Abstract

This paper analyses the interference of three socio-demographic characteristics: gender, age and migration status on the labour market outcomes from the perspective of intersectionality theory. Concretely, we investigate whether gender and migration differences in hourly wages are observable at younger ages and whether these differences increase with age. Further, we analyse whether gender and migration interact in such a way that women with migration background suffer lower wage growth in relation to their counterparts. Our analyses draw on data from the Socio-Economic Panel (German SOEP from 1991 to 2014), distinguishing between populations with and without a migration background. Random effects hourly wage regressions controlling for selection bias using Heckman procedure have been estimated in our analysis. The results show that there are large gender differences in hourly wage at younger ages, and these differences are maintained over the life course. Regarding migration status, no significant disadvantages in wages are observable at early stages. However, disadvantages of men and women with migration background increase with age, resulting in lower earnings for older workers with migration background. When we analyse the interaction between migration and gender, we observe no effect either at younger ages or over the entire lifespan, indicating that the gender disadvantage is no more pronounced for women with migration background than for women without such a background (and vice versa).

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The European Union’s shrinking labour force has alerted politicians and policy makers to the need to address the challenges posed by today’s ageing workforce. The status of older workers in contemporary labour markets is highly dynamic and depends very strongly on economic sector, workers’ socio-demographic characteristics, the economic situation in the given country and the structure of local welfare and retirement systems (Hofaecker 2010). Besides, Europe’s ageing workers are quite a heterogeneous group, in which differences in ethnic origin, race, gender, religious beliefs, sexual orientation, physical abilities or other minority statusFootnote 1 can position individuals very differently within employment structures (Ainsworth and Hardy 2007). In addition, increasing migration continues to broaden the diversity of European populations, bringing with it even a greater variety of experiences, barriers and opportunities in the labour market. In light of this trend, it is important to understand the mechanisms that explain increasing inequalities over the life courses of members of different social groups.

In this paper we investigate the interaction between three factors that influence an individual’s socio-demographic status—namely, age, gender and migration background—in order to identify whether these statuses contribute to negative outcomes in the labour market—in our case in relation to wages. Wage differences are the result of a variety of factors, of which discrimination may provide one explanation, but such differences may also be attributable to variances in productivity among older workers (Myck 2015; Belloni and Villosio 2015). The paper also addresses how individuals accumulate certain advantages and disadvantages over their individual life courses as a function of the socio-demographic characteristics attributable to them.

Our analysis draws on data from the Socio-Economic Panel (German SOEP) from 1991 to 2014, distinguishing between populations with and without a migration background, and addresses the following questions: Are there any significant differences in hourly wages of younger workers with a migration background as compared to younger workers without such a background? Can any gender differences be observed in these outcomes? Do such effects show any interaction with each other? And, do these differences tend to increase as workers get older?

We have decided to concentrate specifically on the baby boom cohort, both because of their demographic relevance and because their entire employment biographies are available, as members of the cohort are now in or reaching their 60 s. Aside from this, they entered the labour market after a period of significant expansion in educational opportunities (Simonson et al. 2014), and at a time of rapidly increasing diversity in the labour force due to a large-scale influx of economic migrants (Gastarbeitern) in the 1950s and 1960s. Both of these phenomena have led to significant changes in the structure of the labour force and have had a substantial effect on the working biographies of baby boomers (Diewald et al. 2006).

Germany provides an interesting case for the study of differential labour market outcomes for older workers with contrasting migration statuses, since it faces a future in which the number of migrant workers is likely to increase. In 2014, the share of population aged 65 and over with a migration background was around 9% (Statistisches Bundesamt 2015). However, about 38% of the total population of Germans with a migration background are now between 20 and 45 years old, while the same age group currently accounts for only 29% of the population without any migration background. As these cohorts grow older, the share of older individuals with a migration background is set to rise substantially, with potentially important effects, not only for the country’s demographics, but also for its cultural, social and economic landscape. This trend will also be intensified by the migration events of 2015 and 2016, the effects of which cannot yet be quantified, but will surely bring a substantial increase in diversity among the German population.

