Abstract

This study explores the multidimensional nature of religiosity on substance use among adolescents living in central Mexico. From a social capital perspective, this article investigates how external church attendance and internal religious importance interact to create differential pathways for adolescents, and how these pathways exert both risk and protective influences on Mexican youth. The data come from 506 self-identified Roman Catholic youth (ages 14–17) living in a semi-rural area in the central state of Guanajuato, Mexico, and attending alternative secondary schools. Findings indicate that adolescents who have higher church attendance coupled with higher religious importance have lower odds of using alcohol, while cigarette use is lower among adolescents who have lower church attendance and lower religious importance. Adolescents are most at risk using alcohol and cigarettes when church attendance is higher but religious importance is lower. In conclusion, incongruence between internal religious beliefs and external church attendance places Mexican youth at greater risk of alcohol and cigarette use. This study not only contributes to understandings of the impact of religiosity on substance use in Mexico, but highlights the importance of understanding religiosity as a multidimensional phenomenon which can lead to differential substance use patterns.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Mounting epidemiological data suggest that Mexican youth are using substances at similar rates as US youth (Borges et al. 2009; Marsiglia et al. 2009; Medina-Mora et al. 2006). Although historically, Mexican adolescents had lower rates of substance use compared to US youth, this gap is decreasing, and among Mexican youth, cigarette and alcohol use are on the rise (Arillo-Santillán et al. 2005; Benjet et al. 2007a, b; Bird et al. 2006; Lotrean et al. 2005; Medina-Mora et al. 2003; Ritterman et al. 2009; Villalobos and Rojas 2007). Recent prevalence rates estimate that 17% of Mexican youth are current cigarette smokers and 30% are current alcohol users (Ritterman et al. 2009). Like US youth, Mexican adolescents are also challenged with the same social and health problems associated with substance use such as school dropout, traffic fatalities, sexually transmitted diseases, and antisocial and criminal behavior (Latimer et al. 2004; Medina-Mora et al. 2003; Villatoro et al. 2004). Mexican youth in early adolescence who initiate use of substances are also at a higher risk for prolonged use throughout adolescence and into adulthood (Hawkins et al. 1997; Kuri-Morales et al. 2000; Wills et al. 2001; Wills et al. 2003).

Despite these rising rates, increased health problems, and prolonged social consequences, research on the social processes related to substance use among Mexican youth is limited. Specifically, there is a need for ongoing research as risk and protective factors influencing alcohol and other drug use among Mexican youth may change over time or across cohorts. Understanding risk and protective factors of substance use is imperative to promoting healthy development in adolescence (Ostaszewski and Zimmerman 2006). One area in need of further research is the role religion plays in Mexico (Wilson 2008), where the predominance of Roman Catholicism coupled with the country’s high rate of church attendance, around 50%, can serve as important social capital for many Mexicans (University of Michigan News and Information Services 1997; Wilson 2008). Religious salience in Mexico is also very high with 84% of Mexicans reporting that religion is very important or important, with only 3% claiming religion to have no meaning in their lives (Camp 2000). The Roman Catholic tradition has been described as a repository of culture among Mexicans and Mexicans Americans (Levin et al. 1996), and understanding religiosity in Mexico can have broader implications than in the US or in Western Europe because in these “moral communities”—that is, communities with high religiosity- religion can have both a direct and indirect effect on individuals’ behavior (Stark 1996; Stark and Bainbridge 1996). On the other hand, the predominance of Roman Catholicism in the religious and social lives of Mexicans makes studies about the effects of religiosity on health outcomes very different than the ones conducted with US-based samples usually presenting a plurality of religious affiliations (Benjamins and Buck 2009).

Although US research has consistently found religiosity to be a protective factor against substance use for US adolescents (Amey et al. 1996; Chatters 2000; Cochran and Akers 1989; Miller et al. 2000; Nonnemaker et al. 2003; Wallace and Forman 1998) by strengthening assets of adolescents (Scott et al. 2006), it is still not understood to what degree religiosity acts as a protective factor among Mexican youth—especially those living in a predominant Roman Catholic area. The targeted community in this study is in a region of Mexico with a one hundred year tradition of migration to the US. The results of the study have the potential of advancing knowledge not only about religiosity as a possible protective or risk factor in Mexico, but they can inform the design of health promotion interventions on both sides of the Mexico-US border. The present study aims at making a contribution in that direction from a social capital perspective. The overall hypothesis guiding the study is that Mexican youth residing in central Mexico who report stronger internal religiosity will report lower use rates of alcohol and cigarettes.

Religiosity and Drug Use From a Social Capital Perspective

Religiosity is most often thought to act as a protective factor for substance use because participation in religion provides social capital for individuals (Longest and Vaisey 2008). At the micro level, social capital is viewed as the tools and resources available to the individual which can be useful in achieving goals (Van der Gaag and Snijders 2004). “Specifically for adolescents, religion can serve as an additional normative structure providing positively guided sanctions as well as a location for fostering beneficial relationships that teach adolescents prosocial behaviors” (Longest and Vaisey 2008, p. 689). These resources and tools can exert a protective influence on adolescents through numerous pathways and across several domains of individual’s life (Van der Gaag and Snijders 2004): a highly religious community enhancing and supporting the adolescent’s individual beliefs and behaviors (Wallace et al. 2007); a network of adults providing additional monitoring of adolescent activities (Longest and Vaisey 2008; Smith 2003;Wills et al. 2004); a network of non-deviant peers guarding against opportunities to use drugs (Amoateng and Bahr 1986; Bahr et al. 1998; Longest and Vaisey 2008; Mason and Windle 2001; Oetting et al. 1998); a higher level of social support through frequent social contact (Strawbridge et al. 1997); a family with greater cohesion (Turner 1994); a parent exercising a higher level of monitoring (Li et al. 2000); and an overall social environment not tolerant of deviant behavior (Benjet et al. 2007; Hadaway et al. 1984). Each of these pathways promotes and reinforces participation in positive behaviors and activities while endorsing disengagement from negative behaviors and activities (Bahr et al. 1998; Longest and Vaisey 2008).

