Abstract

Difficult to diagnose and early non-melanoma skin cancer lesions are frequently seen in daily clinical practice. Besides precancerous lesions such as actinic keratosis, basal cell carcinomas (BCCs) score the highest frequency in skin tumors. While infiltrative and nodular BCCs require a surgical treatment with a significant impact on the patients’ quality of life, early and superficial BCCs might benefit from numerous conservative treatments, such as topical immune-modulators or photodynamic therapy. Dermoscopy has shown a high sensitivity and specificity in the diagnosis of early BCCs, and non-invasive imaging techniques like reflectance confocal microscopy (RCM) have proven to be helpful. The aim of our study was to investigate the importance of RCM in the diagnosis of BCCs with indistinct clinical and dermoscopic features. We retrospectively examined 27 histologically proven BCCs in which diagnosis was not possible based on naked eye examination; we separately reviewed clinical, dermoscopic, and confocal microscopy features and evaluated the lesions meeting the common diagnostic criteria for BCCs, and our diagnostic confidence. All lesions were clinically unclear, with no characteristic features suggestive for BCC; dermoscopy showed in most cases unspecific teleangiectasias (74 %) and micro-erosions (52 %). Confocal microscopy revealed in most of the cases the presence of specific criteria: peripheral palisading of the nuclei (89 %), clefting (70 %), stromal reaction (70 %), dark silhouettes (70 %), inflammatory particles (70 %), and tumor islands (67 %). In the absence of significant diagnostic clinical signs and with unclear dermoscopic features, specific confocal patterns were present in most of the lesions and enabled a correct diagnosis. In the absence of significant clinical features of BCC and in the case of uncertain dermoscopy, striking confocal features are detectable and easy to recognize in most cases. Confocal microscopy can therefore be instrumentful in the diagnosis of the so-called invisible BCCs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common skin tumor nowadays, with approximately 2.8 million new cases a year in the USA, with tendential increasing [1]. In Europe, a recent Dutch study confirmed the growing tendency with a lifetime BCC risk of 1 in 5 (21 %) men and 1 in 6 (18 %) women [2]. Different histological subtypes of BCC have been described: nodular, morpheaform, infiltrative, superficial, ulcerated, baso-squamous carcinoma, and combinations of these subtypes. In advanced cases, removal approach is the first choice, with Mohs micrographic surgery as the gold standard [3]. However, for early and superficial BCCs, topical imiquimod or photodynamic therapy offer good therapeutic alternatives [4].

An early and correct identification of BCCs enables correct treatment and avoids unnecessary excisions; in case of diagnostic uncertainty, however, a pre- and sometimes even post-treatment biopsy is necessary in order to ensure the correct diagnosis.

The role of dermoscopy in the diagnosis of BCCs and prediction of their histological subtype has been widely demonstrated in the literature. Beginning with Menzies’ model, the combination of easily recognizable diagnostic features (absence of pigment network, leaf-like structures, spoke-wheel areas, large blue-gray ovoid nests, blue-gray globules, arborizing teleangiectasias, and ulceration) allowed a sensitivity of 93 % and a specificity of 89 % in the differential diagnosis with melanoma [5]. Various other studies reported promising results, which analyzed the features of pigmented and superficial basal cell carcinomas [5–12].

In the daily clinical routine, however, some cases raise the suspicion of BCC but remain unclear, with non-yelding dermoscopy. Especially in facial lesions of uncertain nature, the effective treatment might be delayed until progression to more invasive stages. Non-invasive tools, such as reflectance confocal microscopy (RCM) have the potential of ensuring earlier diagnosis and treatment.

Not only dermoscopy, but also RCM has shown its utility in the non-invasive diagnosis of BCC. In particular, RCM showed diagnostic sensitivity of 97 % and specificity of 93 % [13–17] and provided good correlations with the histological subtypes [18, 19].

The aim of our study was to establish the role of RCM in the diagnosis of BCCs in cases of difficult to diagnose facial BCCs, with indistinct clinical and dermoscopical features.

