Abstract

Within Mozambique’s current HIV care system, there are numerous opportunities for a person to become lost to follow-up (LTFU) prior to initiating antiretroviral therapy (pre-ART). We explored pre-ART LTFU in Zambézia province utilizing quantitative and qualitative methods. Patients were deemed LTFU if they were more than 60 days late for either a scheduled appointment or a CD4+ cell count blood draw, according to national guidelines. Among 13,968 adult patients registered for care, 211 (1.8 %) died, one transferred, 2,196 (15.7 %) initiated ART, and 9,195 (65.8 %) were LTFU during the first year. Being male, younger, less educated, and/or having no home electricity were associated with LTFU. Qualitative interviews revealed that poor clinical care, logistics and competing priorities contribute to attrition. In addition, many expressed fears of stigma and/or rejection by family or community members because they were HIV-infected. At 66 %, pre-ART LTFU in Zambézia, Mozambique is a significant problem. This study highlights characteristics of lost patients and discusses barriers requiring consideration to improve retention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The advent of combination antiretroviral treatment regimens (ART) has transformed the lives of people living with HIV infection, changing it from a near-certain death sentence to a chronic illness needing clinical management. However, not all individuals who are HIV-infected are immediately eligible for treatment. In 2013, the World Health Organization (WHO) changed their treatment guidelines, recommending that adults initiate treatment when CD4+ cell counts drop to 500 cells/mm3 or below, with the 2010 guidelines recommending treatment initiation when CD4+ cell counts dropped to 350 cells/mm3 or below [1, 2]. Persons having higher CD4+ cell counts not yet eligible to initiate ART in accordance with guidelines are eligible for other services consisting of the following: (1) clinical visits for opportunistic infection screening, antenatal care (when applicable), immunizations, nutritional assessment/supplementation (when applicable), acute/chronic disease condition screening (malaria, tuberculosis, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, etc.), and the initiation of prophylactic medications (i.e. cotrimoxazole for prevention of enteric/respiratory bacterial infections and isoniazid for tuberculosis prevention among eligible persons); and (2) routine laboratory visits (CD4+ cell count monitoring).

Numerous national public initiatives offering first-line combination antiretroviral therapy (ART) for HIV infection have commenced in sub-Saharan Africa since 2002 [3]. In the African region, which continues to bear the brunt of the HIV epidemic, more than 7.5 million persons were receiving potentially life-saving treatment at the end of 2012, compared to 50,000 persons a decade earlier [4]. Analyses from the region report favorable clinical/treatment outcomes and impressive declines in AIDS-related mortality among HIV-infected adults and children receiving ART [3]. While immunologic recovery, virologic suppression and ART adherence rates are on par with resource-replete settings, loss to follow-up (LTFU) and high mortality rates, especially within the first 6 months of treatment, remain a significant problem [3]. In fact, LTFU has emerged as a challenge to the provision of clinical care, with upwards of 60 % of all patients enrolled in HIV care becoming LTFU very early in the HIV care continuum, specifically before initiating combination ART (i.e. in the pre-ART window) in Africa and other regions [5–7]. Suboptimal patient adherence and retention has also been a challenge in resource-replete settings [8]. Retention in care improves survival outcomes; therefore, a better understanding of the factors impacting LTFU has the true potential to improve the well-being and longevity of these at-risk persons [8]. Studies conducted in resource-limited settings have shown the benefits on retention of initiating ART at higher CD4+ cell counts, namely<350 cells/mm3 compared to <200 cells/mm3 [9–11]. The HPTN 052 study team [10, 12] also documented improved clinical outcomes (reduced morbidity and mortality) in individuals initiating ART at higher CD4+ cell counts (350–550 vs. <250 cells/mm3). Recently published evidence in Mozambique suggests that older, higher weight, more educated, and sicker (i.e. having more advanced WHO clinical stage disease) patients are less likely to be LTFU among those not eligible for ART [13]. One study evaluating HIV-infected adults in sub-Saharan Africa suggested that being male, being less immunosuppressed (having a higher CD4+ count) and having received fewer years of formal education was associated with delays in care during this critically important pre-ART window [14]. Delays in ART initiation ultimately lead to increased morbidity and mortality in resource-constrained settings, and as evidence shows, missed opportunities for treatment to serve as prevention of new infections [15, 16]. All of this highlights the pressing need to identify the factors influencing pre-ART LTFU.

Mozambique’s adult HIV prevalence of 11.5 % (2009) is among the highest in sub-Saharan Africa [17]. Since 2006, Vanderbilt University (VU) and its affiliate non-governmental organization, Friends in Global Health (FGH), have collaborated with the Mozambican government to improve access to HIV/AIDS care and treatment in the country’s second most populous province, Zambézia (2009 estimated HIV prevalence of 12.6 %) [17]. VU/FGH has provided technical assistance through the United States government’s President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), leading to increases in availability and quality of comprehensive HIV care services, including ART, in as many as 12 districts within Zambézia.

