Abstract

Sixty-six cases of Q fever in adults, serologically confirmed by indirect immunofluorescence, were studied to analyze the epidemiological, clinical and therapeutic aspects of the disease. Eighty-three percent of the patients were male, and the mean age was 44.7 years. Contact with animals was recorded in 24 patients. The main clinical form of presentation was pneumonia (37 cases); eight patients had hypoxia, and five had respiratory failure. The empirical treatment consisted of macrolides in 36% of cases. Evolution was favorable in all cases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Q fever is a worldwide zoonosis caused by Coxiella burnetii. Its most common reservoirs are cattle, sheep and goats, and infection in humans occurs mainly after inhalation of contaminated aerosol particles of dust, earth or feces [1, 2]. Its characteristic clinical polymorphism leads to acute-form manifestations; chronic forms, especially endocarditis, are less frequent, but have a higher mortality rate [2].

Despite the fact that the zoonosis is endemic in many regions, there are few clinical references to Q fever; thus, we decided to review a series of 66 patients with the diagnosis of Q fever treated at our hospital.

Materials and Methods

The study was conducted at the Corporació Parc Taulí de Sabadell hospital in the province of Barcelona, Spain, from 1989 to 1999. The serologic inclusion criteria were as follows: (i) seroconversion, defined as the detection of specific antibodies against the phase II Coxiella burnetii antigen with ≥1/160 titres in the convalescence phase and negative serology in the acute phase; (ii) a fourfold or higher increase of titres between the acute phase and the convalescence phase; or (iii) single ≥1/160 titres (the cut-off point was determined after a seroprevalence study carried out in our area; results presented in part by SF at the VII Congreso SEIMC 1996 in Málaga, Spain).

Indirect immunofluorescence with phase II antigen pre-fixed on slides (Coxiella burnetii - Spot IF; bioMérieux, France) was used to detect Coxiella burnetii antibodies. Serological tests for Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Legionella pneumophila and Chlamydia pneumoniae were also performed. Patients with single positive titres ≥1/160 for Coxiella burnetii were excluded from the study if they showed seroconversion for Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Legionella pneumophila or Chlamydia pneumoniae.

The following criteria were used to classify the clinical presentation of infection: (i) the patient was considered to have pneumonia if there was a lung infiltrate on chest radiograph; (ii) hepatitis was identified if the patient's aspartate aminotransferase and/or alanine aminotransferase level(s) were more than twice as high as the reference value in our laboratory (31 U/l), without lung involvement; and (iii) isolated febrile syndrome was identified when fever was present without lung and hepatic involvement or other focus of infection.

Results and Discussion

During the 11-year study period, acute Q fever was diagnosed in 66 adult patients, 55 of whom were male. The mean age of the patients was 44.7 years±standard deviation (SD) 17.9. Most of the episodes (62.1%) were diagnosed in winter and spring. All patients resided in urban areas and eight had recently stayed in a rural area. Twenty-four of the patients reported having contact with domestic animals.

The initial clinical presentation of Q fever was pneumonia in 37 cases, hepatitis in 22, isolated febrile syndrome in five, pleuropericarditis in one and acute bronchial involvement in one. In three of the five patients with isolated febrile syndrome the infection was prolonged, i.e., >15 days. Table 1 shows the main clinical manifestations and analytical data of the 66 cases.

Among the 37 cases with pneumonia, the most frequent radiographic alterations were as follows: unilateral in 34 cases, single lobe or single segment alteration in 32, and alveolar pattern in 32, with a slight predominance of right (57%) and basal (51%) locations. Pleural effusion was observed in two patients, and another patient had a pulmonary cavity. Hypoxia was reported in eight patients and five patients developed respiratory failure.

