Abstract

Information on the effects of dental treatment must be identified and factors that hinder the continuation of dental treatment must be identified to provide appropriate domiciliary dental care (DDC). This study aimed to clarify the treatment outcomes of DDC for older adults and the factors that impede the continuation of such care. This prospective study was conducted at a Japanese clinic specializing in dental care for older adults. The functional status, nutritional status, oral assessment, details of the dental treatment, and outcomes after 6 months of older adults receiving DDC were surveyed. The Oral Health Assessment Tool (OHAT) was used for oral assessment. Cox proportional hazards analysis was used to analyze the factors at the first visit that were associated with treatment continuation. A total of 72 participants (mean age, 85.8 ± 6.9) were included. Twenty-three participants (31.9%) could not continue treatment after 6 months. The most frequently performed procedures were oral care and dysphagia rehabilitation, followed by prosthetic treatment, then tooth extraction. The percentage of participants with teeth that required extraction after 6 months and the total OHAT score decreased significantly. The Barthel Index, Mini Nutritional Assessment Short-Form, and rinsing ability were significantly associated with treatment continuation. Furthermore, instrumental activities of daily living (ADL) and the OHAT “tongue” sub-item were correlated with treatment continuation. In conclusion, DDC improved the oral health status of older adults after 6 months. Factors that impeded treatment continuation were decreased ADL, decreased nutritional status, difficulty in rinsing, and changes in the tongue such as tongue coating.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Dental care is mainly provided at outpatient clinics, which means that appropriate dental treatment cannot be provided to older adults who receive home medical care. Oral diseases have a significant impact on physical and mental health conditions [1, 2]; hence, appropriate domiciliary dental care (DDC) must be provided for the well-being of older adults who receive home medical care.

Several studies have reported the progress and effects of dental treatment at hospitals and facilities [2,3,4,5,6,7]. Professional oral hygiene care and multidisciplinary oral hygiene program education can reportedly lead to favorable outcomes, such as reduced incidence of pneumonia, improved oral intake, increased home discharge, and reduced in-hospital mortality. However, there is insufficient data regarding the course of dental treatment and its association with outcomes in older adults who receive home medical care. Oral hygiene programs [8,9,10] and dysphagia rehabilitation [11] have also yielded positive outcomes for community-dwelling older adults with dementia and frail older adults. A preliminary study on older adults who require home care focused on occlusal restoration with removable prostheses and reported that maintaining and restoring occlusal support was associated with a better survival prognosis in < 85-year-old participants; however, the effect decreased in ≥ 85-year-old participants [12]. However, the relationship between oral changes that are associated with comprehensive dental treatment and factors that impede dental treatment continuation has yet to be clarified.

There is a growing need to promote preventive and curative oral health and dental care for older adults who live at home. Therefore, information on the effects of dental treatment must be disseminated, and factors that impede treatment continuation must be identified. With this in mind, this study aimed to clarify the treatment outcomes of DDC and factors that impede treatment continuation among older adults receiving DDC.

Materials and methods

This prospective study was conducted in a city with a population of approximately 120,000 people in Tokyo, Japan, from May 2018 to March 2023. We included older adults who were (1) ≥ 65 years old, who received home medical care at a single in-home treatment support clinic and (2) recommended for DDC by their physician and gave their consent. The physicians asked the patients and their families whether they wished to receive DDC within the scope of a regular home visit. If requested, the participant was referred to Tama Oral Rehabilitation Clinic, The Nippon Dental University, a clinic that specializes in dental care and dysphagia rehabilitation for older adults. Thereafter, a dentist with more than 5 years of experience in gerodontology at the same clinic started providing DDC. Older adults who (1) did not want to continue DDC and refused treatment and (2) had terminal cancer were excluded from the study. The results of dental treatment, changes in the oral status, and treatment continuation were evaluated 6 months after the first visit.

DDC in Japan

Only a handful of countries provide DDC. To the best of our knowledge, such services were only available in Taiwan [13, 14]. Japan has a universal health insurance coverage system, and DDC was included in the medical insurance in 1998. Thereafter, this was also covered by long-term care insurance for people who require nursing care while living at home. In other words, services are integrated from both the medical insurance and long-term care insurance business. There are several issues concerning DDC, such as the increased number of dental treatment fee items and the fact that the system has changed according to the current demands.

