Abstract

The transition to middle/junior high school is associated with declines in students’ academic performance, especially among low-income, urban youth. Developmental psychologists posit such declines are due to a poor fit between the needs of early adolescents—industry, identity, and autonomy—and the environment of their new schools. Extracurricular participation during these years may act as a buffer for youth, providing a setting for development outside the classroom. The current study examines participation within and across activity settings among low-income, urban youth in New York City over this transition. Using the Adolescent Pathways Project data, this study explores how such participation relates to course performance. We find that a large percentage of youth are minimally or uninvolved in extracurricular activities during these years; that participation varies within youth across time; and that the association between participation and course performance varies by activity setting. Youth who participate frequently in community or athletic settings or have high participation in two or more settings are found to have higher GPAs in the year in which they participate and youth who participate frequently in the religious setting are found to have lower GPAs. High participation in more than two settings may be detrimental.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Extracurricular participation, defined as structured participation in organized group activities outside of the regular school curriculum, has been linked to a range of positive academic outcomes, including better grades and increased educational attainment (e.g., Eccles et al. 2003). Breadth of participation (across different types of activities) has also been linked to positive academic outcomes (e.g., Peck et al. 2008). Additionally, research indicates the middle grades as central to students’ later academic trajectories (Balfanz et al. 2007; Kieffer and Marinell 2012), a critical period for youth identity formation (Erikson 1968), and a time of particular risk of academic disengagement (Eccles and Midgley 1989). This is especially true for low-income, urban, minority youth (Simmons et al. 1991), a group for whom extracurricular participation may be particularly protective (see Guest and Schneider 2003). Together, this literature suggests extracurricular participation may provide additional developmental spaces, or activity settings, for early adolescents and, in doing so, act as a protective factor for those at risk of academic disengagement and later school failure.

Despite the potential importance of extracurricular participation during these years, the early adolescent period has been largely overlooked in the extracurricular literature (which focuses on high school youth) and the after-school literature (which focuses on elementary school youth), especially as it pertains to low-income, urban youth and school performance. If extracurricular participation is protective against declines in school performance, one might expect it to be most beneficial for youth at highest risk of such declines (Editorial Projects in Education 2012; Swanson 2009) during the years when their trajectories begin to diverge into those on-track to graduate high school and those not (Balfanz et al. 2007; Kieffer and Marinell 2012; Roderick 1994). One also might expect this influence to vary by the specific activity setting, as different settings are likely to be correlated with different identity formations (Eccles et al. 2003). Despite this, there is a dearth of literature on both the frequency and types of extracurricular participation low-income, urban youth participate in and any associations between these dimensions of participation and students’ performance in school.

With a sample of low-income, urban early adolescents, this study explores youth participation in extracurricular activities across four settings—school, community, religious, and athletic—and the relation between participation and course performance over the transition to middle grade schools. This study seeks to, first, describe participation within this population with a focus on frequency and activity setting. It then examines whether participation in extracurricular activities during these years is associated with academic performance and, if so, whether this varies by activity setting. Lastly, this study tests whether high participation across settings—or breadth of participation—is related to academic performance. The answers to these questions will inform the role of extracurricular participation in promoting course performance as well as future extracurricular participation research among this population.

Academic Performance, Activity Settings, and Early Adolescence

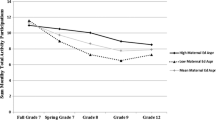

Urban, low-income youth (the majority of whom are African American or Hispanic) are at particular risk of high school dropout (Editorial Projects in Education 2012; Swanson 2009), an outcome strongly predicted by middle grade performance. Kieffer and Marinell (2012), in New York City (NYC), and Balfanz et al. (2007), in Philadelphia, examine large cohorts of urban youth and find that changes in course achievement and emergent course failure in 6th–8th grade strongly predict 9th grade on-track status and high school completion. At the same time, the transition to middle grade schools itself is risky, especially for this population (Simmons et al. 1991). This transition is associated with declines in academic achievement in studies that look solely at youth making the transition (e.g., Espinoza and Juvonen 2011) and in more rigorous studies comparing those who transition to students in K-8 schools (e.g., Byrnes and Ruby 2007; Rockoff and Lockwood 2010). Youth who experience a drop in grades over this transition have been found to be more likely to drop out of school, regardless of future academic performance (Roderick 1994).

The transition from elementary to middle school is hypothesized to be risky as a result of a gap between early adolescents’ developmental needs and the middle grade school environment (Eccles and Midgley 1989). Developmental psychologists have identified early adolescence as critical to the development of industry, competency, identity, and autonomy (Erikson 1968), which have in turn been linked to intrinsic motivation, academic engagement, and performance (Ryan and Deci 2009). Yet, relative to elementary school students, those in middle grade schools feel more anonymous and less supported (Eccles and Roeser 2011). This anonymity and decrease in social support may be particularly pronounced in large, urban, or under-resourced schools where youth likely have fewer outside options for engagement (Wachs 1996).

This developmental mismatch combined with the theory of activity settings (O’Donnell and Tharp 2012; Vygotsky 1981) suggests a potentially positive role of extracurricular participation as a means to foster key competencies. In 1981, Vygotsky advanced the idea that development is rooted in activities with others. This idea was expanded upon (e.g., Gallimore et al. 1993) and has had the effect of positioning the activity setting as a central unit of analysis, influence, and potential social change. Activity settings theory posits that individuals’ cognitive, emotional, and behavioral development is influenced by shared activities with others (O’Donnell and Tharp 2012). In this way, extracurricular activities nested in the school, community, religious, and athletic contexts may create shared experiences that influence the identity formation of youth, ultimately impacting youth’s academic and social outcomes (see, for example, Eccles et al. 2003).

Extracurricular Participation and Academic Outcomes

Indeed, there is considerable evidence linking extracurricular participation to improved academic outcomes such as grades (Broh 2002; Knifsend and Graham 2012); educational attainment (Fredricks and Eccles 2006); test scores (Fredricks 2012); and academic engagement (Broh 2002; Knifsend and Graham 2012). Studies with middle and high school youth find access to participation to appear more open in the middle grades as opposed to high school, where participation seems to be more often limited to those who have participated in the past (Denault and Poulin 2009). This suggests early adolescence may be a good time for promoting extracurricular involvement. Additionally, in studies with ethnically or economically diverse samples, the relation between extracurricular participation and academic performance appears strongest among low-income, urban, minority youth (e.g., Guest and Schneider 2003).

