Abstract

The cancer registry is an essential part of any rational program of evidence-based cancer control. The cancer control program is required to strategize in a systematic and impartial manner and efficiently utilize limited resources. In Japan, the National Clinical Database (NCD) was launched in 2010. It is a nationwide prospective registry linked to various types of board certification systems regarding surgery. The NCD is a nationally validated database using web-based data collection software; it is risk adjusted and outcome based to improve the quality of surgical care. The NCD generalizes site-specific cancer registries by taking advantage of their excellent organizing ability. Some site-specific cancer registries, including pancreatic, breast, and liver cancer registries have already been combined with the NCD. Cooperation between the NCD and site-specific cancer registries can establish a valuable platform to develop a cancer care plan in Japan. Furthermore, the prognosis information of cancer patients arranged using population-based and hospital-based cancer registries can help in efficient data accumulation on the NCD. International collaboration between Japan and the USA has recently started and is expected to provide global benchmarking and to allow a valuable comparison of cancer treatment practices between countries using nationwide cancer registries in the future. Clinical research and evidence-based policy recommendation based on accurate data from the nationwide database may positively impact the public.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The cancer registry is an essential part of any rational program of evidence-based cancer control [1, 2]. This information can be used to monitor cancer patterns in certain regions and to formulate an effective cancer control plan [2]. In Japan, the government started promoting and supporting a cancer control plan based on the Cancer Control Act of 2006. Cancer registries in Japan are classified into three types—population-based, hospital-based, and site-specific cancer registries. Each registry plays an important role in the epidemiology, evaluation of patient care quality, and in providing clinically detailed information (Table 1); however, all three types have problems with poor standardization or incomplete follow-up [2].

The cancer control program is required to strategize in a systematic and impartial manner and efficiently utilize limited resources. The National Clinical Database (NCD) in Japan, which was launched in 2010 and commenced patient registration in January 2011, is a nationwide prospective registry linked to the surgical board certification system. The NCD systematically collects accurate data to develop a standardized surgery database for quality improvement and healthcare quality evaluation, considering the structure, process, and outcome [3]. Moreover, submitting cases to the NCD is a prerequisite for all member institutions of the surgical society, and only registered cases can be used for board certification. The NCD contains >1,200,000 surgical cases collected in 2011, and approximately 4,000 institutions were participating at the end of 2013. Detailed information on cancer, such as gastrointestinal, liver, pancreas, thyroid, and breast cancer is also collected in the NCD. The NCD generalizes site-specific cancer registries by taking advantage of their excellent organizing ability [4]. Some site-specific cancer registries, including pancreatic, breast, and liver cancer registries have already been combined with the NCD. Furthermore, it has also been promoted to cooperate with non-surgical fields.

Here, we summarize the current status of the NCD and site-specific cancer registries in conjunction with future perspectives for developing a cancer registration system.

Current status of the NCD

There was no nationwide clinical database for gastroenterological surgery for cancer treatment in Japan before 2006. The Japanese Society of Gastroenterological Surgery organized preliminary nationwide surveys in gastroenterological surgery in 2006 and 2007. These surveys, without using risk-adjustment techniques, indicated that hospital volume may influence the mortality rate after major gastroenterological surgery [5]. However, it was considered that upgraded analysis using risk-adjustment techniques should have been conducted to reveal the specific contribution of the variables. The NCD was established in 2010 as a general incorporated association in partnership with several clinical societies. The activities of the NCD primarily focus on providing the highest quality healthcare possible to patients and to the general public with the clinical setting serving as the driving force behind improvements [3, 4]. The NCD was developed in collaboration with the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS-NSQIP). The ACS-NSQIP is the first nationally validated database using web-based data collection software. It is risk adjusted and outcome based to improve the quality of surgical care [6]. Development of the NCD allows risk-adjusted analysis in Japan.

The NCD continuously recruits individuals to approve the input data from members of several departments in charge of annual cases as well as data entry officers, through a web-based data management system to assure the traceability of the data. Furthermore, the project managers consecutively and consistently validate the data by inspecting randomly chosen institutions. All variables, definitions, and inclusion criteria regarding the NCD are accessible to all the participating institutions from the website (http://www.ncd.or.jp/) and are also intended to support an e-learning system in order for participants to input consistent data. The NCD also provides answers to all queries regarding data entry (approximately 80,000 inquiries in 2011) and regularly includes some of the queries as frequently asked questions on the website.

