspect of EM with the “human” aspects of the organization (Teixeira, Jabbour, & Jabbour, 2012). These “human” aspects are particularly important for EM because of the significant challenges that must be overcome as organizations strive to implement large-scale organizational change. As Dubois and Dubois (2012) observed, changes affected by the implementation of an EM system extend to all employees, not just those directly affected by new EM practices. Environmental issues also impact employees’ personal lives. Effective EM thus requires not only compliance with formal rules, but also employee engagement with and acceptance of voluntary initiatives.

Conceptualization

Despite the core intuition that human resources matter, the role of GHRM in an organization’s EM system remains ambiguous. The current conceptualizations of GHRM vis-à-vis EM is dominated by two schools of thought, which in turn influence the nature and focus of the research questions being addressed. As theorized by Taylor, Osland, and Egri (2012), HRM plays a dual role within environmental sustainability. First, HRM operates as a means to affect environment-driven changes and the GHRM concept is thus often treated as an HRM aspect of EM (Jabbour & Jabbour, 2016; Renwick et al., 2013). This is the de facto, leading conceptualization, based on early academic contributions linking the fields of EM and HRM (e.g., Wehrmeyer, 1996). Research that adopts this view focuses primarily on understanding the adoption and potential benefits of one or more specific HRM practices as organizations strive toward improving their environmental performance (e.g., Jabbour, Santos, & Nagano, 2010; Zibarras & Coan, 2015). Consequently, recruitment, performance management, training and development, and compensation are the most widely investigated HRM functions in the GHRM literature (Renwick et al., 2013).

The second school of thought expands the research domain by recognizing that GHRM also operates as an end to promote employee attitudinal and behavioral changes, improving the company’s environmental performance (Ehnert, 2009; Taylor et al., 2012). Following this line of thought, an emerging group of scholars have taken a broader view of GHRM to incorporate individual and collective capabilities that bring about green behavior, commitment, and motivation (Guerci, Montanari, Scapolan, & Epifanio, 2016b; Muster & Schrader, 2011; O’Donohue & Torugsa, 2016). Correspondingly, scholars have started to expand research focus beyond solely HRM functions and instead investigate broader employment characteristics relevant to achieving EM. For example, Consoli, Marin, Marzucchi, and Vona (2016) explored transformation in the organization of work tasks affected by EM implementation and found that green jobs used higher levels of cognitive and interpersonal skills more frequently compared to non-green jobs. The concept of green teams has emerged to describe teams that are formed (voluntarily or involuntarily) to solve organization’s environment-related problems or improve environmental performance (Jabbour, Santos, Fonseca, & Nagano, 2013). Additionally, Muster and Schrader (2011) argued that the previous research on EM and GHRM focuses only on working roles, underrepresenting the influence of employees’ private lives on their green behavior. Muster and Schrader consequently introduced the concept of green work-life balance and called for consideration of employees’ dual roles as both producers and consumers of green behavior.

Often implied in these conceptualizations of GHRM is recognition of the evolutionary stages that organizations experience as they move toward EM (Jabbour et al., 2010). When organizations progress from the reactive or preventive stages of EM to the proactive stages (Teixeira et al., 2012), GHRM shows an increased level of strategic value and affects greater integration of organizational and employee-centered human resource practices. The dual role of HRM within environmental sustainability (Taylor et al., 2012) suggests that GHRM and EM have a reciprocal relationship in which EM informs the greening of HRM, which in turn contributes to the long-term performance of EM (Wagner, 2011).

The conceptualization of GHRM thus involves not only traditional HRM functions that contribute to environmental goals, but also factors of employment and labor force that emerge or change as organizations adopt EM practices (Gholami et al., 2016). Yet despite the complexities involved in GHRM, there has been limited, if any, study that updates and consolidates the various schools of thought on the conceptualization of GHRM.

Working definition

Reflecting on the literature reviewed thus far, it is clear that the concept of GHRM requires a working definition that acknowledges the conventional emphasis on HRM functions while also recognizing the emergent focus on broader employment issues. An agreed definition of GHRM will advance this field of study and promote the development of theoretically sound arguments on the relationship between GHRM and EM. Indeed, Jackson and Seo (2010) voiced the concern that the lack of clear terminology, exacerbated by the intersection of strategic HRM and environmental sustainability, presents a barrier to define the scope of subsequent research. To address this terminology barrier, we propose a working definition of GHRM as phenomena relevant to understanding relationships between organizational activities that impact the natural environment and the design, evolution, implementation and influence of HRM systems. This definition adopts the meaning of an HRM system provided by Jackson et al. (2014: 3–4), and thus casts GHRM as an organization’s aspiration to design and implement an HRM system that supports a proactive and positive approach to addressing environmental concerns by (1) formulating an overarching HRM philosophy that reflects green values; (2) promulgating formal HRM policies that state the organization’s intent and serve to direct and partially constrain the green behavior of employees; (3) actively ensuring actual green HRM practice (by ensuring the daily enactment of green HRM philosophies and policies); and (4) using green technological processes for designing, implementing, evaluating, and modifying GHRM philosophies, policies, and practices as they evolve.

The aspect of this working definition of GHRM that distinguishes it from most definitions of sustainable HRM and strategic HRM is the explicit targeting of ecological concerns when describing the content of HRM. In contrast to the broader scope of sustainable HRM, which encompasses a simultaneous consideration of profit, planet, and people in the triple bottom line (Elkington, 2004) and has at times been used interchangeably with GHRM (Gholami et al., 2016), our working definition of GHRM focuses only on the ecological aspect of organizational activities (Boiral, 2009). This definition is supported by a growing body of research that shows the effectiveness of targeted HRM systems comprised of a set of strategically focused practices (e.g., as described by Jackson et al. [2014], those designed to manage knowledge-based teamwork, those that target customer service, or those designed to emphasize safety). Our definition rejects an assumption, implicit in most strategic HRM research, which assesses the presence of performance-enhancing HRM policies and practices (i.e., HPWS) without specifying the performance domains that are most relevant to specific strategic objectives.

Measurement

A lack of clear terminology has resulted in ambiguity regarding how to assess GHRM and what GHRM measures should encompass. For example, one approach has been to simply use (without modification) measures that were developed for strategic HRM research. This approach is illustrated by Paillé et al.’s (2014) adoption of the HPWS index developed by Huselid (1995) when investigating how HRM influences firms’ environmental performance. The advantage of this approach is its grounding in the vast literature showing that HPWS is associated with several generic indicators of firm performance.

