Abstract

HIV places acute stressors on affected children and families; especially in resource limited contexts like sub-Saharan Africa. Despite their importance, the epidemic’s potential consequences for family dynamics and children’s psychological health are understudied. Using a population-based sample of 2,487 caregivers and 3,423 children aged 8–14 years from the Central Province of Kenya, analyses were conducted to examine whether parental illness and loss were associated with family functioning and children’s externalizing behaviors. After controlling for demographics, a significant relationship between parental illness and externalizing behaviors was found among children of both genders. Orphan status was associated with behavioral problems among only girls. Regardless of gender, children experiencing both parental loss and illness fared the worst. Family functioning measured from the perspective of both caregivers and children also had an independent and important relationship with behavioral problems. Findings suggest that psychological and behavioral health needs may be elevated in households coping with serious illness and reiterate the importance of a family-centered approach for HIV-affected children.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The psychological wellbeing of children affected by HIV and AIDS has received increased attention over the last decade. Mental health disparities are well-documented among children affected by HIV and AIDS [1–3]. However, significant gaps remain in our understanding of how HIV and AIDS impacts children and families, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa where the epidemic is most profound.

Orphanhood and internalizing disorders predominate in the literature concerning the psychological health of HIV-affected children. Less empirical attention has been given to children living with a chronically ill caregiver or other household member, or to behavioral manifestations of distress. A recent literature review on the psychological impact of HIV and AIDS on children identified 29 studies measuring emotional adjustment, yet only 15 examining behavioral adjustment [3]. Among the 18 reviewed studies from sub-Saharan Africa, only three included children coping with parental illness [3]. Moreover, few studies go beyond assessing the impact of death and illness to address other risk and protective factors [2], especially those factors that may promote resilience [4, 5].

One major determinant of psychological wellbeing in children is the way a family functions, which may include aspects related to cohesion, conflict, communication, and problem-solving [6, 7]. Empirical research from around the world has repeatedly demonstrated that family functioning can ameliorate negative child psychological outcomes and promote resilience, particularly among children in families coping with chronic stressors or significant life events [8–12]. Family functioning may similarly mitigate the effects of HIV and AIDS on children’s psychological outcomes. Indeed, one study from Europe of children whose mothers were living with HIV reported family functioning as the strongest predictor of children’s behavioral and emotional problems. The significance of family functioning even superseded factors including communication and disclosure about HIV status in the family, parental support networks, perceived discrimination, and substance use [13]. A recent review showcases growing knowledge about the impact of maternal HIV infection on parenting [14]; however, less is known about the impact on broader family dynamics. Understanding family functioning in sub-Saharan Africa—the epicenter of the epidemic—may reveal significant pathways to risk, and most importantly, factors that are amenable to change.

Using a population-based sample from Kenya, this study assesses how parental illness and loss may be linked to family functioning and children’s externalizing behaviors. Analyses examine children’s outcomes separately by gender, addressing a significant gap in the literature to date [3, 15].

Methods

Study Setting

This study took place in the Central Province of Kenya, within the Kamwangi Division of Gatundu District (formerly part of Thika District). The study site was a rural environment with 22,607 households located 40 km from Nairobi, the country’s urban capital city [16]. While Kenya’s overall HIV prevalence of 6.1 % is lower than many other sub-Saharan countries, it faces a concentrated sub-epidemic in a generalized epidemic setting [17]. Moreover, the district where this study took place has a history of elevated HIV prevalence, as high as 31 % among antenatal surveillance sites in 1998 [18].

Study Sample and Procedures

Data collection occurred in two purposively selected rural areas of Kamwangi Division—Mang’u and Githobokoni. Within each of these communities, three census-defined locations were randomly selected for inclusion in the survey, inclusive of 40 villages. With assistance from local authorities, the research team enumerated all households within the study areas, totaling 6,224 households. Enumerated households were screened for eligibility, and those with a child aged 8–14 were invited to participate in the survey.

In all eligible households, the research team attempted to conduct face-to-face interviews with up to two children age 8–14 and their primary caregiver, defined as the person in the household who held principal responsibility for the day-to-day care of that child. If more than two age-eligible children lived in the household, two were randomly selected to participate in the survey. Of the 6,224 households identified and approached, 57 % were ineligible (i.e., did not have a child aged 8–14), 2 % were not home after three visits, and less than 1 % refused to participate. The final sample included 2,487 caregivers and 3,423 children.

