Abstract

We assessed the relationship between stress, substance use and sexual risk behaviors in a primary care population in Cape Town, South Africa. A random sample of participants (and over-sampled 18–24-year-olds) from 14 of the 49 clinics in Cape Town’s public health sector using stratified random sampling (n = 2,618), was selected. We evaluated current hazardous drug and alcohol use and three domains of stressors (Personal Threats, Lacking Basic Needs, and Interpersonal Problems). Several personal threat stressors and an interpersonal problem stressor were related to sexual risk behaviors. With stressors included in the model, hazardous alcohol use, but not hazardous drug use, was related to higher rates of sexual risk behaviors. Our findings suggest a positive screening for hazardous alcohol use should alert providers about possible sexual risk behaviors and vice versa. Additionally, it is important to address a broad scope of social problems and incorporate stress and substance use in HIV prevention campaigns.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

There is evidence that exposure to stressful events and circumstances (i.e., stressors) increases the risk of HIV infection (Ewart and Suchday 2002; Kalichman et al. 2005, 2006b; Latkin et al. 2005). Also, there is a positive association between substance use and sexual risk behavior (Campbell and Mzaidume 2002; Mnyika et al. 1997; Mpofu et al. 2006; Myer et al. 2002; Palen et al. 2006). However, few studies have investigated the effect of stressors and substance use on sexual risk behaviors simultaneously (Kalichman et al. 2005, 2006b). In this study we examine the independent relationship between stressors, hazardous substance use and sexual risk behaviors in a population-based sample of individuals seeking primary care in public sector outpatient clinics in Cape Town, South Africa.

Stressors and Sexual Risk Behaviors

Prior research suggests that stressors resulting from neighborhood events and conditions may play an integral role in exacerbating disease processes and undermining health (Ewart and Suchday 2002) including HIV infection (Kalichman et al. 2005, 2006b; Latkin et al. 2005). For example, Ewart and Suchday (2002) found that neighborhood disorder such as drug dealing in close proximity, the presence of drunken strangers near the home and gang fights as well as exposure to violence (whether the violence is inflicted on oneself by someone else or inflicted on a close friend or family member) has direct adverse effects on health outcomes. Latkin et al. (2005) found a direct connection between community stressors (such as neighborhood social disorder, violence, crime, loitering) and psychological distress. Psychological distress in turn was related to behavioral risk factors for HIV transmission. In addition, Wong et al. (2008) reported a relationship between exposure to community violence and sexual risk behavior. Kalichman et al. (2005, 2006b) examined the relationship between stress and sexual risk behaviors in South Africa. Specifically they assessed two domains of stressors; poverty-related stressors and personal threats. While they did not find a direct association between personal threat stressors and sexual risk behaviors, a significant association was found between poverty-related stressors and more risky behaviors. The empirical evidence linking stress and poor health (Kalichman et al. 2005, 2006b; Latkin et al. 2005), as well as the high morbidity and mortality rates in South Africa, underscore the need for further studies that examine the relationship between stress and sexual risk behaviors (Kalichman et al. 2005, 2006b).

The potential impact of the effect of relationship problems and health problems on sexual risk behavior in South Africa has not been studied. To our knowledge only one study among US high school students evaluated the relationship of physical disability and/or chronic disease to sexual risk behaviors (Jones and Lollar 2008). However, research on social support has linked the absence of social ties to family and friends as well as a lack of community involvement to premature death, regardless of one’s initial health (Berkman and Syme 1979; House et al. 1982). Within poorer communities which may be faced with unemployment, poor housing and other poverty-related stressors, the effects of one’s own or a loved one’s ill health may exacerbate stress (Sarason et al. 1985). In addition, teenage pregnancy rates in South Africa have increased in recent years (Dorrington et al. 2006). Unplanned pregnancies are also stressors, as they increase demands on households for food and other resources, and may interfere with the parents’ ability to work or study. Interpersonal problems also likely result in psychosocial stress which in turn may play an integral role in HIV infection by increasing sexual risk behavior.

Substance Use and Sexual Risk Behaviors

It is well-established that substance use is related to sexual risk behavior in some of Africa’s nations (Campbell and Mzaidume 2002; Mnyika et al. 1997; Myer et al. 2002). In South Africa, at the same time rates of HIV/AIDS are of great concern, rates of alcohol consumption are rising (Parry et al. 2004a) and the prevalence of problematic substance use among public sector primary care patients exceeds 10% (Ward et al. 2008). Thus, understanding the relationship between alcohol consumption and sexual risk behavior in South Africa is highly important (Kalichman et al. 2003, 2006a, b, 2005; Morojele et al. 2006; Simbayi et al. 2004; Smit et al. 2006). While some of the recent studies have used validated substance use screening measures such as the Alcohol, Smoking, and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST) or Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT) (Kalichman et al. 2006a; Simbayi et al. 2004; Smit et al. 2006) others have not (Kalichman et al. 2005, 2006b). One study conducted in a community-based South African sample (Smit et al. 2006) assessed alcohol problems using the AUDIT and found a significant association between problematic alcohol use and having sex while using alcohol or drugs. Two other studies assessing alcohol use with a validated measure were conducted in South African specialty populations. For example, Simbayi et al. (2004) and Kalichman et al. (2006a) used the AUDIT to measure problematic alcohol use and found a significant relationship between problem drinking and sexual risk behaviors among a sample of men and women seeking services from sexually transmitted infection (STI) clinics in South Africa.

