Abstract

Pain is an unpleasant and emotional subjective sensory experience that occurs during orthodontic procedures. Currently, LED phototherapy is an alternative to the use of laser light as analgesic agent due to similarity of response and lower cost. This case-control, quantitative, qualitative, and longitudinal study aimed to investigate the effect of IR LED phototherapy (λ846 ± 20 nm) in pain during the process of tooth separation during orthodontic treatment. After approval by the Institution Ethics Committee, 40 patients (30 female/10 male, 20–30 years old, average age 24.5 ± 2.6 years old) fulfilling the inclusion criteria entered the study and received a set of four visual analog scales (VAS) for scoring pain immediately, 48 h, 72 h, and 7 days after the insertion of the separating elastics. The patients were randomly distributed into two groups (experimental and control). The patients of experimental group received LED phototherapy (180 mW, 22 s, 4 J, 8 J/cm2, 0.36 W/cm2, spot of 0.5 cm2, spot diameter 0.8 cm) at the same times in which VAS was performed, and control patients were not irradiated. It was found that, in both groups, there was an increase in pain 48 h after insertion of the elastic tooth separator, decreasing 72 h after its installation and reached the lowest level of pain after 7 days. Comparison between groups showed that pain level in the LED group was always statistically significantly lower (p < 0.05), except for the time of installation (T1). The use of LED light was effective in significantly reducing the level of pain after insertion of the elastic tooth separators when compared to the control group.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Pain is a subjective unpleasant and emotional sensory experience [1]. The painful sensation depends on how it is interpreted by different individuals in response to a stimulus, and this perception varies according to age, gender, psychological condition, and cultural aspects [2]. The pain may be closely related to orthodontic procedures such as the placement of separating elastics, insertion of arch-wires and their subsequent activation, or bracket removal, as well as the effects of orthopedic forces. The soreness related to orthodontics reaches its peak after 6 h and tends to decline after 5 days [3].

Tooth movement causes an inflammatory response in the alveolar process, which triggers the pain. The inflammation is due, among other factors, to the creation of tension and compression zones in the periodontal ligament, which cause an inflammatory response associated with the release of chemical mediators, including histamine, prostaglandins, serotonin, and bradykinin that are linked to hyperalgesia [2, 3]. Compression forces in the periodontal tissues during orthodontic treatment also lead to ischemic necrosis and killing of cementoblasts and cells of the periodontal ligament [4, 5].

To control discomfort and pain during orthodontic treatment, different pharmacological and non-pharmacological methods, such as phototherapies, have been used [6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17]. Currently, LED phototherapy is available as an alternative to use of laser light mainly due to the similarity of the tissue responses as well as to its lower cost. However, few clinical studies [6, 8, 11, 14,15,16,17,18,19] using this phototherapy in dentistry have been conducted to investigate its effectiveness for pain control.

LEDs are monochromatic, non-coherent light-emitting devices featuring a wider wavelength band (λ360–950 nm) than lasers [18]. In both laser and LED irradiation, depending on its wavelength, the photons are absorbed by the cytochrome-C-oxidase or other photoreceptors (hemoglobin, fibrils proteins, water), which may lead to increased cell metabolism by stimulating the production of adenosine triphosphate (ATP). At the same time, an increase in the ion gradient (calcium ion, sodium/potassium, and ATP/ase) and an increased amount of nitric oxide are observed. The additional ATP is used to enhance and normalize many secondary processes, while normalizing cell function, resulting in tissue healing [4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18].

It is known that the application of orthodontic forces creates both compression and tension zones in the periodontal ligament that are followed by a cascade of reactions including changes in blood flow, the release of inflammatory cytokines (prostaglandins, substance P, histamine, encephalin, leukotrienes, etc.), the stimulation of afferent A delta and C nerve fibers, and the release of neuropeptides and hyperalgesia [19,20,21]. The pain symptom varies in both intensity and duration, and are mainly observed during early hours following the application of the forces. The peak of pain occurs between 18 and 36 h and reduces gradually in a week [19,20,21,22,23]. In recent years, the use of phototherapies attracted increasing attention of orthodontists as it reduces pain, stimulates bone repair, and shows no adverse effects [19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27]. Phototherapies can modify nerve conduction by affecting the synthesis, release, and metabolism of various neurochemicals, including endorphins and encephalin [18]. It has also been postulated that the effects of light on pain relief can be attributed to its inhibitory effects on nerve depolarization (especially C fibers) in the reactivation of enzymes targeted at pain-inductive factors, in the production of ATP, and in the reduction of prostaglandin levels [21, 24, 25].

