Abstract

Female drug users report greater psychopathology and risk behaviours than male drug users, putting them at greater risk for HIV. This mixed-methods study determined psychiatric, behavioural and social risk factors for HIV among 118 female drug users (27% (32/118) were HIV seropositive) in Barcelona. DSM-IV disorders were assessed using the Spanish Psychiatric Research Interview for Substance and Mental Disorders. 30 participants were interviewed in-depth. In stepwise multiple backward logistic regression, ever injected with a used syringe, antisocial personality disorder, had an HIV seropositive sexual partner and substance-induced major depressive disorder were associated with HIV seropositivity. Qualitative findings illustrate the complex ways in which psychiatric disorders and male drug-using partners interact with these risk factors. Interventions should address all aspects of female drug users’ lives to reduce HIV.

Resumen

Las mujeres consumidoras de drogas presentan más psicopatología y conductas de riesgo que los consumidores, exponiéndolas a un riesgo mayor de contraer la infección por el VIH. El objetivo del presente estudio fue evaluar, mediante metodología mixta, los factores de riesgo psiquiátricos, comportamentales y sociales para la infección por el VIH en 118 mujeres consumidoras de drogas (27% (32/118) seropositivas para el VIH) en Barcelona. Los trastornos psiquiátricos (según criterios DSM-IV) se evaluaron mediante la versión española de la Psychiatric Research Interview for Substance and Mental Disorders. Se entrevistaron a 30 mujeres en profundidad. En la regresión logística, los factores que se asociaron a la infección por el VIH fueron la inyección con jeringuillas usadas previamente, tener el trastorno de personalidad antisocial, una pareja sexual con infección por el VIH y tener una depresión mayor inducida por sustancias. Los análisis cualitativos ilustraron la complejidad con que los trastornos psiquiátricos y las parejas consumidoras interactúan con estos factores de riesgo. Las intervenciones diseñadas para reducir la infección del VIH deberían abordar diferentes aspectos de la vida de las mujeres usuarias de drogas.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Worldwide, around one in six injecting drug users (IDU) have HIV [1]. Female IDU are at higher risk than male IDU for HIV [2]. Female drug users report risk behaviours including sharing needles and injecting paraphernalia, having sex with IDU, having HIV seropositive (+ve) sexual partners, sex trading and not using condoms [3–5], potentially putting them at greater risk of exposure to HIV than their male counterparts. In longitudinal studies among female drug users, sex trading, younger age, cocaine injecting, requiring help injecting, having unsafe sex with a regular partner and having an HIV+ve sexual partner were associated with seroconversion [2, 6].

The prevalence of psychiatric disorders is consistently higher among female than male drug users [7, 8]. Seroprevalence studies report HIV infection rates 13–76 times higher among women with severe and persistent mental illnesses than among the general population [9]. Drug users with comorbid mental disorders report: greater sharing of injection equipment, lower rates of condom use, multiple partners, sex trading, and having sex with an IDU [9–12]. Depressive symptoms are also associated with drug [13–15] and sexual risk behaviours [16, 17].

Systematically, studies report a higher prevalence of intimate partner violence (IPV) among female drug users than among non drug users. Among HIV+ve women or women at risk of HIV, the prevalence of IPV varies from 30 to 67%, around three times greater than in the general population [18]. Women who have experienced IPV are less likely to use condoms; and more likely to share needles, to have multiple sexual partners and to trade sex [18, 19]. Therefore, IPV could increase HIV vulnerability [19].

Despite what is already known, no study has considered all identified risk factors together in one study to determine their association with HIV. The current study examined psychiatric, behavioural and social risk factors for HIV infection among female drug users using mixed methods.

Methods

Design

A mixed methods design was employed. In Phase 1, a cross-sectional study was conducted among female drug users attending drug treatment services. In Phase 2, in-depth qualitative interviews were conducted with participants who had completed Phase 1.

Participants and Setting

During March 2008 to December 2009, a convenience sample of 166 female drug users from five outpatient drug abuse centres, two inpatient detoxification units, a dual diagnosis inpatient unit and a non government organisation in Barcelona, Spain were eligible to participate in Phase 1. Inclusion criteria were: aged 18 or above, ability to communicate in Spanish or Catalan, attending drug treatment and consenting to the treatment facility sharing their latest HIV and hepatitis C blood test results with the researcher. Females with alcohol dependence alone were excluded from the study.

