Abstract

Diffusion of innovation (DOI) is widely cited in the HIV behavior change literature; however there is a dearth of research on the application of DOI in interventions for sex workers. Following a randomized-controlled trial of HIV risk reduction among female entertainment workers (FEWs) in Shanghai, China, we used qualitative approaches to delineate potential interpersonal communication networks and contributing factors that promote diffusion of information in entertainment venues. Results showed that top-down communication networks from the venue owners to the FEWs were efficient for diffusion of information. Mammies/madams, who act as intermediaries between FEWs and clients form an essential part of FEWs’ social networks but do not function as information disseminators due to a conflict of interest between safer sex and maximizing profits. Diffusion of information in large venues tended to rely more on aspects of the physical environment to create intimacy and on pressure from managers to stimulate communication. In small venues, communication and conversations occurred more spontaneously among FEWs. Information about safer sex appeared to be more easily disseminated when the message and the approach used to convey information could be tailored to people working at different levels in the venues. Results suggest that safer sex messages should be provided consistently following an intervention to further promote intervention diffusion, and health-related employer liability systems in entertainment venues should be established, in which employers are responsible for the health of their employees. Our study suggests that existing personal networks can be used to disseminate information in entertainment venues and one should be mindful about the context-specific interactions between FEWs and others in their social networks to better achieve diffusion of interventions.

Resumen

La difusión de innovaciones es ampliamente citada en la literatura sobre el cambio de comportamiento. No obstante, la aplicación de esta teoría en intervenciones dirigidas a trabajadores sexuales es limitada. Luego de un ensayo aleatorizado controlado para la reducción del VIH en trabajadoras del entretenimiento (TE) en Shanghai, China, utilizamos enfoques cualitativos para delinear potenciales redes interpersonales de comunicación y los factores que contribuyen a promover la difusión de información en locales de entretenimiento. Los resultados mostraron que las redes de comunicación de arriba hacia abajo de los propietarios de los locales a las TE fueron eficientes en la difusión de información. Madams, quiénes actúan como intermediarias entre las TE y los clientes, constituyen una parte esencial de las redes sociales de las TE, pero no funcionan difundiendo información debido a un conflicto de interés entre el sexo seguro y la maximización de las ganancias. La difusión de información en locales grandes tendió a basarse más en el ambiente físico para crear intimidad y en la presión de los gerentes para propiciar la comunicación. En locales pequeños, la comunicación y las conversaciones ocurrieron de manera mas espontánea entre las TE. La información acerca del sexo seguro fue más fácil de difundirse cuando el mensaje y el enfoque usado para transmitir la información podía adecuarse a las personas que trabajan en diferentes niveles en los locales. Los resultados sugieren que mensajes sobre el sexo seguro deben brindarse de manera consistente luego de una intervención para seguir promoviendo la difusión de la intervención, y deben establecerse los sistemas de responsabilidad en cuanto a salud se refiere de los empleadores en locales de entretenimiento, en los cuales los empleadores son responsables de la salud de sus empleados. Nuestro estudio sugiere que las redes personales existentes pueden ser usadas para difundir información en locales de entretenimiento y uno debe de ser consciente acerca de las interacciones entre las TE y los otros en sus redes en contextos sociales específicos para lograr una mejor difusión de las intervenciones.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

As in many developing countries, the commercial sex industry in China is thriving along with its economic development [1]. Large-scale urbanization has resulted in massive rural-to-urban migration, which not only contributes to an escalating demand for commercial sex in urban areas but also provides an enduring supply of young sex workers [2]. An estimated of 4–10 million Chinese women were engaged in commercial sex at the end of 2004 [3]. With the expansion of the commercial sex industry, a rapid increase in sexually transmitted infections (STIs) among sex workers has occurred [4]. Recent reports among female sex workers show that STI prevalence among this population in China ranged from 13 to 57 % and HIV prevalence to have risen from 1.1 % in 2004 to 2.1 % in 2005 with the prevalence at HIV “hotspots” to be between 5 and 10 % [5, 6]. Meanwhile, China has also witnessed a concurrent increase in the proportion of HIV positive individuals infected through heterosexual transmission. By August 2010, it was estimated that 53.8 % of an accumulated 740,000 (560,000–920,000) HIV positive individuals in China were infected through heterosexual transmission, a 10 % increase since the end of 2009 [7]. These alarming trends have highlighted an urgent need for HIV risk reduction interventions among populations at high risk of HIV infection through sexual transmission in China. Among many available public health strategies to curb HIV transmission, behavioral interventions targeting female sex workers are considered cost-effective [8]. However, current demonstrated successful prevention strategies such as peer-education and counseling have been struggling with the issue of sustainability.

