Abstract

As world food and fuel prices threaten expanding urban populations, there is greater need for the urban poor to have access and claims over how and where food is produced and distributed. This is especially the case in marginalized urban settings where high proportions of the population are food insecure. The global movement for food sovereignty has been one attempt to reclaim rights and participation in the food system and challenge corporate food regimes. However, given its origins from the peasant farmers' movement, La Via Campesina, food sovereignty is often considered a rural issue when increasingly its demands for fair food systems are urban in nature. Through interviews with scholars, urban food activists, non-governmental and grassroots organizations in Oakland and New Orleans in the United States of America, we examine the extent to which food sovereignty has become embedded as a concept, strategy and practice. We consider food sovereignty alongside other dominant US social movements such as food justice, and find that while many organizations do not use the language of food sovereignty explicitly, the motives behind urban food activism are similar across movements as local actors draw on elements of each in practice. Overall, however, because of the different histories, geographic contexts, and relations to state and capital, food justice and food sovereignty differ as strategies and approaches. We conclude that the US urban food sovereignty movement is limited by neoliberal structural contexts that dampen its approach and radical framework. Similarly, we see restrictions on urban food justice movements that are also operating within a broader framework of market neoliberalism. However, we find that food justice was reported as an approach more aligned with the socio-historical context in both cities, due to its origins in broader class and race struggles.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

New global challenges have arisen in feeding poor people in rapidly expanding urban areas. Cities currently hold more than half of the world’s population and in the next decade an estimated 3.5 billion people (FAO 2010) will seek wage labor and income in sprawling cities (Sassen 1990; Bello 2009). Confounding the challenge of food production for growing urban populations are the mounting pressures of high oil prices, climate change and greater competition for land and water. A mix of social, political and economic marginalization has further complicated the provision of urban food, making equitable access to food a challenging local priority. In this context, the challenge has not been growing enough food per se, but rather producing and distributing food in ways accessible and affordable for the growing urban poor (Weis 2007). Millions of poor people who reside in urban areas remain hungry due to their inability to pay for and/or access food through other means due to constraints in society and the modern food system (Patel 2007).

The 2007/8 and 2011 food price crises have highlighted the fragility and vulnerability of the food system to pressures such as the global financial crisis, food commodity speculation, climate change, changing consumption patterns, peak oil and the rise in biofuel production (Martine et al. 2008; Lagi et al. 2011; Clapp and Helleiner 2012; McMichael 2012). These factors have merged in a ‘perfect storm’ resulting in food price hikes and a new wave of hunger globally. In 2007 alone, the world’s hungry had increased by a further 75 million people resulting in over one billion under-nourished people globally (FAO 2008). Lang (2010) argues that food crises are becoming a normal condition as the twenty-first century productionist food paradigm loses momentum.

These complex global market forces manifest as social costs such as diminishing access to food (Sassen 1990). Whilst food price hikes are felt most abruptly in developing countries where food equates to a high proportion of overall living costs, people living in the economic margins of so-called wealthy nations are also severely affected. In the USA, the focus of this study, these effects are seen in urban areas, where a disproportionate number of poor African-Americans, Hispanics and other ethnic minorities live in (often) unsubsidized housing and depend on low-wage employment. Urban areas often have high food prices due to infrastructure and transportation costs, with most urban poor relying on staples such as rice and wheat, the very products that soared in cost in 2008 (Martine et al. 2008, p. 6). Whilst the effects of food price increases are felt most keenly in the Global South, the 2008 food spikes priced 50 million Americans out of the food market (Holt-Giménez and Patel 2009, p. 62). Some suggest that modern cities in the Global North are ‘food deserts’, places where junk food is more readily accessible than affordable fresh food (Holt-Giménez and Patel 2009; Burns 2014). As the number of urban poor has grown, so too has urban food insecurity in the US, with 15 % of city dwellers recently reported to be food insecure (Kirkpatrick and Tarasuk 2011). Where only 2 % of the US population still farm, and very few farm in cities, income and food security are highly correlated (Holt-Giménez and Patel 2009).

In response to growing food insecurity, urban food movements are on the rise, demanding greater access and equal rights to food in cities (Wittman 2011). These movements operate from various rights-based ideological standpoints, including food sovereignty and food justice. This paper examines urban food movements that are emerging in the US in response to insecure and limited access to food among the urban poor. Such movements tend to tap into alternative networks of food production, whether through backyard or community gardening, local markets, or community-supported agriculture (CSAs). Alternative food movements have different strategies and practices that aim to change conditions in urban settings, but share common visions of a more equitable food system (see Allen et al. 2003; Maye et al. 2007; McClintock 2008, 2014). Two key questions inform this study. First, to what extent have the pressures and constraints of the current corporate food system enabled a ‘food sovereignty’ approach to form in cities of the United States? Second, how does ‘food sovereignty’, given its origins from peasant farmer movements in the Global South, manifest and adapt to the context of poor, urban consumers in the Global North?

In order for the global food sovereignty movement to progress, the extent, significance and connection to urban food sovereignty movements, especially in the US, must be understood in a socio-political context. We do this by examining how NGOs, activists and urban farmers perceive ‘food sovereignty’ by situating struggles to overcome constraints in accessing affordable, healthy food. Investigating the extent to which US food movements relate to global food sovereignty movements is key: it highlights how politically radical food movements are (or are not) challenging the current, corporate food regime by exposing the strategies that work in the ‘in-between spaces’ of neoliberalism (Peck and Tickell 2002).

This study is based on key informant interviews and site visits with food system academics, as well as activists and farmers engaged in food movements in Oakland and New Orleans. We examine how and why US urban food activism unfolds, and what concepts, strategies and practices enable contestation of the dominant corporate food regime. The two cities were chosen because both share similar economic and social injustices, including poverty, violence and police brutality. Oakland has a history of urban food activism, while New Orleans is a relative newcomer to urban food movements, which were formed in response to the Hurricane Katrina disaster.

Using purposive, network sampling, thirty-two actors involved in US urban agriculture were interviewed. This included ten academic-activists and twenty-two people who had a high profile in the alternative food sector.Footnote 1 These were workers in NGOs, grass-roots activists, urban farmers and people involved in community organizations. The informants were selected because of their high level of involvement in alternative food movements in each city. To identify potential informants, key organizations active within Oakland and New Orleans’ food movement programs were asked to name the key agents involved in the food movement in their city. In many instances the same names were repeated, highlighting a core group of people heavily engaged in urban agriculture and alternative food economies. The interviewees were asked about the motives, ideologies and practices underpinning their work. The interviews were recorded and transcribed, and key words and phrases were grouped to examine and compare relationships and understandings of food justice and food sovereignty. The sections below expand upon the political economy of global food systems, situating the Oakland and New Orleans cases within an integrated, global food economy, and highlight the context within which food sovereignty movements have arisen.