As a multidimensional phenomenon, the study of religiosity requires an examination of the different processes leading to differential behavior patterns and the meaning youth attach to their connection to religion (Longest and Vaisey 2008). There is a need to move beyond religion just as a form of social control over young people’s behavior and attitudes and to study religiosity as a form of social capital. The social capital perspective recognizes the multidimensional nature of religious commitment (Bartkowski and Xu 2007). At the individual-level, religiosity among adolescents and young adults is understood to have three components: (1) Exposure to and internalization of religious norms; (2) Integration within religious networks; and (3) Expressions of religious trust (Putman 2000; Baron et al. 2000; Bartkowski and Xu 2007). The present research focuses on the first component and studies the exposure of youth in central Mexico to religion and if religion becomes personally important for the adolescent in order to become protective against substance use (Longest and Vaisey 2008). In order to move beyond social control, the present examination focuses on the youth’s internal reaction to religion and spirituality as a possible asset or capital.

The Protective Effect of Religiosity

Religiosity often refers to both religious behaviors and religious attitudes (Amey et al. 1996). This multi-dimensional construct typically encompasses external religiosity (or public religiosity) and internal religiosity (or private religiosity) (Fiala et al. 2002; Nasim et al. 2006; Piko and Fitzpatrick 2004; Resnick et al. 2004; Van Den Bree et al. 2004). External religiosity refers to an individual’s participation and involvement in religious activities, such as church attendance, while internal religiosity refers to the importance an individual places on religion through personal behaviors, such as prayer (Fiala et al. 2002; Nasim et al. 2006).

The protective effect of religiosity has been demonstrated in various US-based studies. When religiosity is high, alcohol use (Amey et al. 1996; Cochran and Akers 1989; Miller et al. 2000; Wallace and Forman 1998) and cigarette use (Amey et al. 1996; Nonnemaker et al. 2003; Wallace and Forman 1998) are low. Furthermore, the protective nature of religiosity extends to racial and ethnic groups in the US (Amey et al. 1996; Marsiglia et al. 2005; Wallace 1999; Wallace et al. 2003; Wills et al. 2003). For African American adolescents religiosity was associated with fewer negative health behaviors including less substance use and risky sexual behaviors (Steinman and Zimmerman 2004; Wills et al. 2003). For Hispanic youth living in the US, religion was also protective against substance use (Marsiglia et al. 2005; Wallace 1999). When specifically examining Mexican and Mexican–American youth living in the southwestern US, religiosity was protective against both lifetime and recent cigarette and alcohol use (Marsiglia et al. 2005).

While there is much information regarding the protective influence of religiosity on substance use, it must not be forgotten that for adolescents the effects of religiosity can be confounded because they are under the authority of their parents and therefore many decisions about the adolescents’ religious affiliation and religious participation can be determined by their parents (Marsiglia et al. 2005). Religiosity, particularly external religiosity, may be more influenced by the parent’s religious participation than the adolescent’s individual expression of religiosity (Hodge et al. 2001). Many youth do not have a choice regarding attendance to religious services; church, synagogue or mosque attendance is often part of a family practice. In such cases, participation in religious services does not reflect an adolescent’s spirituality or even a desire to participate in religious activities (Marsiglia et al. 2005), and the simple act of attending religious services, which can increase social networks and social ties (Smith 2003, Strawbridge et al. 1997; Wills et al. 2004), may not be enough to act as a protective factor against substance use. Attending religious services may only be protective to the degree that the adolescent has internalized religious beliefs, attitudes, and directives (Longest and Vaisey 2008).

In order to see the full effect of religiosity on substance use, both internal and external religiosity needs to be examined concurrently because religiosity can have different profiles for influencing substance use. These differential profiles create four distinct groups of adolescents: (1) those with high internalized and high externalized religiosity; (2) those with low internalized and low externalized religiosity; (3) those with high internalized and low externalized religiosity; and (4) those with low internalized and high externalized religiosity. Religiosity is most protective for adolescents who have both high internal and high external religiosity because the influence of subjective beliefs is strengthened by a community of believers linked to a set of shared religious practices (Longest and Vaisey 2008). For the remaining three groups of adolescents, the impact of religiosity varies because these adolescents do not have the full benefit of both social capital and internal religious meaning. For example, adolescents who have high external religiosity and high internal religiosity, religiosity acts as a protective factor against marijuana use. On the other hand, for adolescents who have high external religiosity and low internal religiosity, religiosity acts as a risk factor for using marijuana (Longest and Vaisey 2008). Thus, if a young person does not internalize religious teachings, the mere participation on religious services and other religion sponsored networks can increase the opportunities for prosocial outcomes but also the opportunities to be exposed and use alcohol and other drugs.

Although, studies examining the relationship between substance use and religiosity of adolescents living in Mexico are limited, research does indicate that religiosity may have these different profiles for influencing substance use of Mexican youth living in Mexico, rather than just simply having an overall protective effect (Benjet et al. 2007a, b). For example, religious youth living in Mexico City are less likely to have drug use opportunities and to have lower lifetime substance use (Benjet et al. 2007b), however highly religious youth are no different in 12-month substance use patterns or in plans to use drugs if given the opportunity to youth with no religious affiliation (Benjet et al. 2007a). These findings highlight the complexity of religiosity in Mexico and the need to further refine the understanding of the relationship between religiosity and substance use.

