Abstract

Incarceration fractures relationship ties and has been associated with unprotected sex. Relationships where both individuals have a history of incarceration (dual incarceration) may face even greater disruption and involve more unprotected sex than relationships where only one individual has been incarcerated. We sought to determine whether dual incarceration is associated with condom use, and whether this association varies by relationship type. Data come from 499 sexual partnerships reported by 210 individuals with a history of incarceration. We used generalized estimating equations to examine whether dual incarceration was associated with condom use after controlling for individual and relationship characteristics. Interaction terms between dual incarceration and relationship commitment were also examined. Among currently committed relationships, dual incarceration was associated with inconsistent condom use (AOR: 4.33; 95% CI 1.02, 18.45). Dual incarceration did not affect condom use in never committed relationships. Reducing incarcerations may positively impact committed relationships and subsequently decrease HIV-related risk.

Resumen

El encarcelamiento fractura los lazos relacionales y ha sido asociado con relaciones sexuales sin protección. Es posible que las relaciones en las que ambos individuos tienen una historia de encarcelamiento (encarcelamiento dual) enfrenten aún mayor disrupción e involucren más sexo sin protección que las relaciones en las que sólo un individuo ha sido encarcelado. Nuestro objetivo fue determinar si el encarcelamiento dual está asociado con el uso de condón, y si esta asociación varía según el tipo de relación. Los datos provienen de 499 relaciones sexuales reportadas por 210 individuos con historia de encarcelamiento. Usamos ecuaciones de estimación generalizadas para examinar si el encarcelamiento dual estaba asociado con el uso de condón luego de controlar por características individuales y de la relación. También analizamos los términos de interacción entre el encarcelamiento dual y el compromiso en la relación. En relaciones comprometidas en el presente, el encarcelamiento dual estaba asociado con uso inconsistente del condón (AOR: 4.33; IC 95%: 1.02, 18.45). En relaciones nunca comprometidas, el encarcelamiento dual no afectó el uso de condón. Reducir el encarcelamiento puede tener un impacto positivo en relaciones comprometidas y, consecuentemente, reducir el riesgo de VIH.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Over 2.2 million individuals in the United States are incarcerated [1]. Further, more individuals are incarcerated in the United States than anywhere else in the world [1]. These high levels of incarceration profoundly impact public health in the United States, and these impacts are experienced both within but especially beyond the walls of the institution [2]. Given that 97% of all prisoners are ultimately released from prison/jail [3], and that more than half of these individuals return to intimate relationships in the community [4], it is critical to understand and document the health impacts of incarceration for both individuals and their sexual partners.

One particular consequence that extends beyond the walls of the institution is increased risk of HIV infection [5–7]. One theoretical rationale for this increased risk is that the constant movement of individuals in and out of jails, or their ‘involuntary mobility,’ contributes to social disorganization in neighborhoods and subsequently impacts both health and crime in these neighborhoods [5, 8, 9]. As applied to HIV risk, this ‘involuntary mobility’ may disrupt individuals’ intimate relationships, which can then affect their sexual behavior [5], and in particular, their condom use. In two separate prospective studies with convenience samples of males at high risk of HIV infection, having been recently incarcerated or having a history of incarceration predicted unprotected sex [6, 7]. Similarly, in a population-based cross sectional study of men who had no history of illicit drug use, those who had recently been incarcerated were significantly more likely to report unprotected sex than those who had not recently been incarcerated [10].

In addition to the impacts of personal incarceration on HIV risk, there is a small but growing body of research which suggests incarceration also affects the HIV risk of individuals’ intimate partners [10–13]. The partner who is ‘left behind’ has to deal with the ramifications of the incarcerated partner’s absence and eventual return, both of which can have exacting economic and social consequences. The disruptions caused by the loss of a partner to incarceration can lead individuals to seek new, potentially risky partners for both economic and social support. In two qualitative studies, Megan Comfort and Hannah Cooper each qualitatively describe how incarceration shapes and constrains women’s relationships with incarcerated male partners, both during and after incarceration [11, 12], and specifically, how such experiences affect sexual behavior within the relationship. For example, partners may engage in unsafe sex following incarceration because they are trying to reconnect after separation and condom-less sex is one way of re-establishing intimacy [9].

