Abstract

Background

Major hepatectomy is associated with significant morbidity and mortality rates, particularly in patients aged more than 70 years. This study assessed whether physical indicators, such as sarcopenia and visceral fat amount, could predict morbidity and mortality after major hepatectomy.

Methods

The study enrolled 144 patients who underwent curative major hepatectomy. Skeletal muscle and visceral fat amount at the third lumbar vertebra (L3) in the inferior direction were quantified using enhanced computed tomography scans. The patients were divided into two subgroups, with and without sarcopenia, based on median skeletal muscle mass in men and women (43.2 cm2/m2 in men; 35.3 cm2/m2 in women).

Results

The study included 108 men and 36 women, with median skeletal muscle tissue of 43.2 and 35.3 cm2/m2, respectively. The mortality rate was significantly higher in patients with than without sarcopenia [seven cases (9.7 %), one case (1.4 %), respectively; P = 0.021], whereas liver-related morbidity and mortality rates were similar. In patients aged >70 years, the morbidity, liver dysfunction-related morbidity, and mortality rates were significantly higher in patients with than without sarcopenia (P < 0.05 each). In contrast, surgical outcomes were similar in patients with high and low visceral fat amounts.

Conclusions

Sarcopenia was a risk factor for postoperative complications after major hepatectomy, particularly in elderly patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Although advances in multimodal treatment options, such as radiofrequency ablation, interventional radiology, and chemotherapy, have improved survival rate in patients with liver cancer [1–3], hepatic resection still provides the best hope of cure [4]. Major hepatectomy, however, is still associated with significant morbidity (12.9–47.1 % [5–9]) and mortality (2.6–7.4 % [5–10]) rates, despite advances in surgical techniques and perioperative care. Postoperative complications lead to not only prolonged hospital stays but also greater medical costs, and, possibly, poorer long-term survival [11, 12]. Accurate assessments of future remnant liver function are crucial in avoiding or minimizing postoperative complications. However, some patients experience unexpected postoperative complications, despite a careful preoperative workup, suggesting that an alternative approach, considering not only liver function but general patient condition, is required to prevent morbidity after hepatectomy. Moreover, the number of elderly patients who undergo major hepatectomy is increasing, and this population is more likely to suffer from relevant disorders, such as cardiac or pulmonary dysfunction and diabetes mellitus, that may affect postoperative outcomes [13]. Indeed, the mortality rate following major hepatectomy was found to be 11.1 % in patients aged more than 70 years compared with 3.6 % in younger patients [14].

Aging results in a progressive loss of muscle mass and strength, so-called sarcopenia. Sarcopenia may cause functional impairment, physical disability, and even mortality and has been associated with poorer long-term outcomes in cancer patients [15–20]. Sarcopenia has been reported to be a robust predictor of postoperative complications of general anesthesia [21, 22]. The prevalence of sarcopenia continues to increase worldwide and has been associated with the increase in the number of elderly persons.

Aging and physical disability have also been associated related with increases in fat mass, particularly visceral fat, which is important in the development of metabolic syndrome and other cardiovascular disease. Visceral fat amount has been reported to be associated with an increased incidence of many types of cancer [23]. Moreover, obesity itself has been reported to affect outcomes of abdominal surgery [24, 25].

The clinical significance of sarcopenia and visceral fat amount in surgical outcomes after hepatectomy remains unclear. We therefore analyzed whether sarcopenia or visceral fat amount could predict morbidity, liver-related morbidity, and overall mortality after major hepatectomy.

Patients and methods

Study subjects

A total of 144 consecutive patients who underwent major hepatectomy (three or more Couinaud’s segments) at Kumamoto University Hospital (Kumamoto, Japan) between January 2007 and December 2013 were enrolled in this study. Patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. Of these patients, 44 (30.1 %) underwent preoperative portal vein embolization before major hepatectomy. Perioperative data were prospectively collected, and the association between objective factors of physical condition (such as sarcopenia and visceral fat amount) and surgical outcomes after major hepatectomy were retrospectively analyzed. Additionally, we also analyzed their impact in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) patients only. These patient characteristics are shown in Table S1.