Materials and methods

We retrospectively examined 31 BCCs that had been screened in the Dermoscopy and Imaging outpatient clinic of the Department of Dermatology and Allergology of the Ludwig-Maximilian University of Munich between January 2014 and September 2015. We then selected 27 histologically proven BCCs which shared the absence of striking clinical features based on naked eye examination; we separately reviewed in a blinded manner the clinical, dermoscopic, and confocal microscopy features and evaluated the lesions meeting the common diagnostic criteria for BCCs.

Only lesions with complete macroscopic, dermatoscopic, and confocal documentation; histological diagnosis; and follow-up were included in the study. The selected patients were 12 males and 15 females with a mean age of 67 years. The tumors were located on the nose (63 %), on the cheeks 15 % while the remaining ones arose on other facial sites. Eleven (41 %) BCCs developed within a scar.

The dermoscopic images were captured with Fotofinder (FotoFinderSystems GmbH, Germany), at ×10 field magnification. RCM images were acquired using Vivascope 1500 (Mavig, Germany), a non-invasive diagnostic tool based on an 830-nm diode laser and a ×30 objective lens with a numerical aperture of 0.9. Its maximum laser power is 40 mW, which causes no tissue damage nor pain. Its penetration depth is up to 250–300 μm, its axial resolution 3–5 μm and its lateral resolution 1 μm. Three different layers corresponding to the epidermis, dermo-epidermal junction, and superficial dermis were examined for each lesion.

Clinical features were nodular structure, pearl-shiny borders, pigmentation, ulceration, raised borders, scaling, crusting, teleangiectasias, pink color, and fibrous-scarring appearance.

Dermoscopic features were selected according to the literature: arborizing vessels, leaf-like structures, blue-gray ovoid nests, multiple blue-gray dots, spoke-wheel structures, concentric structures, fine telangiectasias, micro-ulceration/multiple small erosions, shiny white to red structureless areas, and yellow stripes [7, 10, 12, 19]. Confocal parameters were defined based on already published data: ulceration, streaming of the epidermis, tumor islands, cord-like structures, dark silhouettes, peripheral palisading, peripheral clefting, onion-like structures, stromal reaction, presence of inflammatory (bright) particles and cells, dendritic cells, and increased vascularization (dilated vessels) [5, 15, 18–23].

Since the examination had no implications in the diagnostic process nor in the choice of therapeutic strategies, the approval of the ethics committee was not required.

Results

Of the examined tumors, the majority was of the nodular histological subtype (10); other histological subtypes were: superficial (7), morpheaform (7), infiltrative (1), and ulcerated (2). The mixed types were classified based on the most prevalent component.

All lesions were clinically unclear, with pink color (15) and fibrous-scarring appearance (10) as the most common features; other characteristics were nodular structure (7), pigmentation (2), ulceration (2), and scaling (1). In most cases, telangiectasias were present but not distinguishable from the background ones. The typical raised pearly-shine borders were not visible in any of the lesions. Dermoscopy was non-diagnostic and showed in most cases: unspecific teleangiectasias (20), arborizing vessels (11), and micro-erosions (14); other features were: blue-gray dots (6), blue-gray ovoid nests (1), and shiny white to red structureless areas (10); the typical leaf-like structures, spoke-wheel areas, concentric structures, and yellow stripes could not be detected.

In contrast, confocal microscopy revealed the presence of typical basal cell carcinoma criteria: peripheral palisading of the nuclei (24), streaming of the epidermis (22), dark silhouettes (19), stromal reaction (19), clefting (19), inflammatory particles (19), tumor islands (18), cord-like structures (9), ulceration (8), dendritic structures (7), and canalicular vessels (17).

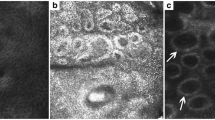

The most common clinical features were pink color (55 %) and fibrous-scarring appearance (37 %). In videodermoscopy, the BCCs examined showed teleangiectasias (74 %), micro-ulcerations (52 %), and arborizing vessels (41 %). Confocal microscopy revealed peripheral palisading in 89 % of the cases, streaming of the epidermis (81 %), dark silhouettes (70 %), tumor islands (67 %), and stromal reaction, clefting, and inflammatory particles (70 %) (Table 1) (Figs. 1 and 2).