As posited by activity settings theory, the influence of extracurricular participation on academic outcomes is likely to vary by type of activity. Different activities may emphasize different messages (e.g., teamwork) and in doing so create different shared meanings. Empirical work supports this. For example, Broh (2002) found sports and music to be associated with higher grades and increased time on homework but found no effects for yearbook, cheerleading, or vocational clubs. Since much of the literature linking participation to academic outcomes has focused on a particular setting of extracurricular activity, such as sports (Feldman and Matjasko 2005), this suggests value to exploring the link between a wide range of activity types and academic outcomes. There is also a need to better understand the influence of participation across activity types—or breadth of participation—on course performance. Research on breadth of participation (e.g., Fredricks and Eccles 2006; Peck et al. 2008) suggests that a youth who is “well-rounded” (e.g., participating in painting, basketball, and debate team) has better outcomes than an equally involved youth without such breadth (e.g., one who plays three sports). Peck et al. (2008), in examining students at high risk for low educational attainment, found increased college enrollment rates for youth involved in sports and volunteering as compared with sports or volunteering. This may be because these differently situated activities collectively and complementarily influence students’ identities and corresponding behavior. Sports may influence a youth’s identity as one able to make decisions under pressure, which might aide test performance. Volunteering, in turn, could empower a youth to identify as capable of creating positive results and thus increase perseverance in academic settings. Both are likely to promote teamwork, initiative-taking, and the frequency with which one asks for help when confronted with difficult assignments (Larson et al. 2005). In combination, these influences may promote academic success more than either might alone.

There is also concern that too many activities, or too much time involved in extracurricular activities, could be detrimental to academic success and optimal development. This is known as the ‘overscheduling hypothesis’ (Fredricks 2012). Where this has been empirically tested, it has been supported only at high levels of participation (Fredricks 2012; Marsh and Kleitman 2002; Rose-Krasnor et al. 2006). For example, Fredricks (2012) finds positive associations between participation and academic outcomes that level out and become negative for youth participating in 5–7 activities or more (with the turning point dependent on the academic outcome). These studies have generally used nationally representative (Fredricks 2012; Marsh and Kleitman 2002) or middle-income high school samples (Rose-Krasnor et al. 2006). There is little work examining the diversity of activities in which middle school youth, and especially low-income, urban middle-school youth, are involved and how this relates to academic performance.

The Current Study

The current study builds on the above literature through examining extracurricular participation and course performance within a low-income, urban, early adolescent population across the transition to middle grade school. While course performance is only one indicator of academic competence, and academic competence but one indicator of youth development, the strong predictive power of middle grade course performance on future educational attainment suggests that this is a critical outcome. This study has two overarching research aims:

-

1.

To describe the frequency of extracurricular involvement in the final year of elementary school and first 2 years of middle or junior high school with a focus on breadth of participation as well as stability of participation over time; and,

-

2.

To test associations between overall participation, types of participation, breadth of participation and course performance during these years.

This study is motivated by the hypothesis that extracurricular participation may act as a buffer for youth across the transition to middle grade schools, preventing losses in academic achievement, and that this association may vary by activity setting. This study tests predicted positive associations between participation, breadth of participation, and course performance while exploring potentially differential associations by setting. The aim is to further knowledge about extracurricular participation among urban, low-income youth, its association with middle grade performance, and its potential role in protecting high-risk youth from future school failure.

Method

Data for this study come from waves 1–3 of the NYC subsample of the Adolescent Pathways Project (APP) early adolescent cohort, a four-wave longitudinal study of low-income, urban youth (Seidman 1991). Schools were selected with the aim of ensuring ethnic diversity among this population and minimizing attrition. While this is an older data set, it has the advantage of focusing on low-income urban youth, including repeated extracurricular participation items across multiple contexts before and after the transition to a middle grade school, and inquiring about frequency as well as presence of participation. To be included a school with 50 % or more white students had to have 60 %, and a school with 80 % or more black or Latino students had to have 80 %, of the student body receiving free or reduced lunch. Elementary schools with defined feeder patterns, wherein the majority of students transition to the same middle grade school, were identified to facilitate follow up. The NYC cohort included 14 elementary schools.

Participants

All 5th or 6th graders in selected schools were recruited. Participation required active parental consent. Multiple steps, including extensive parent outreach, were taken to increase participation rates (see Seidman 1991), resulting in a 41 % participation rate. Participants did not differ significantly from same-grade, same-school non-participants in reading or mathematics standardized tests (Seidman 1991). Wave 1 data (N = 747) were collected between March and early June in the academic year preceding the transition to middle grade schools. Wave 2 (N = 575) and wave 3 (N = 554) data were collected between January and May of the following two years. Researchers visited schools multiple times in waves 2 and 3 to minimize attrition. Data were collected from students who left feeder school patterns to attend other NYC middle grade schools. Students who left the NYC school system were not followed.

For the current analyses, students with participation data in the final year of elementary school and either the first or second year of middle school were included (N = 625; 53.9 % female; 45.6 % Latino; 24.3 % black; 20.6 % white; 4.6 % Asian; 3.8 % black/Latino; 1.1 % other). The average age of participants in wave 1 was 11.31 years (SD = 0.89). Given the goals of the study, students only surveyed in the first wave, elementary school, were dropped, reducing the overall sample by 16 %. Students dropped were less likely to be white (21 vs. 7 %, p < 0.001) or Latino (36 vs. 46 %, p = 0.052); more likely to be black (39 vs. 24 %, p = 0.001) or of other ethnicity (8 vs. 1 %, p < 0.001); less likely to live with both birth parents (43 vs. 57 %, p = 0.006) and more likely to live with one birth parent (44 vs. 36 %, p = 0.091); less likely to have no caregivers with full-time employment (2 vs. 9 %, p = 0.022) and more likely to have two caregivers working full-time (17 vs. 11 %. p = 0.094). The ethnic and family structure differences suggest greater disadvantage among those dropped as compared with students remaining in this study and the family employment difference suggests greater advantage. There were no other statistical differences between the groups. Most participants lived in areas of high poverty, with over half residing in neighborhoods where 20 % or more of the families made under $10,000.

