Abstract

Interactions between Helicobacter Pylori (HP) and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) are a complex issue. Several pathophysiological factors influence the development and the course of GERD, HP infection might be only one of these. Many studies emphasize the co-existence of these diseases. HP infection could contribute to GERD through both a protective and an aggressive role. Gastric acid secretion is a key factor in the pathophysiology of reflux esophagitis. Depending on the type of gastritis related to HP, acid secretion may either increase or decrease. Gastritis in corpus leads to hypoacidity, while antrum gastritis leads to hyperacidity. In cases of antral gastritis and duodenal ulcers which have hyperacidity, the expectation is an improvement in pre-existing reflux esophagitis after eradication of HP. In adults, HP infection is often associated with atrophic gastritis in the corpus. Atrophic gastritis may protect against GERD. Pangastritis which leads to gastric atrophy is commonly associated with CagA strains of HP and it causes more severe gastric inflammation. In case of HP-positive corpus gastritis in the stomach, pangastritis, and atrophic gastritis, reflux esophagitis occurs frequently after eradication of HP. Nonetheless, as a predisposing disease of gastric cancer, HP should be treated. In conclusion, as the determinative factors affecting GERD involving in HP, detailed data on the location of gastric inflammation and CagA positivity should be obtained by the studies at future.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Helicobacter pylori (HP) infection and Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD) are common diseases worldwide. HP infection is most likely acquired in childhood [1]. While the prevalence of HP infection is decreasing all over the world due to better living conditions, better hygiene and frequent use of antibiotics in childhood, GERD is increasing. The protective role of HP infection for GERD was first reported by Labenz in 1997 [2]. Thereafter, some authors have pointed out the interaction which involves gastric acid secretion between these diseases. HP infection could contribute to GERD through different mechanisms. It may have both a protective [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12] and an aggressive role in GERD incidence and severity. Many studies emphasize the co-existence of these diseases [13,14,15].This review aimed to understand and clarify the interactions between HP and GERD in both children and adults.

Pathogenesis

In the pathogenesis of GERD, the esophagus, LES and stomach work as a single functional unit controlled by neuro-hormonal factors. Parasympathetic dysfunction adversely affects the motor activity of this area by increasing the transient LES relaxation number and impairing LES pressure, esophageal acid clearance and motility of the proximal stomach. Recently, numerous investigations have been performed to elucidate the role of HP infection in GERD pathogenesis with the most concern given to its potency to increase gastric acid secretion.

The effect of HP on GERD

HP infection implicates in the development of gastritis, and duodenal and gastric ulcers. Depending on the type of gastritis, acid secretion may either increase or decrease. Genetic factors change the immune and inflammatory response to HP infection. The distribution of gastritis (antrum, corpus or pangastritis) is also important in the development of reflux esophagitis. Gastritis in the corpus leads to hypoacidity, while antrum gastritis causes hyperacidity. The positive effects of HP eradication are most likely due to antral predominant gastritis which is the most common type in childhood. However, corpus-predominant gastritis is more common in adults [15,16,17,18].

Antrum-predominant gastritis is characterized by hypergastrinemia and more acidity. The risk of either peptic ulceration or GERD increases in patients with antral gastritis [19]. After eradication of HP, acid secretion will return at least to normal in antrum-predominant gastritis. The expectation is that, in these patients, HP eradication should improve or not affect reflux esophagitis [19,20,21,22,23].

The region secreting gastric acid is the corpus of the stomach which is full of parietal cells. As a result of prolonged inflammation of the corpus, in cases with atrophic gastritis or severe corpus gastritis, there is an association with decreased gastric acid production. This process is considered to be the main mechanism by which HP infection inhibits the onset of GERD [1]. HP eradication may result in increased acid secretion and cause reflux esophagitis or aggravation of GERD symptoms [5, 7, 19, 20, 23].

In the adult patient with pangastritis, there is an irreversible reduction in gastric acid secretion in contrast to those with duodenal ulcer. In case of pangastritis, gastric acid production decreases [5] and HP infection prevents reflux esophagitis by decreasing gastric acid secretion. In cases with HP-positive gastritis and gastric ulcers, reflux esophagitis occurs frequently after eradication [5, 23]. PPIs are effective for curing reflux esophagitis after eradication. On the other hand, in cases of duodenal ulcers which have hyperacidity, there was an improvement in pre-existing reflux esophagitis after eradication of HP [20, 24]. Some adult studies supported the claim that HP eradication results in decreased symptoms of GERD [10, 23, 25]; however, others reported no impact on GER symptoms [26, 27] (Tables 1, 2) [28,29,30,31]. Unfortunately, lots of the studies do not emphasize the location of gastric inflammation while evaluating the effect on GERD of HP infection.

Also, the importance of an anti-reflux barrier should be kept in mind. In terms of developing reflux esophagitis, patients with impairment of the barrier, such as a hiatal hernia, will be affected more by HP eradication [23, 32]. Koike [5] reported that reflux esophagitis developed after HP eradication in patients with a hiatal hernia.