In Phase 2, 30 participants (15 HIV+ve) were interviewed in-depth. The sample was purposively generated and stratified by factors of influence including substance of misuse, psychiatric disorders, sex trading, IPV and risk behaviours to generate the maximum range of perspectives and experiences [20]. The sample size in each group was large enough for comparison and saturation, usually occurring around 12–15 interviews [21].

Procedure

Ethics Approval was Granted by the Institute’s Human Research Ethics Committee.

Eligible participants were approached by researchers in outpatient waiting rooms and via a non government organisation website. In addition, staff determined patients’ interest in discussing the study with a researcher. Participants were given a study information sheet that was explained by the researcher. Signed informed consent was sought from all participants for each study phase. Questionnaires and interviews were conducted in a private room by trained researchers. Participants recruited from outpatient services received a 20€ gift-voucher on completion of each phase.

Instruments

Substance use disorders, major depressive disorder (independent and substance-induced), post traumatic stress disorder, antisocial personality disorder and borderline personality disorder were diagnosed by trained researchers using the Spanish Psychiatric Research Interview for Substance and Mental Disorders (PRISM) [22], a reliable semi-structured interview developed to assess DSM-IV Axis I and Axis II disorders among substance users [22–24]. Lifetime disorders are reported. The PRISM differentiates between the expected effects of intoxication and withdrawal, and between independent and substance-induced disorders [25].

Seven personality dimensions: novelty seeking, harm avoidance, reward dependence, persistence, self directedness, cooperativeness and self transcendence; were assessed with the Spanish Temperament and Character Inventory-Revised [26].

Four dimensions of IPV: severe combined abuse, emotional abuse, physical abuse, and harassment were examined in the previous 12 months or in their previous relationship, using the 30-item Composite Abuse Scale [27]. Each item requires a response to the frequency of occurrence in the previous 12 months: “never”, “only once”, “several times”, “monthly”, “weekly” or “daily”. Good internal reliability has been demonstrated [28].

General assertiveness was assessed using the 30-item Rathus Assertiveness Schedule [29]. Sixteen items are reversed to reduce response bias. Each item is rated on a 6-point scale, from −3 (very uncharacteristic) to +3 (very characteristic). Total scores vary from −90 to 90, with lower scores indicating lower assertiveness. High reliability and concurrent and predictive validity have been reported [30–32].

Initiation, refusal, and contraception-sexually transmitted disease (STD) prevention assertiveness were reliably assessed with the Sexual Assertiveness Scale for Women [33].

HIV risk behaviours in the previous month were determined using the drug use and sexual behaviour sub-sections of the 11-item HIV Risk-taking Behaviour Scale [34]. Three scores are calculated: a total score indicating level of HIV risk-taking behaviour; a “drug use” and a “sexual behaviour” risk sub-total. The higher the score, the greater the risk of contracting or transmitting HIV.

With the exception of the interviewer-administered PRISM; all other instruments were interviewer-administered or self-completed depending on participants’ literacy abilities. Researchers checked for missing data with participants on self-completed questionnaires. Where instruments were not available in Spanish, back translations were undertaken and approved by the original authors.

In-depth Interview Topic Guide

The topic guide invited participants to discuss their HIV risk behaviours, and describe situations where they were more likely to exhibit such behaviours. The average duration of the interview was 62.26 min (SD 18.73).

Statistical Analyses

Quantitative data were analysed using SPSS [35]. Percentages were calculated on actual responses. Differences between HIV risk taking behaviours, assertiveness and personality traits by HIV infection were calculated using t-tests for continuous data. Odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were calculated by logistic regression to determine risk factors for HIV. Clinically relevant variables (borderline personality disorder and post traumatic stress disorder) and variables significant (P < 0.05) at univariate analysis (unprotected sex; primary versus; substance-induced major depression; antisocial personality disorder; number of drug abuse or dependence disorders; ever injected with used syringe; ever been in prison; ever sex traded; ever homeless; and ever had an HIV+ve partner) were entered into the backward stepwise multiple logistic regression analyses to ascertain the model associated with HIV. A total of 12 variables were entered into the model. Age was not included as older participants were more likely to have been exposed to the HIV epidemic in Spain. The drug use risk subscale from the HIV Risk Behaviour Scale score was not entered into the model as it assessed drug related risk in the previous month. Instead “ever injected with used syringe” was included. Similarly, lifetime post traumatic stress was entered and not past year intimate partner violence. The Contraception/STD Prevention Scale score from the Sexual Assertiveness for Women Scale was not entered into the model as participants were asked to respond with their usual sexual partner in mind and therefore their current contraception/STD prevention behaviour may have changed following their diagnosis of HIV.