Procedure

Written surveys were administered to students in classrooms or common areas (e.g., the cafeteria). The number of students taking the survey in the same space concurrently depended on available space. A member of the research team read survey questions out loud. Monitors, trained by the research team and present in numbers proportional to the number of students, circulated to answer questions. Spanish translators were present if needed. Administration took one to two class periods during wave one and one class period during waves two and three.

Measures

The current study utilizes student surveys documenting involvement in extracurricular activities as well as student self-reported grade point average and student level covariates.

Extracurricular Participation

Students’ extracurricular participation was measured using a series of questions related to frequency of activity involvement in school, community, religious, and athletic settings. For school, community, and religious items, responses were on a six point scale from 0 = “Never or Almost Never” to 5 = “Almost Every Day.” For athletic items, options ranged from 1 = “Once a Month or Less” to 5 = “Almost Every Day.” Examples of items include student government (school), neighborhood improvement (community), youth group (religious), and team sports (athletic). For a full list and descriptive statistics see Table 1.

School Performance

School performance was measured using self-reported GPA. Students were asked: “What would you say your average grade is now, if you put all of your grades together?” Responses are: 5 = “A or 90–100”, 4 = “B or 80–89”, 3 = “C or 70–79”, 2 = “D or 65–69”, and 1 = “F or below 65.” Self-reported GPA has been shown to be highly correlated with administrative GPA (Dornbusch et al. 1991), and more highly correlated with graduating high school and attending college then official school GPA (Zimmerman et al. 2002). Average GPA in wave 1 was 3.86 (SD = 1.19).

Covariates

Research points to important differences in extracurricular participation level by demographic characteristics (Fredricks and Eccles 2006). In alignment with this research, this study included as covariates: race/ethnicity (1 = black; 2 = white; 3 = Latino; 4 = Asian; 5 = black/Latino; and 6 = other), family structure (1 = “I live with my birth (real) parents”; 2 = “I live with one of my birth or real parents”; 3 = “I live with my foster parents/other relatives/other”), and an indicator of family employment status. The indicator of family employment was derived from a series of questions as to the two financially responsible persons in the household asking whether such persons have a full time job, part time job, no job, or receive welfare. Responses take different forms in the raw data. Wave 1 has a single categorical variable and waves 2–3 have a series of separate indicator variables for each adult. For this study, family employment was categorized into one variable with eight categories from 0 (neither person has a job/receives welfare) to 7 (both persons work full-time).

Given that research suggests differences in extracurricular involvement by student motivation and engagement (Fredricks and Eccles 2006), we also include academic behavioral engagement as a covariate. This variable comprises four questions in which youth were asked on a four-point scale (1 = “rarely” to 4 = “almost always”) how often they come to class prepared, complete assigned homework on time, turn in neat, tidy homework, and work hard in school. These four items were combined via confirmatory factor analysis to obtain a factor score for each wave (RMSEA = 0.016; CFI = 0.998; TLI = 0.997). This analysis took into account the three-wave structure with factor loading invariance and correlated residuals across waves (Muthén and Muthén 1998–2012). Each item was constrained to have the same loading and was allowed to correlate with itself across waves.

Missing Data

As mentioned above, the 122 students (16.3 %) missing all post-elementary school data were excluded. An additional 68 (10.9 %) students were missing wave 2 data and 72 (11.5 %) were missing wave 3 data. Students who did not participate in wave 2 were more likely to be black (43 vs. 22 %, p < 0.001) or black/Latino (9 vs. 3 %, p = 0.024) and less likely to be white (23 vs. 10 %, p = 0.018) as compared to those who did. Students who did not participate in wave 3 had slightly lower GPAs in wave 2 (3.70 on a 1–5 scale vs. 3.94, p = 0.052). There were no differences between the groups in gender, family structure, family employment, wave 1 extracurricular participation, or wave 1 GPA.

Item level missingness, excluding students who did not participate at all in that wave, ranges from 1.6 to 21.8 % in wave 1, 0.4 to 13.8 % in wave 2, and 0.7 to 8.5 % in wave 3. Seventy-six percent of students in wave 1 are missing 3 or fewer items (of 27 used in our analyses) with the most common variable missing being family employment status. Those missing more than three items in wave 1 are more likely to be black (34 vs. 21 %, p = 0.002), less likely to be white (13 vs. 24 %, p = 0.006) or Asian (1 vs. 5 %, p = 0.025), more likely to have participated in athletic extracurricular activities in wave 1 (0.13 vs. −0.01, standardized values, p = 0.034), and had higher wave 1 GPAs (4.15 vs. 3.81, on a 1–5 scale, p = 0.020). There were no differences between the groups in gender, family structure, or wave 1 family employment. Ninety-five percent of students in wave 2 and 95 % of those in wave 3 are missing 2 or fewer items with most (89 and 90 %) missing 0 or 1.

To account for these missing values, all analyses used full information maximum likelihood (FIML). FIML and multiple imputation (MI) have been identified as the preferred methods for accounting for missing data (Graham 2009) with research showing them to produce nearly identical results (Collins et al. 2001).

Results

To address research aim 1, we first looked descriptively at the endorsement of participation items across waves. Next, we conducted an exploratory factor analysis (EFA), using Mplus 7.0 (Muthén and Muthén 1998–2012). This EFA included the 21 extracurricular items at three time points with factor invariance and correlated residuals across time. This model has sufficient constraints to generate factor scores. It allows like items to correlate across waves, restricts each item to load with the same loading on equivalent factors across waves, and allows generated latent factors to correlate with each other. Items loaded most strongly by activity setting and the overall model fit well (RMSEA = 0.018, CFI = 0.967, TLI = 0.963). We then ran a more parsimonious model such that each item loaded only on its highest loading factor.