Both laser and LED phototherapies exhibit similar effects in tissue in both healing and repair as well as in inflammation control and cell proliferation. However, LED phototherapy presents some advantages over the use of lasers such as its lower cost.

As LED phototherapy enhances the repair of periodontal tissue and mitigates inflammation after the application of orthodontic forces, it was hypothesized that its usage could, therefore, reduce pain [4, 26, 27].

This study aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of LED phototherapy to control pain resulting from the insertion of elastic separators during tooth movement.

Material and methods

Patients

Sampling

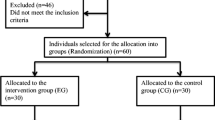

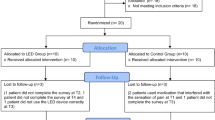

Forty adult individuals of both genders (30 females/10 males), aged between 20 and 30 years old (mean 24.5 years old), were selected among the patients of the Prof. José Martins Soares Édimo Center for Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics at the School of Dentistry of the Federal University of Bahia (UFBA). All patients were indicated for full orthodontic corrective treatment, requiring the installation of orthodontic bands with attachments on the molars. After signing a consent agreeing to participate on the trial, the selected patients entered the study.

Patient examination and inclusion/exclusion criteria

A single examiner, who also performed all clinical procedures, selected the patients. The inclusion criteria for participating as volunteers in the study were to be aged between 20 and 30 years; all teeth down to the second molars must have erupted and have contact points; and all subjects must sign a form of free and informed consent. The exclusion criteria were presence of systemic diseases, neurological or psychiatric disorders, and chronic pain; use of systemic medications (analgesics, antibiotics, anti-inflammatory drugs, antidepressants, and bisphosphonates); pathological conditions associated with teeth, gingiva, or periodontium; presence of restorations on the proximal surfaces of molars and premolars, adjacent to the site where the elastomeric separators were inserted; and refusal to participate in the study.

Methods

Grouping

Patients were randomly distributed into the following groups: group 1 (control), this group did not receive any LED application for pain control and group 2 (experimental), this group had LED application for pain control. None of the groups know the existence of the other, avoiding in this way some sort of bias. Participants in both groups were asked to make use of painkillers (Paracetamol, Tylenol®, Sanofi-Aventis Ltda. Pharmaceuticals, Suzano-SP, Brazil, 1 g every 6 h until the pain decrease) in case of pain. In this case, they were excluded from the study.

Clinical procedures for insertion of the separating elastics

After defining group distribution, the separating elastics were inserted with the aid of two dental floss segments, on the distal and mesial surfaces of the upper right first molar, according to literature recommendations [15, 18, 24]. The patients should verify if the separators remained in place, especially when performing oral hygiene. Then, they were asked to fill out a form that was designed to assess pain sensitivity after insertion of separators. Thus, patients received four cards with a visual analog scale (VAS) to determine the pain index, followed by phototherapy with LED.

Irradiation protocol

In the experimental group, LED phototherapy was performed with Fisioled® (MMOptics, São Carlos, São Paulo, Brazil, λ846 ± 20 nm, 180 mW, 22 s, 4 J, 8 J/cm2, 0.36 W/cm2, spot of 0.5 cm2, spot diameter 0.8 cm) (Table 1). The light was applied in two points: one on the buccal aspect and distally (between the cervical and root thirds) and one point on the palatal surface, mesial (between the cervical and root thirds) (Fig. 1). The total energy density was 16 J/cm2 per session.

Pain scoring

The patients were instructed to place a mark next to the score corresponding to the amount of pain they felt. After insertion of the elastic separators, the patient scored the VAS, and LED was then applied (T1). The patient returned within 48 and 72 h counted from the day of installation (T2 and T3, respectively) to rescore the pain scale. LED protocol was performed, as determined by Pinheiro et al. [15]. The elastic separators were removed on the seventh day after installation, when the patient scored the last VAS (T4) indicating the pain they felt on the period. At this time, the LED was no longer applied. The control group was also given the same guidelines and performed the same procedures as the experimental group, but with no LED application.