In contrast, most GHRM scholars assume that a generic HPWS index is not sufficient if the goal is to leverage the HRM system to support EM initiatives and improve environmental performance. Instead, targeted HRM systems are more appropriate to achieve those objectives (for a discussion of other research employing targeted HRM systems, see Jackson et al. [2014]). Several studies have measured green-specific HRM practices using either qualitative analysis (e.g., Guerci & Carollo, 2016; Haddock-Millar, Sanyal, & Müller-Camen, 2016) or quantitative data (e.g., Pinzone, Guerci, Lettieri, & Redman, 2016). In these studies, the intent was to determine the extent to which a company’s HRM practices specifically incorporate ecological concerns. The advantage of this approach is that it focuses on HRM practices that clearly are intended to increase employee awareness, knowledge, skills, and motivations for the purpose of improving the company’s environmental performance. For example, Pinzone et al. (2016) measured GHRM by assessing performance management practices that incorporated environmental indicators and employee involvement practices that specifically addressed environmental issues. In another example of this approach, Antonioli, Mancinelli, and Mazzanti (2013) assessed three HRM practices that they believed would be relevant for firms pursuing ecological innovation: the percentage of employees covered by training programs, the extent to which training addressed several competencies that the authors believed would be relevant to improving environmental performance (technical, informatics, organizational, and economics/law), and the degree to which firms invested economic resources in training activities.

In a positive development for the field, work is underway to develop and validate more defensible measures of GHRM. Table 2 summarizes the available measures that specify ecologically relevant HRM policies and practices. For example, Jabbour et al. (2010) differentiated the functional and competitive dimensions of GHRM, which included six functional sub-dimensions (job description and analysis, recruitment, selection, training, performance appraisal, and reward system) and three competitive sub-dimensions (team, culture, and organizational learning). Zibarras and Coan (2015) constructed a GHRM measure with four dimensions (employee life cycle, rewards, education and training, and employee empowerment). Guerci, Longoni, and Luzzini (2016a) developed a GHRM measure to assess green hiring, green training, and involvement, and green performance management and compensation. O’Donohue and Torugsa (2016) measured GHRM with five items (environmental training, investment in people, creation of work-life balance and family-friendly employment, improved employee health and safety, and employee participation in decision-making processes). The approach used by these authors was dependent on them judging which HRM practices can potentially be used to support the organization’s environmental agenda, without clearly determining that those practices actually were designed to target environmental concerns.

Two relatively recent and comprehensive GHRM measures have been proposed by Gholami et al. (2016) and Tang, Chen, Jiang, Paillé, and Jia (2017), based on data collected in Malaysia and China respectively. Both measures include a wide array of HRM activities pertinent to GHRM. The lack of consensus around a clear definition of GHRM, however, means that the face validity of Gholami et al.’s (2016) measure can be challenged as more reflective of the general concept of strategic HRM or sustainable HRM (see Ehnert, 2009; Ehnert & Harry, 2012; Kramar, 2014) rather than specifically GHRM. In comparison, Tang et al.’s (2017) measure is more focused on ecologically relevant HRM practices, but its external validity beyond the Chinese context has not been determined.

As these previous studies illustrate, the early pioneers wishing to use a targeted measure of GHRM had to develop their own ad hoc measures and then argue for the face validity of their measurement choices. The applicability of these various indices is unclear to a broader research agenda aimed at systematically examining the effectiveness of GHRM practices across a wider variety of countries, industries, and types of organizations (Fernandez, Junquera, & Ordiz, 2003; Jabbour & Santos, 2008). For the field of GHRM to advance, research efforts must focus on developing psychometrically sound measures that assess clearly defined constructs.

Theoretical foundations

GHRM research remains largely devoid of theory. In articles explaining the guiding theoretical foundations, the assumption seems to be that “in the context of greener organizations, HRM tends to be transformed into GHRM” (Jabbour & Jabbour, 2016: 1825) in the strategic sense. While the strategic HRM literature has witnessed an array of theoretical perspectives (e.g., resource-based view, human capital theory, and the behavioral perspective), the GHRM research to date has mostly adopted the behavioral perspective (e.g., Jackson & Seo, 2010; Dubois & Dubois, 2012).

The behavioral perspective of strategic HRM was systematically adopted in Renwick et al.’s (2008) seminal review that argued that specific GHRM practices can shape the competencies, motivations, and opportunities available in the organization’s workforce. The abilities-motivation-opportunities model has since become the most widely used theoretical perspective for GHRM scholarship (e.g., Guerci et al., 2016a, 2016b; Pinzone et al., 2016). Studies in this area have identified and tested specific HRM practices for building employees’ green abilities (e.g., green competence building practices), increasing green motivation (e.g., green performance management practices), and providing green opportunities (e.g., green employee involvement practices). (For a more detailed discussion on this subject, see Renwick et al. [2013]).

Though seldom specified, the resource-based view lays a foundation for theorizing about the integration of GHRM (e.g., Antonioli et al., 2013) with other management functions (such as green supply chain management and product marketing) and is supported by an emerging research stream that takes a multidisciplinary approach to understanding green organizations (e.g., Jabbour & Jabbour, 2016). The synergistic integration of HRM with decisions on the coordination and structure of organizations’ operations (e.g., in supply chains and product marketing) can transform the human capital of individual employees into higher-order dynamic capabilities that are scarce, invaluable, inimitable, and non-substitutable.

Alternative theoretical foundations have also begun to take shape in the GHRM literature. For example, Zoogah (2011) integrated the cognitive social information processing perspective (Mischel & Shoda, 1995) and role behavior theory (Schuler & Jackson, 1987) to explain the contributions of GHRM in organizations’ achievement of environmental strategies. Stakeholder theory was used by Wehrmeyer (1996) in his pioneering work on HRM and EM. Stakeholder theory broadens the scope of GHRM research by moving beyond organizational boundaries to explore the consumer and regulatory stakeholder pressures that shape the diffusion of GHRM (Guerci et al., 2016a).

The value of using several alternative theoretical foundations lies in their potential to enrich the field of GHRM research. The theoretical fragmentation evident in the GHRM literature, however, presents a challenge to the formulation of an integrative framework to accommodate the wide range of new insights that are emerging.