From left to right: clinical, dermoscopical, confocal, and histological detail of our lesions. a 73-year-old male with nodular BCC, note well-circumscribed tumor islands with clefting and palisading. b 75-year-old female with superficial BCC. c 36-year-old female with nodular BCC and infiltrative growth pattern, note tumor islands surrounded by inflammatory infiltrate. d 73-year-old male with recurrence of superficial BCC within a scar

From left to right: clinical, dermoscopical, confocal, and histological detail of lesions. a 78-year-old male with superficial BCC. Note dark silhouettes surrounded by collagen in RCM. b 67-year-old male with nodular BCC. Note the tumor island in RCM corresponding to the basaloid island surrounded by stromal reaction in histology. c 75-year-old female with recurrence of superficial BCC on her nose. Note typical cord-like structures in RCM. d 49-year-old female with recurrence of nodular basal cell carcinoma on her nose

Discussion

The clinical eye has been the only tool in the diagnosis of skin cancer for many years. There are few reports on the efficacy of naked eye examination in the diagnosis of BCC, which confirm, however, that the clinician’s ability to make a proper diagnosis is strictly dependent on his clinical experience and tumor stage. The positive predictive value for clinically diagnosing BCC ranged from 43 to 80 % when using main clinical criteria such as pearly borders, teleangiectasias, and pigmentation; in most cases, however, the patients were preselected among those referred to the study centers with suspicion of BCC [24–28]. In the absence of these clinical criteria, however, the diagnostic confidence was very low.

Since the beginning of the dermoscopy era in the 1980s, huge progress has been made in the early diagnosis of skin cancer, and diagnostic accuracy has reached a significative improvement, both in melanoma and non-melanoma skin cancer [29–33]. The role of dermoscopy in the early diagnosis of BCCs and prediction of their histological subtype has been validated in numerous studies. Sensitivity and specificity of dermoscopy in differentiating BCCs from other skin tumors are quite high, ranging from 95–87 to 96–97 %, respectively [5, 10, 34]. Furthermore, distinct dermoscopic criteria for superficial and other subtypes of BCC have been described, identifying leaf-like structures and short fine superficial telangiectasias in the absence of arborizing vessels, large blue-gray ovoid nests, or ulceration as predictors of superficial BCC with a sensitivity of 81.9 % and a specificity of 81.8 %. Ovoid nests, arborizing vessels, and large ulcerations were found in nodular and infiltrative BCCs; the latter were identified by shiny white-red structureless areas and small arborizing vessels with reduced branching tendency [7, 9, 34, 35].

The literature has, however, has shown significant variability in the prevalence of each specific dermoscopic feature for the diagnosis of BCC, with remarkable differences among studies, 28–81 % for arborizing vessels, 20–84 % for blue-gray ovoid nests, and 27–42 % for ulceration [5–12]. Moreover, while the diagnostic accuracy of pigmented BCCs has been widely tested, the findings concerning the diagnosis of non-pigmented BCCs are less specific, although arborizing vessels and micro-ulcerations are considered the most predictive features [10, 36].

In the daily clinical practice, however, the analysis of clinical and dermoscopic criteria might not be sufficient to ensure the diagnosis of BCC in lesions where the abovementioned parameters are lacking. In high-risk patients, when recurrence is suspected or when a lesion is enlarging, a skin biopsy should be taken, with the risk of overtreatment or low compliance.

In those cases, a significant help in improving the diagnostic accuracy of both clinical examination and dermoscopy is provided by RCM. The device, an infrared light microscope based on a diode laser of 830 nm, allows the visualization of skin structures with a cellular resolution and thus performing a kind of in vivo biopsy [37]. The use of in vivo RCM has been widely tested in the diagnosis and monitoring of many skin pathologies, including treatment monitoring of BCC under oral hedgehog inhibitors [38], with a large number of studies examining melanoma and non-melanoma skin cancer. In the last years, an ex vivo confocal device has been developed and shown excellent correlations with histology and utility in the therapeutic management of basal cell carcinomas [39–41].