In summary, this article explores how external religiosity and internal religiosity interact to create differential pathways for adolescents and how these pathways exert both risk and protective influences on Mexican youth from a social capital perspective. This perspective allows us to view religiosity as a resource from which adolescents may draw from in order to refrain from substance use. Furthermore, by accounting for other social capital impacting adolescent substance use (e.g. parental monitoring and a network of non-deviant peers), this study elucidates the impact of religiosity on adolescent substance use. As previous research has suggested external religiosity (church attendance) is not sufficiently protective against substance use among youth. Therefore we hypothesize that (1) internal religiosity will be protective against both cigarette and alcohol use above and beyond other forms of social control (i.e. family, peers). Additionally, in light of current findings suggesting a complex interaction relationship between internal and external religiosity among youth in the US, we also hypothesize that (2) the relationship between external religiosity and substance use is conditional on the level of internal religiosity of youth in central Mexico.

Methods

The cross-sectional data for this project were collected from students enrolled in an alternative schooling system in the state of Guanajuato, Mexico. The Videobachillerato (VIBA) (video high school) program was designed to reach students who could not afford or did not live near a traditional high school. The majority of students attending these alternative schools come from families with limited resources who live in rural or semi-rural areas of Guanajuato. Eight of the 252 VIBA centers were randomly selected, and 702 students enrolled in those eight VIBA centers during the 2006–2007 school year completed questionnaires. The students were asked about sexual and reproductive health, knowledge about HIV/AIDS, physical and mental health status, and substance use. Under the direction of the Arizona State University (ASU) research team and with IRB approval, school psychologists in each VIBA explained the voluntary, anonymous and confidential nature of the project to every student, received verbal consent from each student regarding participation, and administered the questionnaire to the consented students. The questionnaire was created in Spanish by a native Spanish speaking affiliate of the Southwest Interdisciplinary Research Center. Before administering the questionnaire to the participants, it was also edited by native Spanish speaking reviewers. Following data collection, the questionnaire was then translated into English following standard procedures set forth by the Arizona State University IRB. Data for the project were received by the research team at ASU as a de-identified database for secondary analyses, and from these data a 65 page report was prepared and presented to the Sistema Avanzado de Bachillerato y Educacion Superior (SABES) and VIBA with information detailing the mental and physical health of the students, as well as conclusions and recommendations regarding improvements to the overall health of students in the VIBA program.

The survey had an overall response rate of 95%. Approximently 60% of the students who completed the questionnairewere girls. The low number of boys may be due to the traditionally higher dropout rate of boys, or, in light of the historically high migration rates in Guanajuato, one of the highest in Mexico, it could be that many boys had already migrated to the US (Massey et al. 2002).While their ages ranged from 14 to 24 years, 90% of the sample were between 14 and 18 years old, the traditional age range for secondary education.

The analytic sample size for this study only includes participants ages 14–17, due to the differing legal expectations and substance use norms for participants aged 18 years and older. In addition, because of the small variance in religious affiliation (95% Catholic; 0.4% Evangelical; 0.3% Jehovah Witness; 0.3% Adventist; 0.1% Mormon; 0.4% other; and 2.8% no religious affiliation) and the need to control for variations in religious traditions across religions, the analytic sample was restricted to only youth who identified themselves as Roman Catholic. The final analytic sample consists of 506 Catholic youth ages 14–17 (boys = 35%).

Variables

To assess substance use in the past 30 days, two dependent variables (alcohol use and cigarette use) were used. Alcohol use was assessed by frequency of alcohol use: “In the last 30 days, how many times did you drink an alcoholic beverage?” and cigarette use was measured by frequency of cigarette use: “In the last 30 days, how many times did you smoke tobacco or cigarettes?” These frequency of use questions ranged from (0) none to (8) more than 100 times; however, because neither alcohol nor cigarette use were normally distributed (i.e. both were positively skewed), both variables were dichotomized into (0) no use during the past 30 days and (1) any use in the past 30 days. Frequency of use and the dichotomous versions of each of the substance use measures were drawn from studies of adolescents in Monterrey, Mexico (Kulis et al. 2008a, b).

Following Longest and Vaisey (2008), religiosity was measured continuously with two indicators: internal religiosity and external religiosity. Internal religiosity, was assessed by the question, “How important is your religion to you?” and ranged from (0) Not important to (3) Very important. External religiosity was measured by asking, “How often do you attend religious services at your church?” and ranged from (0) Never to (4) Each week. These questions have been used to assess religiosity among adolescents living in Mexico as part of the Mexican Adolescent Mental Health Survey (Benjet et al. 2007a, b). To assess the conditional effect of internal religiosity on external religiosity, an interaction term was produced by multiplying internal religiosity and external religiosity to create the religiosity interaction, which ranged from (0) low internal, low external to (12) high internal, high external. In order to properly account for multicollinearity, internal religiosity, external religiosity, and the religiosity interaction were centered.

Because risk factors for drug and alcohol use among Mexican adolescents also include overall social tolerance to substance use (Villatoro et al. 1998), parental monitoring (Fèlix-Ortiz et al. 2001), peer pressure and peer influence (Latimer et al. 2004; Villatoro et al. 1998), age (Villatoro et al. 1998), gender (Villatoro et al. 1998), school failure and dropping out of school (Villatoro et al. 1999; Latimer et al. 2004), birth place (Villatoro et al. 1998), and residential instability (Kulis et al. 2007), controls were included in the models. Parental monitoring consists of five questions, which have been used to examine parental monitoring among adolescents living in Mexico (Benjet et al. 2007a, b): How often does your dad or mom: (a) know what you do with your free time; (b) know who you hang out with; (c) ask you where you are going when you leave the house; (d) generally know what you do after school; and (e) tell you what time you need to return home. Using a 4-point Likert scale, all questions ranged from (1) never to (4) always. The mean of the items scores were calculated to create the parental monitoring scale (α = .686). Peers’ reaction to substance use was assessed by the question, “How would your best friends react if they found out that you got drunk (smoked cigarettes)?” Peers’ reaction was categorized into dummy variables: (1) positive peer reaction and (2) negative peer reaction with ‘no reaction’ as the reference group. These questions have been used with Mexican heritage students living in the southwestern US (Kulis et al. 2005).