The two remaining studies evaluated any lifetime use of alcohol consumption in a sample of participants from three Cape Town communities (Kalichman et al. 2005, 2006b). While both studies found significant relationships between alcohol use and multiple sexual risk behaviors, alcohol use was defined as ever drinking alcohol in one’s lifetime compared to never drinking alcohol. Findings from these studies underscore the need for research elucidating the role of current problematic alcohol use in relation to risky behavior as such knowledge has important implications for HIV and other STI interventions.

In addition to alcohol, illicit substance use is on the rise in South Africa. In particular, methamphetamine use is rapidly increasing and has become the main drug of abuse reported at treatment centers in the Western Cape (Morris and Parry 2006). Studies targeting South African adolescents have found a relationship between illicit substance use and sexual risk behaviors. For example, in studies of contraceptive non-use among sexually active high school students, inhalants increased the risk of unprotected sex (Flisher and Chalton 2001). Similarly, studies conducted outside South Africa found a link between illicit drug linked and condom non-use (Biglan et al. 1990; Hingson et al. 1990; Shrier et al. 1997) and multiple sexual behaviors (Ammon et al. 2005). Thus measuring problematic drug use as well as alcohol use in relation to sexual behavior is crucial.

Conceptual Model

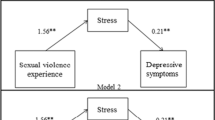

This study adapts a conceptual model by Kalichman et al. (2006b) evaluating stressors and substance use in relation to sexual risk behaviors . Their model suggests that sexual risk behaviors are influenced by stressors resulting from a lack of basic needs and personal threats. We adapt this to include a third domain of stressors, i.e., interpersonal problems, which prior research has found to be important stressors which may affect health problems (Sarason et al. 1985). Importantly, to our knowledge this study is the first South African study to use a validated measure of current (past 3 month) hazardous substance use (WHO ASSIST Working Group 2002) within this conceptual framework. Further it uses a population-based sample of public sector patients seeking primary health care, an important setting for providing screening and intervention. We hypothesize that poverty-related stressors, personal threat stressors and interpersonal problem stressors will be related to higher rates of risky behaviors. We also hypothesize that those who screen positive for problematic substance use will have a higher rate of sexual risk behaviors compared to those who do not.

Methods

Study Site and Procedures

The study employed a multi-stage cluster, stratified sampling design. Consistent with other South African research, we stratified the 49 Community Health Centers (CHCs) providing primary care in Cape Town by race as defined under apartheid, because of the continuing association with health disparities and substance use (Mager 2004; McIntyre and Gilson 2000). Proportions of race groups served at each clinic were estimated by the nursing and reception staff, because demographic characteristics such as race are not recorded by the CHCs. Stratification was based on clinics serving populations in which 80% or more were Colored; 80% or more were Black; and those serving more equal proportions of each racial group. Fourteen clinics were randomly selected proportional to the annual number of visits: six from the larger Colored stratum and four from each of the other two strata. Patients aged 18–24 were over-sampled as they visit the clinic less frequently and are found to be at higher risk. A total of 6,135 patients were sampled, and 2,618 (43% response rate) were interviewed. The reasons selected patients were not interviewed are as follows: the patient had already been seen by the doctor and left the clinic by the time the interviewer sought them (n = 2,688, 76%), the interviewer with the necessary gender or language match was absent that day (n = 293, 7%), the patient did not speak 1 of the 3 languages included in the study (n = 136, 4%), the patient was too ill to be interviewed (n = 58, 2%), interviewer believed the patient was too cognitively impaired to consent (n = 30, <1%), the patient was accompanied by a child and did not want to be interviewed in the child’s presence (n = 8, <1%), the patient refused (n = 142, 4%). These non-response rates appear to be primarily related to practical arrangements within the clinics, such as aspects of patient flow through the clinic and waiting times, and are unlikely to reflect systematic bias in terms of the variables of interest (Ward et al. 2008).