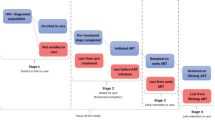

There are numerous ways for a patient to become LTFU before initiating ART; the cumulative number of persons lost prior to ART initiation is substantial [5]. In Mozambique, patients LTFU can be classified into one of three groups: (1) those testing HIV positive who opened a clinical record but did not return for a clinical evaluation [18]; (2) those who after an initial clinical consultation did not return for a CD4+ count blood draw, and/or (3) those who did have a CD4+ count drawn but who did not return to receive their results; all three fit into the definition as put forth by the Ministry of Health [19]. These intermediate steps (between testing and ART initiation) comprise a well-described “leaky cascade” that captures challenges to providing adequate HIV care to populations [20].

The goal of this study was to evaluate pre-ART LTFU in Zambézia province, Mozambique using mixed methods. Utilizing data from the VU/FGH electronic medical records system existing in ten supported districts, we estimated rates of pre-ART LTFU and examined what distinguished patients LTFU from those who remained in care. As a corollary, in one of the supported districts we conducted qualitative interviews of a small group of patients who had missed pre-ART care appointments but were not yet LTFU to qualitatively explore possible reasons why patients are not returning for care.

Methods

Quantitative

Study Population

This was an observational cohort study using routinely collected patient-level data. Details of our clinical program have been reported previously [21]. We included all HIV-infected patients aged 18 years or older registering at an HIV care center in VU/FGH-supported clinics from January 1, 2010 to June 30, 2011. We excluded patients <18 years old and patients enrolled into care outside the defined study period, as well as patients transferring in during the period. The study period was selected because the electronic medical record across districts prior to January 2010 had differing documentation standards and capacities; also, we wanted to assess 1-year outcomes. VU/FGH-supported clinics at the time of the study were located in 12 districts, 10 of which had implemented electronic databases using either Microsoft Access® or OpenMRS™ to collect patient-level information. The databases contained only information extracted from Ministry-standardized paper forms completed by Ministry of Health clinical providers, and entered by facility-based FGH data entry personnel following clinical appointments. Only information from the HIV care and treatment service was included in the database; data from HIV-related services (e.g., antenatal care, tuberculosis) were not included. The data were completely de-identified during extraction from the database so as to not have any means of identifying individual patients.

Statistical Analysis

Patients were classified as pre-ART LTFU if they were more than 60 days late for either a scheduled appointment or a CD4+ cell count blood draw, according to national guidelines. Cumulative incidence estimates treating death, transfer and ART initiation as competing risks were used to compute 1 year LTFU. Two Cox regression models stratified by district estimated the association between time to pre-ART LTFU and baseline covariates. The first model considered only those characteristics routinely collected at registration for all patients in the study: age, sex, marital status, occupation, educational level, referral site, the presence (or absence) of home electricity (proxy for economic status), and body mass index (BMI). A second model was built from the subset of the population with at least one CD4+ count and included clinical variables: hemoglobin, CD4+ count, and WHO clinical stage. Patients who initiated ART, died, or were transferred to another site were censored at the earliest date of these events (dropped from the risk set). Covariates were selected a priori; however, predictors were dropped from multivariable analysis if there was excessive missing data (>50 %). To relax linearity assumptions, age, BMI, and CD4+ count were included in the models using restricted cubic splines [22]. Missing values of baseline predictors with <50 % missing data were accounted for using multiple imputation techniques to prevent case-wise deletion. We used predictive mean matching to take random draws from imputation models 10 times [23]. We employed R-software 2.15.1 (www.r-project.org) for all analyses. Analysis scripts are available at http://biostat.mc.vanderbilt.edu/ArchivedAnalyses.

Qualitative

Study Population

The district of Maganja da Costa was purposively selected because it is a medium-sized district with a growing HIV/AIDS care and treatment service, versus districts that started ART care earlier and are more densely populated, and those districts with smaller treatment programs and more disperse populations [24]. As with some of the other districts working with VU/FGH, the district of Maganja da Costa also has an active association of persons living with HIV/AIDS that is engaged with VU/FGH in the active case finding of late and defaulting patients. As part of routine care, patients providing consent for home visits who were late for a scheduled appointment received home visits from trained community volunteers of local HIV/AIDS associations. While other districts also conducted home visits, visits to pre-ART patients were curtailed during the study period as a result of funding shortages. Adult pre-ART patients in danger of becoming LTFU in the district of Maganja da Costa who had missed an appointment within the previous 60 days were eligible for inclusion. Volunteer community association members received a 2-day training comprised of research ethics, informed consent, the purpose of the study, as well as basic qualitative interviewing techniques and practical training on conducting the interviews.