Theoretical background

The theoretical background of the paper draws upon two perspectives. First is the concept of intersectionality, a widely recognised research perspective adopted by feminist scholars, political advocates of equality (Crenshaw 1991; Nash 2008; Burman 2003) and by researchers in the field of gerontology (Moore 2009; Calasanti 2004; Mcmullin 2000) alike. Second, we employ the perspective of “cumulative advantage and disadvantage” (or CAD) (DiPrete and Eirich 2006; Dannefer 2003; Walsemann et al. 2008) to explain the unequal outcomes in the labour market performances of different social groups. This approach not only allows us to consider the heterogeneity of older workers, it also makes it possible for us to take the age heterogeneity of migrants into account, thus revealing unequal status between these various subgroups, an aspect of the topic that is all too often missing from the public debate.

Intersection of gender, age and migration status

The concept of intersectionality developed from the observation that gender and race tend to converge and they produce a state of multiple disadvantage that cannot be properly understood by analysing the two statuses separately. Crenshaw claims that the experiences of people who are subject to more than one disadvantaged status simultaneously are utterly unique and, therefore, no comparison to any single-status disparity can be justified, either for legal or for political application (Crenshaw 1991). Moreover, intersectionality operates between a variety of socio-demographic categories, including sex, race, ethnicity, class, sexual orientation, and it does so on many different levels. It is said to be an effect that is structurally carved into social institutions, creating a “conundrum of multiple oppressions” (Baer et al. 2010).

Intersectionality has also been deployed to analyse the interplay between two separate disadvantaged statuses in employment and the way they influence an individual’s career chances. Evidence of a gender penalty on earnings is now well-established in sociological and economic literature (Tijdens and van Klaveren 2012; Grönlund and Magnusson 2013; Chang 2010) and needs no reiteration here. Similarly, the negative impact on the earnings of women due to their ethnic or racial minority status has also been established in a number of studies (Barnum et al. 1995; Greenman and Xie 2008; Xu and Leffler 1992), providing empirical evidence to support a “double jeopardy” hypothesis, which asserts that simultaneous membership of two underprivileged groups will have an additive effect, and even a “triple jeopardy” situation if yet other statuses are added to the mix (Macnicol 2005). However, as Greenman and Xie (2008) put it, there are also some indications that contradict this hypothesis, providing evidence that the gender penalty for minority women is actually smaller than for white women, and that the race penalty is smaller for women than for men, a combination of findings that suggests there is no additive effect between the two statuses (Macnicol 2005).

In gerontology, Vincent (1995) emphasised the importance of taking a step back from the mechanisms—based on gender and race—traditionally understood to produce social inequalities, and to incorporate age into the theoretical framework used in studying disadvantage. So far, the most commonly studied aspect of intersectionality in ageing studies has concerned the combination of age and gender (Woodward 2006; Duncan and Loretto 2004; Krekula 2007; Cotter et al. 2002). These categories were coupled with such minority statuses as ethnic origin or race in a study dedicated to analysis of the experiences that older women have in a variety of patterns of discrimination in employment (Moore 2009). It has been ascertained that older women experience barriers on re-entering the labour market and that their experiences will vary substantially depending on their ethnic origin and race. Aside from this, older women of minority backgrounds in self-employment have been shown to be discouraged from taking an entrepreneurial path in life through their constant confrontation with the normative white young male representation of the ideal entrepreneur (Ainsworth and Hardy 2007).

Intersectionality has also proved fruitful in migration research, which has long omitted the gender perspective, holding fast to the traditional idea of the man as the primary (economic) migrant, and treating women as no more than assisting partners (Bastia 2014). Studies on labour market outcomes reveal that when migrants hold several minority statuses at the same time, these statuses will tend to mutually reinforce each other, and will have a detrimental effect on their chances of promotion or equal wages (Lüdemann and Schwerdt 2013; Kreyenfeld and Konietzka 2002). There is also some empirical evidence pointing in the opposite direction, however, namely that migrant women enjoy an advantage over natives in terms of access to training and welfare assistance (Kynsilehto 2011).