Sample

A total of 2,618 patients (1,128 men, 1,490 women) were recruited as they waited for their medical visit. The weighted sample consisted of a majority of Black participants (60%), followed by Colored (39%), with few Whites (1%) or Indians (<1%). Only 9% was less than 25 years old, nearly half were married (45%), and 10% had less than a high school education. (For more information on the construction of the weights, see Data Analysis Section). Less than a third of the sample was employed (30%) and 44% reported the head of the household was unemployed. Twenty-two percent of the participants lived in informal housing, 9% reported they did not have electricity, and 6% did not have access to piped water. Most participants were interviewed in Xhosa (58%), 38% were interviewed in Afrikaans, and 24% in English.

Measures

The questionnaire was developed in English, translated into Afrikaans and Xhosa and checked through back-translation into English.

Demographic Characteristics

Demographic data collected included age (18–24 vs. ≥25 years), race (black vs. colored/other) and gender.

Sexual Risk Behavior

The sexual risk behavior variable included a count of the number of risk behaviors out of six. Five of the risk behaviors were related to practices within the past year; had a partner who ever traded sex for drugs, transportation, or money (including with respondent), had a partner who was a man who has ever had sex with a man, had a partner who used injection drugs, had a partner who had an STI, or had multiple partners (2+). The final risk behavior was failure to use a condom at last intercourse.

Hazardous Substance Use

We used the ASSIST (Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test) (WHO ASSIST Working Group 2002) to assess hazardous alcohol and drug use. It is a validated brief screening questionnaire designed for use by primary health care workers in a range of health care settings to screen for hazardous or harmful use of alcohol, tobacco, and illicit drugs. The ASSIST asks six questions for alcohol and each type of drug and tobacco, including frequency of use, having a “strong desire or urge” to use, having had legal, financial, social, or health consequences of use, failure to do what was normally expected because of use, having someone express concern about use, and having failed to cut down or stop using. Possible ASSIST scores for alcohol and each drug range from 0 to 33.

We adapted the ASSIST to local conditions in two ways (Ward et al. 2008). Methaqualone was added to the list of drugs due to its high frequency of use in South Africa. In addition, local drug names for both cannabis (dagga) and methaqualone (Mandrax) were included. As per the WHO ASSIST scoring instructions, specific scores were calculated for each substance where use was reported in the prior three months. These can be categorized as low- (including zero), medium- and high-risk use. Medium risk indicates problematic use, while high risk indicates high probability of dependence (Henry-Edwards et al. 2003). We dichotomized the risk category at the threshold of hazardous risk so that medium and high risk were coded “1” and low and no risk was coded “0.” The instrument has high reliability (Newcombe et al. 2005; WHO ASSIST Working Group 2002).

Stressors

We considered three domains of stressors: lacking basic needs, personal threats and interpersonal problems. The stressor questions were taken from the International Classification of Primary Care, Second Edition (ICPC-2) (World Health Organization 1998), with the addition of one question which asked about unplanned pregnancies. The ICPC-2 lists 23 stressors that may be reasons for seeking health care. Rates of births to teenagers are very high in South Africa, can be a considerable family stressor and are associated with increased risk for HIV infection (Bradshaw et al. 2004; Smit et al. 2004), but are not addressed in the ICPC-2. The stressors included in the three domains are described in the following respective sections.

Lacking Basic Needs

Of the six stressors in the lacking basic needs domain, two were taken from the ICPC-2 and addressed occurrences within the prior 12 months, while four addressed the respondents’ current living circumstances. The two questions from the ICPC-2 asked whether the respondent had problems getting food or water, and whether they had lost their home. The other four lacking basic needs items included: no piped water at home, no electricity for lighting at home, the head of the household is not employed, and respondent lives in a shack, wendy house/backyard dwelling, tent or other traditional dwelling, as opposed to a house or flat. These are items from the South African census and correlate with health-related deprivation in urban areas (McIntyre et al. 2002).

Personal Threats

Four items taken from the ICPC-2 comprise the personal threats domain. These pertain to experiences in the past year and include: been in a situation in which you were seriously injured, had legal problems or problems with the police, lost your job/been unemployed/had problems with your pension, had important things stolen from you. The grouping was based on a prior study which combined similar stressors from a different instrument into one domain (Kalichman et al. 2006b).

Interpersonal Problems

The interpersonal problems domain consists of two categories of stressors, and a separate item taken from the ICPC-2, as well as one question added based upon previous research (Ward et al. 2008). The first category deals with having lost or having an ill family member and includes a positive response to any of the following: (1) lost your partner, your partner died or left, or you divorced, (2) lost your child, (3) lost a parent or other family member (not your child or partner), (4) had problems with partner being ill, (5) had problems with child being ill, (6) had problems with an illness in a parent or another family member (not your partner or child). The second category, relationship problems, consists of stating “yes” to any of the following six: (1) had problems in your relationship with your partner (husband, wife, boyfriend, or girlfriend), (2) had problems in your relationship with your child, (3) had problems in your relationship with your parents or another family member (not your child or partner), (4) had problems in a relationship with a friend or with others (not your family), (5) had problems in your relationship with your neighbors, (6) had problems with your co-workers or supervisors at work. Suffering from bad health, was the third possible interpersonal problem stressor. The fourth item was added to the questionnaire by the study team, “Have you or anyone else in your household had an unplanned pregnancy?” As discussed above, this was included because rates of teenage pregnancies are very high in South Africa (Dorrington et al. 2006) and are often a reason for a primary care visit.