Analysis of Qualitative Data

In-depth interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim. Data were organized and coded using NVivo [36]. A qualitative research framework approach was used for the analysis: familiarisation, identifying a thematic framework, indexing, charting and mapping and interpretation [37].

Results

Phase 1

Of the total 166 eligible participants; 118 completed the assessment: 77 from outpatient drug abuse centres, 27 from inpatient detoxification units, eight from the dual diagnosis inpatient unit and six from the non government organisation. In addition; 19 partially completed assessments were not included in the analysis and 29 participants refused to participate, mainly due to disinterest, lack of time or feeling unwell. There was no differences in age (39.07 vs. 40.06 years; t(117) = −1,386; P = 0.168) between those who did and did not complete the assessment. However, those who completed the assessment were more likely to be HIV seropositive (27.1% (95% CI 19.0–35.26%) vs. 17.6%; P = 0.306).

Clinical records reported that 27.1% (32/118) were HIV+ve and 46.6% (55/118) were hepatitis C+ve. The majority of participants were white (96.6%) with a mean age of 39.07 years (SD 7.75).

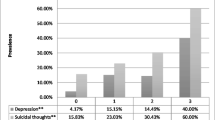

Lifetime Mental and Substance Use Disorders (SUD), and Lifestyle Factors by HIV Infection (Table 1)

HIV+ve participants were older. The odds of being HIV+ve were over three times greater for participants who met criteria for substance-induced major depressive disorder (OR 3.37; 95% CI 1.42, 7.97) and over five times greater for those who met criteria for antisocial personality disorder (OR 5.44; 95% CI 2.16, 13.71). The mean number of SUD was significantly greater among HIV+ve participants (OR 1.52; 95% CI 1.15, 2.00). The odds of being HIV+ve were greater among those who met criteria for abuse or dependence on heroin (OR 31.00; 95% CI 4.05, 237.38) and sedatives (OR 3.51; 95% CI 1.50, 8.22). The odds of having an HIV+ve (OR 23.38; 95% CI 6.18, 88.44) or an IDU partner (OR 10.78; 95% CI 2.39, 48.72), having regularly injected (OR 13.27; 95% CI 4.24, 41.54) or having injected with a used syringe (OR 17.11; 95% CI 5.76, 50.76), or sexual risk behaviours (unprotected sex OR 2.87; 95% CI 1.23, 6.69; ever traded sex OR 7.35; 95% 2.94, 18.39) were greater among HIV+ve participants.

HIV Risk Taking Behaviours, Assertiveness and Personality Traits by HIV Infection (Table 2)

HIV+ve participants scored higher on the drug use sub-section of the HIV Risk Behaviour Scale than HIV−ve participants (1.41 vs. 0.30; t(114) = −3.015; P = 0.003), but not in the sexual behaviour sub-section (2.03 vs. 3.13; t(114) = 1.539; P = 0.127). HIV+ve participants reported greater assertiveness only with regards to contraception and STD prevention on the Sexual Assertiveness for Women Scale (17.63 vs. 14.58; t(114) = 3.894; P < 0.001). No differences were found in general assertiveness or in personality traits by HIV infection.

Factors Associated with HIV Infection (Table 3)

In stepwise multiple backward logistic regression, having ever injected with a used syringe (OR 14.06; 95% 2.57, 77.06), antisocial personality disorder (OR 9.47; 95% CI 1.34, 66.94), having ever had an HIV+ve sexual partner (OR 6.36; 95% CI 1.21, 33.40) and lifetime substance-induced major depressive disorder (OR 6.02; 95% CI 1.19, 30.46) remained significant in the model associated with HIV.

Phase 2

Thirty participants (15 HIV+ve) were interviewed in-depth. The mean age of HIV−ve patients was 39.57 years (SD 7.84) and 41.11 years (SD 5.58) for HIV+ve patients.