Warnes and Williams (2006) suggest that analyses exploring the intersection between migration studies and gerontology have been around for decades. However, the focus of such research has generally been directed towards how the migration process itself affects people in older age groups, with the problems of already settled migrants receiving less attention. According to Vincent (1995), the migration status of ageing populations has always been considered an important dimension of inequality in old age, since it was accepted that early migration patterns strongly influenced the future life outcomes of such populations.

However, minority statuses and their potential for creating inequality in the labour market are not simply static functions that exert the same force throughout a person’s lifetime. Therefore, it is valuable to incorporate differences between age groups (i.e., cohort effects) and differences between various stages of life (age effects) into intersectional analyses of such comparatively static statuses as gender or migration background. For this reason, in order to incorporate a more dynamic perspective on the interrelation between the various axes of disadvantage, this paper includes a further theoretical perspective—namely the concept of cumulative advantage and disadvantage.

The accumulation of advantage and disadvantage throughout the life course

The main assumption of the theory of cumulative advantage and disadvantage (CAD) is reflected in the statement that the initial socio-economic advantage that a person may possess (in the form of capital and resources), accumulates throughout the life course and will tend to result in a position of greater advantage in later life. Similarly, a disadvantaged position in the early stages of life is likely to result in lower later socio-economic status. Patterns of inequality within and between cohorts will emerge over time as products of the interaction between institutional arrangements and individual life trajectories (O’Rand 1996). Factors that influence the growth of inequality are also determined by gender, race or migration background, and should therefore be analysed in the context of all these dimensions (DiPrete and Eirich 2006). Dannefer (2003: 327) describes cumulative advantage and/or disadvantage as “the systemic tendency for inter-individual divergence in a given characteristic (e.g., money, health, or status) with the passage of time”. He also proposed emphasising the general stratification mechanisms that differentiate between the various situations experienced by individuals within the same cohort, in contrast to what had been articulated by most demographic researchers up to then—i.e., a recommendation to measure inter-cohort differences, which contributed to the false assumption that there was strong homogeneity in intra-cohort experiences and outcomes (Dannefer 1987). One clear shortcoming of CAD theory is that it rarely pays attention to the heterogeneity of ageing populations in terms of such statuses as gender, ethnicity, disability or sexual orientation. These factors, as we commented earlier, are also of enormous importance in the emergence of inequalities in later life. CAD also overlooks the potential of resource mobilisation and human agency as critical factors in individual life trajectories, the impact of which is emphasised in the theory of Cumulative Inequalities (CI) as formulated by Ferraro and Shippee (2009).

In sum, three dimensions—age, gender and migration background—are vital considerations in reaching any understanding of the diverse outcomes experienced by different social groups in the labour market. Our analysis will attempt to show whether the mechanism of accumulation of advantages and disadvantages can be applied to studying the lasting effects of the intersection of age, gender and migration background. Previous research has suggested that widening the perspective to include such categories as ethnic origin, sexual orientation or nationality will further illuminate the complex power relationships relevant to the topic (Jyrkinen 2013).

Research questions and hypothesis

Based on the concepts described above, we will test the following hypotheses in our empirical analysis:

H1

Labour market differences between migrants and non-migrants can be observed in younger age groups.

From a CAD perspective, initial disadvantage will tend to translate into greater discrepancies between groups as they get older, an effect of great importance in how younger workers’ career paths develop. Among the most vivid examples of unequal starting points in the working careers of migrants as against non-migrants is the role of education, the effects of which are considerably stronger than all other initial disadvantages. On average, people with a migration background have much lower levels of educational attainment than their peers without migration background (Mollenkopf and Champeny 2009).