Diffusion of innovation is a theoretical approach that may enhance sustainability of interventions [9]. It refers to the ability of an intervention to affect behaviors of people who are not part of the intervention but are within the same community of people who receive the intervention [10]. Interventions that promote diffusion of innovation often target social networks that encompass specific structures or individuals who are particularly influential (e.g. ‘opinion leaders’) within the network [9, 11, 12]. HIV-related behavioral interventions based on diffusion of innovation theories have yielded successful results in some cases but the overall effects across studies are mixed [13]. A recent five-country group-randomized HIV intervention trial targeting at opinion leaders in communities also failed to achieve better results in the diffusion sites as compared to the other sites where no social diffusion approach was adopted [14]. The lack of success in some earlier efforts, however, further prompted calls for additional research with this widely appreciated approach [15]. Aral has suggested that behavioral change may be easier to maintain if an intervention is designed and implemented in line with structural characteristics of the existing network [16]. Valente et al. [17] has borrowed the concept of audience segmentation from marketing communication, where audiences are partitioned into distinct groups and messages are tailored specifically to each group.

Although the utility of diffusion of innovation theory has been widely recognized and efforts toward its further development in behavioral interventions keep ongoing, there is surprisingly little reference to this approach in the vast literature of HIV/AIDS prevention from the developing world [18]. Moreover, almost no such research has specifically been conducted among female entertainment workers (FEWs) to guide design of relevant interventions. The current study, therefore, will respond to the call for further research that can inform the design of diffusion-promoted HIV-risk reduction interventions among sex workers. This study is a qualitative follow-up to a randomized controlled trial of an HIV behavioral intervention among young female sex workers in entertainment venues in Shanghai, China. The intervention sessions included basic HIV/STD information, motivation enhancing and behavioral skills training. The control sites received reduced sessions with only basic HIV/STD information. The intervention was delivered both to FEWs and their gatekeepers, defined as persons who manage sex workers (e.g., establishment owners, managers, or mammies), and have a reciprocal financial relationship with FEWs [19]. Owners or managers usually have the top executive authority in a commercial sex venue, while mammies work as team leaders for sex workers under the supervision of the venue owners or managers. Gatekeepers were included in the intervention for their influence on FEWs.

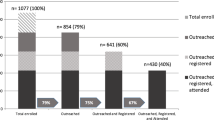

Diffusion of an intervention can be assessed by recruiting participants’ network members and monitoring their self-reported risk behaviors [10]. In a previous quantitative evaluation of the program, new participants recruited at the intervention sites during the post-intervention surveys demonstrated a similar pattern of decline in risk behaviors as the participants receiving the intervention [20], a phenomenon not occurring among new participants recruited during follow-up at the control sites. We therefore speculated that such parallel and consistent reductions in risk behaviors among the newly recruited participants at the intervention sites could be a result of information diffused through the intervention, by means of the social networks of the FEWs who had received the intervention. Moreover, the illegality of sex work is likely to limit FEWs’ social networking outside the venues where they work. And it is thus reasonable to assume that a dense and isolated network inside the intervened venues is to be credited for the sustained behavior change [10].

Based on the above-mentioned assumptions, we designed the current study to: (1) investigate the dynamics of diffusion of information through social networks in the context of commercial sex, and (2) suggest characteristics of intervention design necessary to ensure optimal diffusion of information among FEWs working at entertainment venues. Because high-end or large entertainment venues (e.g., nightclubs, karaoke) tended to have different structural characteristics as compared to low-tier or small venues (e.g., massage parlors, beauty salons), the study was designed to distinguish between them in order to make our results more relevant to each of these types of work settings.

Methods

Participants and Data Collection

The current study focuses on FEWs, the main target of our intervention, and hence does not include non-entertainment sex workers. Details of the participants in the HIV risk reduction intervention trial can be found elsewhere (see [20] for details). After the 12-month post-intervention assessment, FEWs from the intervention sites were invited by intervention study staff, intervention outreach workers, or survey conductors, to participate in in-depth interviews (IDI).

Key informant sampling, a method often used in qualitative research to identify members of a community who are knowledgeable about relevant topics, was used to select FEWs [21]. For FEWs who received the intervention, we expected our key informants to have a higher than average participation rate in intervention sessions, and/or have at least 2–3 years of work experience in the commercial sex industry. Regarding new FEWs, we recruited those who had heard of the intervention and/or HIV-related information from their colleagues. Intervention staff members with frequent interactions with FEWs were also requested to recommend potential participants. A total of 21 FEWs (16 from large venues and 5 from small venues) were interviewed. Interviews were conducted in private spaces with one interviewer, usually an intervention staff member who had established good rapport with the respondent.

A general interview guide was prepared in advance for both intervened and new FEWs. A majority of questions designed for FEWs who participated in the intervention focused on the circumstances and locations where they would initiate or engage in communication of health-related information in the venues. For new FEWs, we were interested in knowing from what source they received information regarding our intervention, especially if it involved communication with participating FEWs. Interviewers were also encouraged to pursue lines of questioning based on participant responses and the interviewer’s knowledge of intervention procedures. The IDIs were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim with participant permission. Due to the sensitivity of the topic and the legal status of FEWs, permission to audiotape was rarely given, in which case extensive notes were taken by the interviewers. Each interview lasted 1–2 h and each respondent received stipend of 200 Yuan (approximately $30) for their participation. In addition, we also interviewed two intervention outreach workers and two survey interviewers, who had worked in the field extensively and had frequent interactions with FEWs and gatekeepers. They were included because of their experience with entertainment venues and ability to generate rich insights for our study. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at Old Dominion University in the USA and at Shanghai Academy of Social Science in China in 2006.