A framework for understanding antecedents, consequences, and contingencies of GHRM

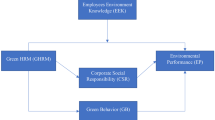

Beyond the foundational questions about the nature and conceptualization of GHRM, a considerable number of studies have attempted to explicate the antecedents, consequences and contingencies of GHRM, to which our discussion now turns. Figure 1 summarizes the overarching conceptual framework that guides our discussion.

Associated with the multiple theoretical approaches evident in the emerging GHRM literature are differences in the extent to which scholars address phenomena at different levels of analysis. Two levels of analysis are most prevalent in empirical studies of GHRM: employee (individual)-level phenomena and organization-level phenomena. Some studies have also incorporated group-level phenomena. A complete understanding of GHRM will likely require a multi-level approach that includes phenomena at several levels of analysis. With that in mind, we turn next to providing an overview of research that considers GHRM’s antecedents, outcomes, and associated contingencies.

Antecedents of GHRM

There are few studies that explicitly consider the antecedents of GHRM—the studies that do shed important light on the impact of the macro-level external environment, the organization-level environment, and the individual characteristics of employees.

The external environment

Three aspects of an organization’s external environment that may explain the emergence of GHRM systems are sources of pressure, sources of guidance, and sources of awareness, which often interact with each other to influence the design and effectiveness of GHRM. From an institutional theory perspective, increased monitoring of such pressures emanating from the external environment is likely to grow, primarily due to increased media attention, cultural values, and the development of civil society.

In the GHRM domain, national differences have been evident across diverse geographic locations, including the United States (US) (e.g., Haddock-Millar et al., 2016), Europe (e.g., Guerci & Carollo, 2016; Harvey, Williams, & Probert, 2013; Zibarras & Coan, 2015), Asia (e.g., Gholami et al., 2016; Subramanian et al., 2016), and South America (e.g., Jabbour et al., 2010; Teixeira et al., 2016). In addition to regulatory differences among countries, research has shown that Chinese, Indigenous Australians, Indians, and Thais differ among themselves in their views of nature and the environment, as well as from the views espoused in the US and Europe (Liu, Li, Zhu, Cai, & Wang, 2014; Selin, 2003; Sternfeld, 2015). Jackson et al. (2011) observed differences in the major drivers and impacts of environmental concerns on organizational activities between Germany, the United Kingdom (UK), and the US.

The national context encompasses many types of differences, including laws and regulations, cultural values, modes of economic development, and the state of civil society. In other words, numerous conditions corresponding to sources of guidance, pressure, and awareness can vary greatly between countries and regions. Regulatory environments may be moving toward convergence with the adoption of major treaties, such as the Paris Agreement that became effective in 2016 (United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, 2016) and the proliferation of widely adopted certification and reporting frameworks such as the ISO 14000 series of environmental standards (International Organization for Standardization, 2010). Nevertheless, even within the Asia Pacific region there are significant country-level differences in environmental laws, regulations, and governance. For example, despite implementing tougher regulations against environmentally harmful organizational activities, citizens’ right to a healthy environment was only written into the national constitutions of few Asian countries (Indonesia, Philippines, and South Korea) as of 2013 (Boyd, 2014). Another example is the power of regulations, in which China’s environmental protection law can be trumped by other legislations targeting specific national resources (e.g., water and agriculture), while Japan’s comprehensive basic environmental law is designed to avoid this situation (Zhang & Cao, 2015).

Using Asia as an example, it seems likely that cultural values in the region can be an enabling factor of GHRM. Confucianism and Daoism, philosophical traditions pervasive in much of East Asia, have long advocated harmony with nature (Ren, Wood, & Zhu, 2015). In China, worsening air pollution (especially smog, or wumai in Chinese) in recent years has sparked widespread speculation about the legitimacy of business from an ecological and moral perspective. China’s government is now promoting a nationwide campaign to build a harmonious society in China, resulting in key initiatives and measures in the latest (13th) Five-Year Plan (2016–2020), more transparent approaches to reporting and information flows (BBC, 2016), and legislative changes in 2014 to the Environmental Protection Law (Zhen, 2014).

Organization-level antecedents

Institutional contexts, both formal and informal, arguably have cascading effects on the internal environments of organizations, which comprise both organization- and employee-level antecedents to GHRM. Regarding organizational enablers of GHRM, Dubois and Dubois (2012) identified five elements that help to embed environmental sustainability in HRM design and implementation—leadership, strategy, organizational culture, structure, and reporting activities. These elements serve as proximal contextual cues to employees about the urgency, value, and necessity of GHRM. Additionally, research on corporate environmentalism also suggests the importance of organizational conditions as motivators of pro-environment initiatives like GHRM. Using stakeholder theory, Banerjee, Iyer, and Kashyap (2003) identified public concern, regulatory forces, competitive advantage, and top management commitment as antecedents of organizations’ internal environmental orientation. However, to date there is little evidence that these same forces help explain the development or adoption of GHRM policies and practices.

From the perspective of strategic management, environmental sustainability often is viewed as a cost that can harm profitability—undoubtedly one reason for the slow movement among companies to improve their environmental performance. An alternative view is that adopting environmentally sustainable management practices represents a strategic opportunity for firms that are responsive to changing external conditions; being responsive to changing conditions can be an effective way to increase demand for the firm’s products, avoid fines imposed by regulators, gain improved access to financial capital, and achieve a competitive advantage in the labor market (Ambec & Lanoie, 2012). Research conducted by the Center for Creative Leadership suggests that GHRM practices may be more prevalent in organizations where executives understand how conditions in the external environment create potential benefits for organizations that lead their industry in pursuing environmentally sustainable practices (van Velsor & Quinn, 2012).

A consideration of organization-level antecedents presents an opportunity to differentiate coercive management practices from those that support voluntary employee behaviors consistent with a firm’s environmental objectives. A review of the evidence to date suggests that an organization’s HRM policies and practices can influence both types of green employee behaviors (Norton, Parker, Zacher, & Ashkanasy, 2015), but the conditions that lead organizations to adopt one approach or the other are not yet understood (Renwick et al., 2016).