To address research aim 2, we used the factor scores generated above, which are standardized measures, to run a mixed model (random plus fixed effects) analysis of standardized GPA on extracurricular participation controlling for the above covariates as well as school fixed effects. Standardization allows the found coefficients to be interpreted as effect sizes and also allows for more accurate comparison between models, which was particularly important in our follow-up post hoc analyses to assess concerns such as bi-directionality of influence. We ran these analyses using the sem command in Stata/SE 13.0 (2013). Using sem allowed for missing values to be accounted for with FIML. The mixed model allowed the intercept and slope to vary by student as well as co-vary with each other (random effects) while calculating between child fixed effects. In sem, this entailed regressing wave 1 GPA on wave 1 and time invariant predictors and school 1 (elementary school) fixed effects; wave 2 GPA on wave 2 and time invariant predictors and school 2 (middle school, first year) fixed effects; and wave 3 GPA on wave 3 and time invariant predictors and school 3 (middle school, second year) fixed effects. Some students changed schools again between waves two and three. Loadings on the predictors and covariates were constrained to be equal across waves.

This model is an improvement on a purely cross-sectional model in that it removes unexplained student level (random) variance from the fixed effects results and thus partially accounts for unmeasured differences between students. School fixed effects are used in lieu of a third level random effect both because all students change schools between waves one and two, a computationally difficult nesting structure, and because research suggests that school fixed effects are preferred when the primary interest is individual level inferences and the mechanism for selection into schools is not well accounted for in the data (Clarke et al. 2010). Intra class correlations (ICCs) were run before including school fixed effects. School attended explains 27, 0, and 5.6 % of the variance in GPA in waves 1–3, respectively.

Description of Extracurricular Participation (Aim 1)

Descriptively, 36 % of elementary and 40 % of middle grade students in this study report not participating in a single item in any setting more than once a month. Sixteen percent of middle school youth do not participate in any activity more than a few times a year. Lack of involvement also shows some persistence: 31 % of youth who are not involved in any activity more than a few times a year in the last year of elementary school remain uninvolved over the transition to middle school. Fifteen percent of students, who are at least minimally involved (i.e., at least one activity once a month) in elementary school become uninvolved over the transition.

Running the three-time point EFA, a four factor per wave model (12 factors total) was the best fit (RMSEA = 0.018; CFI = 0.967; TLI = 0.963). Items loaded highest by setting, such that all school-based activities loaded most strongly on factors 1, 5, and 9 (for waves 1–3), religious-based items on factors 2, 6, and 10, community-based items on factors 3, 7, and 11, and athletic items on factors 4, 8, and 12. No item loaded higher than 0.23 on a non-primary factor and most (87 %) loaded below 0.1 on off factors. Based on these results, we simplified this model such that each item loads only on its highest-loading factor (see Fig. 1 for item loadings and correlations between factors). This maintained equivalent fit (RMSEA = 0.019; CFI = 0.959; TLI = 0.955) with greater parsimony.

We examined these factor scores to further assess stability of, and trends in, involvement over time. Of our 625 students, 382 had involvement that fluctuated non-monotonically. The majority of these 382 (N = 166) increased involvement in the first year of middle school and then decreased it in the second year. A little under a third (N = 114) reported consistently low but slightly fluctuating involvement throughout the study, and the rest (N = 102) showed a dip in involvement in the first year of middle school. The next most prominent trend was steadily increasing involvement over time (N = 134, 21 %). There was no clear pattern of elementary involvement that preceded this trend: 40 (30 %) of these students showed low involvement in elementary school; 37 (28 %) had above average, but not high, involvement in one setting; 35 (26 %) had above average, but not high, involvement in two or more settings; and 22 (16 %) had high involvement in at least one setting (with 7 highly involved in two or more settings). The majority of these 22 students (64 %) increased both their breadth and intensity of involvement over time. Finally, 109 students (17 %) reported steadily decreasing involvement over time. Nearly half (43 %) of these students were highly involved in at least one setting in elementary school. One-sixth (16 %) had low initial levels of involvement that became even lower. The rest (41 %) had an average level of involvement in elementary school that decreased over the transition to middle school. Within our sample, there are no clear patterns indicating that involvement in particular settings is more or less associated with any of these trends.

There is evidence of participation across settings. The setting level factors in the confirmatory factor model are correlated 0.35–0.48 in the final year of elementary school (wave 1) and 0.30–0.69 in the second year of middle school (wave 3), with the exception being that religious and athletic participation are not highly correlated in either wave. In the first year of middle school (wave 2), the correlations are higher: 0.68–0.80 between the school, religious, and community settings. Students involved in school, religious, or community activities in the first year of middle school are significantly more likely to also be involved in one of the other two settings. Correlations within setting across waves are also in the 0.37–0.65 range. Correlations of this magnitude indicate some stability in participation over time as well as a substantial amount of change by individual students. They also indicate that participation in one setting is much more highly related to participation generally (in other settings) in the first year following the transition to middle school.

Influence of Participation on Course Performance (Aim 2)

Findings indicate that, with all covariates in the model as well as all other participation variables, a student with 1 standard deviation higher community-based extracurricular participation has a 0.14 standard deviation higher GPA (p = 0.001), a student with 1 standard deviation higher religious-based extracurricular participation has a 0.10 standard deviation lower GPA (p = 0.007), and a student with 1 standard deviation higher athletic-based extracurricular participation has a 0.08 standard deviation higher GPA (p = 0.026). There is no significant effect as a result of school-based participation. For comparison, a student with 1 standard deviation higher overall extracurricular participation, not controlling for setting specific participation, has a 0.08 standard deviation higher GPA (p < 0.001). Controlling for all the other variables as well as school fixed effects there is no significant effect of time on GPA variance (see Table 2 for complete model). This indicates that time trends in GPA, with GPA decreasing on average across the transition to middle grade schools, are fully explained by the included covariates. Student random effects (intercept and slope) account for 40 % of the remaining unexplained variance. Additionally, school attended and student classroom behavioral engagement have the largest associations with GPA. This suggests that there was value to the choice to include random effects, and thus account for some of the unexplained student level variance, as well as school fixed effects. We examine the role of classroom behavioral engagement, both as a covariate and as a potential mechanism through which extracurricular participation might influence course performance, in further detail below.