Other control variables include grades, living arrangements, place of birth, gender, and age. Participants reported their average high school grade point average using a 6–10 point grading system as is common in Mexico. Four options were given: 9.0–10 (equivalent to an A average in the US), 8.0–8.9 (B equivalent), 7.0–7.9 (C equivalent), and 6.0–6.9 (D average). Living arrangements measured if the participant was (0) living in a two-parent household (biological or step) or (1) not living in a two-parent household. Place of birth measured if the participant was (0) not born in the county where they currently live or (1) born in the county where they currently live. Finally, boys were the reference group for gender and age was continuous, ranging from 14 to 17 years old.

Analysis Strategy

In order to examine the impact of internal and external religiosity on alcohol and cigarette use, while controlling for other forms of social capital, stepwise logistic regression using Stata 10 was employed beginning with the control variables, followed by internal religiosity and external religiosity, with the final models including the religiosity interaction. Stata 10 was used in order to allow for the characteristics of complex designs, such as cluster, and strata variables, so that estimates and standard errors are unbiased (StataCorp 2009).

Results

All descriptive statistics are provided in Table 1. Forty-four percent of students reported alcohol use in the past 30 days, and 22% reported having smoked cigarettes during that same time period. The sample reported relatively high levels of internal religiosity (μ = 2.49, SD = 0.69), indicating their religion was between important and very important to them. Despite high internal religiosity, the majority of the sample reported attending church just a few times a year, thus having lower levels of external religiosity (μ = 2.44, SD = 1.29). Students reported their parents sometimes monitored their behavior (μ = 2.39, SD = 0.61) and that the majority of their friends would have a negative reaction if they drank alcohol (54%) or smoked cigarettes (55%). The average student was 16 years old, a girl (65%), had a C- grade point average (μ = 1.64, SD = 0.71), and lived in a two-parent household (84%).

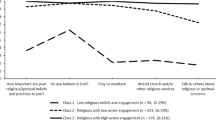

The results for the logistic regression models predicting 30-day alcohol use are shown in Table 2. The first column of Table 2, Model 1, presents the likelihood of alcohol use on the control variables. As parental monitoring increases, the odds of using alcohol decrease by 62% (OR = 0.38, p < .001, 95%CI = 0.25, 0.60). Expecting a negative peer reaction to drinking alcohol (OR = 0.56, p < .05, 95%CI = 0.34, 0.91), having higher grades (OR = 0.65, p < .01, 95%CI = 0.47, 0.90), and being born in the same municipality as attending school (OR = 0.49, p < .01, 95%CI = 0.31, 0.77) also significantly reduce the likelihood of alcohol use. On the other hand, living in a single parent household (OR = 2.18, p < .05, 95%CI = 1.15, 4.12) significantly increases the odds of alcohol use. Expecting a positive peer reaction to alcohol, age, and gender were not significant predictors in the likelihood of using alcohol in the past 30 days. Model 2 adds internal religiosity and external religiosity to the logistic regression. As internal religiosity increases, the odds of drinking alcohol in the past 30 days decrease by 25% (OR = 0.75, p < .10, 95%CI = 0.54, 1.03); however, external religiosity is not a significant predictor of the likelihood of alcohol use. All significant control variables from Model 1 remained significant and in the expected direction, and age became moderately significant (OR = 1.32, p < .10, 95%CI = 1.00, 1.75. In Model 3, the religiosity interaction is introduced to the model. The interaction between internal religiosity and external religiosity has a significant negative relationship with alcohol use (OR = 0.79, p < .05, 95%CI = 0.63, 1.00). As Fig. 1 shows, adolescents who have low internal religiosity and high external religiosity have the highest odds of using alcohol in the past 30 days, while adolescents with high internal religiosity and high external religiosity have the lowest odds of using alcohol in the past 30 days. When the interaction is included, internal religiosity remains significant and reduces the likelihood of using alcohol (OR = 0.69, p < .05, 95%CI = 0.49, 0.96) while external religiosity remains non-significant. All significant control variables from Model 2 remain significant and in the expected direction.

Table 3 presents the results for the logistic regression models predicting 30-day cigarette use. In Model 1, the odds of cigarette use on the control variables are shown. Like alcohol use, as parental monitoring increases, the odds of smoking cigarettes decrease by 42% (OR = 0.58, p < .01, 95%CI = 0.38, 0.87), and expecting a negative peer reaction decreases cigarette smoking by 53% (OR = 0.47, p < .01, 95%CI = 0.26, 0.82). Expecting a positive peer reaction, age, gender, grades, living arrangement, and location of birth were not significant predictors in the odds of smoking cigarettes. Unlike alcohol, when internal religiosity and external religiosity are added to the logistic regression, as shown in Model 2, neither religiosity variable is a significant predictor in the odds of cigarette smoking. All significant control variables from Model 1 remain significant and in the expected direction. In Model 3, when the religiosity interaction is introduced to the model, the interaction between internal religiosity and external religiosity has a significant negative relationship with cigarette smoking (OR = .71, p < .05, 95%CI = 0.52, 0.98). As Fig. 2 shows, adolescents who have low internal religiosity and high external religiosity have the highest odds of smoking cigarettes in the past 30 days, while adolescents with both low internal religiosity and low external religiosity have the lowest odds of smoking cigarettes in the past 30 days. When the interaction is included, both internal religiosity and external religiosity remain nonsignificant. All significant control variables from Model 1 remain significant and in the expected direction.