The effects of geographic differentiation

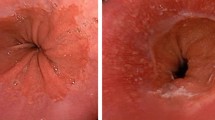

The reported prevalence of GERD in patients of all ages worldwide is increasing. Host racial differences affecting HP-related gastritis may have an influence on symptoms and severity of GERD between Asian and Western countries. Epidemiological studies show that the prevalence of GERD ranges from 20 to 40% in Western countries and from 5 to 17% in Asian countries [33, 34]; however, the prevalence is increasing in Asian populations [35]. According to previous Asian population-based studies, the prevalence of GERD is reported to have a lower prevalence in patients with HP infection [23, 36,37,38,39,40,41]. In the populations in which there is significant involvement of corpus gastritis, the eradication of HP leads to an increase in esophageal acid exposure and a worsening of the symptoms. Population-based studies have shown that reflux disorders are less common in Eastern Asia than in Europe and North America [42, 43]. The reason is that in East-Asian patients, HP-related gastritis is primarily located in the corpus [17, 44]. However, in the Far East, European and North America populations, patients with HP infection experience the complications due to antrum-predominant gastritis [45]. HP infection does not lead to a major change in gastric acid secretion because of the antral involvement. However, gastric acid secretion associated with HP infection decreases in the majority of cases in Asian countries [23, 46]. In adult studies, increased severity of GERD after eradication of HP has been reported especially among Asians compared to North Americans and Europeans [1, 5, 47,48,49,50] (Fig. 1a, b). Twenty-eight studies of the prevalence of GERD reported a prevalence of 18.1–27.8% in North America, 8.8–25.9% in Europe, 2.5–7.8% in East Asia, 8.7–33.1% in the Middle East, 11.6% in Australia, and 23.0% in South America [51, 52]. African-Americans and Asians also appear to be at lower risk for the development of GERD-related complications, including Barrett’s esophagus (BE) [51].

The effects on children

During childhood, HP is associated with antral predominant gastritis and duodenal ulcers [44, 53, 54]. Determining the prevalence of HP is also difficult because of frequent use of antibiotics in childhood. Some authors pointed out that antibiotics such as Amoxicillin and Clarithromycin could eradicate HP in 10–50% of patients [18, 55, 56]. Almost all of the children with chronic active gastritis colonized with HP can be diagnosed using endoscopy/biopsy [57,58,59,60]. However, endoscopy is not a widespread application for diagnosis of GERD in childhood.

Children and adolescents who have HP infection are more likely to have antral gastritis predominantly [57,58,59,60,61] with prevalence ranging from 1.9 to 71.0 (median 4.6 years) [62]. In a previous study [63], children from the lower risk populations (USA) were compared with children from a higher risk population (Colombia) which exhibited more severe inflammation and HP colonization density. In both populations, the inflammatory lesions were seen predominantly in the antrum. Carvalho [60] also pointed out that HP density in the antrum was higher than in the corpus in children. In the studies by Langner [58] from Brazil, among children and adolescents, HP-related gastritis was present in the antrum for 27.3% and in the corpus for 4.5% (mean 10.5 years). The study by Carvalho [60] found pangastritis in 61.9% of cases, followed by antrum- (32.1%) and corpus-predominant gastritis (5.9%) (mean 9.5 years). Another study showed that 83% of Chilean children had antrum-predominant gastritis [59]. Hoepler’s [57] study showed that in Austrian children, pangastritis was present in 46% of children who had HP infection, with 50% antrum predominant (mean 10.5 years). In Moon’s [15] study including patients with HP infection, children between 1–10 years and older than 10 years had odds ratios of 7.00 and 5.99, respectively, of having reflux esophagitis compared to patients less than 1 year (mean 8.2 years).

Some studies showed that eradication therapy did not influence the presence of GER [18, 20, 64]. Xinias [17] showed that HP-positive patients with antral gastritis had no clinical improvement after eradication in spite of increasing the mean lower esophageal sphincter pressure and decreasing the “Reflux Index”. Pollet [65] reported that HP eradication did not provoke or worsen GERD in neurologically-impaired children. According to these results, HP may aggravate GERD symptoms in children and eradication of HP does not play a major role in GERD symptoms even among neurologically-handicapped children.

Gastric and duodenal ulcers in children

The prevalence of HP-positive ulcers in children differed between countries. In a European multicenter study, in children, one quarter of cases with ulcers (10.6%) had HP infection [66]. In another study from “the pediatric European register for treatment of HP” (PERTH), the ulcer was determined in 12.3% of children with HP-associated gastritis (2001–2002) [67].

In children, the prevalence of HP with duodenal ulcer (83%) was higher than those with gastric ulcer [61, 62]. The prevalence of peptic ulcer was 6.7% in European children, 35% in Russian children [67], and 6.9% in Chinese children where HP positivity was 56.8% in duodenal ulcer and 33.3% in gastric ulcer [68]. Daugule [69] from Latvia determined that 82% of symptomatic children aged 8–18 years had antral gastritis and 7% had a duodenal ulcer. Finally, HP infection is associated with antral gastritis and duodenal ulcer in childhood. Pollet [65] did not determine ulcers or atrophic gastritis in neurologically-impaired children with HP infection (mean 13 years). In the study by Arent [70], duodenal and gastric ulcers among children aged 10–16 years were mostly linked to HP infection, but not ≤ 9 years.

Atrophic gastritis

Long-term HP infection causes inflammatory sequelae such as atrophic gastritis and intestinal metaplasia in the stomach. Moreover, apart from the distinction between infection of the fundus and of the antrum with consequent hypoacidity and hyperacidity, it should be remembered that the final consequence of HP infection is atrophic gastritis, even in the antrum, with a reduced acid production. In adults, HP infection often is associated with atrophic gastritis which leads to hypochlorhydria and hypergastrinemia [71, 72]. That is, hypochlorhydria and atrophic gastritis may protect against GERD [4,5,6, 9, 73]. Furthermore, atrophic gastritis predisposes individuals to gastric cancer.

Little is known about the prevalence of atrophic gastritis in childhood. Studies in children showed that atrophy and metaplasia were highly rare in childhood [20, 57,58,59,60, 71, 74,75,76,77,78]. In studies which focused on HP-positive children, the prevalence was reported as from 0 to 4% [74]. In the study by Hoepler [57] from Austria, one case was determined to have severe pangastritis and atrophy; a girl of 15 years old. In a study from Tunisia, the prevalence of pangastritis was 9.3 or 34.6% for moderate or severe atrophy (Grade 2–3) [79]. HP-induced gastric inflammation can cause atrophy in Japanese children, predominantly in the antrum [71]. The prevalence of grade 2 or 3 atrophy in the antrum was 10.7% and in the corpus 4.3% (mean 12.1 years). Furthermore, none of the children from two studies presented intestinal metaplasia. The prevalence of gastric atrophy and intestinal metaplasia varies according to the geographic/genetic origins as well as environmental factors [80]. Unfortunately, there is no pediatric study which compared the prevalence of gastric atrophy according to geographic, genetic or environmental factors.