Data Analysis

Weights were constructed to adjust for the over-quota of 18–24-year-olds, differential non-response rates (by gender, age, and race) within clinics, the size of the clinics proportion to the full population served by Cape Town’s Community Health Centers and the stratified sampling design. Weights ranged from 0.02 to 12.1 (median = 0.34; interquartile range = 0.14–0.72). All analyses were weighted accounting for the study’s multi-stage, clustered, stratified design. Pearson’s Chi-square [corrected for survey design using the second-order correction of Rao and Scott (1984) and converted into an F statistic] was used to evaluate categorical data. The distribution of the dependent variable (number of sexual risk behaviors) followed a Poisson distribution. A Poisson model was fit first, but due to overdispersion (extra-Poisson variation) the negative binomial model was found to be a better fit (Hilbe 2007). Therefore, a negative binomial regression model was conducted to model the association between stressors, hazardous substance use and the number of sexual risk behaviors while adusting for age, gender and race. To determine which predictor variables to include in the final model we conducted bivariate analyses with each predictor (demographic characteristics, stressors, hazardous substance use) and the dependent variable, sexual risk behaviors. Significant predictors (P < 0.05) were considered in multivariable analyses. To assess the relationship between stressors and demographic characteristics without hazardous substance use we first fit a model with all significant demographic characteristics and stressors. The final model included all demographic characteristics, stressors and hazardous substance use measures significantly associated with sexual risk behavior in the bivariate models. The measure of effect is an incidence rate ratio (IRR).

Results

Twenty-six percent of the participants reported a minimum of 1 sexual risk behavior (Table 1). Of all participants, 20% reported one sexual risk behavior, 5% reported 2 risk behaviors, and <1% reported each of 3, 4, 5, and 6 sexual risk behaviors. The two most prevalent sexual risk behaviors were having multiple sex partners in the last year (14.8%) and not using a condom at last intercourse (12.6%) (Table 2).

Younger age, gender and race were each significantly associated with one or more sexual risk behaviors. Forty-four percent of the 18–24 year olds reported at least one sexual risk behavior compared to only 25% of the older participants (P < 0.001). Males (39%) compared to females (19%) were more likely to report sexual risk behaviors.

Several personal threats stressors were related to engaging in sexual risk behavior. Participants with legal problems, as well as those who were victims of a serious injury (Injury) or those who had important things stolen from them (Crime) were significantly more likely to report engaging in sexual risk behaviors (Table 1). Only one lacking basic needs stressor was significantly associated with sexual risk behavior. Participants who lived in a house in which the head of the household was unemployed were less likely to engage in risky behaviors compared to participants living in households in which the head was employed (P < 0.05). Stress resulting from relationship problems was the only interpersonal problems stressor related to risky sexual behavior. Participants with relationship problems (35%) were more likely to report sexual risk behavior compared to participants without relationship problems (21%; P < 0.01). Finally, hazardous alcohol users (52 vs. 22%; P < 0.001) and hazardous drug users (53 vs. 25%; P < 0.001) were more likely to engage in sexual risk behaviors compared to non-hazardous substance users.

Among the personal threat stressors, losing one’s job or pension was not significantly related to any sexual risk behaviors (Table 2). However, victims of a serious injury and participants who had important things stolen from them were more likely to engage in five of the six risk behaviors, having a partner who ever traded sex for drugs or money, having a partner who used injection drugs, having a partner who was a man who has had sex with another man, having a partner who had an STI and not using a condom during last sexual intercourse (P < 0.05 for all).

Very few significant differences were found between the lacking basic needs stressors and the individual sexual risk behaviors (Table 2). Participants living in a situation in which the head of the household was unemployed were less likely to report having sex with a partner who has had an STI, having multiple sex partners and not using a condom at last sexual intercourse (P < 0.05 for all).

Each of the four interpersonal problems stressors was significantly related to one sexual risk behavior. For example, participants with relationship problems were less likely to use a condom at last intercourse compared to participants without relationship problems (P < 0.05).

Hazardous alcohol use was significantly related to all sexual risk behaviors with the exception of a partner who has ever had sex with a man (P < 0.05). Hazardous drug use was not significantly associated with using a condom at last intercourse, but was significantly related to all other sexual risk behaviors (P < 0.05).