For the purpose of this paper, only psychiatric, behavioural, social and risk factors are considered.

Injecting Risk Behaviours

Limited access to clean equipment or out of desperation to stop withdrawal had resulted in sharing syringes (e.g. incarceration, homelessness). Many described injecting with and being injected by their male sexual partner. Often this was viewed more positively than sharing with others. Such relationships often resulted in potentially greater injecting risks for female partners “he (husband) did it first (injected) because he was selfish like that” (ID 52, 54 years, IDU, HIV−ve, substance-induced major depressive disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder).

Although participants did not frequently directly relate their injecting risk behaviours to their mood; a sense of fatalism was evident in risk taking behaviours.

“When I had a partner I shared, but I have only had three partners” (two of whom were HIV+ve)… we shared just the same… given we were using, we were killing ourselves anyway” (ID 132, 35 years, IDU, HIV+ve, substance-induced major depressive disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, antisocial and borderline personality disorder).

Sexual Risk Behaviours

While participants’ discourses were often inconsistent, they believed they were more likely to have used condoms with casual than with stable partners, considering less HIV risk from stable partners. Reasons for non condom use with stable partners centred on love and intimacy. Furthermore, several HIV+ve participants demonstrated a lack of assertiveness in choosing to protect themselves or their partner; believing their responsibility was limited to disclosing their HIV status.

“if it is an occasional (partner) …definitely condom …I have had partners for five years, I told them (that I had HIV) but unfortunately I gave it to two guys but they knew… they told me they didn’t care… that they didn’t want to (use a condom) that if they have to die anyway that’s what they said to me… they didn’t care they knew… I’ll be happy to do it (without a condom), but always at least I try not to do it during my period… once they didn’t want to (use a condom) only a few times this has happened to me…I didn’t tell them (I was HIV+ve)…its that someone you don’t know and that you aren’t going to see again in your life and you’re not doing it when you’ve got your period because there is a much greater (HIV transmission) risk with blood…they’ll be ok…without a condom is when I have a stable partner. I try to use condoms (with occasional partners) but I don’t tell them I’ve got anything… otherwise there’s no sex…Can you say with your hand on your heart that you always use condoms? Nearly always … after telling him (that I’m HIV+ve) if he doesn’t want to I can’t make him put one on Why not? Because if they don’t want to, what do you want me to do? I can’t make him. But you continue to have sex or…Yes I carry on because they tell you, “no no I love you just as you are and I don’t care what you’ve got” (ID 21, 43 years, IDU, HIV+ve, substance-induced major depressive disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, borderline personality disorder).

Several participants commented that their mood affected their condom use.

“I wanted to kill myself somehow, I didn’t want to use a knife or a gun but I wanted to disappear (I didn’t use condoms with HIV+ve partner because) … I was in a down phase of bipolar, I wasn’t up (euphoric) and I wanted to kill myself or hurt myself in some way” (ID 113, 46 years, IDU, HIV−ve, post-traumatic stress disorder, borderline personality disorder).

Sex trading put participants at greater risk of HIV infection or transmission out of desperation for the need for drugs.

“the truth is that (there are sexual behaviours that put you at greater risk of getting HIV), but then, if they (clients) pay more… for anal sex …without protection… but for (more) money… you give in, you give in because the need for drugs is greater” (ID 14, 34 years, IDU, HIV+ve, post-traumatic stress disorder, borderline personality disorder).

“…if it was (sex) for money I used a condom and if it was for heroin I didn’t…those who sell drugs… don’t want condoms …you’re not in a position to negotiate (due to) withdrawal” (ID 132, 35 years, IDU, HIV+ve, substance-induced major depressive disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, borderline and antisocial personality disorder).

IPV also impacted on participants’ abilities to negotiate safer sex.

“an abuser will never use a condom, you are his possession, you are his, he will do what he wants with you …if you don’t have sex he will do it anyway ….if you don’t want to (have sex) you will get a beating” (ID 32, 35 years, IDU, HIV−ve, post-traumatic stress disorder, borderline and antisocial personality disorder).

