Abstract

Legislators (i.e., elected Senators and House Representatives at the federal- and state-level) are a critically important dissemination audience because they shape the architecture of the US mental health system through budgetary and regulatory decisions. In this Point of View, we argue that legislators are a neglected audience in mental health dissemination research. We synthesize relevant research, discuss its potential implications for dissemination efforts, identify challenges, and outline areas for future study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Writing about the importance of translational science in 2009, Tom Insel (then Director of the National Institute of Mental Health [NIMH]) stated that “Both scientific and political efforts will be required to ensure that the fruits of research are disseminated efficiently to those who most need it” (Insel 2009). Since then, increased investments have been made in scientific efforts to help ensure that evidence reaches mental health clinicians and influences care. This is demonstrated in part by NIMH’s funding of 40 projects through Dissemination and Implementation Research in Health Program Announcements between 2007 and 2014—27 % of all projects funded through these announcements (Purtle et al. 2016b). But what about political efforts and activities to ensure that mental health evidence reaches legislators and does not get lost in the politics of policymaking? In this Point of View, we argue that legislators are a neglected audience in mental health dissemination research. We synthesize relevant research, discuss its potential implications for dissemination efforts, identify challenges, and outline areas for future study.

The Importance of Legislators

Legislators (i.e., elected Senators and House Representatives at the federal- and state-level) are a critically important dissemination audience because they shape the architecture of the US mental health system through budgetary and regulatory decisions. There are 7918 legislators in the United States—535 at the federal-level and 7383 at the state-level—and each has potential to affect the population-level determinants of mental health through the votes they cast and the legislation they introduce. For example, studies show that the success of efforts to increase access to evidence-based mental health services is dependent upon supportive legislation (e.g., parity laws that ensure insurance coverage, loan repayment programs that address workforce shortages) (Raghavan et al. 2008). Research has also identified how legislation can address the social determinants of mental health by preventing exposure to toxic stressors and providing buffering resources (Allen et al. 2014; Sederer 2015; Shern et al. 2016; Thoits 2010). In order for this knowledge inform legislative decisions, however, it must reach and be used by legislators.

Despite the importance of legislators as a dissemination audience, systematic reviews demonstrate that barely any empiric studies have investigated how mental health evidence can be most effectively disseminated to them (Goldner et al. 2011; Oliver et al. 2014; Purtle et al. 2016b; Williamson et al. 2015). These reviews do indicate, however, that disseminating research evidence to legislators is complicated because they are particularly susceptible to the politics of public opinion and have distinct information needs (Bogenschneider and Corbett 2011). Translating mental health research into legislation requires dissemination strategies that account for these complexities.

Policy Dissemination Research

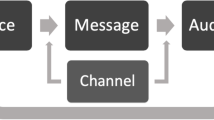

Policy dissemination research—defined as the study of how, why, and under what circumstances scientific evidence is used by policymakers—offers potential to inform the design of these strategies (Purtle et al. 2016b). A transdisciplinary endeavor, policy dissemination research uses theories, concepts, and methods from disciplines such political science, communication, and implementation science to understand political contexts and develop dissemination strategies that are tailored to reflect them. Although policy dissemination research has primarily focused on physical health (Dodson et al. 2012), a synthesis of relevant research yields four themes that have implications for disseminating mental health evidence to legislators.

Four Themes from Research

The first three themes come from public opinion research on mental illness. Public opinion research elucidates the political context in which research evidence is interpreted by legislators and can thus inform how to effectively disseminate it (Corrigan and Watson 2003). The first theme is that notions of mental illness and inter-personal violence are intertwined in the minds of the US public. Americans implicate a failed mental health system as a primary reason for inter-personal violence and focusing events (e.g. mass shootings) sometimes spark political will for legislators to address mental illness (Barry et al. 2013; Metzl and MacLeish 2015; Saad 2013). Mass shooting might be an opportune time to disseminate evidence to legislators and correct the misconception that all people with mental illness are at increased risk for inter-personal violence perpetration (Swanson et al. 2015).