Statistical analysis

Group sample sizes of 20 and 20 achieve 91,123% power to reject the null hypothesis of equal means when the population mean difference was 2 with standard deviations of 1.9 for group 1 and 1.8 for group 2, and with a significance level (alpha) of 0.05 using a two-sided two-sample unequal-variance t test.

Statistical analysis was performed using the R Core Team 3.1.2 (R, a language and environment for statistical computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Initially, to compare a descriptive analysis of the results (median and quartiles) and the level of pain at various times in each group, Friedman’s nonparametric test was used followed by a posteriori test of Dunn. To compare the level of pain between the LED and control groups, the Student t test or Mann-Whitney tests were used upon data distribution. The significance level adopted for this study was 5%.

Results

The total sample consisted of 30 females and 10 males. The levels of pain did not vary between men and women during the experimental time (p > 0.05).

Figure 2 shows the level of pain at each time in LED and control groups as well as a comparison between the two groups. Increased pain was observed from installation time and up to 48 h thereafter. Furthermore, the pain decreased after 72 h and reaching the lowest level after 7 days. Comparison of pain levels through time among the groups showed that the pain reduction was statistically significant in all times, except on the insertion moment where no difference was perceptive.

Discussion

Pain in dentistry, specifically in orthodontics, is a constant concern of professionals as it directly affects daily clinical practice. Increasingly, the use of drugs should be avoided because of their side effects, and the use of non-pharmacological methods that provide the same efficacy are increasing [2, 6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17, 19,20,21,22,23,24,25, 28]. In the present study, three patients in the control group used painkillers to stop the pain. Although they were excluded from the study to avoid bias, it is important to emphasize this fact, as it shows that LED should help reduce the perception of pain since it does not cause any side effects. In the study by Pinheiro and Bittencourt [15], which also evaluated pain levels in the tooth separating process, but using laser light, two patients reported using some type of medication [15].

However, there are few experimental studies aimed testing these non-pharmacological methods, demonstrating the necessity of further research in this area with the purpose of developing new protocols in pain management of pain reported by patients [2].

The VAS was used to measure the level of pain, according to previous studies that assess pain sensitivity. Moreover, it is considered a reliable, easy to understand tool [9, 24, 29,30,31]. From 0 to 2, pain is assessed as mild; 3–7, moderate; and 8–10, intense.

This study did not consider dental rotations, positioning of neighboring teeth, and proximity of the roots, as in other studies in the literature [15].

The primary effect of the LED is the stimulus to the production of substances related to the processes of pain and inflammation, stimulating the production of intracellular adenosine triphosphate (ATP), favoring cell division and ionic transport, modulating vasodilation, and generating increased vascular permeability. This therapy has been widely used as an adjuvant, alternative, and non-invasive treatment, promoting the acceleration of the healing process, pain reduction, and edema as well as on modulating inflammation [18].

Some factors such as wavelength, energy, energy density, power, and irradiation stage influence the modulation of phototherapy responses [32,33,34,35,36]. Phototherapy-related studies in orthodontics have shown the importance of employing low doses to ensure treatment effectiveness since any energy densities higher than 20 J/cm2 has so far shown opposite reactions [24, 37, 38]. This study used an energy density of 8 J/cm2 per point and it was applied at two points. The total energy density was 16 J/cm2, with a power of 150 mW, which is within the parameters recommended in the literature.

Analgesia provided by electromagnetic radiation is a new treatment modality that features the advantage of being easy to apply, non-invasive, and affordable. Besides, it does not cause any unknown adverse tissue reactions [6, 17, 24]. Tortamano et al. [17] emphasized the fact that the only reason to avoid using it clinically is the time required to apply it. Nevertheless, in this study, which employed the parameters described above, the exposure time (22 s) can be considered low.

There are several studies that employed laser light (coherent light) in orthodontics [5, 6, 11, 14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22, 24,25,26,27, 31,32,33, 36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45]. However, very few studies have been conducted with non-coherent light, and these studies were largely conducted in experimental animals [37, 40]. Although previous studies did achieve promising results, only one study was identified as a clinical trial involving LED therapy in orthodontics [24]. This fact once again underscores the relevance of this study.