The study’s qualitative component explored why enrolled patients were not returning for pre-ART care. A 34-question semi-structured interview containing open and close-ended questions was modeled after similar retention research instruments previously utilized in sub-Saharan Africa [25]. Questions explored barriers to care such as logistical challenges, competing priorities, and social attitudes towards HIV.

All eligible patients were provided oral and written information about the study and gave written informed consent prior to participating in the interview. During a 2-week period, we interviewed 20 patients who had missed appointments at the health facility, agreed to be interviewed, and provided informed consent. Interviewers had copies of the questionnaire and consent form in both Portuguese and the local language (Nyaringa). Following the interview, with patient consent, data on clinical status of the patient, including basic demographic information, referral location, and health status including age, height, weight, tuberculosis status, and CD4+ count if applicable, were extracted by an FGH employee from the participants’ clinical record at the health facility.

Notes from the interviews were translated to Portuguese and entered into a Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) database (http://www.project-redcap.org/), along with data gathered from the clinical files. Inductive and deductive coding was used for analysis.

Ethics

Study protocols were reviewed and approved by both the National Committee of Bioethics and Health in Mozambique and the Institutional Review Board of Vanderbilt University’s School of Medicine prior to study initiation.

Results

Quantitative Analysis

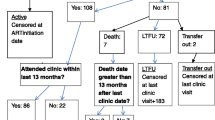

Of the 13,968 patients registered for HIV care during the study period, 212 (1.8 %) died, one (0.1 %) transferred, 2,196 (15.7 %) initiated ART, 2,365 (16.9 %) remained pre-ART, and 9,195 (65.8 %) were LTFU 12 months following enrollment (Table 1). The study pre-ART population was predominately female (70 %) with a median age of 28 years. Source of referral to HIV care was mostly voluntary counseling and testing (VCT) (47 %) and prevention of mother-to-child-transmission (PMTCT) programs (27 %). The CD4+ count results at enrollment were not documented in 62 % of pre-ART LTFU patients’ records, compared with only 12 % of those alive and in pre-ART care at 1 year. The most common occupations were subsistence farmer (37 %) and domestic work (40 %). Figure 1 shows the distribution of those patients who die, transfer, initiate ART or are LTFU in the first year.

We examined the associations between patient characteristics and pre-ART LTFU among 13,968 patients enrolled into HIV care using Cox regression (Table 2, column 2). Men had a 32 % higher hazard of LTFU than women. Compared with persons aged 30, 20 year-olds had a higher likelihood of being lost [adjusted hazard ratio (aHR) (95 % CI) 1.23 (1.18–1.29)]. Widows/widowers had better retention than married individuals [aHR (95 % CI) 0.89 (0.81–0.99)]. Compared to subsistence farmers, administrative workers had half the hazard of LTFU, and small merchants and domestic workers had a slightly higher hazard (p = 0.006). Persons with lower education had higher risk of LTFU, while persons from a home with electricity had 23 % lower hazard of LTFU [aHR (95 % CI) 0.77 (0.70–0.85)]. Source of referral to HIV care was significantly associated with LTFU (p < 0.001). Compared to VCT, patients referred from blood bank/laboratory, medical inpatient wards, and/or PMTCT settings had significantly higher risk of LTFU. Patients with lower BMI at enrollment had higher risk of LTFU [aHR (95 % CI) 16.0 vs. 18.5 kg/m2: 1.15 (1.10–1.21)], although this variable had many missing values (31 %). When including all patients (n = 13,968) pre-ART LTFU and evaluating by district (Fig. 2a), there were differences in pre-ART LTFU rates by district, especially in the first few months after being enrolled in care.

Estimates of pre-ART LTFU by district in 1 year following enrollment into HIV care, Zambézia province, Mozambique. a, b Displays prominent jumps which represent the scheduled for CD4+ count blood draws; all patients should have a CD4+ count drawn every 3 months in addition to regular clinic visits (generally monthly). a All pre-ART patients (n = 13,968), b contains all pre-ART patients with at least one CD4+ count (n = 7,603)

A second Cox regression modeled the association between patient characteristics, health status, and pre-ART LTFU among 7,603 (38 %) patients enrolled into HIV care with at least one CD4+ count (Table 2, column 3). Among this subset of patients, similar risk factors were observed. Additionally, increases in hemoglobin were associated with lower risk of LTFU [aHR (95 % CI) per 1 g/dL: 0.87 (0.82–0.91)]. Compared to patients having a baseline CD4+ count of >350 cells/mm3, patients having a CD4+ count of >50 cells/mm3 had a 41 % higher hazard of pre-ART LTFU and patients having a CD4+ count of >500 cells/mm3 had a 5 % higher hazard (p < 0.001). Patients with WHO clinical stage II or III disease had a 11–19 % lower hazard of LTFU compared to those having WHO clinical stage I disease (p < 0.001). When evaluating only pre-ART patients having at least one CD4+ count drawn/obtained (n = 7,603), one observes differences in pre-ART LTFU by district (Fig. 2b). In this sub-analysis, patients cared for in the districts of Maganja da Costa, Gilé, and Inhassunge had higher pre-ART LTFU rates, especially in the first few months after being enrolled in care.