Some studies have quantified these effects as well. In a cross sectional study with adolescent females recruited at a reproductive health clinic, having a boyfriend with a history of incarceration was associated with lower condom use [14]. On the contrary, among an adult population of methadone-using men, having a female sexual partner who had a history of incarceration was associated with increased likelihood of condom use and in a separate multivariate model, was also associated with increased likelihood of reporting multiple partners [15]. One interpretation for the finding is that condom use may increase because one or both partners perceive enhanced HIV risk given an observed association between female partner incarceration and multiple partnerships; however, the researchers did not adjust for the effect of multiple partnerships in their models on condom use.

In summary, previous research suggests that incarceration impacts unprotected sex for both incarcerated individuals and their partners. To our knowledge, however, no one has analyzed what happens when both partners have been incarcerated. We expect that the movement of both parties in and out of prison or jail will have an even stronger effect on behaviors within relationships than the incarceration and return of one partner. Accordingly, it may be that consistent condom use will be lower in relationships where there is dual incarceration than in relationships where there is single incarceration because partners will be seeking to re-establish intimacy following their incarcerations and not using condoms allows them to do so.

Further, it may be that dual incarceration will affect condom use behaviors only in relationships in which individuals are committed to each other. That is, the desire to re-establish intimacy may be particularly relevant to individuals in committed relationships where both individuals have experienced incarceration. In contrast, dual incarceration may not be associated with condom use in relationships that have never been committed because factors driving condom use in never committed relationships may not be impacted by dual incarceration.

The current study addresses the gap in understanding of whether dual incarceration matters and for whom it matters using a sample of individuals recently involved in the criminal justice system. Specifically, we examine the effects of dual incarceration on condom use at the partnership level, after controlling for individual level and other relationships level factors that have been theoretically or empirically associated with condom use, including injecting drug use [14], concurrency [15, 16], and relationship violence [17, 18]. We hypothesize that relationships where there is dual incarceration (such that both individuals have ever been incarcerated) will have greater inconsistent condom use than relationships where there is single incarceration. We also examine whether level of commitment in the relationship moderates the effect of dual incarceration on inconsistent condom use, and we expect that being in a committed relationship will amplify the effects of dual incarceration on inconsistent condom use.

Methods

Study Design and Sample

Data for the proposed cross sectional analyses were collected as part of the Structures, Health and Risk among Re-Entrants, Probationers and Partners (SHARRPP) study, a longitudinal study with 302 individuals recruited from New Haven, Connecticut who were [1] aged 18 or older, and [2] had been released from a Connecticut State prison/jail or placed on probation in Connecticut (with no jail time) for a non-violent offense related to drugs in the last year. After individuals were deemed eligible and consented to participate, they completed a self-administered computer assisted structured baseline survey of approximately 90 min in length. Individuals received $40 for participation and the study protocol was approved by the IRB at American University and Yale University.

A total of 302 individuals completed the baseline survey. Participants who reported zero sexual partners in the six months prior to or since their most recent criminal justice (CJ) experience (n = 82), who had never been incarcerated (n = 5), or who had missing data on dual incarceration or HIV risk variables (n = 5) were excluded from the present analysis (final n = 210). To construct the sexual partner grid, individuals were first asked to identify the total number of unpaid sex partners they had in the six months before their most recent criminal justice experience and since their release/beginning of probation (range: 1–46). Next, individuals were asked a series of partnership-specific questions for up to ten unpaid sexual partners. More than half of the sample, or 111 individuals, reported on only one sexual partner; 43 individuals reported on two, 16 individuals reported on three, 8 individuals reported on four, and 33 individuals reported on five or more sexual partners.

Measures

We measured HIV-related risk as follows. Inconsistent condom use: Individuals reported how often they used condoms with each sexual partner they had either vaginal or anal sex with in the 6 months before their most recent CJ experience and since their most recent CJ experience (never/sometimes/usually/always). Individuals who reported always received a ‘0’ for inconsistent condom use in the relationship; all others received a ‘1’.