Employee-level antecedents

In addition to understanding the antecedents that explain when, why, and the degree to which a company shapes its HRM system to encourage eco-friendly behavior among its employees, several authors have suggested that a better understanding of individual differences in such behavior is needed. Studies investigating employee-level antecedents of eco-friendly behavior at work have identified several individual attributes that are predictive, including EM knowledge (Wiernik, Ones, & Dilchert, 2013), conscientiousness, and moral reflectiveness (Kim, Kim, Han, Jackson, & Ployhart, 2017), environmental experience (Andersson, Jackson, & Russell, 2013), and, to some degree, demographic characteristics such as gender, age, education, and income (Klein, D’Mello, & Wiernick, 2012). These individual characteristics may also enhance employees’ acceptance of GHRM. Alternatively, the extent to which an organization employs people with such characteristics may increase bottom-up pressures for the organization to respond to pressures emanating from the external environment by adopting elements of a GHRM system.

level-2 heading does not seem right. It is much smaller than the spacing after this paragraph and the next 3rd-level heading Outcomes of GHRM

Several studies have attempted to establish the effects of GHRM on outcomes of interest to employers. A review of the literature indicates that both green-specific and more general outcomes have been proposed as potential benefits of GHRM. Within each category, there are employee, team, and organizational levels of interest.

Organization-level outcomes

Designing and implementing GHRM requires major investments in organizational resources, likely leading managers to question whether such investments are worthwhile. That is, managers want answers to the “so what?” question: “Do organizations do well by doing good?” (Marquis et al., 2015).

Within the EM domain, Jabbour et al. (2010) demonstrated the contributions of specific GHRM dimensions to the evolutionary stages of EM. Teixeira et al. (2016) further developed the GHRM case specifically for other EM functions by demonstrating the positive influence of green training on the adoption of green supply chain practices (i.e., green purchasing and cooperation with customers). Additionally, Li et al. (2011) showed that green training has a direct and positive effect on firms’ performance in sustainable development for a sample of manufacturing firms in South and North China. They argued that training enhances a sense of business ethics and responsibility, which in turn helps improve EM performance. While these studies support GHRM as an element in the overall effectiveness of EM, the literature suggests that the links between GHRM, EM, and various forms of economic benefits are complex and require further theoretical and empirical development (Jabbour et al., 2010; Wagner, 2011).

Team-level outcomes

With the origin of GHRM in EM, the expectation is that human resources play a critical role in stimulating the success or failure of EM (Jabbour & Santos, 2008). For example, Jabbour (2011) argued that the lack of formalized GHRM is likely to have negative effects on team performance and organizational culture, creating a negative learning cycle and resulting in the ultimate failure of EM initiatives. Among the recent studies incorporating team- or collective-level phenomena, Pinzone et al. (2016) found that GHRM is positively associated with voluntary behaviors toward the environment at the collective level, mediated by collective affective commitment to EM change. While the empirical work linking GHRM to team-level outcomes is quite limited, it is reasonable to assume that HRM practices that influence the types of employees placed in leadership positions will also influence the green behaviors of other team members (see Kim et al., 2017). Organizations may be able to influence team-level ecological outcomes by selecting and/or developing team leaders who are inclined to behave in environmental responsible ways and thus serve as role models for other members of the team.

Employee-level outcomes

A core tenet of strategic HRM is aligning elements of HRM with the strategic goals and objectives of a firm, recognizing that employees are a valuable source of competitive advantage (Jiang, Lepak, Hu, & Baer, 2012). The employee-centric approach to understanding GHRM is thus an instantiation of strategic HRM that suggests effective GHRM provides opportunities for employees to contribute to the firm’s environmental performance, ensures employees have the abilities needed to perform effectively, and motivates employees to leverage the advantage of these opportunities and abilities to achieve eco-friendly performance outcomes. Thus, for example, Jackson and Seo (2010) called for research to understand employees’ performance of discretionary behaviors that can help organizations become greener. Subsequently, Paillé et al. (2014) were among the first to explicitly and empirically position their GHRM investigation as a study of employee organizational citizenship behavior directed toward environmental issues. Presumably, such behaviors would be associated with improved job performance for employees in relevant (green) jobs.

While the majority of speculation about GHRM outcomes concerns desirable effects such as improved environmental performance, an emerging stream of research links EM with a broader array of employee attitudes and behaviors beyond those specifically considered “green” and directly relevant to the environment (e.g., Bode, Singh, & Rogan, 2015). That is, in addition to outcomes that are the direct targets of GHRM, implementing GHRM may help to produce other generally desirable outcomes beyond those with ecological benefits. For example, a growing body of research suggests that organizations’ environmental activities are significantly related to employee satisfaction and retention (Wagner, 2011), and it is possible that such outcomes occur even in the absence of changes in employees’ green behaviors and their effects on EM.

The specific and more generalized effects of HRM systems have sometimes been referred to as the “hard” and “soft” results of HRM systems (Storey, 1989). Whereas the hard targets of GHRM include direct control of employee behaviors that are expected to affect environmental performance outcomes, the soft consequences of GHRM include improved employee attitudes toward their employing organization more generally.

Understanding the likely effects of GHRM on a wide array of employee attitudes and behaviors is of interest because employees often assume multiple roles simultaneously—recipients of the GHRM policies of a firm, implementers of GHRM practices, consumers in private life, and advocates and citizens who shape public policies. As Muster and Schrader (2011) observed, “environmentally relevant attitudes and behavior are not learned exclusively at the workplace, but also in private life” (141). Likewise, attitudes and behaviors shaped by the non-work sphere may carry over to influence work-related behaviors and attitudes. Practically, employee attitudes and behaviors toward the environment span both work and non-work domains, blurring the distinction between work and non-work outcomes.

Mediators and dynamic processes

In addition to considering both the green-specific and more general effects of GHRM, it is important to understand the relatively immediate short-term or proximal effects that help explain longer-term or more distal consequences. Following convention, Fig. 1 illustrates this distinction using the label “mediators” for proximal effects and/or the processes through which GHRM eventually can influence longer-term outcomes of interest to employers.

An improved understanding of the mediating processes through which GHRM influences green-specific and general outcomes is needed to guide the design of a GHRM system that can potentially achieve the intended longer-term outcomes. For example, a study of the civil aviation industry in the UK by Harvey et al. (2013) found that HRM policies and practices not only had a direct effect on green performance, but that the influence was mediated via employee attitudes such as commitment and engagement. Improved commitment and engagement may in turn encourage employee behaviors that are congruent with organization-level goals and strategies. Such self-regulatory mechanisms facilitate goal-setting and provide motivation for executing and sustaining goal-oriented efforts (Bandura, 1986).