However, most of these issues can be resolved by the patient or family members who contact the (1) dental clinic directly and (2) the person in charge, such as a government agency or a medical care professional. If patients and their families do not understand the existence or necessity of DDC, medical care professionals may refer them to dental clinics that provide DDC.

Measurements

Functional status

Level of care

In 2000, Japan implemented a long-term care insurance system. Individuals are categorized into one of seven levels of care based on the estimated total hours of caregiving required: comprising two support levels and five care levels. The spectrum ranges from the lowest support level 1 to the highest care level 5 [15]. Services are tailored according to the individual’s assigned level of care.

Activities of daily living (ADL)

The Barthel Index [16] and Lawton’s Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL) [17] were used.

Charlson comorbidity index (CCI)

The Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) [18, 19] was assessed based on the patient information form submitted by the physician.

Living with family

We inquired whether the participant lived together with family members.

Treatment results

After starting DDC, data on death, institutionalization, and hospital admission were collected. After 6 months, those who continued receiving DDC were regarded as participants who were able to continue treatment, and those who did not were regarded as those who were unable to continue treatment.

Nutritional status

The Mini Nutritional Assessment-Short Form [20] was used.

Oral intake function

Oral intake function was evaluated using the Food Intake LEVEL Scale (FILS) [21]. FILS was defined as follows: Level 1–6, tube feeding; Level 7, easy-to-swallow food orally ingested in three meals with no alternative nutrition given; Level 8, the patient eats three meals, only excluding food that is particularly difficult to swallow; Level 9, no dietary restriction, and patient ingesting three meals orally, with medical considerations; and Level 10, normal.

Dental assessment

The total number of teeth, number of functional teeth, number of caries, number of mobile teeth, Japanese version of the Oral Health Assessment Tool (OHAT-J) score [22], details of dental treatment, and other items were surveyed.

Number of functional teeth

Teeth that were useful for mastication were counted regardless of whether they were natural or treated teeth. Prostheses were also included.

Carious teeth

The number and proportion of caries were calculated. The severity of caries was assessed using periapical radiographs. Teeth with severe carious lesions that were deemed untreatable with any restorative treatment were recorded as “Teeth that require extraction” [23].

Mobile teeth

According to Miller's classification [24], the number of teeth with 1–2 mm horizontal mobility (Class 2 mobility) and > 2 mm horizontal and vertical mobility (Class 3 mobility) were counted. Teeth with Class 3 mobility are more likely to fall out. Tooth extraction is favored in cases such as in older adults with reduced functional status that are prone to accidental ingestion and aspiration [25]. Severely carious teeth and teeth with Class 3 mobility were recorded as “Teeth that require extraction”.

OHAT

OHAT-J was used as an assessment tool for oral health status [22]. OHAT [26] is an oral assessment tool developed for older adults and is used by many professions in various fields [27]. The evaluation items comprise eight items: lips, tongue, gums and tissues, saliva, natural teeth, dentures, oral cleanliness, and dental pain. Each item is evaluated on a three-point scale, with each score indicating the following: "healthy" (0 points), "some changes observed" (1 point), and "unhealthy" (2 points). The total score of OHAT ranges from 0 to 16 points. A previous study conducted at an acute care hospital reported that a total score of ≥ 3 was an independent predictor of death [28], whereas a study conducted at a rehabilitation hospital demonstrated that a total score of ≥ 4 indicated that ADL is unlikely to improve [29]. OHAT classified the sub-items into two groups of 0 and ≥ 1 points.

Dental treatment

The details of the dental treatment performed within 6 months were tabulated by multiple choice. Dental treatments were classified into prosthetic treatment (new and adjustment/repair), oral care, extraction, restorative treatment, and dysphagia rehabilitation.

Other measures

The other measures used were (1) the presence or absence of assistance for oral cleaning, (2) rinsing ability, and (3) the last dental visit.

Sample size calculation

The sample size was calculated using G*Power 3.1.9.4 Statistical Power Analyzes (University of Dusseldorf, Germany) with an α error of 0.05, β of 0.8, and medium effect size, requiring a minimum of 88 individuals.