Second, many Americans hold stigmatizing attitudes towards people with mental illness (Parcesepe and Cabassa 2013; Stuber et al. 2014); and these attitudes are inversely correlated with public support for mental health legislation (Barry and McGinty 2014; Corrigan and Watson 2003; Corrigan et al. 2004; McSween 2002). For example, Barry and McGinty (2014) found that US adults who held stigmatizing attitudes towards people with mental illness were 29 % less likely to support mental health parity laws and 24 % less likely to support increased government spending on mental health services.

Because public support influences legislators’ decisions, the effectiveness of legislator-focused research dissemination strategies might be maximized if implemented in conjunction with communication campaigns that reduce stigma among legislators and their constituents (Raghavan et al. 2008). Contact strategies, in which members of a stigmatized population (i.e., people with mental illness) meet and develop relationships with the general population, are also a relevant stigma reduction approach (Corrigan et al. 2012; Couture and Penn 2003).

Third, while Americans believe that mental illnesses adversely affect quality of life, they are less willing to pay for them than physical health conditions. In one study, US adults rated depression as being 19 % more burdensome than an amputated limb but were willing to pay 27 % less to prevent depression than amputation (Smith et al. 2012). Another study found that Americans were less supportive of requirements for insurance providers to cover mental health services than all other medical services (Maust et al. 2015). These findings suggest that messaging that emphasizes the social, in addition to the financial, costs of mental illness might be needed to foster support for spending on mental health legislation. Narrative dissemination techniques that utilize stories about people affected by an issue have demonstrated effectiveness at cultivating legislator support for physical health interventions and could also be effective at communicating mental health evidence to legislators (Brownson et al. 2011; Stamatakis et al. 2010).

Fourth, and finally, policy studies shed light on the sources from which legislators acquire research evidence. Studies of US state legislators have found that seeking research evidence from internal legislative staff is the practice legislators engage in most frequently, while contacting researchers directly and reading/watching media coverage is engaged in least frequently (Bogenschneider and Corbett 2011; Dodson et al. 2015; Purtle et al. 2016a). These findings suggest that mental health researchers should consider establishing relationships with, and disseminating research findings directly to, legislative staff.

Future Research

These four themes provide guidance about how mental health research might be effectively disseminated to legislative audiences, but do not obviate the need for future study. Formative assessments of legislators’ knowledge and attitudes about mental illness, similar to surveys conducted with the general public, are a critical first step to designing dissemination strategies which address knowledge deficits and correct misconceptions. These studies should examine nuances between legislators with different characteristics (e.g., federal vs. state, Democrat vs. Republican) so that dissemination activities can be tailored accordingly. There is also a need for studies that capture how mental health research evidence is, and is not, used in legislative processes. Qualitative case studies that utilize key informant interviews, document reviews, and media analysis offer an approach (Waddell et al. 2005).

Studies are also needed to determine the comparative effectiveness of different dissemination strategies on legislator support for evidence-supported mental health legislation. Randomized designs that test the comparative effectiveness of different dissemination materials (e.g., data-focused vs. narrative-focused policy briefs) on support for mental health legislation, introduction of legislation, and subsequent voting behavior are possible approaches.

Challenges

Policy dissemination research holds potential for bridging the gap between what mental health researchers know and what legislators do, but is not a panacea. Even if abundant knowledge existed about how to most effectively disseminate mental health evidence to legislators, many challenges would remain. After evidence reaches legislators, there is the risk of it being coopted and used to support pre-determined political positions (Haynes et al. 2011; Weiss 1979). For example, US state legislators have identified ‘using research to justify a decision’ as one of the most common uses of evidence (Purtle et al. 2016a).

Furthermore, policy dissemination research might inform how mental health research evidence can be effectively disseminated to legislators, but does not typically address who should do the disseminating. Researchers at academic institutions are generally not incentivized to engage in policy-focused dissemination activities. The strategies identified above (e.g., establishing relationships with legislative staff, rapidly disseminating research finding when focusing events occur) require time investments from researchers. Although policy dissemination activities may be considered “service” in academic settings, they are unlikely to substantially contribute to career development and influence promotion and tenure decisions (Brownson et al. 2006). Barriers also stem from the fact that many researchers feel uncomfortable engaging in legislative processes (Grande et al. 2014; Otten et al. 2015) and are uncertain about how to effectively do so (Trupin and Kerns 2015; Trupin et al. 1989).