To assess the association between being involved in activities across settings (breadth of participation) and GPA, we re-ran the above model with the inclusion of an indicator variable for high involvement (1 standard deviation above the mean on that setting’s involvement factor) in two or more activity settings. Being highly involved in two or more settings was marginally associated with a 0.060 standard deviation increase in GPA (p = 0.075). Including this variable lessened the magnitude and significance of the community (β = 0.060; p = 0.075) and religious (β = −0.066; p = 0.077) associations but did not substantially change the association with athletic participation (β = 0.083; p = 0.014). We also examined a variation of this model that included an indicator of high participation in three or more settings in addition to that for high participation in two or more settings in order to test for any indication of a curvilinear relation between breadth of involvement and GPA. There is suggestive evidence that being highly involved in more than three settings may be detrimental to academic performance (β = −0.198; p = 0.054). This inclusion increased the strength of our findings as to involvement in two or more settings (β = 0.083; p = 0.020) and community involvement (β = 0.083; p = 0.020) and did not substantially change our findings as to religious (β = −0.066; p = 0.073) or athletic involvement (β = 0.083; p = 0.014). Only 3.7, 11.4, and 7.2 % of the students are highly involved in three or more settings in waves 1, 2, and 3, respectively.

Post Hoc Analyses

We ran a number of additional analyses to strengthen our confidence in and further explore the findings presented above.

Religious Participation and Course Performance

The negative association between participation in religious-based activities and course performance was contrary to our expectation. In an attempt to rule out alternative explanations for this association, we ran two variations of the model presented in Table 2: first including type of religion and then frequency of church attendance. Neither variable was significant and neither changed the central findings. Furthermore, religious participation is not highly correlated with ethnicity in any wave and thus likely not yielding findings conflated with ethnic status. In a limited run looking only at complete cases, we also found that within-person change in religious participation above one’s own mean negatively predicted GPA. This suggests that the association is likely not, or at least not fully, attributable to a time invariant omitted variable such as parental education. This combination of checks suggests that the negative association is, at minimum, a persistent finding.

Classroom Behavioral Engagement

One concern with the model presented above is the use of classroom behavioral engagement as a covariate. While this choice is supported by research indicating that academically engaged youth are more likely to participate in extracurricular activities (Fredricks and Eccles 2006), behavioral engagement is also a potential mechanism through which participation might influence course performance. Extracurricular participation has been linked to increased time spent on homework and academic engagement (Broh 2002; Knifsend and Graham 2012). Additionally, activity settings theory posits that participation might foster additional effort and engagement in school through changing youth’s self-identification and beliefs as to the returns to such effort.

To better disentangle the role of classroom behavioral engagement in relation to extracurricular participation and GPA, we ran three additional models. First we ran the model presented in Table 2 without the behavioral engagement measure. This increased, and made significant, the association between female and GPA, increased the magnitude of association for athletic-based participation, and slightly increased the magnitude of the school fixed effects in the middle grade waves of data, but had no substantial impact on the association with school-, religious-, or community-based extracurricular participation. Second, we ran a model predicting classroom behavioral engagement from extracurricular participation and all other included covariates without GPA in the model. In this model, school participation does significantly predict classroom behavioral engagement (β = 0.072, p = 0.006) as does being female (β = 0.294, p < 0.001). Nothing else, including the other participation measures, does, a finding that remains true when the model is re-run including the indication for high participation across settings. Third, we ran one more model predicting school extracurricular participation using classroom behavior engagement and the other covariates in our main model, including the other participation variables. Given that our model produces standardized regression coefficients, the coefficient values from this model can be directly compared to the prior model. Classroom behavioral engagement predicts school participation to nearly the same degree (β = 0.058, p = 0.002) as school participation predicts classroom behavioral engagement. This suggests that while classroom behavioral engagement and school-based extracurricular participation are correlated, it would be difficult to disentangle directionality of these two measures. Furthermore, of these two, only behavioral engagement appears to be associated with GPA.

Directionality of Findings

Given the non-causal nature of this study, we also tested to see if GPA predicts participation. We ran four models for each of the participation contexts adding GPA as a predictor and controlling for the other three contexts. GPA does significantly predict community-, religious-, and athletic-based participation, though all at lower magnitudes than participation in those domains predicts GPA. It predicts community-based participation at approximately 1/7 the magnitude (β = 0.021, p = 0.039), religious-based participation at 1/5 the magnitude (β = −0.021, p = 0.025), and athletic-based participation at 2/5 the magnitude (β = 0.033, p = 0.006). GPA does not significantly predict school participation. In a fifth model predicting high participation in two or more settings controlling for all four participation contexts, GPA predicts breadth of participation at approximately 2/5 the magnitude (β = 0.026, p < 0.001) of that which breadth predicts GPA. This suggests that while GPA likely influences participation (e.g., the need to maintain a minimum GPA in order to participate), the association from extracurricular participation to GPA is stronger.

Discussion

There are several key findings from this study. First, a large number of low-income, urban youth do not participate in any extracurricular activities. Second, there is substantial fluctuation in students’ participation, suggesting an opportunity for influencing student involvement. Third, community and athletic participation are both positively related to students’ course performance while religious participation is negatively related to course performance. Fourth, participation across settings may further support students’ academic performance beyond the influence of any one activity setting, if not done in excess. Taken together, these last two findings suggest a potential buffering effect of extracurricular participation generally, that may be heightened when pursued across two types of activity settings, along with a need to more deeply examine the features and role of the specific settings in which youth are involved.

While the effect sizes found are small, they are not insubstantial when examined both in the context of the data and in contrast to other work looking at similar outcome measures, two recommended benchmarking techniques in interpreting effect sizes (Hill et al. 2008). First, relative to the data at hand, the effect size of the association between community participation and GPA (β = 0.140, p = 0.001) is slightly larger than that of being female (β = 0.125, p = 0.018) in a reduced model looking at GPA predicted by time invariant student demographics. The gender gap in relation to GPA and subsequent educational attainment is the topic of a large body of work and widely considered to be of practical significance (see, e.g., DiPrete and Buchmann 2013). Second, relative to other research on youth academic achievement, effect sizes found in this paper relate favorably to those found due to having a teacher of one standard deviation higher quality (β = 0.10) or ten years more experience (β = 0.15–0.18; Rockoff 2004). Thus, while the effect sizes found for participation are lower than those for measures more explicitly related to classroom performance (e.g., classroom behavioral engagement), they are still both statistically and practically significant.

