Abstract

Bacteraemia of unknown origin is prevalent and has a high mortality rate. However, there are no recent reports focusing on this issue. From 2005 to 2011, all episodes of community onset bacteraemia of unknown origin (CO-BSI), diagnosed at a 700-bed university hospital were prospectively included. Risk factors for Enterobactericeae resistant to third-generation cephalosporins (3GCR-E), Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus and Enterococcus spp, and predictors of mortality were assessed by logistic regression. Out of 4,598 consecutive episodes of CO-BSI, 745 (16.2 %) were of unknown origin. Risk factors for S. aureus were male gender (OR 2.26; 1.33–3.83), diabetes mellitus (OR 1.71; 1.01–2.91) and intravenous drug addiction (OR 17.24; 1.47–202); for P. aeruginosa were male gender (OR 2.19; 1.10–4.37) and health-care associated origin (OR 9.13; 3.23–25.83); for 3GCR-E was recent antibiotic exposure (OR 2.53; 1.47–4.35), while for enterococci, it was recent hospital admission (OR 3.02; 1.64–5.55). Seven and 30-day mortality were 8.1 % and 13.4 %, respectively. Age over 65 years (OR 2.13; 1.28–3.55), an ultimately or rapidly fatal underlying disease (OR 4.15; 2.23–7.60), bone marrow transplantation (OR 4.07; 1.24–13.31), absence of fever (OR 4.45; 2.25–8.81), shock on presentation (OR 10.48; 6.05–18.15) and isolation of S. aureus (OR 2.01; 1.00–4.04) were independently associated with mortality. In patients with bacteraemia of unknown origin, a limited number of clinical characteristics may be useful to predict its aetiology and to choose the appropriate empirical treatment. Although no modifiable prognostic factors have been found, management optimization of S. aureus should be considered a priority in this setting.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Bloodstream infections (BSI) remain a leading cause of morbidity and mortality [1] and are currently the 11th leading cause of death in the United States [2]. The latest studies on community-onset bacteraemia that encompass health-care-associated (HCA) and community-acquired (CA) bloodstream infections report an overall 30-day mortality of 13.5–20 % [3–5]. Bacteraemia of unknown origin represent between 9 and 22 % of all bacteremic episodes and are associated with increased mortality [4, 5] in comparison to those with a known source.

Appropriate empirical antibiotic treatment has been commonly associated with a better outcome in patients with bloodstream infections [6, 7]. Knowledge of the source of the infection usually helps in the selection of appropriate empirical treatment by narrowing the range of potential aetiological microorganisms.

There is limited data focusing on bacteraemia of unknown origin, despite its high frequency and mortality rate. Our group has been interested in this aspect in recent years [8], but since important changes in epidemiology of resistant microorganisms have been observed, we believe that it is essential to re-evaluate the issue. The objective of our study was to analyze the current clinical and microbiological characteristics and outcome of patients with community-onset bacteraemia of unknown origin with emphasis on predictors of Enterobactericeae resistant to third-generation cephalosporins (3GCR-E), Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus and Enterococcus spp.

Materials and methods

Study design

The study was conducted in a 700-bed university centre that provides specialized and broad medical, surgical, and intensive care for an urban population of 500,000 people. Since 1991 our unit has been prospectively identifying and monitoring all patients with bacteraemia admitted to our hospital. The present report refers to all adult patients (≥18 years old) with community-onset bacteraemia of unknown source recorded from January 2005 to December 2011. The Ethics Committee board of our institution approved the study.

Data collection and definitions

Assessed clinical variables

The following data were obtained from all patients: age, gender, comorbidities, McCabe classification of underlying diseases, treatment with antibiotics or steroids in the previous month, recent hospitalization (within the last month), surgery and other invasive procedures, origin of infection (community or health-care related), source of bacteraemia, shock on presentation, need for mechanical ventilation, etiologic microorganisms, empirical antibiotic treatment, appropriateness of empirical therapy, and mortality (evaluated at 7 and 30 days).

Definitions

Bacteraemic patients were prospectively followed up by a senior infectious disease specialist who assessed the patient’s medical history, physical examination, the results of other microbiological tests and complementary imaging explorations in order to determine the source of infection. An unknown origin was established when no source could be identified.