Table 3 shows the negative binomial regression models examining the relationship between demographic characteristics, stressors, hazardous substance use and sexual risk behaviors. The column of table three titled, “unadjusted models” displays the bivariate results for each specific predictor and the dependent variable, sexual risk behaviors. For example, in a model with only hazardous alcohol use predicting sexual risk behaviors, hazardous alcohol use was significantly associated with a higher rate of sexual risk behaviors. All significant predictors were included in Model 1 and/or Model 2.

The first multivariable model (Table 3; Model 1) included all significant predictors of sexual risk behaviors with the exception of the two hazardous substance use variables. The results suggest that younger participants and males had a higher rate of sexual risk behaviors compared to older participants and females (IRR: 1.6, 2.7, respectively; P < 0.05). Blacks were less likely to engage in sexual risk behaviors compared to others (IRR: 0.7; P < 0.05). After adjusting for demographic characteristics, two personal threats stressors remained significantly associated with sexual risk behaviors. Participants with legal problems had a higher rate of sexual risk behavior compared to participants without legal problems (IRR: 1.3; P < 0.05). In addition, victims of a serious injury were more likely to report sexual risk behaviors compared to participants who had not suffered a serious injury (IRR: 1.5; P-value < 0.05). Living in a situation in which the head of the household was not employed was the only lacking basic needs stressor significantly related to sexual risk behavior (IRR: 0.7; P < 0.05). Participants who reported relationship problems had a higher rate of sexual risk behaviors (IRR: 1.5; P < 0.05). Relationship problems were the only interpersonal problem stressors significantly related to sexual risk behavior.

Inclusion of hazardous substance use in the model affected the significance of one personal threats stressor (suffering from an injury) and the single lacking basic needs stressor (head of household not employed) (Table 3; Model 2). However, the IRRs remained predominately the same for all demographic characteristics and other stressors. Controlling for other variables in the model, hazardous alcohol users had a higher rate of sexual risk behavior compared to non-hazardous alcohol users (IRR: 1.5; P < 0.05). Hazardous drug use was not significantly related to sexual risk behavior in the multivariable model.

Discussion

Our results suggest that both stressors and hazardous substance use have independent relationships with sexual risk behaviors. We found strong relationships between several personal threat stressors and risky sexual behavior even after hazardous alcohol use was considered. In addition, several demographic characteristics were significant predictors of sexual risk behaviors.

The relationship between several personal threat stressors and sexual risk behavior did not diminish after including hazardous alcohol use and hazardous drug use in the model. These findings demonstrate the robust relationship between these stressors and sexual risk behaviors. Our findings are contrary to previous research which did not find a direct relationship between such stressors and HIV risk behavior (Kalichman et al. 2005, 2007). The discrepancy may be a result of differing methods to evaluate personal threat stressors. For example, our study evaluated whether the participant experienced each individual personal threat stressor, whereas Kalichman et al. (2007) assessed the perceived degree of a problem the stressor was and then evaluated personal threat stressors as a scale. In addition, our study used different instruments to assess the various stressors.

We did not find a significant link between a lack of basic needs and sexual risk behaviors, both contradicting and supporting previous research. In one study, Kalichman et al. (2005) reported a significant direct relationship. However, another study from a township and surrounding settlements, reported a direct relationship between a lack of basic needs for Africans, but not for Colored participants (Kalichman et al. 2005). The current study did not find a significant association when hazardous alcohol use and hazardous drug use were included. This discrepancy may be due to the sampling differences between the studies. Our study was based in public settings. It included a sample of all public primary health clinics in Cape Town, increasing the likelihood of a more homogenously lower socio-economic-status population. In Kalichman’s study, participants were recruited from three different socio-demographic areas (Kalichman et al. 2006b). Our lack of a significant finding may be an artifact of little to no variance in our population with regard to the lacking basic needs stressor domain. Further research needs to be conducted on a lack of basic necessities and how such a stressor may relate to sexual risk behaviors for HIV and other sexually transmitted infections.

Adding to the literature we found a significant relationship between one interpersonal problem stressor and engaging in sexual risk behavior. Experiencing relationship problems is related to higher rates of sexual risk behaviors. Further research using qualitative and longitudinal quantitative methods could illuminate the direction of this relationship, which this cross-sectional study cannot do.

In this sample of primary health care patients in Cape Town, South Africa, hazardous alcohol use was strongly related to sexual risk behavior. Not only were hazardous alcohol users engaging in a greater number of risky behaviors, but they were also more likely not to use a condom at last sexual intercourse. These findings are similar to previous research on alcohol use and sexual risk behaviors in South Africa (Flisher and Chalton 2001; Flisher et al. 2000; Kalichman et al. 2005, 2006b; Mpofu et al. 2006; Palen et al. 2006).

