Abstract

It has been suggested that user involvement in heath care leads to improved services. The aim of the study was to explore attitudes towards user involvement of staff employed in Norwegian Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS). Most of the investigated mental health service staff expressed the opinion that users should be involved in the planning of their own treatment and generally have a positive attitude towards user involvement. Skepticism was related to some aspects of involvement and does not contradict their generally positive attitude towards user involvement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

It is now well accepted that a patient’s active participation in treatment is necessary for a speedy and successful recovery from disease or surgery (Brody et al. 1989; Kristensson-Hallström et al. 1997; Grace et al. 2002; Kaba and Sooriakumaran 2007). However, the precise nature of user involvement is the subject of considerable discussion and the requirement of active participation is particularly challenging in child and adolescent mental health services (CAMHS), where usually active participation will include the child or adolescent and his/her carer.

A number of arguments in favor of user involvement have been suggested, including that involvement will: (1) lead to improved health services and that this will, in turn, improve clinical outcomes; (2) lead to a more effective utilization of available resources; and (3) reduce the frequency of discrimination. The active and direct involvement of users in their own treatment increases the feeling of personal responsibility for changes in the course of treatment and can lead to better therapeutic outcomes including increased self-esteem and coping potential (Delsignore et al. 2008; Kent and Read 1998, citing Farina and Fisher 1982; Garber and Seligman 1980; Greenfield et al. 1985; Schwarzer 1992; Nelson and Borkovec 1989; Lefley 1990; Soffe et al. 2004). Sometimes just the opportunity to talk, combined with the experience of being heard, can be a relief for users (Lewis 2004). One explanation for this anticipated benefit is provided by the framework of internal versus external locus of control originally developed by Rotter (1966). More involvement could lead to an increased internal locus of control, implying more perceived control over the users’ behavior, which is assumed to correspond to better health and a quicker recovery than an external locus of control (Griffiths and Jordan 1998; Nyland et al. 2002).

Fully involved users may be more likely to follow through with their treatment. Users have direct experience of what works in treatment and of what is demanding or even unhelpful (Bryant 2008). Furthermore, stimulating discussion and debate with the users on treatment alternatives can challenge the often observed dependency of users on mental health services, a dependency fostered by long-term involvement with the service (see examples given by Worrall-Davies 2008). When users or former users (usually parents in the case of CAMHs) are employed in case management by mental health services there is some evidence that users with whom they worked have fewer hospital admissions and some improved quality of life (Simpson and House 2002, 2003; Chinman et al. 2001; Felton et al. 1995). User coworkers usually spent longer in face-to-face contact with their clients, did more outreach work, had a higher turn-over rate and had fewer distinct professional boundaries than mental health professionals (Simpson and House 2002). In the case of users actively involved in teaching processes, the experience of being heard and respected as an individual by students is assumed to contribute to their recovery (Tew et al. 2003).

Much has been written about possible barriers and obstacles to user involvement in mental health services (Telford and Faulkner 2004). For example, some users and carers have no interest in being involved and feel a sense of inadequacy regarding the possibility of involvement, whilst many others do not perceive themselves as being asked to become involved (Kent and Read 1998; Soffe et al. 2004). Moreover, both staff and users have expressed concerns that users lack the necessary ability and experience to participate effectively and that the burden of involvement and the related role strain could be too stressful for users (Simpson and House 2003). While staff have questioned the representativeness of involved users (Tait and Lester 2005), there is some evidence from one UK study that the views of user groups’ members were representative of those held by ordinary patients (Crawford and Rutter 2004). On the other hand, tokenistic involvement (for example in only trivial tasks or in the very late stages of the development of services or policies, with the resulting very limited input possibilities) have led to mistrust and reluctance to become involved on the part of users (Simpson and House 2002, 2003; Middelton et al. 2004).

Additional complicating conditions can be seen in the unequal power relationship between medical staff and service users, underscored by the doctors’ legal responsibility for the treatment provided and their legal duty to enforce detention. The unequal relationship is reinforced by the different language mental health professionals use, which may result in a communication barrier, the stigma that is still associated with suffering from a serious mental illness or using mental health services, and the complexities of the mental health care system itself. This inequality is underscored by the fact that user involvement does not really derive from a free choice—at no point did the patient elect to suffer mental health problems, the primary eligibility criterion.

With regard to CAMHS, parents’ uncertainty about whether or not problems experienced by their child should be classified as a mental health problem and, consequently, whether they should seek help from CAMHS, has sometimes been reported as an initial problem (Collins et al. 2004). Moreover, the nature of user involvement in CAMHS is complicated by the duality of users: the minor and his/her parent/guardian. Minors are aware of their own likes and dislikes and adolescents usually have great concerns about privacy, wanting to be actively involved in the development of their treatment plan and to make informed decisions regarding their care (Worrall-Davies 2008; Worrall-Davies and Marino-Francis 2008). This desire for independence may conflict with the carers’ expectations that they will be involved in key decisions regarding persons they care for and be continuously informed about their treatment.

Indeed the involvement of carers may be particularly problematic in relation to the treatment of children, especially adolescents. The autonomy of the mature minor to make his/her decisions about medical treatment for which she/he has the relevant capacity is recognized by the law and has considerable political support. However, the involvement of carers in such cases may in fact reverse that situation, leading to the disempowerment of adolescents as the importance of their carers’ views are stressed by user involvement policies. It should also be noted that the interests of carers and children may not be synonymous and that, in treating minors, clinicians should insure that they act in the interests of the user, rather than those of the perhaps more vocal carer. An additional complication arises when carers disagree with each other about the best way to proceed.

