Abstract

This research situates new farmers within the counter-urbanization phenomenon, explores their urban–rural migration experiences and examines how they are becoming a part of the rural agricultural landscape. Key characteristics in new farmers’ sense of place constructions are revealed through an ethnographic study conducted in southern Ontario, Canada, during the summer of 2009. Using a sense of place framework comprised of place identity, place attachment, and sense of community, this research details a contemporary concept of place to provide a fresh perspective on new farmers. It uncovers underlying motivations, goals, and values attached to rural agricultural landscapes as well as the “everyday” interactions and challenges experienced by those transitioning into rural farming communities. New farmers are found to draw unevenly from both the physical and social landscape of the urban and rural environments in the creation of a sense of place. This finding raises important questions about the socio-spatial dynamics that underscore the place of food and the local food movement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Canadian agriculture is, in part, currently characterized by at least two interesting and somewhat opposing trends. On the one hand, there is a growing interest in local food movements (LFM). This is demonstrated by the demand for more local produce, the emergence of organizations dedicated to local food and agricultural issues, and a growing body of literature adopting food as a lens to examine a range of issues from community health, sustainability education, economic development, and municipal governance (Desjardins et al. 2010; Rojas et al. 2011; Friedmann 2007; Mendes 2007). On the other hand, the rapidly declining farming population raises uncertainties about the trajectory of mainstream agriculture. According to the Census of Agriculture (Statistics Canada 2011a) the farming population fell to an unprecedented low in 2011, while the average age of a Canadian farm operator increased to 54 years old from 52 in 2006. More notably, it marked the first census year in Canada where nearly half (48 %) of the farm operators were ≥55 years old.

Given this situation, advocates within the LFM hope “to leverage new consumer trends to renew [the] farm population by making a clear commitment to helping a new generation of farmers across Canada create successful family businesses” (People’s Food Policy Project 2011). Initiatives encouraging people with little to no rural or agricultural background to take up farming have begun to emerge (e.g., FarmStart, Just Food, the University of British Columbia’s Sowing the Seeds program, and Kwantlen University’s Farm School to name a fewFootnote 1). Often catering to an urban population interested in exploring the agrarian dream, these programs provide participants with fundamental agricultural production and business experiences as part of establishing an economically viable farm business (see Niewolny and Lillard 2010). If successful, these initiatives could give rise to a new generation of back-to-the-land hopefuls who will eventually find their place within Canada’s agricultural landscape.

Coincidentally, in North America a similar counter-urbanization movement took place in the 1960s and 1970s whereby urbanites migrated to more rural areas with the desire to connect with the land and embrace “a kind of social movement resisting the dominant forces promoting capitalist globalization” (Halfacree 2007, p. 5). The success of past “back-to-the-land” movements is difficult to fully discern, but Halfacree, among others, suggests the longevity of these initiatives is questionable as several people returned to their previous lifestyle after attempts at living off the land proved difficult (2006, 2007). More recently, in a study commissioned by the Friends of the Greenbelt Foundation, Mitchell et al. (2007) surveyed 95 alumni of a new farmer training program based in Ontario, Canada and found that approximately a third of the respondents were actively farming. High real estate prices, inadequate agricultural skills, inaccessible financing, and under-developed markets were some of the reasons that contributed to “false starts” for the majority of these farmers. Overall this suggests the farming demographic deficit is propelled by many factors and may not simply be a question of recruitment but also of retention.

Some progress has been made to understand the educational and professional needs of new farmers (Niewolny and Lillard 2010; Mitchell et al. 2007). Still, there is limited research examining the social dimensions of entering the farming community. Some argue the place of food is largely overlooked because “the public-at-large is not being asked to re-connect to context—to the soil, to work (labor), to history, or to place—but to self-interest and personal appetite” (DeLind 2011, p. 279). Others such as Born and Purcell (2006) note the perfunctory use of locality as a proxy for a just food system. They echo DuPuis and Goodman’s desire to see the LFM’s theoretical engagement with place “move away from the idea that food systems become just by virtue of making them local and toward a conversation about how to make local food systems more just” (DuPuis and Goodman 2005, p. 364). Hence, a more critical engagement in the politics of place examining the people, places and processes entangled in the production of food warrants further investigation (Winter 2003; DeLind 2006; Feagan 2007; Hinrichs 2007).

This paper recognizes this knowledge gap and aims to situate new farmers from urban backgrounds within a broader place-making phenomenon. Based on ethnographic research, this paper explores how these new farmers struggle via their day-to-day lives to create their sense of place. Understood as the ability to identify with and feel a sense of “belonging” (Agnew 2005), a sense of place has been acknowledged as an important characteristic linked to community and social sustainability (Stedman 1999; Hargreaves 2004) with applications in resource management (Cheng et al. 2003), urban and social planning (Dempsey et al. 2011) and civic engagement (Lewicka 2005; Gooch 2003). With the practice of agriculture inherently grounded in places, understanding new farmers’ migration experiences is a critical juncture for the LFM since the creation of a sense of place is expected to influence not only who goes, who stays, but may also offer possible explanations as to why.

Conceptualizing sense of place

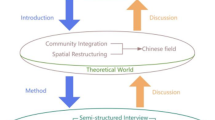

A tripartite approach consisting of place identity, place attachment, and sense of community was developed to examine new farmers’ sense of place construction. The framework used here presents a slightly different approach to understanding sense of place (see Fig. 1) that builds on Gustafson’s (2001) self-others-environment model and also incorporates the physical and social dimensions of place as emphasized by Nielsen-Pincus et al. (2010) and Scannell and Gifford (2010) who demonstrated the value of differentiating dimensions of place.

For the purpose of this research, it did not seem appropriate to adopt one particular framework. Nielsen-Pincus et al. (2010) focused on the individual’s relationship to the physical dimensions of place in terms of identity, attachment, and dependency. This research extends this work as it is equally interested in new farmers’ experiences navigating the social environment. Scannell and Gifford’s (2010) person-process-place framework highlights an integrative approach to place research. However the focus on people–place relations as “…manifested through affective, cognitive, and behavioral psychological processes” underscores an environmental psychological directive, which is effectively outside the scope of this research. Gustafson’s (2001) framework provides a structured, yet fluid approach to understanding place where “the meaning of place are not forced into three discrete categories but mapped around and between the three poles of self, other, and environment” (quoted in Smaldone et al. 2005, p. 398). But as Pretty et al. (2003, p. 273) have pointed out, it is by clarifying operational definitions and differentiating terms from each other that make it possible to “explore the distinctiveness of, and the relationship between, sense of place dimensions.” Thus the aim of this section is to build on these previous approaches and provide a clear description of the framework.