Food regimes and capitalist agriculture

Despite on-going investments in technological fixes for big agriculture, global statistics show that a significant proportion of the world’s poor are not adequately fed, with the number of people in hunger expected to pass one billion (FAO 2010). Friedmann and McMichael (1989) suggest the inadequacies of the global food system have emerged through successive ‘food regimes’. They illustrate how growing capital and international trade has undercut developing economies, “reconstructing consumption relations as part of the process of capital accumulation—with particular consequences for agricultural production” (Friedmann and McMichael 1989, p. 95). They argue that three distinct food regimes are identifiable. From 1870 to 1914, the first food regime organized and specialized trade among European countries and ‘settler’ states across the hemispheres, where primary and processed resources (e.g., wheat and meat) were exported from the latter to the former. In return, settler states imported valuable manufactured goods, labor and capital from Europe, often facilitating resource extraction and agricultural production (Friedmann and McMichael 1989, p. 96).

The second food regime formed thirty years later, from the 1950s to the 1970s. The US became the main trade actor between post-colonial states, redirecting the flow of food from the South to North, with the transfer of agricultural surplus to developing countries (initially as food aid) (Holt-Giménez and Shattuck 2011). Post-colonial states saw their agricultural exports become more specialized and manufactured, destined for distant markets, while their imports were surplus wheat from (subsidized) US overproduction. The intensification of mono-cropped wheat production and specialization through trade marked the shift to agro-industrialization and intense meat production (Friedmann and McMichael 1989; McMichael 2009). This period signaled a widening rift between land and people as well as nations and cultural crops, intensifying the commodification of land and labor. Rather than producing for domestic populations, nations were now producing high-yielding cash crops for global markets, squeezing farmers and farmland for surplus accumulation. Peasant lands were consolidated to facilitate transnational food production, just as plots on marginal lands were subdivided to quell resistance and unrest (McMichael 2009). Over time, as land and people became urbanized, more food was bought instead of grown.

Now, many academics argue that we are in a third (corporate) food regime. From the 1980s onwards, there has been a marked shift towards intensive global and national deregulation of food production (Burch and Lawrence 2009; Campbell 2009; Campbell and Dixon 2009; Friedmann 2009). In developing countries, the dismantling of tariffs, price guarantees, and extension systems (as part of structural adjustment and free trade) led to dramatic reductions in domestic food surplus (Holt-Giménez and Shattuck 2011). Northern governments, corporations and institutions have provided uneven subsidies and trade policies to prop up massive cereal and grain production for export as feed and food aid, disabling local market structures and undermining livelihoods. The Global North continues to import a range of fruits, vegetables and meat, forcing Southern countries to restructure their agricultural sectors for export (McMichael 2009). In the Global South and North, the third food regime has involved the accumulation of large tracts of land and capital for intensive, mechanized mass-produced food, fuel and feed for domestic and international production and consumption (McMichael 2009). Concurrently, the expansion of the agro-food trade and monopoly of agro-food corporations led to the super-marketization of countries such as the US and soon after, parts of Brazil, India and China (McMichael 2005, 2009). Each successive food regime enabled the US and Britain to gain political and economic power to “[…] determine not only what will be produced and where it will go, but also who will profit from agriculture and who will be vulnerable to food crises” (Winders 2009, p. 316). The ‘financialization of agriculture’ represents an extension of such accumulation, with new market actors pushing up food prices through excessive speculation on food commodity markets (Burch and Lawrence 2009; Clapp and Helleiner 2012).Footnote 2 These factors have increased the price and amount of food available in the global food supply chain, driving record profits for food corporations, but pricing out marginalized people and small-scale farmers (Martine et al. 2008).

Debates continue about how food production is organized within large-scale, corporatized agriculture and capitalism, and whether this indeed constitutes a new or third ‘food regime’ (see Goodman and Watts 1995, 1997). However, regardless of the ‘label’ attached to the current food system, it has resulted in the rapid redistribution and concentration of ownership of land, seeds, and agricultural inputs. The global economic integration of the food systems means that the results of a corporatized food regime have similar impacts across diverse geographies. Likewise, resistance to the third, or corporate food regime, is also present across varied geographies and manifests in many ways. For instance, disconnections of people and food have stoked global food riots among landed and landless peasants, demanding equitable access to and use of food (Magdoff and Tokar 2010). Other forms of resistance have been to empower local communities and re-invent the food system through social networks and food-ways, from the ground up (Campbell and Dixon 2009).

Capitalist agriculture also impacts the places from where it originates. Similar to peasant farmers in the Global South, small and medium-sized US farmers have been unable to make profits and compete with heavily subsidized corporate farms. Small-scale farming in the US is increasingly difficult amidst growing support for agro-industrialism, economies of scale and associated transport and production infrastructure. By 1999, farms larger than 500 hectares constituted 79 % of all US farmland, with the remaining small-scale family farmers subject to precipitous decline (Patel 2007; Holt-Giménez and Shattuck 2011). At the same time, agricultural lands have been subject to urban encroachment, justified by low rent, cheap housing and specialized industrial zones that cater to mass food production and distribution (York and Munroe 2010). As cities expand, capital and wealth is often spatially concentrated in inner city areas, causing increases in ground rents and living costs (Smith 2008). Most often the poor in or near inner city areas are forced to move to lower cost, peripheral areas subject to ghettoization. Here the poor contend with limited employment opportunities, few social welfare provisions, social ostracisation and poor health. The consequences for food security are most pronounced. Kirkpatrick and Tarasuk (2011) note, for example, that inner city ‘high poverty’ households whose rental costs were subject to mounting market pressures (e.g., property values, inflation) had less ‘after-shelter’ income available to purchase sufficient levels of quality food. They found that families with housing costs that consumed more than 30 % of their income were at greater risk of food insecurity (Kirkpatrick and Tarasuk 2011, p. 284). As the inner city poor are squeezed into marginal living areas, they remain at significant risk of food insecurity, poor health and illness, rendering close to 15 % of US households food insecure in 2008 (Kirkpatrick and Tarasuk 2011, p. 284).

Challenging the third food regime

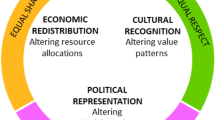

Growing networks of people are responding to the injustices of the current, corporate food regime. Disgruntled by the lack of access to affordable, good food, people are creating their own pathways to food. The rise of urban agriculture in the US may well represent small attempts at social change to “build” and “re-embed food systems” (Friedmann and McNair 2008, p. 257; McClintock 2014), and are of sufficient gravity to be considered a social movement; that is, a sustained, organized public effort of making collective claims concerning redress toward targeted injustices and authority over time and space (Tilly 2004). Two major food movements, food sovereignty and food justice, are popular in the Global South and the urban US, respectively. They offer resistance to the inequalities of corporate food regimes and present a new ‘fair food’ paradigm. We examine these two movements historically, and in the current context of US urban food movements, to understand the similarities and differences between expressions of food sovereignty and food justice. Below, we examine the extent to which US urban food movements are underpinned by food sovereignty and/or food justice ideologies and practices. The literature and insights from food academic-activists are drawn upon to make sense of food sovereignty and food justice concepts as they are re-interpreted and applied to contemporary, community-driven alternatives. The value in this approach lies in understanding the historical underpinnings and trajectories in resisting the corporate food regime and identifying workable pathways toward equitable, community-owned, food systems. Following this, the case studies of Oakland and New Orleans highlight how expressions of food sovereignty and/or food justice have relevance at the community level.