Community-onset bacteraemia refers to health-care-associated (HCA-BSI) and community-acquired (CA-BSI) bloodstream infections. HCA-BSI were defined as those with a first positive blood culture obtained ≤2 days from admission in patients having at least one of the following characteristics: (1) Being discharged within 30 days from an acute care hospital, (2) Receiving haemodialysis or any kind of intravenous therapy provided by a hospital-dependent facility within 30 days prior to the bloodstream infection, or (3) Residence in a nursing home or long-term care facility. CA-BSI were defined as those with a first positive blood culture obtained ≤2 days from admission and not fulfilling criteria for HCA-BSI.

Prior antibiotic therapy was defined as the use of any antimicrobial agent for ≥3 days during the month prior to the occurrence of the bacteraemic episode. Empirical therapy was considered appropriate when the initial regimen administered within the first 24 h after blood cultures and before knowing the susceptibility testing results was active in vitro against all the subsequent isolated bacteria and the dosage and route of administration were in accordance with the current medical standards.

Microbiological methods

During the study period, blood cultures were processed by the BACTEC 9240 system (Becton-Dickinson Microbiology Systems) with an incubation period of 5 days. Isolates were identified by standard techniques. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing was performed by using a microdilution system (Phoenix system [Becton, Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ] or Etest [AB Biodisk, Solna, Sweden]). Current Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) breakpoints for each year were used to define susceptibility or resistance to these antimicrobial agents, and intermediate susceptibility was considered as resistance.

Statistical analysis

Data from different groups of patients were compared using chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables and the Student t test or Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables. Patient’s characteristics or exposures with a P value of ≤0.20 in the univariate analysis were subjected to further selection by using a forward stepwise non-conditional logistic procedure, and the criteria for variables to step in and out the model were a P value of 0.05 and 0.10, respectively. To evaluate model calibration, the Hosmer-Lemeshow (H-L) test for goodness of fit was applied. The analysis was done by using the SPSS software (version 18.0; SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

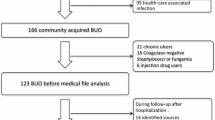

During the study period, out of 4,598 consecutive episodes of community-onset bacteraemia a total of 745 (16.2 %) were of unknown origin. Patient clinical characteristics are shown in Table 1. Almost all (93.6 %) patients had comorbidities with the most frequent being haematological malignancies, solid organ cancer, diabetes mellitus and liver cirrhosis.

Of all isolated organisms, 391 (52.5 %) were Gram-negative bacteria, 357 (47.9 %) Gram-positive, 10 (1.3 %) fungi, and 18 (2.4 %) polymicrobial (Table 2). E. coli, Klebsiella spp. and S. aureus (including methicillin-resistant strains) were equally prevalent in HCA-BSI and CA-BSI. P. aeruginosa and coagulase-negative staphylococci were more frequent in HCA-BSI while Listeria spp., Salmonella spp. and S. pneumoniae predominated in CA-BSI. Third-generation cephalosporin resistance in Enterobacteriaceae and beta-lactam and ciprofloxacin resistance in P. aeruginosa were more frequent in isolates involved in HCA-BSI episodes.

The results of univariate analysis of S. aureus, P. aeruginosa and 3GCR-E risk factors are shown in Table 3. In regards to S. aureus, the multivariate analysis selected male gender (OR 2.26; 1.33–3.83), diabetes mellitus (OR 1.72; 1.01–2.91) and intravenous drug addiction (OR 17.24; 1.47–201.98) as risk factors while neutropenia was protective (OR 0.25; 0.09–0.71). Independent predictors of P. aeruginosa were male gender (OR 2.19; 1.10–4.37) and HCA-BSI (OR 9.13; 3.23–25.83). For 3GCR-E, recent antibiotic exposure (OR 2.53; 1.47–4.35) was the only significant predictor, and for enterococci only recent hospital admission (OR 3.02; 1.64–5.55) was selected as an independent risk factor.