Thus, while there is a general consensus on the importance of user involvement in decisions about their own treatment (Barley et al. 2007), there is no shared understanding of user involvement per se and no agreement as to the appropriate nature and extent of user involvement. Moreover, there is little knowledge of both how the majority of users themselves wish to be involved and of staff attitudes towards various forms of user involvement (Barley et al. 2007; Worrall-Davies and Marino-Francis 2008). The effects of involving users in mental health services have not been thoroughly investigated, particularly in relation to CAMHS (Worrall-Davies and Marino-Francis 2008; Worrall-Davies 2008).

Moreover, an important prerequisite of effective user involvement is the establishment of training programs for service users and staff members in order to ensure meaningful and realistic user involvement in service provision (Barley et al. 2007; Kent and Read 1998; Tait and Lester 2005).

User Involvement in Norwegian Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services

Over the past 20 years several parents’ initiatives and user organizations have developed into powerful, accepted and respected voluntary groups and organizations that are active both at the national and local levels, for example “Mental Health (Youth)”, ADHD Association and “Adults for Children”. The Norwegian government has explicitly recognized the importance of providing these organizations with financial support, making this a priority, and several of these organizations enjoy considerable political support. Thus, for example, user involvement in CAMHS is mandated and formulated as a particular task by the government’s strategic plan for child and adolescent mental health: ‘Together for mental health’ (Regeringens strategiplan for barn og unges psykiske helse 2003), based on a comprehensive, multilevel, segmented state health care system. The high priority attached to increased user involvement in Norway is evident in the health laws of January 2001 which emphasize user involvement and Regulation 676 which sets out every client’s right to an “individual care plan” (Regulations 676 2001). Moreover, all mental health care control commissions are required to appoint at least one member representing the interests of users and a patients’ ombudsman has been created.

Despite comprehensive political campaigns regarding user involvement, the implementation of user involvement technologies and user satisfaction studies, there is a dearth of data about attitudes of CAMHS staff towards user involvement, the expectations of CAMHS staff, and possible positive or negative outcomes of user involvement both for users and CAMHS staff. However, it is clear that before user involvement can function at a strategic level, the starting point must be the individual level of interaction between the user and the mental health professional (Tait and Lester 2005). Thus, understanding attitudes of CAMHS staff towards user involvement is critical.

The aims of this investigation were to:

-

a.

Explore Norwegian CAMHS staff attitudes towards user involvement (mandated by the government’s strategic plan for the development of Norwegian CAMHS.) This follows from the suggestion of Soffe et al. (2004) and Kent and Read (1998) who found a dearth of research on mental health professionals’ attitudes. This lack of research is particularly true in the CAMHS setting where no data is available.

-

b.

Investigate relationships between staff attitudes towards user involvement in CAMHS and selected professional and work related background factors.

-

c.

Compare the findings with results from investigations in New Zealand (Kent and Read 1998) and the UK in adult mental health service staff (Soffe et al. 2004). A detailed literature search did not yield any investigation of the Consumer Participation Questionnaire (CPQ) or any other measurement of staff attitudes in CAMHS (Kent and Read 1998) or by any other measurement. Therefore, we compared our findings with studies from the adult mental health service arena.

Methods

Sample and Procedure

This cross-sectional survey was carried out by the Regional Centre for Child and Adolescent Mental Health, Regions East and South Norway, in Oslo. One member of the board of the Norwegian parents’ association of ADHD children was included in the project group. The regional committee of ethics in health (psychology) research approved the project.

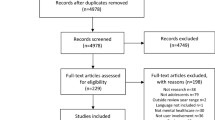

Twenty-four CAMHS institutes were randomly selected from all of the districts in two of the five Norwegian health care regions (east and south), which include Norway’s capital Oslo (14 specialized CAMHS centres, 4 state child protection institutes, and 6 community CAMHS centres). The leaders of these institutes were contacted by phone, the aims of the investigation were explained, and the leaders were asked to participate in the study. In order to obtain the required number of questionnaires, the eligible leaders provided the number of staff within their institution, operationally defined as staff with direct contact with users who enter journal notes. None of the leaders refused to participate and the number of requested questionnaires varied between 3 and 75. A total of 455 questionnaires were distributed together with a letter containing a description of the study. Two hundred thirty-two questionnaires were returned, of which 192 had been completed and were included in the data analysis, yielding a response rate of about 42%. Questionnaires were returned blank because the staff members thought that the questions did not apply to their workplace. The survey was anonymous and voluntary. Consequently, no reminders could be sent for non-returns.

The average age of the subjects was 42.4 ± 9.7 years (range 26–68); most of the subjects were female (75%); psychologists (29%); working at a specialized CAMHS centre (88%), but not in a leading position (82%) (Table 1).

Measures

The Consumer Participation Questionnaire (CPQ) (Kent and Read 1998), “specifically designed … to survey the opinions and perceptions of mental health professionals.” (p. 298), was translated into Norwegian according to established guidelines including backtranslation (Brislin 1976; Sartorius and Kuyken 1994); modified for use by Norwegian CAMHS staff; and applied in a pilot test. In addition to the fact that there were few measures available in this area, this questionnaire was chosen because it was developed in consultation with experienced users of mental health services.

