Abstract

A number of studies have demonstrated the efficacy of environmental change strategies (ECS) in effecting community-level change on attitudes and behaviors related to underage drinking (Treno and Lee in Alcohol Res Health 26:35–40, 2002; Birckmayer et al. in J Drug Educ 34(2):121–153, 2004). Primary data collection to inform the design of these strategies, however, can be resource intensive and exceed the capacity of community stakeholders. This study describes the participatory planning and implementation of community-level surveys in 12 diverse communities in the state of Washington. These surveys were conducted through collaborations among community volunteers and evaluation experts assigned to each community. The surveys were driven by communities’ prevention planning needs and interests; constructed from collections of existing, field-tested items and scales; implemented by community members; analyzed by evaluation staff; and used in the design of ECS by community-level leaders and prevention practitioners. The communities varied in the content of their surveys, in their sampling approaches and in their data collection methods. Although these surveys were not conducted using traditional rigorous population survey methodology, they were done within limited resources, and the participatory nature of these activities strengthened the communities’ commitment to using their results in the planning of their environmental change strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

A number of studies have demonstrated the efficacy of community-based environmental change strategies (ECS) focusing on intervening variables (e.g., youth access to alcohol) and consequences (e.g., drinking and driving) related to underage drinking (Treno and Lee 2002). Studies of efforts to enforce alcohol policies, for example, provide strong support for such interventions, while interventions to change community norms and social availability of alcohol rely on a thinner evidentiary base (Birckmayer et al. 2004). Primary data collection for the evaluation of community-wide or population-based prevention strategies can be resource-intensive and present methodological challenges. While gaps in intervention research related to ECS remain, even fewer examples of local-level data collection and evaluation for ECS are available.

In 2004 the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) Center for Substance Abuse Prevention (CSAP) announced funding for a new grant program, the Strategic Prevention Framework (SPF) State Incentive Grant (SIG). The SPF SIG program funded states to support data-driven planning and implementation of evidence-based practices at the community level to prevent and reduce substance abuse and related behaviors. From the beginning of the program, CSAP encouraged grantees to implement ECS in addition to direct service programs delivered to individuals and families. Cross-site workgroups of SPF SIG grantees and evaluators were convened to discuss grantee needs in a variety of areas. One of these workgroups was dedicated to ECS and developed a compendium of known ECS, their implementation guidelines and evidence base.

Washington State was in the first cohort of grantees to receive SPF SIG funding in 2004. Through an epidemiological analysis, the state selected underage drinking as its prevention priority and targeted those communities historically evidencing the highest rates of underage drinking. Among a pool of 48 eligible communities, the state randomly selected 12 communities for SPF SIG funding, stratified by population density, poverty, and racial/ethnic minority concentration. The SPF SIG intervention communities developed strategic prevention plans and logic models that included a mix of curriculum-based programs and environmental change strategies. Notably, the communities were directed by the state to include at least one ECS in their array of planned programs and strategies.

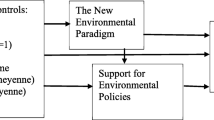

As part of the needs assessment and strategic planning process, the 12 Washington communities developed theory of change models that specified linkages between community needs, locally relevant intervening variables and contributing factors related to underage drinking. Every SPF SIG community identified at least one contributing factor related to community or parent norms, attitudes, or beliefs even though there was little or no empirical data to support their claim. For example, one community used student survey data to identify easy social access to alcohol as a key intervening variable and theorized that lack of parental monitoring was a contributing factor. Another community theorized that adult attitudes and beliefs that alcohol use is a rite of passage for teenagers was a contributor to easy social access. A third community that used archival indicators and student survey data to identify enforcement issues as an intervening variable theorized that lack of community or parent support for enforcement of underage drinking laws severely compromised the ability of officers to enforce underage drinking laws. Figure 1 illustrates examples of contributing factors theorized by communities to influence an intervening variable (lack of enforcement) related to underage drinking.