First, sense of place is explicitly conceptualized based on two key principles. As shown on the y-axis of Fig. 1, place can take the form of a physical environment to that of a more social nature. The x-axis represents how people can experience places as individuals and as a part of a collective (Agnew 2005; Cresswell 2004, 2009). Based on these coordinates, place identity (self), place attachment (the environment), and sense of community (others) emerge as key concepts to help facilitate an examination of new farmers’ experiences across the physical-social landscape and the individual-collective continuum.

Here, place identity refers to how individuals use the environment to situate their identity (Cuba and Hummon 1993; Nielsen-Pincus et al. 2010). For example, studies have shown that a place of residence (e.g., neighborhoods) can reveal one’s tastes, interests, priorities, or be seen as a social commentary about one’s stage in life, social status, and so on (Lappegard and Kolstad 2007). For these reasons, some researchers see place identity as a form of place attachment due to the symbolic importance of the physical environment in defining oneself (see Stedman 2003). In this study, however, we want to distinguish the term place attachment to mean the emotional bond (positive or negative) that develops between people and their physical landscape (Manzo 2005). In other words, place identity is a question of what does this place mean to the individual whereas place attachment details the experiences attributed to a particular physical environment. To address the social landscape, the concept of a “sense of community” is integrated into the framework and calls attention to how new farmers develop social attachments in the communities they live and work in. Drawing on McMillan and Chavis (1986, p. 9), a sense of community describes, “…a feeling that members matter to one another and to the group, and a shared faith that members’ needs will be met through their commitment to be together.”

Research design

Study area and participants

This research is centered on the LFM in southern Ontario, Canada. The study area was chosen because it is one of Canada’s most significant agricultural hubs, containing a high percentage of Class 1 arable land in Canada (Hofmann et al. 2005) and home to more than a quarter of Ontario’s farmers and their families (Statistics Canada 2011a). The area represents a spatially volatile region in which the urban–rural divide is both permeable and dynamic, and at the same time exhibits a high level of local food activity (Friedmann 2007; Donald 2008).

Participants were selected purposefully using snowballing, criterion, and opportunistic sampling strategies. Initial contact with potential participants began at the Ontario’s Test Kitchens: Cooking Up a Sustainable Food System for the 21st Century Conference held in Toronto, Ontario (April 2009). To be eligible for the study, new farmers had to self-identify as having no previous agricultural or rural background (i.e., they were not raised in a rural farming household or community), consider farming as their principle activity or profession, have no more than 5 years’ experience operating their farm, and be involved in a LFM. In total, nine new farmers living in five regions in southern Ontario were included in this study (see Fig. 2).

Study locations in southern Ontario, Canada. Source: Adapted from 2011 Census of Agriculture, Agriculture Division, Statistics Canada (2011b). Note: The inset map demarcates Census Sub-Divisions (CSDs) in southern Ontario. Field research was conducted in the following CSDs: CSD 16 (Kawartha Lakes), CSD 18 (Durham), CSD 23 (Wellington), CSD 41 (Bruce), and CSD 42 (Grey)

As summarized in Table 1, the nine farmers were highly variable and drawn to farming at various stages in life. Participants ranged from recent university graduates to a person approaching retirement. Just under half were married and a third had dependants while all reported having post-secondary education. With the exception of one farmer, those who owned farmland were older and married whereas younger, single farmers typically had land-sharing arrangements (see Table 2). The group tended to have smaller agricultural operations, used a variety of alternative farming practices, and most employed multiple marketing strategies. The majority did not report a steady off-farm income during the main growing season and only one-third consistently incorporated the use of on-farm help from hired laborers, interns, and volunteers. Pseudonyms are used in this paper to ensure research participants’ anonymity.

Methods and procedures

The sense of place framework supported the decision to undertake an ethnographic methodology because, as suggested by Pain (2004, p. 652), ethnography lends itself to support “research where people’s relations with and accounts of space, place, and environment are of central concern.” Thus, field research was essential to this study investigating peoples’ place-based constructions and experiences. Over the course of 10 weeks during July and August of 2009, Minh Ngo traveled to the following census sub-divisions (CSD) in southern Ontario: Bruce (CSD 41), Durham (CSD 18), Grey (CSD 42), Kawartha Lakes (CSD 16), and Wellington (CSD 23) regions (see Fig. 2). Whenever possible, she lived and worked with participants on their farm.

To explore the diverse dimensions of a sense of place, a singular data collection method seemed inadequate. In this respect, the sense of place framework influenced the decision to use a mixed methods approach that included semi-structured interviews, participatory photography (also known as photovoice) and participant observations to investigate a more nuanced sense of place.

Participants were entrusted with a digital camera to capture their thoughts and experiences of living and working in a rural community as new farmers. Participants were asked to take pictures to illustrate (1) what farming meant to them, (2) in what ways they felt supported, and (3) in what ways they felt challenged. This participatory photography method, popularized by Wang (Wang and Burris 1994; Wang et al. 2004) and further adapted by others (see Gotschi et al. 2009), enabled participants to generate data that enhanced their ability to communicate perspective. Coupled with photo-elicitation, the technique of combining photos with an interview has proven to be a useful process as “it gives detailed information about how informants see their world; and second, because it allows interviewees to reflect on things they do not usually think about” (Rose 2007, p. 243). As expressed by Hall (2009, p. 457), these photographs can expose elements of significance and provide important insight into how people see themselves and their environment. Further, a series of open-ended questions loosely structured around how new farmers made sense of who they are and the world around them in everyday spaces provided insights, opened up debates, and highlighted consensus and areas of conflict on pertinent issues. Though more strategic questioning was used towards the end of the field research to explore emerging themes, categories used for interpretation were not pre-determined prior to the data collection but generated through the process of data analysis.