We measured relationship characteristics as follows. Dual incarceration: Relationships where the participant reported that their sexual partner had been incarcerated at least once received a ‘1’; all others received a ‘0’. Relationship commitment: Never committed relationships were those in which individuals indicated they and their partner had never been married or committed, Past committed relationships were those that had been married or committed in the past but were not currently committed, and current committed relationships were those that were currently married or committed to one another. Relationship duration: Long-term relationships were those in which individuals indicated they and their partner had started their relationship between 5 and 10 years ago, medium-term relationships were those who indicated they had started their relationship between 1 and 5 years ago, and new relationships were those whose relationship had begun in the last year. HIV serodiscordant: A relationship was serodiscordant if the individual reported that at least one individual in the relationship had HIV and the other did not. Paired injection drug use: Individuals reported whether they had ever injected drugs with their sexual partner at any time in the relationship. Individuals who reported yes received a ‘1’; all others received a ‘0’. Paired concurrency: Individuals indicated whether they were having sex with any other people at the same time as they were having sex with each partner in the partner grid in the 6 months before their most recent CJ experience and since their most recent CJ experience (yes/no). Individuals also indicated whether they thought their sex partner was having sex with any other people at the same time as they were having sex with the partner in the partner grid in the 6 months before their most recent CJ experience and since their most recent CJ experience (definitely no, probably no, probably yes, definitely yes). Individuals who reported that they had sex with any other people and that their partner definitely had sex with other people received a ‘1’ for paired concurrency; all others received a ‘0’. Relationship violence: Individuals indicated whether they had ever hit their sexual partner (yes/no) or forced them to have sex (yes/no) and whether their sexual partner ever hit them (yes/no) or forced them to have sex (yes/no). Individuals who reported at least one act of perpetration and victimization received a ‘1’ for relationship violence; all others received a ‘0’.

Individual characteristics were measured as follows. Length of most recent incarceration: we used the dates of entry and release received from the Department of Corrections to calculate the length of the most recent CJ experience for the index participant. If this value was missing for a participant, we used participant’s self-reported dates from the baseline survey. All participants who entered the study via probation received a ‘0’. Participants also reported their age, race, gender, whether they had ever injected drugs and whether they had ever sold sex for money or drugs. Finally, participants reported whether they had personally engaged in concurrency (yes/no) and whether they had perpetrated any violence against their partner (yes/no), and we controlled for these individual-level risk variables because we were interested in looking at paired behaviors across the relationship.

Statistical Analysis

Analyses for the current manuscript proceeded in three phases. First, we conducted bivariate analysis to examine differences in inconsistent condom use by relationship characteristics. Second, we conducted multivariate analysis to examine differences in inconsistent condom use by relationship level characteristics after adjusting for individual characteristics (main effects model). Third, we tested for an interaction between dual incarceration and relationship commitment (interaction model). We created two dummy variables for relationship commitment since it was a three level variable and therefore tested two interactions in the interaction model. For the multivariate analysis, we used generalized estimating equations, which allowed us to take into account correlations within individuals across their sexual partnerships [16]. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS software, version 9.4 [17].

Results

Describing Individuals and Their Relationships

The mean age of participants was 38 years old, the study sample was overwhelmingly male (83%), nearly half of all participants identified as African American and approximately one-third had ever injected drugs. Of the 496 sexual partners reported by participants, 72% were between 18 and 39 years old, 82% were females, almost half were non-Hispanic Blacks and just over 10% reported ever injecting drugs (Table 1).

At the relationship level, nearly half of the relationships were characterized as never committed, though 80% had lasted for more than one year. Both partners had a history of incarceration in nearly a quarter of the relationships. A small proportion of relationships were HIV serodiscordant (5.78%). In only 10% of relationships had partners ever injected drugs together, and bidirectional intimate partner violence was reported in just under 10% of the relationships. Paired concurrency occurred in almost a third of relationships. Finally, though condom use at their first sexual encounter was reported in nearly two-thirds of the relationships, more recent condom use was lower. Specifically, condoms were inconsistently used in three-quarters of the relationships (Table 2).