Content analysis was conducted concurrently with data collection to allow revision of the interview guide. The analysis focused on generating themes related to communication of intervention material and potential social networks within the venue that may facilitate such communication. Transcripts were first hand-coded by the investigator and cross-coding was performed by two research assistants. Discrepancies between codes were resolved through extensive discussions. The analysis was conducted using ATLAS.ti version 6.2 [22]. Saturation was reached among respondents from large venues as no new themes were generated during final interviews. However, in small venues, it was not possible to determine if saturation was reached due to small sample size.

Results

Table 1 shows the composition of the FEWs interviewed by venue type. A total of 25 people were interviewed including: 21 FEWs from the intervention sites, two intervention outreach workers and two survey interviewers who had experience in both control and intervention sites. The FEWs participating in the study were predominantly migrants with a mean age at 26, ranging from 18 to 36. The majority were never married and those who had ever married were almost exclusively from small venues. FEWs from small venues were older than those from large venues on average and were generally less educated. Around 43 % of our participants had worked in the sex industry for at least 3–4 years and some had worked as long as 8 years.

A summary of key networks identified in entertainment venues are presented in Table 2 accompanied by empirical evaluation of the ability of each network to diffuse information from the intervention.

Top-Down Networks Formed by Venue Owners/Managers to FEWs

Owners and managers of each venue actually received the intervention prior to the FEWs within those venues and thus become a key conduit of intervention information. In most of the big intervention venues, a weekly meeting required for FEWs would be held by the lead manager or the venue owner, which generated opportunities for the boss to diffuse intervention-related information to his/her staff:

“We meet the boss every Monday and each FEW attends the meeting. Our boss told us in the meeting that the ‘classes’ (intervention sessions) are worth attending. He is really supportive of us taking the classes. After the classes, he often reminds us that health should be our priority and we can make more money if we are healthy. He even jokes that the intervention saves us money to buy condoms and reminds us that no one else outside might be this considerate of us.” (FEW013, age 27, migrant, single, primary school education, 4 years in the industry)

Because of the illegality of commercial sex and the concerns for privacy and legal consequences of revealing their identities, FEWs tended to be suspicious and hostile to public AIDS prevention programs. But the acceptance of the owner instilled trust in the intervention program and raised the acceptability of intervention content among FEWs. Noticeably not all of the bosses had a good reputation among FEWs. One girl from a large venue mentioned lack of respect for her boss due to the fact that he charged the FEWs too many taxes and other fees. Yet in most of the venues, the role of “the boss” confers a certain respect from the staff and enhanced the impact of the intervention among FEWs in the venues.

The communication between managers and FEWs mostly occurred in large venues where a more developed management structure exists. In the study we found that the owners of most small venues rarely came to the venues. The fact that profits in small venues came almost exclusively from sex trade than from alcohol, as in most large venues, also made owners of small venues negative about promoting safe-sex, an activity which they believed might jeopardize the profitability of their business.

Communication Network Between Mammies (Madams) and FEWs

The same as the boss-to-FEWs communication network, the network formed by mammies and FEWs was also mainly featured in large venues. Mammies (madams) are the ones that usually have the most frequent contact with FEWs and most of them were former experienced FEWs themselves. They function as agents for FEWs and exert direct control over them. Every night mammies reserve several guest rooms subleased from the venue owner and earn money by collecting a certain percentage (10–20 %) of the commission fee from each client, upon introducing their FEWs to clients.

Given the direct leadership of mammies and the fact that they also received the intervention along with the venue owners, it might be expected that the intervention content would be communicated via mammies to FEWs. Of note, however, is that intervention information diffused through this network is not common in most venues:

“It is good have you have come and talk to us. Mammy never talks about these things with us. Perhaps she also doesn’t know. But she does not care about FEWs’ health and all she cares about is that you go and get clients.” (FEW013, age 25, migrant, single, primary school education, 4 years in the industry)

Outreach workers, who had direct contact with mammies, had the clearest understanding of the lack of support from mammies for the intervention and of the likelihood for them to disseminate intervention information to FEWs.

“Mammies barely showed up to intervention sessions. Even for those who came, they didn’t really talk to the girls (FEWs) about it (the intervention sessions) afterwards.” (FCLT01, age 55, retired physician)

Both outreach workers who were interviewed expressed concern that mammies did not generally disseminate intervention-related information to FEWs and complained that mammies usually held a negative attitude towards the intervention activities.