Data processing and analysis

The data collection methods employed in this study produced a compilation of textual and visual data that were designed to provide insight into the “lived experience” (Atkinson and Hammersley 2010). In total, participants produced 210 photographs and approximately 20 h of taped interviews. All semi-structured and photo-elicitation interviews were audio recorded with the permission of the participants. The recordings were transcribed using an intelligent verbatim approach. Excessive use of “like,” “you know,” “ums,” and “ers” were excluded unless they had significance to the meaning. Photographs were stored as digital files and assigned to the corresponding participants.

The selected examples in Table 3 illustrate the process of moving from “raw data” collected in the field to more meaningful interpretations of how these new farmers developed their sense of place. The sense of place framework (as described in Fig. 1) provided an organizational structure to systematize data classification, guide the data analysis and facilitate an easier cross-referencing and comparison. As shown in Table 3, the first column clearly labels the three components of the sense of place accompanied by a brief statement of each key attribute (e.g., place identity is about how individuals see themselves through places). Following Creswell’s (2009) approach to qualitative data analysis, data were sorted and organized by creating basic descriptive units, developing thematic categories, and identifying patterns. Descriptive codes were assigned to various “pieces” of data (e.g., words, phrases, and images) and initially grouped according to which sense of place component it was most closely associated. Initial names of categories and topics were drawn from language used by the participant, but it took several iterations of data coding and categorization in order to develop a coherent sense of the new farmers’ diverse experiences and perspectives. The second column in the table identifies emergent topics within each sense of place component. The third column provides the specific visual and/or textual data and notes the source.

Given the complexity of this process, ensuring consistent interpretation across several participants was a key consideration. The mixed methods approach created ideal conditions for data triangulation whereby alignment of findings across various datasets could be used to assess its validity (Hay 2005). When land stewardship, for example, was identified as a motivating factor to farm during informal interviews, the triangulation approach allows for the search of evidence in the visual data to corroborate whether this particular value was also represented in the way these individuals pictured themselves as a part of the rural landscape. As it turns out, this analytical approach surfaced experiences, ideas, and perspectives that converged in some instances and diverged in others. Rather than seeing differences as a sign of insufficient evidence, England (2006, p. 291) suggests research exploring contested and constructed knowledge is uniquely positioned to provide space for differences “to be held in productive tension, and may keep our research sensitive to a range of questions and debates.” In this spirit, the next section in the paper presents an interpretation of the commonalities as well as differences among the new farmers’ sense of place development.

Results and analysis

Place identity

Rural landscapes linked to values and beliefs

New farmers exhibited a strong place identity rooted in rural landscapes, situating themselves within rural landscapes based on the desire to live their values, establish a connection with the natural world through meaningful work, and create a sense of community through the production of food. This resonates with the observation that the land and farm itself can often be a portrait of the farmer (Burton 2004) and how farming practices and identities can often be intertwined (Wilson et al. 2003). Here, current industrial farming practices were not seen as ideal and a key factor in deciding to farm began with a personal awareness about the importance of food production practices and its impact on society. Some talked about the role of agriculture in terms of community development while others highlighted its potential for civic engagement and economic reform. All, however, shared the opinion that there are severe environmental consequences from macro-scale industrial agriculture.

Interestingly, many held on to the principle of advocacy versus activism. While expressing concerns for the environment, they candidly talked about staying away from environmental activism because they did not want to “get caught up in the damage part,” thought the environmental movement was “kind of depressing,” “always about bad news,” or “fighting this or fighting that.” Instead, becoming involved in agriculture as a farmer was viewed with the possibility of doing something “positive,” “healing,” “proactive” for the environment and the community. As Gerald put it, “I was looking for a way to be alive on this planet and live my values.” Overall, farming was seen as an opportunity to “in a very small way, change the way things are.” Understandably, being able to “walk the talk” highlights the connection between new farmers’ sense of self and being placed in an environment where one is able to farm is significant. Elsie offers the photograph of her boots (Fig. 3) and her reflections on this photograph captures these broader views that links the construction of place identity to rural landscapes.

Walking the talk. Comment: Creation of Elsie’s place identity: “And so this picture is of my boots walking. My feet walking is the physicality of my life as a farmer…having a life that involves being outdoors and being active and having that integrated into what I do and who I am and connecting the mind and the body is really powerful.”

Confronting change

A nascent, but compelling dimension of this research suggests that being situated in a rural context can cause some new farmers to reassess their own values and beliefs. For instance, a few talked about the internal conflict they confronted when their profession as a farmer and rural location brought the reality of fossil fuel dependency closer to home. Nola took a picture of the license plate on her truck to signify her identity as a farmer but disclosed:

Yeah, it’s funny because it’s not really a part of—if I wasn’t a farmer I wouldn’t have a car like that. So that’s really a part of my identity as a farmer not really like my identity as Nola. That’s a big freaking truck; it guzzles gas and not good for the environment but a necessity and very practical for what I’m doing.

Likewise, Sarrah shared that she had to learn to drive, a considerable shift from her previous urban lifestyle that centered around alternative forms of transportation (e.g., walking, public transportation):

So one of the challenges of living in the country is you have to have a car and that was a huge step for me, to get a car. And also, it’s funny because I’m growing all my own food, and was like, wow, I’m so reliant on fossil fuel and it’s so much more apparent because I never had to fill up car with gas because I was always taking the bus or metro or walking everywhere [in the city]…

In a way, Sarrah’s experience simultaneously presents a challenge she associates with living in the country as well as an immediate adaptation to the environmental change. Another example of how new farmers reframe an understanding of themselves because of their place-based reality surfaced when Ethan photographed his truck. For him, it represented the materiality involved in creating a livelihood as a farmer once he moved to a small rural community. Having had initial beliefs against accruing consumer debt, he had to re-negotiate his ideals:

This is my truck and that’s a challenge in terms of the financial implications of buying a truck and having a van break down and owing people money for it until it’s paid off and the pinch in terms of the economics of starting a small business in agriculture without much capital is a challenge…Owing somebody else money, being in debt—that’s the most stressful because I’m not use to that. I’m used to much more freedom, not owing anybody anything like that.