H2

These differences are larger for females than for males, to the extent that one may speak of an intersection between the two factors.

Our hypothesis suggests that the two factors—migration status and gender—interact to form a “double jeopardy” situation: that is to say, as the intersection of two disadvantaged statuses. The situation of women with a migration background can thus be expected to be worse than both the situation of non-migrant women and that of migrant males.

H3

Wages develop differentially as age advances for migrants compared to non-migrants, and for men compared to women.

The third hypothesis originates from CAD theory, according to which any initial privileged or disadvantaged situation of an individual will be magnified as his or her age advances, as particular forms of capital—both positive and negative—begin to accumulate unevenly throughout his or her life course. Thus, we can observe disproportionate inequalities among older individuals. According to the intersectionality approach, age is a third axis of inequality, which, added to gender and migration status, serves to form a tripartite pattern of intersecting disadvantage.

Empirical analysis

Data and sample selection

The analyses in this paper draw on data from the SOEP, which is a representative, interdisciplinary, longitudinal survey of the German population (Wagner et al. 2007). The panel started in 1984 and data are collected annually.

We concentrate for our analysis on the German baby boom generation—the cohort born between 1956 and 1965. This concentration on a single birth cohort (following Dannefer 2003) allows us to remove cohort effects from our analysis. Myck (2010) estimated age-wage profiles as separated by cohorts in order to disentangle cohort from age effects. He concluded that it would be misleading to neglect cohort-related factors and to simply assign their effects to the influence of age.

Our data set is made up of an unbalanced panel (that is to say: not all persons in the panel are consistently observable over the entire period studied) taken from survey waves between 1991 and 2014, in which information on the baby boomers is provided between the ages of 26–58. The total number of observations containing valid information on migration is 87,997, corresponding to 10,995 persons.

We make a distinction between populations with and without a “migration background” (Migrationshintergrund), a well-accepted concept in the German literature. Salentin (2014: 26) refers to this concept as “(…) a specifically German variant of the general sociological construct of foreignness, which describes a condition of perceived difference between groups as defined by cultural, geographical, biological, and/or linguistic criteria”. For the purposes of this analysis, however, the term “migration background” is taken to indicate simply that the relevant person him or herself has immigrated to Germany. Owing to limited space and observations, we do not extend our analysis to individuals of migrant origin but born in Germany.

Of the 10,995 persons in the panel, 8780 (80%) have no migration background and 2215 (20%) immigrated. Among the migrants, 22% are from Turkey, 13% are from Poland, 12% from Italy, 8% from Russia, 6% from the Ex-Yugoslavia and 6% from Greece (we do not list countries of origin for which the percentage is less than 6% of the total). The average amount of time since their arrival in Germany is 22 years. Table 1 describes the main characteristics of the sample.

Results

Labour market differences between migrants and non-migrants

We observe large percentages of young individuals with a migration background and with no (formal) vocational training (37.5% for women and 30.1% for men), while the corresponding percentages for the population with no migration background are much lower (11.2% for women and 10.2% for men). In addition, gender differences in these figures are larger among people with a migration background.

The question—apart from the effect on wages caused by differences in education and other wage determinants—is whether there is any additional effect exerted by having a migration background. In Table 2 we present wage regressions for young men and women separately (aged 26–30). We make our estimates for both men and women on the basis of three different models. In the first model we control only for migration background and age. We observe (without adding any further controls) a positive effect for both men and women of a migration background on hourly wages. This effect is larger for men than for women. This result remains when we add education as control variable (model 2). However, when we add controls for other important wage determinants (occupation, industry, tenure, self-employment, public sector status and work experience) the significance of the migration background effect disappears.

These results show differences between migrants and non-migrants at younger ages (in educational achievement, for example) but, after controlling for these characteristics, we find no significant effect of migration background on wages.