Statistical analysis

The chi-square test, Fisher's exact test, and Kruskal–Wallis test were used to examine each baseline endpoint for treatment continuation. The Wilcoxon's signed and McNemar’s tests were performed for changes in the oral status due to dental treatment. For the details of the dental treatment, crude hazard ratios and hazard ratios adjusted for age (years), care level, and total OHAT score were calculated with a 95% confidence interval using the Cox proportional hazards model with treatment continuation as the objective variable. Similarly, for factors that impede treatment continuation, crude hazard ratios and hazard ratios adjusted for age (years) and level of care were calculated with a 95% confidence interval using the Cox proportional hazards with treatment continuation as the objective variable. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 27 (IBM Corp., Armonk, N.Y., USA) was used for all statistical processing. The significant difference was set at < 5%. For the missing data, each analysis was performed with complete cases.

Results

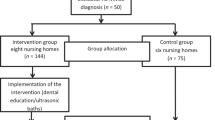

Figure 1 shows the study flow chart. Among the 87 participants, seven people with terminal cancer and eight people who refused treatment were excluded. The final number of participants was 72 (34 men, 38; women, 72; mean age, 85.8 ± 6.9 years; median, 87.0 years [interquartile range (IQR), 82.0–90.75]). Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics classified by whether or not participants continued treatment. The average care level was 2.99 ± 0.98 (median, 2.0; IQR, 2.0–5.0). The average OHAT total score was 5.55 ± 2.50 (median, 5.0; IQR, 4.0–7.5). After 6 months, 49 patients continued treatment, and 23 (31.9%) were unable to continue. Among those who were unable to continue, 15 died, four were admitted to an institution, and four were hospitalized. The mean number of days to the event was 76.9 ± 47.2 days (median, 73 days; IQR, 37.0–117.0).

Figure 2 and Table 2 show the details of the dental treatment. Overall, 70 participants (97.2%) received treatment, and two participants (2.8%) were followed up. Thirty-one participants out of 70 (44.3%; 26 participants for prosthetic repair, and 16 participants for new prostheses) received prosthetic treatment, 39 participants (55.7%) received oral care, and 23 participants (32.9%) underwent extraction. The number of extracted teeth (minimum–maximum) was 1–24, 11 participants (15.7%) underwent restorative treatment, and the number of treated teeth was 1–9 (minimum–maximum). Thirty-seven patients (52.9%) received dysphagia rehabilitation (Multiple choice).

Table 2 shows the results of the Cox proportional hazards analysis on treatment continuation and differences in details of the dental treatment. In a multivariate model adjusted for age, care level, and OHAT total score, tooth extraction was significantly performed in those who were able to continue treatment compared with those who were not. Prosthetic adjustment/repair tended to be less frequent among those who were unable to continue treatment, and oral care tended to be more frequent among those who were unable to continue treatment.

Table 3 shows the changes in the oral status of 49 participants who continued treatment. After 6 months, the number of carious teeth, number of mobile teeth, number of teeth, and proportion of teeth that required extraction decreased significantly. In terms of OHAT, there were no significant changes in the “tongue” and “dental pain” sub-items; however, the total score, lips, gums and tissues, saliva, natural teeth, dentures, and oral cleanliness significantly decreased. The number of functional teeth increased significantly. In terms of oral hygiene, there were no significant differences in the proportion of rinsing ability and participants who needed assistance after 6 months.

Table 4 shows the results of the Cox proportional hazards analysis on the factors at the time of the first visit that were related to treatment continuation. In the multivariate model that was adjusted for age and care level, the Barthel Index and MNA-SF were significantly lower for those who were unable to continue treatment, as well as significant difficulty rinsing. IADL also tended to decline, and OHAT tongue score tended to be ≥ 1 point.

Discussion

This prospective study is the first to clarify the dental treatment outcome and factors affecting treatment discontinuation in older adults who receive home medical care (i.e., older adults with many medical needs). The dental treatments performed were oral care, dysphagia rehabilitation, prosthetic treatment, extraction, and restorative treatment. The oral health status of participants who could continue treatment improved after 6 months. On the other hand, 31.9% of the patients were unable to continue DDC after 6 months due to the deterioration of their general condition. Factors that impeded treatment continuation were decreased ADL, decreased nutritional status, and difficulty in rinsing. Changes in the tongue such as tongue coating was also tended to be a factor.