The original CPQ consists of 20 items with 14 items referring to ‘Yes’, ‘No’, or ‘Don’t know’ response categories; 4 referring to a 5-point Likert type scale; and 2 items provide 6 or 8 specific options (Soffe et al. 2004; Kent and Read 1998). “In order to obtain information on consumer involvement at all levels of service delivery items were designed to cover treatment, evaluation, planning, and management. Items surrounding professionals’ beliefs and attitudes towards the issue of responsibility for various aspects of treatment were also included, as were questions which elicited opinions about consumers themselves and the possible outcomes that might result from increased consumer participation” (Kent and Read 1998) (p. 299).

In order to adapt the questionnaire to Norwegian CAMHS conditions the following changes were made:

-

the term ‘consumer’ was changed to ‘child/adolescent and his/her family’.

-

the original item 2, relating to the user-friendliness of complaints procedures, was split into two parts—one with the focus upon the parents (item 2aN in Table 2)) and a second focusing upon the children (item 2bN in Table 2).

Table 2 Items of the Consumer Participation Questionnaire—Percentages of the Norwegian investigation/New Zealand/UK -

about 3 new items were created and inserted as items 6–8 (item 6: ‘Do you inform clients about actual treatment methods?’—‘Yes’, ‘No’, ‘Don’t know’; item 7: ‘In most cases, where does the responsibility for deciding the type of therapy usually lie?’—see item 9; Table 2; item 8: ‘Do you use a treatment contract?’—‘Yes, verbal agreement’, ‘Yes, written plan’, ‘Yes, form based individual plan’, ‘No’).

-

a space for free comments was inserted after every item.

Statistical Analysis

Percentages are reported on each item. Chi-square tests have been calculated for testing for differences between the study data and the data taken from the literature (Kent and Read 1998; Soffe et al. 2004) as well as for testing for relationships between CPQ items and background variables and for interrelationships between the CPQ items. The comparison with the New Zealand data is based on the whole sample, but the comparison with the UK data is only based on the data from the Norwegian clinical psychologists working in CAMHS since the UK data is composed of psychologists.

Only significant findings are presented; relationships between background variables of the subjects and ‘Don’t know’ answers and missing values have been separately analyzed when their frequency exceeded or was equal to 10%.

Results

Structure of the CPQ

Because of the variation in the response model of the items, we analyzed relationships between the items by means of chi-square tests and only results with significance of <.01 are reported because of multiple testing. The theoretically assumed structure with the four major topics, treatment, evaluation, planning, and management, is not consistently reflected by the data (Appendix 1). The items representing the treatment topic almost always closely correlated with each other and were independent of items relating to other topics.

Findings in the Norwegian CAMHS Sample Based on the CPQ (Kent and Read 1998)

Treatment

Records and Service User Rights (items 3, 4, 13 and 15)

The vast majority of the Norwegian CAMHS staff believes that the users are “told they have a right to see their records”; and that they are informed about “confidentiality and privacy regarding the information contained in those records”. However, only about a quarter of the subjects expressed the opinion that the users should “contribute to the writing of their notes and records”, whilst one-fifth answered ‘Don’t know’. Exactly half of the respondents indicated that their service “sponsor[s] events/forums that educate service users about their rights and entitlements” and most of the remaining respondents were unsure about that question (‘Don’t know’ 43%). Social workers and pedagogic staff members denied the users’ “right to see their records” more often than members of the other professions (each with about 80%—χ 2 (8) = 23.76; p = 0.022); whereas doctors (80%) and psychologists (62%) stated that users should not “contribute to the writing of their notes and records” more often and nurses (48%) stated that users should contribute to such records more often than members of other professions (χ 2 (8) = 9.55; p = 0.004). More social workers and psychologists (about 20% of each group) than members of the other professions did not know their opinion about the involvement of users in writing-up their records. Only non-specialists stated that they did not know about users’ “right[s] to see their records” and 80% of those who said that the users were not told about these rights were non-specialist staff members (χ 2 = 10.25; Fisher’s exact test p = 0.005). Co-workers from community agencies stated that the users are not informed “of the facts about confidentiality and privacy” more often than those from specialized services (17 vs. 4%—χ 2 = 11.67; Fisher’s exact p = 0.040). Specialists reported that their service sponsored user education events more often than non-specialists and less often that they did not know about that (63 vs. 42%/28 vs. 51%—χ 2 = 8.49; Fisher’s exact test p = 0.014). Leaders reported that their service sponsored such events more often than junior staff members and answered do not know less often (10 vs. 47%—χ 2 = 15.70; Fisher’s exact test p < 0.001).

Assessment Procedure (item 14)

82% of the surveyed CAMHS staff stated that users should always or usually “be involved in the evaluation and diagnosis of their presenting problem(s)”. Employees at specialized services believed that users should always “be involved in the evaluation and diagnosis of their presenting problem(s)” more often than those in community services (63 vs. 42%) and indicated less often that they did not know (28 vs. 51—χ 2 = 8.49; Fisher’s exact test p = 0.014).

Planning of Treatment (items 6N, 7N, 8N, 6, 7 and 16)

Almost all of the investigated mental health service staff expressed the opinion that users should “be involved in the planning of their own treatment”. Most of the respondents thought that users and staff share “the responsibility for deciding the goals of treatment” equally (40%), whereas other respondents thought that in most cases that responsibility lies mostly with the CAMHS worker or with the user (25, 26% respectively). However, “the responsibility for deciding the type of therapy” was largely seen as the preserve of service staff with little responsibility for the user (61%), with less than a quarter of subjects expressing a preference for sharing this responsibility equally with the user. Nearly all surveyed staff indicated that they inform users “about actual treatment methods”; and almost all use an individual treatment contract (95%), albeit with a quarter of them just in a verbal form (25%). Non-specialists more often responded that users are not informed “about actual treatment methods” (11 vs. 3%—χ 2 = 6.49; Fisher’s exact test p = 0.034).