The full research protocol and all instruments were approved by the institutional review boards at Tulane University in the United States and Kenyatta National Hospital in Kenya. Participants were informed orally of the purpose and nature of the study, as well as its expected risks and benefits. Because of the high illiteracy rate, verbal consent was requested. Adults provided consent for themselves and the children under their care. Assent was also obtained from children, using age-appropriate language to promote comprehension.

Measures

Primary predictors of interest included parental illness and loss. Information on parental illness and survival was gathered from the child’s primary caregiver. Children with one or more deceased parents were considered orphans, consistent with the globally recognized definition of orphanhood [19]. Parents were also coded as deceased if they had been absent for two or more years and their survival status was unknown. Parental illness was defined as having a serious illness for at least three months in the past 12 months, based on self-report, a marker that has been used as a proxy for potential HIV infection [20]. Children were classified into one of four mutually exclusive parental status categories: orphan only, living with a sick parent only, dually affected, or both parents alive and healthy.

Externalizing behaviors were reported by the caregiver using the 20-item total difficulties subscale of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (alpha .74), which includes measures of conduct, hyperactivity, emotional and peer relationship problems [21, 22]. Mean scores were calculated, with a possible range of 0–33, where higher scores reflect greater behavioral problems (mean = 11.08, standard deviation = 5.61).

Measures of family functioning were gathered from both the caregiver and child perspective, in alignment with recommendations for capturing a comprehensive representation of family dynamics [6]. Scales included statements pertaining to support, communication, openness and problem-solving capacities, as well as trust and acceptance within the family. The child-reported measure of family functioning was the six-item family self-esteem subscale of the Multidimensional Self-Esteem Questionnaire (alpha 0.76) [23]. Results range from one to four, and higher scores are indicative of better family functioning (mean = 3.58, standard deviation = .46). Caregivers also reported on general family functioning applying the eight-item subscale of the same name within the McMaster Family Assessment Device (alpha 0.89) [24]. These results also range from one to four, but higher scores reflect worse family functioning (mean = 1.78, standard deviation = .58).

The survey also collected information on demographics including: child and caregiver age and gender; caregiver’s educational attainment and marital status; and number of children in the household. Caregivers also reported on household infrastructure and assets and these data were used to divide the sample into wealth quintiles. Households with two or fewer assets were classified as extremely poor.

Analyses

Basic frequencies (for categorical variables) and means (for continuous variables) were used to characterize the sample. An initial t test was performed to identify significant differences in the prevalence of externalizing behaviors by gender. Simple linear regression examined the unadjusted relationship between parental status (survival or illness) and both measures of family functioning. Multivariate regression models were created to explore the association between parental status and externalizing behavior, adjusting for the child, caregiver and household demographics described above. A second set of multivariate models further incorporated the two family functioning variables as predictors of externalizing behavior. t tests were conducted to compare the beta coefficients associated with parental status in both multivariate models, in order to assess whether family functioning might mediate the relationship between parental status and child behavior. Regression analyses adjusted standard errors for clustering at the level of the caregiver. All analyses were conducted in Stata 13.0.

Results

Description of the Sample

Approximately 40 % of children in the sample were affected by loss or illness: about 28 % of the sample was comprised of children in the “orphan only” group, 10 % of children were living with a sick parent and 3 % were dually affected. Among orphans, paternal loss was most common: 76 % had lost only their father, 7 % had lost only their mother and the remaining 17 % had lost both parents. Among children experiencing parental illness, more than half had only an ill mother (51 %), 35 % had only an ill father, and 13 % had parents who were both ill.

Table 1 provides an overview of key socio-demographics in the sample, stratified by children’s parental status: orphaned, ill parent(s), dually affected, or unaffected by parental illness or death. Children’s age and gender was largely equivalent across groups. Nearly one-quarter of dually affected children and one-fifth of orphans had changed homes in the last year, compared to less than 15 % of the other children. Children were typically cared for by a female; most of these caregivers had attended school (89 %) and were between 30 and 49 years old (71 %). However, caregivers of orphans and dually affected children tended to be older and single, and fewer had attended school or were married. Extreme poverty was also more common in these homes, especially in dually affected households.