The effects on severity of HP infection

HP infection was present in 27% of children in 19 centers from 14 European countries. The frequency of ulcers and/or erosions in children was 8.1%, occurring mainly in the second decade of life [66]. Probably, high-level histological scores may be a problem mainly among patients older than 20 years old. Keep in mind that the patients who had impairment of the barrier, such as a hiatal hernia, are a high-risk group in terms of developing severe histological scores as a complication of reflux esophagitis.

Little is known about the exact histological features of reflux and its contributions to esophageal and gastric mucosal lesions in children with HP-related gastritis. The studies which examined and scored the histological characteristics of the mucosa showed that in the presence HP, esophagitis was less severe according to the Los Angeles classification system (grade A) [12, 18]. Higher histological scores were determined in antrum-predominant gastritis in children, as expected [57,58,59,60].

Malignancy

Gastric cancer is most common cancer in Korean and Japanese men. Despite the high prevalence of HP infection in Bangladesh, Thailand, and India; however, the incidence of gastric cancer is extremely low in these countries in contrast to Japan. Antrum-predominant gastritis is more common in Bangladesh among all age groups with HP infection. In the Japanese, antrum-predominant gastritis is common in those younger than 59 years and corpus-predominant gastritis in cases older than 60 years [81]. Atrophy and metaplasia are the complications of pangastritis or corpus-predominant gastritis.

In a community-based study by Corley et al. [82], the prevalences of HP infection were 11.7%, 9.6%, and 22.7% in the BE cases, GERD patients, and controls, respectively. Persons with BE have a substantially increased risk of EAC. The decreasing prevalence of H. pylori infection in many countries correlates with the recent marked increases in EAC incidence, and the prevalence of HP infection is lower in demographic groups at higher risk of EAC. In the case of H. pylori infection protecting against GERD in corpus-predominant gastritis, the development of BE and EAC will decrease. In contrast, eradication of HP infection will increase the risk of BE and EAC. The prevalence of HP infection in EAC patients and distal gastric cancer has been compared by Inomata in Japan [83]. EAC was observed in 9.4% of the 852 cases. The rate of HP infection was lower in patients with EAC than gastric cancer (73.8 vs. 94.1%). The prevalence of corporal gastritis was lower in patients with EAC than gastric cancer also (80.7 vs. 94.6%). Concurrent HP infection and corporal gastritis were not observed in patients with BE.

Pediatric cohort studies pointed out that acute inflammation may be less intense in children, but that chronic inflammation may increase in intensity. In the study by Carvalho [60], the histological scores for esophagitis in Brazilian children and adolescents were higher in the non-infected group than in the HP-infected group and, among HP-positive children, neither intestinal metaplasia nor gastric atrophy was determined. In a study from a high-risk population (58 Korean and 115 Colombian; mean 15 years), the atrophic mucosa was present in 16% of children (31% intestinal metaplasia; 63% pseudopyloric metaplasia; 6% both) [84]. In case of atrophic gastritis or gastric cancer, HP infection prevents reflux esophagitis by decreasing gastric acid secretion. Atrophic gastritis is a risk factor for progression of malignancy even in children. Furthermore, children are less prone to develop HP-related malignancy which is only sporadically reported because of the time required for this development; it may take longer from childhood to adulthood [85].

Cytotoxin-associated gene A (CagA)

Host genetic factors and CagA strains of HP interact to determine HP and GERD. Therefore, the degree and extent of gastritis are affected by these factors [23]. A high prevalence of Cag A-positive strains has been reported in Asian populations and in some developing countries [86] and ranged between 90 and 97% in Korea, Japan, Malaysia, Southeast Asia, and China. It ranged between 80 and 89% in German, Estonia, and Brazil, ranged between 70 and 79% in Iraq, Iranian, and Turkey [87–89], between 60 and 69% in the United States, and between 40 and 49% in the Netherlands, and Sri Lanka. The prevalence ratios were reported differently from South- and East-Asian countries. Middle East countries had a similar range to that reported from European and North American countries between 60 and 70%.

Pangastritis which leads to gastric atrophy is associated with CagA strains [86, 90]. HP infection with CagA strains is associated with less severe reflux esophagitis due to pangastritis leading to hypochlorhydria. In adult studies, the protective effect of cagA-positive strains of HP against GERD has also been shown in Hong Kong, Iran, and Malaysia [45, 91]. A meta-analysis showed that eradication of Cag A-positive HP was also related to a higher risk of developing GERD [41]. Eradication of Cag A-positive HP leads to recovery of acid secretion capacity and corpus gastritis which might be the cause of the higher incidence of GERD in Asian populations [46]. Thus, it was claimed that HP CagA-positive strains may protect against the development of GERD. The genetic variability of HP strains is dependent on the geographical and ethnic status of human hosts.

Information about the HP strains in children is limited. Geographical location of the studies due to differences in the prevalence of H. Pylori globally is the reason for this heterogeneity [92]. Among children and adolescents with HP infection, the rate of cagA-positive strains was 41.5% in Italy, 58% in Latvia and 46% in Estonia [69, 93]. Sökücü [94] determined that esophageal lesions were less common in Turkish children infected with CagA-positive strains. In the study by Gold [44], gastric inflammation was more severe among children infected with CagA-positive strains. Eradication of HP has resulted in resolution of both esophageal and gastric diseases at 6-month follow-up. Analysis of pediatric HP strains continues to suggest that CagA-positive strains are less prevalent than in adult isolates, but gastric inflammation is more severe [95].