Despite recent advances, research that provides insights into how employees respond to GHRM is in infancy. Even in organizations with a coherent GHRM system, variability in the perceptions, interpretation, and attributions of their employees (including line managers) are likely. Understanding how such micro-level processes shape employee green behavior is an important step in acquiring sufficient knowledge to create an effective GHRM system. Research in this area can build on the recent work of strategic HRM scholars who have examined the role of employee perceptions and interpretations of HRM practices (e.g., Bowen & Ostroff, 2004; Sanders & Yang, 2016; Wright & Nishii, 2007). A step in this direction was taken by Guerci and Pedrini (2014) in their discussion of managers’ cognitive mindsets concerning sustainable HRM in relation to environmental issues.

Implementing GHRM may elicit a chain of outcomes that benefit employers and employees alike in a variety of ways. Expanding the focus of GHRM research to include consideration of mediating processes as well as consideration of a wider range of outcomes is appropriate as embedding EM in an organization “sweeps across all levels of employees in all areas of an organization” and can have both organizational and personal consequences beyond simply complying with new rules (Dubois & Dubois, 2012: 801).

Contingencies of GHRM

Previously, we discussed how the emergence of GHRM is likely to depend on a variety of contextual conditions in the external and internal environments of organizations. Here we consider how contextual conditions as well as employee-level characteristics may shape or moderate relationships between GHRM and outcomes.

External environment

As previously stated, national differences in the adoption of GHRM is evident across geographic locations, and such differences are likely due to variation in the sources and amount of pressure emanating from external conditions. Such contextual differences may also shape relationships between GHRM and its antecedents as well as relationships between GHRM and its consequences.

The complex ways in which formal and informal institutional contexts combine to create unique and varied effects is illustrated by the findings of Liu et al.’s (2014) meta-analysis of 68 studies involving 71 samples. They found that proactive environmental strategies in Western countries are mostly strongly influenced by top managers’ mindsets and least influenced by regulations, while in China proactive environmental strategies are equally influenced by regulations, managerial mindsets, and stakeholder norms. It thus appears likely that the interplay between regulations, stakeholder pressures, and managerial characteristics has the potential to influence the adoption or extent to which GHRM produces the desired outcomes.

Internal environment

The effectiveness of GHRM practices may be contingent upon an organization’s internal context, which can shape both short-term and longer-term outcomes. For example, the availability of tangible (e.g., funds) and intangible (e.g., change management and learning capabilities) organizational resources may (1) enable organizations to access relevant information for efficient execution of green decisions; and (2) enable organizations to provide meaningful incentives and support to ensure employees execute and persist in green behaviors (Zibarras & Coan, 2015; Zoogah, 2011). Following this line of reasoning, organizational size appears to influence the extent to which environmental practices are implemented (e.g., Grant, Bergesen, & Jones, 2002; Wagner, 2011). While there are many possible explanations for the influence of organizational size, greater access to resources that can be used to improve the implementation of green initiatives is one potential benefit enjoyed by larger organizations.

In another example, Paillé et al. (2014) found that the degree to which top leaders were viewed as committed to protecting the environment positively moderated the effects of HRM practices on organizational citizenship behavior toward the environment. Although this study did not look specifically at organizations with GHRM systems, the findings were consistent with an emerging pattern of results in the strategic HRM literature that shows that formal HRM systems can work in synergistic combination with leadership styles or leaders and HRM systems can function as substitutes for each other (e.g., Chuang, Jackson, & Jiang, 2016; Hong, Liao, Raub, & Han, 2016). An improved understanding of the organizational conditions that increase the likelihood of positive outcomes from investing in GHRM will be especially useful for managers responsible for assessing the risks and rewards associated with such investments.

Research agenda

So far, as this review reveals, the emerging GHRM field is underdeveloped in the conceptual, theoretical and methodological domains of scholarly inquiry. As such, there are many opportunities for scholars to make significant contributions that advance this important field of investigation. Ideally, such research will build upon the foundations of related, more established fields of inquiry. In particular, we draw attention to building upon strategic HRM scholarship, which provides a strong foundation for developing studies that attend to the importance of taking context into account, recognizing the multi-level nature of organizational phenomena, and incorporating an employee-centric perspective. Next we discuss how incorporating these principles can promote a more comprehensive understanding of GHRM phenomena. Table 3 summarizes our central recommendations for advancing the GHRM research agenda.

Theoretical development

Conceptualization

Our review of the existing literature revealed a clear preference for conceptualizing GHRM as the HRM element of EM, but persistent confusion over how GHRM is similar to and distinct from other related concepts (including sustainable HRM and strategic HRM). Further, we observed differences in views concerning the question of whether to treat GHRM as an outcome that follows the adoption of an EM strategy or a means for achieving EM (see Guerci & Pedrini, 2014). Either perspective is likely to yield useful insights if the assumptions and theoretical arguments are clearly stated. To facilitate the advancement of GHRM scholarship, scholars must clearly state their conceptualization of GHRM and differentiate it from related terms. Such clarity in reports of original research will aid subsequent accumulation of knowledge and new theoretical analyses.

Similarly, future research should expand beyond the function-based approach to GHRM that has dominated most of the literature. By expanding GHRM conceptualizations to consider the broader, strategic significance of GHRM and recognizing its potential consequences for a wider range of outcomes beyond employees’ green behaviors and green performance, scholars may be more effective in building a conceptual foundation that adequately addresses the role of GHRM in contributing to the ability of organizations to satisfy their multiple, diverse stakeholders.

Theoretical perspectives

Studies of GHRM have generally adopted a strategic management perspective that emphasizes the economic considerations that drive organization’s decisions about how to invest resources. Increasingly, the behavioral perspective is being employed to explain how GHRM is likely to shape employees’ abilities, motivations, and opportunities.

While continued work that builds upon the foundational research grounded in the behavioral perspective and strategic HRM literature will be useful, following this path is not sufficient. We believe the GHRM literature is in urgent need of theoretical development that draws from a more diverse set of disciplines and philosophical foundations to provide a comprehensive and deep understanding of the phenomena. To paraphrase a Chinese saying, let a hundred flowers bloom, let a hundred schools of thought contend; there are several other theoretical perspectives that offer promising directions, such as institutional theory and the paradox of society in the sociology domain, and social cognitive theory and the theory of planned behavior in the psychology domain.