Children’s Behavior and Family Functioning

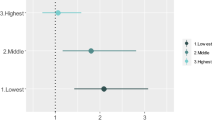

The t test analysis demonstrated a significant difference in the mean externalizing behavior scale scores between boys and girls (boys = 11.60, girls = 10.57, test statistic = 5.40, p = .000), therefore this outcome was analyzed separately by gender. As seen in Table 1, the mean scores on externalizing behavior for children of both genders typically rose when moving across the spectrum from unaffected to dually affected children. Table 2 displays a similar pattern with respect to mean scores of the family functioning variables, and simple linear regression results confirm differences by parental status. With exception of the trend for dually affected girls, all types of affected children had a significantly greater likelihood of caregiver-reported poor family functioning and child-reported lower family self-esteem than unaffected children (see Table 2). Table 3 displays gender-specific multivariate models predicting externalizing behavior, with and without the family functioning variables. After controlling for demographics, a consistent relationship was apparent between parental illness and heightened behavioral problems for both girls and boys (girls: coefficient 1.65, test statistic = 3.48, p = .001; boys: coefficient 1.53, test statistic = 2.88, p = .004). Only orphaned girls had an elevated prevalence of externalizing behaviors; this pattern was absent among boys (girls: coefficient 1.61, test statistic = 3.05, p = .002; boys: coefficient −.09, test statistic = −.17, p = .867). Regardless of gender, children who were both orphaned and living with a sick parent fared the worst (girls: coefficient 3.36, test statistic = 3.27, p = .001; coefficient 3.24, test statistic = 3.69, p = .000). These patterns persisted when the family functioning variables were added to the model.

Family functioning from both the child and caregiver perspective was associated with child behavioral problems for children of both genders (girls: family functioning coefficient 2.05, test statistic = 8.36, p = .000; family self-esteem coefficient −1.40, test statistic = −4.14, p = .000; boys: family functioning coefficient 2.30, test statistic = 9.40, p = .000; family self-esteem coefficient −1.07, test statistic = −3.43, p = .001). With the exception of dually affected children, who demonstrated the highest risk, the magnitude of associations for the family functioning and parental status variables with externalizing behavior were fairly similar, illustrating their equivalent importance to externalizing behaviors (see Table 3). Analysis yielded no evidence that family functioning mitigated the impact of parental status on child behavior. Specifically, t tests for mediation showed no significant change in any of the beta coefficients associated with parental status when family self-esteem and family functioning were added to the model (t statistics ranged from −0.01 to 0.61). Results suggest that both parental status and family functioning have an important and independent relationship to children’s externalizing behaviors.

Discussion

Results from this study demonstrate heightened risk of behavioral problems among orphans and children living with chronically ill parents in Kenya. Parental illness was associated with greater problem behaviors for children of both genders. For boys, parental illness was associated with behavioral issues, whereas orphanhood was not. Children who had endured both parental illness and the loss of a parent faced the greatest risk.

Few studies concerning the psychological impact of HIV and AIDS on children in sub-Saharan Africa have given due attention to parental illness, instead concentrating primarily on orphans [3]. Yet, orphanhood may—at least in part—be a proxy for ongoing exposure to chronic illness in the household [25]. Children are often classified as an orphan even if they have lost only one parent [26]. The majority of orphans in sub-Saharan Africa are single orphans and given the nature of the epidemic, the surviving parent is highly likely to be living with HIV [27, 28]. Our findings make evident the importance of accounting for both parental illness and loss in discerning risk for behavioral problems, consistent with prior results concerning internalizing disorders from South Africa [29].

Many of the pathways potentially linking orphanhood and psychological distress would be equally applicable to children living with ill parents. Both orphanhood and familial chronic illness may be accompanied by increased economic and caregiving responsibility, community stigma, educational interruptions, and impoverishment—all of which contribute to psychological distress in children [25, 30–33]. Parental illness may also engender additional risk factors, such as child maltreatment, neglect of children’s emotional needs and decreased supervision [34, 35]. Children may also face uncertainty about the continuity of care—particularly if they have already experienced the loss of one parent. Psychological studies of AIDS-affected children that focus only on parental mortality may miss the impact of the preceding period of illness, when family stressors are acute.