Concepts of food sovereignty and food justice: insights from academic activists

Food sovereignty

Food sovereignty refers to rights to food and production systems, and is an emerging concept that is constantly being defined, re-defined and negotiated according to different actors and contexts. In this section, food sovereignty is considered by drawing upon academic literature, grey literature and the voices of those interviewed for this paper—thereby offering unique insights (from US urban perspectives) into the deployment of the term both in the literature and as empirically grounded in this study.

Originating in South and Central America, the concept of food sovereignty gradually reached the global level through the organized peasant farmer movement, La Via Campesina. Today the concept of food sovereignty has become part of international fora, where it was described at the 2007 Nyéléni International Forum on Food Sovereignty as:

… the right of peoples to healthy and culturally appropriate food produced through ecologically sound and culturally appropriate methods, and their right to define their own food and agricultural systems. It puts the aspirations and needs of those who produce, distribute and consume food at the heart of food systems and policies rather than the demands of markets and corporations… (Nyéléni Declaration on Food Sovereignty 2007, pp. 673–674).

The discourse of food sovereignty has become globally recognized amongst food system scholars, NGOs and food activists—adapting to changing social contexts and political-economic conditions, and as one academic-activist describes, “taking bigger picture politics and placing it in local action.Footnote 3”

Another food systems academic and author describes ‘food sovereignty’ as a term “…born out of peasant struggle [that]…comes from a particular trajectory of being something food security is not.Footnote 4” In the process of sustained dispossession, production and devaluation, peasant farmer groups organized politically, and in 1993 La Via Campesina (The Peasant’s Way) was born. In introducing the concept of ‘food sovereignty’, La Via Campesina challenged whether ‘food security’ could be achieved as it failed to address the political economy of state trade policies and the global food system. In response to the inadequacies of the food security concept and its neoliberal leanings, food sovereignty took root in the 1990s as rural farmers in the Global South felt the pressures of producing for world agriculture. The movement successfully highlighted the inherent power relationships in the food system, and in particular, control, ownership and self-determination in food systems. Through trade schemes like the WTO’s Agreement on Agriculture, southern markets were subjected to global demands, destabilizing countries’ sovereign abilities to produce for their own people (McMichael 2005). Since the mid-1990s, the food sovereignty concept has spread as a global movement where today, La Via Campesina “comprises about 150 local and national organizations in 70 countries from Africa, Asia, Europe and the Americas. Altogether, it represents about 200 million farmers…Footnote 5” Other international groups have also joined the movement including the People’s Food Sovereignty Network and the International Planning Committee for Food Sovereignty (Wittman et al. 2010). International forums, such as the 2007 International Forum on Food Sovereignty in Nyeleni, Mali, and most recently, the 20th anniversary La Via Campesina conference in Jakarta, Indonesia, demonstrate the movement’s growing influence over the past twenty years.

Food movement actors have found the concept of ‘food sovereignty’ to have considerably more rights-based leverage than its relative concept, ‘food security’. Food movement scholar, Hannah Wittman, noted that the concept of food sovereignty is difficult in practice because there is no guidebook and that actors, from activists to governments, frame it differently. In practice, food sovereignty requires localized action plans and government support, however, some governments feel the concept is too radical [especially compared to food security], which can limit collaboration.Footnote 6 International actors advocating for food security development measures (e.g., FAO) recognized that the provision of ‘food security’ required much more work than governments and markets could offer in reallocating food supplies (Holt-Giménez and Shattuck 2011). Consequently, in 1996, the FAO revised food security’s meaning to encompass the physical and economic needs of citizens, communities and states. In doing so, however, the FAO “…avoided discussing the social control of the food system” (Patel 2009, p. 665). As a result, the global ‘food security’ discourse persists in line with neoliberal doctrine, emphasizing market and trade orientation over the rights to self-determine food systems.

Despite its success in consolidating a food movement amongst peasant farms in the Global South, the food sovereignty concept has been slow to spread within US food activism. As an activist and food policy scholar notes, food sovereignty “…tended to be a white concept that underserved communities didn’t hear about…We have the US Food Sovereignty Alliance…[but] they aren’t from the neighborhoods, they are white, so there are a lot of barriers to cross.Footnote 7” Another food movement scholar further describes how “Food sovereignty puts the emphasis back on production which fits urban agriculture, while not farmers markets. It takes the focus away from poor communities of color in the cities which food justice come out of and put it on the romanticization of poor peasants in the global south…It’s sort of a depoliticizing move.Footnote 8” While Northern organizations like the US Food Sovereignty Alliance (USFSA) reflect similar goals as global partners like La Via Campesina, the food sovereignty approach has yet to gain widespread momentum. Yet, with eighty percent of the US population living in urban areas (WHO 2011), it is curious that food sovereignty has gained so little traction in the US.

Food justice

Like the ‘environmental justice’ movement that burgeoned in the US in 1960s and 1970s in response to environmental inequalities faced by ‘people of color’ (Bullard 2000), the ‘food justice’ movement seeks to address injustices that disproportionately impact upon people based on race and class (Gottlieb and Joshi 2010; Mares and Alkon 2012). Perhaps the best-known expression of the food justice movement is the Black Panther Party’s ‘Free Breakfast for School Children Program’, which began in Oakland in 1969 and spread throughout the US (Holt-Giménez and Wang 2011). Decades on, food justice remains high on the community agenda and “… [is] possibly the largest and fastest growing grassroots expression of the food movement” (Holt-Giménez and Shattuck 2011, p. 124). A food movement scholar explains further as to why food justice [rather than food sovereignty] has spread in the US, “…food justice because they expect the state to give them that. I think this is the fundamental ideological piece of why food sovereignty doesn’t resonate in the US.” He elaborated that “…people from the Global South understand capital and they have always had to protect themselves from capital…Footnote 9”.

Inequality and injustices paralleling race and class lines are still the key catalysts for US food justice movements. African-Americans and Hispanics populate many low-income areas of US cities that can be described as food deserts. Gottlieb and Joshi (2010, 43) note a pervasive trend of limited access to fresh food that relates directly to “health related disparities based on race, ethnicity and income” in communities across the US. In a country of ‘abundance’, fifteen percent can be described as food insecure, with African-American and Hispanic populations bearing much of this burden (Patel 2009; Bishaw 2012).