Communication Networks Formed by FEWs Working in the Same Venue

Communication Networks in Large Venues

One of the most common locations for communication of intervention material was in the waiting room. Due to the large number of FEWs employed, large venues usually provide FEWs with a relatively spacious room for resting and changing when they were waiting for clients. This relatively private space creates an environment that is conducive for diffusion of information. Several participants mentioned that conversations tended to start easily and naturally when they were in the waiting room:

“In the waiting room, new FEWs will stay with old FEWs. We don’t feel as embarrassed to discuss these things (sex and condoms) in the venue compared to when we are outside.” (FEW008, age 23, migrant, single, primary school education, 4 years in the industry)

In addition to the waiting room, the guest room also provides an opportunity for diffusion of information. In large venues such as karaoke and nightclubs, mammies assign several FEWs to the same room every night and require experienced FEWs to act as mentors for new FEWs. In this case, requests from mammies to encourage mutual support among FEWs promoted a sense of responsibility for experienced FEWs to talk to and teach the newcomers:

“Sometimes mammies would ask us to show pity for new girls who were in the same room with us and teach them things they didn’t understand. In this case, we would tell them a lot of things and teach them a lot.”(FEW009, age 28, migrant, single, middle school education, 8 years in the industry)

The program did not designate specific people to take responsibility for being peer-educators but intervention material still crept into their daily discussions under certain circumstances. FEWs who discussed intervention-related material usually admitted that, for various reasons, they never intentionally tried to teach these things to co-workers, but “chatting off and on we might naturally touch upon those topics.”

Communication Networks in Small Venues

In contrast to large venues where dozens or even hundreds of FEWs work together, FEWs in small venues know each other by name and have direct communication with all co-workers. Also, the administrative structure is relatively simpler with only two levels: the boss and FEWs. The small number of staff and a high level of closeness among co-workers facilitated the diffusion of information among FEWs and even led to a deep level of engagement:

“We talked about condoms, boyfriends and things like that, such as ‘condoms can protect us’ and ‘we may be infected by HIV if we don’t use condoms.’ Sometimes there would be arguments among us. Some girls said they never used them and others said that we must use them. And they would argue.” (FEW010, age 18, migrant, single, middle school education, 1.5 years in the industry)

Unlike in large venues where mammies may request that experienced FEWs provide guidance to newcomers, the lack of mammies or intermediate agents in small venues tended to encourage more direct interaction and self-initiated trade of information among FEWs themselves. As mentioned by a FEW: “They (the more experienced FEWs) will tell us how to use condoms properly and other things if we buy them some snacks.” Such self-initiated trade of information could provide experienced FEWs with a motivation to share their knowledge with others and “once you (new FEWs) do that, she (an experienced FEW) will always tell you.”

The small number of FEWs working in one venue also makes it easier for FEWs to reach an agreement regarding practicing safer sex and to identify those who do not agree and, thus, provide more intense peer supervision and peer pressure to help boost condom use among new FEWs.

“After your people came last year, basically we encouraged each other to wear condoms, [to decide] no matter what, if you (FEWs) don’t use condoms, then don’t accept clients. Otherwise clients may all choose you and then what are other girls expected to do? There was one girl who did not use condoms, so everyone dislikes her.” (FEW017, age 29, migrant, single, primary school education, 8 years in the industry)

Communication Networks Among Female Entertainment Workers from the same Hometown and Close Friends

FEWs working in Shanghai are from all over China, such that most of the study participants were migrants. Among these migrant FEWs, sharing the same dialect and culture is a sign of homophily and thus may facilitate trust and bonding between them. The closeness between women from the same city/region was conducive to promoting the diffusion of intervention information:

“I met a ‘lao xiang’ (people from the same hometown) at the time. She found I was reading “100 Questions About Health” (a small booklet designed by the research team) and the other “lao xiang” said she also wanted one. Then, I called the intervention outreach worker to ask for more booklets. And then we all read it and everyone found it was so useful.” (FEW013, large venue, age 25, migrant, single, primary school education, 4 years in the industry)

Information being easily transmittable among people from the same hometown was frequently observed in our study. The natural similarity nurtured by the same local culture, facilitated by the same dialect, produces a natural network of communication. Many FEWs attributed their joining the study to the recommendation from other FEWs from the same city or region.

Apart from hometown fellows, the discussion of intervention materials was also very frequent and casual between friends. And these discussions were usually less confined by geographical location, as compared to discussions occurring between colleagues. One FEW described her intervention-related chatting with a close friend in her daily life:

“After the class, we were shopping in supermarket and then we saw a young couple there (buying condoms). She whispered to me: ‘Look, they are buying condoms.’ I chuckled: ‘It seems they also use condoms when having sex.’ And she said: ‘What do you think then? Who in the world does not have sex without wearing a condom nowadays?’” (FEW001, large venue, age 25, migrant, single, primary school education, 6 years in the industry)

When being asked with whom they would tend to share information learned in the intervention sessions, most FEWs gave a similar answer which was ‘people who are close to me’. Discussing issues related to sexual behavior, STDs, and condom use with colleagues was considered to be less awkward if it happened that the person was also a close friend.