Discussion

Among female drug users in substance abuse treatment, HIV infection was associated with having ever injected with a used syringe, antisocial personality disorder, having ever had an HIV+ve sexual partner and substance-induced major depressive disorder. These findings were supported by the qualitative findings. This study was the first to examine all previously identified HIV risk factors together in one model to determine the weight of each risk factor. This model highlights the importance of psychopathology and risk behaviours in the context of female drug users’ relationships with male partners.

Psychiatric Risk Factors

Participants who were poly substance users, met criteria for heroin or sedative use or dependence disorder, substance-induced major depressive disorder and antisocial personality disorder had greater odds of being HIV+ve. The relationship between heroin and HIV in the sample was likely due to heroin being the most commonly injected drug at the outbreak of the HIV epidemic in Spain. More recently, others have reported an association between HIV and poly substance and sedative use disorders [38] potentially due to the higher risk of injecting by female drug users who are both poly substance users and dependent on illicit tranquilisers [39]. The relationship between sedative use and HIV in our study may be the result of attempts to self-medicate negative mood [39, 40] given the higher prevalence of substance-induced mood disorders reported among HIV+ve participants.

While previous studies have demonstrated the association between depressive symptoms and sexual [16, 17] and drug use risk behaviours [13–15], none have differentiated between substance-induced and independent depressive disorders. Stein et al. [13] argue that depression may “increase HIV risk by affecting drug users’ sense of fatalism, with hopelessness overwhelming the perceived benefits of behaviour change; depression may lead to increased drug use, secondarily increasing HIV risk; depression may also affect risk avoidance planning as injectors need to acquire clean needles before the time of injection”. This was evident in the qualitative interviews, especially among HIV+ve participants.

Similar to an earlier study among IDU [41], we found an association between antisocial personality disorder and HIV among female drug users, which had not previously been studied. Antisocial personality disorder has been associated with higher HIV risk behaviours which may account for the higher HIV infection among those with this disorder [12, 42, 43]. Drug users with antisocial personality disorder potentially lack consideration or devalue the longer term consequences of their actions, resulting in participating in immediately gratifying activities [44]. In addition, greater psychiatric comorbidity, especially depression, has been reported among drug users with antisocial personality disorder which may independently increase HIV risk behaviours [8].

We found no differences by HIV infection in the seven personality dimensions measured. Higher scores in novelty seeking and harm avoidance have been reported among HIV+ve drug users versus healthy controls [45]; however, no study has compared these personality dimensions among female drug users by HIV infection.

Behavioural Risk Factors

Unprotected sex, sex trading, injecting regularly, injecting with a used syringe, having ever had an IDU partner and having ever had an HIV+ve partner were associated with HIV infection. Furthermore, HIV+ve participants reported significantly greater drug use risks in the previous month on the HIV Risk-taking Behaviour Scale than their HIV−ve counterparts, highlighting continuing risk behaviours.

Findings from the qualitative interviews demonstrate that HIV risk behaviour should be understood in the context of female drug users’ sexual and drug using relationships with male partners [46]. Female IDU are more likely than male IDU to have sexual partners who also inject drugs, to share needles and injecting paraphernalia with their sexual partner [47]. Having an HIV+ve sex partner is associated with HIV seroconversion [48]. Female drug users report sharing with their partners, when they desire love, trust and intimacy in the relationship [49]. These findings were supported in our qualitative findings. Many participants reported being in a stable relationship, and perceived less risk in these relationships [48].

There was no difference in general assertiveness by HIV status. Only the contraception-STD prevention scale of the Sexual Assertiveness for Women Scale was significantly different for participants with and without HIV. Similar to other research [50], HIV+ve participants were more likely to use contraception in their sexual relationships potentially due to their HIV transmission knowledge. However, the qualitative interviews highlight that participants were not always assertive in their decisions about ensuring they practiced safe sex or in taking responsibility for informing (casual or commercial) partners of their HIV status. Male partners were often ambivalent about the possibility of becoming infected with HIV, suggesting the need to address HIV sexual risk prevention among male drug users.

Similar to other studies, sex trading was associated with HIV infection [51]. Several participants, many of whom were HIV+ve, described accepting more money for unprotected sex through desperation for money or drugs; and stressed that unprotected sex with drug dealers was the norm. This relationship could also be a result of the greater psychopathology among female drug users who are sex trading compared to those who are not [5].