These findings add to the limited body of existing research from sub-Saharan Africa concerning the potential consequences of HIV and AIDS on family dynamics and its importance to child wellbeing. Results illustrate the significance of family functioning for children’s externalizing behaviors, in accordance with a prior study among HIV-affected children in Europe [14]. Through inclusion of a population-based sample, this study also demonstrates the relatively higher prevalence of dysfunction among families affected by HIV or other serious chronic conditions, measured from both the child and caregiver perspective. HIV and AIDS are widely recognized as having the potential to destabilize family and community systems, yet both research and interventions tend to concentrate on individuals rather than the family unit [36, 37]. It is hoped that these results will spur greater attention to family dynamics as an important entry point for mitigating the psychological consequences of HIV and AIDS on children. This recommendation is consistent with wider appeals to embrace a family-centered approach for the care of children affected by the epidemic [13, 36–38].

A key limitation of this study relates to our inability to differentiate between various causes of chronic illness, and in particular AIDS-related illness. Relying on self-report of HIV and AIDS can be unreliable, given the associated stigma and other potential consequences of disclosure. In this study, respondents reported whether or not they had a chronic illness lasting three of the last 12 months. Given the high prevalence of infection among adults of reproductive age in the area where the research occurred, self-reported chronic illness is presumed to reflect HIV or AIDS in many if not most cases. The focus on parental illness, rather than caregiver illness more generally, likely excludes non-HIV related chronic illnesses that commonly affect the elderly. Other studies have used verbal autopsies to distinguish AIDS-related illnesses from other conditions [29, 39, 40]. However, a limitation with that approach is the exclusion of asymptomatic individuals. With increased access to antiretroviral medication across sub-Saharan Africa, symptoms may not be the most appropriate method for detecting HIV and AIDS. Asymptomatic HIV-positive individuals may still experience financial and social consequences of the disease; methods to ensure their inclusion and proper categorization in research are as important as precision in disease determination. The use of biological markers is the most reliable approach for determining HIV status, but poses considerable cost, ethical and feasibility considerations in population-based studies [41, 42]. Finally, another limitation of this study is its cross-sectional design, which precludes conclusions concerning directionality; for example, child behavioral problems could have a casual impact on family functioning or vice versa. Prior longitudinal research suggests that a complex bi-directional relationship likely exists between family dysfunction and child behavioral problems [43].

Conclusion

This study draws attention to parental illness as a risk factor for externalizing behaviors in children, and suggests that greater attention to psychological wellbeing in this population is warranted. The expansion of HIV treatment in resource-poor settings will result in fewer orphans, but potentially a greater number of children and families coping with illness, and over longer time periods. Even now, orphanhood is only the tip of the iceberg: for instance, in sub-Saharan Africa in 2012 an estimated 1.2 million people died of AIDS, whereas 22.1 million people of reproductive age remain HIV-infected [44]. Greater understanding of the impact of parental illness will help to better tailor program efforts to the unique needs of these children and families. Attention to factors that may promote resiliency and mitigate risk are equally important. To our knowledge, this is the first study to consider the role of family functioning on children’s psychological health in the context of HIV and AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa. Attention to family relationships provides a more nuanced representation of child wellbeing, and a target for prevention and risk management. Future research among children in households affected by HIV and AIDS should investigate the potential protective nature of family functioning and test interventions designed to strengthen family interactions.

References

Wild L. The psychosocial adjustment of children orphaned by AIDS. South Afr J Child Adolesc Mental Health. 2001;13(1):3–25.

Cluver L, Gardner F. The mental health of children orphaned by AIDS: a review of international and southern African research. J Child Adolesc Mental Health. 2007;19(1):1–17.

Chi P, Li X. Impact of parental HIV/AIDS on children’s psychological well-being: a systematic review of global literature. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(7):2554–74.

Skovdal M. Pathologising healthy children? A review of the literature exploring the mental health of HIV-affected children in sub-Saharan Africa. Transcult Psychiatry. 2012;49(3–4):461–91.