The overall 7 and 30-day mortality rate was 8.1 % (60 patients) and 13.4 % (100 patients), respectively. The highest rates of 7- and 30-day mortality by organism were observed among patients with bacteraemia due to Pseudomonas aeruginosa (18.2 %, 25 %), Staphylococcus aureus (17.9 %, 21.8 %) and Enterococcus spp. (4.4 %, 15.6 %). For P. aeruginosa and S. aureus, mortality was significantly higher than that associated with other microorganisms at both 7 (18.2 % vs 7.4 %, p = 0.019 and 17.9 % vs 6.9 %, p = 0.001, respectively) and 30 (25 % vs 12.7 %, p = 0.020 and 21.8 % vs 12.4 %, p = 0.022, respectively) days. It is of note that patients with 3GCR-E had the lowest 7-day mortality (1/59, 1.7 %), with a trend towards being significantly lower than that of episodes due to all other microorganisms (59/686, 8.6 %, p = 0.07) or to Enterobacteriaceae susceptible to third-generation cephalosporins (19/231, 8.2 %, p = 0.08). Empirical antibiotic treatment was inappropriate in 25.5 % of episodes, particularly in those due to 3GCR-E (42.4 % vs. 23.9 % for other episodes, p = 0.002) and enterococci (53.3 % vs. 23.6 % for other episodes, p < 0.001). Prevalence of inappropriate empirical treatment was not significantly different between survivors and non-survivors (25 % vs. 28 %, p = 0.52). Univariate and multivariate analysis of variables associated with 30-day mortality is shown in Table 4. Age over 65 years, having an ultimately or rapidly fatal underlying disease, bone marrow transplantation, absence of fever, shock on presentation and isolation of S. aureus were independently associated with 30-day mortality. The best model predicting 7-day mortality included the above mentioned variables plus isolation of 3GCR-E that entered the model as a protective factor (OR 0.06; 0.01–0.77). No interaction between appropriateness of empirical antibiotic treatment and etiologic microorganisms was found.

Discussion

According to the findings of the present study, an unknown focus of bacteraemia is still prevalent, occurs in patients with comorbidities, is commonly due to resistant or potentially resistant microorganisms and is associated with an appreciable mortality. Without the aid of a clinically apparent source, to assess the predictive features of individual organisms may be particularly important in order to design strategies aimed to improve empirical antibiotic therapy appropriateness.

The prevalence of bacteraemia of unknown source observed in the present study (16.2 %) agrees with the previously reported range (9–22 %) [3, 9–12]. Furthermore, the observed global distribution of microbial species is quite similar to that of many recent reports on community-onset bacteraemia [3, 10, 13, 14], although these did not specify the distribution of microbial species according to the source. The present study focused on bacteraemia of unknown origin and in comparison with previous studies there was, as expected, a lesser incidence of S. aureus and S. pneumoniae and a higher of Listeria spp. and Salmonella spp. In addition, P. aeruginosa isolates were almost exclusively observed in HCA-BSI, while S. pneumoniae and Salmonella spp. were mainly found in CA-BSI.

To our knowledge, only three studies have specifically focused on bacteraemia of unknown origin [8, 11, 12]. Two of them were carried out more than 10 years ago and included both community-onset and hospital-acquired episodes. The more recent study (2003–06) did not include neutropenic patients and was performed in a period when ESBL-producing enterobacteriaceae were still uncommon. In spite of these drawbacks, the global distribution of microbial species does not seem to have changed substantially over time. In the present study, E. coli was the most frequent isolated microorganism, either in HCA-BSI or in CA-BSI, followed by coagulase-negative staphylococci (CNS), Staphylococcus aureus, P. aeruginosa and S. pneumoniae. Not unexpectedly, the main difference with prior studies was that currently 20.3 % of Enterobacteriaceae were resistant to third-generation cephalosporins and 17.9 % of Staphylococcus aureus were methicillin-resistant.