As of June 2012, 376 (4.1 %) of those LTFU had re-engaged in care at the same health facility.

Qualitative Analysis

A total of twenty pre-ART patients aged 18–41 years were interviewed in one district, namely Maganja da Costa. The sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of participants are provided in Table 3. Seven patients refused to participate. Reasons for not participating include: too sick [2], concern that family would discover their HIV status [2], discomfort in participating in a study [1], concern about participating coupled with not seeing a benefit to participating [1], and leaving to attend a funeral ceremony outside of the district [1]. The bulk of those interviewed (16, 80 %) were women, reflecting the patient population characteristics, which has a higher proportion of female patients, which in turn reflects both higher HIV prevalence among women in the province, as well as their higher uptake of healthcare services. Timing of home visits during daytime hours may also affect the number of men found at home.

We asked participants their reasons for not returning to the clinic. Three participants did not respond to this question. The most commonly cited reasons were related to logistical factors (geographic distance, lack of transport and competing priorities) (6/17), followed by fear of repercussions from spouses (all female participants) (3/17), and perceived poor quality of care at the facility (4/17). Other reasons included advice from traditional healers (1/17), denial of HIV status or continued illness (2/17), and shame (1/17).

The reason I did not come back was because I had been poorly attended [at the facility], and also because when my husband finds out about my status, I run the risk of divorce—40-year-old female

The reasons are distance, and lack of means, because when I go to the hospital I stay the whole day and return at night without eating anything.—27-year-old female

We asked participants what would encourage them to return to the facility. Among the 12 who responded, a majority [5] noted that improved services, including better counseling and support, would encourage them to return to the facility for healthcare. Three stated they would return if they could receive help caring for their dependents at home, or transportation assistance. One woman stated that her husband’s awareness of her status would encourage her to return. Three provided nonspecific responses.

When probed further about what would encourage them to remain in care, many (5/11) repeated their wish to remain in good health. A few responded that they would remain in care if placed on antiretroviral treatment. Some expressed their desire for improved services at the health facility.

Participants were asked why it might be important for them to return to clinic; 6 chose not to respond. Of the 14 who responded, 9 stated it was important for them to return to the health facility to remain healthy. Some cited reasons for wishing to maintain their health, such as caring for their children or in order to work. When asked about possible consequences of not returning to the clinic, the majority (15 of the 16 who responded) felt it would lead to worse health status and/or death. Among those responding to specific probes on the consequences of not returning to the health facility on livelihood, all felt that it would be adversely affected, with a few specifically stating that it would be difficult for them to work.

If I do not return again to the health post, my life will end automatically.—24-year-old female

We explored disclosure among participants, asking to whom they had disclosed their HIV status and for what reasons. Only four of 20 had disclosed their HIV status to their household’s main income provider, providing trust and duty as reasons for doing so. Only two of those who had not yet disclosed their HIV status to their primary income provider gave reasons, stating they were afraid of their husbands and of the consequences of disclosing. Only nine of the twenty respondents, including all four men, had shared their status with someone else in their family; main reasons included trusting the individual who they told, precaution in case of need of unspecified support in the future, and a sense of duty/obligation. Male participants told members of their families out of trust and a sense of duty, while many of the female participants confided in another family member from whom they could draw support, often not their spouse.

I decided to tell her so that she could give me support, and help me with difficult issues—28 year old female

Of those who had not told others in their family (all women), most stated that it was out of fear, mostly of a general “other” person finding out, along with shame of their HIV status. Lack of trust in others’ ability to maintain privacy was also mentioned.

A subset of respondents speculated on their families’ reactions were they to find out, the majority expressing concerns that family members or spouses would isolate them. A smaller number felt that while the information would sadden family members, they would ultimately take care of them.

My family’s reaction would be to take care of my HIV status because this happens in other families.—27-year-old female

We also asked whether community members were aware of their status. Only one participant reported having disclosed his HIV status to the community, and stated there had been no negative repercussions. The overwhelming reason for keeping silent among the rest was fear of a negative response, of what others would say, and of being isolated. Some also specifically mentioned that they would feel ashamed. Only one participant believed her community would not speak poorly of her, because of community HIV education campaigns.