Social Risk Factors

Participants with HIV were older, potentially due to injecting before the introduction of harm reduction programmes in Spain. Although there was no significant difference in the proportion of participants who had experienced IPV by HIV infection, qualitative interviews with HIV+ve participants highlight that abusive male partners impacted on their ability to negotiate safer sex. Around half of male drug users in treatment report perpetrating IPV [52]. Given that many female drug users have male drug using partners, the potential for HIV transmission is likely to be high among female drug users who experience IPV [19]. IPV is associated with needle-sharing and non condom use, potentially due to the negative control of the perpetrator [19].

Being homeless and ever being imprisoned were not statistically associated with HIV in this study, however, qualitative findings illustrate the risks taken by female drug users resulting from a lack of access to clean needles and condoms.

Implications for Treatment

The findings highlight the need for HIV prevention interventions that address female drug users’ multiple and complex needs including negative mood, antisocial personality disorder and risks incurred in intimate relationships.

Promising results have been reported with regards to reducing HIV risk behaviours [53]. Addressing coping skills and trauma among female drug users reduces HIV risk behaviours [54]. In addition, couples-based HIV prevention interventions among IDU may be effective in reducing risk behaviours while enhancing intimate relationships [55]. Interventions focused on improving self-esteem and depression among female drug users who have experienced IPV could help mitigate its impact and in turn, the risk of HIV [19]. There remains a need to develop and test interventions that holistically address all aspects of female drug users’ lives to reduce risk taking behaviours and HIV [56].

Limitations

This study has several limitations. Firstly, patients were not randomly recruited potentially limiting the generalisability of the findings. However, such limitations should be considered against the difficulties of recruiting hard to reach groups [57]. Secondly, despite numerous efforts to recruit participants, only 118 assessments were completed. The small sample size may have increased the possibility of type II errors. Lastly, as many of the participants in the study had ceased injecting this is reflected in the drug use sub-section of the HIV Risk Behaviour Scale. Despite these limitations, it is the first study to model the contribution of previously studied psychiatric, behavioural and social risk factors for HIV among female drug users.

Conclusions

The findings illustrate the multiple pathways to HIV infection and risk-taking behaviours, and the complex ways in which psychiatric disorders and male drug-using partners may interact with each risk factor.

References

Mathers BM, Degenhardt L, Phillips B, et al. Global epidemiology of injecting drug use and HIV among people who inject drugs: a systematic review. Lancet. 2008;15:1733–45.

Strathdee SA, Galai N, Safaiean M, et al. Sex differences in risk factors for hiv seroconversion among injection drug users: a 10-year perspective. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:1281–8.

Dwyer R, Richardson D, Ross MW, Wodak A, Miller ME, Gold JA. Comparison of HIV risk between women and men who inject drugs. AIDS Educ Prev. 1994;6:379–89.

El-Bassel N, Simoni JM, Cooper DK, Gilbert L, Schilling RF. Sex trading and psychological distress among women on methadone. Psychol Addict Behav. 2001;15:177–84.

Gilchrist G, Gruer L, Atkinson J. Comparison of drug use and psychiatric morbidity between prostitute and non-prostitute female drug users in Glasgow, Scotland. Addict Behav. 2005;30:1019–23.

O’Connell JM, Kerr T, Li K, et al. Requiring help injecting independently predicts incident HIV infection among injection drug users. J AIDS. 2005;40:83–8.

Krausz M, Degkwitz P, Kühne A, Verthein U. Comorbidity of opiate dependence and mental disorders. Addict Behav. 1998;23:767–84.

Torrens M, Gilchrist G, Domingo-Salvany A. Psychiatric comorbidity in illicit drug users: substance induced versus independent disorders. Drug Alcohol Depend (in press).

Carey M, Carey K, Kalichman S. Risk for human immuno-deficiency virus (HIV) infection among persons with severe mental illnesses. Clin Psychol Rev. 1997;17:271–91.

Dinwiddie SH, Cottler L, Compton W, Abdallah AB. Psychopathology and HIV risk behaviors among injection drug users in and out of treatment. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1996;43:1–11.

Meade CS. Sexual risk behavior among persons dually diagnosed with severe mental illness and substance use disorder. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2006;30:147–57.

Disney E, Kidorf M, Kolodner K, et al. Psychiatric comorbidity is associated with drug use and HIV risk in syringe exchange participants. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2006;194:577–83.