Specifically, sociological theories can help explain the complexity, ambiguity, and tension embedded in GHRM phenomena. Institutional theory could stimulate research that improves our understanding of the diffusion of GHRM systems across industries and countries (see Hoffman, 1999; Peng, 2002). Investigating the role of formal institutional transformation, coupled with changing social norms, on GHRM diffusion can address the issue of whether organizations should take a universal approach across contexts or employ an individualized approach to accommodate local contexts. The paradox-of-society perspective offers another promising avenue to uncovering paradoxes related to the implementation of GHRM systems vis-à-vis other management functions. For example, employing GHRM to improve environmental plans may increase the possibility of financial shortage and negatively impact other economic and social performances (Guerci & Carollo, 2016). Such paradoxical dynamics might suggest the potential for a curvilinear relationship between GHRM and economic and social performance. Alternatively, understanding such paradoxical dynamics might help organizations better anticipate the challenges they are likely to face as they attempt to implement and sustain GHRM efforts.

In addition, psychology theories such as social cognitive theory (Bandura, 1986) and the theory of planned behavior (e.g., Azjek, 2002) may help to improve our understanding of the dynamic processes through which GHRM influences employee attitudes and behaviors. A cognitive psychological lens allows in-depth analysis of whether a centralized department with personnel dedicated to GHRM produces better outcomes, or whether decentralized responsibilities for GHRM within all hierarchies are more conducive to elucidate pro-environmental employee behavior.

Employee perceptions and interpretations of GHRM

In recent years, some strategic HRM scholars have begun to examine the role of employees’ perceptions and interpretations of HRM practices as mediators in the HRM-performance relationship (Liao, Toya, Lepak, & Hong, 2009). GHRM researchers should take note this line of enquiry as it captures within-firm variations due to employee perceptions and interpretations of the “what” (HRM perception), “how” (HRM strength), and “why” (HRM attribution) of HRM practices (Bowen & Ostroff, 2004; Sanders & Yang, 2016). This employee-centric approach is relevant to GHRM as the effective management of environmental goals relies not only on compliance, but also on voluntary initiative, making employees’ cognitive and motivational processing of GHRM critical. Building upon the concept of HRM perceptions, future GHRM research might investigate how employee perceptions of GHRM practices align with other elements in a HRM system, and whether such alignment is essential for the effectiveness of the entire system. Building upon the concept of HRM strength, future research could also investigate the extent to which employees perceive GHRM practices as fostering a strong and persuasive situation leading to pro-environmental attitudes and behavior—the strength of GHRM systems potentially having both direct and moderating effects on employees’ attitudes and behavior. Building on the concept of HRM attribution, future research might investigate how employees understand and make sense of organizations’ motivations, as such attributions are likely to influence how employees respond to GHRM policies and practices.

Empirical research agenda

GHRM and other management functions

Although the GHRM concept reflects a strategic orientation to improving an organization’s environmental performance, the literature has not provided a comprehensive or adequate picture of the antecedents, dynamic processes, boundary conditions, and outcomes of GHRM. As shown in Fig. 1, the design and implementation of GHRM are likely influenced by numerous factors operating at multiple levels of analysis, from the most macro to the most micro. Further, due to the significant changes that are often required by organizations in the pursuit of improved environmental performance, research on GHRM presents opportunities for HRM scholars to address new types of research questions. For example, one opportunity for future research is to investigate the processes through which alignment of GHRM and other management functions can best be achieved; it is likely that the effectiveness of GHRM partly depends on how well the system used all of an organization’s functional areas to target environmental concerns. If other functional areas pursue environmental objectives—for example, using information technologies to track EM metrics and marketing initiatives for communicating green initiatives to external constituencies—without support from GHRM, the absence of GHRM is likely to be particularly problematic. Conversely, if an organization designs and adopts a comprehensive GHRM system but other functional areas do not also implement new management and operational practices, the effects of GHRM are likely to be minimal. Thus, for example, Bai and Chang’s (2015) study of Chinese companies with corporate social responsibility (CSR) practices in place found that such activities were linked to firm performance to the extent that firms also had marketing competence, which presumably ensured broad consumer awareness of the CSR activities.

Extending the domain for GHRM scholarship even further, scholars also have interesting opportunities to investigate the role of GHRM in facilitating effective inter-organizational arrangements, such as those required for effective supply chain management, successful integration following a merger or acquisition (e.g., Shi & Liao, 2013), management of international joint ventures (e.g., Chen & Wilson, 2003), and the flow of knowledge within multinational corporations, such as the transfer of knowledge from headquarters to regional facilities (e.g., Lunnan & Zhao, 2014). Embracing theoretical perspectives that view organizations as open systems rather than focusing on HRM as a functional specialty that can be studied in isolation would be a useful step in future studies.

Another research opportunity open to investigation is the relationship between GHRM and leadership. On this subject, the literature has indicated the importance of top leadership in supporting and promoting pro-environmental initiatives. However, more research is needed to (1) identify specific leadership styles and behaviors (e.g., responsible leadership, value-based leadership, and ethical leadership) that are relevant to effective GHRM; and (2) investigate how GHRM interacts with leadership at different levels (e.g., distributive leadership).

Measurement

Our review of empirical GHRM research suggests an urgent need to develop theoretically sound and empirically validated measures of GHRM to facilitate further research in this field. Organizations also need indicators that can help them determine their level of achievement in GHRM practices. We have noted that Gholami et al. (2016) and Tang et al. (2017) are at the forefront of developing such measures. Nonetheless, the extent to which their measures can be applied beyond the specific industries and countries in which the measures were developed still needs to be tested. Further, their measures were developed in firms that were already engaged in EM; whether it is appropriate and meaningful to apply these measures to firms in industries not closely related to green products needs further analysis.

Multi-level analysis

Multi-level approaches to understanding and studying GHRM at individual and collective levels (i.e., team and organization) are needed, given that “studying environmental issues is a truly multi-level phenomenon that involves individual-level processes such as advocacy … as well as more macro processes such as how states, regions, and even global processes affect organizational phenomena” (Marquis et al., 2015: 433–434). Research has only just begun to examine the relationship between GHRM and its antecedents/outcomes at different levels of analysis. More research is needed to understand the trickle-down and trickle-up effects of GHRM at the employee, team, and organizational levels. For example, existing research has empirically demonstrated that GHRM has a positive influence on collective green commitment and OCB (e.g., Pinzone et al., 2016). Future empirical work might seek to understand the effect on a wider range of employee attitudes and behaviors at both individual and collective levels. In addition, the degree to which GHRM is designed and implemented may vary across different business units within an organization. Researchers should thus investigate how GHRM at business-unit levels aggregates to the organizational level.