Our findings confirm the results of previous studies [4, 5] which reported an appreciable mortality rate (12–29.4 %) in patients with bacteraemia of unknown origin. In the present study, fatal outcome was predicted by six factors: age older than 65 years, an ultimately or rapidly fatal prognosis of underlying disease, bone marrow transplant, no fever at admission, presence of shock at admission and S. aureus isolation. It is of note that factors associated with 7- and 30-day mortality were the same with the exception of 3GCR-E which was associated with less acute mortality. The latter observation is intriguing, and there is not a satisfactory explanation for it. The possibility of 3GCR-E being less pathogenic than their susceptible counterparts or other microorganisms ensues, but given the current knowledge of the complex relationship between resistance and virulence [15], it seems a rather speculative explanation that should be specifically assessed in further studies. All these prognostic factors have been previously mentioned [16–18] and none of them is potentially modifiable. Contrary to some previous reports [16, 19, 20], we could not find a significant association between 7- and 30-day mortality and inappropriate empirical treatment. This result might reflect recent improvements in microbiological diagnosis allowing an earlier administration of appropriate therapy. In spite of the present findings we believe that improving the management of S. aureus bacteraemia is still of crucial importance, which may include the use of empirical antibiotics that are not only “appropriate” by definition but optimal in terms of clinical efficacy.

In this study, we looked for clinical features predictive of infections caused by species that may require a particular therapeutic approach, namely, S. aureus, P. aeruginosa, 3GCR-E and Enterococcus spp. Male gender, diabetes mellitus and intravenous drug addiction were independently associated with S. aureus; HCA acquisition and male gender were predictors of P. aeruginosa, and for 3GCR-E and Enterococcus spp. the only independent risk factor was recent antibiotic therapy (within the last month) and prior hospital admission, respectively. All these clinical characteristics have been previously recognized as potential risk factors for the respective microorganisms [21–26], and may be useful to guide the selection of an appropriate empirical antibiotic regimen.

There is no consensus about the minimum prevalence of a given microorganism that would recommend the coverage for it by the empirical antibiotic regimen. Based on our criteria that empirical antibiotic treatment should be active against all microorganisms with a prevalence of at least 10 % (and probably of ≥5 % in cases of severe sepsis or septic shock), we propose some recommendations. In settings with an overall 6 % prevalence of 3GCR-E, cefotaxime or ceftriaxone may be appropriate for CA-BSI of unknown origin in non-diabetic women without prior antibiotic exposure. In our study, methicillin-sensitive S. aureus had 16.1 % prevalence in diabetic women, 10.9 % in men regardless of diabetes, and 66.7 % in intravenous illicit drug users. Hence, it may be advisable to provide empirical coverage against this organism to patients with these characteristics. Whether cefotaxime or ceftriaxone can be considered as an appropriate empiric therapy for methicillin-susceptible S. aureus bacteraemia is questionable. In a rabbit model of endocarditis, ceftriaxone 2 g once a day was less effective than cloxacillin [27], and there is some clinical evidence suggesting that for methicillin-sensitive S. aureus bacteraemia empiric treatment with a third-generation cephalosporin may be associated with a higher mortality rate than treatment with cloxacillin or cefazolin [28]. This may be due to the less intrinsic activity of ceftriaxone and cefotaxime against S. aureus (MIC50–90 = 4 mg/L) [29] and, therefore, increasing their dose (to at least 2 g of ceftriaxone or 6 g of cefotaxime per day), adding an isoxazolyl-penicillin or using ceftaroline [30], would be appropriate. In our series, MRSA was rare except in diabetic men, in whom a prevalence of 6 % was found. Therefore, empirical coverage for MRSA only for diabetic men with severe sepsis is suggested. In patients with CA-BSI of unknown source recently exposed to antibiotics, a 13 % prevalence of Enterobacteriaceae resistant to third-generation cephalosporins is of concern and ertapenem may be the most appropriate choice. In other circumstances (prevalence ≈ 5 %), a carbapenem should be only considered for patients with severe sepsis. According to the present data, P. aeruginosa is of concern only in patients with HCA infections, particularly in men regardless of recent antibiotic exposure, and coverage against enterococci may be considered for patients with recent hospital admission.

There are some limitations to our study. First, it was conducted in a single, tertiary-care hospital and, therefore, the results may have been influenced by local epidemiological variables and not applicable to other settings. Second, the presence or absence of a “Do Not Attempt Resuscitation” (DNAR) order was not recorded, and this might have limited an effective search for the source of bacteraemia in some patients. Third, our definition of prior antibiotic therapy was limited to the month preceding the BSI episode, and this may have contributed to blur a possible association of previous antibiotic exposure with resistant or potentially-resistant pathogens such as MRSA or P. aeruginosa. Last, the sample size is relatively large for a single-centre study but may still be too small to detect differences in outcome and risk factors for specific microorganisms.