To confirm or refute these hypothetical relationships, the state directed SPF SIG communities to implement community surveys to assess adult attitudes and beliefs related to underage drinking. A related and explicit intent of the surveys was to provide data that could be used to inform ECS efforts, in particular social marketing and communication campaigns. For communities targeting enforcement, the surveys were intended to identify normative beliefs in the community that might be barriers to implementation of ECS directed at law enforcement or policy. The community surveys would also serve as an indicator of change over time in these attitudes and beliefs, through a second administration 2 years following the initial survey.

All 12 SPF SIG communities conducted their surveys through the collaboration of local volunteers, organizational representatives and SPF SIG evaluators, exemplifying the key principles of community-based participatory research (Minkler and Wallerstein 2003). The community-level evaluators were a diverse group of professionals from a private research firm contracted by the state to conduct the state and local SPF SIG evaluation. Their educational training ranged from Bachelor’s to Ph.D. degrees. They were diverse in their skill sets but, as a team, included strong expertise in survey research, quantitative analysis, qualitative design and analysis, psychometrics, and prevention theory. Their most common trait, and perhaps most important to the lead evaluator, was that they all had at least 12 years’ experience in applied, field-based evaluation in substance abuse prevention and related areas. While each of the 12 SPF SIG communities was assigned a single evaluator, they functioned as a team, bringing their individual methodological strengths to evaluation planning and implementation issues that emerged at any site. Over the course of the project, each built a strong relationship and worked closely with the SPF SIG director in their assigned communities.

In these community survey efforts, the evaluators assembled a compendium of field-tested items and scales from existing prevention literature, facilitated local workgroups in the construction of the instrument, guided survey administration processes, analyzed resultant data, and guided the interpretation and reporting of results to community groups. SPF SIG directors and coalition members brought their in-depth knowledge of the culture and capacity of their community to finalizing the survey instrument, organizing, and bringing needed resources to the administration of the survey, monitoring survey returns, identifying key audiences for reporting of survey results, and often participating in those presentations. As suggested by Fawcett et al. (1996), the process was empowering to the communities, in that it respected their knowledge of their own communities, it injected research expertise in the design and analysis of the surveys and, perhaps most importantly, it enhanced the relevance of and commitment to the resultant data in the planning and implementation of communities’ environmental change strategies.

Method

Focused on their own local prevention planning, several characteristics of the community survey efforts differed across the 12 SPF SIG communities, including their intended target populations, data collection methods, survey content, and administrative procedures.

Participants

Participants in the survey were a consequence of the target population and data collection methods selected by each community. Depending upon the intended recipients of prevention services and environmental change strategies, communities selected either all adults in the community or only those who were parents with children enrolled in the local school system. As the SPF SIG project developed further, many communities that had originally targeted all adults in their community shifted their focus in 2010 to parents of school children in their community.

Once their target populations were determined, local evaluators assisted community practitioners in constructing lists of population members and location information. Communities attempted either a census or random sampling approach in the administration of their surveys. However, those employing an intercept sampling approach were essentially attempting to maximize their sample size by collecting their data at times and locations known to attract sizable portions of their target population.

As shown in Table 1, community-level survey sample sizes ranged from 260 to 600 in 2008; and totaled over 3,500 adults in all. Sample sizes were generally slightly lower in 2010. The 2010 survey administration occurred at the end of the grant, when coalition efforts were directed toward close-out activities and sustainability and local evaluator resources were diminished.

Data Collection Methods

Four distinct data collection methods, or their combinations, were employed by the communities in the administration of their surveys in 2008: mail, on-line, intercept, and personal interview. In 2008 the majority of the communities administered their surveys by mail and included a targeted follow-up to increase response rate, some going to on-line or intercept methods to increase the efficiency of data collection. All three urban communities targeted parents of school children as their target population, and administered their surveys via on-line mechanisms. Two of the three communities characterized by high racial/ethnic minority populations chose to administer their surveys in person at strategically selected times and locations to maximize their response rate, using methodology originally known as mall intercept sampling (Bush and Hair 1985) and more recently generalized to location-based sampling (Sudman and Blair 1999). Finally, one community elected to add these survey items to an ongoing household survey it was conducting for other purposes, and obtained its responses through personal interviews.