Discussion

In response to the increasing rates of substance use among adolescents in Mexico (Arillo-Santillán et al. 2005; Benjet et al. 2007; Bird et al. 2006; Lotrean et al. 2005; Medina-Mora et al. 2003; Ritterman et al. 2009; Villalobos and Rojas 2007), and findings that suggest religiosity as protective against substance use (Amey et al. 1996; Chatters 2000; Cochran and Akers 1989; Miller et al. 2000; Nonnemaker et al. 2003; Wallace and Forman 1998), this study examined the relationship between religiosity and substance use among Mexican youth. For Catholic youth living in communities of strong Roman Catholic heritage, two hypotheses were tested: First, since studies have reported inconsistent findings on the protective nature of external religiosity for substance use (Hodge et al. 2001; Marsiglia et al. 2005), we hypothesized that only internal religiosity would serve as a protective factor above and beyond other traditional social controls (i.e. family and peers); and secondly, guided by US research showing an increasingly complex relationship among internal and external religiosity (Longest and Vaisey 2008), we hypothesized that the relationship between internal religiosity and substance use would be moderated by external religiosity.

The first hypothesis was partially supported. The importance an adolescent places on their religion (internal religiosity) serves as a significant protective factor for alcohol use, but not for cigarette use. This finding helps extend our understanding of the protective nature of religiosity on alcohol use on US youth (Amey et al. 1996; Cochran and Akers 1989; Miller et al. 2000; Wallace and Forman 1998; Marsiglia et al. 2005) to include Mexican youth as well. For adolescents living in central Mexico, this study found that having internal religiosity acts as a protective factor against alcohol use, and can provide social capital potentially giving these adolescents norms and sanctions encouraging prosocial behaviors (Longest and Vaisey 2008). Youth who place a high importance on religion could surround themselves with like-minded adolescents who could not only provide positive social support (Strawbridge et al. 1997) but also shield the adolescent against drug use opportunities (Amoateng and Bahr 1986; Bahr et al. 1998; Longest and Vaisey 2008; Mason and Windle 2001; Oetting et al. 1998). Although cigarette use was not significant, this finding may be more reflective of the societal, cultural, and religious norms in Mexico surrounding substance use, rather than reflective of the actual association between cigarettes and religiosity. In Mexico, with its strong Catholic traditions, alcohol has historically been used for religious purposes and the norms about who drinks alcohol (Medina-Mora 2007) are more prescribed than norms surrounding cigarette smoking.

The second hypothesis was fully supported for both alcohol and cigarette use; the relationship between external religiosity and substance use (alcohol and cigarettes) was moderated by internal religiosity. The interaction between internal and external religiosity had differing effects depending on the substance examined. These findings indicate that for adolescents, four different religiosity pathways emerge to influence substance use, supporting previous US-based (Longest and Vaisey 2008): high internal and high external, low internal and low external, high internal and low external and high external and low internal. However, unlike previous research (Longest and Vaisey 2008), the protective effect of adolescents in the high internal and high external group is only consistent for alcohol use. These findings indicate that adolescents who place a higher importance on religion and attend church more frequently are more protected against using alcohol; yet this pattern is not as protective for cigarette use. In fact, as our findings indicate, adolescents who place less importance on religion and attend church less frequently were more protected against using cigarettes.

These findings indicate that having congruency between internal and external religiosity may be protective against substance use, while incongruence between adolescent’s personal religious beliefs (internal religiosity) and outward actions (e.g. external religiosity/church attendance) could place adolescents at risk for substance use. For both alcohol and cigarette use, adolescents who have lower internal religiosity and higher external religiosity have the highest substance use. Simply put, adolescents have the highest odds of using alcohol and cigarettes when they place lower importance on religion but attend religious services weekly. Because adolescents often do not have a choice whether to attend religious services, a decision often made by parents (Marsiglia et al. 2005), simply requiring attendance of religious services may not be enough to protect youth against using substances because attendance does not reflect an adolescent’s spirituality or even a desire to participate in religious activities (Marsiglia et al. 2005). This may be particularly true in Mexico where Roman Catholic traditions are an integral part of Mexican culture (Mosqueda 1986). In fact, these findings suggest that requiring religious attendance when the adolescent does not place personal importance on religion could be detrimental to protecting against alcohol and cigarette use, and indicate that, as with US adolescents (Longest and Vaisey 2008), attending religious services is only protective to the extent that the adolescent has internalized religious attitudes and beliefs (Longest and Vaisey 2008).

Although these findings highlight the complexity of studying religiosity and advance our understanding of the interaction between internal and external religiosity, there are several limitations to this study. First, the cross sectional nature of the study design limited the understanding of intricacies in the relationship between religiosity and substance use. Although the measures of substance use assessed the last 30 days, the measures of religiosity were current and it is therefore possible that some adolescents’ religiosity changed after using substances. Future research should utilize longitudinal data in order to allow for time ordering to make the relationship between religiosity and substance use causal rather than associational. Second, as the questionnaire was given in a school setting, those not attending school or absent on the day of the questionnaire were not given the opportunity to participate. It should be noted that adolescents who did not participate in the survey due to dropping out of school may have higher rates of substance use than those who stayed in school and participated in this study (Townsend et al. 2007). While their impact on the present study in unknown, it is likely that their participation in this project would have increased the overall percentage of students using alcohol and cigarettes. Future research should focus on capturing a larger body of the adolescent population. Fourth, the religiosity variables used in this study were both single-item measures, and our final sample was composed of only those who self-reported their religious affiliation as Catholic. Multi-item religiosity scales should be used in future research to better elucidate the interaction between internal and external religiosity. Furthermore, although studying adolescents of other religious backgrounds would add to the understanding of religiosity and substance use, 92% of our sample reported their religious affiliation as Catholic, with only 2% reporting an affiliation with a different religious group, 3% reporting no religious affiliation and 3% not responding to the question. This limited the analyses and generalizability to other religious faiths. Lastly, this study did not have any controls accounting for the possibility that the adolescents’ religious affiliation and religious participation may have been determined by their parents. A control variable accounting for parental religious influence should be included in future studies in order to gain additional insight into the religiosity interaction. Despite these limitations, these findings add an interesting contribution to our understanding of religiosity as a form of social capital for Mexican youth in Mexico, as well as for immigrant Mexican youth residing in the US.