Evaluation

Complaint Procedure (items 1 and 2.aN, 2.bN)

Half of the surveyed CAMHS staff members stated that their service has “a complaints procedure for service users” (49%), but one-third did not know (32%). About 50% of the physicians, 40% of the psychologists and pedagogic staff, about 40% of those working in a junior position, and about a third of those working at a specialized service centre, did not know whether or not their agency has “a complaints procedure”. A little more than a third believed that this procedure is “in plain language” and the “procedures [are] user-friendly” for adults (37%), whereas only 15% believed this in relation to children. About a third of the psychologists, a fifth of the pedagogic staff members and about 40% of junior staff were unable to decide whether or not the complaints procedure is easy to navigate for the users (items 2. aN, bN 50, 56% respectively). One-third of the female respondents (34 vs. 22% of males), about 40% of the physicians, social workers and pedagogical staff members, 30% of the psychologists, 42% of staff in a junior position and 45% of those working in community services did not answer these questions (average 30%). Leaders of CAMHS reported that their service has “a complaints procedure” more often than junior staff (70 vs. 45%—χ 2 = 9.55; Fisher’s exact test p = 0.004) and that it is easy to follow for children (about 1/3 vs. 2/3—χ 2 = 7.27; Fisher’s exact test p = 0.017), whereas more junior staff did not know (22 vs. 3%). With regard to the profession of the respondents, nurses and pedagogic staff members reported that they think that their service has “a complaints procedure for service users” more often than the other professions (68, 50% respectively—χ 2 (8) = 25.58; p = 0.012); social workers and nurses more often perceived the procedure as accessible to adults (52, 55% respectively—χ 2 (8) = 24.22; p = 0.019).

Satisfaction Surveys (item 9)

About a quarter of the respondents believed that their service “routinely conduct[s] service user satisfaction surveys” (26%), whereas about one-fifth did not know (average 19%—about 20% of the physicians, psychologists and pedagogical staff, together with 22% of the junior staff members vs. 3% of leaders). Nurses, psychologists and pedagogical staff reported that there were no routine “user satisfaction surveys” in their agency more often than members of other professions (>90, 77, 51% respectively—χ 2 (8) = 8.91; p = 0.012). Junior staff stated more often than leaders of CAMHS that there were no (77 vs. 51%) routine “user satisfaction surveys” (χ 2 (2) = 8.91; p = 0.012).

Planning

Consumer Input (items 5 and 8)

The vast majority of the surveyed staff members reported that they had “heard of or read anything about user involvement”; and just under half of them believe that their “service solicit[s] user input for the planning of the mental health services”, whilst one-fifth answered do not know. More leaders than junior CAMHS members stated that their “service solicit[ed] user input for the planning of the mental health services” (61 vs. 31%); whereas more junior staff did not know (23 vs. 7%—χ 2 = 9.13; Fisher’s exact test p = 0.010).

Predicted Outcome of Consumer Involvement (items 18 and 20)

It was assumed by the majority of the staff (79%) that the involvement of users “in the planning and/or delivery of” CAHMS could improve the service provided to some extent, with most of them rating such involvement as likely to lead to an improvement (53%), but about one-fifth did not know (19%). Staff believed that users could benefit from involvement more “the first time round” (63%); that “services and delivery” could be upgraded (58%), and that “the ‘revolving door’ syndrome” could be reduced (43%) if “users were involved in service planning and/or delivery”. However, only 12% of staff believed that such involvement would effect a decrease in their own “burnout and stress” levels and 10% (primarily made up of pedagogic staff members with about 23% and juniors—23%—vs. leaders—7%) did not respond to this item. Specialists believed that the involvement of “users in service planning and/or delivery” will upgrade the service more often than non-specialists (69 vs. 53%—χ 2 = 4.28; Fisher’s exact test p = 0.048), and that this would cause “less burnout and stress” for the service providers (21 vs. 8%—χ 2 = 6.17; Fisher’s exact test p = 0.022).

Management

Staff Appointments (item 10)

The vast majority stated that users are not “involved in the hiring decisions” of service staff, the rest did not know.

Training (items 11 and 12)

Users seem to be “invited to participate in staff training meetings” in CAMHS centres in only a few cases (15%); about one-fifth of respondents stated that their service had asked users “to act as teachers at staff training events” at least once (21%), but a quarter of the respondents did not know (26%). Users were more often asked “to act as teachers at staff training events” by specialized service centres than by community services (22 vs. 5%—χ 2 = 8.45; Fisher’s exact test p = 0.0038).

Employment of Consumers (item 17)

About one quarter of the surveyed staff members believed there would be some improvement in their CAMHS; whereas about two-third preferred not to express their own opinion about probable changes in CAMHS if “users were employed by that service” (‘Don’t know’ category). Amongst those who did not respond to item 17 (10%) more belonged to the social work and pedagogic staff (each about 24%) than to the other professions; there were substantially more non-specialists (85%) and more junior staff (53%). Nurses (50%) anticipated a big improvement of the CAMHS if service users were employed more often than members of the other professions, whereas 25% of the doctors and 35% of the pedagogic staff members stated that they did not know more often than the social workers (7%—χ 2 (16) = 36.60; p = 0.048; average 19%).