Data collection methods changed somewhat in 2010, partly based on the communities sharing experiences and lessons learned from their 2008 survey efforts. Four communities abandoned their mailed surveys, shifting to either intercept or on-line data collection; and the community that combined this survey with an ongoing household survey had no such coincidence in 2010 and shifted to an intercept survey.

Measures

As noted earlier, the content of the community surveys was driven by each community’s need for data and information to substantiate aspects of their local logic models and to inform their environmental change strategies. These strategies ranged from social marketing and social norms marketing campaigns that relied heavily on disseminating prevention-focused messages through various media; to those directed at policy or regulatory change pertaining to alcohol use in the community and related enforcement concerns.

These variations notwithstanding, a number of constructs were commonly used across many of the 12 communities. Prominent examples of these were:

-

Attitudes, beliefs and behaviors related to underage drinking—all 12 communities included questions relating to these;

-

Perceptions of these attitudes, beliefs and behaviors in the community as a whole—7 of the 12 communities included these questions;

-

Attitudes about the enforcement of alcohol laws and regulations—eight communities;

-

Perceptions of the legal consequences of underage drinking—seven communities.

Surveys ranged from 20 to 40 items in length across the communities. Items or scales comprising these instruments were selected from a compendium of field-tested instruments identified by the local evaluators working in each community. The most frequently tapped surveys from the compendium were the Minnesota Community Readiness Survey (Beebe et al. 2001); the Montana Most of Us Social Norms Parent Survey (Montana State University 2000); and the Project Northland program surveys (Perry et al. 2000).

Procedures

The first round of community survey data collection was conducted in spring 2008. Community volunteers and coalition members first identified the domains or constructs of interest. Typically, these were elements of their local theory of change models guiding their SPF SIG prevention efforts. After these were identified, local evaluators assembled items and scales from the instrument compendium and reviewed them along with local community members for inclusion on the survey. The three communities with high racial/ethnic minority concentrations (primarily Hispanic) translated their surveys into Spanish to facilitate participation of their Hispanic populations in the survey effort. Once the content and translation of the surveys were finalized, the administration of the surveys commenced. Communities reported their response rates to local evaluators within three to 4 weeks of initial administration, with particular attention paid to the demographics of the sample in relation to those of the intended target population. Follow-up survey activities were undertaken in all communities to augment the sample size and improve representativeness of the respondent sample. Data collection lasted for 2 months, and local evaluators provided descriptive analyses of the relevant items and interpretive guidelines for local community members, as they moved to the data-based design of their environmental change strategies.

Results

Since the content of the community surveys was designed to address each community’s information needs in planning their prevention programs and environmental change strategies, results presented here are in the form of a synthesis of general themes that emerged, along with specific illustrations used to drive ECS in several SPF SIG communities.

A Synthesis of General Findings from the Community Surveys

As noted earlier, several general constructs were included in community surveys with sufficient frequency to use as illustrations of how these data were used to drive ECS planning across multiple communities: adults’ attitudes and beliefs about underage drinking; their perceptions of the attitudes, beliefs and behaviors of other adults in the community related to underage drinking; and their attitudes toward enforcement of existing laws and regulations on underage drinking.

Attitudes and Beliefs About Underage Drinking

Although the specific items used in communities’ surveys varied, all 12 SPF SIG communities included questions assessing adults’ views about underage drinking. The most pervasive finding in these surveys was that the vast majority of adults and parents did not report permissive attitudes toward underage drinking under virtually any circumstances. Selected findings included:

-

Across four communities, 63–76 of adults strongly disagreed that it is “OK for teenagers/underage youth to drink at parties as long as they don’t get drunk.”

-

In another four communities, 89–92 % of parents of school-aged children disagreed or strongly disagreed that it is “OK for 18–20 year olds to drink alcohol.”

-

In two communities, 82–90 % of parents agreed or strongly agreed that it is “never OK to offer your underage children alcohol in your home.”