Among the participants in this study, 97.2% received dental treatment. The dental treatment conducted included oral care, dysphagia rehabilitation, denture treatment, tooth extraction, and restorative treatment, all of which contributed to the improvement of oral health condition after 6 months. The need for dental treatment among older adults with reduced functional status is high, with 72% to 90% or more in hospitals [30, 31], facilities [32,33,34], and older adults who receive home medical care with stable functional status [35]. The actual dental treatment is generally prosthesis (69–96.4%) and oral care (80–90.6%) [36, 37]. Among the dentists who actively performed DDC, dysphagia rehabilitation was also reported as a common treatment (64.5%) [37]. The details of the dental treatment are affected by the patient’s (family’s) understanding and barriers experienced by the dentist [36, 38, 39] (lack of knowledge, time, low remuneration, infection control, emergency medicine, lack of appropriate equipment, difficulty in transporting equipment), and participant's dependence. Therefore, we believe that differences arise depending on the setting. This institution specializes in DDC for older adults, including dysphagia rehabilitation. Thus, at the very least, barriers on the part of dentists had a low impact on treatment outcomes. In addition, in cooperation with the referring physician, it was possible to grasp and respond to the general condition; hence, almost all patients were treated according to their needs and demands.

There was a relationship between treatment continuation and dental treatment details. Patients who were unable to continue treatment received less tooth extraction and instead tended to receive prosthetic treatment and more oral care. At baseline, there were no differences in the presence of teeth that require extraction, state of prosthesis, and oral hygiene status. Therefore, the reasons for the difference in treatment details were (1) the number of days until the participant's death, hospital admission, and institutionalization (i.e., physical barriers), and (2) oral care that was less burdensome to the participant was prioritized over aggressive dental treatment, apart from the necessary oral care (i.e., general condition barriers).

Dental treatment improved the oral health status of participants who continued treatment. There have been reports that show the effectiveness of dental treatment in older adults who receive home medical care. Studies have reported that oral hygiene programs and education improved oral hygiene [8,9,10] and multidisciplinary awareness [10, 40], restored occlusal support [12], and improved the oral intake function of parenteral users through dysphagia rehabilitation [11], However, there have been no reports that compared before and after extraction and caries treatment or showed the therapeutic effect using a comprehensive oral evaluation tool, such as OHAT, which was used in this study. Since OHAT is an oral health evaluation tool that can be shared across different professions [26], the results of this study may contribute to the transmission of dental treatment effects to medical care workers who are involved in home visits.

On the contrary, while there was a reduction in the number of carious teeth and those requiring extraction following treatment, some teeth persisted even after 6 months. We attribute this persistence to certain participants who could initiate but were unable to complete active treatment within the 6-month timeframe due to specific barriers encountered by older adults receiving home medical care. These barriers include their overall health condition, coordination with other medical and nursing care services, as well as considerations regarding the wishes of the patient and their family.

Factors that impeded treatment continuation were decreased ADL, decreased nutritional status, difficulty in rinsing, and changes in the tongue. In Japan, decreased ADL and nutritional status have been identified as risk factors for death at home and interruption of home medical care [41, 42]. Rinsing ability requires many difficult functions, such as fluid and instrument management, pharyngeal function, oral pressure control, saliva control skills, and coordination with respiratory function [43]. It is impaired by cognitive, oral, and swallowing dysfunction [44, 45]. The tongue is a well-known factor that indicates oral functions. Apart from poor hygiene, tongue changes, especially tongue coating, indicate decreased tongue motility [46, 47]. These changes are widely observed in older adults. Tongue hygiene and function are related to respiratory function, swallowing function, nutritional status, physical function, and life prognosis, among others [47, 48]. Therefore, in addition to ADL and nutritional status, rinsing ability and tongue changes are novel in extracting oral factors that may impede home medical care in older adults who receive such services.

However, even in participants who were able to continue treatment, there was no change in rinsing ability and tongue condition even after 6 months of dental treatment. The participants in this study had poor oral health, and approximately 40% of participants required assistance in cleaning their oral status. As such, since it is necessary to pay attention to meals, these functions (rinsing ability and tongue function) may be inevitably difficult to improve. The maintenance of residual functions and well-being are important for older adults who have high medical needs and are in the final stages of life. Although no improvement in functions was observed, the fact that they did not deteriorate can be seen as a positive result.