Many civil society organizations currently work across the US to address issues of food insecurity in urban spaces. The strategies of such organizations include rural–urban food buying groups and co-operatives, community supported agriculture, urban agriculture and farmers’ markets. These strategies are based on localized food systems with short supply chains, and have become increasingly popular across the US. Of these, farmers markets represent a growing success story. From 2010 to 2011, the number of US farmers’ markets rose 17 % to reach 7175, and by 2014 more than a 1000 more markets were registered, reaching a total of 8268 (USDA 2011, 2014). While these local strategies are positive for linking farmers to urban communities and shortening supply chains, how they address ‘justice’ and bigger political issues requires further exploration. In particular, food system scholars have questioned whether such market-based strategies re-create similar, less accessible food options (Alkon and Mares 2012) and are geared more toward middle-class consumers (DuPuis and Goodman 2005); or conversely, that they “…ignore the ways that racial and economic privileges pervade both conventional and alternative food systems” (Alkon and Mares 2012, p. 4).

How then, does food sovereignty relate to food justice in the broader context of US urban food movements? In practice, US food movements mobilize communities to solve local problems, which Holt-Giménez and Shattuck (2011) characterize as both its strength and weakness. While localized, market-based strategies may bring about positive changes regarding access to fresh food with reduced food miles, they fail to address the bigger, structural and political issues that define who has the power over access to food, with control remaining with the privileged who can afford niche products (Alkon and McCullen 2010). The overall weakness of market-based approaches to food inequalities is reflected in how locally-based strategies do not engage with the bigger politics of the corporate food regime that governs urban access to affordable, healthy food choices (Holt-Giménez and Shattuck 2011). Instead, food justice strategies ‘work around’ the larger food system in small ways to provide communities food access. Similarly, Alkon and Mares (2012) find that food justice projects in Oakland and Seattle do not engage—and in many cases are not aware of the overarching neoliberal constraints—as a food sovereignty approach demands.

Given its historical roots, the food sovereignty approach is much more political, directly challenging the corporate food regime and embedded power relationships, seeking structural change in international (and national) food systems. In contrast to the food justice approach described above, the food sovereignty movement has spread across countries in a ‘boomerang pattern’ (Keck and Sikkink 1998; Friedmann and McNair 2008). We explore below the context, conditions and constraints of food sovereignty finding broader traction in US urban food movements.

Food movement case studies: Oakland and New Orleans

The cities of Oakland, California and New Orleans, Louisiana were selected as case studies in order to examine the characteristics, motivations, strategies and practices of US urban food activism. Oakland was selected because of its long history in activism around the environment, structural racism, and food production; and New Orleans because of its recent surge of urban food movements in the years following Hurricane Katrina, which devastated much of the city. In both cities, grass-roots actors and local urban communities are gaining new awareness of how their food is produced and distributed.

Locating concepts, strategies and practices in Oakland and New Orleans

Oakland is a city marked by lines of inequality, where neighborhoods like West Oakland have “… 30,000 residents, thirty-six convenience and liquor stores and a single supermarket” (Patel 2007, 250). Not surprisingly, the same ‘food desert’ neighborhoods of Oakland that gave rise to the historic Black Panthers movement in the 1960s, are now home to many ghost towns, which sit opposite to the elite food markets in Berkeley and the Bay Area’s trendy, high dollar restaurants. New Orleans, like Oakland, is known for its structural racism with fresh scars left by Hurricane Katrina’s high water marks in communities of color. While it is a city and culture known for its love of food, it is also one of the unhealthiest in the US (Olopade 2009). Before Hurricane Katrina, the city’s food access was poor, but as large numbers of people, businesses and grocery stores fled the city with the 2005 hurricane, food access and availability worsened (Olopade 2009). Now, the city has one of the highest rates of obesity in the US, as many poor neighborhoods have little access to fresh food or supermarkets, and instead have convenience shops filled with alcohol and calorie-rich snack foods (Rose et al. 2008; Bodor et al. 2010). In response to these food insecurities, people in both cities have begun to farm on vacant lots and unused urban land.

Oakland

Oakland (and the wider San Francisco Bay area) has a number of community-based organizations, market-based businesses and alternative, social enterprises that address issues of food insecurity. These include CSA schemes, local farmers’ markets, community gardens, and educational outreach programs. Twelve people, consisting of a mix of farmers, activists, educators, food policy institutes and NGOs were interviewed in Oakland and the Bay area.

Phat Beets, a community organization in North Oakland, advertises “weekly workshops, local produce, youth businesses, food justice!Footnote 10” These practices are similar to those of a number of other organizations in the area, such as Hayes Valley Farm, Alemany Farm, and City Slicker Farm, who promote food justice to young, low-income and racially diverse communities. Phat Beets mission statement says that they aim:

… to create a healthier, more equitable food system in North Oakland through providing affordable access to fresh produce, facilitating youth leadership in health and nutrition education, and connecting small farmers to urban communities via the creation of farm stands, farmers’ markets, and urban youth market gardens. (Phat Beets website 2010)

Across the Bay area, the concept of ‘food justice’ resonated with key informants and was prominent in their language and mission statements. But how was food sovereignty understood? Upon asking several respondents about how their work related to food sovereignty, most first identified with food justice and tended to interpret food sovereignty in terms of the former, demonstrating how established the food justice concept was in the region. For instance, during a Phat Beets market day, a volunteer conflated food sovereignty with the Phat Beets’ mission of ‘food justice’: “Yeah, [food sovereignty] is definitely a part of our mission …. [we want] to create an equitable food system and food justice, to bring people out and allow folks to grow and sell their own food…but I really think it’s about teaching people here.Footnote 11”

Likewise, Alemany Farm, one of the oldest and largest farms in the San Francisco area, sits next to 165 units of public housing, and aims to “…sow the seeds for economic and environmental justice.Footnote 12” A co-manager described their work as growing “as much food as possible to distribute to folks of all economic strata.Footnote 13” When asked if and how Alemany Farm’s work related to food sovereignty, he, like the Phat Beets informant, related it to the educational aspects of food justice: “I actually think having our 3rd graders out and having them work in the garden helps increase food sovereignty by a degree…but it is skill sharing and they take those skills to their backyard, and in their neighborhood.Footnote 14” A teacher with Garden for the Environment, an educational community garden with workshops for local residents in the Bay area, related her work to food sovereignty: “When I think of food sovereignty I think of people being able to choose what it is they want to grow. And the urban manifestation of that is empowerment. So I think more directly in terms of empowerment.Footnote 15” A respondent from Outdoor Afro, an urban youth environmental education organization with a booth at Phat Beets’ market day, said she did not know the term of food sovereignty, but could identify with its meaning in terms of food justice. She recognized the importance of building support within the community, and for these market models to not only provide access to healthy and fresh food, but to also address social inequalities.