Gender differences

Based on a joint wage regression for men and women aged 26–30, we analyse whether there is any gender and/or migration background effect on earnings, and we then interact the two factors against each other to see if there is any intersectionality between them. We use a two-step Heckman model in order to minimise selection bias. Our first step was a probit estimation of labour participation with inclusion of the estimated inverse Mills ratio in the wage regression. We used the exclusion restriction procedure, in which additional meaningful variables are added to the probit of labour participation but not to the wage estimations. To be precise, health variables, number of children in the household, marital status, total income of the partner, and number of hours of housework by the partner were included in the labour participation estimation but not in the wage regression. The variables included in both models were gender, age, education, migration background, labour experience and region.

In Model (1) (Table 3), we estimated a wage regression model without interaction effects. What we learn from the estimation of this model is that, even after controlling for the main wage determinants, women are already earning less at younger ages (about 30% less, based on an hourly rate). However, we do not observe any significant effect of the migration factor on hourly wages (as already seen in Table 2). In this regression, we also observe that for the given age group there are no significant differences in earnings between the groups defined by educational achievement. At the same time, large differences in hourly wages are observable between East and West Germany. Holding all other independent variables constant, baby boomers in West Germany earned on average 38% more per hour than in East Germany. It should be emphasised that these wage figures correspond to the period from 1991 to 1995—shortly after German reunification, a time during which regional wage differentials were notoriously large (Franz and Steiner 2000). We also confirm the important role of selection in employment, which is reflected in the statistically significant coefficients for the inverse Mills ratios. The value of the effect is positive, indicating that the unobserved factors that make participation in the labour market more likely are associated with the prospect of higher wages. In other words, people who are observed to be in employment are more likely to have higher wages compared to a random sample.

In Model 2 (Table 3), we tested whether there is any intersectionality in outcomes between gender and migration background. The interaction term is not significant, thus allowing us to conclude that there is no intersectionality in negative wage outcomes between the factors of gender and migration status among younger age groups. That is, there does not appear to be any additive effect due to the interaction of the two factors.

Wage development

We ran hourly wage regressions for the age range of 26–58, employing a Heckman procedure here as well (Table 4). In the model that does not take interactions into account (Model 1) we see a large gender effect, showing that women earn on average 24% less per hour than men in the age group from 26 to 58. This observation shows that this gender effect occurs not only at younger ages (as one can see from Table 2), but it remains observable over the entire life course. We also find that people with a migration background earn, on average, 4% less than non-migrants do. This indicates that, while there are no significant differences in hourly wages between migrants and non-migrants at younger ages, differences begin to appear as the population gets older, with the result that individuals with a migration background earn slightly lower wages.

Living in West Germany, having higher levels of education, enjoying longer tenure and being employed in larger firms all also have a positive effect on hourly wages. Finally, we also observe that age has a positive effect, indicating that hourly earnings increase as people get older. Having experience of unemployment, doing part time work and being self-employed all have a negative effect on hourly wages. The coefficient of age squared is negative (albeit with only a small negative value), indicating that the positive effect of age becomes less pronounced as people get older.

We introduced first-order interaction effects into Model 2 in order to see whether the effects of gender and migration on wages accumulate as people get older. From the results of the interaction effects, we can confirm that wages of persons with migration background grow more slowly as they grow older than those of individuals with no such background, resulting in greater inequalities among older age groups.

However, we do not observe any age-related difference between the genders, meaning that—even if wages of women are much lower than those of men—they tend to increase at the same rate for both sexes as people get older. Furthermore, we observe no significant effect of interaction between gender and migration status. In light of this result, we can conclude that there is no intersectionality of negative outcomes on wages between gender and migration status. In the third model, in which we introduced second-order interaction, we see that the interaction between age, gender and migration background is not significant. This implies that wage development for migrants is not substantially affected by gender.