In this study, LED proved to be effective in pain reduction, because when compared to the control group, led reduces the pain with statistically significant difference (p < 0.05); except for T1 (at elastic installation), where no difference was found between groups (p = 0.659) (Table 2). Considering that the LED effects are not immediate, this may explain why no difference in the level of pain was found between groups as scoring occurred immediately after the insertion of the separators. One may question why the choice of 48 h for the initial assessment of the pain [19, 21]. This was chosen because the peak of pain occurs up to 36 h after the insertion of the separators and difficulty to have the patients back to the service 24 h after the procedure due to economic constraints for most of them.

This result corroborates a previous study [24], which compared the effects of LED and laser in reducing pain during the tooth separating process, and found that both were effective, although the results achieved with the use of LED were considered better than with the use of laser.

The first 36 h after elastic separators insertion is critical on regards of pain. Clinically, the discomfort caused by the insertion of elastic separators is minimal after 1 week [19, 23, 28]; however, up to this time, the pain is intense [15, 42,43,44]. Our results showed that, the comparison of the pain levels through time between the groups, the pain reduction observed on LED-irradiated subjects was statistically significantly (p < 0.001) lower at all time points (48, 72, and 96 h), except at the insertion moment, where no difference between groups was observed. Because of the great reduction of pain experienced by the patient, no drugs such as analgesics and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS) are necessary for pain control. This fact demonstrates the effectiveness of the use of LED phototherapy on orthodontic treatment, offering both more comfort and lower costs for patients. In this study, higher peak of pain occurred 48 h after the elastic separator insertion [19] unlike statistically significant difference other studies where the higher peak of pain occurred within 24 h [15, 17]. It is believed that this variation is normal since peak pain occurs within the first 3 days after force application [15, 42,43,44].

Despite gender variable known to influence pain [15], in the present study, 75% of patients were female and 25% male; this seemed not to be relevant as no statistically significant difference between genders (p > 0.05) was observed. In agreement with this finding, several authors [42,43,44,45,46,47] reported no correlation between gender and discomfort during orthodontic treatment.

The scientific literature is controversial regarding the influence of age on pain perception. Some claim that teenagers are the most prone given the development phase they are experiencing; others believe that children are more susceptible [47]. There are also those who argue that adults are more prone to experiencing higher pain perceptions, or that there is no significant difference between the intensity of discomfort and age [43]. In this study, the population age ranged from 20 to 30 years. In the LED group, the mean age was 24.3 years and in the control group, 23.4 years.

Finally, pain relief and quicker treatment time are important demands for both orthodontists and patients. The increased number of publications, including clinical trials, systematic reviews, and meta-analysis, provided a large number of clinical protocols in order to achieve these goals. For this, a variety of light sources have been investigated, including the use NIR (λ600–1000 nm) lasers or LED light. The photobiomodulation on pain relief is related to the neuronal effect of phototherapies including stabilization of membrane potential and inhibiting activation of the pain signal. Moreover, the decrease on the levels of inflammatory mediators, such as prostaglandin E2, known to cause painful sensations in the inflammatory response, is observed when using light therapies [4, 14, 17, 19, 21, 22, 25, 28, 30, 32, 38, 41,42,43,44,45,46,47].

Conclusions

The results of the present investigation are indicative that IR-LED phototherapy is effective on pain reduction reported by the patients during the tooth separation process, reducing with the statistically significant difference pain levels.

References

Carroll JD (2014) Tooth movement in orthodontic treatment systematic review omitted significant articles. Photomed Laser Surg 32:310–311

Krishnan V (2007) Orthodontic pain: from causes to management- a review. Eur J Orthod 29:170–179

Burstone CJ, Choy K (2017) Fundamentos Biomecânicos da Clínica Ortodôntica. Quintessence, São Paulo

Almeida VL, Gois VLA, Andrade RNM, Cesar CPHAR, Albuquerque-Junior RLC et al (2016) Efficiency of low-level laser therapy within induced dental movement: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Photochem Photobiol B Biol 158:258–266

Higashi DT, Andrello AC, Tondelli PM, Filho DOT, Ramos SP (2017) Three consecutive days of application of LED therapy is necessary to inhibit experimentally induced root resorption in rats: a microtomographic study. Lasers Med Sci 32(1):181–187

Lim HM, Lew KK, Tay DK (1995) A clinical investigation of the low-level laser therapy in reducing orthodontic post adjustment pain. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop 108:614–622

Carroll JD, Milward MR, Cooper PR, Hadis M, Palin WM (2014) Developments in low level light therapy (LLLT) for dentistry. Dent Mater 30:465–475