The reasons for not telling are because I was afraid. I know that when I was told that I have HIV that it is an illness that gives a lot of fear and shame when people find out you are seropositive.—30-year-old male

To better understand the context surrounding disclosure, participants were asked about community attitudes towards those with HIV. Of those who responded, half felt their communities reject HIV-infected individuals, out of fear of infecting others, and perception of HIV-infected individuals to be promiscuous women or prostitutes. Other common perceptions were that HIV-infected people would die soon or need to be hospitalized. Only two believed that the community had a positive outlook towards those with HIV, as individuals who deserve respect and to be treated as anyone else, mentioning education and activism as reasons why individuals with HIV are not rejected.

I didn’t tell anyone because I was afraid to tell someone who would go and reveal the secret of my status.—27-year-old female.

Discussion

Quantitative results from this highly populated, predominantly rural and impoverished region in Mozambique are consistent with published studies showing that retaining persons in care within the critical pre-ART window remains a significant challenge, with more than half of those enrolled in pre-ART care being typically LTFU by the 1 year mark [26]. Identifying reasons for LTFU is important in planning programmatic approaches to bolster retention. Analyzing sociodemographic characteristics, one sees that being younger (<30 years of age) is a significant risk factor, mirroring the well-documented trend among those who have initiated ART [27]. Another clear risk factor is being male; as in this study, there was a 32 % increased risk of being LTFU among males, which has also been supported by other studies conducted within the region [14]. There is evidence to suggest that males have poorer outcomes in terms of both adherence and mortality, even after initiating potentially life-saving ART [18, 28, 29]. This occurs in the context of programmatic emphasis on identifying and treating HIV infected women of reproductive age, who represent a larger proportion of those infected. These differences in pre-ART LTFU rates warrant more in-depth contextual analysis. Adolescents aged 15–17 represent <2 % of our pre-ART population and were excluded from our study; yet, they are known to have particular challenges around retention that also warrant future, separate study. With strategies such as mothers’ support groups and individual counseling being the mainstay of counseling strategies for this population in this setting, there is room for tailoring counseling and service delivery strategies to sustain engagement of males in the healthcare available. Unfortunately, our qualitative results are largely from women, as they were the ones available and willing to participate in the qualitative interviews. More information is needed to understand why men are LTFU at higher rates and what might encourage them to stay in care.

The impact of the definition of pre-ART LTFU is prominent in Fig. 1 where large increases in the percentage of pre-ART LTFU occur at 3 and 6 months. Studies in the literature have shown that definitions of LTFU may impact estimates of retention and mortality [30]. Differences by district merit further analysis, as they may reflect differences due to the number and size of the health facilities in the districts, patient volume, and patient-to-staff ratios at each site, the availability of onsite CD4+ count testing, the length of time the HIV care and treatment program has been functioning, distances to health facilities, the availability of transportation, and other social and economic factors. Clearly, more in-depth quantitative as well as qualitative studies are needed to better understand these preliminary differences between districts.

While little has been studied among pre-ART populations, there is evidence that those LTFU during ART generally fall into two categories: those too ill to return who succumb to their illness, and those who decide not to return to the clinic because they feel well and are relatively healthy [31]. We are limited in our ability to clinically describe the population by the very fact that they did not return to the clinic. However, when a CD4+ count was obtained, having a lower initial CD4+ count was associated with an increased likelihood of becoming LTFU, suggesting that perhaps the clinical consequences of more advanced immunosuppression, such as weakness and/or fatigue due to HIV associated wasting, comorbid disease in the form of other opportunistic infections, and/or or death, kept them from returning to clinic. This raised the possibility that there may be two distinct populations of pre-ART individuals not returning for care: those who are relatively healthy and young, and those having such advanced immunosuppression (i.e. having CD4+ count values <50–100 cells/mm3) that they are unable to return to clinic. Additional larger studies in the region evaluating more in-depth the clinical, laboratory, and additional sociodemographic factors of those immediately LTFU are urgently needed.

It is important to keep both groups of patients enrolled and engaged in care and placed on ART as soon as eligible (CD4 count <250 cells/mm3, or WHO clinical stage III or IV), as patients in this setting often suffer substantial morbidity and mortality during the first year following ART initiation [32]. There is also mounting evidence that beginning ART in those having higher baseline CD4+ counts results not only in better survival, but also in better adherence [9, 33]. Likewise, relatively “healthy” individuals having higher initial CD4+ counts are likely to be more sexually active, and as such represent a targeted public health risk population that requires extensive targeted behavior communication campaigns to prevent incident HIV infections [34].