Key Features of the Intervention to Optimize Information Diffusion Within Networks

Table 3 presents the key factors and corresponding activities that facilitated diffusion of the intervention material through existing networks within venues. Certain factors appeared to be more applicable to one type of venue as compared to others.

Personalized Approach Which Takes into Account Social Segmentation

In the initial stage of project development, based on the concept of ‘peer education’, elder females who were formerly FEWs were hired by the research team to start the project. It was assumed that these former FEWs would have access to this hard-to-reach population who were wary of outsiders due to the illegality of the sex trade. Contrary to our expectation, these senior peers were unable to successfully engage large venues as a result of refusals from venue owners. A potential reason for this might be the differential social status held by those former/retired FEWs and venue owners:

“Social status is very important. I remember one time we went to a venue and started talking to the owner. At the beginning everything went well, but suddenly he saw that Lee (a previous sex workers recruited by the project) was distributing cigarettes to FEWs, and that made him really annoyed. In the end we didn’t make it in that venue.” (FCLT01, age 55, retired sales woman)

Another outreach worker also expressed similar opinions and pointed out that:

“If you want the venue owner to take you seriously, be serious in positioning your social identity.” (FCLT02, age 55, retired physician)

In contrast to the venue owners, at the beginning a lower-profile approach was effective among FEWs to alleviate fear of participating in the project. As described by an interviewer: “One of the most cooperative participants suddenly stopped talking to us one day simply because she found out our co-investigator had appeared on a television show.” FEWs were lowest in the venue hierarchy and the most powerless group. They appeared to be extremely sensitive and distrustful of government-related personnel, including people from research institutions, due to concerns that their identities would be made public. Many of them described themselves as ‘being so scared’ when we first arrived at the venues.

Selling the ‘Relative Advantage’ of Promoted Behaviors

In order to stimulate the desire of FEWs to communicate and adopt intervention-promoted behaviors, a clear advantage of resorting to such behaviors must be established as compared to not adopting the behaviors. In our intervention, we highlighted the advantage of protected sex by relating it to financial gains, something that most FEWs cared the most due to their economic imperatives. Because of rising medical expenses, especially for people without adequate insurance, along with decreases in FEWs’ income due to the economy during the study period, adoption of safer sex appeared to resonate as having relative advantage:

“In the past if a client intended to give us 500 yuan, we might just wipe his body clean and wouldn’t use a condom. But now we no longer do this. With this small amount of money, I can’t even afford a doctor.” (FEW006, age 27, local resident, single, high school education, 3 years in the industry)

The outreach workers also described how they highlighted the potential for FEWs to prolong their career if they stayed healthy and how not having to go to the hospital would save them money. In the interviews, many FEWs have reported this idea of “balancing pros and cons” before negotiating the price with clients.

Such calculations of relative advantage were not easily appreciated by mammies, whose income to a large extent depends on the number of girls who agree to trade sex with clients. Safer sex interventions can thus reduce the frequency of sex trade among FEWs because many clients are not willing to use condoms. An outreach worker reflected upon the awkward situation she encountered due to the “success” of the intervention:

“Sometimes they (the FEWs) would become really afraid of getting HIV/AIDS and I remember one time after I gave our lectures, all FEWs in one venue suddenly stopped going out with clients (trading sex) because they were scared. During that period the mammy of that venue was really angry with me.” (FCLT01, age 55, retired physician)

Venue owners also do not experience a direct relative advantage resulting from safer sex practices, but they usually provided their support to the intervention more out of consideration for social image.

Frequent Cues for Communication from Outreach Workers

Although formally the intervention ended after 6 months, intervention outreach workers still returned to the venues regularly to maintain connections with FEWs and organize follow-up activities. Ongoing appearance of the outreach worker both reminded FEWs of the intervention and served as a stimulus that aroused attention and provoked discussions of the intervention materials among FEWs:

“She (the intervention outreach worker) came here very often. Every time she came, she would distribute condoms and people would notice her and ask us who she was. We were all senior employees (more experienced FEWs) and we remembered her words by heart, but even new venue members also paid special attention to her words.” (FEW003, large venue, age 26, migrant, single, high school education, 5 years in the industry)

The outreach workers also highlighted the importance of having key personnel who promoted safe-sex by repeating intervention information in order to sustain its impact so that it continued to be remembered and discussed in the FEWs’ daily conversations. She referred to such a process as “a monk chanting Buddhist scripture”: only constant chanting can prevent oblivion.