Conclusions

The barriers to translating mental health research into legislation are formidable, but not insurmountable. As with other challenges facing the field of mental health research, these barriers can be overcome, or at least diminished, through systematic study. Policy dissemination research can help achieve this and should be a more prominent focus of translational science in mental health. Politics will never be taken out of the legislative process, but scientific evidence can be more effectively infused into it.

References

Allen, J., Balfour, R., Bell, R., & Marmot, M. (2014). Social determinants of mental health. International Review of Psychiatry, 26(4), 392–407.

Barry, C. L., & McGinty, E. E. (2014). Stigma and public support for parity and government spending on mental health: a 2013 National Opinion Survey. Psychiatric Services, 65(10), 1265–1268.

Barry, C. L., McGinty, E. E., Vernick, J. S., & Webster, D. W. (2013). After Newtown—public opinion on gun policy and mental illness. New England Journal of Medicine, 368(12), 1077–1081.

Bogenschneider, K., & Corbett, T. J. (2011). Evidence-based policymaking: Insights from policy-minded researchers and research-minded policymakers. New York: Routledge.

Brownson, R. C., Dodson, E. A., Stamatakis, K. A., Casey, C. M., Elliott, M. B., Luke, D. A., et al. (2011). Communicating evidence-based information on cancer prevention to state-level policy makers. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. doi:10.1093/jnci/djq529.

Brownson, R. C., Royer, C., Ewing, R., & McBride, T. D. (2006). Researchers and policymakers: travelers in parallel universes. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 30(2), 164–172.

Corrigan, P. W., Morris, S. B., Michaels, P. J., Rafacz, J. D., & Rüsch, N. (2012). Challenging the public stigma of mental illness: a meta-analysis of outcome studies. Psychiatric Services, 63(10), 963–973.

Corrigan, P. W., & Watson, A. C. (2003). Factors that explain how policy makers distribute resources to mental health services. Psychiatric Services, 54(4), 501–507.

Corrigan, P. W., Watson, A. C., Warpinski, A. C., & Gracia, G. (2004). Stigmatizing attitudes about mental illness and allocation of resources to mental health services. Community Mental Health Journal, 40(4), 297–307.

Couture, S., & Penn, D. (2003). Interpersonal contact and the stigma of mental illness: a review of the literature. Journal of Mental Health, 12(3), 291–305.

Dodson, E., Brownson, R. C., & Weiss, S. (2012). Policy dissemination research. In R. C. Brownson, G. A. Colditz, & E. K. Proctor (Eds.), Dissemination and implementation research in health: Translating science to practice. Oxford: Oxford University Press

Dodson, E. A., Geary, N. A., & Brownson, R. C. (2015). State legislators’ sources and use of information: bridging the gap between research and policy. Health Education Research, 30(6), 840–848. doi:10.1093/her/cyv044.

Goldner, E. M., Jeffries, V., Bilsker, D., Jenkins, E., Menear, M., & Petermann, L. (2011). Knowledge translation in mental health: a scoping review. Healthcare Policy, 7(2), 83.

Grande, D., Gollust, S. E., Pany, M., Seymour, J., Goss, A., Kilaru, A., et al. (2014). Translating research for health policy: researchers’ perceptions and use of social media. Health Affairs. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0300.

Haynes, A. S., Gillespie, J. A., Derrick, G. E., Hall, W. D., Redman, S., Chapman, S., et al. (2011). Galvanizers, guides, champions, and shields: the many ways that policymakers use public health researchers. Milbank Quarterly, 89(4), 564–598.

Insel, T. R. (2009). Translating scientific opportunity into public health impact: a strategic plan for research on mental illness. Archives of General Psychiatry, 66(2), 128–133.

Maust, D. T., Moniz, M. H., Zivin, K., Kales, H. C., & Davis, M. M. (2015). Attitudes about required coverage of mental health care in a US national sample. Psychiatric Services, 66(10), 1101–1104. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.201400387.

McSween, J. L. (2002). The role of group interest, identity, and stigma in determining mental health policy preferences. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law, 27(5), 773–800.

Metzl, J. M., & MacLeish, K. T. (2015). Mental illness, mass shootings, and the politics of American firearms. American Journal of Public Health, 105(2), 240–249.