Possible Reasons for Non-involvement (item 19)

The respondents believed that the main reasons for users decisions not to be involved in CAMHS would be: (a) “lack of trust in the ability of the services to provide help”; (b) “lacking in self-confidence”, (c) “too vulnerable”; and (d) “not wanting to have any further contact after getting better” with a missing value rate of 12%.

Differences Between New Zealand Adult Mental Health Service Workers (Kent and Read 1998) and Norwegian CAMHS workers

The New Zealand sample consisted of a mixture of various professions. Therefore, we compared the reported findings to those in the total Norwegian sample. The New Zealand sample was much smaller (72 vs. 192 subjects in Norway) and their response rate of 20% was substantially lower than that of the Norwegian study population (42%).

Treatment

The Norwegian CAMHS workers indicated that their service sponsored user education events more often, or that they did not know, than the New Zealand adult mental health workers (item 13: χ 2 (6) = 88.47; p < 0.001). Moreover, the Norwegian subjects responded that users should always “be involved in the evaluation and diagnosis of their presenting problem(s)” more often than the New Zealand subjects (χ 2 (6) = 38.17; p < 0.001). However, the Norwegians expressed the opinion that users or carers should “contribute to the writings of their notes and records” less often than the New Zealanders and chose the response ‘Don’t know’ more often (χ 2 (6) = 30.44; p < 0.001).

Evaluation

The respondents in New Zealand stated that their “service [has] a complaints procedure for service users” and that it is “simple to use” substantially more often than the Norwegian respondents and they indicated less often that they did not know (item 1: χ 2 (6) = 30.33; p < 0.001; item 2. aN: χ 2 (6) = 16.03; p < 0.010).

Planning

Norwegian staff members stated that their “service solicit[ed] service user input for the planning of mental health service” less often than the New Zealand staff and more often answered do not know (χ 2 (6) = 20,50; p = 0.001). Despite insignificant distribution-differences on the answer-categories related to the question, the effect of service user involvement in service “planning and/or delivery”, Norwegians indicated that this would cause an “upgrading of services and delivery” (58 vs. 20%), would yield a greater “chance that service users would benefit from those services the first time round” (63 vs. 25%); and “less chance of the ‘revolving door’ syndrome” (43 vs. 16%) much more often than their New Zealand counterparts.

Management

New Zealand mental health workers reported that service users are “involved in the hiring decisions of [their] service’s staff” more often than their Norwegian CAMHS colleagues and more often that they did not know (χ 2 (6) = 38.20; p < 0.001). On average the Norwegian staff members were less likely to believe that there would be an improvement in mental health services if “users were employed by that service”, or reported more often that they did not know, compared to New Zealand staff (χ 2 (12) = 22.44; p = 0.010). Even though there was no significant difference between the countries in relation to the distribution of the indicated possible reasons for a user’s decision not “to be involved in mental health services”, the Norwegians believed that the users experience a “lack of trust in the ability of the services to provide help” much more often than the New Zealanders (52 vs. 15%) who most often believed that the users are “lacking in self-confidence” (23 vs. 25%).

Differences Between UK Psychologists in Adult Mental Health Service (Soffe et al. 2004) and Norwegian CAMHS Psychologists

The UK sample consisted of 26 psychologists representing a response rate of 52%. The sub-sample of Norwegian psychologists working in CAMHS consisted of 54 individuals representing an assumed response rate of 42% when accepting the hypothesis that the response rate in the Norwegian sample was similar in all professions.

Treatment

Norwegian psychologists stated that “service users [are] told they have a right to see their records” more often than their UK colleagues in adult mental health (χ 2 (6) = 33.65; p < 0.001); and that their service “sponsor[s] events/forums that educate service users about their rights and entitlements” (χ 2 (6) = 32.25; p < 0.001). However they responded less often than the UK psychologists that the users should “contribute to the writing of their notes and records” (χ 2 (6) = 13.98; p = 0.022). Furthermore, Norwegian psychologists stated that, in most cases, “the responsibility for deciding the goals of treatment” should usually lie with the user more often than the UK subjects thought (χ 2 (6) = 13.98; p = 0.022); and that users should “be involved in the evaluation and diagnosis of their presenting problem(s)” (χ 2 (6) = 76.54; p < 0.001).

Evaluation

In common with the comparison with the New Zealand sample, the UK psychologists stated that their service has “a complaints procedure for the service users” and that these procedures are “simple to use” substantially more often than the Norwegian psychologists and they indicated less often that they did know (item 1: χ 2 (6) = 65.72; p < 0.001; item 2. aN: χ 2 (6) = 12.74; p = 0.025).

Planning

More Norwegian psychologists indicated that they had “heard of or read anything about service user involvement” than those from the UK (χ 2 (6) = 15.34; p = 0.010). The assumed impact of service user involvement in service “planning and/or delivery” are very much alike for the psychologists from both countries except for the fact that the UK psychologists believed “that service users would only be regarded as tokens by the professionals” substantially more often (36 vs. 8%).