Assessment of adipose and skeletal muscle tissue

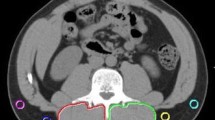

All patients underwent preoperative multi-slice contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) (slice thickness, 2.5 mm). A transverse CT image of each scan at the third lumbar vertebra (L3) in the inferior direction was used to calculate the amounts of adipose and skeletal muscle tissues [20]. The areas of skeletal muscle mass and visceral fat amount were measured by the Synapse Vincent system. Skeletal muscle was identified and quantified by Hounsfield unit (HU) thresholds of −29 to +150 (water is defined as 0 HU, air as 1000 HU). The areas of visceral fat were calculated by measuring pixels with densities in the range of −190 to −30 HU [26, 27]. Briefly, visceral fat amounts were quantified in several muscles, including the psoas, erector spine, quadratus lumborum, transversus abdominis, rectus abdominis, and external and internal oblique abdominal muscles (Fig. 1). The cross-sectional area of each segment was normalized by height (cm2/m2). Because sarcopenia criteria are different between Japanese and Western people, we divided the patients into two subgroups with and without sarcopenia based on the median skeletal muscle mass in men and women (43.2 cm2/m2 in men and 35.3 cm2/m2 in women). Cutoff values for visceral fat amount were determined as 103 cm2 for men and 69 cm2 for women, which are recognized as measures of metabolic abnormalities in Japan [28].

Computed tomogram shows area of skeletal muscle mass (highlighted blue) and visceral fat amount (highlighted red) in L3 region. Areas of skeletal muscle mass and visceral fat amount were measured using the Synapse Vincent system. Skeletal muscle was identified and quantified by Hounsfield unit (HU) thresholds of −29 to +150. Areas of visceral fat were calculated by measuring pixels with densities in the range of −190 to −30 HU

Definition of surgical outcomes

The main surgical outcomes in the present study were morbidity, including liver-related morbidity, and mortality after major hepatectomy. Complications were categorized using the modified Clavien classification system [29, 30]. Morbidity (i.e., serious complications) was defined as grade III or greater (IV and V). Liver-related morbidity was defined as a serum bilirubin level >3.0 mg/dl (50 μmol/l) and/or a prothrombin time index <50 % of the normal value on or after postoperative day 5, along with clinical symptoms, such as refractory ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, and hepatorenal syndrome, requiring intensive care treatment and defined as grade C post-hepatectomy liver failure by the International Study Group of Liver Surgery [9, 31]. Mortality was defined as any death that occurred during the same hospital stay or within 3 months after major hepatectomy.

Statistical methods

Continuous variables are expressed as median (range) unless otherwise stated and compared using Student’s t tests. We constructed a multivariate model to compute a hazard ratio (HR) according to morbidity, liver-related morbidity, and mortality. Cox model odds ratios (OR) with 95 % confidence intervals (CI) were calculated. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using JMP (Version 9; SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) software.

Results

Perioperative and postoperative outcomes

Of the 144 patients, 108 (75 %) were male and 36 (25 %) were female. The details of peri- and postoperative outcomes are described in Table 1. Serious postoperative complications, defined as grade III or greater (IV and V), occurred in 43 of the 144 patients (30 %). Liver-related morbidity occurred in 11 patients (7.6 %) and perioperative death in 8 (5.6 %), all of whom died of liver failure. Operative methods and diagnosis are shown in Table S1 (supporting information).

Sarcopenia and visceral fat amounts

The median amounts of skeletal muscle tissue were 43.2 cm2/m2 in men and 35.3 cm2/m2 in women. Using cutoff values of 103 cm2 for men and 69 cm2 for women, 69 patients (47.9 %) had high amounts of visceral fat. Comparative analysis showed that patients with sarcopenia and a low amount of visceral fat amount had a significantly lower body mass index (BMI) (Table 1). There were correlations among total skeletal muscle, BMI, and visceral fat amount (Fig. 2). Other factors such as age, sex, hepatitis, preoperative therapy, tumor size, number of tumors, tumor markers, and diagnosis were not related to the presence of sarcopenia or the amount of visceral fat. Additional analysis of the clinical significance of sarcopenia and visceral fat amount was performed in elderly patients aged more than 70 years. In this group, patients with sarcopenia and low visceral fat amount were significantly older and had significantly lower BMI (Table 2).