Oliver, K., Innvar, S., Lorenc, T., Woodman, J., & Thomas, J. (2014). A systematic review of barriers to and facilitators of the use of evidence by policymakers. BMC Health Services Research, 14(1), 1.

Otten, J. J., Dodson, E. A., Fleischhacker, S., Siddiqi, S., & Quinn, E. L. (2015). Peer Reviewed: Getting Research to the Policy Table: A Qualitative Study With Public Health Researchers on Engaging With Policy Makers. Preventing Chronic Disease, 12, E56. doi:10.5888/pcd12.140546.

Parcesepe, A. M., & Cabassa, L. J. (2013). Public stigma of mental illness in the United States: a systematic literature review. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 40(5), 384–399.

Purtle, J., Dodson, E. A., & Brownson, R. C. (2016a). Uses of research evidence by State legislators who prioritize behavioral health issues. Psychiatric Services. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.201500443.

Purtle, J., Peters, R., & Brownson, R. C. (2016b). A review of policy dissemination and implementation research funded by the National Institutes of Health, 2007–2014. Implementation Science, 11(1), 1.

Raghavan, R., Bright, C. L., & Shadoin, A. L. (2008). Toward a policy ecology of implementation of evidence-based practices in public mental health settings. Implementation Science, 3(26), 3–26.

Saad, L. (2013). Americans Fault Mental Health System Most for Gun Violence: Gallup. http://www.gallup.com/poll/164507/americans-fault-mental-health-system-gun-violence.aspx. Accessed 11 July 2016.

Sederer, L. I. (2015). The social determinants of mental health. Psychiatric Services, 67(2), 234–235.

Shern, D. L., Blanch, A. K., & Steverman, S. M. (2016). Toxic stress, behavioral health, and the next major era in public health. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 86(2), 109–123. doi:10.1037/ort0000120.

Smith, D. M., Damschroder, L. J., Kim, S. Y., & Ubel, P. A. (2012). What’s it worth? Public willingness to pay to avoid mental illnesses compared with general medical illnesses. Psychiatric Services, 63(4), 319–324. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.201000036.

Stamatakis, K. A., McBride, T. D., & Brownson, R. C. (2010). Communicating prevention messages to policy makers: the role of stories in promoting physical activity. Journal of Physical Activity & Health, 7(01), S99.

Stuber, J. P., Rocha, A., Christian, A., & Link, B. G. (2014). Conceptions of mental illness: attitudes of mental health professionals and the general public. Psychiatric Services, 65(4), 490–497.

Swanson, J. W., McGinty, E. E., Fazel, S., & Mays, V. M. (2015). Mental illness and reduction of gun violence and suicide: bringing epidemiologic research to policy. Annals of Epidemiology, 25(5), 366–376.

Thoits, P. A. (2010). Stress and health major findings and policy implications. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 51(1 suppl), S41–S53.

Trupin, E., & Kerns, S. (2015). Introduction to the special issue: legislation related to children’s evidence-based practice. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 1–5. doi:10.1007/s10488-015-0666-5.

Trupin, E., McDermott, J., & Forsyth-Stephens, A. (1989). Maximizing the role of state legislatures in the development of mental health policy. Hospital & Community Psychiatry, 40, 637–638.

Waddell, C., Lavis, J. N., Abelson, J., Lomas, J., Shepherd, C. A., Bird-Gayson, T., et al. (2005). Research use in children’s mental health policy in Canada: maintaining vigilance amid ambiguity. Social Science and Medicine, 61(8), 1649–1657.

Weiss, C. H. (1979). The many meanings of research utilization. Public Administration Review, 39(5), 426–431.

Williamson, A., Makkar, S. R., McGrath, C., & Redman, S. (2015). How can the use of evidence in mental health policy be increased? A Systematic Review. Psychiatric Services, 66(8), 783–797. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.201400329.

Author Contribution

JP conceptualized the manuscript and led the writing. RB and EP contributed to the conceptualization of the manuscript, reviewed, and revised drafts and revisions. All authors approved and are accountable for all aspects of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

None of the authors have any conflicts of interest to disclose.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Purtle, J., Brownson, R.C. & Proctor, E.K. Infusing Science into Politics and Policy: The Importance of Legislators as an Audience in Mental Health Policy Dissemination Research. Adm Policy Ment Health 44, 160–163 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-016-0752-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-016-0752-3