This study has some limitations. First, generalizability may be limited since the participants of this study were visiting patients at a single clinic. Second, selection bias may have affected the results since DDC was only recommended by the physicians, and the patients only agreed to it. However, this indicates that it is difficult to start and continue DDC unless patients and their families are aware of oral problems. Third, the sample size was small, and the presence of β errors may have affected the results. Since it is difficult to secure participants for research on older adults receiving home medical care [49, 50], this study, which secured approximately 70 participants, has clinical significance. Thus, there is a need to increase the sample size.

Conclusions

After 6 months, dental treatment in DDC improved the oral health status of older adults who receive home medical care. On the other hand, 31.9% were unable to continue treatment due to the deterioration of their general condition within 6 months of dental treatment. Factors that impeded treatment continuation were decreased ADL, decreased nutritional status, difficulty in rinsing, and changes in the tongue such as tongue coating.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy restrictions.

References

Peres MA, Macpherson LMD, Weyant RJ, Daly B, Venturelli R, Mathur MR, et al. Oral diseases: a global public health challenge. Lancet. 2019;394(10194):249–60.

Liu F, Song S, Ye X, Huang S, He J, Wang G, et al. Oral health-related multiple outcomes of holistic health in elderly individuals: an umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Front Public Health. 2022;10:1021104.

Hama K, Iwasa Y, Ohara Y, Iwasaki M, Ito K, Nakajima J, et al. Pneumonia incidence and oral health management by dental hygienists in long-term care facilities: a 1-year prospective multicentre cohort study. Gerodontology. 2022;39(4):374–83.

Kenny A, Dickson-Swift V, Chan CKY, Masood M, Gussy M, Christian B, et al. Oral health interventions for older people in residential aged care facilities: a protocol for a realist systematic review. BMJ Open. 2021;11(5):e042937.

Ozaki K, Teranaka S, Tohara H, Minakuchi S, Komatsumoto S. Oral management by a full-time resident dentist in the hospital ward reduces the incidence of pneumonia in patients with acute stroke. Int J Dent. 2022;2022:6193818.

Yoshimi K, Nakagawa K, Momosaki R, Yamaguchi K, Nakane A, Tohara H. Effects of oral management on elderly patients with pneumonia. J Nutr Health Aging. 2021;25(8):979–84.

Shiraishi A, Yoshimura Y, Wakabayashi H, Tsuji Y, Yamaga M, Koga H. Hospital dental hygienist intervention improves activities of daily living, home discharge and mortality in post-acute rehabilitation. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2019;19(3):189–96.

Tuuliainen E, Nihtilä A, Komulainen K, Nykänen I, Hartikainen S, Tiihonen M, et al. The association of frailty with oral cleaning habits and oral hygiene among elderly home care clients. Scand J Caring Sci. 2020;34(4):938–47.

Ho BV, van der Maarel-wierink CD, de Vries R, Lobbezoo F. Oral health care services for community-dwelling older people with dementia: a scoping review. Gerodontology. 2022;40(3):288–98.

Weening-Verbree LF, Schuller AA, Zuidema SU, Hobbelen JSM. Evaluation of an oral care program to improve the oral health of home-dwelling older people. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(12):7251.

Furuya H, Kikutani T, Igarashi K, Sagawa K, Yajima Y, Machida R, et al. Effect of dysphagia rehabilitation in patients receiving enteral nutrition at home nursing care: a retrospective cohort study. J Oral Rehabil. 2020;47(8):977–82.

Kikutani T, Takahashi N, Tohara T, Furuya H, Tanaka K, Hobo K, et al. Relationship between maintenance of occlusal support achieved by home-visit dental treatment and prognosis in home-care patients—a preliminary study. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2022;22:976–81.

Yu CH, Wang YH, Lee YH, Chang YC. The implementation of domiciliary dental care from a university hospital: a retrospective review of the patients and performed treatments in central Taiwan from 2010 to 2020. J Dent Sci. 2022;17(1):96–9.

Yu CH, Chang YC. The implication of COVID-19 pandemic on domiciliary dental care. J Dent Sci. 2022;17(1):570–2.