Management

More psychologists from the UK thought that users were involved in “hiring decisions of [their] service’s staff” than Norwegian CAMHS psychologists (χ 2 (6) = 18.24; p = 0.004); and the Norwegian subjects believed there would be less improvement in the CAMHS if users “were employed by [their] service” than their UK colleagues (χ 2 (12) = 44.57; p < 0.001). On the level of the single answer category, the UK psychologist more often believed that “the main reasons service users might not choose to be involved in mental health services” were “not wanting to have any further contact after getting better” (65 vs. 21%); “lacking in self-confidence” (52 vs. 17%), and “lacking in motivation” (44 vs. 17%); whereas the Norwegian psychologists believed that “lack of trust in the ability of the services to provide help” would more often be the reason for his/her decision (62 vs. 47%) (no substantial difference in the distribution of answers).

Discussion

Our findings suggest that the majority of Norwegian CAMHS employees have a positive attitude towards user involvement in CAMHS; that they are better informed about what user involvement could mean compared to colleagues in other countries; and that they have heard or read about this topic more often than colleagues from the UK or New Zealand, although it should be noted that the New Zealand investigation was carried out about 10 years ago. The Norwegian CAMHS co-workers, particularly doctors and psychologists, seem to meet their information duties related to users’ rights, treatment goals and treatment alternatives, including the use of treatment contracts, to a higher degree than their colleagues in adult mental health services abroad. However, CAMHS staff responses suggest less enthusiasm, at least as reported for user involvement in treatment decisions and writing their notes, something that is practiced more often by their colleagues in New Zealand and the UK in adult mental health services. This attitude is further expressed in the belief of the majority of the surveyed Norwegian staff that user involvement in planning and/or delivery would improve the service just a little and that staff would not benefit from such policies. Taken together these responses imply a somewhat more skeptical and possibly negative attitude towards some types of user involvement (Katan and Prager 1986).

Conversely, the Norwegian CAMHS employees seem to have a more collaborative approach to evaluation and diagnosis than their New Zealand and UK colleagues. According to the those surveyed, it is highly important that complaints procedures be established which are easy to understand and accomplish both for parents and minors, a mechanism that seems to be more developed in New Zealand and the UK. Users are reported to rarely be invited to staff training meetings and to adopt a teaching role in staff training. The availability of user satisfaction surveys seems to be less common in Norwegian CAMHS and they are routinely used less often than in New Zealand and UK.

To the best of our knowledge, our investigation represents the first empirical study of CAMHS staff attitudes towards user involvement. These data are not without limitations. First, although the CPQ (Kent and Read 1998) was developed in close collaboration with experienced mental health services users, it should be critically evaluated in the light of our findings of the high interrelatedness of the items from the various topics. It remains unclear whether the items really represent valid indicators for the constructs in focus. Second, the selected study population was selected to be representative for CAMHS employees in Norway with respect to their work place and professions with client contact. The 42% response rate is suboptimal but similar to other studies on this topic However, it was impossible to perform a drop-out analysis and adjust for any non response bias because of the anonymous nature of the investigation.

It appears that leaders and specialists, together with specialized CAMHS and more highly educated staff members were overrepresented in the sample. It is possible that this led to a positive response bias. For example, the responding staff members may have subjectively experienced pressure to present their services in a positive light given the government’s strategic plan (2003). This interpretation is supported by the number of ‘Don’t know’ and missing answers especially relating to evaluation aims, that may suggest that many staff members are unaware of these issues, or that user involvement procedures are not subjectively experienced by staff as meaningful or integrated tasks. The high number of missing answers (two-thirds) regarding the question about probable changes in CAMHS if users were employed may indicate a clear negative attitude towards such involvement. This assumption is supported by undecided attitudes towards user involvement in planning and/or delivery of CAMHS expressed by members of the more highly educated professions and those with clearly defined therapeutic duties.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that it is necessary to develop a shared understanding between policy makers, users and staff members about what user involvement should and/or can be. Some aspects of user involvement appear to be perceived as an implicit element of their daily work by the Norwegian CAMHS staff, particularly at the level of the individual user-staff member interaction. Under the auspices of developing a shared understanding of user involvement future investigations need to explore in depth the myriad of ways of involving users and possible outcomes of user involvements for the users, the various staff members, the service agency, and the service system. Moreover, a thorough evaluation of newly implemented user involvement actions should be undertaken to enable policy makers to make evidence-based decisions. Current evidence suggests only that user involvement, especially at the management level, does not have a negative impact upon services, without providing positive evidence of benefits accruing from such involvement (Simpson and House 2002).

References

Barley, V., Tritter, J., Daykin, N., Evans, S., McNeill, J., & Turton, P. (2007). Good practice for user involvement. http://www.dh.gov.uk/n/Policyand guidance/Researchanddevelopment/HealthinPartnership/Thestudies/DH_4127449. Retrieved 24 July 2008.

Brislin, R. W. (Ed.). (1976). Translations: Applications and research. New York: Wiley/Halsted.

Brody, D. S., Miller, S. M., Lerman, C. E., Smith, D. G., & Caputo, G. C. (1989). Patient perception of involvement in medical care: relationship to illness attitudes and outcomes. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 4, 506–511. doi:10.1007/BF02599549.

Bryant, M. (2008). Introduction to user involvement. The Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health. http://www.scmh.org.uk/80256FBD004F3555/vWeb/flKHAL6H9G4N/$file/introduction+to+user+involvement.pdf. Retrieved 24 July 2008.

Chinman, M. J., Weingarten, R., Stayner, D., & Davidson, L. (2001). Chronicity reconsidered: improving person-environment fit through a consumer-run service. Community Mental Health Journal, 37, 215–229. doi:10.1023/A:1017577029956.