Frequency and Types of Participation

Findings indicate that, within this population, a large percentage of youth do not participate in any school, community, religious, or athletic extracurricular activity on a regular basis. Given research linking participation to a range of positive outcomes (e.g., Eccles et al. 2003) with especially strong associations for low-income, urban youth (Guest and Schneider 2003), this descriptive finding is important. A lack of participation during these formative years may indicate a missed developmental opportunity for fostering positive engagement and identity through shared activities (see O’Donnell and Tharp 2012) within this population.

Patterns of participation are highly variant suggesting there is likely a range of factors influencing youth’s involvement. These patterns, along with the finding of moderate, but not high, levels of persistence over time, could support theories that indicate early adolescence as a time for trying on identities (see Clements and Seidman 2002). Youth may be entering and discontinuing involvement in different activity settings in an attempt to find an identity—or common experience—that supports their developmental needs. To the degree that these needs are not supported by the school environment (Eccles and Midgley 1989), this involvement is likely more critical. This finding also highlights the value in exploring cross-setting involvement and in better understanding how different activities might differentially influence outcomes.

Community Participation

Community participation was found to be most highly associated with better course performance. The inclusion of the classroom behavioral engagement measure as a covariate, as well as the results of post hoc analyses, suggest that this is operating through a pathway distinct from that of increased homework completion or similar behaviors. Instead, youth may be developing new senses of themselves, their role in their community, and their ability to excel in pursuits such as school. Activity settings theory states that through shared activities, participants develop common meanings that influence their cognitive and behavioral development (O’Donnell and Tharp 2012). The community participation items in this study relate to neighborhood betterment, youth organizations, and community volunteering. These activities may enhance youth’s sense that they can enact positive change in their neighborhood and influence their environment. In a study of community college students, Giles Jr. and Eyler (1994) found that community service increased individuals’ belief that people can make a difference. Extending this to behavioral outcomes, Youniss et al. (1999), in a survey of high school students, found community service to be the strongest predictor of both conventional (e.g., voting) and unconventional (e.g., boycotting) political behavior. In line with these studies, community participation within our sample might alter youth’s sense of themselves (identity) as able to change settings and outcomes (industry and autonomy): key early adolescent developmental needs. This shared meaning may also lead to youth feeling more able to influence their academic outcomes—and thus to higher grades (for a meta-analysis of the relation between control expectancies and academic achievement, see Kalechstein and Nowicki Jr. 1997).

Athletic Participation

Athletic participation also significantly predicted increased course performance. This finding suggests that sports—as a shared activity—may have a positive role in influencing outcomes in early adolescence. Indeed, Brint and Cantwell (2010) found that undergraduates who indicated a greater degree of “activating” uses of time, such as sports and volunteering, also indicated a higher frequency of seeking help from professors, extensively revising a paper, and working with a group outside of class. Athletic involvement involves mastery of skills, ability to make decisions under pressure, the need to practice, and an increasing sense of competence as one improves. These could contribute to the creation of a shared meaning that says that success takes work, which might then translate into the classroom. Additionally, physical activity has itself been directly linked to academic outcomes, such as GPA (Rasberry et al. 2011).

School-Based Participation

In contrast, this study did not find a significant association between school-based activities and academic performance. This is surprising given that school-based activities include activities such as theater that might be thought to foster feelings of ability to create something through personal and group effort, similar to the theory behind some of the community-based activities. One hypothesis for this counterintuitive finding is that, in schools mismatched to students’ developmental needs, the activities within the school setting may be less effective. For example, if youth perceive low emotional support and a reduced sense of belonging at school during these years (Eccles and Roeser 2011), they may also experience low support and belonging in the school-based activities run by the same or similar adults and operating under the same or similar settings-based norms. Additionally, the school-based setting items by and large do not contain the component of environmental betterment or service that the community participation items do. One exception to this is student government. However, depending on school norms, there is likely to be a limit to how much change student leaders are able to enact. The actual shared activity in activity settings theory, such as community betterment, is critical to the shared meanings formed by the participants. School-based activities may not be creating a sense of ability to proactively affect change and influence one’s environment. This sense of ability, in turn, may be particularly critical for students that experience significant socio-economic disadvantage and barriers to affecting change and may have a substantial impact on their self-perception as individuals able to succeed and excel.

Religious Participation

Finally, religious participation was found to be significantly associated with decreased course performance. The negative effect for religious participation, robust across multiple models, is surprising. This finding contradicts a number of studies in which associations have been found between religious participation, such as youth group (see Eccles and Barber 1999) and church attendance (see Regnerus and Elder Jr. 2003) and academic achievement. Research has also linked parents’ religious participation to children’s educational attainment (Eirich 2012) suggesting that if youth who are involved in religious activities have parents who are also involved, we would further expect a positive association between participation and academic outcomes.

This study does support the findings of one prior study, conducted within this same low-income, urban population during the high school years. Pedersen et al. (2005) found exhibiting strong religious connection, as measured by involvement in religious activities and belief in God, to be associated with lower academic engagement and achievement. Activity settings theory may help explain why aspects unique to religious participation, and why high participation in only religious activities, might be detrimental within a low-income, urban context. Due to ethnic and racial stereotypes surrounding academic performance, the shared meaning created by such activities may actually run counter to positive academic identity formation and thus lead to more negative academic performance within this population. For example, Markstrom (1999) found higher religiosity among African-American youth to be associated with increased ethnic identity. Given work indicating an association between racial group identity and anti-academic stereotypes, such as negative attitudes toward school (see, e.g., Peterson-Lewis and Bratton 2004), this suggests a potential avenue through which the religious activity setting might decrease youths’ identification with school and thus their course performance. For youth who participate in multiple settings, this possible stereotype bias might be counteracted or balanced by the identities fostered through other activities.

High Levels of Participation Across Settings

A high level of participation in two or more settings was marginally associated with increased course performance controlling for participation by setting as well for students’ classroom behavioral engagement. This association became significant upon the inclusion of an indicator for high participation in three or more settings, a variable associated with decreased course performance. These findings support both the potential importance of breadth of participation (Fredricks and Eccles 2006; Peck et al. 2008) and concerns that too many activities, at high intensity, might be detrimental (Fredricks 2012). Given the small number of youth involved at this level, and the high number of uninvolved or only minimally involved youth, these findings still suggest that most youth would benefit from increased, and more diverse, involvement. They do, however, indicate a need to be aware on a more individual basis of a student’s commitments.