Betancourt TS, Meyers-Ohki SE, Charrow A, Hansen N. Annual research review: mental health and resilience in HIV/AIDS-affected children: a review of the literature and recommendations for future research. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2013;54(4):423–44.

Pedersen S, Revenson TA. Parental Illness, family functioning, and adolescent well-being: a family ecology framework to guide research. J Fam Psychol. 2005;19(3):404–19.

Davies PT, Cummings EM, Winter MA. Pathways between profiles of family functioning, child security in the interparental subsystem, and child psychological problems. Dev Psychopathol. 2004;16:525–50.

Pakenham KI, Cox S. Test of a model of the effects of parental illness on youth and family functioning. Health Psychol. 2012;31(5):580–90.

Rotheram-Borus MJ, Stein JA, Lester P. Adolescent adjustment over six years in HIV-affected families. J Adolesc Health. 2006;39(2):174–82.

Edwards B, Clarke V. The psychological impact of a cancer diagnosis on families: the influence of family functioning and patients’ illness characteristics on depression and anxiety. Psycho-Oncology. 2004;13(8):562–76.

Gorman-Smith D, Henry DB, Tolan PH. Exposure to community violence and violence perpetration: the protective effects of family functioning. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2004;33(3):439–49.

Shek DTL. Family functioning and psychological well-being, school adjustment, and problem behavior in chinese adolescents with and without economic disadvantage. J Genet Psychol. 2002;163(4):497.

Nöstlinger C, Bartoli G, Gordillo V, Roberfroid D, Colebunders R. Children and adolescents living with HIV positive parents: emotional and behavioural problems. Vulnerable Child Youth Stud. 2006;1(1):29–43.

Spies R, Sterkenburg PS, Schuengel C, van Rensburg E. Linkages between HIV/AIDS, HIV/AIDS-psychoses and parenting: a systematic literature review. Vulnerable Child Youth Stud. 2013;9(2):174–92.

Sherr L, Mueller J, Varrall R. Evidence-based gender findings for children affected by HIV and AIDS: a systematic overview. AIDS Care. 2009;21(Supplement 1):83–97.

Kenya Central Bureau of Statistics. National population census. Nairobi: Kenya Central Bureau of Statistics; 1999.

NACC, NASCOP. Kenya AIDS Epidemic update 2011. Nairobi: The Kenya National AIDS Control Council (NACC) and the National AIDS and STI Control Programme (NASCOP); 2012.

NASCOP, Kenya Ministry of Health. AIDS in Kenya. Nairobi: National AIDS and STI Control Programme (NASCOP); 2005.

United Nations Children’s Fund U. The Framework for the protection, care and support of orphaned and vulnerable children living in a world with HIV and AIDS. New York: UNICEF, 2004 Contract No.: Report.

United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Guidance document. Developing and operationalizing a national monitoring and evaluation system for the protection, care and support of orphans and vulnerable children living in a world with HIV and AIDS. 2009 [cited 2010]. Available from: www.unicef.org/aids/files/OVC_MandE_Guidance_FINAL.pdf. Accessed 3 Sept 2014.

Goodman R. The strengths and difficulties questionnaire: a research note. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1997;38(5):581–6.

Goodman R. Psychometric properties of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40(11):1337–45.

Dubois DL, Felner RD, Brand S, Phillips RSC, Lease AM. Early adolescent self-esteem: a developmental-ecological framework and assessment strategy. J Res Adolesc. 1996;6(4):543–79.

Epstein NB, Baldwin LM, Bishop DS. The McMaster family assessment device. J Marital Fam Ther. 1983;9(2):171–80.

Cluver L, Operario D, Gardner F. Parental illness, caregiving factors and psychological distress among children orphaned by acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) in South Africa. Vulnerable Child Youth Stud. 2009;4(3):185–98.

Sherr L, Varrall R, Mueller J, Richter L, Wakhweya A, Adato M, et al. A systematic review on the meaning of the concept ‘AIDS Orphan’: confusion over definitions and implications for care. AIDS Care. 2008;20(5):527–36.

United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Africa’s orphaned and vulnerable generations: children affected by AIDS. New York: The United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF); 2006.

Dunkle KL, Stephenson R, Karita E, Chomba E, Kayitenkore K, Vwalika C, et al. New heterosexually transmitted HIV infections in married or cohabiting couples in urban Zambia and Rwanda: an analysis of survey and clinical data. Lancet. 2008;371(9631):2183–91.