Perceived Attitudes and Behaviors of Other Adults in the Community About Underage Drinking

To explore whether a social norms marketing campaign was warranted, seven communities included items asking respondents how they thought other adults or parents in their community felt about these issues. There was a persistent and significant gap between adults or parents reports of their own attitudes and behaviors related to underage drinking and their perceptions of how their fellow adults or parents in the community felt about these issues. For example:

-

In one community characterized by high poverty and high racial/ethnic minority population, virtually all parents (92 %) disagreed or strongly disagreed that it was OK for 18–20 year olds to drink alcohol, but only 78 % agreed or strongly agreed that “most adults” in the community felt the same way.

-

In another rural, primarily Caucasian community, while 94 % of the parents reported that they had explained the rules about alcohol use to their children, only 52 % report believed that the “typical parent” in their community had done the same.

-

Similarly, in another rural community with a large Hispanic population, 80 % of the parents reported communicating nonpermissive messages about alcohol use to their children in the past 3 months, but only 38 % reported they believed the “typical family” had done the same.

Attitudes Toward the Enforcement of Underage Drinking Laws and Regulations

In the development of their prevention program logic models, several communities voiced concerns about the lack of consistent enforcement of underage drinking laws by the law enforcement and justice sectors in the community. Often, these concerns were met with the response that, if such enforcement were strengthened, most adults in the community would not be supportive, citing traditional rite of passage points of view in relation to underage drinking. To address these concerns empirically, eight of the SPF SIG communities included items on their surveys assessing community attitudes toward the enforcement of underage drinking laws and regulations. Results indicated that, in general, parents and adults in these communities were very supportive of enforcement efforts. Selected findings included:

-

In a community characterized by high racial/ethnic minority populations, 75 % of parents strongly agreed that “police should break up parties when youth are using alcohol or drugs.”

-

In a tribal community, nearly two-thirds (64 %) of adults strongly agreed that “police should enforce tribal laws against underage drinking.”

-

In three other communities, characterized by high Caucasian populations, about two-thirds of parents and adults strongly agreed that police should break up underage youth parties in people’s homes (62 and 67 %) or in outdoor locations (69 %) when youth are drinking.

Relatedly, respondents to these surveys in three communities reported less certainty that law enforcement was committed or effective in their enforcement efforts of underage drinking laws and regulations. For example:

-

In two rural communities, fewer than 1 in 4 of the parents and adults (15 and 23 %) strongly agreed that law enforcement was “committed” and less than 20 % of them strongly agreed that law enforcement responded effectively to underage drinking violations.

-

In another rural community, only about 1 in 5 adults (21 %) strongly agreed that schools effectively enforce school policies on alcohol and other drug use.

-

In a fourth community with substantial representation of Hispanic and American Indian families, only about 1 in 3 adults (35 %) believed that underage drinking laws were enforced at all.

Representativeness of Findings to Intended Target Population in the Community

The highly participatory nature of these community survey efforts was accompanied by insufficient resources to do a scientifically rigorous sampling of their intended populations. Still, the representativeness of the respondent samples was a prominent concern in the interpretation of results. Representativeness was assessed in relation to known demographic characteristics of the communities’ target populations, either all adults in the community (2010 US Census data) or parents of youth enrolled in its schools (school district records).

In Table 2, the proportions of respondents categorized by gender, race and age group are provided for all 12 communities. Since target populations varied across communities (and within communities across time, in some cases), the corresponding target population data are not provided. Even in the absence of precise statistical comparisons, several discrepancies are apparent.

Gender

There is a clear over-representation of female adults in these samples. In 9 of the 12 communities in 2008, females comprised more than 60 % of the respondent samples. In 3 of the 12 communities, females constituted 80 % or more of the sample. This disproportionality is associated with the data collection method employed. For example, in 2008 the two communities that used on-line data collection exclusively had 69 and 75 % female respondents respectively.

Race/Ethnicity

Two of the three communities in the “high racial/ethnic minority” cluster under-represented their minority populations in their respondent sample in 2008 at 24, and 41 %, respectively. These communities focused efforts on improving this representation in 2010 and were quite successful, increasing to 48 and 79 %, respectively. Two of the three urban SPF SIG communities also had sizable racial/ethnic minority populations. Respondent samples from both of these urban communities were reasonably representative of their cultural diversity in 2008. Finally, both American Indian communities were very successful in their representation in both years.