In conclusion, a limited number of clinical characteristics may be useful to predict the microorganisms involved in bacteraemia of unknown origin and to choose the appropriate empirical treatment. Given the fact that S. aureus is an independent predictor of mortality, management optimization of this microorganism should be considered as a priority.

References

Bearman GML, Wenzel RP (2005) Bacteremias: a leading cause of death. Arch Med Res 36:646–659. doi:10.1016/j.arcmed.2005.02.005

Hoyert DL, Ph D, Xu J (2012) National vital statistics reports deaths: Preliminary data for 2011. National VitalStatistics Reports, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 61(6)1–52

Lark RL, Saint S, Chenoweth C, Zemencuk JK, Lipsky BA, Plorde JJ (2001) Four-year prospective evaluation of community-acquired bacteremia: epidemiology, microbiology, and patient outcome. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 41:15–22

Pedersen G, Schønheyder HC, Sørensen HT (2003) Source of infection and other factors associated with case fatality in community-acquired bacteremia—a Danish population-based cohort study from 1992 to 1997. Clin Microbiol Infect 9:793–802

Retamar P, López-Prieto MD, Nátera C, de Cueto M, Nuño E, Herrero M et al (2013) Reappraisal of the outcome of healthcare-associated and community-acquired bacteramia: a prospective cohort study. BMC Infect Dis 13:344. doi:10.1186/1471-2334-13-344

Leibovici L, Shraga I, Drucker M, Konigsberger H, Samra Z, Pitlik SD (1998) The benefit of appropriate empirical antibiotic treatment in patients with bloodstream infection. J Intern Med 244:379–386

Ibrahim EH, Sherman G, Ward S, Fraser VJ, Kollef MH (2000) The influence of inadequate antimicrobial treatment of bloodstream infections on patient outcomes in the ICU setting. Chest 118:146–155

Ortega M, Almela M, Martinez JA, Marco F, Soriano A, López J et al (2007) Epidemiology and outcome of primary community-acquired bacteremia in adult patients. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 26:453–457. doi:10.1007/s10096-007-0304-6

Vallés J, Calbo E, Anoro E, Fontanals D, Xercavins M, Espejo E et al (2008) Bloodstream infections in adults: importance of healthcare-associated infections. J Infect 56:27–34. doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2007.10.001

Rodríguez-Baño J, López-Prieto MD, Portillo MM, Retamar P, Natera C, Nuño E et al (2010) Epidemiology and clinical features of community-acquired, healthcare-associated and nosocomial bloodstream infections in tertiary-care and community hospitals. Clin Microbiol Infect 16:1408–1413. doi:10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.03089.x

Leibovici L, Konisberger H, Pitlik SD, Samra Z, Drucker M (1992) Bacteremia and fungemia of unknown origin in adults. Clin Infect Dis 14:436–443

Larsen IK, Pedersen G, Schønheyder HC (2011) Bacteraemia with an unknown focus: is the focus de facto absent or merely unreported? A one-year hospital-based cohort study. APMIS 119:275–279. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0463.2011.02727.x

Kollef MH, Zilberberg MD, Shorr AF, Vo L, Schein J, Micek ST et al (2011) Epidemiology, microbiology and outcomes of healthcare-associated and community-acquired bacteremia: a multicenter cohort study. J Infect 62:130–135. doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2010.12.009

Lenz R, Leal JR, Church DL, Gregson DB, Ross T, Laupland KB (2012) The distinct category of healthcare associated bloodstream infections. BMC Infect Dis 12:85. doi:10.1186/1471-2334-12-85

Beceiro A, Tomás M, Bou G (2013) Antimicrobial resistance and virulence: a successful or deleterious association in the bacterial world? Clin Microbiol Rev 26:185–230. doi:10.1128/CMR.00059-12