Socio-economic status also was an important predictor of LTFU. Those with less formal education and who did not have electricity in their home, both markers of lower socio-economic status, were more likely to be LTFU. Having less years of formal education however, does not necessarily mean less understanding of the importance of staying in care; the majority of those interviewed mentioned the importance of going to clinic and the consequences to their health were they not to return. Additionally, adults in rural provinces within SSA such as Zambézia typically have the heightened responsibility of caring and providing for younger children, a time constraint suggested by the qualitative interviews as affecting appointment adherence. This study is supported by other studies of pre-ART populations in this region, that found lower education status and being unmarried correlated with an increased risk of becoming LTFU [35]. Evidence that participation in groups for logistical and psychosocial support decreases the risk of becoming LTFU in the ART population may be relevant for piloting such groups in the pre-ART population [36, 37].

The study’s qualitative results raised the possibility that perceived quality of health care provided at these facilities might affect LTFU, as some participants disclosed they would return were they better treated or counseled at the facilities. Perceived poor quality of care at these facilities has previously been found to be a deterrent from participating in care [38]. More extensive qualitative work is needed to assess whether varying rates of LTFU by district could reflect differences in the quality of care provided. LTFU was highest in the district having one of the largest and highest volume health HIV services.

In light of an array of competing responsibilities with immediate tangible returns, such as working in the fields or taking care of one’s family, it is possible that some may choose to forego a clinic visit which is time consuming and for which they see no immediate benefit. As pre-ART patients are not receiving ART in exchange for time spent in coming to the clinic, the qualitative data suggest that they might prefer to not miss a day of work. The qualitative results also suggest that counseling or at least some tangible encouragement from the counselors at the clinic may encourage patients to return.

While the quantitative analysis shows that men are more likely to become LTFU during pre-ART than women, the qualitative analysis highlights several important issues of disclosure among women in this population. A majority of female participants in the qualitative interviews who were not main income providers of their household stated they were unlikely to have disclosed their status to the head of household (6/10). Eleven of 16 women did not disclose their status to anyone in their family because of fear and shame. They also feared isolation and general negative reactions from their communities. Thus, it is possible that some may avoid the clinic and discontinue care because they do not wish their family or communities to become suspicious about their health. This may help explain why referral from PMTCT represents an increased risk of LTFU in the quantitative results, as nondisclosure to spouses and others might affect clinic attendance. More attention on male engagement in the healthcare system could improve acceptability of clinic visits among female patients and improve retention among male patients in the process.

Limitations

This study did suffer from several limitations. First, because so many patients were LTFU very early on, there is a limited amount of clinical data available for analysis of this group. Quality of the data in the electronic database is good with routine audits and daily, onsite electronic data entry. Missing data are common; data quality audits point to missing data in the patient record as the greatest contributor to poor quality data in the electronic database. Moreover, much of the data from the clinical records from that first visit is missing, a reflection on the quality of care provided and of the poor quality of the health information system—missing data could reflect either lack of proper documentation of what was done, or that the service was inadequate. Missing data may include missing information on whether the patient transferred out of the facility. At the time of this study CD4+ count machines were not routinely available in many facilities and samples had to be drawn and transported centrally to laboratories having such capacity. The introduction of point-of-care (POC) CD4+ count devices by the Mozambican Ministry of Health (MISAU) in Zambézia in March/April 2013 may reduce LTFU before initial CD4+ count assessments have been completed. A second limitation in the quantitative portion is that there is no way of knowing from the data extracted from the clinical charts whether those patients counted as LTFU are indeed lost and not simply undocumented transfers, again a reflection of the quality of the health information system.

Third, while qualitative interview across all districts would have been ideal, interviews were only completed in one district, albeit a representative district as the quantitative analysis showed. The patients interviewed in Maganja da Costa were similar in clinical and demographic characteristics to other LTFU patients in the other districts. Also, we were only able to interview a very small sample of participants because of resource restrictions. These interviews were completed by community volunteers who, while trained, were not professional research staff. Concerns around disclosure to community members may also have created bias in responses by participants to the community volunteers, including nonresponse bias. Finally, although men are at higher risk of pre-ART LTFU as our quantitative analysis shows, our interviews were done mostly with women. Women still represent a disproportionate amount of those in care (and LTFU) in this pre-ART population. Still, subsequent qualitative research should target multiple districts and attempt to enroll significantly higher numbers of participants in order to obtain a representative sample, perhaps purposively sampling more men.

Conclusions

Pre-ART loss to follow-up is a significant problem in this impoverished and predominantly rural province in Mozambique. While efforts continue to be made to improve patient adherence to ART, it is imperative that resources are committed to retaining patients not yet assessed for eligibility or not ART-eligible. Specifically, men, younger persons, and the less educated appear to be at heightened risk for loss to follow up. Among the 20 pre-ART patients participating in qualitative interviews, the vast majority (15/16) seem to understand the importance of remaining in care, while logistics, stigma, concerns surrounding disclosure and perceived quality of care appear to be important factors influencing an individual’s decision to present for care. Further examination of this population is warranted given the small sample size of this qualitative study.