Age Group

Direct comparisons between the age of respondents and that of the target populations across communities are problematic for two reasons. First, the target population for the surveys in many communities was parents of middle and high school-aged youth; and demographic data were not readily available on this segment of the community as a whole. Secondly, the community surveys were not consistent in the age categories represented on the survey instruments. These limitations notwithstanding, it still seems clear that older adults were over-represented in most SPF SIG communities. For example, of the seven communities using a category of “45 or older” in their surveys in 2008, about two-thirds (66.4 %) of the respondent sample were in this age group. US Census data from 2010 indicated that 39.4 % of Washington’s citizens are in this age group. Only three communities’ samples were within 10 % of their target population representation in this older category. Again, this was associated with data collection method. All three of these communities used either intercept or household interview data collection methods in 2008.

Impact of Nonrepresentativeness on Survey Estimates in Planning ECS

In general, respondent samples in the SPF SIG community surveys in 2008 over-represented females and older adults in their target populations. In communities with high proportions of racial/ethnic minorities, there was also an under-representation of minorities, primarily Hispanic adults and parents. While representative samples are the goal of any population survey effort, it has specific and concrete implications for ECS. Data-based messages in a social marketing or social norms marketing strategies must be characteristic of the population in which the campaign is conducted. For example, it would be erroneous to say that 92 % of the community does not condone underage drinking under any circumstances if this estimate was driven by an over-represented segment of the community known to oppose these behaviors more vehemently than others.

Differences in ECS-relevant survey items between the demographic groups displayed in Table 2 were calculated in each of the communities for which disproportionate representation occurred. Illustrative results are shown in Table 3.

Attitudes Toward Underage Drinking

As noted earlier, all SPF SIG communities included questions about adults’ or parents’ attitudes toward underage drinking. Survey results indicated that men consistently reported more permissive attitudes toward underage drinking than women. Gender-based prevalence rates from four communities that used highly comparable questions representing this general construct are shown in Table 3. In general, 15–20 % more women than men do not condone underage drinking under any circumstances. A similar percentage of women feel more strongly against parents offering alcohol to their children at home than do men in the respondent samples. This would suggest that the percentage of adults in these communities strongly disapproving of underage drinking (reported earlier as 80–90 % in the aggregate) may be slightly overstated based on these gender differences and the over-representation of females in the respondent samples. However, even modifying the prevalence rates previously reported, it was still clear that the vast majority of adults in SPF SIG communities disapprove of underage drinking under any circumstances.

In relation to race/ethnicity, it was also noted in Table 2 that several communities with culturally diverse populations (6 of the 12 SPF SIG communities) overrepresented Caucasians in their survey respondents in 2008. While this disparity was remedied to a large degree in the 2010 survey, the 2008 survey results were those used for ECS planning and, at face value, were not sufficiently representative of racial/ethnic minorities. In general, racial/ethnic minority respondents reported more tolerant or permissive attitudes toward underage drinking than did Caucasians in three of these communities, as shown in Table 3. Interestingly, however, in the five culturally diverse communities in which respondents were asked about the specific practice of parents offering alcohol to their children, 10–25 % of the Caucasian adults reported more permissive attitudes than did minority respondents in these communities.

Attitudes Toward Enforcement of Underage Drinking Laws and Regulations

In three of the SPF SIG communities, the disproportionality of women respondents was also associated with significant differences in their attitudes toward enforcement. In general, women felt more strongly that underage drinking laws and regulations should be consistently enforced. In terms of race/ethnicity, minority respondents in results were mixed across three highly diverse SPF SIG communities. In two of the communities, racial/ethnic minorities were more strongly supportive toward the consistent enforcement of these laws and regulations than were Caucasians; but in a third, racial/ethnic minorities were less supportive.

Use of Community Survey Findings in Design of ECS

As noted earlier, all 12 SPF SIG communities planned and implemented at least one ECS. Survey findings drove the design of social norms marketing campaigns in seven communities. Three other communities used survey findings to formulate or bolster efforts to strengthen underage drinking laws and regulations and their enforcement, including collaborative activity to improve consistency and effectiveness of law enforcement response. Examples are provided here to illustrate data-driven ECS planning in both of these areas.