Vallés J, Rello J, Ochagavía A, Garnacho J, Alcalá MA (2003) Community-acquired bloodstream infection in critically ill adult patients: impact of shock and inappropriate antibiotic therapy on survival. Chest 123:1615–1624

Wester AL, Dunlop O, Melby KK, Dahle UR, Wyller TB (2013) Age-related differences in symptoms, diagnosis and prognosis of bacteremia. BMC Infect Dis 13:346. doi:10.1186/1471-2334-13-346

Pien BC, Sundaram P, Raoof N, Costa SF, Mirrett S, Woods CW et al (2010) The clinical and prognostic importance of positive blood cultures in adults. Am J Med 123:819–828. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2010.03.021

Kumar A, Ellis P, Arabi Y, Roberts D, Light B, Parrillo JE et al (2009) Initiation of inappropriate antimicrobial therapy results in a fivefold reduction of survival in human septic shock. Chest 136:1237–1248. doi:10.1378/chest.09-0087

Retamar P, Portillo MM, López-Prieto MD, Rodríguez-López F, de Cueto M, García MV et al (2012) Impact of inadequate empirical therapy on the mortality of patients with bloodstream infections: a propensity score-based analysis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56:472–478. doi:10.1128/AAC.00462-11

Bassetti M, Trecarichi EM, Mesini A, Spanu T, Giacobbe DR, Rossi M et al (2012) Risk factors and mortality of healthcare-associated and community-acquired Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia. Clin Microbiol Infect 18:862–869. doi:10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03679.x

Laupland KB, Ross T, Gregson DB (2008) Staphylococcus aureus bloodstream infections: risk factors, outcomes, and the influence of methicillin resistance in Calgary, Canada, 2000–2006. J Infect Dis 198:336–343. doi:10.1086/589717

Schechner V, Nobre V, Kaye KS, Leshno M, Giladi M, Rohner P et al (2009) Gram-negative bacteremia upon hospital admission: when should Pseudomonas aeruginosa be suspected? Clin Infect Dis 48:580–586. doi:10.1086/596709

Kang C-I, Chung DR, Peck KR, Song J-H (2012) Clinical predictors of Pseudomonas aeruginosa or Acinetobacter baumannii bacteremia in patients admitted to the ED. Am J Emerg Med 30:1169–1175. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2011.08.021

Rodríguez-Baño J, Picón E, Gijón P, Hernández JR, Ruíz M, Peña C et al (2010) Community-onset bacteremia due to extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli: risk factors and prognosis. Clin Infect Dis 50:40–48. doi:10.1086/649537

Cardoso T, Ribeiro O, Aragão IC, Costa-Pereira A, Sarmento AE (2012) Additional risk factors for infection by multidrug-resistant pathogens in healthcare-associated infection: a large cohort study. BMC Infect Dis 12:375. doi:10.1186/1471-2334-12-375

Gavaldà J, López P, Martín T, Gomis X, Ramírez JL, Azuaje C et al (2002) Efficacy of ceftriaxone and gentamicin given once a day by using human-like pharmacokinetics in treatment of experimental staphylococcal endocarditis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 46:378–384. doi:10.1128/AAC.46.2.000

Paul M, Zemer-Wassercug N, Talker O, Lishtzinsky Y, Lev B, Samra Z et al (2011) Are all beta-lactams similarly effective in the treatment of methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia? Clin Microbiol Infect 17:1581–1586. doi:10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03425.x

Flamm RK, Sader HS, Farrell DJ, Jones RN (2012) Summary of ceftaroline activity against pathogens in the United States, 2010: report from the Assessing Worldwide Antimicrobial Resistance Evaluation (AWARE) surveillance program. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56:2933–2940. doi:10.1128/AAC.00330-12

File TM, Wilcox MH, Stein GE (2012) Summary of ceftaroline fosamil clinical trial studies and clinical safety. Clin Infect Dis 55(3):S173–S180. doi:10.1093/cid/cis559

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by the “Fundación Máximo Soriano Jiménez” (Barcelona, Spain).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hernandez, C., Cobos-Trigueros, N., Feher, C. et al. Community-onset bacteraemia of unknown origin: clinical characteristics, epidemiology and outcome. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 33, 1973–1980 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-014-2146-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-014-2146-3