Matsuda S, Muramatsu K, Hayashida K. Eligibility classification logic of the Japanese long term care insurance. Asian Pac J Dis Manag. 2011;5(3):65–74.

Mahoney FI, Barthel DW. Functional evaluation: the Barthel Index. Md State Med J. 1965;14:61–5.

Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist. 1969;9:179–86.

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–83.

de Groot V, Beckerman H, Lankhorst GJ, Bouter LM. How to measure comorbidity. A critical review of available methods. J Clin Epidemiol. 2003;56:221–9.

Kaiser MJ, Bauer JM, Ramsch C, Uter W, Guigoz Y, Cederholm T, et al. Validation of the Mini Nutritional Assessment short-form (MNA-SF): a practical tool for identification of nutritional status. J Nutr Health Aging. 2009;13:782–8.

Kunieda K, Ohno T, Fujishima I, Hojo K, Morita T. Reliability and validity of a tool to measure the severity of dysphagia: the Food Intake LEVEL Scale. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2013;46(2):201–6.

Matsuo K. Reliability and validity of the Japanese Version of the Oral Health Assessment Tool (OHAT-J). J Japan Soc Disabil Oral Health. 2024;372016:1.

Petersen PE, Ueda H. Oral health in ageing societies: integration of oral health and general health. Geneve: World Health Organization; 2006.

Miller SC. Textbook of periodontia: oral medicine.1943:91.

Moreira CH, Zanatta FB, Antoniazzi R, Meneguetti PC, Rösing CK. Criteria adopted by dentists to indicate the extraction of periodontally involved teeth. J Appl Oral Sci. 2007;15(5):437–41.

Chalmers JM, King PL, Spencer AJ, Wright FA, Carter KD. The oral health assessment tool—validity and reliability. Aust Dent J. 2005;50(3):191–9.

Rodrigues LG, Sampaio AA, da Cruz CAG, Vettore MV, Ferreira RC. A systematic review of measurement instruments for oral health assessment of older adults in long-term care facilities by nondental professionals. Gerodontology. 2023;40(2):148–60.

Maeda K, Mori N. Poor oral health and mortality in geriatric patients admitted to an acute hospital: an observational study. BMC Geriatr. 2020;20(1):26.

Ogawa T, Koike M, Nakahama M, Kato S. Poor oral health is a factor that attenuates the effect of rehabilitation in older male patients with fractures. J Frailty Aging. 2022;11(3):324–8.

Peltola P, Vehkalahti MM, Wuolijoki-Saaristo K. Oral health and treatment needs of the long-term hospitalized elderly. Gerodontology. 2004;21(2):93–9.

Montal S, Tramini P, Triay JA, Valcarcel J. Oral hygiene and the need for treatment of the dependent institutionalized elderly. Gerodontology. 2006;23(2):67–72.

Wyatt CCL, Kawato T. Changes in oral health and treatment needs for elderly residents of long-term care facilities over 10 years. J Can Dent Assoc. 2019;84: i7.

Alshehri S. Oral health status of older people in residential homes in Saudi Arabia. Open J Stomatol. 2012;2:307–13.

Gerritsen PF, Cune MS, van der Bilt A, de Putter C. Dental treatment needs in Dutch nursing homes offering integrated dental care. Spec Care Dentist. 2011;31(3):95–101.

Gluzman R, Meeker H, Agarwal P, Patel S, Gluck G, Espinoza L, et al. Oral health status and needs of homebound elderly in an urban home-based primary care service. Spec Care Dentist. 2013;33(5):218–26.

Sweeney MP, Manton S, Kennedy C, Macpherson LM, Turner S. Provision of domiciliary dental care by Scottish dentists: a national survey. Br Dent J. 2007;202(9):E23.

Kamijo S, Sugimoto K, Oki M, Tsuchida Y, Suzuki T. Trends in domiciliary dental care including the need for oral appliances and dental technicians in Japan. J Oral Sci. 2018;60(4):626–33.

Bots-VantSpijker PC, Bruers JJM, Bots CP, Vanobbergen JN, De Visschere LM, de Baat C, et al. Opinions of dentists on the barriers in providing oral health care to community-dwelling frail older people: a questionnaire survey. Gerodontology. 2016;33(2):268–74.