References

World Health Organization. Antiretroviral therapy for HIV infection in adults and adolescents. Recommendations for a public health approach. Geneva, Switzerland: Author;2010.

World Health Organization. Consolidated guidelines on the use of antiretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV infection. Recommendations for a public health approach. Geneva, Switzerland: Author;2013.

Wester CWBH, Koeth J, Moffat C, Vermund S, Essex M, Marlink RG. Combination antiretroviral therapy in sub-Saharan Africa: lessons from Botswana and future challenges. HIV Ther. 2009;3(5):501–26.

World Health Organization Organization. HIV treatment: global update on HIV treatment 2013: results, impact and opportunities. WHO report in partnership with UNICEF and UNAIDS. 2013. (29 Apr 2014). http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/unaidspublication/2013/20130630_treatment_report_en.pdf.

Rosen S, Fox MP, Gill CJ. Patient retention in antiretroviral therapy programs in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. PLoS Med. 2007;4(10):e298.

Mugglin C, Estill J, Wandeler G, Bender N, Egger M, Gsponer T, et al. Loss to programme between HIV diagnosis and initiation of antiretroviral therapy in sub-Saharan Africa: systematic review and meta-analysis. Trop Med Int Health. 2012;17(12):1509–20.

Rosen S, Fox MP. Retention in HIV care between testing and treatment in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. PLoS Med. 2011;8(7):e1001056.

Giordano TP, Gifford AL, White AC Jr, Suarez-Almazor ME, Rabeneck L, Hartman C, et al. Retention in care: a challenge to survival with HIV infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(11):1493–9.

Clouse K, Pettifor A, Maskew M, Bassett J, Van Rie A, Gay C, et al. Initiating antiretroviral therapy when presenting with higher CD4 cell counts results in reduced loss to follow-up in a resource-limited setting. Aids. 2013;27(4):645–50.

Severe P, Juste MA, Ambroise A, Eliacin L, Marchand C, Apollon S, et al. Early versus standard antiretroviral therapy for HIV-infected adults in Haiti. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(3):257–65.

Lessells RJ, Mutevedzi PC, Cooke GS, Newell ML. Retention in HIV care for individuals not yet eligible for antiretroviral therapy: rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;56(3):e79–86.

Grinsztejn B, Hosseinipour MC, Ribaudo HJ, Swindells S, Eron J, Chen YQ, et al. Effects of early versus delayed initiation of antiretroviral treatment on clinical outcomes of HIV-1 infection: results from the phase 3 HPTN 052 randomised controlled trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14(4):281–90.

Pati R, Lahuerta M, Elul B, Okamura M, Alvim MF, Schackman B, et al. Factors associated with loss to clinic among HIV patients not yet known to be eligible for antiretroviral therapy (ART) in Mozambique. J Int AIDS Soc. 2013;16:18490.

Geng EH, Bwana MB, Muyindike W, Glidden DV, Bangsberg DR, Neilands TB, et al. Failure to initiate antiretroviral therapy, loss to follow-up and mortality among HIV-infected patients during the pre-ART period in Uganda. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;63(2):e64–71.

Hoffmann CJ, Lewis JJ, Dowdy DW, Fielding KL, Grant AD, Martinson NA, et al. Mortality associated with delays between clinic entry and ART initiation in resource-limited settings: results of a transition-state model. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;63(1):105–11.

Hull MW, Wu Z, Montaner JS. Optimizing the engagement of care cascade: a critical step to maximize the impact of HIV treatment as prevention. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2012;7(6):579–86.

Endicott P, Metspalu M, Stringer C, Macaulay V, Cooper A, Sanchez JJ. Multiplexed SNP typing of ancient DNA clarifies the origin of Andaman mtDNA haplogroups amongst South Asian tribal populations. PLoS One. 2006;1:e81.

Kanters S, Nansubuga M, Mwehire D, Odiit M, Kasirye M, Musoke W, et al. Increased mortality among HIV-positive men on antiretroviral therapy: survival differences between sexes explained by late initiation in Uganda. HIV/AIDS (Auckl, NZ). 2013;5:111–9.

Haines T, Stringer B. Physical exertion at work during pregnancy did not increase risk of preterm delivery or fetal growth restriction. Evid Based Med. 2006;11(5):156.

Kilmarx PH, Mutasa-Apollo T. Patching a leaky pipe: the cascade of HIV care. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2013;8(1):59–64.