In our study, hazardous drug use was not related to sexual risk behavior when controlling for hazardous alcohol use. When hazardous alcohol use was excluded from the multivariable model, the relationship between hazardous drug use and sexual risk behavior remained unchanged, and not significantly associated with higher rates of sexual risk behaviors. These results contradict previous findings which have found a significant association between drug use and sexual risk behaviors in South Africa (Kalichman et al. 2006b; Simbayi et al. 2006). A possible explanation for these contrary findings is the use of different instruments and time frames for assessing drug use. For example, in the Kalichman et al. (2006b) study, drug use corresponded to any lifetime drug use, whereas our study evaluated current hazardous drug use. While Simbayi et al. (2006) found an association between methamphetamine use and risky sexual behaviors, they compared methamphetamine users to other non-methamphetamine drug users. A second possible explanation is that the most prevalent drug in the current study was marijuana at the time this study was conducted. Marijuana may have less dramatic effects on behavior than “harder” drugs such as methamphetamines, which are now becoming highly prevalent in South Africa (Volkow et al. 2007).

As previously reported (Ward et al. 2008), slightly more than one-fifth of our sample screened positive for hazardous substance use during a period in which reports indicate an increase in alcohol consumption in South Africa (Parry et al. 2004a). Our results not only show a significant relationship between hazardous substance use and sexual risk behaviors, but they also suggest the possible consequences that an increase in substance use may have on the HIV epidemic. Screening and interventions for hazardous substance use in public sector primary care clinics may also reduce sexual risk behaviors linked to HIV and other STIs, and this population may be an important target for HIV interventions.

Limitations

Our findings should be interpreted within the study’s limitations. First, these data are based on self-report and are thus subject to the limitations of self-report bias. For example, the prevalence of hazardous substance use is subject to biases such as problems recalling drug use and social desirability of responses (Johnson and Fendrich 2005). However, the ASSIST has been found to be reliable and acceptable for screening use internationally (WHO ASSIST Working Group 2002), and to have validity similar to other established self-report instruments (Newcombe et al. 2005). Due to the timing of the study, the more recent epidemic in methamphetamine use (Parry et al. 2004b) is not reflected in our data. We also missed a large number of patients. However, this was most likely caused by factors related to the clinics’ ability to process patients, and not to the variables under study, and so is unlikely to have introduced any systematic bias. Finally, this study is a cross-sectional design. Therefore, all findings can only be interpreted as associations and we cannot draw causal inferences. Future longitudinal studies should be conducted to establish causal associations between stressors, hazardous substance use and sexual risk behaviors.

Conclusion

Our study has important implications for targeted HIV prevention efforts. Our findings suggest that a patient who screens positive for hazardous alcohol use should also be screened for sexual risk behaviors and vice versa. Additionally, our findings accentuate the importance of addressing the broader scope of social problems and incorporating societal factors in HIV prevention campaigns.

References

Ammon, L., Sterling, S., Mertens, J., & Weisner, C. (2005). Adolescents in private chemical dependency programs: Who are most at risk for HIV? Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 29, 39–45. doi:10.1016/j.jsat.2005.03.003.

Berkman, L. F., & Syme, S. L. (1979). Social networks, host resistance, and mortality: a nine-year follow-up study of Alameda County residents. American Journal of Epidemiology, 109, 186–204.

Biglan, A., Metzler, C. W., Wirt, R., Ary, D., Noell, J., Ochs, L., et al. (1990). Social and behavioral factors associated with high-risk sexual behavior among adolescents. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 13, 245–261. doi:10.1007/BF00846833.

Bradshaw, D., Pettifor, A., MacPhail, C., & Dorrington, R. (2004). Trends in youth risk for HIV. In P. Ijumba, C. Day, & A. Ntuli (Eds.), South African health review 2003/2004 (pp. 136–145). Durban: Health Systems Trust.

Campbell, C., & Mzaidume, Y. (2002). How can HIV be prevented in South Africa? A social perspective. British Medical Journal, 324, 229–232. doi:10.1136/bmj.324.7331.229.

Dorrington, R. E., Johnson, L. F., Bradshaw, D., & Daniel, T. (2006). The demographic impact of HIV/AIDS in South Africa. National and provincial indicators for 2006. Cape Town: Center for Actuarial Research, South African Medical Research Council and Actuarial Society of South Africa.

Ewart, C. K., & Suchday, S. (2002). Discovering how urban poverty and violence affect health: Development and validation of a Neighborhood Stress Index. Health Psychology, 21, 254–262. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.21.3.254.

Flisher, A. J., & Chalton, D. O. (2001). Adolescent contraceptive non-use and covariation among risk behaviors. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 28, 235–241. doi:10.1016/S1054-139X(00)00157-9.

Flisher, A. J., Kramer, R. A., Hoven, C. W., King, R. A., Bird, H. R., Davies, M., et al. (2000). Risk behavior in a community sample of children and adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 39, 881–887. doi:10.1097/00004583-200007000-00017.