Stein MD, Anderson BJ, Solomon DA, Herman DS, Ramsey SE, Brown RA. Reductions in HIV risk behaviors among depressed drug injectors. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2005;31:417–32.

Kang S, De Leon G. Correlates of drug injection behaviors among methadone outpatients. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 1993;9:107–18.

Mandell W, Kim J, Latkin C, Suh T. Depressive symptoms, drug network, and their synergistic effect on needle-sharing behavior among street injection drug users. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 1999;25:117–27.

Morrill AC, Kasten L, Urato M, Larson MJ. Abuse, addiction, and depression as pathways to sexual risk in women and men with a history of substance abuse. J Subst Abuse. 2001;13:169–84.

Williams CT, Latkin CA. The role of depressive symptoms in predicting sex with multiple and high-risk partners. J AIDS. 2005;38:69–73.

El-Bassel N, Gilbert L, Wu E, Go H, Hill J. Relationship between drug abuse and intimate partner violence: a longitudinal study among women receiving methadone. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:465–70.

Wagner KD, Hudson SM, Latka MH, et al. The effect of intimate partner violence on receptive syringe sharing among young female injection drug users: an analysis of mediation effects. AIDS Behav. 2009;13:217–24.

Mays N, Pope C. Rigour in qualitative research. BMJ. 1995;311:109–12.

Guest G, Bunce A, Johnson L. How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods. 2006;18:59–82.

Torrens M, Serrano D, Astals M, Perez-Domınguez G, Martın-Santos R. Diagnosing psychiatric comorbidity in substance abusers validity of the Spanish versions of psychiatric research interview for substance and mental disorders (PRISM-IV) and the structured clinical interview for DSM-IV (SCID-IV). Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:1231–7.

Hasin D, Samet S, Nunes E, Meydan J, Matseoane K, Waxman R. Diagnosis of comorbid psychiatric disorders in substance users assessed with the psychiatric research interview for substance and mental disorders for DSM-IV. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:689–96.

Morgello S, Holzer CE, Ryan E, et al. Interrater reliability of the psychiatric research interview for substance and mental disorders in an HIV-infected cohort: experience of the national NeuroAIDS tissue consortium. Int J Methods Psych Res. 2006;15:131–8.

Hasin DS, Trautman KD, Endicott J. Psychiatric research interview for substance and mental disorders: phenomenologically based diagnosis in patients who abuse alcohol or drugs. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1998;34:3–8.

Gutierrez-Zotes JA, Bayon C, Montserrat C, et al. Temperament and character inventory revised (TCI-R) standardization and normative data in a general population sample. Actas espanolas psiquiatria. 2004;32:8–15.

Hegarty KL, Sheehan M, Schonfeld CA. Multidimensional definition of partner abuse: development and preliminary validation of the composite abuse scale. J Fam Violence. 1999;14:399–414.

Hegarty K, Bush R, Sheehan M. The composite abuse scale: further development and assessment of reliability in two clinical settings. Violence Vict. 2005;20:529–47.

Rathus SA. A 30-item schedule for assessing assertive behavior. Behav Ther. 1973;4:398–406.

Norton R, Warnick B. Assertiveness as a communication construct. Hum Comm Res. 1976;3:62–6.

Pearson JC. A factor analytic study of the items in the Rathus assertiveness schedule and the personal report of communication apprehension. Psychol Rep. 1979;45:491–7.

Rathus SA. An experimental investigation of assertive training in a group setting. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 1972;3:81–6.

Morokoff PJ, Quina K, Harlow LL, et al. Sexual assertiveness scale (SAS) for women: development and validation. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1997;73:790–804.

Darke S, Hall W, Heather N, Ward J, Wodak A. The reliability and validity of a scale to measure HIV risk-taking among intravenous drug users. AIDS. 1991;5:181–5.

SPSS Inc. Statistical Program for the Social Sciences. Chicago: SPSS; 2003.

QSR International Pty Ltd. NVivo qualitative data analysis software. Version 8; 2008.

Pope C, Ziebland S, Mays N. Qualitative research in health care: analysing qualitative data. BMJ. 2000;320:114–6.

Zahari MM, Hwan Bae W, Zainal NZ, Habil H, Kamarulzaman A, Altice FL. Psychiatric and substance abuse comorbidity among HIV seropositive and HIV seronegative prisoners in Malaysia. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2010;36:31–8.