Law SLS, Southard KA, Law AS, Logan HL, Jakobsen J (2000) An evaluation of preoperative ibuprofen for treatment of pain associated with orthodontic separator placement. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop 118:629–635

Bernhardt MK, Southard KA, Batterson KD, Logan HL, Baker KA, Jakobsen JR (2001) The effect of preoperative and/or postoperative ibuprofen therapy for orthodontic pain. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop 120:20–27

Polat O, Karaman AL (2005) Pain control during fixed orthodontic appliance therapy. Angle Orthod 75:210–215

Turhani D, Scheriau M, Kapral D, Benesch T, Jonke E, Bantleon HP (2006) Pain relief by single low-level laser irradiation in orthodontic patients undergoing fixed appliance therapy. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop 130:371–377

Bird SE, Williams K, Kula K (2007) Preoperative acetaminophen vs ibuprofen for control of pain after orthodontic separator placement. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop 132:504–510

Bergius M, Brogerg AG, Hakeberg M, Berggren U (2008) Prediction of prolonged pain experiences during orthodontic treatment. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop 133(3):339.e1-8

Ren C, McGrath C, Yang Y (2015) The effectiveness of low-level diode laser therapy on orthodontic pain management: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lasers Med Sci 30:1881–1893

Pinheiro ALB, Bittencourt MAV, Filho RFAF (2008) Avaliação clínica da ação antiálgica do laser de baixa potência após instalação de separadores ortodônticos. Rev Assoc Paul Cir Dent 62:98–104

Youssef M, Ashkar S, Hamade E, Gutknecht N, Lampert F, Mir M (2008) The effect of low-level laser therapy during orthodontic movement: a preliminary study. Lasers Med Sci 23:27–33

Tortamano A, Lenzi DC, Haddad AC, Bottino MC, Dominguez GC, Vigorito JW (2009) Low-level laser for pain caused by placement of the first orthodontic arch wire. A randomized clinical trial. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Ortho 136:662–667

Stein S, Korbmacher-Steiner H, Popovic N, Braun A (2015) Pain reduced by low-level laser therapy during use of orthodontic separators in early mixed dentition. J Orofac Orthop 76:431–439

Borzabadi-Farahani A, Cronshaw M (2017) Lasers in orthodontics. In: Coluzzi D, Parker S (eds) Lasers in dentistry—current concepts. Textbooks in Contemporary Dentistry. Springer, Cham

Furquim RD, Pascotto RC, Neto JR, Cardoso JR, Ramos AL (2015) Low-level laser therapy effects on pain perception related to the use of orthodontic elastomeric separators. Dental Press J Orthod 20(3):37–42

Bjordal JM, Johnson MI, Iversen V, Aimbire F, Lopes-Martins RA (2006) Low-level laser therapy in acute pain: a systematic review of possible mechanisms of action and clinical effects in randomized placebo-controlled trials. Photomed Laser Surg 24(2):158–168

Mizutani K, Musya Y, Wakae K, Kobayashi T, Tobe M, Taira K, Harada T (2004) A clinical study on serum prostaglandin E2 with low-level laser therapy. Photomed Laser Surg 22(6):537–539

Polat O (2007) Pain and discomfort after orthodontic appointments. Semin Orthod 13(4):292–300

Esper MALR, Nicolau RA, Arisawa EALS (2011) The effect of two phototherapy protocols on pain control in orthodontic procedure—a preliminary clinical study. Lasers Med Sci 26:657–663

Sant’Anna EF, Araújo MTS, Nojima LI, Cunha AC, Silveira BL, Marquezan M (2017) High-intensity laser application in orthodontics. Dental Press J Orthod 22(6):99–109

Habib FAL, Gama SKC, Ramalho LMP et al (2010) Laser-induced alveolar bone changes during orthodontic movement: a histological study on rodents. Photomed Laser Surg 28:823–830

AlSayed HMMA, Sultan K, Hamadah O (2016) Low-level laser therapy effectiveness in accelerating orthodontic tooth movement: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Angle Orthod 87(4):499–504

Bondemark L, Fredriksson K, Ilros S (2004) Separation effect and perception of pain and discomfort from two types of orthodontic separators. World J Orthod 5:172–176

Gallagher EJ, Liebman M, Bijur PE (2001) Prospective validation of clinically important changes in pain severity measured on a visual analog scale. Ann Emerg Med 38:633–638