In the gastrointestinal surgery section, all surgical cases are registered and require detailed input items for eight procedures representing the performance of surgery in each specialty (low anterior resection, right hemicolectomy, hepatectomy, total gastrectomy, partial gastrectomy, pancreatoduodenectomy, esophagectomy, and surgery for acute diffuse peritonitis). Risk models for predicting surgical outcome have been created for the mortality of each procedure [7–13]. A total of 120,000 cases collected from the eight procedures in 2011 were then analyzed in each procedure. Data were randomly assigned into two subsets that were split as follows—80 % for model development and 20 % for validation. The two sets of logistic models (30-day mortality and operative mortality) were constructed for dataset development using a step-wise selection of predictors. Potential independent variables included patient demographics, pre-existing comorbidities, preoperative laboratory values, and operative data. Furthermore, multiple significant risk factors were identified in each procedure—age, American Society of Anesthesiologists class, respiratory distress, body mass index, platelet count, Brinkman index, etc. As a performance parameter of the risk model, the C-indices of the 30-day and operative mortality calculated from all models were >0.7; in particular, the indices of total gastrectomy [11], right hemicolectomy [9], and surgery for acute diffuse peritonitis [13] were >0.8, suggesting that the area under the receiver operating characteristics curves results were good. This is considered as proof of the efficacy and reliability of these risk models. These models could be available for participating institutes and would be useful for benchmark performance and decision making by surgeons as well as informed consent for patients. The NCD is currently planning to provide feedback on severity-adjusted clinical performance through a web-based program. Real-time feedback through the web provides an opportunity to observe changes within facilities and shifts in clinical performance [3].

The benefits of the NCD for patients include their ability to receive high-quality healthcare through the improvement of the medical service—fewer complications, shorter hospital stay, and better outcomes. Patients can also select hospitals that suit their preferences by choosing among board-certified surgeons in a relevant field. The benefits for surgeons who use the NCD include receiving better data for more targeted decision-making and disciplined reports that provide performance information useful for surgery and the ability to identify one’s position among peers to allow strategic planning.

Current activities of site-specific cancer registries

The site-specific cancer registries in Japan are conducted by academic societies or research organizations specializing in cancers of different origin. Many institutes nationwide are included and collect detailed clinical information based on the general rules of the Japanese classification of cancer [2]. The first site-specific cancer registry was launched in 1952 to collect data about gynecological cancer. In the field of gastroenterological surgery, gastric cancer (1963), esophageal cancer (1965), and hepatic cancer (1965) registries were launched as pioneers in developing site-specific cancer registries; colorectal, pancreatic, and biliary cancer registries were established in the 1980s. Each registry has released the original investigation report based on the specificity of each site. In the Japan pancreatic cancer registry, >350 leading institutions voluntarily contributed their information and periodic follow-up. Several reports on the overall survival and prognostic factors of pancreatic cancer in Japan have been published. A continuous survey on pancreatic cancer could indicate that the improvement of the survival of patients with invasive cancer can be attributed to the introduction of effective chemotherapies, regionalization, and earlier diagnosis and treatment [14–16]. For instance, the Japanese Society for Cancer of the Colon and Rectum (JSCCR), a nationwide database, covers approximately 10 % of all patients with colorectal cancer in Japan [17]. The JSCCR provided important information in establishing general rules for the Japanese classification of colorectal cancer and published clinical guidelines for the treatment of colorectal cancer. It has been evaluated that the publication of the guidelines has accelerated the spread of surgical standards [18]. As described, site-specific cancer registries, which register in-depth information in contrast to population-based and hospital-based cancer registries, have played a major role in the development of the cancer treatment program.

In contrast, there are several limitations to site-specific cancer registries. First, incomplete follow-up data is a serious issue; the data collection system at the institute needs to be improved. Second, management infrastructure systems are unstable as a whole in site-specific cancer registries. Third, inadequate standardization in the registration procedure is present in these registries. Furthermore, the registration forms of each registry and even the basic parameters for cancer registration are different. As a whole, in site-specific cancer registries, the databases have a lower cover rate (number of registration/estimated morbidity) that is not a complete enumeration.