Gilchrist G, Atkinson J, Gruer L. Illicit tranquilliser use and dependence among female opiate users. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2006;25:459–61.

Gilchrist G, Gruer L, Atkinson J. Predictors of neurotic symptom severity among female drug users in Glasgow, Scotland. Drugs Educ Prev Pol. 2007;14:347–65.

Brooner RK, Greenfield L, Schmidt CW, Bigelow GE. Antisocial personality disorder and HIV infection among intravenous drug abusers. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150:53–8.

Kelley JL, Petry NM. HIV risk behaviors in male substance abusers with and without antisocial personality disorder. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2000;19:59–66.

Ladd GT, Petry NM. Antisocial personality in treatment-seeking cocaine abusers: psychosocial functioning and HIV risk. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2003;24:323–30.

Petry NM. Discounting of delayed rewards in substance abusers: relationship to antisocial personality disorder. Psychopharmacol. 2002;162:425–32.

Fassino S, Dagaa GA, Delsedimea N, Rognaa L, Boggio S. Quality of life and personality disorders in heroin abusers. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004;76:73–80.

Hearn KD, O’Sullivan LF, El-Bassel N, Gilbert L. Intimate partner violence and monogamy among women in methadone treatment. AIDS Behav. 2005;9:177–86.

Montgomery SB, Hyde J, De Rosa CJ, et al. Gender differences in HIV risk behaviors among young injectors and their social network members. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2002;28:453–75.

Spittal PM, Craib KJP, Wood E, et al. Risk factors for elevated HIV incidence rates among female injection drug users in Vancouver. CMAJ. 2002;166:894–9.

MacRae R, Aalto E. Gendered power dynamics and HIV risk in drug-using sexual relationships. AIDS Care. 2000;12:505–15.

Panchanadeswaran S, Frye V, Nandi V, Galea S, Vlahov D, Ompad D. Intimate partner violence and consistent condom use among drug-using heterosexual women in New York City. Women Health. 2010;50:107–24.

Mateu-Gelabert P, Treloar C, Agulló Calatayud V, et al. How can hepatitis C be prevented in the long term? Int J Drug Policy. 2007;18:338–40.

El Bassel N, Gilbert L, Wu E, Chang M, Fontdevila J. Perpetration of intimate partner violence among men in methadone treatment programs in New York City. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:1230–2.

Copenhaver MM, Johnson BT, Lee IC, Harman JJ, Carey MP, SHARP Research Team. Behavioral HIV risk reduction among people who inject drugs: meta-analytic evidence of efficacy. J Sub Abuse Treat. 2006;31:163–71.

Hien DA, Campbell AN, Killeen T, et al. The impact of trauma-focused group therapy upon HIV sexual risk behaviors in the NIDA clinical trials network “Women and trauma” multi-site study. AIDS Behav. 2010;14:421–30.

Gilbert L, El-Bassel N, Terlikbayeva A, et al. Couple-based HIV prevention for injecting drug users in Kazakhstan: a pilot intervention study. J Prev Interv Community. 2010;38:162–76.

El-Bassel N, Terlikbaeva A, Pinkham S. HIV and women who use drugs: double neglect, double risk. Lancet. 2010;376:312–3.

Rounsaville B, Kleber H. Untreated opiate addicts: how do they differ from those seeking treatment? Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1985;42:1072–7.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by The Foundation for AIDS Research (amfAR) (fellowship grant #106953-43-RFAT), RD06/0001/1009 and FIS PI 07/0342. We would like to thank the staff and patients from CAS Barceloneta, CAS Extracta La Mina, CAS Sants, CAS Garbivent, Hospital del Mar Inpatient Detoxification Unit, Hospital Universitari Germans Trias i Pujol Inpatient Detoxification Unit, Dual Diagnosis Unit Centre Forum-Hospital del Mar and Juanse Hernández from the HIV treatments working group for their participation in the study. We are especially grateful to Joan Mestre, Francina Fonseca, Laura Diaz, Diana Martinez and Clara Perez for assisting with data collection.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gilchrist, G., Blazquez, A. & Torrens, M. Psychiatric, Behavioural and Social Risk Factors for HIV Infection Among Female Drug Users. AIDS Behav 15, 1834–1843 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-011-9991-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-011-9991-1