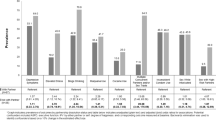

Assessing How Relationship Characteristics Influence Condom Use

In the bivariate analysis, those relationships that were currently committed, of longer duration, and had experienced relationship violence were significantly more likely to report inconsistent condom use than those that were never committed, newer, and had not experienced relationship violence. In contrast, relationships in which a condom was used at the first sexual encounter, relationships that were HIV serodiscordant and those where there was paired concurrency were significantly less likely to report inconsistent condom use than those who had not used a condom at their first encounter, were not HIV serodiscordant or were not engaging in paired concurrency. Finally, relationships with dual incarceration and relationships where partners had not injected together were both more likely to report inconsistent condom use, but neither of these effects were significant (Table 3).

Relationship characteristics continued to be strongly associated with inconsistent condom use in the multivariate analysis after adjusting for individual level characteristics. The only individual level characteristic that was associated with inconsistent condom use was injecting drug use; participants who had a history of injecting drugs were more than 5 times more likely to report inconsistent condom use than those without a history of injecting drugs (AOR: 5.28; 95% CI 1.95, 14.24). Inconsistent condom use was higher in relationships that were long-term or medium-term as compared to newer relationships (AOR: 2.51; 95% CI 1.04, 6.06) and (AOR: 2.46; 95% CI 1.10, 5.49). Inconsistent condom use was lower in relationships that had never been committed as compared to relationships which were currently committed (AOR: 0.29; 95% CI 0.16, 0.53). There were no differences in condom use behavior between those who had been committed in the past and those who were currently committed (AOR: 0.49; 95% CI 0.19, 1.23). Furthermore, inconsistent condom use was lower among HIV serodiscordant relationships (AOR: 0.14, 95% CI 0.03, 0.59), relationships in which there was paired concurrency (AOR: 0.37, 95% CI 0.17, 0.81), and in relationships that reported using a condom the first time they had sex together (AOR: 0.09; 95% CI 0.04, 0.22) (Table 4, Model 1).

There was no main effect of dual incarceration on inconsistent condom use. There was, however, a significant interaction between dual incarceration and being in a relationship that was never committed (as opposed to being in a currently committed relationship; AOR: 0.14, 95% CI 0.03, 0.70). The interaction between dual incarceration and being in a relationship that had been committed in the past (as opposed to being in a currently committed relationship) was not significant (AOR: 1.16, 95% CI 0.07, 21.13) (Table 4, Model 2).

Following standard recommendations, we conducted post hoc analyses to determine the simple slopes for the effects of dual incarceration on condom use for never committed and currently committed relationships. These analyses revealed that dual incarceration was not significantly associated with inconsistent condom use among never committed relationships (AOR: 0.60, 95% CI 0.21, 1.68). However, for currently committed relationships, the odds of inconsistent condom use were 4.33 times higher among relationships with a dual incarceration history as compared to relationships where only one partner had an incarceration history (AOR: 4.33, 95% CI 1.02, 18.45).

Discussion

The purpose of this paper was to assess whether dual incarceration influenced condom use behavior among individuals recently involved in the criminal justice system. Relationships where there was dual incarceration had greater HIV risk than relationships where only one individual had been incarcerated. Specifically, dual incarceration increased inconsistent condom use among currently committed relationships, after controlling for both individual and relationship characteristics that might influence condom use. However, dual incarceration did not affect condom use among relationships that had never been committed.

Our focus on how dual incarceration impacts condom use expands on earlier work examining how both an individual’s incarceration and an individual’s sexual partner’s incarceration each affect unprotected sex [7, 11–13, 15, 18]. These earlier studies describe how the movement of one individual in and out of incarceration affects ties within a relationship, and how, in turn, this impacts condom use in the partnership. For example, for some committed couples, the period of incarceration is a time of enhanced emotional connection, often accompanied by a romantic script that both individuals are ‘cleaning up’ their behavior during this time. The emotional closeness, combined with beliefs that both parties have abstained from high risk behavior during the incarceration period, leads couples to eschew condom use post-release as a means of re-establishing physical and sexual intimacy to match the emotional connection they had while separated [18]. For other committed couples, rebuilding relationships following incarceration can be more challenging. For example, one or both parties may have had other sexual partners or engaged in other HIV risk behaviors during the period of incarceration, which may negatively affect their ties and/or their emotional connection to their committed partner [13]. Nevertheless, among these relationships there may also be either a desire not to use condoms or an inability to enforce condom use post-incarceration. That is, couples may not use condoms in order to re-establish ties weakened by or during incarceration or to uphold notions of intimacy and trust even in situations where such applicability may be dubious.