When speaking about food sovereignty, the Outdoor Afro respondent also related how alternative food movements often miss the importance of building networks across diverse social groups. According to her, a key to the success of addressing food inequalities required connections with communities of color—the very basis of common interpretations of food justice:

I hear organizations say we tried this and nobody comes. I challenge organizations like that. Are your staff people of color? Do you go to the community events? A lot of people aren’t willing to do that work. It takes a lot of relationship building and less about the thing itself and more about those relationships. (Rose Dean, Outdoor Afro, Oakland, 30 July 2011)

The relationship-building aspect of a food movement was also relevant to Mandela Market Place, a community based organization in West Oakland. This organization aimed to set up a wholesale distribution center to better support the region’s family farmers while providing accessible, fresh produce to the local area. Established in 2001—its mission statement is “to improve health, create wealth, and build assets through cooperative food enterprises in low income communities.Footnote 16” It reports to achieve this through partnering with local residents, community-based businesses and family-farmers. When asked about whether the organization found the term ‘food sovereignty’ useful, the Mandela Market Place spokesperson noted that she only recognized the term from other food policy organizations in Oakland (i.e., Food First; the Oakland Institute). Despite not using the term often within her own organization, she related her understanding of food sovereignty by sharing how, in practice, it was difficult to compete with major food corporations and shift people’s ‘convenience mindset’ within West Oakland. She says, “… it takes years to build the local economy… there is just so much marketing, convenience, and comfort about McDonalds that we have to fight…Footnote 17” She added, “I don’t care how much food we think we can grow in the urban setting, we have to keep connections to our family farms or Monsanto moves in. Urban centers are the place for rural farmers to make their living.Footnote 18” Many interviews showed that their understanding and practice of food sovereignty was reflected in broader understandings of food justice; that is, teaching and outreach, building social connections and actively supporting local communities and economies in terms of equitable access to low cost, quality food and particularly for non-white residents experiencing poverty and other forms of marginalization.

New Orleans

New Orleans, like Oakland, showed a mix of practices that aligned somewhat closer to food justice but also partly encompassed elements of food sovereignty. Here, eleven civil society organizations, activists and urban farmers were interviewed, including grass-roots organizations involved in city gardening to regional level networking and policy organizations.

The New Orleans Food and Farm Network (NOFFN) is an organization that works to create fresh food access among the poorer neighborhoods in New Orleans. Similar to its West Oakland counterpart, the Mandela MarketPlace, NOFFN’s representative expressed the need for stronger links between rural and urban areas. He argued that: “…local food sheds will be the alternative and the expansion of our work when oil makes Californian lettuce expensive… NGOs must cooperate for a bigger system to support small agriculture.Footnote 19” He highlighted the importance of NGO and farmer networks in building an alternative food system for the greater New Orleans area, offering a vision that extended beyond the food justice discourse to a broad conceptualization of a resilient system. He spoke of this resilience in terms of ‘local food economies’, rather than ‘food justice’ or ‘food sovereignty’.

Many local respondents stated that supporting the ‘local economy’ was more important than ‘knowing where your food comes from’. As the NOFFN respondent noted, “… down here it is more about having good food and less of where it comes from… [but] there is a basis for wanting to support your own economy…there are movements to protect seafood, etc., but vegetables are harder.Footnote 20” Two prominent urban food activists echoed this view. NOLAFootnote 21 Green Roots spokesmanFootnote 22 shared that his business model was to link urban and community gardens, compost programs and local restaurants to support the local food economy. Likewise, the aim of ‘Our School at Blair Grocery’, an alternative school based in a poor neighborhood severely hit by Hurricane Katrina, was to secure land through grant funding, grow and sell food, contribute to the local food economy and secure employment for local young people. The spokesperson there noted that local food was about building relationships: “if I can employ kids to sell a local egg and cheese sandwich and people know those people then we can build relationships…Poor people don’t want to support local farmers just because of that, it’s more about supporting those relationships.Footnote 23” Similarly, another well-known local farmer, ‘the Garden Guy’, claimed “the food justice movement has made gardening a viable economic activity… If it hadn’t been for NOFFN and Holly GroveFootnote 24 I would not be a market gardener.Footnote 25”

While much of the sentiment around urban food movements in New Orleans contains elements of food sovereignty, such as the right to determine food systems, the city’s urban actors did not begin from the ideological standpoint of ‘food sovereignty’. Rather, the reasons were more localized, immediate and pressing, and generally linked to elements of food justice for ‘people of color’. A farmer-activist from the Delachaise Community Gardens gives a frank opinion:

we started this because we had two blighted lots, no bigger ideas. There was a whorehouse, crack house and a bad place for kids. And there was nowhere for affordable groceries. We knew we wouldn’t be able to feed a lot of people, but it’s a start. (Joshua Quince, New Orleans, 9 August 2011)

From a different perspective, a New Orleans fisherwoman in the Gulf of Mexico thought that food sovereignty looked very different in the US, and would be slow to spread influence (compared to the Global South) because:

until someone in America is hungry, food sovereignty is never gonna be the same thing to somebody who can go next door and get a Burger King sandwich … the food movements in the US are all perceived as being upper class people or back to the land. Well, ya know, people in the city don’t have land and they don’t have money to buy organic eggs. Big families can’t afford Whole Foods… that’s the whole problem. (Elizabeth Maner, New Orleans, 30 September 2011)

She added,

I see a lot of similar things in the US but it’s not called food sovereignty. Here people don’t know what you are talking about if you use those words. But things are similar, trading, bartering, keeping it in your local system. Every year I see it getting better and better…

Many of the New Orleans interviews show that practices of food sovereignty exist in how activists, farmers and NGOs understand their roles in supporting community food networks, social relationships and the local economy. As such, they were arguably engaged in the practice of food sovereignty. However, food justice was a term more actors identified with as both an ideology and practice, which incorporated the ideals of food sovereignty whilst also keeping race politics on the agenda. The divide between urban food movements vs. ‘foodie’ movements, associated with upper middle class ‘organic’ consumers is the fundamental divide between many US urban food movements and more political, global movements, like food sovereignty. In both New Orleans and Oakland, many actors used practices that emphasized consumer choice through lower-priced markets, community led grocery stores, CSAs and educational urban gardens based in low-income neighborhoods. However, while many of these practices were originally informed by grass roots motives, there were sustained efforts to connect produce with the ‘choices’ and preferences of white communities. Other actors in New Orleans and Oakland noted the difficulties of reaching poorer neighborhoods and the time and resources required, and thus kept their organizations supported through reaching more ‘foodie’ neighborhoods or through partnering with grants or larger businesses, showing how “…neoliberalization incorporates, co-opts, constrains and depletes activism…” (Bondi and Laurie 2005, p. 395).