Seroconversion for Coxiella burnetii occurred in 27.3% of the cases, with single titres ≥1/160 in 48.5% and a fourfold or higher increase of baseline titres in 24.2%. One patient showed seroconversion for both Coxiella burnetii and Mycoplasma pneumoniae, and another patient for Legionella pneumophila. A further patient with a fourfold increase of baseline titres of Coxiella burnetii showed seroconversion for Mycoplasma pneumoniae. The initial antibiotic treatment varied according to the clinical presentation (Table 2).

The mean duration of febrile episodes was 7 days (SD 3.2 days) for patients with pneumonia and 12.9 days (SD 5.7 days) for patients with hepatitis; fever lasted for more than 15 days in six patients. Among the patients with pneumonia, 86.5% were admitted to hospital, with an average stay of 11.3 days (SD 8.5 days). In comparison, 59.1% of patients with hepatitis were hospitalized, and they had a longer average stay (15.8 days, SD 8.4 days). No patient died.

Q fever may appear in epidemic outbreaks or in sporadic cases, such as those seen in our hospital. The known environmental resistance of Coxiella burnetii allows it to be transported far away from its original source. This could account for the appearance of Q fever cases in urban areas like ours, where an important percentage of patients fails to report direct contact with animals, and no clear seasonal predominance is found.

Seroprevalence studies conducted in Spain have found that this disease appears more frequently in rural areas [3] (where seropositivity may reach 82.3%) than in urban areas [4, 5] (where seropositivity ranges from 4.2% to 32.3%). In a seroprevalence study we conducted in the area of our hospital, we detected 15.3% seropositivity at titres ≥1/40 using the immunofluorescence technique for Coxiella burnetii. In 4.2% of the cases, titres were ≥1/160.

The most frequent clinical presentation of Q fever is febrile syndrome, either as a sole presentation or with pulmonary and/or hepatic involvement [1, 2, 6].The different clinical presentations could reflect different properties of the causative Coxiella burnetii strains; the form could also depend on the amount and route of inoculation, the geographic area, host factors and/or the study methodology [7]. The design of our study did not allow us to conclude which clinical presentation occurs most frequently in our area.

The general incidence of acute community-acquired pneumonia caused by Coxiella burnetii is usually lower than 6% [8, 9]. In Spain, the highest incidence is found in the Basque region, with 18.8% [10]. Although the course of disease is mild in most cases, between 7.3% and 15% of patients will develop respiratory failure, and around 40% will present with hypoxia [8, 10].

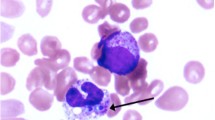

Cavitary infiltrates are rare. Nevertheless, a cavitary infiltrate was found on the chest radiograph of one of our patients ; this pattern does not rule out Coxiella burnetii as a possible etiology. Pleural effusion has also been described in patients with Q fever. It occurred in two of our patients, and in one series the incidence reached 17.6% [11]. Although expectoration is infrequent in atypical pneumoniae, it has been found in around 15% of patients in some series of pneumonia caused by Coxiella burnetii [10, 11]. In half of our patients with expectoration, hemoptysis also occurred.

Q fever with hepatic involvement presents as an acute febrile syndrome with headache and alteration of the patient's general status; hepatomegaly is the only focal sign, and hepatic biological parameters are only moderately altered [12]. One of our patients had pericarditis. Pericarditis caused by Coxiella burnetii is an infrequent disease, but its incidence is possibly underestimated since serological testing for Coxiella burnetii is generally only included routinely in cases of recidivating pericarditis [13].

Given the low number of specific symptoms and signs of Q fever, the diagnosis is reached retrospectively by serology. This explains why 13.6% of our patients were not treated with antibiotics after being asymptomatic at the time of diagnosis, and 28% of our patients received treatment that was not specific for Q fever. While doxycycline is the drug of choice for infections with Coxiella burnetii, only 12.1% of our patients (most of whom had hepatitis) were given this antibiotic. Macrolides were given to 73% of our patients with pneumonia as initial treatment (either alone or in association with a beta-lactam agent), with the intention of empirically covering those germs that most frequently cause atypical pneumonia in our area [9]. However, in areas where Q fever is highly endemic, and when epidemiological data supporting it are found, the empirical treatment of choice is doxycycline.