Appeals to Authority

The ‘appeal to authority’ is referred to as a logical fallacy in which people tend to believe a statement is true because it is made by an authority figure. Although there was a strong reluctance among FEWs to talk to authorities for fear of having their identities exposed, they tended to fall into this fallacy after the initial fear wore off. In fact, the respect conferred to “experts” or “authorities” was so strong that even clients of FEWs were influenced:

“Last time a client was not willing to use condoms and he was one of my frequent clients, I warned him that he might be infected by disease but he said: ‘You look very healthy.’ Then I told him that a lot of diseases cannot be detected through one’s appearance but he said I was talking rubbish. Finally, I said: ‘This is what those experts told us when they gave us classes.’ And he responded: ‘Oh really? No kidding?’ I said: ‘It’s even written in the manual they gave us. Let me show you.’ After I showed him what it is said in the manual, he started to believe me and eventually agreed to use condoms.” (FEW005, large venue, age 23, migrant, single, middle school education, 4 years in the industry)

When being asked to pick between peers and “experts” as potential intervention outreach workers, many participants expressed their preference for “experts”:

“I think the intervention sessions are better if delivered by ‘experts.’ Personally I prefer ‘experts.’ If you find some other FEWs to talk about these things with us I think they don’t really have that sense of authority and things they say would not be persuasive.” (FEW021, large venue, age 24, migrant, single, high school education, 5 years in the industry)

Whenever the information was not immediately accepted due to suspicion and doubt from other FEWs who also received the information, the outreach workers reputations as “experts” helped them from being ignored or dismissed and aided in successfully communicating the information to new FEWs.

Discussion

Through this study we identified several interpersonal communication networks that play a unique role in disseminating intervention information in both large and small entertainment establishments in Shanghai, China. Large venues enjoyed multiple levels of communication networks. Of note, the network formed by the venue owners and FEWs was a very efficient route for spreading intervention information. Mammies and FEWs also formed an efficient communication network, but given the nature of mammies’ priorities, this network did not function well in promoting diffusion of the intervention. Compared to large venues, communication in small venues was more direct and frequent but was also bounded by the small size of networks. Networks formed by close friends and between women from the same city or region were common types of networks through which diffusion of information took place, but difficulty in ascertaining information about their size and boundaries renders them difficult to be monitored in behavioral interventions. Different dynamics of diffusion of information in entertainment venues documented in the study offer important implications to public health interventions within entertainment venues.

It is important to note that the intervention sessions for venue owners and FEWs were specifically tailored to their expectations and needs. The value of a tailored approach to the intervention became particularly apparent in large venues due to the multi-layered management structure. The entertainment establishments operating under a hierarchical managerial structure render a single package intervention design sub-optimal if diffusion of organizational level information is to be achieved. For venue owners, intervention sessions may be individually delivered by people who are highly respected and have a positive social image from the very beginning. For female sex workers who are particularly wary of revealing their identities, intervention outreach workers with a lower-profile may have a better chance to win their trust in the initial stages. This approach is a partial reflection of the underlying concepts in social network segmentation [17]. It might be reasonable to assume that without such a personalized approach, it may not be possible for the intervention to diffuse through and across different social networks in entertainment venues.

Although the unexpected dynamic communication of intervention material among FEW networks in the current project provides some optimism regarding the acceptability and sustainability of a HIV-risk reduction intervention, it must be noticed that information dissemination in the current project happened under the condition whereby intervention outreach workers regularly visited the venues throughout the project. Generating cues regularly to stimulate communication is not a new approach in diffusion-of-innovation-related studies. For example in an AIDS prevention project based on opinion leaders, posters with attractive logos and lapel buttons for peer educators were used to stimulate opportunities to initiate peer conversations in gay bars [23]. It is expected that the frequency of intervention-related communication within networks will wane once of the continuation of communication cues can no longer be guaranteed. We therefore recommend that intervention projects be designed in collaboration with local health organizations, which can sustain the intervention activities.

Peer education has been promoted widely as a primary strategy for interventions among hard-to-reach high-risk populations including commercial sex workers [24, 25], but interestingly in the current study we observed that information given by peers was not always taken at face value. A systematic study of HIV/AIDS prevention programs in Thailand, found that among the more effective programs, a certain degree of heterophily between target population and outreach workers, with the latter being more knowledgeable than the former, was desired by the target population [26]. As reflected by the well-known “appeal to authority”, people are often less likely to question messages from “authorities” while information from peers within social networks may be more likely to be accepted, especially when the information is considered novel to the receiver. We suggest that in certain cultural and social settings where less trust exists within particular groups of people, peer-led education would better optimize its impact if assisted by "experts" who are respected as having enough authority.