The changing perspectives and evolving identities portrayed through pictures of farm vehicles are insightful as they capture the essence of how people–place relations drive change. This work supports earlier research findings that show, while people can change places, places have the capacity to alter people’s perceptions and behaviors (Stedman 2003). It underscores the significance of the relational dimension in place-making. These observations contribute additional evidence to suggest that places are being continuously constructed and re-constructed. Similar to Gombay (as cited in Feagan 2007, p. 35), this research holds that “places, scales, and identities ought to be understood not as discrete things but as events or processes that are embedded with one another and are in constant relationship, movement, and interaction.”

Place attachment

Experiences across the spectrum

New farmers transitioning into rural landscapes and livelihoods reported a mixture of affective and challenging feelings towards rural landscapes. Accompanied by a collection of photographs showing plants, open fields, animals (wild and domesticated), and other living creatures (e.g., insects), new farmers often point to the beauty, inspiration, and insights they gain from working on the farm and living in the countryside. As one farmer explains, “…everywhere I look, I see beauty and when I don’t see beauty I change.” In particular, when asked to describe what drew them to farming and rural spaces, new farmers quickly shared that being surrounded by nature made them feel “re-freshened,” “rejuvenated,” and “alive”.

An opinion held by all participants is the significance of being able to connect and work intimately with the natural world. A strong emphasis was placed on developing a relationship with the land. A photograph by Hannah of her “wedding rings” (Fig. 4) is representative of the deep connection new farmers felt towards the land and of being a part of an agricultural space.

Relationships with the land. Comment: Creation of Hannah’s place attachment: “Being a farmer means having a relationship with the land… this just means understanding your land and getting to know your land as if it was a person, so getting to know its mood, getting to know how to treat it, getting to know how it changes over the seasons and over the years. I find that there are only a few professions or types of work where you really develop a relationship with the land and I find that really rewarding so I took this picture because it is a picture of our wedding rings, which symbolize relationships, and they’re in the land.”

The experiential and relational dimensions of Hannah’s description resemble a humanistic concept of place where “[t]o know a place fully means both to understand it in an abstract way and to know it as one person knows another” (Tuan 1975, p. 152). In addition to the land, new farmers’ relationship with the rural environment included interactions with animals that may have otherwise been restricted in the city due to animal by-laws. Similar to developing and getting to know the characteristics of the land, new farmers who worked with animals spoke about getting to know their animals and adopting an alternative approach to agricultural animal-human relations. When asked to describe what farming meant to him, Chris shared,

These are animal friends. This is my pet Princess Cow, and I’ve enjoyed making friends with her, and I like the interaction between humans and non-human animals, especially pigs.

At the same time, several new farmers spoke about adjusting to the spatial realities of rural landscapes, noting the presence of feeling isolated as well as the constant need to drive in order to access basic amenities (e.g., banking, groceries, medical centers) and cultural or recreational opportunities. Coping mechanisms reported by some new farmers included regular trips to the city for a “city fix.” For those who could not get away, creative solutions helped to bring a bit of the city to the country (e.g., organizing a music concert on the farm). Overall, attachment to place is clearly conditioned in multiple ways that produce a range of experiences from comforting, to challenging, to constantly changing.

The influence of circumstance

Discerning commonalities among the challenges new farmers associated with the transition to rural environment proved difficult because challenges identified by one person would often be perceived as an opportunity by another. For instance, as a property owner, Hannah felt that winter was something to be endured saying that winter in the city is not like winter in the country “because there’s not a lot do in the winter I think you could get stir crazy.” Nola echoed these sentiments by further elaborating that the farm can be a social place during the growing season but when winter comes the physical isolation from others can be difficult:

Even if you’re living by yourself in the city it’s not hard to go out and be social with people. But when you’re living by yourself out here I find it very isolating. I don’t find it super healthy for me to be out here.

However, unlike Hannah, Nola was able to seek off-farm accommodation during the winter months. It was not necessary for her to stay on the farm because she was renting a few acres for vegetable production. Surprisingly Chris, another new farmer in a land-sharing agreement, offered a different perspective of winter. Instead of limiting his sense of mobility winter seemed to be a time for exploration:

I receive support from the winter time because it frees me up because you can see there’s no vegetables growing and the last winter I went out east and visited friends and family and this winter I’m going to go somewhere too…By not allowing me to grow vegetables, it supports my going away habits, and it encourages me not to stay.

Also, new farmers with families seemed better situated to discuss the positive attributes of the physical isolation more readily than their single colleagues. The reason for this was unclear, but one explanation may be connected to the stage in life. Yolanda, a mother of two young children, shared that as a result of being more isolated her family made more of an effort to participate in community events compared to when they lived in the city: “We probably do more community stuff now that we’re out here… In Toronto there’s tons and tons of entertainment going on all the time but we never went out. So this is, it’s good.” Elsie, a mother of three young children, found that moving to a rural community provided her family with an environment where they could deepen and strengthen their relationship with one another to a level that may not have been possible in the city:

I’ve often said how many forty-odd-year old women spend so much quality time with their seventy-odd-year old dad? And not just hanging out together but working on projects together, learning together, and being inspired together. Hearing my dad say, “Well I never thought I’d be telling my retired coffee club friends that I went out and helped my daughter buy a horse drawn manure spreader.”

The different ways in which individuals develop a rapport of the physical environment begins to suggest that new farmers’ place attachment is a discrete process contextualized by individual circumstances and the resources available to address situations as opportunities or challenges. The diverse experiences, impacts, and responses to physical isolation hints that place attachment may be differentiated along socio-demographic attributes. Overall these findings would support previous research that links this dimension of a sense of place to one’s stage in life at time of migration (Cuba and Hummon 1993).

Sense of community

Agricultural community of practices key to new farmers

A sense of community was mostly constructed from a diverse agricultural community of practice (ACoP) that shared an interest in what the new farmers were hoping to accomplish through farming. The four key components comprise their ACoP: customers, farming colleagues, family, and a broader community of interest (see Fig. 5).