The diagnostic criteria for the confocal diagnosis of BCC have been firstly described by Gonzales et al., and their diagnostic accuracy has been subsequently validated by numerous studies [13–16, 20, 42–44]. In particular, Nori and colleagues [20] reported a specificity of 95.7 % and a sensitivity of 82.9 % using a set of five criteria (presence of elongated monomorphic basaloid nuclei, polarization of these nuclei along the same axis of orientation, prominent inflammatory infiltrate, increased vasculature, and pleomorphism of the overlying epidermis indicative of actinic damage) applied to 152 skin lesions, while Guitera and colleagues [43] obtained 100 % sensitivity and 88.5 % specificity on a case series of 710 lesions which also included malignant melanoma. The group developed a diagnostic algorithm for the differential diagnosis of the two skin tumors, with polarization of the cells in the epidermis, telangiectasias, convoluted vessels, basaloid islands, dark silhouettes, and clefting as the positive features for the diagnosis of BCC. In 2011, Ulrich and colleagues described the presence of peritumoral clefting as an additional criterion that correlates in vivo with the peritumoral deposition of mucin [44].

As for dermoscopy, specific RCM criteria related to the histological subtype have been described. An accurate prediction of the histological subtype is useful in clinical practice, since it helps in therapeutic planning. Longo and colleagues identified cord-like structures, together with clefting and peripheral palisading as the most common features in superficial BCCs, with dark silhouettes outlined by bright coarse collagen fibers often present in non-pigmented superficial BCCs and infiltrative BCCs. Nodular BCCs show bright tumor islands, peripheral palisading, clefting, and enlarged blood vessels with sometimes ulceration [19].

In our study, at least four confocal criteria for the diagnosis of BCC were found in every lesion, ensuring a diagnostic confidence able to guide the patient in the subsequent management. Confocal microscopy enabled the in vivo diagnosis although the typical clinical BCC parameters were absent, and the dermatoscopic features not specific enough to demonstrate or exclude malignancy. In particular, RCM showed high diagnostic accuracy in case of lesions arising on pre-existing scars with suspicion of recurrence, with non-informative clinical and dermatoscopic features. The RCM features in these clinically indistinctive BCCs were also those described in the literature as the most specific for the diagnosis of BCC and part of the diagnostic algorithms, so that the use of RCM had an instant impact on the further management of the lesions. Additionally, in some cases, although dermoscopical examination suggested superficial BCCs of the case series would have been classified as of the superficial types, which would lead to inappropriate treatment such as topical or photodynamic therapy, RCM parameters showed features of nodular and infiltrative types and guided the clinical decision-making to surgical excision. In our hands, RCM achieved a high-enough diagnostic confidence to directly address the patient to Mohs surgery, without the necessity of performing a skin biopsy. Thus, the method is rapid, cost effective, and non-invasive for the patient.

In conclusion, in facial papues with unclear clinical features and non-diagnostic dermoscopy, confocal microscopy aids in the correct diagnosis and helps to avoid unnecessary biopsy and follow-up of the so-called invisible BCCs.

References

What are the key statistics about basal and squamous cell skin cancers? American Cancer Society. Available at http://www.cancer.org/cancer/skincancer-basalandsquamouscell/detailedguide/skin-cancer-basal-and-squamous-cell-key-statistics. April 30, 2015; Accessed 30 Sept 2015.

Flohil SC, Seubring I, van Rossum MM et al (2013) Trends in basal cell carcinoma incidence rates: a 37-year Dutch observational study. J Invest Dermatol 133:913–918

Kauvar AN, Cronin T Jr, Roenigk R, Hruza G, Bennett R (2015) Consensus for nonmelanoma skin cancer treatment: basal cell carcinoma, including a cost analysis of treatment methods. Dermatol Surg 41:550–571

Trakatelli M, Morton C, Nagore E et al (2014) Update of the European guidelines for basal cell carcinoma management. Eur J Dermatol 24:312–329

Menzies SW, Westerhoff K, Rabinovitz H et al (2000) Surface microscopy of pigmented basal cell carcinoma. Arch Dermatol 136:1012–1016