The difference between owners and mammies in terms of their level of support for HIV-related intervention activities in large venues is also noteworthy. Diffusion of organizational-level information achieved through venue gatekeepers may maximize the cost-effectiveness of interventions in large entertainment venues [19]. However, our results suggest that mammies are less willing to engage in key roles in intervention dissemination compared to venue owners. Venue owners are influenced by the social image of their venues. In addition, a major source of profits for most large venues is selling alcohol [27], so venue owners may not foresee a significant decline in the venue’s overall profitability after the implementation of the intervention. Nevertheless, mammies on the one hand do not own the venue and thus care less about its social image, and on the other hand, their income relies solely on the FEWs who work for them, i.e. the more clients accepted by FEWs the more money they receive. Therefore, any message that has a potential to reduce the number of clients would not be welcomed. As our intervention promoted condom use, an activity not favored by many clients, and disseminated information about HIV infection, a message that scared many FEWs into not accepting clients, mammies tended to see few benefits in supporting our activities. Therefore although in theory mammies are in a favorable position to mentor FEWs about the importance of condom use, they are not willing to take on such responsibility for fear of losing income. We recommend future interventions in commercial sex settings to be readily prepared for potential barriers from FEW gatekeepers and to be mindful of the sources of their negative attitudes toward HIV behavioral interventions. In addition, all interventions that intend to take advantage of gatekeepers’ influence in diffusing information may benefit from a preliminary ethnographic study of the target population to better understand the potential of such an approach.

Despite the fact that venue owners were easier to motivate in our intervention, the lack of a compelling benefit for gatekeepers in adopting the intervention rendered their support for our intervention very unstable. Such a lack of motivation among gatekeepers is mainly due to the incompatibility between the goals of intervention team (i.e. promoting the adoption of safer sexual behavior with clients among FEWs) and what is valued by the gatekeepers (an emphasis on the satisfaction of clients at any price). Because gatekeepers typically do not take responsibility for the health of FEWs, HIV-related interventions are unable to accommodate the value system of gatekeepers. Therefore, we suggest the establishment of structural and societal support for FEWs to adopt safe sex behaviors. Such support can come in the form of a penalty and reward system for venue owners based on incidence of STIs, which would help to motivate reduction in sexual risk behaviors from the gatekeepers. Furthermore, any intervention activities that aim to influence gatekeepers’ influence on the target population must fit with the goal of intervention and with the value system of the gatekeepers in addition to that of the target population.

As in all qualitative studies, this study is limited by its relevance to settings that are different from where the study was conducted, such as countries where commercial sex has been decriminalized. Caution must also be used when additional themes generated from this study and outside the predefined categories in the diffusion of innovation framework are to be applied to other populations. Nonetheless, the findings are particularly relevant to similar settings within China, in which to date little research on diffusion of innovation among FEWs has been conducted. In the current study, sex workers from small venues are clearly underrepresented and the little number of people interviewed made us unable to assess whether we reached saturation of information for small venues.

Conclusions

Results of the current study suggest that interpersonal networks are readily available in entertainment venues to assist venue-level diffusion of safe sex interventions. The incompatibility between safer sex and business profitability obstructs communication through mammies, but venue owners concerned with their social image are able to take on the role of intervention disseminators. Information diffusion was easily attainable in small venues due to the simpler management structure, but intervention effects may be more easily scaled up in large venues due to relatively larger number of employees.

Apart from taking advantage of the dynamics of information diffusion within venues, our analysis also suggests factors can be anticipated that might help or hinder diffusion of intervention activities in China and help tailor the intervention activities to particular social and environmental contexts. Although the current study has identified several factors that played a role in diffusion of intervention in the Chinese context, it is recommended that future studies in other settings undertake a similar assessment of the intervention context to maximize the impact of these interventions.

As behavior patterns of a population are a product of hierarchically distributed social conditions resulting from structural influences of society, behavioral interventions at the personal or venue level can hardly be sustained without structural changes, such as policy reform (e.g. the introduction of an employer liability system to make safer sex a priority of the entertainment venues themselves, and thus a truly sustainable behavior). Thailand’s 100 % condom use program is a good example of structural reform [28]. Yet similar pilot programs in China struggled between the policy of “cracking down on sex work” and the practice of “promoting condom use among sex workers” [28–30]. We therefore call for efforts to improve the policy environment in China to facilitate public health initiatives to promote safe sex among FEWs.

References

Hong Y, Li XM, Yang HM, Fang XY, Zhao R. HIV/AIDS-related sexual risks and migratory status among female sex workers in a rural Chinese county. Aids Care. 2009;21(2):212–20.

Settle E. AIDS in China: An Annotated Chronology. 2003.

Huang YY, Henderson GE, Pan SM, Cohen MS. HIV/AIDS risk among brothel-based female sex workers in China: assessing the terms, content, and knowledge of sex work. Sex Transm Dis. 2004;31(11):695–700.

Hong Y, Fang XY, Li XM, Liu Y, Li MQ. Environmental support and HIV prevention behaviors among female sex workers in China. Sex Transm Dis. 2008;35(7):662–7.

Chen XS, Yin YP, Liang GJ, Gong XD, Li HS, Shi MQ, et al. Co-infection with genital gonorrhoea and genital chlamydia in female sex workers in Yunnan, China. Int J Std Aids. 2006;17(5):329–32.

Gil VE, Wang MS, Anderson AF, Lin GM, Wu ZJO. Prostitutes, prostitution and STD/HIV transmission in mainland China. Soc Sci Med. 1996;42(1):141–52.