Impact of sarcopenia and visceral fat amount on surgical outcomes after major hepatectomy

The impact of sarcopenia or visceral fat amount on surgical outcomes after major hepatectomy was evaluated using the Pearson’s chi-squared test (χ2) (Table 1). The mortality rate was significantly higher in patients with sarcopenia than without sarcopenia (P = 0.021), whereas morbidity and liver-related morbidity rates did not differ significantly (P = 0.58, P = 0.11 respectively) (Table 1; Fig. S1A). In patients aged more than 70 years, the morbidity (P = 0.046), liver-related morbidity (P = 0.025), and mortality (P = 0.0018) rates were significantly higher in patients with than without sarcopenia. (Table 2, Figure S1B). In contrast, morbidity (P = 0.5), liver-related morbidity (P = 0.9), and mortality (P = 0.37) were similar in patients with high and low amounts of visceral fat (Table 1), even in the subgroup of patients aged more than 70 years (Table 2). Operation time, however, was significantly shorter in patients with low than high visceral fat amounts.

In univariable analysis, significant risk factors for mortality in all patients were low skeletal muscle mass, presence of HCV infections, long operative time, and high blood loss. In multivariable analysis, low skeletal muscle mass was identified as the risk factor in mortality (HR 4.3, P = 0.038) (Table 3).

In patients aged more than 70 years, the low skeletal muscle mass was a significant risk factor for morbidity and liver-related morbidity and mortality in univariable analysis. In multivariable analysis, low skeletal muscle mass was identified as the risk factor in all complications (morbidity: HR 4.6, P = 0.032; liver-related morbidity: HR 6.54, P = 0.011; mortality: HR 6.54, P = 0.011) (Table 4).

Impact of sarcopenia and visceral fat amount on surgical outcomes after major hepatectomy in HCC patients

We also analyzed the impact of these factors in HCC patients only. The liver-related morbidity and mortality rates was significantly higher in patients with sarcopenia than without sarcopenia (P = 0.024, P = 0.01 respectively), whereas the morbidity rate did not differ significantly (P = 0.46). In patients aged above 70 years, all rates were also significantly higher in patients with than without sarcopenia (P = 0.035, P = 0.027, P = 0.0051, respectively) (Table S2). The amount of visceral fat was not associated with morbidity, liver-related morbidity, and mortality rates in HCC patients (Table S2). We also examined univariable and multivariable analysis in all complications. In multivariable analysis, low skeletal muscle mass was identified as the risk factor for liver-related morbidity (HR 14.9, P = 0.0001) and mortality (HR 9.45, P = 0.0021) in HCC patients (Table S3), and in HCC patients aged more than 70 years (morbidity: HR 5.2, P = 0.023; liver-related morbidity: HR 8.5, P = 0.0035; mortality: HR 6.73, P = 0.0095; Table S4).

Discussion

The rates of sarcopenia are increasing in elderly patients who undergo major surgery, including hepatectomy. This study showed that sarcopenia is a useful predictive factor of mortality in patients undergoing major hepatectomy. Sarcopenia was a powerful predictor of postoperative complications, including morbidity, liver-related morbidity, and mortality, following major hepatectomy, especially in patients aged 70 years and older.

Sarcopenia is associated with aging, inactivity, and with a series of chronic diseases. Depletion of muscle mass was found to be a risk factor for perioperative infection, and sarcopenia was associated with increased length of hospital stay and requirements for prolonged rehabilitation [32]. In addition, sarcopenia was strongly associated with an increased risk of major postoperative complications in patients who underwent hepatectomy for colorectal liver metastases [21]. As such, sarcopenia may be an objective measurement of frailty that might help predict the risk of perioperative morbidity. This study also showed that sarcopenia was significantly associated with postoperative complications (liver-related morbidity and mortality) in HCC patients (Table S2). Harimoto et al. [20] described the significant relationship between sarcopenia and long-term outcome in HCC patients with hepatic resection. Skeletal muscle was recently identified as an endocrine organ [33]. The cytokines and other peptides that are produced, expressed, and released by muscle fibers might influence the short-term and long-term outcome of HCC patients.

Selecting appropriate candidates for liver resection is therefore crucial to maximize the benefits derived from surgery [34, 35]. Hepatectomy is considered a high-risk operation in elderly patients, for both postoperative morbidity and mortality, because these patients already have low physical activity as a result of other diseases, including cardiac, pulmonary, and renal dysfunction and metabolic diseases [36, 37]. Sarcopenia may therefore be useful for identifying patients with low physical activity who are unable to tolerate major hepatectomy.