Cooperation with the NCD and site-specific cancer registries

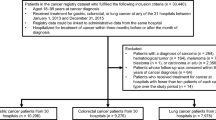

In order to solve several problems with site-specific cancer registries, it has been planned that the NCD generalizes site-specific cancer registries. Approximately 610,000 surgical cases were registered in the NCD in one year, including approximately 220,000 cases for the treatment of malignant tumors. The cover rate (number of registration/estimated morbidity) of the NCD is higher than that of site-specific cancer registries and glanularity is higher compared with that of other registries (Fig. 1). Breast cancer registration of the Japanese Breast Cancer Society was combined with the NCD in 2012. The Japan pancreatic cancer registry was also combined with the NCD in 2012. In addition, the liver cancer study group of Japan has just transferred its registration system into the NCD. Information required for the Japanese lung cancer registry is now mostly input into the NCD. At present, the NCD not only has the role of being a surgical database but also of being a database for several cancer registries. With cooperation between the NCD and high-precision site-specific cancer registries, it should be possible to build the basic framework to evaluate healthcare quality in the cancer control plan. Moreover, by assessing the performance of board-certified physicians for cancer treatment according to a guideline, it would be possible to identify the strategy towards the standardization of cancer treatment in Japan.

To assure the success of this cooperation, several issues should be solved. Data should be appropriately collected and should follow an exact baseline assessment. In particular, exhaustive and reliable information and a follow-up survey of a long-term prognosis are indispensable for the survival rate of cancer patients. The lack of long-term prognosis information has been an issue in site-specific cancer registries. The deviation of a participating institution and a registration case and the defect of a follow-up survey serve as bias; therefore, their influence on the interpretation of a result represents a major problem. The collection of the prognosis information in the NCD could allow the evaluation of a short-term prognosis on the basis of a 30-day postoperative outcome. A follow-up survey at 1, 5, and 10 years, based on the clinical feature of each cancer will be designed in the near future. The data quality and compatibility of the NCD are also continuously verified.

In contrast, several cancer registries and case registration systems are processed in parallel for a follow-up survey of cancer prognosis. Furthermore, the efficiency of data collection is also an important issue. Cooperation with the NCD and other cancer registries is essential to avoid inaccurate follow-up data. The government has started promoting and supporting the cancer registration plan based on the Cancer Registration Act of 2013. With this promotion and mandatory feedback to each department, prognosis information of cancer patients arranged by population- and hospital-based cancer registries can help in efficient data accumulation for the NCD. Fig. 2 shows the cooperation and integration of cancer registration systems.

Cooperation and integration of cancer registration systems. The prognostic information arranged by population-based and hospital based cancer registries are returned to the hospital which offered information. The information is then reflected through each hospital to the NCD and site-specific cancer registries

Future direction of the NCD and site-specific cancer registries

The coordination of a nationwide and advanced cancer registry, such as the combination between the NCD and site-specific cancer registry could positively impact society through their activities. In order to accomplish the same, the NCD needs to make progress by continuously evaluating this database. As mentioned above, the NCD is now planning to give feedback based on a rich store of clinical data. Similarly, in the cardiac surgery field, a web-based program provides feedback on severity-adjusted clinical performance [19]. The report is prepared by highlighting the patient characteristics. By utilizing the risk model, users would be able to predict the estimated mortality through entering the system on the web. ‘Surgical Risk Calculator’ developed by ACS-NSQIP (http://riskcalculator.facs.org/) is a similar feedback system. Furthermore, real-time and useful feedback is essential in developing a large-scale database. For instance, ACS-NSQIP indicates that surgical outcomes improve in participating hospitals; 66 % of hospitals showed improved risk-adjusted mortality and 82 % showed improved risk-adjusted complication rates. NSQIP hospitals appear to be avoiding substantial numbers of complications, improving care, and reducing costs [20]. The NCD is a platform of databases which would allow collaboration among institutes in Japan to provide an opportunity for clinical research based on a large-scale database and to produce novel evidence (Fig. 3).

International collaboration is important to evaluate the quality of medical care and to provide meaningful improvement. However, international comparisons of general surgery and outcomes using nationwide clinical registry data have not been accomplished. There is little information on the outcomes of Japanese patients undergoing gastroenterological surgery and its comparison with those of other countries. Furthermore, the application of predictive models for clinical risk stratification has not been internationally evaluated. The NCD in Japan collaborates with the ACS-NSQIP, which shares a similar goal of developing a standardized surgery database for quality improvement. The NCD implemented the same variables used by the ACS-NSQIP to facilitate international cooperative studies, which have recently started [21]. This collaboration is expected to provide a global benchmark and to evaluate and improve clinical care by comparing the treatment practices among countries using nationwide cancer registries.

Conclusions

Cooperation between the NCD and site-specific cancer registries can establish a valuable platform to develop a cancer care plan in Japan. Studies are in progress to improve the quality control of surgical procedures using the NCD. Furthermore, clinical research and evidence-based policy recommendations from accurate data of a nationwide database may positively impact the public.