Key components of new farmers’ sense of community. Notes: Creation of a sense of place comes from (a) customers who interact directly with farmers and invest in the farming initiative, (b) farming colleagues who provide professional and social opportunities, (c) family members who contribute to emotional, financial, and operational support, and (d) communities of interest that diversify networks and strengthen LFM goals

Customers were central to new farmers’ sense of community. This is especially true for new farmers engaged in a community supported agriculture (CSA) model. For instance, Nola provided a photograph of a washing table that one of her customers built in exchange for a CSA membership. To Nola, the table represents how she and her CSA community can support each other to include “…finding different ways to work with people if they don’t have enough money to pay you for a share.” Not surprisingly, farming colleagues were identified as fundamental to their community of practice. Conversations about the importance of colleagues were often linked to organizations such as the Ecological Farmers Association of Ontario (EFAO), Collaborative Regional Alliance for Farmer Training (CRAFT), and Stewards of Irreplaceable Land (SOIL) who brought like-minded individuals together socially and professionally by facilitating learning exchanges and networking opportunities.

While the inclusion of family members as a part of new farmers’ sense of community was anticipated, they made clear that family members provided not only emotional support but also significant operational and financial assistance. Many younger farmers acknowledged the significance of having parents who were able to offer loans for mortgages, farm equipment, and sometimes an “open-door” policy during winter months. New farmers who were married stressed the importance of having a partner who believed in and shared the farm vision. For example Elsie, whose family had an established life and community in the city, underscored that it would have been impossible to farm without a partner who was “willing to support that and take that risk and do something he’s never considered before.”

Perhaps one of the most surprising components of new farmers’ sense of community was the inclusion of a broader community of interest. This was best captured with a photograph of a bookshelf by Yolanda to illustrate the importance of being able to identify with past and present back-to-the-land and sustainable agriculture movements. To her it meant, “…it’s out there, that I’m not on my own.” Furthermore, the participants took photographs of the researcher to illustrate that connecting to a broader community of interest was an opportunity to mediate social isolation. More importantly, it was a means to be involved in the production of knowledge that could help inform and advance the goals of the LFM.

Urban and rural dynamics

With the exception of a few helpful neighbors, new farmers’ sense of community seemed geographically dispersed since relationships were often developed with people residing outside their own rural municipalities. One possible explanation for this might be that urban cities tend to provide more market opportunities for alternative food initiatives (Jarosz 2008). At the same time, the farmers in this study clearly expressed the desire to cultivate a sense of community around food and agriculture with individuals living in urban environments. As Annie puts it:

…one of the key things about being out here is that I just want people to come out here and visit…There are so many people with no knowledge of growing things or farming or food security or about the labor requirement for organic vegetables and that sort of things…

The urban focus may be a reflection of their own experiences prior to farming when they felt removed from the realities of agriculture. Not surprisingly, new farmers saw the need to provide a direct agricultural link for people living in cities. Interestingly while creating a sense of community around food and agriculture was identified as a significant motivation for new farmers’ urban–rural migration, developing a sense of community with the local community appeared to be more challenging. Perceived cultural and professional differences seem to socially distance them from their immediate community. Social differences between veteran rural residents and counter-urbanites have been documented (see Mitchell and Bryant 2009; Jones et al. 2003; Marshall and Foster 2002) however the situation for these new farmers may have been compounded by their decision to participate in LFMs. One farmer explains the situation as this:

I want to be on good terms with everybody but I don’t need to be a part of the community. I mean I kind of want to be a part of the organic community—which isn’t a local type thing—but as far as our neighbors go, we have different tastes, different interests, and different cultures.

Although LFMs are gaining visibility, industrial agriculture still dominates much of the agricultural landscape in Canada. At an institutional level, the majority of new farmers commented feeling somewhat out-of-place and believed systematic barriers in the current industrial food system make it difficult for new farmers to succeed. At the local level, Chris, a younger new farmer shared that some people were not shy in expressing their opinions of him “playing farmer”:

I mean, even people who have done tractor work for me, will say it outright, like you’re not really a farmer, or you’re not a true Canadian farmer, backyard gardener, these sorts of things, hobby farmer, city official. It makes it, I don’t know, it’s not the best.

Overall, it appears that new farmers have a strong sense of community rooted within their own networks. The majority of the farmers demonstrated the ability to connect with some people in their local community and described a positive, or at least, a working relationship with neighbors. However, integration into the immediate and the greater agricultural community did not appear to take precedence and remained a challenge for most.

Discussion

New farmers’ sense of place differs from earlier back-to-the-landers

At first glance the new farmers participating in this study could be easily described as a new generation of the back-to-the-landers. Indeed, strong similarities can be drawn between the new farmers and the back-to-the-landers of the 1960s/1970s in their shared pursuit to be closer to nature and the counter-cultural practices that is reminiscent of a “youth-centered and directed cluster of interest and practices around green radicalism, direct action politics” (Halfacree 2006, p. 313). However, a closer examination of what shapes new farmers’ sense of place reveals that they may be slightly different in that they were not purely driven by a desire to escape the city.

On the contrary, the results of this study indicate their place identity and attachment to rural places included an earnest desire to remain connected to the city and cultivate a sense of community with the urban population. While the desire to farm resulted in these new farmers moving to rural spaces, it did not mean that they were “opting out of society” because farming was seen as an opportunity to facilitate and encourage meaningful rural–urban interactions. New farmers’ enthusiasm to bridge the rural–urban divide reinforces Halfacree’s (2007, p. 5) observation that a strand of the back-to-the-landers today has “little desire to drop out of society or isolate themselves.” For scholars who have been critical of the LFM’s focus on produce and production, these new farmers demonstrate that there are people willing to make significant changes in their lives to “re-connect to context—to the soil, to work (labor), to history, or to place” (DeLind 2011, p. 279, my emphasis).

New farmers’ sense of place contests urban–rural binaries

The nimbleness in which the new farmers negotiate rural and urban relationships to reconstruct their place identity, place attachment, and sense of community supports the idea of shifting mobilities among contemporary urban–rural migrants blurring traditional boundaries (Milbourne 2007). Urban–rural migrants are typically classified into groups based on their motivations, economic and environmental ties to the community of origin and destination. As outlined by Mitchell (2004), exurbanites tend to describe people who retain employment ties in their larger community of origin and migrate to a smaller town based predominately on the rural appeal. Displaced urbanites are on the opposite end of exurbanites because they often move out of economic necessity (e.g., lower living cost, employment). Lastly, individuals who sever employment ties with the community of origin and relocate to pursue a livelihood and lifestyle in a rural environment are said to be anti-urbanites.