Inflammatory cytokines

CagA protein can induce IL-8 and IL-1β production. Thus, patients infected with CagA-positive strains develop more pronounced inflammation. The outer membrane in inflammatory proteins of HP can also stimulate IL-8 secretion. HP-related corpus-predominant gastritis may have reduced gastric acid probably mediated by cytokines such as interleukin 1. Furthermore, vacuolating cytotoxin A (VacA), especially the virulent form s1m1, inhibits gastric acid secretion by disrupting the gastric parietal cells. This may reduce acid exposure in the esophagus causing less GER symptoms [7, 14, 86].

Children infected with HP have increased gastric concentrations of IL-1β and/or TNF-α, both potent inhibitors of gastric acid secretion [86]. Kutukculer [96] determined that TNF-alpha levels in gastric juice and in gastric biopsy were found to be significantly higher in patients with HP-positive gastritis than those in children without it. Increased levels of inflammatory cytokines may contribute to the pathogenesis of HP-associated gastritis in childhood.

Discussion

The prevalence of GERD has increased during the past 2 decades in the general population. While decreasing the rate of HP infection, GERD has been increasing. If this trend continues, in the future, HP infection rate will be extremely low in some countries in Asia. However, the incidence of GERD-associated severe complications, such as BE or EAC will also increase as a common health problem. Approximately 20–40% of patients with GERD have erosive esophagitis, and 65–70% of them have more severe complications at follow-up, such as stricture, BE, or EAC. For this reason, GERD with or without HP infection should be treated. Identifying the mechanism of abnormalities helps effective causative therapy. The role of HP infection in GERD have been related to gastric acid output, on the other hand, the evidence from pathophysiological studies show that TLESRs are the predominant mechanism of reflux in both children and adults with GERD without HP infection. The presence of HP, especially cagA-positive strains, tends to be protective against erosive esophagitis and BE by gastric atrophy and decreasing acid production which leads to decreased esophageal exposure to acid. Gastric acid secretion in patients with BE and BE-related EAC do not differ from those of appropriately matched controls with esophagitis alone.

The results of HP eradication depend on the type and location of gastritis in the patients with GERD. In the populations in which there is significant involvement of corpus gastritis, the eradication of HP leads to an increase in esophageal acid exposure and a worsening of the symptoms. Atrophic gastritis seems to be protective against GERD. In these patients, after the eradication of HP, GERD symptoms aggravate and reflux esophagitis occurs frequently. Studies in different geographic regions or populations may result in entirely different outcomes. The geographical location and genetic predisposition may involve factors that influence the pattern of gastritis. Studies should be evaluated based on geographic and ethnic characteristics. In a meta-analysis, subgroup analyses were carried out separately on studies from Asian (N. 3236; 4 RCTs) and western countries (N. 2922; 8 RCTs) and showed a significantly higher risk for the development of GERD in patients with eradication therapy compared with controls in Asian studies (RR 4.53); however, this risk was not observed in the subgroup analysis of western studies (RR 1.22). The protective effect may exist only in Asian populations [41].

The Maastricht IV/Florence consensus report describes that eradication of HP in populations of infected patients, on average, neither causes nor exacerbates GERD. Therefore, the presence of GERD should not dissuade practitioners from HP eradication treatment where indicated. In most populations, the changes in acid production after HP treatment have no proven clinical relevance and should not be used as an argument to treat or not to treat HP [97]. According to the guidelines for the management of HP infection in Japan in 2009, when long-term observation of patients with reflux esophagitis is performed following HP eradication, most of them remain in grade A or B of the Los Angeles Classification and their symptoms may not become more severe. The Maastricht IV/Florence consensus report describes that long-term treatment with PPIs in HP-positive patients is associated with the development of corpus-predominant gastritis. This accelerates the process of loss of specialized glands, leading to atrophic gastritis. Eradication of HP in patients receiving long-term PPIs heals gastritis and prevents the progression to atrophic gastritis. Therefore, in HP-infected patients with reflux esophagitis, eradication therapy is recommended prior to the long-term use of PPIs [98].

In conclusion, the determinative factors affecting GERD involving in HP are the location of gastric inflammation and CagA positivity in both children and adults. The reason why HP affects the corpus or antrum of the stomach in different populations may be due to genetic differentiation and CagA-positive strains of HP which is associated with pangastritis leading to hypochlorhydria and less severe GERD. We hope that this article puts into perspective to understand this complex relationship. Data on the location of gastric inflammation and CagA positivity should be obtained by further studies.

Limitation

First, only children who underwent upper gastrointestinal endoscopy were enrolled in the studies. Second, lots of the studies do not emphasize the location of gastric inflammation while evaluating the effect on GERD of HP infection.

References

Ghoshal UC, Chourasia D. Gastroesophageal reflux disease and Helicobacter pylori: what may be the relationship? J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2010;16:243–50.

Labenz J, Blum AL. Curing Hp infection in patients with duodenal ulcer may provoke reflux oesophagitis. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:1442–7.

Schwizer W, Fox M. Helicobacter pylori and gastroesophageal reflux disease: a complex organism in a complex host. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2004;38:12–5.

Manes G, Esposito P, Lioniello M, et al. Manometric and pH metric features in gastroesophageal reflux disease patients with and without Helicobacter pylori infection. Dig Liver Dis. 2000;32:372–7.

Koike T, Ohara S, Sekine H, Iijima K, Abe Y, Kato K, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection prevents erosive reflux oesophagitis by decreasing gastric acid secretion. Gut. 2001;49:330–4.