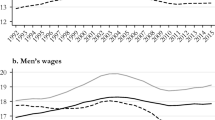

Figures 1 and 2 illustrate the predictive margins of gender and the corresponding confidence intervals for migrants (Fig. 1) and for non-migrants (Fig. 2). In both figures—for both migrants and non-migrants—we observe large (and significant) differences between men and women in predictive margins, an effect that is maintained across all age ranges. However, for migrants and non-migrants we observe differences in the development of predictive margins as people get older. While the predictive margins for non-migrants follow an inverse U form, the effect for migrants (both men and women) declines with age, reflecting the significance of the interaction effect of age and migration background.

Further analysis

We also ran all the models used in this study separately for the various different levels of educational achievement. The goal of this exercise was to test our results for heterogeneity between different educational groups. Both for individuals without vocational training and for individuals with higher education (i.e., university-level qualification), we find that migration has a similar effect (5% for those with the lowest level of education and 7% for the individuals with a third-level qualification), but detect larger gender effects for the less well-educated group (32%) than for the graduate group (21%). These results confirm that gender-based pay differences are more pronounced than migration-based differences, even when we consider a variety of different subgroups.

Finally, in order to check the data for people with a migration background for heterogeneity, we ran the model that included only migrants and controlled for the number of years since their arrival in Germany, as well as adding a dummy variable indicating whether the subjects are of Turkish origin or not (Turks were by far the largest migration group of our sample). Yet again we observe a large gender effect (17%). Further, the longer a person lived in Germany, the higher his or her hourly wage was likely to be. This indicates that the migration effect is mitigated at least to some extent by a longer stay in Germany. The variable ‘Turkish origin’ is not significant, indicating that there are no significant differences between Turkish migrants and people from other countries in relation to hourly wages after controlling for the main known wage determinants.

Summary and discussion

In the present paper, we tested three hypotheses: H1 Labour market differences between migrants and non-migrants can be observed in younger age groups; H2. These differences are larger for women than for men, to the extent that one may speak of an intersection between the two factors; and H3: Wages develop differentially as age advances for migrants as compared to non-migrants, and for men as compared to women.

The first hypothesis was not confirmed by our empirical analysis. The empirical literature shows that German residents—both men and women—with a migration background tend to have lower education levels on average than the general population (Riphahn 2003). Our results confirmed this insight. However, we did not find significant differences in hourly wages in younger age groups. The second hypothesis was not confirmed by our study either. We detected no intersectionality between the negative wage effects relating to gender and migration status among younger age groups.

The third hypothesis was confirmed in part. We found that differences in hourly wage as earned by migrants and non-migrants begin to appear as the population gets older, so that individuals with a migration background earn slightly lower wages on average. This result confirms the importance of introducing a life course perspective in our analyses, as suggested by Vincent (1995). It is possible that migrants may begin to encounter labour market barriers as they grow older, so that the pattern of evolution of their wages differs from that of people with no migration background. In contrast, wage differences between the genders do not increase with age: while women’s wages are already lower than those of men at younger ages, the differences do not grow as people grow older. Further, we observe no interaction effect between gender and migration over the life course.

To summarise, we found that large gender pay gap exists and remains constant over the life course and that pay gap between migrants and non-migrants begin to emerge with age. This suggests that there is a great deal of gender inequality in terms of hourly wages, an inequality which remains constant over the entire life course, and also a (less pronounced) inequality between migrants and non-migrants that increases with age. The results of our analysis did not provide evidence to suggest that the three statuses—age, gender and migration—interact in a way that might lead to older female migrants experiencing a sort of “triple jeopardy” in the labour market in relation to their wages. This scope of this study was limited to the topic of wages and did not analyse other dimensions of the experience of working life (such as the topic of promotions, interpersonal relationships, job opportunities, etc.), where discrimination may also occur.

We restrict our analysis in this study to a single birth cohort (i.e., the Baby Boomers) to allow us to identify the effects of age on wages in isolation from cohort effects. Of course, this restriction leaves us unable to investigate differences between cohorts. In further research, both age and cohort effects should be investigated in order to achieve a more complete picture of the age-wage relationship and how it evolves over time.