Social Norms Marketing

Social norms campaigns are rooted in the theory that using data to correct misperceptions of norms can induce a greater proportion of the population to act in accordance with the true norms (e.g., against underage drinking; Perkins, 2003). Washington SPF SIG communities that implemented social norms campaigns generally publicized community survey findings that the majority of parents in the community used recommended parental monitoring practices featuring consistent communication around alcohol use. Examples included:

-

The prevention coalition in a small agricultural community in central Washington launched the It’s a Fact campaign, conveying messages such as, “8 out of 10 ___________ [community name] parents talk to their kids about not drinking alcohol.”

-

Another rural community implemented a Congratulations campaign, with messages such as “Congratulations ____________ [community name] Parents: 9 out of 10 of you know where your kids are;” and “Congratulations ____________ [community name] Parents: 9 out of 10 of you have rules against underage drinking.”

-

A nonurban former timber industry community found that community survey results on parent communication were remarkably consistent with responses to similar items on a local student survey. The community created campaign messages that referenced both surveys, for example, “_____________ [Community name] kids and parents agree: 7 out of 10 parents talk to their kids about not using alcohol.”

-

A community in northern Washington with a sizeable Hispanic/Latino population created links between the social norms campaign messages and a parent networking strategy to encourage parent communication and support. Campaign materials displayed both a social norms message (e.g., “Most ____________ [community name] Parents… Contact, Confirm, Connect”) and included further information on participating in parent network activities.

In designing social norms campaigns, SPF SIG communities received technical assistance from the state’s technical assistance consultants, used focus group message-testing, and in some cases conducted periodic intercept surveys to gather information about the reach, recall, and reactions to the campaign messages. The communities used locally relevant distribution channels such as ads in high school football schedules and on buses, posters displayed in medical offices and school buildings, messages to school district parents through postcard mailings and back-to-school packets, mall displays, and traditional media such as local radio and billboards. One community used social media as well. Communities with large Hispanic/Latino populations disseminated messages in both English and Spanish. One SPF SIG community with a large Hispanic/Latino population used formative data from intercept surveys collected during the campaign to better target locations for Spanish-language campaign messages, shifting from billboards to greater investment in advertisements on buses.

Strengthening and Enforcing Underage Drinking Laws and Regulations

Concerned about the enforcement of underage drinking laws and regulations, several SPF SIG communities engaged representatives of local and/or county law enforcement and justice in discussions of their concerns. Over time, this grew to consistent (and often unprecedented) participation of law enforcement and justice personnel on their community prevention coalitions. In one urban community, they initiated a Law Enforcement Roundtable, scheduling periodic public discussions about the status and progress of enforcement and penalties related to underage drinking incidents and patterns in the community. In another highly rural community, characterized by generations of youth drinking in wooded areas and forest preserves in the surrounding area, law enforcement professionals gradually became regular participants in coalition meetings, and a “law enforcement update” evolved as a standing agenda item. Finally, in an American Indian community located in a highly rural area that also included a large Hispanic/Latino population, a law enforcement committee was established, comprised of county police, state police and tribal police–the first known formal collaboration of these law enforcement entities in this area.

In another American Indian community, the tribal prevention coalition was committed to strengthening its codes and laws related to alcohol and other drug use, as they had not been reviewed or amended since the 1980s. In developing its SPF SIG logic model, the coalition included concerns for ambiguities in the current code and inconsistency of tribal enforcement practices as contributing factors to the high rates of underage drinking in the community.

In 2008, the tribal coalition conducted a door-to-door survey on the reservation that included a number of questions relating to adult attitudes, beliefs and behaviors related to youth alcohol use. Survey results indicated that nearly half the adult population (46 %) strongly agreed that the tribal police should enforce tribal laws against underage drinking, specifically breaking up teen parties in homes or outdoor locations where youth are drinking. Further, over 40 % strongly agreed that tribal courts should impose strong consequences when teens are caught drinking. When asked about the status of current enforcement, over one-third (36 %) of the adults disagreed or strongly disagreed that the police were “committed to enforcing laws” pertaining to underage drinking; and nearly half (48 %) disagreed or strongly disagreed that police “effectively respond to calls and request” about this.