El Serag HB, Sonnenberg A, Jamal MM, et al. Corpus gastritis is protective against reflux esophagitis. Gut. 1999;45:181–5.

Grande M, Cadeddu F, Villa M, Attina GM, Muzi MG, Nigro C, et al. Helicobacter pylori and gastroesophageal reflux disease. World J Surg Oncol. 2008;6:74.

Koike T, Ohara S, Sekine H, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection inhibits reflux esophagitis by inducing atrophic gastritis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:3268–72.

Fallone CA, Barkun AN, Friedman G, et al. Is Helicobacter pylori eradication associated with gastroesophageal reflux disease? Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:914–20.

Wu JCY, Chan FKL, Wong SK, et al. Effect of H pylori eradication on esophageal acid exposure in patients with reflux esophagitis. Aliment Pharmacol Therap. 2002;16:545–52.

Sugimoto M, Uotani T, Ichikawa H, Andoh A, Furuta T. Gastroesophageal reflux disease in time covering eradication for all patients infected with Helicobacter pylori in Japan. Digestion. 2016;93:24–31.

Lupu VV, Ignat A, Ciubotariu G, Ciubară A, Moscalu M, Burlea M. Helicobacter pylori infection and gastroesophageal reflux in children. Dis Esophagus. 2016;29:1007–12.

Zentiline P, Iritano E, Vignale C, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection is not involved in the pathogenesis of either erosive or non-erosive gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17:1057–64.

Sharma P, Vakil N. Helicobacter pylori and reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17:287–305.

Moon A, Solomon A, Beneck D, Cunningham-Rundles S. Positive association between Helicobacter pylori and gastroesophageal reflux disease in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2009;49:283–8.

Hackelsberger A, Gunther T, Schultze V, et al. Role of aging in the expression of Helicobacter pylori gastritis in the antrum, corpus, and cardia. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1999;34:138–43.

Xinias I, Maris T, Mavroudi A, Panteliadis C, Vandenplas Y. Helicobacter pylori infection has no impact on manometric and pH-metric findings in adolescents and young adults with gastroesophageal reflux and antral gastritis: eradication results to no significant clinical improvement. Pediatr Rep. 2013;5:e3.

Daugule I, Rowland M. Helicobacter pylori infection in children. Helicobacter. 2008;13(Suppl 1):41–6.

Graham DY, Yamaoka YH. H. Pylori and cagA: relationships with gastric cancer, duodenal ulcer, and reflux esophagitis and its complications. Helicobacter. 1998;3:145–51.

Levine A, Milo T, Broide E, et al. Influence of Helicobacter pylori eradication on gastroesophageal reflux symptoms and epigastric pain in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2004;113:54–8.

Lipshutz W, Hughes W, Cohen S. The genesis of lower esophageal sphincter pressure: its identification through the use of gastrin antiserum. J Clin Invest. 1972;51:522–9.

Goyal RK, McGuigan JE. Is gastrin a major determinant of basal lower esophageal sphincter pressure? A double-blind controlled study using high titer gastrin antiserum. J Clin Invest. 1976;57:291–300.

Iijima K, Koike T, Shimosegawa T. Reflux esophagitis triggered after Helicobacter pylori eradication: a noteworthy demerit of eradication therapy among the Japanese? Front Microbiol. 2015;6:566.

Ishiki K, Mizuno M, Take S, et al. Helicobacter pylori eradication improves pre-existing reflux esophagitis in patients with duodenal ulcer disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:474–9.

Laine Loren, Sugg Jennifer. Effect of HP eradication on development of GERD symptoms: a post hoc analysis of eight double blind prospective studies. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:2992–7.

Muramatsu A, Azuma T, Okajima T, et al. Evaluation of treatment for gastrooesophageal reflux disease with a proton pump inhibitor, and relationship between gastro-oesophageal reflux disease and Helicobacter pylori infection in Japan. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20(Suppl 1):102–6.

Vaira D, Vakil N, Rugge M, et al. Effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on development of dyspeptic and reflux disease in healthy asymptomatic subjects. Gut. 2003;52:1543–7.

Minatsuki C, Yamamichi N, Shimamoto T, Kakimoto H, Takahashi Y, Fujishiro M, et al. Background factors of reflux esophagitis and non-erosive reflux disease: a cross-sectional study of 10,837 subjects in Japan. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(7):e69891.

Lee YC, Chen TH, Chiu HM, Shun CT, Chiang H, Liu TY, Wu MS, Lin JT. The benefit of mass eradication of Helicobacter pylori infection: a community-based study of gastric cancer prevention. Gut. 2013;62:676–82.

Tan J, Wang Y, Sun X, Cui W, Ge J, Lin L. The effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy on the development of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Med Sci. 2015;349:364–71.

Wang XT, Zhang M, Chen CY, Lyu B. Helicobacter pylori eradication and gastroesophageal reflux disease: a Meta-analysis. Zhonghua Nei Ke Za Zhi. 2016;55:710–6 (Abstract).

Hamada H, Haruma K, Mihara M, Kamada T, Yoshihara M, Sumii K, et al. High incidence of reflux oesophagitis after eradication therapy for Helicobacter pylori: impacts of hiatal hernia and corpus gastritis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2000;14:729–35.

Moayyedi P, Talley NJ. Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Lancet. 2006;367:2086–100.

Wong BC, Kinoshita Y. Systematic review on epidemiology of gastroesophageal reflux disease in Asia. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:398–407.

Stadtlander CT, Waterbor JW. Molecular epidemiology, pathogenesis and prevention of gastric cancer. Carcinogenesis. 1999;20:2195–208.

Raghunath AS, Hungin AP, Wooff D, Childs S. Systematic review: the effect of Helicobacter pylori and its eradication on gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in patients with duodenal ulcers or reflux oesophagitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20:733–44.