References

Muir CS (1985) The International Association of Cancer Registries. The benefits of a worldwide network of tumor registries. Conn Med 49(11):713–717

Sobue T (2008) Current activities and future directions of the cancer registration system in Japan. Int J Clin Oncol 13(2):97–101

Miyata H, Gotoh M, Hashimoto H et al (2014) Challenges and prospects of a clinical database linked to the board certification system. Surg Today. doi:10.1007/s00595-013-0802-3

Gotoh M, Miyata H, Konno H (2014) Evolution and future of the National Clinical Database: feedback for surgical quality improvement. Nihon Geka Gakkai Zasshi 115(1):8–12

Suzuki H, Gotoh M, Sugihara K et al (2011) Nationwide survey and establishment of a clinical database for gastrointestinal surgery in Japan: Targeting integration of a cancer registration system and improving the outcome of cancer treatment. Cancer Sci 102(1):226–230

Cohen ME, Dimick JB, Bilimoria KY et al (2009) Risk adjustment in the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program: a comparison of logistic versus hierarchical modeling. J Am Coll Surg 209(6):687–693

Kenjo A, Miyata H, Gotoh M et al (2014) Risk stratification of 7,732 hepatectomy cases in 2011 from the National Clinical Database for Japan. J Am Coll Surg 218(3):412–422

Kimura W, Miyata H, Gotoh M et al (2014) A pancreaticoduodenectomy risk model derived from 8575 cases from a national single-race population (Japanese) using a web-based data entry system: the 30-day and in-hospital mortality rates for pancreaticoduodenectomy. Ann Surg 259(4):773–780

Kobayashi H, Miyata H, Gotoh M et al (2014) Risk model for right hemicolectomy based on 19,070 Japanese patients in the National Clinical Database. J Gastroenterol 49(6):1047–1055

Takeuchi H, Miyata H, Gotoh M, et al. (2014) A Risk Model for Esophagectomy Using Data of 5354 Patients Included in a Japanese Nationwide Web-Based Database. Ann Surg [Epub ahead of print]

Watanabe M, Miyata H, Gotoh M, et al. (2014) Total Gastrectomy Risk Model: Data From 20,011 Japanese Patients in a Nationwide Internet-Based Database. Ann Surg [Epub ahead of print]

Matsubara N, Miyata H, Gotoh M et al (2014) Mortality after common rectal surgery in Japan: a study on low anterior resection from a newly established nationwide large-scale clinical database. Dis Colon Rectum 57(9):1075–1081

Nakagoe T, Miyata H, Gotoh M, et al. (2014) Surgical risk model for acute diffuse peritonitis based on a Japanese nationwide database: an initial report of 30-day and operative mortality. Surg Today 2014 Sep 18 [Epub ahead of print]

Egawa S, Toma H, Ohigashi H et al (2012) Japan Pancreatic Cancer Registry; 30th year anniversary: Japan Pancreas Society. Pancreas 41(7):985–992

Matsuno S, Egawa S, Fukuyama S et al (2004) Pancreatic Cancer Registry in Japan: 20 years of experience. Pancreas 28(3):219–230

Yamamoto M, Ohashi O, Saitoh Y (1998) Japan Pancreatic Cancer Registry: current status. Pancreas 16(3):238–242

Konishi T, Watanabe T, Kishimoto J et al (2007) Prognosis and risk factors of metastasis in colorectal carcinoids: results of a nationwide registry over 15 years. Gut 56(6):863–868

Ishiguro M, Higashi T, Watanabe T, et al. (2014) Changes in colorectal cancer care in japan before and after guideline publication: a nationwide survey about D3 lymph node dissection and adjuvant chemotherapy. J Am Coll Surg 218(5):969–977.e961

Miyata H, Motomura N, Murakami A et al (2012) Effect of benchmarking projects on outcomes of coronary artery bypass graft surgery: challenges and prospects regarding the quality improvement initiative. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 143(6):1364–1369

Hall BL, Hamilton BH, Richards K et al (2009) Does surgical quality improve in the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program: an evaluation of all participating hospitals. Ann Surg 250(3):363–376

The 69th General Meeting of the Japanese Society of Gastroenterological Surgery, Special Program (2014)

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank all of the data managers and hospitals that participated in the NCD project for their great efforts in data entry. In addition, we wish to express appreciation to all the people and academies that cooperated in this project.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

About this article

Cite this article

Anazawa, T., Miyata, H. & Gotoh, M. Cancer registries in Japan: National Clinical Database and site-specific cancer registries. Int J Clin Oncol 20, 5–10 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10147-014-0757-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10147-014-0757-4