Distinctions between the varying employment biographies and contrasting employment situations of older individuals are of great relevance to our analysis. An improved knowledge of the cumulative and intersectional mechanisms that produce these differences would greatly help to address the problem of disadvantage at earlier stages in the biographies of those affected by such disadvantage, and may ultimately contribute to reducing inequalities among older workers.

Notes

The understanding of minority status adopted in this paper follows the definition by Wirth (1945) who identified a minority group as “any group of people who, because of their physical or cultural characteristics, are singled out from the others in the society in which they live for differential and unequal treatment, and who therefore regard themselves as objects of collective discrimination”. Thus, despite what the name suggests, the identification of these groups as having “minority” status is thus related to their disadvantaged position in society, and has no connection with the size of the group.

References

Ainsworth S, Hardy C (2007) The construction of the older worker: privilege, paradox and policy. Discourse Commun 1(3):267–285

Baer PS, Bittner M, Göttsche AL (2010) Mehrdimensionale Diskriminierung—Begriffe, Theorien und juristische Analyse (Multidimensional discrimination—concepts, theories and legal analysis). Antidiskriminierungsstelle des Bundes, Berlin

Barnum P, Liden RC, Ditomaso N (1995) Double jeopardy for women and minorities: pay differences with age. Acad Manage J 38(3):863–880

Bastia T (2014) Intersectionality, migration and development. Prog Dev Stud 14(3):237–248

Belloni M, Villosio C (2015) Training and wages of older workers in Europe. Eur J Ageing 12(1):7–16. doi:10.1007/s10433-014-0327-7

Burman E (2003) From difference to intersectionality: challenges and resources. Eur J Psychother Couns 6(4):293–308

Calasanti T (2004) Feminist gerontology and old men. J Gerontol Ser B 59(6):305–314

Chang ML (2010) Shortchanged: why women have less wealth and what can be done about it. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Cotter D, Hermsen JM, Vanneman R (2002) Gendered opportunities for work: effects on employment in later life. Res Aging 24(6):600–629

Crenshaw K (1991) Mapping the margins: intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanf Law Rev 43(6):1241–1299

Dannefer D (1987) Aging as intracohort differentiation- accentuation, the Matthew effect, and the life course. Sociol Forum 2(2):211–236

Dannefer D (2003) Cumulative advantage/disadvantage and the life course: cross-fertilizing age and social science theory. J Gerontol Ser B 58(6):327–337

Diewald M, Goedicke A, Mayer KU (2006) After the fall of the wall: life courses in the transformation of East Germany. Stanford University Press, Stanford

DiPrete TA, Eirich GM (2006) Cumulative advantage as a mechanism for inequality: a review of theoretical and empirical developments. Annu Rev Sociol 32(1):271–297

Duncan C, Loretto W (2004) Never the right age? Gender and age-based discrimination in employment. Gend Work Organ 11(1):95–115

Ferraro KF, Shippee TP (2009) Aging and cumulative inequality: how does inequality get under the skin? Gerontologist 49(3):333–343

Franz W, Steiner V (2000) Wages in the East German transition process—facts and explanations. Ger Econ Rev 1(2):241–270

Greenman E, Xie Y (2008) Double jeopardy? The interaction of gender and race on earnings in the United States. Soc Forces 86(3):1217–1244

Grönlund A, Magnusson C (2013) Devaluation, crowding or skill specificity? Exploring the mechanisms behind the lower wages in female professions. Soc Sci Res 42(4):1006–1017

Hofaecker D (2010) Older workers in a globalizing world. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham

Jyrkinen M (2013) Women managers, careers and gendered ageism. Scand J Manag 30(2):175–185

Krekula C (2007) The intersection of age and gender: reworking gender theory and social gerontology. Curr Sociol 55(2):155–171

Kreyenfeld M, Konietzka D (2002) The performance of migrants in occupational labour markets. Eur Soc 4(1):53–78