Cluver LD, Orkin M, Boyes ME, Gardner F, Nikelo J. AIDS-orphanhood and caregiver HIV/AIDS sickness status: effects on psychological symptoms in South African youth. J Pediatr Psychol. 2012;37(8):857–67.

Cluver L, Orkin M. Cumulative risk and AIDS-orphanhood: interactions of stigma, bullying and poverty on child mental health in South Africa. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69(8):1186–93.

Nyamukapa CA, Gregson S, Wambe M, Mushore P, Lopman B, Mupambireyi Z, et al. Causes and consequences of psychological distress among orphans in eastern Zimbabwe. AIDS Care. 2010;22(8):988–96.

Robson E, Ansell N, Huber U, Gould W, van Blerk L. Young caregivers in the context of the HIV/AIDS pandemic in sub-Saharan Africa. Popul Space Place. 2006;12(2):93–111.

Skovdal M. Children caring for their “caregivers”: exploring the caring arrangements in households affected by AIDS in Western Kenya. AIDS Care. 2010;22(1):96–103.

Rajaraman D, Earle A, Heymann SJ. Working HIV care-givers in Botswana: spill-over effects on work and family well-being. Community Work Fam. 2008;11(1):1–17.

Cluver L, Orkin M, Boyes ME, Sherr L, Makasi D, Nikelo J. Pathways from parental AIDS to child psychological, educational and sexual risk: developing an empirically-based interactive theoretical model. Soc Sci Med. 2013;87:185–93.

Irwin A, Adams A, Winter A. Home truths: facing the facts on children, AIDS, and poverty. Joint Learning Initiative on Children and HIV/AIDS, 2009.

Richter L. An introduction to family-centred services for children affected by HIV and AIDS. J Int AIDS Soc. 2010;13(Suppl 2):S1.

Richter L, Beyrer C, Kippax S, Heidari S. Visioning services for children affected by HIV and AIDS through a family lens. J Int AIDS Soc. 2010;13(Suppl 2):S2.

Hosegood V, Vanneste A-M, Timaeus IM. Levels and causes of adult mortality in rural South Africa: the impact of AIDS. AIDS. 2004;18(4):663–71.

Tollman SM, Kahn K, Sartorius B, Collinson MA, Clark SJ, Garenne ML. Implications of mortality transition for primary health care in rural South Africa: a population-based surveillance study. Lancet. 2008;372(9642):893–901.

Pappas G, Hyder AA. Exploring ethical considerations for the use of biological and physiological markers in population-based surveys in less developed countries. Glob Health. 2005;1:16–7.

MacLachlan EW, Baganizi E, Bougoudogo F, Castle S, Mint-Youbba Z, Gorbach P, et al. The feasibility of integrated STI prevalence and behaviour surveys in developing countries. Sex Transm Infect. 2002;78(3):187–9.

Neece CL, Green SA, Baker BL. Parenting stress and child behavior problems: a transactional relationship across time. Am J Intellect Dev Disabil. 2012;117(1):48–66.

UNAIDS. Global Report: UNAIDS report on the global AIDS epidemic 2013. Geneva: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS; 2013.

Acknowledgments

This study was made possible through funds from the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief provided from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) under a Cooperative Agreement (GPO-A-00-03-00003-00) with MEASURE Evaluation. The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States government. In addition to our donors, we extend our appreciation to the research team from Population Studies Research Institute of the University of Nairobi, particularly Wanjiru Gichuhi who helped lead the fieldwork, along with the field, data entry and administrative staff who all helped to ensure data quality. We further acknowledge the logistical support provided by Kristen Neudorf and staff and volunteers from Integrated AIDS Project and Pathfinder International who operated programs in the region. We are also grateful for the review and useful editorial suggestions from Tory Taylor. Most importantly, we appreciate the children and caregivers who participated in this study and ultimately increased our understanding of their circumstances.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Thurman, T.R., Kidman, R., Nice, J. et al. Family Functioning and Child Behavioral Problems in Households Affected by HIV and AIDS in Kenya. AIDS Behav 19, 1408–1414 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-014-0897-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-014-0897-6