Whereas past research has focused on the impact of individual incarceration on unprotected sex, our study highlights how risk is amplified in committed relationships where both individuals cycle in and out of incarceration. Theorists argue that incarceration disrupts ties [22], and we found that relationships that have more incarceration (i.e., dual incarceration) face greater disruptions and subsequently, less safe sex, than relationships with less incarceration (i.e., single incarceration). Our findings demonstrate the importance of understanding incarceration experiences at the relationship level to fully understand condom use practices within committed relationships.

Furthermore, we found that dual incarceration was not associated with inconsistent condom use among relationships that had never been committed. This suggests that the involuntary mobility associated with incarceration impacts non-committed relationships differently than committed relationships. Specifically, sexual exchange in these relationships may not be as tied to intimacy and trust. As such, it is likely that factors other than incarceration may be driving condom use in these relationships.

There are a number of limitations to our analysis. First, our measures of sexual partner incarceration history and sexual and violence behavior were self-reported by the index participant only and thus prone to reporting error. Future studies should collect data from both index and partner participant to strengthen measurement of relationship characteristics. Second, we only know whether the partner was ever incarcerated. We know nothing about when or how many times the partner was incarcerated. There may be a dose–response relationship such that those relationships in which there are higher numbers of dual incarceration have higher HIV-related risks. Lastly, future research is needed to better understand the process through which dual incarceration impacts risk. Qualitative research with couples who have faced dual incarceration may help us to better understand how they navigate movement of one another in and out of incarceration, how such movement impacts commitment on their relationships and finally, the mechanisms through which such movement impacts their health over time.

Conclusion

Despite these limitations, to our knowledge, our study is the first to show that dual incarceration is associated with inconsistent condom use, which is one marker of HIV risk. The finding that relationships dually disrupted by incarceration may face increased HIV risk above and beyond individual incarceration contribute to a growing body of literature highlighting the negative impacts of mass incarceration on health [2, 19–25]. Addressing upstream determinants of HIV by reducing incarcerations may be one strategy to reduce risk in relationships with higher levels of criminal justice involvement.

References

Kiarie JN, Farquhar C, Richardson BA, Kabura MN, John FN, Nduati RW, et al. Domestic violence and prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV-1. AIDS. 2006;20(13):1763.

Wildeman C, Muller C. Mass imprisonment and inequality in health and family life. Ann Rev Law Soc Sci. 2012;8:11–30.

Council R-EP. Report of the re-entry policy council: Charting the safe and successful return of prisoners to the community: Council of State Governments; 2005.

Grinstead OA, Zack B, Faigeles B, Grossman N, Blea L. Reducing postrelease HIV risk among male prison inmates a peer-led intervention. Crim Just Behav. 1999;26(4):453–65.

Blankenship KM, Smoyer AB. Between spaces: understanding movement to and from prison as an HIV risk factor. In: Sanders B, Thomas YF, Griffin Deeds B, editors. HIV and health: intersections of criminal justice and public health concerns. New York: Springer; 2013. p. 207–21.

Epperson MW, El-Bassel N, Chang M, Gilbert L. Examining the temporal relationship between criminal justice involvement and sexual risk behaviors among drug-involved men. J Urban Health. 2010;87(2):324–36.

Ricks JM, Crosby RA, Terrell I. Elevated sexual risk behaviors among postincarcerated young African American males in the South. Am J Men’s Health. 2015;9(2):132–8.

Clear TR, Rose DR, Waring E, Scully K. Coercive mobility and crime: a preliminary examination of concentrated incarceration and social disorganization. Just Quart. 2003;20(1):33–64.