Discussion

In both Oakland and New Orleans, food justice grew out of racial inequalities, and was initially designed to promote food access, leading to more distributive food movements, such as the Black Panthers’ Free Breakfast Program. From these radical roots, food justice spread throughout the urban US and NGO realm to address social inequity. Slowly, however, the critical language of food justice became depoliticized. Informants shared that many US food justice movements had limited political scope and weak associations between the state and food production compared to movements like food sovereignty. These depoliticizing trends in US food movements have made it difficult for actors to build substantial support and power for what is ‘alternative’. While many organizations visited in Oakland and New Orleans focused on small-scale ways to improve neighborhood access, many had limited success due to their project size or staff (especially those depending on volunteers) and poor communities’ resource base (time, money, transport, knowledge etc.). As Guthman (2006, p. 1180) explains, “for activist projects, neoliberalization limits the conceivable because it limits the arguable, the fundable, the organizable, the scale of effective action, and compels activists to focus on putting out fires.” The limiting effect neoliberalism brings to urban food movements, constrains power and limits interest to small-scale neighborhood actions.

In contrast to food justice, informants shared that food sovereignty was first about production and over time the concept adapted to confront the trade politics of the corporate food regime. Alkon and Mares (2012, p. 26) argue that the strategy of food sovereignty gives both a critique of capitalist agriculture and strategies for transformation. While these radical strategies have spread across the Global South over the past twenty years, movements in the urban US have been relatively quiet. This study points to several reasons: First, the history and context of US urban centers demanded that food and other social movements address race, which is deemed missing in food sovereignty discourse from a North American perspective. Second, food sovereignty’s radical discourse would have to find a place within a stifling corporate environment, challenging entrenched corporate food economies, people’s minds and government leanings (and expectations). Fairbairn (2011) argues similarly, noting that food sovereignty discourse loses political momentum with domestic issues, while maintaining its momentum for international issues through the support of white NGOs. Our findings echo this point. Many respondents related food sovereignty to individual education improvement and local economic development rather than claiming political space and rights to food and land globally, further demonstrating the depoliticizing effect neoliberalism has on US strategies for food sovereignty (Fairbairn 2011).

In the two cities examined, the urban agricultural practices varied between food justice and food sovereignty in how they responded to food insecurity. The differences in practice across both movements have been strongly influenced by capitalist agriculture and neoliberalism, particularly the socio-political and economic constraints and opportunities emerging from each. Crucial is that neoliberalism’s reach is not only to ‘big institutions’ and markets but also the spaces in between where social movements are often forged (Peck and Tickell 2002, p. 387). In both cities, neoliberal discourse informed the way society—in this case, community organizations, small businesses, activists and NGOs—responded to issues of food insecurity and mediated the extent to which northern actors formed their goals, strategies and practices. From markets to cooperatives, from ‘sovereign’ economies to rural–urban partnerships to educational workshops, US urban food movements practiced many elements of food sovereignty; however, many of those practices were limited in their politically ‘transformative’ potential.

As many food movements align with ‘foodie’, upper-class markets to remain viable and sustainable, they necessarily miss food sovereignty practices. That is not to say that all market approaches are bad, but simply, many can be limited in whom they can appeal to considering time and resources. Food sovereignty practices were found in the bigger ideas of why actors supported and initiated urban food movements. In New Orleans, for instance, supporting local food production, community businesses and the regional economy were central for everyone—especially due to the loss of people and commerce post-Katrina. Many movements sought to re-connect the social and business links between gardens, communities, and restaurants, emphasizing the importance of building social relationships through multiple actors, something important to food sovereignty.

Overall, the activism within urban agriculture in Oakland and New Orleans failed to reflect the ideology of food sovereignty per se, but engaged many elements in practice, often with the aim to educate and address injustices around access and mindsets that affect the urban poor. While many informants understood and shared similar views with food sovereignty, they related to the concept of food justice more, as in supporting local economies and poor neighborhoods. As such, these discussions failed to grasp the larger picture of food sovereignty’s initiative to address the bigger politics that inform food production and its connections to social and racial inequalities. While many of these urban food movements are pushed toward similar market forms and class-based injustices, herein lies the opportunity for the food sovereignty movement to recreate itself within the US.

The challenge for both food sovereignty and food justice movements, especially in urban US, is recognizing how their strategies are influenced by neoliberalism and finding ways to navigate around the omnipotence of the corporate food regime. Guthman (2006) states that the “politics of the possible” is shaped through neoliberal political discourse and societal structures that change radical food movements to individualized consumption (Keck and Sikkink 1998), reconfiguring the original scope and claims. Our results suggest that food justice movements, while positive in intent, often employed market approaches to improve access and address what the state or policies ignored. While some interviewees shared that this strategy was successful in reaching poor communities, some did not, highlighting needs for strengthening designs in the movement. The difficult question therefore is how to create space, especially for movements like food sovereignty, in such entrenched neoliberal environments whose food system is characterized by a corporate food regime.

Conclusion

This paper examined how food sovereignty is unfolding in US urban food movements. Interviews with food movement experts and activists in Oakland and New Orleans show food justice has more relevance as a working concept. We find elements of food sovereignty within the concepts, strategies and practice of food movements, but find they are heavily influenced and weakened by the neoliberal settings within which they exist. Neoliberalism both heavily frames and is embodied in the corporate food regime, and is a cause of food system inequalities as well as a barrier in effecting change. The historical differences between food sovereignty and food justice movements have shaped the scale, depth and context of their message today. Food sovereignty, founded by peasant farmers in the Global South, has grown to be an international call for equal, democratized food systems. Similarly, food justice, founded to fight structural racism and access to resources, focused on the distribution of food within low-income communities and did not challenge the larger politics of food production. As such, the political, international, and ideological changes called for by food sovereignty were seldom present in US urban food movements.

Nevertheless, the many US urban food justice movements formed by actors excluded and marginalized from the modern food system mirrored similar experiences of peasant farmers in the Global South, from where the food sovereignty movement arose (Schiavioni 2009). While US urban food movements in the form of community supported agriculture, urban gardens and farmers’ markets did not make explicit links to food sovereignty, the movement was recognized and is being used by larger, international organizations such as the US Food Sovereignty Alliance. Moreover, deeper reasons for why actors were organizing urban gardens, CSAs, and building rural–urban connections within and outside their cities showed similar claims (in purpose and intent) for a new, alternative food system. Ideally, both movements could build upon one another: food justice spurring short-term action and rights in domestic contexts, while food sovereignty movements support longer-term national, regional and international networks and political action. More crucial is that food sovereignty proponents learn how to both negotiate and undermine the neoliberal settings that favor the corporate food regime at both local and global scales.