A coalition subcommittee was formed, including representatives from the tribal police and courts. Numerous changes were made over a year’s meetings featuring the creation of zero tolerance policies relating to underage drinking and adults hosting parties with alcohol; and the initiation of youth classifications for offenses rather than using adult classifications for youth offenses. In addition, a social marketing campaign emphasizing the zero tolerance policy–Take Back the Rez–was initiated and subsequently used by tribal law enforcement as the backbone of their increased enforcement efforts. Concurrently, the coalition worked with the tribal police in the development of a Tribal Tip Line that allowed community members to confidentially inform the police about suspicious criminal activity. In the first 6 months there were over 400 calls to the tip line.

Discussion

These collaborative and highly participatory community survey activities produced a number of community-specific learnings that informed the planning and implementation of their prevention programs and strategies. Because community members were integrally involved in the data collection, the resultant data had the credibility with them that an externally-driven survey would not have. In some cases, the findings of the survey contradicted conventional wisdom about community attitudes toward underage drinking. For example, many community coalitions felt there was a lax and permissive attitude among most adults that teen alcohol use was a rite of passage; or that, while youth drinking was not condoned, as long as they did not drive while intoxicated, it was not as serious of an issue. Or, in the company of their parents at home, it was permissible for youth to drink. All of these perceptions were contraindicated by survey data in these communities.

While initially conceived to inform the planning and implementation of prevention strategies, the community surveys had implications for evaluation as well. Because communities hoped to effect change in contributing factor prevalence rates, the community surveys provided a means of assessing potential change. Anticipated evaluation needs influenced the design of the survey instruments, including the selection of items and administration approaches.

However, while communities’ interest in and commitment to these results was strong, these survey efforts were not without their imperfections. Social desirability response bias is always an issue with value-laden survey items, though precautions to ensure respondent anonymity were taken and no individual identifiers were included in the survey. As noted, respondent samples were typically not adequately representative of the full community. However, even these flaws resulted in important local learning and capacity building. For example it was clear that, to some extent, the lack of community representativeness in respondent samples was associated with the target population specified or the data collection method employed. Mailed surveys were particularly prone to over-representing older adults while on-line surveys typically over-represented females. When parents of school children were the target population, mothers were more frequently listed on school district mailing lists than were fathers and, consequently, females were overrepresented in these survey results.

In addition to the methodology employed, stratified analyses of survey results by community evaluators added to the understanding of attitudes among specific demographic groups in the community and, in some instances, contradicted stereotypical beliefs. For example, in several culturally diverse communities, differences between racial/ethnic groups on their attitudes toward youth drinking were rather small; but the gap between self-reported attitudes and behaviors and perceptions of those of other adults in the community was very different along racial/ethnic lines. In one of the predominantly Caucasian communities, contrary to popular belief, people at different income levels did not differ in their support for underage drinking laws.

In the use of community survey results to drive environmental change strategies, the obtained prevalence rates of attitudes or perceptual gaps in attitudes were not statistically adjusted or modified based on the demographic representation in the respondent samples. For example, prevalence rates of women’s attitudes were not weighted less than those of men to compensate for the under-representation of the latter in coming up with a community-wide prevalence rate, despite some attitudinal differences by demographic group (see Table 3). In crafting media messages based on community attitudes, SPF SIG communities instead tended to focus on attitudes that held true across demographic groups. For example, while women were more likely to report strongly disapproving of underage drinking, men and women generally disapproved of underage drinking at similar rates. In some cases SPF SIG communities also adjusted their ECS dissemination activities to specifically reach under- or over-represented groups from the survey results.

Inconsistencies in survey methodology between 2008 and 2010 administrations precluded use of these data for ECS outcome evaluation in most communities. These changes in target population or survey content (see Table 1) were neither capricious nor arbitrary, however. Rather, they reflected shifts in the focus of environmental change strategies or the need for new information driven by other prevention activities or community needs that had emerged. While these changes were responsive and appropriate from the SPF SIG data-driven planning perspective, they obviously compromised communities’ ability to use the 2010 surveys as instruments for ECS outcome evaluation.