Clear TR. Imprisoning communities: how mass incarceration makes disadvantaged neighborhoods worse. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2009.

Khan MR, Doherty IA, Schoenbach VJ, Taylor EM, Epperson MW, Adimora AA. Incarceration and high-risk sex partnerships among men in the United States. J Urban Health. 2009;86(4):584–601.

Comfort M. Doing time together: love and family in the shadow of the prison. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2009.

Cooper HL, Caruso B, Barham T, Embry V, Dauria E, Clark CD, et al. Partner incarceration and African–American women’s sexual relationships and risk: a longitudinal qualitative study. J Urban Health. 2015;92(3):527–47.

Harman JJ, Smith VE, Egan LC. The impact of incarceration on intimate relationships. Crim Just Behav. 2007;34(6):794–815.

Swartzendruber A, Brown JL, Sales JM, Murray CC, DiClemente RJ. Sexually transmitted infections, sexual risk behavior, and intimate partner violence among African American adolescent females with a male sex partner recently released from incarceration. J Adolesc Health. 2012;51(2):156–63.

Epperson MW, Khan MR, El-Bassel N, Wu E, Gilbert L. A longitudinal study of incarceration and HIV risk among methadone maintained men and their primary female partners. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(2):347–55.

Hanley JA, Negassa A, Forrester JE. Statistical analysis of correlated data using generalized estimating equations: an orientation. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157(4):364–75.

Institute S. SAS/GRAPH 9.1 Reference: SAS Institute; 2004.

Comfort M, Grinstead O, McCartney K, Bourgois P, Knight K. “You can’t do nothing in this damn place”: sex and intimacy among couples with an incarcerated male partner. J Sex Res. 2005;42(1):3–12.

Blankenship KM, Smoyer AB, Bray SJ, Mattocks K. Black-white disparities in HIV/AIDS: the role of drug policy and the corrections system. J Health Care Poor Unders. 2005;16(4):140.

Adimora AA, Schoenbach VJ, Doherty IA. HIV and African Americans in the southern United States: sexual networks and social context. Sex Transm Dis. 2006;33(7):S39–45.

Adimora AA, Schoenbach VJ, Floris-Moore MA. Ending the epidemic of heterosexual HIV transmission among African Americans. Am J Prev Med. 2009;37(5):468–71.

Thomas JC, Torrone E. Incarceration as forced migration: effects on selected community health outcomes. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(10):1762–5.

Johnson RC, Raphael S. The effects of male incarceration dynamics on acquired immune deficiency syndrome infection rates among African American women and men. J Law Econ. 2009;52(2):251–93.

Pouget ER, Kershaw TS, Ickovics JR, Blankenship KM. Associations of sex ratios and male incarceration rates with multiple opposite-sex partners: potential social determinants of HIV/STI transmission. Public Health Rep. 2010;125(4):70–80.

Binswanger IA, Redmond N, Steiner JF, Hicks LS. Health disparities and the criminal justice system: an agenda for further research and action. J Urban Health. 2012;89(1):98–107.

Acknowledgements

First and foremost, we would like to acknowledge our participants for their willingness to be a part of this research study and to share intimate details about their lives.

Funding

This research study was funded by the U.S. National Institute of Health (R01DA025021; Kim Blankenship, Principal Investigator). This research has also been facilitated by the services and resources provided by the District of Columbia Center for AIDS Research, an NIH funded program (AI117970), which is supported by the following NIH Co-Funding and Participating Institutes and Centers: NIAID, NCI, NICHD, NHLBI, NIDA, NIMH, NIA, FIC, NIGMS, NIDDK, and OAR. Additional support was received from Yale University’s Center for Interdisciplinary Research on AIDS (National Institute of Mental Health Grant No. P30MH062294, Paul D. Cleary, Ph.D., Principal Investigator). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Groves, A.K., Zhan, W., del Río-González, A.M. et al. Dual Incarceration and Condom Use in Committed Relationships. AIDS Behav 21, 3549–3556 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-017-1720-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-017-1720-y