Collins, F., Sheils, R., Peacock, G., Bannon, L., & Viers, N. (2004). Survey of consumer and carer experience of Victorian public child and adolescent mental health services 2003/2004. Statewide sector report. Sandringham: TQA Research Pty. Ltd.

Crawford, M. J., & Rutter, D. (2004). Are the views of members of mental health user groups representative for those of ‘ordinary’ patients? A cross-sectional survey of service users and providers. Journal of Mental Health, 13, 561–568. doi:10.1080/09638230400017111.

Delsignore, A., Carraro, G., Mathier, F., Znoj, H., & Schnyder, U. (2008). Perceived responsibility for change as an outcome predictor in cognitive-behavioural group therapy. The British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 47, 281–293. doi:10.1348/014466508X279486.

Farina, A., & Fisher, J. D. (1982). Beliefs about mental disorders: findings and implications. In G. Weary & H. L. Mirels (Eds.), Integrations of Clinical, Social Psychology. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Felton, C. J., Stastny, P., Shern, D. L., Blanch, A., Donahue, S. A., Knight, E., et al. (1995). Consumers as peer specialists on intensive case management teams: impact on client outcomes. Psychiatric Services (Washington, D.C.), 46, 1037–1044.

Garber, J., & Seligman, M. E. P. (Eds.). (1980). Human helplessness: Theory and applications. New York: Academic Press.

Grace, S. L., Abbey, S. E., Shenk, Z. M., Irvine, J., Franche, R. L., & Stewart, D. E. (2002). Cardiac rehabilitation II: referral and participation. General Hospital Psychiatry, 24, 127–134. doi:10.1016/S0163-8343(02)00179-2.

Greenfield, S., Kaplan, S., & Ware, J. E. (1985). Expanding patient involvement in care. Annals of Internal Medicine, 102, 520–528.

Griffiths, H., & Jordan, S. (1998). Thinking of the future and walking back to normal: an exploratory study of patients’ experiences during recovery from lower limb fracture. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 28, 1276–1288. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2648.1998.00847.x.

Kaba, R., & Sooriakumaran, P. (2007). The evolution of the doctor-patient relationship. International Journal of Surgery, 5, 57–65. doi:10.1016/j.ijsu.2006.01.005.

Katan, J., & Prager, E. (1986). Consumer and worker participation in agency-level decision-making: Some considerations of their linkages. Administration in Social Work, 10, 79–88.

Kent, H., & Read, J. (1998). Measuring consumer participation in mental health services: are attitudes related to professional orientation? The International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 44, 295–310. doi:10.1177/002076409804400406.

Kristensson-Hallström, I., Elander, G., & Malmfors, G. (1997). Increased parental participation in a paediatric surgical day-care unit. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 6, 297–302. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2702.1997.tb00318.x.

Lefley, J. (1990). Culture and chronic mental illness. Hospital & Community Psychiatry, 41, 277–286.

Lewis, L. (2004). User involvement in mental health services: A study in Grampian. University of Aberdeen. http://www.aberdeenccn.info/nmsruntime/saveasdialog.asp?lID=499&sID=13. Retrieved 24 July 2008.

Middelton, P., Stanton, P., & Renouf, N. (2004). Consumer consultants in metal health services: addressing the challenges. Journal of Mental Health, 13, 507–518. doi:10.1080/09638230400004424.

Nelson, R. A., & Borkovec, T. D. (1989). Relationship of client participation to psychotherapy. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 20, 155–162. doi:10.1016/0005-7916(89)90048-7.

Nyland, J., Johnson, D. L., Caborn, D. N., & Brindle, T. (2002). Internal health status belief and lower perceived functional deficit are related among anterior cruciate ligament-deficient patients. Arthroscopy, 18, 515–518. doi:10.1053/jars.2002.32217.

Regeringens strategiplan for barn og unges psykiske helse. (2003) Together for mental health (‘… sammen om psykisk helse…Norwegian). http://www.regjeringen.no/upload/kilde/hd/bro/2003/0004/ddd/pdfv/187063-s.pdf. Retrieved 24 July 2008.

Regulations No. (2001). 676 of 8 June 2001 on individual plans under health legislation. Norsk Lovtidend. Part I, 8, 1092–1109

Rotter, J. B. (1966). Generalized expectancies for internal versus external control of reinforcement. Psychological Monographs, 80(1), 1–28.

Sartorius, N., & Kuyken, W. (1994). Translation of health status instruments. In J. Orley & W. Kuyken (Eds.), Quality of life assessment: International perspectives (pp. 3–18). Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Verlag.

Schwarzer, R. (Ed.). (1992). Self-efficacy: Thought control of action. Philadelphia: Hemisphere Publishing.

Simpson, E. L., & House, A. O. (2002). Involving users in the delivery and evaluation of mental health services: systematic review. British Medical Journal, 325, 1265–1268. doi:10.1136/bmj.325.7375.1265.

Simpson, E. L., & House, A. O. (2003). User and carer involvement in mental health services: from rhetoric to science. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 183, 89–91. doi:10.1192/bjp.183.2.89.

Soffe, J., Read, J., & Frude, N. (2004). A survey of clinical psychologists’ views regarding service user involvement in mental health services. Journal of Mental Health, 13, 583–592. doi:10.1080/09638230400017020.

Tait, L., & Lester, H. (2005). Encouraging user involvement in mental health services. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 11, 168–175. doi:10.1192/apt.11.3.168.