Pehamberger H, Steiner A, Wolff K (1987) In vivo epiluminescence microscopy of pigmented skin lesions. I. Pattern analysis of pigmented skin lesions. J Am Acad Dermatol 17:571–583

Giacomel J, Zalaudek I (2005) Dermoscopy of superficial basal cell carcinoma. Dermatol Surg 31:1710–1713

Demirtasoglu M, Ilknur T, Lebe B et al (2006) Evaluation of dermoscopic and histopathologic features and their correlations in pigmented basal cell carcinomas. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 20:916–920

Scalvenzi M, Lembo S, Francia MG, Balato A (2008) Dermoscopic patterns of superficial basal cell carcinoma. Int J Dermatol 47:1015–1018

Altamura D, Menzies SW, Argenziano G et al (2010) Dermatoscopy of basal cell carcinoma: morphologic variability of global and local features and accuracy of diagnosis. J Am Acad Dermatol 62:67–75

Micantonio T, Gulia A, Altobelli E et al (2011) Vascular patterns in basal cell carcinoma. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 25:358–361

Liebman TN, Jaimes-Lopez N, Balagula Y et al (2012) Dermoscopic features of basal cell carcinomas: differences in appearance under non-polarized and polarized light. Dermatol Surg 38:392–399

Gonzalez S, Tannous Z (2002) Real-time, in vivo confocal reflectance microscopy of basal cell carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol 47:869–874

Segura S, Puig S, Carrera C, Palou J, Malvehy J (2007) Dendritic cells in pigmented basal cell carcinoma: a relevant finding by reflectance-mode confocal microscopy. Arch Dermatol 143:883–886

Scope A, Mecca PS, Marghoob AA (2009) skINsight lessons in reflectance confocal microscopy: rapid diagnosis of pigmented basal cell carcinoma. Arch Dermatol 145:106–107

Castro RP, Stephens A, Fraga-Braghiroli NA et al (2015) Accuracy of in vivo confocal microscopy for diagnosis of basal cell carcinoma: a comparative study between handheld and wide-probe confocal imaging. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 29(6):1164–1169

Kadouch DJ, Schram ME, Leeflang MM et al (2015) In vivo confocal microscopy of basal cell carcinoma: a systematic review of diagnostic accuracy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 29:1890–1897

Peppelman M, Wolberink EA, Blokx WA et al (2013) In vivo diagnosis of basal cell carcinoma subtype by reflectance confocal microscopy. Dermatology 227:255–262

Longo C, Lallas A, Kyrgidis A et al (2014) Classifying distinct basal cell carcinoma subtype by means of dermatoscopy and reflectance confocal microscopy. J Am Acad Dermatol 71:716–724, e1

Nori S, Rius-Diaz F, Cuevas J et al (2004) Sensitivity and specificity of reflectance-mode confocal microscopy for in vivo diagnosis of basal cell carcinoma: a multicenter study. J Am Acad Dermatol 51:923–930

Ahlgrimm-Siess V, Cao T, Oliviero M et al (2010) The vasculature of nonmelanocytic skin tumors in reflectance confocal microscopy: vascular features of basal cell carcinoma. Arch Dermatol 146:353–354

Longo C, Farnetani F, Ciardo S et al (2013) Is confocal microscopy a valuable tool in diagnosing nodular lesions? A study of 140 cases. Br J Dermatol 169:58–67

Longo C, Moscarella E, Argenziano G et al (2015) Reflectance confocal microscopy in the diagnosis of solitary pink skin tumours: review of diagnostic clues. Br J Dermatol 173:31–41

Schwartzberg JB, Elgart GW, Romanelli P et al (2005) Accuracy and predictors of basal cell carcinoma diagnosis. Dermatol Surg 31:534–537

Farroha A, Dziewulski P, Shelley OP (2013) Estimating the positive predictive value and sensitivity of the clinical diagnosis of basal cell carcinoma. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 66:1013–1015

Heal CF, Raasch BA, Buettner PG, Weedon D (2008) Accuracy of clinical diagnosis of skin lesions. Br J Dermatol 159:661–668