Another important research direction concerns cross-level effects of GHRM. Although GHRM can have a positive influence on collective outcomes, the effects on individual employees may be mixed. Even when collective outcomes are generally positive, understanding variations in outcomes at the individual level can be useful for diagnosing problems and making changes that contribute to continuous improvements in collective outcomes over time.

Context and contextualization

The lack of multi-level theorizing, to some extent, is associated with insufficient consideration of context. Typically, studies on GHRM treat industry and geographic context as elements to be considered when designing research and drawing conclusions from the results (e.g., Paillé et al., 2014), but rarely is the role of such contextual factors the subject of direct investigation. Institutional theory provides a basic guiding principle to identify institutional forces—external or internal, formal and informal—that constitute sources of pressure, guidance, and awareness that together give rise to GHRM. However, context is a multi-dimensional construct that encompasses not only geographic locations, but also economic, normative, technological, and legal dimensions that have not been investigated fully. The challenge of developing knowledge that respects contextual influences on the phenomenon of interest is important and not unique to GHRM research. Studies have proposed several ways to theorize context in the management field, including pursuing deep contextualization in context-embedded and context-specific research, discussing context explicitly, developing indigenous theories, and asking novel research questions (see Meyer, 2015; Tsui, 2004, 2007). We advocate two streams of research to build a more contextualized understanding of GHRM.

One stream of contextualized GHRM research could focus on understanding the conditions that support and enable the emergence and effective delivery of GHRM systems. Numerous conceptually relevant variations in context at the national, industrial, and organizational levels of analysis await empirical investigation. For example, although countries differ dramatically in terms of the specific environmental issues they face, GHRM literature has yet to consider whether, how, and why countries’ differences shape the contours and the specific elements of GHRM systems that develop in organizations. Likewise, industry type is known to influence how corporate environmentalism emerges (e.g., Banerjee et al., 2003). The manufacturing sector is the most frequently discussed sector in environmental training studies (Jabbour, 2011), but environmental issues must also be addressed by firms in the service sector. Further studies are needed to examine the service sector and/or to compare different sectors.

A second stream of research focused on context is needed to improve our understanding of how national cultures influence the meaning and thus the consequences of GHRM systems. Our review of existing literature found no research examining how culture influences the effects of GHRM, although there is an implicit understanding that environmental issues differ across cultures (Liu et al., 2014; Selin, 2003; Sternfeld, 2015). Understanding countries’ differences as direct influences on GHRM and as moderators that shape the adoption and effectiveness of GHRM is especially important as environmental issues increasingly require transnational collaboration. The combination of international environmental agreements and regulations and the growth of supply chains that increasingly engage firms across multiple countries are likely to result in GHRM systems being transferred and applied across countries by multinational enterprises.

Methodology

Understanding the contribution of GHRM to the bottom line is important as “businesses will not necessarily introduce green management practices because of the normative obligation, but because green management coincides with their economic interest to satisfy key stakeholders and thrive as profitable enterprises” (Marcus & Fremeth, 2009: 19). A challenge to establishing a strategic case for GHRM is that its effects take time and are likely to fluctuate due to changes in the organization or the business environment. Researchers should therefore take a dynamic perspective in future studies and collect data from multiple sources on performance outcomes over several time periods in a greater time frame.

Implications for practice

Our review has focused on scholarly inquiry into GHRM. A number of practical implications can nevertheless be drawn from our organizing framework for review (i.e., Fig. 1). First, to foster GHRM, our framework suggests that organizations need to pay attention to both organization-initiated changes related to EM and employee perceptions and interpretations of GHRM. For example, organizations could invest in employee engagement surveys to understand how their employees perceive the alignment between GHRM practices and “best HRM practices.” Organizations could also encourage information flow to understand how employees perceive the environmentally focused messages that GHRM conveys. Additionally, organizations could foster green work-life balance to align the compliance expectations in the work domain with employee attitudes toward the environment in their private domain.

Second, given that every organization faces resource constraints, it is advised that GHRM systems include the objective of encouraging employee-driven initiatives. Boiral and Paillé (2012) identified three types of discretionary employee behaviors directed toward the natural environment: eco-initiatives, eco-helping, and eco-civic. Their findings suggest that such organizational citizenship behaviors can be directed outside the work domain in the form of personal initiatives—toward other people in the workplace in the form of mutual support and toward the organization in the form of support for the organization’s commitments.

Third, considering the scholarly debate about the role of GHRM in the HRM department and the role of GHRM professionals in the organization, it is also advisable for organizations to embed GHRM practices and responsibilities across all levels within the organization. This can be achieved, for example, by incorporating GHRM goals and practices into the information management system where the factors relevant to the development (i.e., antecedents) and delivery (i.e., mediators and moderators) of GHRM are mapped into workforce planning and performance evaluation respectively.

Finally, managers may find that they can use the available GHRM scales (i.e., Table 2) in several ways. For example, such scales could be used to assess and compare the relative extent and degree of GHRM practices in different units of the organization, to compare GHRM across partners in the supply chain, to benchmark one’s organization against other organizations, or to monitor changes over time within the organization.

Conclusion

This review has synthesized scholarly inquiry into GHRM since Renwick et al. (2008) presented the seminal review work that laid the foundation for the recent GHRM research. The first objective of the review—conceptually linking various treatments of the GHRM concept to its origins and evolution—reveals an urgent need to provide clarity to the concept of GHRM, and thereby supports the development of a systematic and valid GHRM instrument that has cross-cultural validity. The second objective of this review—evaluating theoretical perspectives—proved more difficult. Owing to the relatively young age of GHRM as a field, there is not yet sufficient variety in the theoretical perspectives utilized to assess which are likely to prove most useful for future development. Strategic HRM seems to be the dominant meta-theory for the foundation of GHRM, yet the field of strategic HRM itself has been criticized as lacking theoretical depth and sophistication (e.g., Guest, 1997, 2011). However, this weakness creates various opportunities for innovative and important research in the GHRM field. Our third objective for this review—integrating empirical evidence that explains GHRM-related phenomena—reveals a fast-growing GHRM literature with many issues still unanswered. Our proposed framework highlights and organizes several likely antecedents, consequences, and contingencies of GHRM and positions GHRM systems within an organization’s wider management context. With the continued awareness of environmental sustainability, GHRM is now clearly a legitimate field of academic pursuit. It has the potential to offer new insights into transformation of the forms and means of management, employment, and organizing not only in Asia, but across the world.