Conclusion

This study not only contributes to our understanding of the impact of religiosity on substance use in Mexico, but highlights the importance of understanding religiosity as a multidimensional phenomenon which can lead to differential substance use patterns. Furthermore, understanding religiosity as a form of social capital highlights the potential influence religion can have in the lives of Mexican youth.

These findings also contribute to further development of social capital theory as an approach to the study of religiosity and drug use among young people. Due to the homogeneity in religious affiliation in many regions of Mexico and relatively high church attendance, participating in religious services cannot be automatically equated to the American understanding of such behavior as a form of social capital (Bartkowski and Xu 2007). This study indicates that social capital in Mexico requires an individual act (internalized religion), not just a normative social act (church attendance), in order for a behavior to be protective against drug use. In small Mexican towns church attendance is normative, in some cases is compulsory like attending school, and it is often one of the few social activities available to youth (Camp 2000). Attending religious services in that context is not necessarily by itself protective, it appears as though it is the existence of a subjective form of social capital (such as internal religious beliefs) that makes church attendance a more traditional form of social capital to be protective against alcohol and other drugs. In social and cultural contexts such as Mexico and among low acculturated Mexican immigrant communities in the USA, the mere attendance of faith based activities should probably not be automatically interpreted as protective. This study helps demonstrate the potential importance of assessing for both the adolescents’ subjective religious beliefs, in addition to their church attendance, before arriving to any conclusions about religiosity as a form of social capital.

While having pro-social peers and parents that closely monitor their adolescent’s behavior is effective at reducing substance use, religiosity appears to contribute to protecting adolescents against substance use. However, the protective nature of religiosity is not one-dimensional. Having incongruence between internal religious beliefs and external church attendance appears to place Mexican youth at greatest risk of alcohol and cigarette use. By understanding how religiosity in Mexico influences an adolescent’s decision to use substances, parents and other community members who interact with youth can start to think about how subtance use prevention programs targeting Mexican youth might benefit from these new findings.

References

Amey, C. H., Albrecht, S. L., & Miller, M. K. (1996). Racial differences in adolescent drug use: The impact of religion. Substance Use and Misuse, 31(10), 1311–1332.

Amoateng, A. Y., & Bahr, S. J. (1986). Religion, family, and adolescent drug use. Sociological Perspectives, 29(1), 53–76.

Arillo-Santillán, E., Lazcano-Ponce, E., Hernandez-Avila, M., Fernández, E., Allen, B., Valdes, R., et al. (2005). Association between individual and contextual factors and smoking in 13, 293 Mexican students. American Journal of Preventative Medicine, 28(1), 41–51.

Bahr, S. J., Maughan, S. L., Marcos, A. C., & Li, B. (1998). Family, religiosity, and the risk of adolescent drug use. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 60(4), 979–992.

Baron, S., Field, J., & Schuller, T. (2000). Social capital: Critical perspectives. New York: Oxford University Press.

Bartkowski, J. P., & Xu, X. (2007). Religiosity and teen drug use reconsidered: A social capital perspective. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 32, 182–194.

Benjamins, M., & Buck, A. C. (2009). Religion: A sociocultural predictor of health behaviors in Mexico. Journal of Aging and Health, 20(3), 290–305.

Benjet, C., Borges, G., Medina-Mora, M. E., Blanco, J., Zambrano, J., Orozco, R., et al. (2007a). Drug use opportunities and the transition to drug use among adolescents from the Mexico City Metropolitan Area. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 90(2–3), 128–134.

Benjet, C., Borges, G., Medina-Mora, M. E., Fleiz, C., Blanco, J., Zambrano, J., et al. (2007b). Prevalence and socio-demographic correlates of drug use among adolescents: Results from the Mexican adolescent mental health survey. Addiction, 102(8), 1261–1268.

Bird, Y., Moraros, J., Olsen, L., Coronado, G., & Thompson, B. (2006). Adolescents′ smoking behaviors, beliefs on the risk of smoking, and exposure to ETS in Juarez, Mexico. American Journal of Health Behavior, 30, 435–446.

Borges, G., Medina-Mora, M. E., Orozco, R., Fleiz, C., Villatoro, J., Rojas, E., et al. (2009). Unmet needs for treatment of alcohol and drug use in four cities in Mexico. Salud Mental, 32, 327–333.

Camp, R. A. (2000). The cross in the polling booth: Religion, politics, and the laity in Mexico. Latin America Research Review, 29(3), 69–99.

Chatters, L. M. (2000). Religion and health: Public health research and practice. Annual Review of Public Health, 21(1), 335–367.

Cochran, J. K., & Akers, R. L. (1989). Beyond hellfire: An exploration of the variable effects of religiosity on adolescent marijuana and alcohol use. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 26(3), 198–225.

Fèlix-Ortiz, M., Villatoro Velàzquez, J. A., Medina-Mora, M. E., & Newcomb, M. D. (2001). Adolescent drug use in Mexico and among Mexican American adolescents in the United States: Environmental influences and individual characteristics. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 7(1), 27–46.

Fiala, W. E., Bjorck, J. P., & Gorsuch, R. (2002). The religious support scale: Construction, validation, and cross-validation. American Journal of Community Psychology, 30, 761–786.

Hadaway, C. K., Elifson, K. W., & Petersen, D. M. (1984). Religious involvement and drug use among urban adolescents. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 23(2), 109–128.