Rokkas T, Pistiolas D, Sechopoulos P, Robotis I, Margantinis G. Relationship between Helicobacter pylori infection and esophageal neoplasia: a meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:1413–7.

Wang C, Yuan Y, Hunt RH. Helicobacter pylori infection and Barrett’s esophagus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:492–500.

Fischbach LA, Nordenstedt H, Kramer JR, Gandhi S, Dick-Onuoha S, Lewis A, et al. The association between Barrett’s esophagus and Helicobacter pylori infection: a meta-analysis. Helicobacter. 2012;17:163–75.

McColl KE. Review article: Helicobacter pylori and gastro-oesophageal reflux disease—the European perspective. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20(Suppl. 8):36–9.

Xie T, Cui X, Zheng H, Chen D, He L, Jiang B. Metaanalysis: eradication of Helicobacter pylori infection is associated with the development of endoscopic gastroesophageal reflux disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;25:1195–205.

Jung HK. Epidemiology of gastroesophageal reflux disease in Asia: a systematic review. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2011;17:14–27.

Dent J, El-Serag HB, Wallander MA, Johansson S. Epidemiology of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: a systematic review. Gut. 2005;54:710–7.

Gold BD. Helicobacter pylori infection in children. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2001;31:247–66.

Shavalipour A, Malekpour H, Dabiri H, Kazemian H, Zojaji H, Bahroudi M. Prevalence of cytotoxin-associated genes of Helicobacter pylori among Iranian GERD patients. Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench. 2017;10:178–83.

Hong SJ, Kim SW. Helicobacter pylori infection in gastroesophageal reflux disease in the Asian countries. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2015;2015:985249.

Park JJ, Kim JW, Kim HJ, et al. The prevalence of and risk factors for Barrett’s esophagus in a Korean population: a nationwide multicenter prospective study. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;43:907–14.

Peng S, Cui Y, Xiao YL, et al. Prevalence of erosive esophagitis and Barrett’s esophagus in the adult Chinese population. Endoscopy. 2009;41:1011–7.

Fujiwara Y, Arakawa T. Epidemiology and clinical characteristics of GERD in the Japanese population. J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:518–34.

Miyamoto M, Haruma K, Kuwabara M, Nagano M, Okamoto T, Tanaka M. High incidence of newly-developed gastroesophageal reflux disease in the Japanese community: a 6-year follow-up study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:393–7.

Sharma P, Wani S, Romero Y, Johnson D, Hamilton F. Racial and geographic issues in gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:2669–80.

Boeckxstaens G, El-Serag HB, Smout AJPM, Kahrilas PJ. Republished: symptomatic reflux disease: the present, the past and the future. Postgrad Med J. 2015;91:46–54.

Sherman P, Czinn S, Drumm B, Gottrand F, Kawakami E, Madrazo A, Oderda G, Seo JK, Sullivan P, Toyoda S, Weaver L, Wu TC. Helicobacter pylori infection in children and adolescents: working group report of the first world congress of pediatric gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2002;35(Suppl 2):S128–33.

Blecker U. Helicobacter pylori-associated gastroduodenal disease in childhood. South Med J. 1997;90:570–6.

Israel DM, Hassall E. Treatment and long-term follow-up of Helicobacter pylori-associated duodenal ulcer disease in children. J Pediatr. 1993;123:53–8.

Peterson WL, Graham DY, Marshall B, et al. Clarithromycin as monotherapy for eradication of Helicobacter pylori: a randomized, double-blind trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88:1860–4.

Hoepler W, Hammer K, Hammer J. Gastric phenotype in children with Helicobacter pylori infection undergoing upper endoscopy. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:293–8.

Langner C, Schneider NI, Plieschnegger W, Schmack B, Bordel H, Höfler B, Eherer AJ, Wolf EM, Rehak P, Vieth M. Cardiac mucosa at the gastro-oesophageal junction: indicator of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease? Data from a prospective central European multicentre study on histological and endoscopic diagnosis of oesophagitis (histoGERD trial). Histopathology. 2014;65:81–9.

Guiraldes E, Peña A, Duarte I, Triviño X, Schultz M, Larraín F, Espinosa MN, Harris P. Nature and extent of gastric lesions in symptomatic Chilean children with Helicobacter pylori associated gastritis. Acta Paediatr. 2002;91:39–44.

Carvalho MA, Machado NC, Ortolan EV, Rodrigues MA. Upper gastrointestinal histopathological findings in children and adolescents with nonulcer dyspepsia with Helicobacter pylori infection. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2012;55:523–9.

Kato S, Nishino Y, Ozawa K, Konno M, Maisawa S, Toyoda S, Tajiri H, Ida S, Fujisawa T, Iinuma K. The prevalence of Helicobacter pylori in Japanese children with gastritis or peptic ulcer disease. J Gastroenterol. 2004;39:734–8.

Macarthur C, Saunders N, Feldman W. Helicobacter pylori, gastroduodenal disease, and recurrent abdominal pain in children. JAMA. 1995;273:729–34.

Bedoya A, Garay J, Sanzón F, Bravo LE, Bravo JC, Correa H, Craver R, Fontham E, Du JX, Correa P. Histopathology of gastritis in Helicobacter pylori-infected children from populations at high and low gastric cancer risk. Hum Pathol. 2003;34:206–13.

Mungan Z, Pınarbaşı Şimşek B. Gastroesophageal reflux disease and the relationship with Helicobacter pylori. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2017;28(Suppl 1):S61–7.

Pollet S, Gottrand F, Vincent P, et al. Gastroesophageal reflux disease and Helicobacter pylori infection in neurologically impaired children: inter-relations and therapeutic implications. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2004;38:70–4.