References

Ambec, S., & Lanoie, P. 2012. The strategic importance of environmental sustainability. In S. E. Jackson, D. S. Ones, & S. Dilchert (Eds.). Managing human resources for environmental sustainability: 21–35. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Andersson, L., Jackson, S. E., & Russell, S. V. 2013. Greening organizational behavior: An introduction to the special issue. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 34(2): 151–155.

Angel, D. P., & Rock, M. T. (Eds.) 2000. Asia’s clean revolution: Industry, growth and the environment. Sheffield: Greenleaf.

Antonioli, D., Mancinelli, S., & Mazzanti, M. 2013. Is environmental innovation embedded within high-performance organisational changes? The role of human resource management and complementarity in green business strategies. Research Policy, 42: 975–988.

APEC. 2016. APEC cuts environmental goods tariff. http://www.apec.org/Press/News-Releases/2016/0128_EG.aspx, Accessed Dec. 1, 2016.

Azjek, I. 2002. Perceived behavioral control, self-efficacy, locus of control, and the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 32(4): 665–683.

Bai, X., & Chang, J. 2015. Corporate social responsibility and firm performance: The mediating role of marketing competence and the moderating role of market environment. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 32(2): 505–530.

Bandura, A. 1986. Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory, 1st ed. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

Banerjee, S. B., Iyer, E. S., & Kashyap, R. K. 2003. Corporate environmentalism: Antecedents and influence of industry type. Journal of Marketing, 67(2): 106–122.

Bansal, P., & Hunter, T. 2003. Strategic explanations for the early adoption of ISO 14001. Journal of Business Ethics, 46(3): 289–299.

Bode, C., Singh, J., & Rogan, M. 2015. Corporate social initiatives and employee retention. Organization Science, 26(6): 1702–1720.

Boiral, O. 2009. Greening the corporation through organizational citizenship behaviors. Journal of Business Ethics, 87(2): 221–236.

Boiral, O., & Paillé, P. 2012. Organizational citizenship behaviour for the environment: Measurement and validation. Journal of Business Ethics, 109(4): 431–445.

Bowen, D. E., & Ostroff, C. 2004. Understanding HRM–firm performance linkages: The role of the “strength” of the HRM system. Academy of Management Review, 29(2): 203–221.

Boyd, D. R. 2014. The status of constitutional protection for the environment in other nations. David Suzuki Foundation.

Bunge, J., Cohen-Rosenthal, E., & Ruiz-Quintanilla, A. 1996. Employee participation in pollution reduction: Preliminary analysis of the Toxics Release Inventory. Journal of Cleaner Production, 4(1): 9–16.

Buysse, K., & Verbeke, A. 2003. Proactive environmental strategies: Stakeholder management perspective. Strategic Management Journal, 24(5): 453–470.

Chen, S., & Wilson, M. 2003. Standardization and localization of human resource management in Sino-foreign joint ventures. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 20(3): 397–408.

Chuang, C.-H., Jackson, S. E., & Jiang, Y. 2016. Can knowledge-intensive teamwork be managed? Examining the roles of HRM systems, leadership, and tacit knowledge. Journal of Management, 42: 524–554.

Connelly, J., & Smith, G. 2012. Politics and the environment: From theory to practice. Hoboken: Taylor and Francis.

Consoli, D., Marin, G., Marzucchi, A., & Vona, F. 2016. Do green jobs differ from non-green jobs in terms of skills and human capital?. Research Policy, 45: 1046–1060.

Daily, B. F., & Huang, S. 2001. Achieving sustainability through attention to human resource factors in environmental management. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 21: 1539–1552.

Dubois, C. L. Z., & Dubois, D. A. 2012. Strategic HRM as social design for environmental sustainability in organization. Human Resource Management, 51(3): 799–826.

Ehnert, I. 2009. Sustainable human resource management: A conceptual and exploratory analysis from a paradox perspective. Berlin: Physica-Verlag.

Ehnert, I., & Harry, W. 2012. Recent developments and future prospects on sustainable human resource management: Introduction to the Special Issue. Management Revue, 23(3): 221–238.

Elkington, J. 2004. Enter the triple bottom line. In A. Henriques, & J. Richardson (Eds.). The triple bottom line, does it all add up? Assessing the sustainability of business and CSR: 1–16. London: Earthscan.

Fernandez, E., Junquera, B., & Ordiz, M. 2003. Organizational culture and human resources in the environmental issue. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 14(4): 634–656.

Gholami, H., Rezaei, G., Saman, M. Z. M., Sharif, S., & Zakuan, N. 2016. State-of-the-art green HRM system: Sustainability in the sports center in Malaysia using a multi-methods approach and opportunities for future research. Journal of Cleaner Production, 124: 142–163.

Ginsberg, J. M., & Bloom, P. N. 2004. Choosing the right green marketing strategy. MIT Sloan Management Review, 46(1): 79–84.

Grant, D. S., Bergesen, A. J., & Jones, A. W. 2002. Organizational size and pollution: The case of the U.S. chemical industry. American Sociological Review, 67(3): 389–407.

Guerci, M., & Carollo, L. 2016. A paradox view on green human resource management: Insights from the Italian context. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 27(2): 212–238.

Guerci, M., & Pedrini, M. 2014. The consensus between Italian HR and sustainability managers on HR management for sustainability-driven change - towards a 'strong' HR management system. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 25(13): 1787–1814.

Guest, D. E. 1997. Human resource management and performance: A review and research agenda. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 8(3): 263–276.

Guest, D. E. 2011. Human resource management and performance: Still searching for some answers. Human Resource Management Journal, 21(1): 3–13.

Haddock-Millar, J., Sanyal, C., & Müller-Camen, M. 2016. Green human resource management: A comparative qualitative case study of a United States multinational corporation. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 27(2): 192–211.

Harvey, G., Williams, K., & Probert, J. 2013. Greening the airline pilot: HRM and the green performance of airlines in the UK. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 24(1): 152–166.

Hoffman, A. J. 1999. Institutional evolution and change: Environmentalism and the US chemical industry. Academy of Management Journal, 42(4): 351–371.

Hong, Y., Liao, H., Raub, S., & Han, J. H. 2016. What it takes to get proactive: An integrative multilevel model of the antecedents of personal initiative. Journal of Applied Psychology, 101: 687–701.