Kynsilehto A (2011) Negotiating intersectionality in highly educated migrant Maghrebi women’s life stories. Environ Plann A 43(7):1547–1561

Lüdemann E, Schwerdt G (2013) Migration background and educational tracking: is there a double disadvantage for second-generation immigrants? J Popul Econ 26(2):455–481

Macnicol J (2005) The age discrimination debate in Britain: from the 1930s to the present. Soc Pol Soc 4(3):295–302

Mcmullin J (2000) Diversity and the state of sociological aging theory. Gerontologist 40(5):517–530

Mollenkopf J, Champeny A (2009) The neighbourhood context for second-generation education and labour market outcomes in New York. J Ethn Migr Stud 35(7):1181–1199

Moore S (2009) ”No matter what I did I would still end up in the same position”: age as a factor defining older women’s experience of labour market participation. Work Employ Soc 23(4):655–671

Myck M (2010) Wages and ageing: is there evidence for the ‘Inverse-U’ profile? Oxford B Econ Stat 72(3):282–306

Myck M (2015) Living longer, working longer: the need for a comprehensive approach to labour market reform in response to demographic changes. Eur J Aging 12(1):3–5. doi:10.1007/s10433-014-0332-x

Nash JC (2008) Re-thinking intersectionality. Fem Rev 89(89):1–15

O’Rand AM (1996) The precious and the precocious: understanding cumulative disadvantage and cumulative advantage over the life course. Gerontologist 36(2):230–238

Riphahn R (2003) Cohort effects in the educational attainment of second generation immigrants in Germany: an analysis of census data. In: Zimmermann KF, Constant A (eds) How labor migrants fare. Springer, Berlin, pp 251–277

Salentin K (2014) Sampling the ethnic minority population in Germany: the background to “Migration Background” methods, data, analyses. J Quant Method Surv Methodol 8(1):25–52

Simonson J, Gordo LR, Kelle N (2014) Parenthood and subsequent employment: changes in the labor participation of fathers across cohorts as compared to mothers. Fathering 12(3):320–336. doi:10.3149/fth.1203.320

Statistisches Bundesamt (2011) Bevölkerung und Erwerbstätigkeit: Bevölkerung mit Migrationshintergrund. Ergebnisse des Mikrozensus 2011 (Population and employment: population with migration background. Results of the Microcensus 2011). Statistisches Bundesamt, Wiesbaden

Statistisches Bundesamt (2015) Bevölkerung und Erwerbstätigkeit. Bevölkerung mit Migrationshintergrund. Fachserie 1, Reihe 2.2 (Population and employment: population with migration background, Serie 1, line 2.2.) Statistisches Bundesamt, Wiesbaden

Tijdens KG, Van Klaveren M (2012) Frozen in time: gender pay gap unchanged for 10 years. ITUC, Brussels

Vincent J (1995) Inequality and old age. UCL Press, London

Wagner GG, Frick JR, Schupp J (2007) The German Socio-Economic Panel Study (SOEP)—scope, evolution and enhancements. Schmollers Jahrb 127(1):139–169

Walsemann KM, Geronimus T, Gee GC (2008) Accumulating disadvantage over the life course: evidence from a longitudinal study investigating the relationship between educational advantage in youth and health in middle age. Res Aging 30(2):169–199

Warnes A, Williams A (2006) Older migrants in Europe: a new focus for migration studies. J Ethn Migr Stud 32(8):1–34

Wirth L (1945) The problem of minority groups. In: Lindton (ed) The science of man in the world crisis. Columbia University Press, New York, pp 374–399

Woodward K (2006) Performing age, performing gender. NWSA J 18(1):162–189

Xu W, Leffler A (1992) Gender and race effects on occupational prestige, segregation, and earnings. Gender Soc 6(3):376–392

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Responsible editor: H. Litwin.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Stypińska, J., Gordo, L.R. Gender, age and migration: an intersectional approach to inequalities in the labour market. Eur J Ageing 15, 23–33 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-017-0419-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-017-0419-2