Henry-Edwards, S., Humeniuk, R., Ali, R., Poznyak, V., & Monteiro, M. (2003). The alcohol, smoking and substance involvement screening test (ASSIST): Guidelines for use in primary care (Version 5). Geneva: World Health Organization.

Hilbe, J. M. (2007). Negative binomial regression. Cambridge: Cambridge University.

Hingson, R. W., Strunin, L., Berlin, B. M., & Heeren, T. (1990). Beliefs about AIDS, use of alcohol and drugs, and unprotected sex among Massachusetts adolescents. American Journal of Public Health, 80, 295–299. doi:10.2105/AJPH.80.3.295.

House, J. S., Robbins, C., & Metzner, H. L. (1982). The association of social relationships and activities with mortality: Prospective evidence from the Tecumseh Community Health Study. American Journal of Epidemiology, 116, 123–140.

Johnson, T., & Fendrich, M. (2005). Modeling sources of self-report bias in a survey of drug use epidemiology. Annals of Epidemiology, 15, 381–389. doi:10.1016/j.annepidem.2004.09.004.

Jones, S. E., & Lollar, D. J. (2008). Between physical disabilities or long-term health problems and health risk behaviors or conditions among us high school students. The Journal of School Health, 78, 252–257. doi:10.1111/j.1746-1561.2008.00297.x.

Kalichman, S. C., Cain, D., Zweben, A., & Swain, G. (2003). Sensation seeking, alcohol use and sexual risk behaviors among men receiving services at a clinic for sexually transmitted infections. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 64, 564–569.

Kalichman, S. C., Simbayi, L. C., Cain, D., & Jooste, S. (2007). Alcohol expectancies and risky drinking among men and women at high-risk for HIV infection in Cape Town, South Africa. Addictive Behaviors, 32, 2304–2310. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.01.026.

Kalichman, S. C., Simbayi, L. C., Jooste, S., Cain, D., & Cherry, C. (2006a). Sensation seeking, alcohol use, and sexual behaviors among sexually transmitted infection clinic patients in Cape Town, South Africa. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 20, 298–304. doi:10.1037/0893-164X.20.3.298.

Kalichman, S. C., Simbayi, L. C., Jooste, S., Cherry, C., & Cain, D. (2005). Poverty-related stressors and HIV/AIDS transmission risks in two South African communities. Journal of Urban Health, 82, 237–249. doi:10.1093/jurban/jti048.

Kalichman, S. C., Simbayi, L. C., Kagee, A., Toefy, Y., Jooste, S., Cain, D., et al. (2006b). Associations of poverty, substance use, and HIV transmission risk behaviors in three South African communities. Social Science & Medicine, 62, 1641–1649. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.08.021.

Latkin, C. A., Williams, C. T., Wang, J., & Curry, A. D. (2005). Neighborhood social disorder as a determinant of drug injection behaviors: A structural equation modeling approach. Health Psychology, 24, 96–100. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.24.1.96.

Mager, A. (2004). ‘White liquor hits black livers’: Meanings of excessive liquor consumption in South Africa in the second half of the twentieth century. Social Science & Medicine, 59, 735–751. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.12.005.

McIntyre, D., & Gilson, L. (2000). Redressing dis-advantage: promoting vertical equity within South Africa. Health Care Analysis, 8, 235–258. doi:10.1023/A:1009483700049.

McIntyre, D., Muirhead, D., & Gilson, L. (2002). Geographic patterns of deprivation in South Africa: Informing health equity analyses and public resource allocation strategies. Health Policy and Planning, 17(1), 30–39. doi:10.1093/heapol/17.suppl_1.30.

Mnyika, K. S., Klepp, K. I., Kvale, G., & Ole-Kingori, N. (1997). Determinants of high-risk sexual behaviour and condom use among adults in the Arusha region, Tanzania. International Journal of STD & AIDS, 8, 176–183. doi:10.1258/0956462971919840.

Morojele, N. K., Kachieng’ab, M. A., Mokoko, E., Nkoko, M. A., Parry, C. D. H., Nkowane, A. M., et al. (2006). Alcohol use and sexual behaviour among risky drinkers and bar and shebeen patrons in Gauteng province, South Africa. Social Science & Medicine, 62, 217–227. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.05.031.

Morris, K., & Parry, C. (2006). South African methamphetamine boom could fuel further HIV. The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 6, 471. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(06)70539-4.

Mpofu, E., Flisher, A. J., Bility, K., Onya, H., & Lombard, C. (2006). Sexual partners in a rural South African setting. AIDS and Behavior, 10, 399–404. doi:10.1007/s10461-005-9037-7.