A key pathway through which high participation across two settings might increase academic performance comes from developmental theory, which indicates early adolescence as a time for developing industry, identity, and autonomy (Clements and Seidman 2002; Eccles and Midgley 1989; Erikson 1968). Active involvement in divergent settings is likely to better facilitate one’s pursuit of self-identity as well as to increase feelings of industry and autonomy, opportunities for decision-making, and avenues of social support. Indeed, Pedersen et al. (2005) found higher self-esteem and lower depression among highly involved high school youth. These pathways are likely to be associated with higher success in (and connectedness to) school even given the same level of reported effort. Additionally, being involved in different types of activities during the middle grades may also open up the opportunity for greater involvement in youth’s later years (Denault and Poulin 2009) and as such may act as a (continuing) buffer against disengagement and low esteem.

Strengths, Limitations, and Future Directions

Strengths of this study include the broad range of extracurricular participation data, the rigorous measurement analysis examining the factor structure of extracurricular participation, and the sample of low-income, ethnic minority, early adolescents. The study is limited by reliance on student report measures, absence of information on quality of activities, and lack of settings-level data. Quality of, and components present in, different activities would allow us to test the theorized explanations for our findings and better understand differential impacts by activity setting. Likewise, settings-level data on schools and neighborhoods would better inform the level of access students have to safe and productive extracurricular activities; the level of family encouragement and support as to extracurricular participation; and the peer norms regarding extracurricular involvement. Access to activities is critical both in interpreting our findings and in promoting greater activity participation among low-income, urban populations in the future.

Additionally, unbalanced attrition and missing data rates raise generalizability concerns. We may be lacking information on youth most likely to be disadvantaged. Finally, although the longitudinal, repeated measures format of the data allowed for mixed methods analyses and thus a more explicit modeling of change over time, the correlational nature of the data does not allow for causal claims. Research and policy would benefit greatly from future work examining the causality of these associations. For example, would increasing community participation improve outcomes for youth not currently participating? What are the effects of increasing the number of opportunities in a youth’s neighborhood? The current study adds support and motivation for such research.

Conclusion and Implications

This study informs our understanding of low-income youth’s extracurricular participation and lends support to the potentially buffering effect of certain types and combinations of extracurricular participation across the transition to middle grade schools. Our findings, which show a moderate to high degree of movement between activities over time, also suggest that participation is pliable in these years. There is room for encouraging new, different, or increased involvement. Although future studies are needed to support causal pathways between types of extracurricular participation and course performance, this study highlights the potential importance of participation across settings, as well as community and athletic participation specifically, in supporting low-income, urban youth’s academic outcomes. Structured and positive extracurricular participation may be a crucial buffer as these youth navigate school transitions and schoolwork in the middle years.

References

Balfanz, R., Herzog, L., & Mac Iver, D. J. (2007). Preventing student disengagement and keeping students on the graduation path in urban middle-grades schools: Early identification and effective interventions. Educational Psychologist, 42(4), 223–235.

Brint, S., & Cantwell, A. M. (2010). Undergraduate time use and academic outcomes: Results from the University of California Undergraduate Experience Survey 2006. Teachers College Record, 112(9), 2441–2470.

Broh, B. A. (2002). Linking extracurricular programming to academic achievement: Who benefits and why? Sociology of Education, 75(1), 69–95.

Byrnes, V., & Ruby, A. (2007). Comparing achievement between K-8 and middle schools: A large-scale empirical study. American Journal of Education, 114(1), 101–135.

Clarke, P., Crawford, C., Steele, F., & Vignoles, A. F. (2010) The choice between fixed and random effects models: Some considerations for educational research. IZA Discussion Paper No. 5287.

Clements, M., & Seidman, E. (2002). The ecology of middle grades schools and possible selves: Theory, research, and action. In T. M. Brinthaupt & R. P. Lipka (Eds.), Understanding early adolescent self and identity: Applications and interventions (pp. 133–164). Albany: SUNY Press.

Collins, L. M., Schafer, J. L., & Kam, C. M. (2001). A comparison of inclusive and restrictive strategies in modern missing data procedures. Psychological Methods, 6(4), 330.

Denault, A. S., & Poulin, F. (2009). Intensity and breadth of participation in organized activities during the adolescent years: Multiple associations with youth outcomes. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38(9), 1199–1213.

DiPrete, T. A., & Buchmann, C. (2013). The rise of women: The growing gender gap in education and what it means for American schools. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Dornbusch, S. M., Mont-Reynaud, R., Ritter, P. L., Chen, Z. Y., & Steinberg, L. (1991). Stressful events and their correlates among adolescents of diverse backgrounds. In M. E. Colten & S. Gore (Eds.), Adolescent stress: Causes and consequences (pp. 111–130). New York: Aldine de Gruyter.

Eccles, J. S., & Barber, B. L. (1999). Student council, volunteering, basketball, or marching band: What kind of extracurricular involvement matters? Journal of Adolescent Research, 14(1), 10–43.

Eccles, J. S., Barber, B. L., Stone, M., & Hunt, J. (2003). Extracurricular activities and adolescent development. Journal of social issues, 59(4), 865–889.

Eccles, J. S., & Midgley, C. (1989). Stage-environment fit: Developmentally appropriate classrooms for young adolescents. Research on motivation in education, 3, 139–186.

Eccles, J. S., & Roeser, R. W. (2011). Schools as developmental contexts during adolescence. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 21(1), 225–241.

Editorial Projects in Education Research Center. (2012). Diplomas count 2012: Trailing behind, moving forward. Retrieved from http://www.edweek.org/ew/dc/

Eirich, G. M. (2012). Parental religiosity and children’s educational attainment in the United States. Research in the Sociology of Work, 23, 153–181.

Erikson, E. H. (1968). Identity: Youth and crisis (No. 7). New York: WW Norton & Company.

Espinoza, G., & Juvonen, J. (2011). Perceptions of the school social context across the transition to middle school: Heightened sensitivity among Latino students? Journal of Educational Psychology, 103(3), 749.

Feldman, A. F., & Matjasko, J. L. (2005). The role of school-based extracurricular activities in adolescent development: A comprehensive review and future directions. Review of educational research, 75(2), 159–210.

Fredricks, J. A. (2012). Extracurricular participation and academic outcomes: Testing the over-scheduling hypothesis. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 41(3), 295–306.