Interestingly, the new farmers in this study could arguably take on characteristics of all three in the way they define who they are, their purpose and experiences. They could be considered as ruralites because of severed employment ties with the community of origin; yet their continued emotional and economic ties with urban centers suggest qualities of an exurbanite. Also, one could potentially argue that they are displaced urbanites pushed into the hinterland due to agricultural zoning by-laws. In this respect, new farmers’ sense of place development offers support for a more complex understanding of the counter-urbanization movement and adds to a growing body of research demonstrating that the urban–rural migration phenomenon is far from homogenous (Escribano 2007).

New farmers’ sense of place reflect socio-spatial challenges

In contrast to the dominant imagery of timeless, unchanging countrysides (Agyeman and Neal 2009), the presence of new farmers in rural farming settlements shows the rural as a contested space. It is open to reflecting the values, imaginaries, and mobilities of a shifting demographic. These changes however are not without incidence. On the one hand, new farmers—as urban–rural migrants, may be perceived as valuable resources to help revitalize aging and sometimes struggling rural communities (Paniagua 2002; Mitchell 2004; Stockdale 2006). Alternatively, these new farmers may be seen as a part of on-going urbanization processes eroding a certain rural sense of place and way of life (Masuda and Garvin 2008). This view is similar to other urban–rural migration research that have concluded new migrants may encounter social isolation, or even animosity, from more established rural residents who associate them with urban encroachment and rural gentrification (Walker 2000; Phillips 2010).

With respect to agriculture, there have been reports of tension between industrial and alternative forms of agriculture (e.g., organic farming) where the latter is perceived to be a threat to traditional rural values (Padel 2001). Thus, one can see how the arrival of new farmers involved in the LFM might fuel the debate about who “belongs” where. In a case study examining the social network structures of new farmers with and without rural backgrounds in France, Mailfert (2007) reported that “neo-farmers” (i.e., those new to farming) struggled to be seen as “proper” farmers. As a result, the neo-farmers had weak connections in their local community and found it extremely hard to mobilize material and informational resources to support their new farm start-ups.

The French’s strong terroir traditions may have exacerbated the situation in this case; nevertheless it demonstrates how being perceived as an “outsider” can impact how new farmers embed themselves into rural communities where farming traditions run deep. This research underscores the importance of situating new farmers as a part of a broader place-making process where a sense of place can shape socio-spatial relations that form identities, differentiate social cohesion, and influence the dynamics of community life (Foote and Azaryahu 2009). This would certainly help explain why new farmers in this study exhibited a strong sense of community with other LFM groups and relatively weaker ones with those who live in their immediate neighbourhood.

Although Jones et al. (2003) note that people moving to the countryside quickly feel out-of-place when expectations are unmet, this did not appear to be the case for the new farmers participating in the study. Reasons remain unclear, but one possible explanation is as new comers to the community and agricultural profession these new farmers were in the formative stages of building social ties and managed their expectations accordingly. Another interpretation is that unlike counter-urbanites who relocate for rural amenities (e.g., more green space, less violence, a good place to raise children, a better sense of community and so on), new farmers’ connection to rural landscapes went beyond a place of residence. Their sense of place seems rooted in a deep reverence for the land. The rural environment transformed into a place where they, as individuals, could actively address concerns about the environment and economy through the practice of agriculture.

A strong place identity grounded in the land, coupled with a diversified ACoP that included places and people once considered linked but tangential to traditional farming communities (i.e., the urban community) may have allowed these new farmers to moderate the social distance between them and their immediate community. Interestingly, this adaptation raises critical questions about the impact of having people who share a common space but lack a sense of connectivity. Social researchers Manzo and Perkins (2006) seem to suggest a sense of place where the nature and quality of interpersonal relationships between the communities within a place are ignored, or vacant, point to larger socio-spatial politics at play. The impact, they argue, affects “whether we feel marginalized or empowered to participate in community change efforts, and whether we feel we have a place, or a right to a place, at the bargaining table” (Manzo and Perkins 2006, p. 340).

Conclusion

Undergoing a substantial shift in lifestyle and employment, new farmers involved in the LFM are in a state of transition. These transitions can be compounded during these complex periods that are characterized by “between belongings” (Marshall and Foster 2002) and challenge one’s sense of attachment to both the people and places that ultimately define a sense of place.

The empirical component of this research is based on an intensive 10-week field season in 2009 that explored the day-to-day lives of nine individuals new to the rural farming landscape. As with the case of most emergent research, the claims of this study need to be considered in light of the small number of participants. Nonetheless, this study has advanced our understanding of a new generation of back-to-the-landers redefining their sense of place. Specifically, it revealed that new farmers create a highly dynamic sense of place consisting of rural and urban connections to re-situate themselves within rural farming communities. The study also found that although new farmers shared a common goal to be a part of rural and agricultural landscapes, individual circumstances shaped by priorities, assets, and resources seemed to facilitate different experiences of places. Thus, sense of place development among these new farmers was an uneven, differentiated process.

This research highlighted the transition for individuals entering the farming profession to be characterized by much more than the acquisition of production and business competencies. New farmers have to navigate the social landscape. Current discussions around new farmer development tend to focus on technical skills, but support on and off the field requires consideration. For example, the new farmers indicated that an ACoP is a place where they draw strength, inspiration and motivation. Given that the ACoP plays such an integral part in constructing their sense of place, LFM practitioners may want to look into developing strategies that enhance connectivity and opportunities for networking and reciprocal learning exchanges sensitive to different needs. The sense of place framework in Fig. 1 facilitated a systematic assessment of how emergent farmers define their sense of belonging. It allowed the research to look beyond the technical skills of farming and it shone a light on the complexity of building a sense of place. By framing the issues across social-physical and individual-collective dimensions, it helped identify the differentiated importance of attachment, identity, and community in place building processes.

This preliminary examination into the social dimensions of new farmers’ sense of place calls attention to the dynamics between the industrial farming community and new farmers involved in the LFM. An “us” versus “them” mentality may offer the path of least resistance; however, the future of these various agricultural actors are intricately linked through the space they share. It would seem that there is an opportunity to engage different members of the rural farming community in the LFM conversations. This would not necessarily be about finding a united voice but more about moving across boundaries, finding commonalities, and pioneering collaborations that have the potential to strengthen the resiliency of rural communities as a whole. This study did not investigate perspectives from the entire spectrum of rural populations; but if the growth in LFMs is to move forward, a better understanding of interactions across rural actors and perceptions of new people entering the agricultural profession and community warrants further investigation. After all, if new farmers are being encouraged to become a part of the rural agricultural landscape, the LFM stands to benefit from engendering the politics of place as a people movement rather than simply a food movement.