Bots-VantSpijker PC, Vanobbergen JN, Schols JM, Schaub RM, Bots CP, de Baat C. Barriers of delivering oral health care to older people experienced by dentists: a systematic literature review. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2014;42(2):113–21.

Ho BV, van der Maarel-Wierink CD, Rollman A, Weijenberg RAF, Lobbezoo F. ‘Don’t forget the mouth!’: a process evaluation of a public oral health project in community-dwelling frail older people. BMC Oral Health. 2021;21(1):536.

Umegaki H, Asai A, Kanda S, et al. Risk factors for the discontinuation of home medical care among low-functioning older patients. J Nutr Health Aging. 2016;20(4):453–7.

Watanabe T, Matsushima M, Kaneko M, Aoki T, Sugiyama Y, Fujinuma Y. Death at home versus other locations in older people receiving physician-led home visits: a multicenter prospective study in Japan. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2022;22(12):1005–12.

Arai K, Sumi Y, Uematsu H, Miura H. Association between dental health behaviours, mental/physical function and self-feeding ability among the elderly: a cross-sectional survey. Gerodontology. 2003;20(2):78–83.

Sato E, Hirano H, Watanabe Y, Edahiro A, Sato K, Yamane G, et al. Detecting signs of dysphagia in patients with Alzheimer’s disease with oral feeding in daily life. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2014;14(3):549–55.

Shirobe M, Edahiro A, Motokawa K, Morishita S, Ohara Y, Motohashi Y, et al. Association between dementia severity and oral hygiene management issues in older adults with Alzheimer’s disease: a cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(5):3841.

Minakuchi S, Tsuga K, Ikebe K, Ueda T, Tamura F, Nagao K, et al. Oral hypofunction in the older population: position paper of the Japanese Society of Gerodontology in 2016. Gerodontology. 2018;35(4):317–24.

Izumi M, Akifusa S. Tongue cleaning in the elderly and its role in the respiratory and swallowing functions: benefits and medical perspectives. J Oral Rehabil. 2021;48(12):1395–403.

Nagano A, Ueshima J, Tsutsumiuchi K, Inoue T, Shimizu A, Mori N, et al. Effect of tongue strength on clinical outcomes of patients: a systematic review. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2022;102:104749.

Hoeksema AR, Peters LL, Raghoebar GM, Meijer HJA, Vissink A, Visser A. Health and quality of life differ between community living older people with and without remaining teeth who recently received formal home care: a cross sectional study. Clin Oral Investig. 2018;22(7):2615–22.

Ho BV, Weijenberg RAF, van der Maarel-Wierink CD, Visscher CM, van der Putten GJ, Scherder EJA, et al. Effectiveness of the implementation project “Don’t forget the mouth!” of community dwelling older people with dementia: a prospective longitudinal single-blind multicentre study protocol (DFTM!). BMC Oral Health. 2019;19:91.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all staff members and participants of the study. This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI (Grant No. 20K18813).

Funding

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI (Grant No. 20K18813).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Kumi Tanka: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, visualization, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing. Tomokazu Tominaga: methodology, project administration; writing—original draft; and writing—review and editing. Takeshi Kikutani: conceptualization, methodology, supervision, project administration, validation, writing—original draft; and writing—review and editing. Taeko Sakuda: investigation, writing—review and editing. Hiroyasu Furuya: investigation, writing—review and editing. Yuko Tanaka: investigation, writing—review and editing. Yuka Komagata: investigation, writing—review and editing. Arato Mizukoshi: investigation, writing—review and editing. Yoko Ichikawa: investigation, writing—review and editing. Maiko Ozeki: investigation, writing—review and editing. Noriaki Takahashi: investigation, writing—review and editing. Fumiyo Tamura: project administration, funding acquisition, validation, writing—review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors report that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the ethics review board of Nippon Dental University School of Life Dentistry (Approval No. NDU-T2020-13).

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from the participants or their families if obtaining consent from the participant was difficult. This study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Tanaka, K., Kikutani, T., Takahashi, N. et al. A prospective cohort study on factors related to dental care and continuation of care for older adults receiving home medical care. Odontology (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10266-024-00984-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10266-024-00984-4