Kalach N, Bontems P, Koletzko S, Mourad-Baars P, Shcherbakov P, Celinska-Cedro D, Iwanczak B, Gottrand F, Martinez-Gomez MJ, Pehlivanoglu E, Oderda G, Urruzuno P, Casswall T, Lamireau T, Sykora J, Roma-Giannikou E, Veres G, Wewer V, Chong S, Charkaluk ML, Mégraud F, Cadranel S. Frequency and risk factors of gastric and duodenal ulcers or erosions in children: a prospective 1-month European multicenter study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;22:1174–81.

Oderda G, Shcherbakov P, Bontems P, Urruzuno P, Romano C, Gottrand F, Gómez MJ, Ravelli A, Gandullia P, Roma E, Cadranel S, De Giacomo C, Canani RB, Rutigliano V, Pehlivanoglu E, Kalach N, Roggero P, Celinska-Cedro D, Drumm B, Casswall T, Ashorn M, Arvanitakis SN. Results from the pediatric European register for treatment of Helicobacter pylori (PERTH). Helicobacter. 2007;12:150–6.

Tam YH, Lee KH, To KF, Chan KW, Cheung ST. Helicobacter pylori-positive versus Helicobacter pylori-negative idiopathic peptic ulcers in children with their long-term outcomes. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2009;48:299–305.

Daugule I, Rumba I, Engstrand L, Ejderhamn J. Infection with cagA-Positive and cagA-Negative types of Helicobacter pylori among children and adolescents with gastrointestinal symptoms in Latvia. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2003;22:622–4.

Arents NL, Thijs JC, van Zwet AA, Kleibeuker JH. Does the declining prevalence of Helicobacter pylori unmask patients with idiopathic peptic ulcer disease? Trends over an 8 year period. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;16:779–83.

Kato S, Kikuchi S, Nakajima S. When does gastric atrophy develop in Japanese children? Helicobacter. 2008;13:278–81.

Kekki M, Samloff IM, Varis K, Ihamäki T. Serum pepsinogen I and serum gastrin in the screening of severe atrophic corpus gastritis. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1991;186:109–16.

Waldum HL, Sagatun L, Mjønes P. Gastrin and gastric cancer. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2017;8:1.

Dimitrov G, Gottrand F. Does gastric atrophy exist in children? World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:6274–9.

Whitney AE, Guarner J, Hutwagner L, Gold BD. Helicobacter pylori gastritis in children and adults: comparative histopathologic study. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2000;4:279–85.

Usta Y, Saltk-Temizel IN, Ozen H. Gastric atrophy and intestinal metaplasia in Helicobacter pylori infection. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2004;38:548.

Oztürk Y, Büyükgebiz B, Arslan N, Ozer E. Antral glandular atrophy and intestinal metaplasia in children with Helicobacter pylori infection. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2003;37:96–7.

Guarner J, Bartlett J, Whistler T, Pierce-Smith D, Owens M, Kreh R, Czinn S, Gold BD. Can pre-neoplastic lesions be detected in gastric biopsies of children with Helicobacter pylori infection. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2003;37:309–14.

Boukthir S, Mrad SM, Kalach N, Sammoud A. Gastric atrophy and Helicobacter pylori infection in children. Trop Gastroenterol. 2009;30:107–9.

Pacifico L, Anania C, Osborn JF, Ferraro F, Chiesa C. Consequences of Helicobacter pylori infection in children. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:5181–94.

Matsuhisa T, Aftab H. Observation of gastric mucosa in Bangladesh, the country with the lowest incidence of gastric cancer, and Japan, the country with the highest incidence. Helicobacter. 2012;17:396–401.

Corley DA, Kubo A, Levin TR, Block G, Habel L, Zhao W, et al. Helicobacter pylori Infection and the Risk of Barrett’s Oesophagus: a Community-Based Study. Gut. 2008;57:727–33.

Inomata Y, Koike T, Ohara S, Abe Y, Sekine H, Iijima K, et al. Preservation of gastric acid secretion may be important for the development of gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma in Japanese people, irrespective of the H. pylori infection status. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:926–33.

Ricuarte O, Gutierrez O, Cardona H, Kim JG, Graham DY, El-Zimaity HM. Atrophic gastritis in young children and adolescents. J Clin Pathol. 2005;58:1189–93.

Riddell RH. Pathobiology of Helicobacter pylori infection in children. Can J Gastroenterol. 1999;13:599–603.

Ghoshal UC, Tiwari S, Dhingra S, et al. Frequency of Helicobacter pylori and CagA antibody in patients with gastric neoplasms and controls: the Indian enigma. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53:1215–22.

Sayehmiri F, Kiani F, Sayehmiri K, Soroush S, Asadollahi K, Alikhani MY, Delpisheh A, Emaneini M, Bogdanović L, Varzi AM, Zarrilli R, Taherikalani M. Prevalence of cagA and vacA among Helicobacter pylori-infected patients in Iran: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2015;9:686–96.

Nawfal RH, Mohammadi M, Talebkhan Y, Doraghi MP, Letley DK, Muhammad M, Argent HR, Atherton CJ. Differences in virulence markers between Helicobacter pylori strains from Iraq and those from Iran: potential importance of regional differences in H. pylori- associated disease. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46:1774–9.

Saribasak H, Salih BA, Yamaoka Y, Sander E. Analysis of Helicobacter pylori genotypes and correlation with clinical outcome in Turkey. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:1648–51.

Chiba H, Gunji T, Sato H, Iijima K, Fujibayashi K, Okumura M, et al. A cross-sectional study on the risk factors for erosive esophagitis in young adults. Intern Med. 2012;51:1293–9.

Azuma T, Yamazaki S, Yamakawa A, Ohtani M, Muramatsu A, Suto H, et al. Association between diversity in the Src homology 2 domain—containing tyrosine phosphatase binding site of Helicobacter pylori CagA protein and gastric atrophy and cancer. J Infect Dis. 2004;189:820–7.