Myer, L., Mathews, C., & Little, F. (2002). Condom use and sexual behaviors among individuals procuring free male condoms in South Africa: A prospective study. Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 29, 239–241. doi:10.1097/00007435-200204000-00009.

Newcombe, D. A., Humeniuk, R. E., & Ali, R. (2005). Validation of the World Health Organization Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST): Report of results from the Australian site. Drug and Alcohol Review, 24, 217–226. doi:10.1080/09595230500170266.

Palen, L. A., Smith, E. A., Flisher, A. J., Caldwell, L. L., & Mpofu, E. (2006). Substance use and sexual risk behavior among South African eighth grade students. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 39, 761–763. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.04.016.

Parry, C. D., Myers, B., Morojele, N. K., Flisher, A. J., Bhana, A., Donson, H., et al. (2004a). Trends in adolescent alcohol and other drug use: Findings from three sentinel sites in South Africa (1997–2001). Journal of Adolescence, 27, 429–440. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2003.11.013.

Parry, C. D., Myers, B., & Pluddemann, A. (2004b). Drug policy for methamphetamine use urgently needed. South African Medical Journal, 94, 964–965.

Rao, J. N. K., & Scott, A. J. (1984). On chi-squared tests for multiway contingency-tables with cell proportions estimated from survey data. Annals of Statistics, 12, 46–60. doi:10.1214/aos/1176346391.

Sarason, I. G., Sarason, B. R., Potter, E. H., I. I. I., & Antoni, M. H. (1985). Life events, social support, and illness. Psychosomatic Medicine, 47, 156–163.

Shrier, L. A., Emans, S. J., Woods, E. R., & DuRant, R. H. (1997). The association of sexual risk behaviors and problem drug behaviors in high school students. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 20, 377–383. doi:10.1016/S1054-139X(96)00180-2.

Simbayi, L. C., Kalichman, S. C., Cain, D., Cherry, C., Henda, N., & Cloete, A. (2006). Methamphetamine use and sexual risks for HIV infection in Cape Town, South Africa. Journal of Substance Use, 11, 291–300. doi:10.1080/14659890600625767.

Simbayi, L. C., Kalichman, S. C., Jooste, S., Mathiti, V., Cain, D., & Cherry, C. (2004). Alcohol use and sexual risks for HIV infection among men and women receiving sexually transmitted infection clinic services in Cape Town, South Africa. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 65, 434–442.

Smit, J., Beksinska, M., Ramkissoon, A., Kunene, B., & Penn-Kekana, L. (2004). Reproductive health. In P. Ijumba, C. Day, & A. Ntuli (Eds.), South African review 2003/04 (pp. 59–81). Durban: Health Systems Trust.

Smit, J., Myer, L., Middelkoop, K., Seedat, S., Wood, R., Bekker, L. G., et al. (2006). Mental health and sexual risk behaviours in a South African township: A community-based cross-sectional study. Public Health, 120, 534–542. doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2006.01.009.

Volkow, N. D., Wang, G. J., Fowler, J. S., Telang, F., Jayne, M., & Wong, C. (2007). Stimulant-induced enhanced sexual desire as a potential contributing factor in HIV transmission. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 164, 157–160. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.164.1.157.

Ward, C. L., Mertens, J. R., Flisher, A. J., Bresick, G. F., Sterling, S. A., Little, F., et al. (2008). Prevalence and correlates of substance use among South african primary care clinic patients. Substance Use & Misuse, 43, 1395–1410. doi:10.1080/10826080801922744.

WHO ASSIST Working Group. (2002). The alcohol, smoking and substance involvement screening test (ASSIST): Development, reliability and feasibility. Addiction (Abingdon, England), 97, 1183–1194. doi:10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00185.x.

Wong, F. Y., Huang, Z. J., DiGangi, J. A., Thompson, E. E., & Smith, B. D. (2008). Gender differences in intimate partner violence on substance abuse, sexual risks, and depression among a sample of South Africans in Cape Town, South Africa. AIDS Education and Prevention, 20, 56–64. doi:10.1521/aeap.2008.20.1.56.

World Health Organization. (1998). International classification of primary care (ICPC-2) (2nd ed.). Geneva: World Health Organization.

Acknowledgments

We thank Agatha Hinman for editorial assistance, Jason Bond, PhD. for statistical support, and the fieldworkers, Beulah Marks, Bongu Maku, Morris Manuel, and Asanda Mabusela. We are also grateful to the patients who participated in this study. The US National Institute on Drug Abuse (through the Southern African Initiative) and the South African Medical Research Council provided study funding (grant R37 DA10572).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Avalos, L.A., Mertens, J.R., Ward, C.L. et al. Stress, Substance Use and Sexual Risk Behaviors Among Primary Care Patients in Cape Town, South Africa. AIDS Behav 14, 359–370 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-009-9525-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-009-9525-2