Hawkins, J. D., Graham, J. W., Maguin, E., Abbott, R., Hill, K. G., & Catalano, R. F. (1997). Exploring the effects of age of alcohol use initiation and psychosocial risk factors on subsequent alcohol misuse. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 58, 280–290.

Hodge, D. R., Cardenas, P., & Montoya, H. (2001). Substance use: Spirituality and religious participation as protective factors among rural youths. Social Work Research, 25, 153–161.

Kulis, S., Marsiglia, F. F., Castillo, J., Bercerra, D., & Nieri, T. (2008a). Drug resistance strategies and substance use among adolescents in Monterrey, Mexico. Journal of Primary Prevention, 29, 167–192.

Kulis, S., Marsiglia, F. F., Elek, E., Dustman, P., Wagstaff, D. A., & Hecht, M. (2005). Mexican/Mexican American adolescents and keepin’ it REAL: An evidence-based substance use prevention program. Children and Schools, 27, 133–145.

Kulis, S., Marsiglia, F. F., Lingard, E. C., Nieri, T., & Nagoshi, J. (2008b). Gender identity and substance use among students in two high schools in Monterrey, Mexico. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 95, 258–268.

Kulis, S., Marsiglia, F. F., Sicotte, D. M., & Nieri, T. (2007). Neighborhood effects on youth substance use in a southwestern city. Sociological Perspectives, 50, 273–301.

Kuri-Morales, P., Cravioto, P., Hoy, M. J., & Tapia-Conyer, R. (2000). Assessment of cigarette sales to minors in Mexico. Tobacco Control, 9, 435–437.

Latimer, W., Floyd, L. J., Kariis, T., Novotna, G., Exnerova, P., & O’Brien, M. (2004). Peer and sibling substance use: Predictors of substance use among adolescents in Mexico. Revista Panamericana de Salud Publica, 15(4), 225–232.

Levin, J. S., Markides, K. S., & Ray, L. A. (1996). Religious attendance and psychological well-being in Mexican Americans: A panel analysis of three-generation data. The Gerontologist, 36, 454–463.

Li, X., Stanton, B., & Feigelman, S. (2000). Impact of perceived parental monitoring on adolescent risk behavior over 4 years. Journal of Adolescent Health, 27(1), 49–56.

Longest, K. C., & Vaisey, S. (2008). Control or conviction: Religion and adolescent initiation of marijuana use. Journal of Drug Issues, 38(3), 689–715.

Lotrean, L. M., Sanchez-Zamorano, L. M., Valdes-Salgado, R., Arillo-Santillán, E., Allen, B., Hernández-Avila, M., et al. (2005). Consumption of higher numbers of cigarettes in Mexican youth: The importance of social permissiveness of smoking. Addictive Behaviors, 30(5), 1035–1041.

Marsiglia, F. F., Kulis, S., Martinez-Rodriguez, G., Becerra, D., & Castillo, J. (2009). Culturally specific youth substance abuse resistance skills: Applicability across the U.S.-Mexico border. Research on Social Work Practice, 19(2), 152–164.

Marsiglia, F. F., Parsai, M., Kulis, S., & Nieri, T. (2005). God forbid! Substance use among religious and nonreligious youth. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 75(4), 585–598.

Mason, W. A., & Windle, M. (2001). Family, religious, school and peer influences on adolescent alcohol use: A longitudinal study. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 62(1), 44–53.

Massey, D. S., Durand, J., & Malone, N. J. (2002). Beyond smoke and mirrors. Mexican immigration in an era of economic integration. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Medina-Mora, M. (2007). Mexicans and alcohol: Patterns, problems and policies. Addiction, 102(7), 1041–1045.

Medina-Mora, M. E., Borges, G., Fleiz, C., Rojas, E., et al. (2006). Prevalence and correlates of drug use disorders in Mexico. Revista Panamericana de Salud Publica, 19, 265–276.

Medina-Mora, M. E., Cravioto, P., Villatoro, J., Fleiz, C., Galvan-Castillo, F., & Tapia-Conyer, R. (2003). Drug used among adolescents: Results from the National Survey on Addictions, 1998. Salud Publica de Mexico, 45, S16–S25.

Miller, L., Davies, M., & Greenwald, S. (2000). Religiosity and substance use and abuse among adolescents in the National Comorbidity Survey. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 39(9), 1190–1197.

Mosqueda, L. J. (1986). Chicanos, catholicism and political ideology. Lanham, MD: University Press of America.

Nasim, A., Utsey, S. O., Corona, R., & Belgrave, F. Z. (2006). Religiosity, refusal efficacy, and substance use among African-American adolescents and young adults. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse, 5(3), 29–49.

Nonnemaker, J. M., McNeely, C. A., & Blum, R. W. (2003). Public and private domains of religiosity and adolescent health risk behaviors: Evidence from the national longitudinal study of adolescent health. Social Science and Medicine, 57(11), 2049–2054.

Oetting, E. R., Donnermeyer, J. F., & Deffenbacher, J. L. (1998). Primary socialization theory: The influence of the community on drug use and deviance. Substance Use and Misuse, 33(8), 1629–1665.

Ostaszewski, K., & Zimmerman, M. A. (2006). The effects of cumulative risks and promotive factors on urban adolescent alcohol and other drug use: A longitudinal study of resiliency. American Journal of Community Psychology, 38(3/4), 237–249.

Piko, B. F., & Fitzpatrick, K. M. (2004). Substance use, religiosity, and other protective factors among Hungarian adolescents. Addictive Behaviors, 29(6), 1095–1107.

Putman, R. D. (2000). Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Resnick, M. D., Ireland, M., & Borowsky, I. (2004). Youth violence perpetration: What protects? What predicts? Findings from the national longitudinal study of adolescent health. Journal of Adolescent Health, 35(5), 424.e1–424.e1.