Green A, Leslie D, Weedon D (1988) Diagnosis of skin cancer in the general population: clinical accuracy in the Nambour survey. Med J Aust 148:447–450

Bolognia JL, Berwick M, Fine JA (1990) Complete follow-up and evaluation of a skin cancer screening in Connecticut. J Am Acad Dermatol 23:1098–1106

Argenziano G, Giacomel J, Zalaudek I et al (2013) A clinico-dermoscopic approach for skin cancer screening: recommendations involving a survey of the International Dermoscopy Society. Dermatol Clin 31:525–534, vii

Argenziano G, Cerroni L, Zalaudek I et al (2012) Accuracy in melanoma detection: a 10-year multicenter survey. J Am Acad Dermatol 67:54–59

Blum A, Rassner G, Garbe C (2003) Modified ABC-point list of dermoscopy: a simplified and highly accurate dermoscopic algorithm for the diagnosis of cutaneous melanocytic lesions. J Am Acad Dermatol 48:672–678

Rosendahl C, Tschandl P, Cameron A, Kittler H (2011) Diagnostic accuracy of dermatoscopy for melanocytic and nonmelanocytic pigmented lesions. J Am Acad Dermatol 64:1068–1073

Kittler H, Pehamberger H, Wolff K, Binder M (2002) Diagnostic accuracy of dermoscopy. Lancet Oncol 3:159–165

Lallas A, Argenziano G, Zendri E et al (2013) Update on non-melanoma skin cancer and the value of dermoscopy in its diagnosis and treatment monitoring. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther 13:541–558

Lallas A, Tzellos T, Kyrgidis A et al (2014) Accuracy of dermoscopic criteria for discriminating superficial from other subtypes of basal cell carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol 70:303–311

Lallas A, Apalla Z, Argenziano G et al (2014) The dermatoscopic universe of basal cell carcinoma. Dermatol Pract Concept 4:11–24

Rajadhyaksha M, Grossman M, Esterowitz D, Webb RH, Anderson RR (1995) In vivo confocal scanning laser microscopy of human skin: melanin provides strong contrast. J Invest Dermatol 104:946–952

Maier T, Kulichova D, Ruzicka T, Berking C (2014) Noninvasive monitoring of basal cell carcinomas treated with systemic hedgehog inhibitors: pseudocysts as a sign of tumor regression. J Am Acad Dermatol 71:725–730

Bennassar A, Carrera C, Puig S, Vilalta A, Malvehy J (2013) Fast evaluation of 69 basal cell carcinomas with ex vivo fluorescence confocal microscopy: criteria description, histopathological correlation, and interobserver agreement. JAMA Dermatol 149:839–847

Longo C, Rajadhyaksha M, Ragazzi M et al (2014) Evaluating ex vivo fluorescence confocal microscopy images of basal cell carcinomas in Mohs excised tissue. Br J Dermatol 171:561–570

Hartmann D, Ruini C, Mathemeier L et al (2016) Identification of ex-vivo confocal scanning microscopic features and their histological correlates in human skin. J Biophotonics 9(4):376–387

Agero AL, Busam KJ, Benvenuto-Andrade C et al (2006) Reflectance confocal microscopy of pigmented basal cell carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol 54:638–643

Guitera P, Menzies SW, Longo C et al (2012) In vivo confocal microscopy for diagnosis of melanoma and basal cell carcinoma using a two-step method: analysis of 710 consecutive clinically equivocal cases. J Invest Dermatol 132:2386–2394

Ulrich M, Roewert-Huber J, Gonzalez S et al (2011) Peritumoral clefting in basal cell carcinoma: correlation of in vivo reflectance confocal microscopy and routine histology. J Cutan Pathol 38:190–195

Acknowledgments

The authors thank MAVIG for providing the Reflectance Confocal Microscope Vivascope® 1500.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

C. Ruini and D. Hartmann share the first authorship

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ruini, C., Hartmann, D., Saral, S. et al. The invisible basal cell carcinoma: how reflectance confocal microscopy improves the diagnostic accuracy of clinically unclear facial macules and papules. Lasers Med Sci 31, 1727–1732 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10103-016-2043-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10103-016-2043-3