Luzza F, Pensabene L, Imeneo M, Mancuso M, Giancotti L, La Vecchia AM, Costa MC, Strisciuglio P, Pallone F. Antral nodularity and positive CagA serology are distinct and relevant markers of severe gastric inflammation in children with Helicobacterpylori infection. Helicobacter. 2002;7(1):46–52.

Vorobjova T, Grünberg H, Oona M, Maaroos HI, Nilsson I, Wadström T, Covacci A, Uibo R. Seropositivity to Helicobacter pylori and CagA protein in schoolchildren of different ages living in urban and rural areas in southern Estonia. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;12:97–101.

Sokucu S, Ozden AT, Suoglu OD, Elkabes B, Demir F, Cevikbas U, et al. CagA positivity and its association with gastroduodenal disease in Turkish children undergoing endoscopic investigation. J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:533–9.

Mourad-Baars P, Hussey S, Jones NL. Helicobacter pylori infection and childhood. Helicobacter. 2010;15:53–9.

Kütükçüler N, Aydogdu S, Göksen D, Caglayan S, Yagcyi RV. Increased mucosal inflammatory cytokines in children with Helicobacter pylori-associated gastritis. Acta Paediatr. 1997;86:928–31.

Bytzer P, Megraud F, O’Morain CA, Atherton J, Axon AT, Bazzoli F, et al. European helicobacter study group. Management of Helicobacter pylori infection–the Maastricht IV/Florence consensus report. Gut. 2012;61:646–64.

Asaka M, Kato M, Takahashi S, Fukuda Y, Sugiyama T, Ota H, et al. Japanese Society for Helicobacter Research. Guidelines for the management of Helicobacter pylori infection in Japan: 2009 revised edition. Helicobacter. 2010;15:1–20.

Kawanishi M. Development of reflux esophagitis following Helicobacter pylori eradication. J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:1024–8.

Take S, Mizuno M, Ishiki K, Nagahara Y, Yoshida To, Yokota K, et al. Helicobacter pylori eradication may induce de novo, but transient and mild, reflux esophagitis: prospective endoscopic evaluation. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;24:107–13.

Inoue H, Imoto I, Taguchi Y, Kuroda M, Nakamura M, Horiki N, et al. Reflux esophagitis after eradication of Helicobacter pylori is associated with the degree of hiatal hernia. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2004;39:1061–5.

Nam SY, Choi IJ, Ryu KH, Kim BC, Kim CG, Nam BH. Effect of Helicobacter pylori infection and its eradication on reflux esophagitis and reflux symptoms. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:2153–62.

Kim N, Lim SH, Lee KH. No protective role of Helicobacter pylori in the pathogenesis of reflux esophagitis in patients with duodenal or benign gastric ulcer in Korea. Dig Dis Sci. 2001;46:2724–32.

Kim N, Lee SW, Kim JI, Baik GH, Kim SJ, Seo GS, et al. Effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on the development of reflux esophagitis and gastroesophageal reflux symptoms: a nationwide multi-center prospective study. Gut Liver. 2011;5:437–46.

Wu JC, Chan FK, Ching JY, Leung WK, Hui Y, Leong R, et al. Effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on treatment of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: a double blind, placebo controlled, randomised trial. Gut. 2004;53:174–9.

Vakil N, Talley NJ, Stolte M, Sundin M, Junghard O, Bolling-Sternevald O. Patterns of gastritis and the effect of eradicating Helicobacter pylori on gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in Western patients with non-ulcer dyspepsia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24:55–63.

Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O’Morain CA, Atherton J, Axon ATR, Bazzoli F, et al. Management of Helicobacter pylori infection – the Maastricht IV/Florence Consensus Report. Gut. 2012;61:646–64.

Bytzer P, Aalykke C, Rune S, Weywadt L, Gjorup T, Eriksen J, et al. Eradication of Helicobacter pylori compared with long-term acid suppression in duodenal ulcer disease. A randomized trial with 2-year follow-up. The Danish Ulcer Study Group. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2000;35:1023–32.

Harvey RF, Lane JA, Murray LJ, Harvey IM, Donovan JL, Nair P. Randomised controlled trial of effects of Helicobacter pylori infection and its eradication on heartburn and gastro-oesophageal reflux: Bristol helicobacter project. BMJ. 2004;328:1417.

Ott EA, Mazzoleni LE, Edelweiss MI, Sander GB, Wortmann AC, Theil AL, et al. Helicobacter pylori eradication does not cause reflux oesophagitis in functional dyspeptic patients: a randomized, investigator-blinded, placebo-controlled trial. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21:1231–9.

Befrits R, Sjostedt S, Odman B, Sorngard H, Lindberg G. Curing Helicobacter pylori infection in patients with duodenal ulcer does not provoke gastroesophageal reflux disease. Helicobacter. 2000;5:202–5.

Moayyedi P, Bardhan C, Young L, Dixon MF, Brown L, Axon AT. Helicobacter pylori eradication does not exacerbate reflux symptoms in gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterology. 2001;121:1120–6.

Saad AM, Choudhary A, Bechtold ML. Effect of Helicobacter pylori treatment on gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD): meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2012;47:129–35.

Cremonini F, Di Caro S, Delgado-Aros S, Sepulveda A, Gasbarrini G, Gasbarrini A, Camilleri M. Meta analysis: the relationship between Helicobacter pylori infection and gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;18:279–89.

Yaghoobi M, Farrokhyar F, Yuan Y, Hunt RH. Is there an increased risk of GERD after Helicobacter pylori eradication?: a meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:1007–13.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Statement

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any author.

Conflict of interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yucel, O. Interactions between Helicobacter pylori and gastroesophageal reflux disease. Esophagus 16, 52–62 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10388-018-0637-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10388-018-0637-5