The role of macrolides in the treatment of Q fever pneumonia is controversial. Despite their ineffectiveness in vitro, the macrolides seem to have a bactericidal effect in vivo, and in our study, patients treated with a macrolide actually did recover favorably. The decision to use doxycycline instead of a macrolide to treat Q fever would be based on the fact that doxycycline shortens the febrile period rather than more effectively healing the infection [14, 15]. The good in vitro activity of new quinolones against Coxiella burnetii may change the empirical treatment of atypical pneumonia in the future.

References

Raoult D, Marrie T (1995) Q fever. Clin Infect Dis 20:489–495

Raoult D, Dupont HT, Foucalt C, Gouvernet J, Fournier P, Bernit E, Stein A, Nesri M, Harle JR, Weiller PJ (2000) Q fever 1985–1998. Clinical and epidemiologic features of 1383 infections. Medicine (Baltimore) 79:109–123

Pascual Velasco F, Montes M, Marimon JM, Cilla G (1998) High seroprevalence of Coxiella burnetii infection in eastern Cantabria (Spain). Int J Epidemiol 27:142–145

Ausina V, Sambeat MA, Esteban G, Luquín M, Condom MJ, Rabella N, Ballester F, Prats G (1988) Estudio seroepidemiológico de la fiebre Q en áreas urbanas y rurales de Cataluña. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin 6:95–101

Cour MI, Gonzalez MC, Gonzalez S, Palau ML, Gonzalez C, Ferro A (1990) Coxiella burnetii: Estudio serológico en distintas poblaciones. An Med Interna 7:513–516

Domingo P, Muñoz C, Franquet T, Gurguí M, Sancho F, Vazquez G (1999) Acute Q fever in adult patients: report on 63 sporadic cases in an urban area. Clin Infect Dis 29:874–879

Marrie TJ, Stein A, Janigan D, Raoult D (1996) Route of infection determines the clinical manifestations of acute Q fever. J Infect Dis 173:484–487

Lieberman D, Lieberman D, Boldur I, Manor E, Hoffman S, Schlaeffer, Porath A (1995) Q fever pneumonia in the Negev Region of Israel: a review of 20 patients hospitalized over a period of one year. J Infect 30:135–140

Sopena N, Sabrià M, Pedro-Botet ML, Manterola JM, Matas L, Domínguez J, Modol JM, Tudela P, Ausina V, Foz M (1999) Prospective study of community-acquired pneumonia of bacterial etiology in adults. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 18:852–858

Sobradillo V, Ansola P, Baranda F, Corral C (1989) Q fever pneumonia: a review of 164 community-acquired cases in the Basque country. Eur Respir J 2:263–266

Gikas A, Kofteridis D, Bourus D, Voloudaki A, Tselentis Y, Tsaparas N (1999) Q Fever pneumonia: appearance on chest radiographs. Radiology 210:339–343

Espaulella J, Elías J, Bella F, Armengol J, Segura F (1988) Fiebre Q: forma febril y hepática. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin 6:105–106

Levy PY, Carrieri P, Raoult D (1999)Coxiella burnetii pericarditis: report of 15 cases and review. Clin Infect Dis 29:393–397

Gikas A, Spyridaki I, Scoulica E, Psaroulaki A, Tselentis Y (2001) In vitro susceptibility of Coxiella burnetii to linezolid in comparison with its susceptibilities to quinolones, doxycycline, and clarithromycin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 45:3276–3278

Gikas A, Kofteridis D, Manios A, Pediaditis J, Tselentis Y (2001) Newer macrolides as empiric treatment for acute Q fever infection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 45:3644–3646

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sampere , M., Font , B., Font , J. et al. Q Fever in Adults: Review of 66 Clinical Cases. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 22, 108–110 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-002-0873-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-002-0873-3