USAIDS. China Epidemic & Response. 2010 [cited 2011 April, 1]. Available from: http://www.unaids.org.cn/en/index/page.asp?id=197&class=2&classname=China+Epidemic+%26+Response.

Ngugi EN, Chakkalackal M, Sharma A, Bukusi E, Njoroge B, Kimani J, et al. Sustained changes in sexual behavior by female sex workers after completion of a randomized HIV prevention trial. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;45(5):588–94.

Rogers EM. Diffusion of preventive innovations. Addict Behav. 2002;27(6):989–93.

Latkin CA, Knowlton AR. Micro-social structural approaches to HIV prevention: a social ecological perspective. Aids Care. 2005;17:S102–13.

Winett RA, Anderson ES, Desiderato LL, Solomon LJ, Perry M, Kelly JA, et al. Enhancing social diffusion-theory as a basis for prevention intervention—a conceptual and strategic framework. Appl Prev Psychol. 1995;4(4):233–45.

Dearing JW, Meyer G, Rogers EM. Diffusion theory and HIV risk behavior change. In: Diclemente RJ, Peterson J, editors. Preventing AIDS: theories and methods of behavioral interventions. New York: Plenum Press; 1994. p. 79–93.

Latkin C, Donnell D, Celentano DD, Aramrattna A, Liu TY, Vongchak T, et al. Relationships Between Social norms, social network characteristics, and HIV risk behaviors in Thailand and the United States. Health Psychol. 2009;28(3):323–9.

Caceres CF, Celentano DD, Coates TJ, Hartwell TD, Kasprzyk D, Kelly JA, et al. Results of the NIMH Collaborative HIV/sexually transmitted disease prevention trial of a community popular opinion leader intervention. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;54(2):204–14.

Rogers EM. A prospective and retrospective look at the diffusion model. J Health Commun. 2004;9:13–9.

Aral S. Identifying social influence: a comment on opinion leadership and social contagion in new product diffusion. Market Sci. 2011;30(2):217–23.

Valente TW, Fosados R. Diffusion of innovations and network segmentation: the part played by people in promoting health. Sex Transm Dis. 2006;33(7):S23–31.

Bertrand JT. Diffusion of innovations and HIV/AIDS. J Health Commun. 2004;9:113–21.

Yang HM, Li XM, Stanton B, Fang XY, Zhao R, Dong BQ, et al. Condom use among female sex workers in China: role of gatekeepers. Sex Transm Dis. 2005;32(9):572–80.

Yang XS, Xia GM, Li XM, Latkin C, Celentano D. The efficacy of a peer-assisted multi-component behavioral intervention among female entertainment workers in China: an initial assessment. Aids Care. 2011;23(11):1509–18.

Bernard HR. Research methods in anthropology: qualitative and quantitative approaches. 4th ed. Walnut Creek: AltaMira Press; 2005.

ATLAS.ti. Version 4.2. Berlin: Scientific Sofware Development; 1999.

Kelly JA, Lawrence JSS, Diaz YE, Stevenson LY, Hauth AC, Brasfield TL, et al. Hiv risk behavior reduction following intervention with key opinion leaders of population—an experimental-analysis. Am J Public Health. 1991;81(2):168–71.

Ford K, Wirawan DN, Suastina W, Reed BD, Muliawan P. Evaluation of a peer education programme for female sex workers in Bali, Indonesia. Int J STD AIDS. 2000;11(11):731–3.

Rickard W, Growney T. Occupational health and safety amongst sex workers: a pilot peer education resource. Health Educ Res. 2001;16(3):321–33.

Svenkerud PJ, Singhal A. Enhancing the effectiveness of HIV/AIDS prevention programs targeted to unique population groups in Thailand: lessons learned from applying concepts of diffusion of innovation and social marketing. J Health Commun. 1998;3(3):193–216.

Harcourt C, Donovan B. The many faces of sex work. Sex Transm Infect. 2005;81(3):201–6.

Rojanapithayakorn W, Hanenberg R. The 100% condom program in Thailand. AIDS. 1996;10(1):1–7.

Yang HT, Du YP, Ding JP, Qian WJ, Li L, Zhou ZL et al. Evaluation of the “Jiangsu/WHO 100% condom use programme in China”. Zhonghua liu xing bing xue za zhi. 2005;26(5):317–20.

Zhongdan C, Schilling RF, Shanbo W, Caiyan C, Wang Z, Jianguo S. The 100% condom use program: a demonstration in Wuhan, China. Eval Program Plann. 2008;31(1):10–21.

Acknowledgments

Funding for the research was provided through National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Grant 1R01HD050176. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. The authors would also like to thank Ines Bustamante for translating the abstract into Spanish.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, Y., Latkin, C., Celentano, D.D. et al. Delineating Interpersonal Communication Networks: A Study of the Diffusion of an Intervention Among Female Entertainment Workers in Shanghai, China. AIDS Behav 16, 2004–2014 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-012-0214-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-012-0214-1