Several recent studies have reported that high visceral fat amount is associated with postoperative complications in patients with gastric and colon cancer [38, 39]. In contrast, BMI and visceral fat amount did not correlate with postoperative complications after pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic adenocarcinoma [40]. Moreover, obesity was not a risk factor for postoperative complications or mortality in patients after hepatic resection [25, 41]. In the present study, however, there were significant correlations between total skeletal muscle and visceral fat amount; the presence of high visceral fat amount did not have an effect on surgical outcomes, except for operation time, after major hepatectomy. We think that this is because Japanese have less visceral fat than Western people.

The limitations of this study are that it is a retrospective study. A further prospective study is required to confirm our results.

In conclusion, sarcopenia was a risk factor for mortality after major hepatectomy. In elderly patients aged more than 70 years, sarcopenia was a powerful and useful indicator of postoperative complications, including morbidity, liver-related morbidity, and mortality, after major hepatectomy. In contrast, the amount of visceral fat did not affect any surgical outcomes except for operation time.

Change history

28 July 2017

An erratum to this article has been published.

References

Aldrighetti L, Arru M, Caterini R et al (2003) Impact of advanced age on the outcome of liver resection. World J Surg 27:1149–1154

Cho SW, Steel J, Tsung A et al (2011) Safety of liver resection in the elderly: how important is age? Ann Surg Oncol 18:1088–1095

Liu L, Chen H, Wang M et al (2014) Combination therapy of sorafenib and TACE for unresectable HCC: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 9:e91124

Fong Y, Brennan MF, Cohen AM et al (1997) Liver resection in the elderly. Br J Surg 84:1386–1390

Palavecino M, Kishi Y, Chun YS et al (2010) Two-surgeon technique of parenchymal transection contributes to reduced transfusion rate in patients undergoing major hepatectomy: analysis of 1,557 consecutive liver resections. Surgery (St. Louis) 147:40–48

Reddy SK, Barbas AS, Turley RS et al (2011) A standard definition of major hepatectomy: resection of four or more liver segments. HPB (Oxf) 13:494–502

Reddy SK, Barbas AS, Turley RS et al (2011) Major liver resection in elderly patients: a multi-institutional analysis. J Am Coll Surg 212:787–795

Yang T, Zhang J, Lu JH et al (2011) Risk factors influencing postoperative outcomes of major hepatic resection of hepatocellular carcinoma for patients with underlying liver diseases. World J Surg 35:2073–2082

Rahbari NN, Garden OJ, Padbury R et al (2011) Posthepatectomy liver failure: a definition and grading by the International Study Group of Liver Surgery (ISGLS). Surgery (St. Louis) 149:713–724

Andreou A, Vauthey JN, Cherqui D et al (2013) Improved long-term survival after major resection for hepatocellular carcinoma: a multicenter analysis based on a new definition of major hepatectomy. J Gastrointest Surg 17:66–77 (discussion p. 77)

Laurent C, Sa Cunha A, Couderc P et al (2003) Influence of postoperative morbidity on long-term survival following liver resection for colorectal metastases. Br J Surg 90:1131–1136

Vigano L, Ferrero A, Tesoriere RL et al (2008) Liver surgery for colorectal metastases: results after 10 years of follow-up. Long-term survivors, late recurrences, and prognostic role of morbidity. Ann Surg Oncol 15:2458–2464

Mastoraki A, Tsakali A, Papanikolaou IS et al (2014) Outcome following major hepatic resection in the elderly patients. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol 38:462–466

Ezaki T, Yukaya H, Ogawa Y (1987) Evaluation of hepatic resection for hepatocellular carcinoma in the elderly. Br J Surg 74:471–473

Tan BH, Birdsell LA, Martin L et al (2009) Sarcopenia in an overweight or obese patient is an adverse prognostic factor in pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res 15:6973–6979

van Vledder MG, Levolger S, Ayez N et al (2012) Body composition and outcome in patients undergoing resection of colorectal liver metastases. Br J Surg 99:550–557

Sabel MS, Lee J, Cai S et al (2011) Sarcopenia as a prognostic factor among patients with stage III melanoma. Ann Surg Oncol 18:3579–3585