Telford, R., & Faulkner, A. (2004). Learning about service user involvement in mental health research. Journal of Mental Health, 13, 549–559. doi:10.1080/09638230400017137.

Tew, J., Townend, M., Hendry, S., Ryan, D., Glynn, T., & Clark, M. (2003). On the road to partnership? user involvement in education and training in the West Midlands. Executive summary and recommendations. http://www.mhhe.heacademy.ac.uk/docs/external/ontheroad.doc. Retrieved 24 July 2008.

Worrall-Davies, A. (2008). Barriers and facilitators to children’s and young people’s view affecting CAMHS planning and delivery. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 13, 16–18. doi:10.1111/j.1475-3588.2007.00456.x.

Worrall-Davies, A., & Marino-Francis, F. (2008). Eliciting children’s and young people’s views of child and adolescent mental health services: a systematic review of best practice. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 13, 9–15. doi:10.1111/j.1475-3588.2007.00448.x.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Anne Andersen, Inger Hodne and Knut Halvard Bronder who took part in the planning and implementation of this work and were members of the project group. Thanks are also due to the participants in this study and to the leaders at all clinics who helped distribute the questionnaire. Thanks are also due to Professor Horwitz for her guidance and comments on this piece. The project was carried out with financial support from the Norwegian Directorate of Health and Social Services.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix 1

Appendix 1

Substantial relationships between CPQ items; Norwegian CAMHS version; χ 2 scores; p.

-

Item 1 with item 2.aN: χ 2 (4) = 58.61; p < 0.001/item 2.bN: χ 2 (4) = 32.83; p < 0.001/with item 8: χ 2 (4) = 15.81; p = 0.003/with item 9: χ 2 (4) = 15.33; p = 0.004/with item 12: χ 2 (4) = 14.96; p = 0.005.

-

Item 2.aN: with item 2.bN: χ 2 (4) = 95.80; p < 0.001/with item 15: χ 2 (4) = 13.85; p = 0.008.

-

Item 2.bN: with item 15: χ 2 (4) = 16.96; p = 0.002/with item 19.1: χ 2 (2) = 9.58; p = 0.008.

-

Item 3: with item 4: χ 2 (4) = 52.03; p < 0.001/with item 10: χ 2 (4) = 18.57; p < 0.001/with item 12: χ 2 (4) = 14.56; p = 0.006.

-

Item 6N: with item 11: χ 2 (4) = 32.49; p < 0.001/with item 16: χ 2 (4) = 17.23; p = 0.002.

-

Item 7N: with item 6: χ 2 (20) = 70.27; p < 0.001/with item 14: χ 2 (16) = 33.29; p = 0.007/with item 16: χ 2 (8) = 29.88; p < 0.001/with item 19.3: χ 2 (4) = 15.45; p = 0.004 with item 20.6: χ 2 (4) = 14.01; p = 0.007.

-

Item 8N: with item 14: χ 2 (16) = 41.14; p = 0.001.

-

Item 6: with item 14: χ 2 (20) = 37.53; p = 0.010/with item 15: χ 2 (10) = 23.16; p = 0.010.

-

Item 7: with item 13: χ 2 (4) = 14.99; p = 0.005/with item 16: χ 2 (4) = 13.70; p = 0.008.

-

Item 8: with item 9: χ 2 (4) = 57.90; p < 0.001/with item 10: χ 2 (4) = 15.20; p = 0.004/with item 12: χ 2 (4) = 18.62; p = 0.001/with item 20.1: χ 2 (2) = 9.46; p = 0.009.

-

Item 8: with item 20.6: χ 2 (2) = 12.41; p = 0.002.

-

Item 9: with item 10: χ 2 (4) = 17.64; p = 0.001/with item 11: χ 2 (4) = 30.89; p < 0.001/with item 12: χ 2 (4) = 17.89; p = 0.001/with item 16: χ 2 (4) = 14.45; p = 0.006.

-

Item 11: with item 16: χ 2 (4) = 19.90; p = 0.001.

-

Item 12: with item 20.1: χ 2 (2) = 9.58; p = 0.008.

-

Item 13: with item 20.1: χ 2 (2) = 10.13; p = 0.006.

-

Item 14: with item 16: χ 2 (4) = 67.44; p < 0.001.

-

Item 15: with item 19.2: χ 2 (2) = 14.63; p = 0.001/with item 20.2: χ 2 (2) = 15.42; p < 0.001.

-

Item 16: with item 20.6: χ 2 (2) = 13.96; p < 0.001.

-

Item 17: with item 18: χ 2 (24) = 45.95; p = 0.004/with item 20.3: χ 2 (6) = 19.49; p = 0.003/with item 20.6: χ 2 (6) = 19.48; p = 0.003/with item 20.7: χ 2 (6) = 19.52; p = 0.003/with item 20.8: χ 2 (6) = 32.74; p < 0.001.

-

Item 18: with item 19.3: χ 2 (4) = 16.20; p = 0.003/with item 19.4: χ 2 (4) = 13.24; p = 0.010/with item 20.3: χ 2 (4) = 23.57; p < 0.001/with item 20.5: χ 2 (4) = 23.27; p < 0.001/with item 20.7: χ 2 (4) = 14.43; p = 0.006/with item 20.8: χ 2 (4) = 20.10; p < 0.001.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Richter, J., Halliday, S., Grømer, L.I. et al. User and Carer Involvement in Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services: A Norwegian Staff Perspective. Adm Policy Ment Health 36, 265–277 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-009-0219-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-009-0219-x