In a very real sense, the lack of financial resources drove the cooperative planning and participatory nature of these community survey efforts. Within their local SPF SIG budgets, communities were limited to spending $5,000 on evaluation activities beyond those conducted by their local SPF SIG evaluator. To contract for the conduct of surveys of the scope and magnitude represented here using the more scientifically rigorous methodology of professional survey firms would have cost $20,000–$30,000 per community–well above their budget limitations. Across 12 SPF SIG communities, the $240,000–$360,000 required would have easily eclipsed the state’s entire SPF SIG evaluation budget.

In conclusion, Washington State SPF SIG communities’ administration of surveys of adults and parents proved a low cost and useful aspect of a comprehensive prevention planning, implementation and evaluation effort. The surveys were essential in informing the implementation of social marketing campaigns and in strengthening the enforcement of underage drinking laws. These surveys provided data for planning ECS that both supported and occasionally contradicted coalition members’ initial expectations about community norms.

Finally, perhaps the major benefit derived from these surveys was that ascribed to all successful applications of community-based participatory research (Cousins and Whitmore 1998; Minkler and Wallerstein 2003): Resultant data were the communities’ property. They collected it, they believed in it, and they relied on it in planning and implementing their environmental change strategies.

References

Beebe, T. J., Harrison, P. A., Sharma, A., & Hedger, S. (2001). The community readiness survey: Development and initial validation. Evaluation Review, 25(1), 55–71.

Birckmayer, J. D., Holder, H. D., Yacoubian, G. S., & Friend, K. B. (2004). A general causal model to guide alcohol, tobacco, and illicit drug prevention: Assessing the research evidence. Journal of Drug Education, 34(2), 121–153.

Bush, A. J., & Hair, J. F. (1985). An assessment of the mall intercept as a data collection method. Journal of Marketing Research, 22(2), 158–167.

Cousins, J. B., & Whitmore, E. (1998). Framing participatory evaluation. New Directions for Evaluation, 80, 5–23.

Fawcett, S. B., Paine-Andrews, A., Francisco, V. T., Schultz, J. A., et al. (1996). Empowering community health initiatives through evaluation. In D. M. Fetterman, S. J. Kaftarian, & A. Wandersman (Eds.), Empowerment evaluation: Knowledge and tools for self-assessment and accountability. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Minkler, M., & Wallerstein, N. (Eds.). (2003). Community-based participatory research for health. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Montana State University & Montana Department of Public Health & Human Services. (2000). Montana parent norms survey: Summary findings from a survey of Montana parenting behaviors and perceptions associated with teen substance use. Bozeman, MT: Author.

Perkins, H. W. (2003). The emergence and evolution of the social norms approach to substance abuse prevention. In H. W. Perkins (Ed.), The social norms approach to preventing school and college age substance abuse: A handbook for educators, counselors, and clinicians (pp. 3–17). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Perry, C. L., Williams, C. L., Komro, K. A., & Veblen-Mortenson, S. (2000). Project Northland: A community-wide approach to prevent young adolescent alcohol use. In W. B. Hansen, S. M. Giles, & M. D. Fearnow-Kenney (Eds.), Improving prevention effectiveness (pp. 225–234). Greensboro, NC: Tanglewood Research.

Sudman, S., & Blair, E. (1999). Sampling in the twenty-first century. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 27(2), 269–277.

Treno, A. J., & Lee, J. P. (2002). Approaching alcohol problems through local environmental interventions. Alcohol Research and Health, 26, 35–40.

US Census Bureau (2010). Age groups and sex 2010: Washington State. Retrieved February 1, 2012, from http://factfinder2.census.gov/faces/tableservices/-jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=DEC_10_SF1_QTP1&prodType=table.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gabriel, R.M., Leichtling, G.J., Bolan, M. et al. Using Community Surveys to Inform the Planning and Implementation of Environmental Change Strategies: Participatory Research in 12 Washington Communities. Am J Community Psychol 51, 243–253 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-012-9543-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-012-9543-5