Notes

The original names of academics interviewed on the concept of food sovereignty in the US have been kept upon permission. Pseudonyms have been given to all other respondents in the Oakland and New Orleans areas.

Similarly, corporate investors are acquiring vast tracts of land in the Global South, particularly in Africa, for timber plantations, food and biofuels production (Lyons et al. 2014).

Interview with Madeleine Fairbairn, New York City, 25 July 2011.

Interview with Raj Patel, San Francisco, 26 July 2011.

La Via Campesina’s website: http://viacampesina.org/en/index.php?option=com_content&view=category&layout=blog&id=27&Itemid=44.

Key informant interview with H. Wittman, 26 July 2011.

Key informant interview with food policy scholar, Oakland, 28 July 2011.

Interview with Alison Alkon, Oakland, 1 August 2011.

Key informant interview with food policy scholar, 28 July 2011.

Phat Beets website: http://www.phatbeetsproduce.org/about/mission-statement/.

Interview with Phat Beets volunteer Sherri Oakes, Oakland, 30 July 2011.

See Alemany Farm website: http://www.alemanyfarm.org.

Interview with Alemany Farm co-manager, Tim Bales, San Francisco, 22 September 2011.

Interview with Alemany Farm co-manager, Tim Bales, San Francisco, 22 September 2011.

Interview with Lisa Palm, Garden for the Environment, San Francisco 2 August 2011.

See Mandela MarketPlace’s website: http://www.mandelamarketplace.org/.

Interview with Nora Pines, Oakland, 3 August 2011.

Interview with Nora Pines, Oakland, 3 August 2011.

Interview with Robert Lohane, New Orleans, 8 August 2011.

Interview with Robert Lohane, New Orleans, 8 August 2011.

NOLA stands for New Orleans, Louisiana.

Interview with Grant Edwards, New Orleans, 8 August 2011.

Interview with Derek Glenn, New Orleans, 31 August 2011.

Holly Grove is a neighborhood garden, market and resource center named after the community it is in.

Interview with Jason Green, New Orleans, 6 August 2011.

Abbreviations

- CSA:

-

Community supported agriculture

- FAO:

-

Food and Agricultural Organization

- NGO:

-

Non-governmental organization

- NOLA:

-

New Orleans, Louisiana

- NOFFN:

-

New Orleans Food and Farm Network

- USDA:

-

United States Department of Agriculture

- USFSA:

-

United States Food Sovereignty Alliance

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Alemany Farm. http://www.alemanyfarm.org Accessed 2 October 2011.

Alkon, A., and C.G. McCullen. 2010. Whiteness and farmers markets: Performances, perpetuations…contestations? Antipode 43(4): 937–959.

Alkon, A., and T. Mares. 2012. Food sovereignty in US food movements: Radical visions and neoliberal constraints. Agriculture and Human Values 29(3): 347–359.

Allen, P., M. FitzSimmons, M. Goodman, and K. Warner. 2003. Shifting plates in the agrifood landscape: The tectonics of alternative agrifood initiatives in California. Journal of Rural Studies 19: 61–75.

Bello, W. 2009. The food wars. London: Verso.

Bishaw, A. 2012. Poverty 2010 and 2011: American community survey briefs. United States Census Bureau. http://www.census.gov/prod/2012pubs/acsbr11-01.pdf. Accessed 26 August 2013.

Bodor, J.N., V.M. Ulmer, L.F. Dunaway, T.A. Farley, and D. Rose. 2010. The rationale behind small food store interventions in low-income urban neighborhoods: Insights from New Orleans. The Journal of Nutrition 140: 1185–1188.

Bondi, L., and N. Laurie. 2005. Working the spaces of neoliberalism: Activism, professionalisation, and incorporation. Antipode 37(3): 393–401.

Bullard, R.D. 2000. Dumping in Dixie: Race, class and environmental quality, 3rd ed. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Burch, D., and G. Lawrence. 2009. Towards a third food regime: Behind the transformation. Agriculture and Human Values 26: 267–279.

Burns, R. 2014. Atlanta’s food deserts leave its poorest citizens stranded and struggling. The Guardian. 17 March. http://www.theguardian.com/cities/2014/mar/17/atlanta-food-deserts-stranded-struggling-survive Accessed 30 March 2014.

Campbell, H. 2009. Breaking new ground in food regime theory: Corporate environmentalism, ecological feedbacks and the ‘food from somewhere’ regime? Agriculture and Human Values 26(4): 309–319.

Campbell, H., and J. Dixon. 2009. Introduction to the special symposium: Reflecting on twenty years of the food regimes approach in agri-food studies. Agriculture and Human Values 26(4): 261–265.

Clapp, J., and E. Helleiner. 2012. Troubled futures? The global food crisis and the politics of agricultural derivatives regulation. Review of International Political Economy 19(2): 181–207.

DuPuis, E.M., and D. Goodman. 2005. Should we go “home” to eat?: Toward a reflexive politics of localism. Journal of Rural Studies 21(3): 359–371.

Fairbairn, M. 2011. Framing transformation: The counter-hegemonic potential of food sovereignty in the U.S. context. Agriculture and Human Values 29(2): 217–230.

Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). 2008. The state of food insecurity in the world, high food prices and food security—threats and opportunities. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. http://www.fao.org/docrep/011/i0291e/i0291e00.htm. Accessed 27 September 2011.

Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). 2010. The state of food insecurity in the world: Addressing food insecurity in protracted crisis. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. http://www.fao.org/docrep/013/i1683e/i1683e.pdf. Accessed 27 September 2011.

Friedmann, H. 2009. Discussion: moving food regimes forward: Reflections on symposium essays. Agriculture and Human Values 26: 335–344.

Friedmann, H., and A. McNair. 2008. Whose rules rule? Contested projects to certify ‘local production for distant consumers’. In Transnational agrarian movements: Confronting globalization, ed. S.M. Borras, M. Edelman, and C. Kay, 1–36. Singapore: Blackwell Publishing.

Friedmann, H., and P. McMichael. 1989. Agriculture and the state system: The rise and decline of national agricultures, 1870 to the present. Sociologia Ruralis 24(2): 93–117.

Goodman, D., and M. Watts. 1995. Reconfiguring the rural or fording the divide?: Capitalist restructuring and the global agro-food system. Journal of Peasant Studies 22(1): 1–49.

Goodman, D., and M. Watts. 1997. Agrarian questions: Global appetite, local metabolism: Nature, culture, and industry in fin-de-siècle agro-food systems. In Globalizing food: Agrarian questions and global restructuring, ed. D. Goodman, and M. Watts, 1–32. London: Routledge.

Gottlieb, R., and A. Joshi. 2010. Food justice. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Guthman, J. 2006. Neoliberalism and the making of food politics in California. Geo-forum 39: 1171–1183.