Topolski F, Moro A, Correr GM, Schimim SC (2018) Optimal management of orthodontic pain. J Pain Res 11:589–598

Lobato PC, Garcia VJ, Kasem K, Torrent JMU, Walton VT, Céspedes CM (2014) Tooth movement in orthodontic treatment with low-level laser therapy: a systematic review of human and animal studies. Photomed Laser Surg 32:302–309

Sousa MVS, Pinzan A, Consolaro A, Henriques JFC, Freitas MR (2014) Systematic literature review: influence of low-level laser on orthodontic movement and pain control in humans. Photomed Laser Surg 32:592–599

Barbosa KGN, Sampaio TPD, Rebouças PRM, Catão MHCV, Gomes DQC, Pereira JV (2013) Analgesia during orthodontic treatment with low intensity laser: systematic review. Rev Dor 14(2):137–141

Brugnera A Jr (2009) Laser phototherapy in dentistry. Photomed Laser Surg 27:533–534

Enwemeka CS (2009) Intricacies of dose in laser phototherapy for tissue repair and pain relief. Photomed Laser Surg 27:387–393

Qamruddin I, Alam MK, Fida M, Khan AG (2016) Effect of a single dose of low-level laser therapy on spontaneous and chewing pain caused by elastomeric separators. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthoped 149(1):62–66

Seifi M, Shafeei HA, Daneshdoost S, Mir M (2007) Effects of two types of low-level laser wavelengths (850 and 690nm) on the orthodontic tooth movements in rabbits. Lasers Med Sci 22:261–264

Fujita S, Yamaguchi M, Utsunomiya T, Yamamoto H, Kasai K (2008) Low-energy laser stimulates tooth movement velocity via expression of RANK and RANKL. Orthod Craniofacial Res 11:143–155

Almallha MME, Almahdi WH, Hajeer MY (2016) Evaluation of low level laser therapy on pain perception following orthodontic elastomeric separation: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Diagn Res 10:23–28

Goulart CS, Nouer PR, Mouramartins L, Garbin IU, de Fátima ZLR (2006) Photoradiation and orthodontic movement: experimental study with canines. Photomed Laser Surg 24:192–196

Shi Q, Yang S, Jia F, Xu J (2015) Does low-level laser therapy relieves the pain caused by the placement of the orthodontic separators? A meta-analysis. Head Face Med 11:28

Farias RD, Closs LQ, Jr SAQM (2016) Evaluation of the use of low-level laser therapy in pain control in orthodontic patients: a randomized split-mouth clinical trial. Angle Orthod 86(2):193–198

Eslamian L, Farahani AB, Azhiri AH, Badiee MR, Fekrazad R (2014) The effect of 810nm low-level laser therapy on pain caused by orthodontic elastomeric separators. Lasers Med Sci 29:559–564

Marini I, Bartolucci ML, Bartolotti F, Innoceti G, Gatto MR, Bonetti GA (2013) The effect of diode superpulsed low-level laser therapy on experimental orthodontic pain caused by elastomeric separator: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Lasers Med Sci 30:35–41

Nóbrega C, Silva EMK, Macedo CR (2013) Low-level laser therapy for treatment of pain associated with orthodontic elastomeric separator placement: a placebo-controlled randomized double blind clinical-trial. Photomed Laser Surg 31(1):10–17

Erdinç AME, Dinçer B (2004) Perception of pain during orthodontic treatment with fixed appliances. Eur J Orthod 26:79–85

Kim WT, Bayome M, Park JB, Park JH, Baek SH, Kook YA (2013) Effect of frequent laser irradiation on orthodontic pain. A single-blind randomized clinical trial. Angle Orthod 83(4):611–616

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

This case-control, quantitative and qualitative, longitudinal study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the School of Dentistry of the Federal University of Bahia (Proc. 34159014.30000.5024).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical statement

The authors hereby confirm that this work followed the Brazilian Resolution CNS 196/96 and was approved by the institution’s Ethics Committee (Proc 34159014.3.0000.524).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Figueira, I.Z., Sousa, A.P.C., Machado, A.W. et al. Clinical study on the efficacy of LED phototherapy for pain control in an orthodontic procedure. Lasers Med Sci 34, 479–485 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10103-018-2617-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10103-018-2617-3