Ritterman, M. L., Fernald, L. C., Ozer, E. J., Adler, N. E., Gutierrez, J. P., & Syme, S. L. (2009). Objective and subjective social class gradients for substance use among Mexican adolescents. Social Science and Medicine, 68, 1843–1851.

Scott, L. D., Munson, M. R., McMillen, J. C., & Ollie, M. T. (2006). Religious involvement and its association to risk behaviors among older youth in foster care. American Journal of Community Psychology, 38, 223–236. doi:10.1007/s10464-006-9077-9.

Smith, C. (2003). Religious participation and network closure among American adolescents. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 42(2), 259–267.

Stark, R. (1996). Religion as context: Hellfire and delinquency one more time. Sociology of Religion, 57, 163–173.

Stark, R., & Bainbridge, W. S. (1996). Religion, Deviance, and Social Control. New York: Routledge.

StataCorp. (2009). Stata Statistical Software: Release 10. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP.

Steinman, K. J., & Zimmerman, M. A. (2004). Religious activity and risk behavior among African American adolescents: Concurrent and developmental effects. American Journal of Community Psychology, 33(3/4), 151–161.

Strawbridge, W. J., Cohen, R. D., Shema, S. J., & Kaplan, G. A. (1997). Frequent attendance at religious services and mortality over 28 years. American Journal of Public Health, 87(6), 957–961.

Townsend, L., Flisher, A. J., & King, G. (2007). A systematic review of the relationships between high school dropout and substance use. Clinical Child and family Psychology, 10(4), 295–317.

Turner, S. (1994). Family variables related to adolescent substance misuse: Risk and resiliency factors. In T. P. Gullotta, G. R. Adams, & R. Montemayor (Eds.), Substance misuse in adolescence (pp. 36–55). Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

University of Michigan News and Information Services. (1997). Study of worldwide rates of religiosity, church attendance. Retrieved 3/5, 2010, from http://www.ns.umich.edu/index.html?/Releases/1997/Dec97/chr121097a.

Van Den Bree, M. B. M., Whitmer, M. D., & Pickworth, W. B. (2004). Predictors of smoking development in a population-based sample of adolescents: A prospective study. Journal of Adolescent Health, 35(3), 172–181.

Van der Gaag, M., & Snijders, T. (2004). Proposals for the measurement of individual social capital. In H. Flap & B. Völker (Eds.), Creation and return of social capital (pp. 199–228). London: Routledge.

Villalobos, A., & Rojas, R. (2007). Consumo de tabaco en México. Resultados de las Encuestas Nacionales de Salud 2000 y 2006. [Tobacco consumption in Mexico. Results of the National Health Studies 2000 and 2006.] Salúd Publica de México, 49(Supplement 2), S147–S154.

Villatoro, J., Hernandez, I., Hernandez, H., Fleiz, C., Blanco, S., & Medina-Mora, M. E. (2004). Encuestas de consumo de drogas de estudiantes III [Survey of student drug use III]. 1991–2003 SEP-INPRFM. Mexico City: Mexican National Institute of Psychiatry-Secretary of Education.

Villatoro, J., Medina-Mora, M. E., Cardiel, H., Fleiz, C., Alcántara, E., Hernández, S., et al. (1999). La situación del consumo de sustancias entre estudiantes de la Ciudad de México: medición otoño 1997 [The substance consumption circumstances among students in Mexico City; Fall 1997 measurement]. Salud Mental, 22, 18–30.

Villatoro, J. A., Medina-Mora, M. E., Juárez, F., Rojas, E., Carreño, S., & Berenzon, S. (1998). Drug use pathways among high school students of Mexico. Addiction, 93(10), 1577–1588.

Wallace, J. M. (1999). The social ecology of addiction: Race, risk, and resilience. Pediatrics, 103(5), 1122–1127.

Wallace, J. M., Brown, T. N., Bachman, J. G., & Laveist, T. A. (2003). The influence of race and religion on abstinence from alcohol, cigarettes and marijuana among adolescents. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 64, 843–848.

Wallace, J. M., Jr., & Forman, T. A. (1998). Religion’s role in promoting health and reducing risk among American youth. Health Education and Behavior, 25(6), 721–741.

Wallace, J. M., Jr., Yamaguchi, R., Bachman, J. G., O’Malley, P. M., Schulenberg, J. E., & Johnson, L. D. (2007). Religiosity and adolescent substance use: The role of individual and contextual influences. Social Problems, 54(2), 308–327.

Wills, T. A., Cleary, S. D., Filer, M., Shinar, O., Mariani, J., & Spera, K. (2001). Temperament related to early-onset substance use: Test of a developmental model. Prevention Science, 2, 145–163.

Wills, T. A., Gibbons, F. X., Gerrard, M., Murry, V. M., & Brody, G. H. (2003). Family communication and religiosity related to substance use and sexual behavior in early adolescence: A test for pathways through self-control and prototype perceptions. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 17(4), 312–323.

Wills, T. A., Yaeger, A. M., & Sandy, J. M. (2004). Buffering effect of religiosity for adolescent substance use. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 17(1), 24–31.

Wilson, C. E. (2008). The politics of Latino faith: Religion, identity, and urban community. New York: New York University Press.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study was provided by the Arizona State University (ASU) Foundation Professorship of Cultural and Diversity and Health. Manuscript development was supported by grant number P20MD002316 from the National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Arizona State University, the NIMHD, and the NIH had no further role in the study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of ASU, the NIMHD or the NIH.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Marsiglia, F.F., Ayers, S.L. & Hoffman, S. Religiosity and Adolescent Substance Use in Central Mexico: Exploring the Influence of Internal and External Religiosity on Cigarette and Alcohol Use. Am J Community Psychol 49, 87–97 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-011-9439-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-011-9439-9