Notes

For more information on these initiatives, refer to the following websites: (1) www.farmstart.ca, (2) www.justfood.ca, (3) www.ubcfarm.ubc.ca/teaching-learning/practicum, and (4) www.kwantlen.ca/ish/RFS.html.

References

Agnew, J. 2005. Space: place. In Spaces of geographical thought: deconstructing human geography’s binaries, ed. P. Cloke, and R. Johnson, 81–96. London, UK: Sage Publications.

Agyeman J., and S. Neal. 2009. Rural identity and otherness. In The encyclopedia of human geography, 277–281. Oxford, UK: Elsevier.

Atkinson, P., and M. Hammersley. 2010. Ethnography principles in practice. London, UK: Taylor and Francis Ltd.

Born, B., and M. Purcell. 2006. Avoiding the local food trap: scale and food systems in planning research. Planning Education and Research 26(2): 195–207.

Burton, R. 2004. Seeing through the “good farmer’s” eyes: towards developing an understanding of the social symbolic value of “productivist” behavior. Sociologia Ruralis 44(2): 195–215.

Cheng, A.S., L.E. Kruger, and S.E. Daniels. 2003. “Place” as an integrating concept in natural resource politics: propositions for a social science research agenda. Society and Natural Resources 10(2): 195–209.

Creswell, J. 2009. Research design: qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches, 3rd ed. Los Angeles, US: Sage Publications.

Cresswell, T. 2009. Place. In The international encyclopedia of human geography, ed. R. Kitchin, and N. Thrift, 169–177. Amsterdam, NL: Elsevier.

Cresswell, T. 2004. Place: a short introduction. London, UK: Blackwell.

Cuba, L., and D. Hummon. 1993. Constructing a sense of home: place affiliation and migration across the life cycle. Sociological Forum 8(4): 547–572.

DeLind, L. 2011. Are local food and the local food movement taking us where we want to go? Or are we hitching our wagons to the wrong stars? Agriculture and Human Values 28(2): 273–283.

DeLind, L. 2006. Of bodies, place, and culture: re-situating local food. Agricultural and Environmental Ethics 19(2): 121–146.

Dempsey, N., G. Bramley, S. Power, and C. Brown. 2011. The social dimension of sustainable development: defining urban social sustainability. Sustainable Development 19(5): 289–300.

Desjardins, E., R. MacRae, and T. Schumillas. 2010. Linking future population food requirements for health with local production in Waterloo Region, Canada. Agriculture and Human Values 27(2): 129–140.

Donald, B. 2008. Food system planning and sustainable cities and regions: the role of the firm in sustainable food capitalism. Regional Studies 42(9): 1251–1262.

DuPuis, E., and D. Goodman. 2005. Should we go “home” to eat?: toward a reflexive politics of localism. Journal of Rural Studies 21(3): 359–371.

England, K. 2006. Producing feminist geographies: Theory, methodologies and research strategies. In Approaches to human geography, ed. S. Aitken, and G. Valentine. London, UK: Sage Publications.

Escribano, M.J.R. 2007. Migration to rural Navarre: questioning the experience of counterurbanization. Tijdschrift voor economische en sociale geografie 98(1): 32–41.

Foote, K., and M. Azaryahu. 2009. Sense of place. In The international encyclopedia of human geography, ed. R. Kitchin, and N. Thrift, 96–100. London, UK: Elsevier.

Feagan, R. 2007. The place of food: Mapping out the “local” in the local food system. Progress of Human Geography 31(1): 23–42.

Friedmann, H. 2007. Scaling up: brining public institutions and food service corporations into the project for a local, sustainable food system in Ontario. Agriculture and Human Values 24(3): 389–398.

Gooch, M. 2003. A sense of place: ecological identity as a driver for catchment volunteering. Australian Journal on Volunteering 8(2): 23–33.

Gotschi, E., R. Delve, and B. Freyer. 2009. Participatory photography as a qualitative approach to obtain insights into farmer groups. Field Methods 21(3): 290–308.

Gustafson, P. 2001. Meanings of place: Everyday experience and theoretical conceptualizations. Journal of Environmental Psychology 21: 5–16.

Halfacree, K. 2006. From dropping out to leading on? British counter-cultural back-to-the-land in a changing rurality. Progress in Human Geography 30(3): 309–336.

Halfacree, K. 2007. Back-to-the-land in the twenty-first century—making connections with rurality. Tijdschrift voor economische en sociale geografie 98(1): 3–8.

Hall, T. 2009. The camera never lies? Photographic research methods in human geography. Geography in Higher Education 33(3): 453–462.

Hargreaves, A. 2004. Building communities of place: habitual movement around significant places. Housing and the Built Environment 19(1): 49–65.

Hay, I. 2005. Qualitative research methods in human geography, 2nd ed. Toronto, CA: Oxford University Press.

Hinrichs, C. 2007. Practice and place in remaking the food system. In Remaking the North American food system: strategies for sustainability, ed. C. Hinrichs, and T.A. Lyson, 1–15. Lincoln, US: University of Nebraska Press.

Hofmann, N., G. Filoso, and M. Schofiled. 2005. The loss of dependable agricultural land in Canada. Rural and Small Town Canada Analysis Bulletin 6(1). Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 21-006-XIE.

Jarosz, L. 2008. The city in the country: growing alternative food networks in metropolitan areas. Rural Studies 24(3): 231–244.

Jones, R., M. Fly, J. Talley, and K. Cordell. 2003. Green migration into rural America: The new frontier of environmentalism? Society and Natural Resources 16(3): 221–238.

Lappegard, H., and A. Kolstad. 2007. Dwelling as an express of identity: a comparative study among residents in high-priced and low-priced neighborhoods in Norway. Housing Theory and Society 24(4): 272–292.