Moon TD, Burlison JR, Sidat M, et al. Lessons learned while implementing an HIV/AIDS care and treatment program in rural Mozambique. Retrovirol Res Treat. 2010;(3):1–14.

Fe H. Regression modeling strategies: with applications to linear models, logistic regression, and survival analysis. New York: Springer; 2001.

R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. 2013. http://www.R-project.org/.

Instituto Nacional de Estatística (INE), I.M., Inquérito Nacional de Prevalência, Riscos Comportamentais e Informação sobre o HIV e SIDA (INSIDA) em Moçambique 2009. In 2010 Calverton, Maryland, EUA: INS, INE, e ICF Macro.

Miller CM, Ketlhapile M, Rybasack-Smith H, Rosen S. Why are antiretroviral treatment patients lost to follow-up? A qualitative study from South Africa. Trop Med Int Health. 2010;15(Suppl. 1):48–54.

Micek MA, Gimbel-Sherr K, Baptista AJ, Matediana E, Montoya P, Pfeiffer J, et al. Loss to follow-up of adults in public HIV care systems in central Mozambique: identifying obstacles to treatment. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;52(3):397–405.

Evans D, Menezes C, Mahomed K, Macdonald P, Untiedt S, Levin L, et al. Treatment outcomes of HIV-infected adolescents attending public-sector HIV clinics across Gauteng and Mpumalanga, South Africa. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 2013;29(6):892–900.

Maskew M, Brennan AT, Westreich D, McNamara L, MacPhail AP, Fox MP. Gender differences in mortality and CD4 count response among virally suppressed HIV-positive patients. J Women’ Health. 2013;22(2):113–20.

Cornell M, Schomaker M, Garone DB, Giddy J, Hoffmann CJ, Lessells R, et al. Gender differences in survival among adult patients starting antiretroviral therapy in South Africa: a multicentre cohort study. PLoS Med. 2012;9(9):e1001304.

Shepherd BE, Blevins M, Vaz LM, Moon TD, Kipp AM, Jose E, et al. Impact of definitions of loss to follow-up on estimates of retention, disease progression, and mortality: application to an HIV program in Mozambique. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;178(5):819–28.

Charurat M, Oyegunle M, Benjamin R, Habib A, Eze E, Ele P, et al. Patient retention and adherence to antiretrovirals in a large antiretroviral therapy program in Nigeria: a longitudinal analysis for risk factors. PLoS One. 2010;5(5):e10584.

Gupta A, Nadkarni G, Yang WT, Chandrasekhar A, Gupte N, Bisson GP, et al. Early mortality in adults initiating antiretroviral therapy (ART) in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC): a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2011;6(12):e28691.

Peltzer K, Ramlagan S, Khan MS, Gaede B. The social and clinical characteristics of patients on antiretroviral therapy who are ‘lost to follow-up’ in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa: a prospective study. SAHARA J Soc Asp HIV/AIDS Res Alliance. 2011;8(4):179–86.

McGrath N, Richter L, Newell ML. Sexual risk after HIV diagnosis: a comparison of pre-ART individuals with CD4>500 cells/microl and ART-eligible individuals in a HIV treatment and care programme in rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. J Int AIDS Soc. 2013;16:18048.

Hassan AS, Fielding KL, Thuo NM, Nabwera HM, Sanders EJ, Berkley JA. Early loss to follow-up of recently diagnosed HIV-infected adults from routine pre-ART care in a rural district hospital in Kenya: a cohort study. Trop Med Int Health. 2012;17(1):82–93.

Fatti G, Meintjes G, Shea J, Eley B, Grimwood A. Improved survival and antiretroviral treatment outcomes in adults receiving community-based adherence support: 5-year results from a multicentre cohort study in South Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;61(4):e50–8.

Lamb MR, El-Sadr WM, Geng E, Nash D. Association of adherence support and outreach services with total attrition, loss to follow-up, and death among ART patients in sub-Saharan Africa. PLoS One. 2012;7(6):e38443.

Groh K, Audet CM, Baptista A, Sidat M, Vergara A, Vermund SH, et al. Barriers to antiretroviral therapy adherence in rural Mozambique. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:650.

Acknowledgments

We thank Marcia Souza, Robert Burny, Deidra Parrish, Cameron Ingram and the volunteer community AIDS activists in Maganja da Costa for their assistance. We also thank Candace Miller and Sydney Rosen for sharing the data collection instruments from their study.

Conflict of interest

This research has been supported by the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) through the US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention under the terms of Cooperative Agreement #U2GPS000631. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the CDC.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

da Silva, M., Blevins, M., Wester, C.W. et al. Patient Loss to Follow-Up Before Antiretroviral Therapy Initiation in Rural Mozambique. AIDS Behav 19, 666–678 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-014-0874-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-014-0874-0