Fredricks, J. A., & Eccles, J. S. (2006). Is extracurricular participation associated with beneficial outcomes? Concurrent and longitudinal relations. Developmental Psychology, 42(4), 698.

Gallimore, R., Goldenberg, C. N., & Weisner, T. S. (1993). The social construction and subjective reality of activity settings: Implications for community psychology. American Journal of Community Psychology, 21(4), 537–560.

Giles, D. E, Jr, & Eyler, J. (1994). The impact of a college community service laboratory on students’ personal, social, and cognitive outcomes. Journal of Adolescence, 17(4), 327–339.

Graham, J. W. (2009). Missing data analysis: Making it work in the real world. Annual Review of Psychology, 60, 549–576.

Guest, A., & Schneider, B. (2003). Adolescents’ extracurricular participation in context: The mediating effects of schools, communities, and identity. Sociology of Education, 76(2), 89–109.

Hill, C. J., Bloom, H. S., Black, A. R., & Lipsey, M. W. (2008). Empirical benchmarks for interpreting effect sizes in research. Child Development Perspectives, 2(3), 172–177.

Kalechstein, A. D., & Nowicki, S, Jr. (1997). A meta-analytic examination of the relationship between control expectancies and academic achievement: An 11-yr follow-up to Findley and Cooper. Genetic, Social, and General Psychology Monographs, 123, 27–56.

Kieffer, M. J., & Marinell, W. H. (2012). Navigating the middle grades : Evidence from New York city. New York, NY: The Research Alliance for New York City Schools.

Knifsend, C. A., & Graham, S. (2012). Too much of a good thing? How breadth of extracurricular participation relates to school-related affect and academic outcomes during adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 41(3), 379–389.

Larson, R., Hansen, D., & Walker, K. (2005). Everybody’s gotta give: Development of initiative and teamwork within a youth program. Organized activities as contexts of development: Extracurricular activities, after-school and community programs, 159–183.

Markstrom, C. A. (1999). Religious involvement and adolescent psychosocial development. Journal of Adolescence, 22(2), 205–221.

Marsh, H. W., & Kleitman, S. (2002). Extracurricular school activities: The good, the bad, and the non-linear. Harvard Educational Review, 72, 464–514.

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998–2012). Mplus user’s guide (7th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén.

O’Donnell, C. R., & Tharp, R. G. (2012). Integrating cultural community psychology: Activity settings and the shared meanings of intersubjectivity. American Journal of Community Psychology, 49(1), 22–30.

Peck, S. C., Roesner, R. W., Zarrett, N., & Eccles, J. S. (2008). Exploring the roles of extracurricular activity quantity and quality in the educational resilience of vulnerable adolescents: Variable- and pattern-centered approaches. Journal of Social Issues, 64, 135–155.

Pedersen, S., Seidman, E., Yoshikawa, H., Rivera, A. C., Allen, L., & Aber, J. L. (2005). Contextual competence: Multiple manifestations among urban adolescents. American Journal of Community Psychology, 35(1–2), 65–82.

Peterson-Lewis, S. R., & Bratton, L. M. (2004). Perceptions of ‘Acting Black’ among African American teens: Implications of racial dramaturgy for academic and social achievement. Urban Review, 36(2), 81–100.

Rasberry, C. N., Lee, S. M., Robin, L., Laris, B. A., Russell, L. A., Coyle, K. K., & Nihiser, A. J. (2011). The association between school-based physical activity, including physical education, and academic performance: A systematic review of the literature. Preventive Medicine, 52, S10–S20.

Regnerus, M. D., & Elder, G. H, Jr. (2003). Staying on track in school: Religious influences in high- and low-risk settings. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 42, 633–649.

Rockoff, J. E. (2004). The impact of individual teachers on student achievement: Evidence from panel data. American Economic Review, 94(2), 247–252.

Rockoff, J. E., & Lockwood, B. B. (2010). Stuck in the middle: Impacts of grade configuration in public schools. Journal of Public Economics, 94(11), 1051–1061.

Roderick, M. (1994). School transitions and school dropout. In K. Wong (Ed.), Advances in Educational Policy (pp. 135–185). CT: JAI.

Rose-Krasnor, L., Busseri, M. A., Willoughby, T., & Chalmers, H. (2006). Breadth and intensity of youth activity involvement as contexts for positive development. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 35(3), 365–379.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2009). Promoting self-determined school engagement: Motivation, learning, and well-being. In K. Wentzel & A. Wigfield (Eds.), Handbook on motivation at school (pp. 171–196) . New York: Taylor Francis.

Seidman, E. (1991). Growing up the hard way: Pathways of urban adolescents. American Journal of Community Psychology, 19, 173–205.

Simmons, R. G., Black, A., & Zhou, Y. (1991). African-American versus White children and the transition to junior high school. American Journal of Education, 99, 481–520.

StataCorp. (2013). Stata Statistical Software: Release 13. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP.

Swanson, C. B. (2009). Closing the graduation gap: Education and economic conditions in America’s largest cities. Bethesda, MD: Editorial Projects in Education.

Vygotsky, L. (1981). Learning through interaction: The study of language development. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wachs, T. D. (1996). Known and potential processes underlying developmental trajectories in childhood and adolescence. Developmental Psychology, 32, 796–801.

Youniss, J., Mclellan, J. A., Su, Y., & Yates, M. (1999). The role of community service in identity development normative, unconventional, and deviant orientations. Journal of Adolescent Research, 14(2), 248–261.

Zimmerman, M. A., Caldwell, C. H., & Bernat, D. H. (2002). Discrepancy between self-report and school-record grade point average: Correlates with psychosocial outcome among African American adolescents. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 32(1), 86–109.

Acknowledgments

This research is supported in part by Grants from the National Institute of Mental Health (MH43084) and the Carnegie Corporation (B4850) awarded to Edward Seidman, J. Lawrence Aber, LaRue Allen, and Christina Mitchell. We would like to express our appreciation to the children and schools whose cooperation made this study possible.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Schwartz, K., Cappella, E. & Seidman, E. Extracurricular Participation and Course Performance in the Middle Grades: A Study of Low-Income, Urban Youth. Am J Community Psychol 56, 307–320 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-015-9752-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-015-9752-9