Lewicka, M. 2005. Ways to make people active: The role of place attachment, cultural capital, and neighborhood ties. Environmental Psychology 25(4): 381–395.

Mailfert, K. 2007. New farmers and networks: how beginning farmers build social connections in France. Tijdschrift voor economische en sociale geografie 98(1): 21–31.

Manzo, L. 2005. For better or worse: exploring multiple dimensions of place meaning. Environmental Psychology 25(1): 67–86.

Manzo, L., and D. Perkins. 2006. Finding common ground: the importance of place attachment to community participation and planning. Planning Literature 20(4): 335–350.

Marshall, J., and N. Foster. 2002. Between belonging: habitus and the migration experience. The Canadian Geographer 46(1): 63–83.

Masuda, J., and T. Garvin. 2008. Whose heartland?: The politics of place in a rural-urban interface. Rural Studies 24(1): 112–123.

McMillan, D., and D. Chavis. 1986. Sense of community: A definition and theory. Community Psychology 14(1): 6–23.

Mendes, W. 2007. Negotiating a place for “sustainability” policies in municipal planning and governance: the role of scalar discourses and practices. Space and Polity 11(1): 95–119.

Milbourne, P. 2007. Re-populating rural studies: Migrations, movements, and mobilities. Rural Studies 23: 381–386.

Mitchell, C. 2004. Making sense of counterurbanization. Rural Studies 20(1): 15–34.

Mitchell, C., and C. Bryant. 2009. Counterurbanization. In The encyclopedia of human geography, ed. R. Kitchin, and N. Thrift, 319–324. Amsterdam, NL: Elsevier.

Mitchell, P., S. Hilts, J. Asselin, and B. Mausberg. 2007. Planting the first seed: creating opportunities for ethnic farmers and young farmers in the greenbelt. Report for the Friends of the Greenbelt Foundation Occasional Paper Series. Centre for Land and Water Stewardship, University of Guelph, CA. 25. http://greenbelt.ca/research/greenbelt-research/planting-first-seed-creating-opportunities-ethnic-and-young-farmers.

Nielsen-Pincus, M., H. Troy, J. Force, and J.D. Wulfhorst. 2010. Sociodemographic effects on place bonding. Environmental Psychology 30(4): 443–454.

Niewolny, K., and P. Lillard. 2010. Expanding the boundaries of beginning farmer training and program development: a review of contemporary initiatives to cultivate a new generation of American Farmers. Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development 1(1): 65–88.

Padel, S. 2001. Conversion to organic farming: a typical example of a diffusion of innovation? Sociologia Ruralis 41(1): 41–61.

Pain, R. 2004. Social geography: participatory research. Progress in Human Geography 28(5): 652–663.

Paniagua, A. 2002. Urban-rural migration, tourism entrepreneurs, and rural restructuring in Spain. Tourism Geographies 4(4): 349–371.

People’s Food Policy Project. 2011. Agricultural renewal final report. http://peoplesfoodpolicy.ca/newfarmersinitiative. Accessed on 10 March 2011.

Phillips, M. 2010. Counterurbanisation and rural gentrification: an exploration of the terms. Population, Space, and Place 16(6): 539–558.

Pretty, G., H. Chipuer, and P. Bramston. 2003. Sense of place among adolescents and adults in two rural Australian towns: The discriminating features of place attachment, sense of community, and place dependence in relation to place identity. Environmental Psychology 23(3): 273–287.

Rojas, A., W. Valley, B. Mansfield, E. Orrego, G. Chapman, and Y. Harlap. 2011. Toward food system sustainability through school food system change: think&EatGreen@School and the making of a community-university research alliance. Sustainability 3(5): 763–788.

Rose, G. 2007. Visual methodologies: an introduction to the interpretation of visual materials. London, UK: Sage Publications.

Scannell, L., and R. Gifford. 2010. Defining place attachment: a tripartite organizing framework. Environmental Psychology 30(1): 1–10.

Smaldone, D., C. Harris, and N. Sanyal. 2005. An exploration of place as a process: The case of Jackson Hole, WY. Environmental Psychology 25(4): 397–414.

Statistics Canada. 2011a. Census of agriculture 2011: snapshot of Canadian agriculture. http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/95-640-x/2012002/02-eng.htm#IV. Accessed 7 June 2011.

Statistics Canada. 2011b. Census of agriculture: map 1 Ontario 2011 census of agricultural regions and census divisions. http://www.statcan.gc.ca/ca-ra2011/110006-eng.htm. Accessed 14 September 2011.

Stedman, R. 2003. Is it really just a social construction?: the contribution of the physical environment to sense of place. Society and Natural Resources 16(8): 671–685.

Stedman, R. 1999. Sense of place as an indicator of community sustainability. The Forest Chronicle 75(5): 765–770.

Stockdale, A. 2006. Migration: pre-requisite for rural economic regeneration? Rural Studies 22(3): 354–366.

Tuan, Y. 1975. Place: An experiential perspective. Geographical Review 65(2): 148–155.

Walker, G. 2000. Urbanites creating new ruralities: reflections on social action and struggle in the greater Toronto area. The Great Lakes Geographers 7(2): 106–118.

Wang, C., and M.A. Burris. 1994. Empowerment through photo novella: portraits of participation. Health Education and Behavior 21(2): 171–186.

Wang, C., S. Morrel-Samuels, P.M. Hutchison, L. Bell, and R.M. Pestronk. 2004. Flint photovoice: community building among youths, adults, and policymakers. American Journal of Public Health 94(6): 911–913.

Wilson, D., M. Urban, M. Graves, and D. Morrison. 2003. Beyond the economic: farmer practices and identities in central Illinois, USA. The Great Lakes Geographer 10(1): 21–33.

Winter, M. 2003. Geographies of food: agro-food geographies-making reconnections. Progress in Human Geography 27(4): 505–513.

Acknowledgments

This paper benefited from Fiona Mackenzie’s contributions to the original research design. Two anonymous reviewers helped sharpen the paper’s focus and provided several suggestions that improved overall clarity. This research would have not been possible without the unselfish collaborations of new farmers in southern Ontario.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ngo, M., Brklacich, M. New farmers’ efforts to create a sense of place in rural communities: insights from southern Ontario, Canada. Agric Hum Values 31, 53–67 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-013-9447-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-013-9447-5