Holt-Giménez, E., and A. Shattuck. 2011. Food crises, food regimes and food movements. Journal of Peasant Studies 38(1): 109–144.

Holt-Giménez, E., and R. Patel. 2009. Food rebellions!. Oxford: Pambazuka Press.

Holt-Giménez, E., and Y. Wang. 2011. Reform or transformation?: The pivotal role of food justice in the U.S. food movement. Race/Ethnicity: Multidisciplinary Global Contexts 5(1): 83–102.

Keck, M., and K. Sikkink. 1998. Activists beyond borders. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Kirkpatrick, S., and V. Tarasuk. 2011. Housing circumstances are associated with household food access among low-income urban families. Journal of Urban Health: Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine 88(2): 284–296.

La Via Campesina. International Peasant’s Movement. http://viacampesina.org/en/index.php?option=com_content&view=category&layout=blog&id=27&Itemid=44. Accessed 20 September 2011.

Lagi, M., Y. Bar-Yam, K.Z. Bertrand, and Y. Bar-Yam. 2011. The food crises: A quantitative model of food prices including speculators and ethanol conversion. London: New England Complex Systems Institute.

Lang, T. 2010. Crisis? What crisis? The normality of the current food crisis. Journal of Agrarian Change 10(1): 87–97.

Lyons, K., C. Richards, and P. Westoby. 2014. The darker side of green: Plantation forestry and carbon violence in Uganda. California, CA: Oakland Institute.

Magdoff, F., and B. Tokar. 2010. Agriculture and food in crisis: Conflict, resistance and renewal. USA: Monthly Review Press.

Mandela Marketplace. http://www.mandelamarketplace.org/. Accessed 5 October 2011.

Mares, T., and A. Alkon. 2012. Mapping the food movement: Inequality and neoliberalism in four food discourses. Environment and Society 2(1): 68–86.

Martine, G., J.M. Guzman, and D. Schensul. 2008. The growing food crisis: Demographic perspectives and conditioners. Food and Agriculture Organization. http://km.fao.org/fileadmin/user_upload/fsn/docs/UNFPAFoodCrisis_DemographicsNov19-versionMarch20.pdf. Accessed 17 September 2011.

Maye, D., L. Holloway, and M. Kneafsey (eds.). 2007. Alternative food geographies: Representation and practice. Oxford, UK: Emerald Group Publishing.

McClintock, N. 2008. From industrial garden to food desert: Unearthing the root structure of urban agriculture in Oakland, California. ISSI Fellows Working Papers. Berkeley, CA: University of California, Berkeley.

McClintock, N. 2014. Radical, reformist, and garden-variety neoliberal: Coming to terms with urban agriculture’s contradictions. Local Environment: The International Journal of Justice and Sustainability 19(2): 147–171.

McMichael, P. 2005. Global development and the corporate food regime. In New directions in the sociology of global development, eds. F.H. Buttel and P. McMichael, 11, 269–303. Oxford: Emerald Publishing.

McMichael, P. 2009. A food regime genealogy. The Journal of Peasant Studies 36(1): 139–169.

McMichael, P. 2012. The land grab and corporate food regime restructuring. Journal of Peasant Studies 39(3–4): 681–701.

Nyéléni Declaration on food sovereignty. 2007. In Food sovereignty, ed. R. Patel, Journal of Peasant Studies 36(3): 673–675.

Olopade, D. 2009. Green shoots in New Orleans. The Nation. 21 September. http://www.thenation.com/article/green-shoots-new-orleans?page=0,1. Accessed 30 October 2011.

Patel, R. 2007. Stuffed and starved: Markets, power and the hidden battle for the world’s food system. London, UK: Portobello Books.

Patel, R. 2009. What does food sovereignty look like? Journal of Peasant Studies 36(3): 663–706.

Peck, J., and A. Tickell. 2002. Neoliberializing space. Antipode 34(3): 380–404.

Phat Beets. 2010. http://www.phatbeetsproduce.org/about/mission-statement/. Accessed 10 October 2010.

Rose, D., J.N. Bodor, C. Swalm, J.C. Rice, T.A. Farley. 2008. Disparities in the food environment in New Orleans and Southern Louisiana. In National Symposium on Race, Place, and the Environment after Katrina, Deep South Center for Environmental Justice at Dillard University; New Orleans, LA.

Sassen, S. 1990. Economic restructuring and the American city. Annual Review of Sociology 16: 465–490.

Schiavioni, C. 2009. The global struggle for food sovereignty: From Nyeleni to New York. Journal of Peasant Studies 36(3): 682–689.

Smith, N. 2008. Uneven development. Nature, capital and the production of space. Athens, GR: The University of Georgia Press.

Tilly, C. 2004. Social movements, 1768–2004. Boulder, CO: Paradigm Publishers.

USDA. 2011. Farmers market and local food marketing: Farmers market growth 1994–2011. United States Department of Agriculture. Accessed 14 November 2011.

USDA. 2014. National count of farmers markets directory listings. United States Department of Agriculture. http://www.ams.usda.gov/AMSv1.0/ams.fetchTemplateData.do?template=TemplateS&navID=WholesaleandFarmersMarkets&leftNav=WholesaleandFarmersMarkets&page=WFMFarmersMarketGrowth&description=Farmers%20Market%20Growth&acct=frmrdirmkt. Accessed 28 September 2014.

Weis, T. 2007. The global food economy: The battle for the future of farming. London, UK: Zed Books.

WHO. 2011. United States of America: Health profile. World Health Organization. http://www.who.int/gho/countries/usa.pdf. Accessed 14 November 2011.

Winders, B. 2009. The vanishing free market: The formation and spread of the British and US food regimes. Journal of Agrarian Change 9(3): 315–344.

Wittman, H. 2011. Food sovereignty: A new rights framework for food and nature? Environment and Society: Advances in Research, Special Issue on Food 2(1): 87–105.

Wittman, H., A.A. Desmarais, and N. Wiebe (eds.). 2010. Food sovereignty: Reconnecting food, nature and community. Winnipeg: Halifax Publishing.

York, A.M., and D.K. Munroe. 2010. Urban encroachment, forest regrowth and land-use institutions: Does zoning matter? Land Use Policy 27: 471–479.

Acknowledgments

This study would not have been possible without the time and effort of numerous urban farmers, activists and academics who shared their thoughts on food justice and food sovereignty meanings and practices. Dr Richards also acknowledges support from the Australian Research Council Discovery Grant DP110102299, The New Farm Owners: Finance Companies and the Restructuring of Australian and Global Agriculture. Additional thanks go to two anonymous reviewers for their constructive feedback.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Clendenning, J., Dressler, W.H. & Richards, C. Food justice or food sovereignty? Understanding the rise of urban food movements in the USA. Agric Hum Values 33, 165–177 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-015-9625-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-015-9625-8