Montano-Loza AJ, Meza-Junco J, Prado CM et al (2012) Muscle wasting is associated with mortality in patients with cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 10:166–173 (173–e161)

Englesbe MJ, Patel SP, He K et al (2010) Sarcopenia and mortality after liver transplantation. J Am Coll Surg 211:271–278

Harimoto N, Shirabe K, Yamashita YI et al (2013) Sarcopenia as a predictor of prognosis in patients following hepatectomy for hepatocellular carcinoma. Br J Surg 100:1523–1530

Peng PD, van Vledder MG, Tsai S et al (2011) Sarcopenia negatively impacts short-term outcomes in patients undergoing hepatic resection for colorectal liver metastasis. HPB (Oxf) 13:439–446

Makary MA, Segev DL, Pronovost PJ et al (2010) Frailty as a predictor of surgical outcomes in older patients. J Am Coll Surg 210:901–908

Renehan AG, Tyson M, Egger M et al (2008) Body-mass index and incidence of cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective observational studies. Lancet 371:569–578

Merkow RP, Bilimoria KY, McCarter MD, Bentrem DJ (2009) Effect of body mass index on short-term outcomes after colectomy for cancer. J Am Coll Surg 208:53–61

Itoh S, Ikeda Y, Kawanaka H et al (2012) The effect of overweight status on the short-term and 20-y outcomes after hepatic resection in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. J Surg Res 178:640–645

Yoshizumi T, Nakamura T, Yamane M et al (1999) Abdominal fat: standardized technique for measurement at CT. Radiology 211:283–286

Mitsiopoulos N, Baumgartner RN, Heymsfield SB et al (1998) Cadaver validation of skeletal muscle measurement by magnetic resonance imaging and computerized tomography. J Appl Physiol 85(1):115–122

Kashihara H, Lee JS, Kawakubo K et al (2009) Criteria of waist circumference according to computed tomography-measured visceral fat area and the clustering of cardiovascular risk factors. Circ J 73:1881–1886

Clavien PA, Barkun J, de Oliveira ML et al (2009) The Clavien–Dindo classification of surgical complications: five-year experience. Ann Surg 250:187–196

Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA (2004) Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg 240:205–213

Paugam-Burtz C, Janny S, Delefosse D et al (2009) Prospective validation of the “fifty-fifty” criteria as an early and accurate predictor of death after liver resection in intensive care unit patients. Ann Surg 249:124–128

Lieffers JR, Bathe OF, Fassbender K et al (2012) Sarcopenia is associated with postoperative infection and delayed recovery from colorectal cancer resection surgery. Br J Cancer 107:931–936

Pedersen BK, Febbraio MA (2012) Muscles, exercise and obesity: skeletal muscle as a secretory organ. Nat Rev Endocrinol 8:457–465

Aldrighetti L, Arru M, Catena M et al (2006) Liver resections in over-75-year-old patients: surgical hazard or current practice? J Surg Oncol 93:186–193

Adam R, Frilling A, Elias D et al (2010) Liver resection of colorectal metastases in elderly patients. Br J Surg 97:366–376

Nishikawa H, Kimura T, Kita R et al (2013) Treatment for hepatocellular carcinoma in elderly patients: a literature review. J Cancer 4:635–643

Koperna T, Kisser M, Schulz F (1998) Hepatic resection in the elderly. World J Surg 22:406–412

Sugisawa N, Tokunaga M, Tanizawa Y et al (2012) Intra-abdominal infectious complications following gastrectomy in patients with excessive visceral fat. Gastric Cancer 15:206–212

Cecchini S, Cavazzini E, Marchesi F et al (2011) Computed tomography volumetric fat parameters versus body mass index for predicting short-term outcomes of colon surgery. World J Surg 35:415–423

Gaujoux S, Torres J, Olson S et al (2012) Impact of obesity and body fat distribution on survival after pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol 19:2908–2916

Saunders JK, Rosman AS, Neihaus D et al (2012) Safety of hepatic resections in obese veterans. Arch Surg 147:331–337

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

An erratum to this article is available at https://doi.org/10.1007/s10147-017-1163-5.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

About this article

Cite this article

Higashi, T., Hayashi, H., Taki, K. et al. Sarcopenia, but not visceral fat amount, is a risk factor of postoperative complications after major hepatectomy. Int J Clin Oncol 21, 310–319 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10147-015-0898-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10147-015-0898-0