Abstract

This study aims to identify potential factors that could affect adherence and influence the implementation of an evidence-based structured walking program, among older adults diagnosed with knee osteoarthritis. A total of 69 participants with mild to moderate osteoarthritis of the knee fulfilled an online survey on potential factors that could affect their adherence to an evidence-based structured walking program. Adherence with regard to the influencing factors was explored using a logistic regression model. Results tend to show higher odds of adhering to the evidence-based walking program if the participants were supervised (more than 2.9 times as high), supported by family/friends (more than 3.7 times as high), and not influenced by emotional involvement (more than 11 times as high). The odds of adhering were 3.6 times lower for participants who indicated a change in their medication intake and 3.1 times lower for individuals who considered themselves as less physically active (95 % confidence interval (CI)). Our exploratory findings identified and defined potential adherence factors that could guide health professionals in their practice to better identify positive influences and obstacles to treatment adherence, which would lead to the adoption of a more patient-centered approach. A large-scale study is required to clearly delineate the key factors that would influence adherence. We addressed a new knowledge gap by identifying the main strategies to promote the long-term adherence of community-based walking program.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA), a degenerative joint disease, frequently affects the knees. It is one of the most common causes of pain in older individuals [1]. Moderate-intensity physical activity, such as walking, is an effective intervention and has been linked to numerous health benefits [2]. However, people affected by this chronic health condition tend to avoid physical activity [3]. Therefore, it is essential to understand why this population commonly chooses to not adhere to a physical activity [4, 5] that could help circumvent the deleterious effects of OA on functional ability. As demonstrated in a recent systematic review of Loew et al. [2], studies involving physical activity interventions in individuals with OA reported low adherence rates ranging from 27 to 64 % [2]. Adherence is considered a key criterion to evaluate the therapeutic effectiveness of an exercise program. It refers to the extent to which a person follows and accepts a treatment recommended by health professionals [6, 7] and is able to successfully reach the therapeutic goals [7]. Poor adherence indicates that important internal as well as external barriers in the implementation or successful completion of a physical activity intervention exist. The success of implementing an evidence-based intervention may perhaps be affected by factors related to adherence [6]. Though previous researchers identified adherence factors impacting arthritis [8–10], a clear consensus of influencing factors to improve adherence has not yet been established. Thereby, there is a need to identify the factors related to adherence and to adopt new tailored strategies to promote the adherence of physical activity interventions or programs.

To date, there remains a significant gap in knowledge regarding the process through which individuals with OA fail to regulate physical activity over time. To address this knowledge gap, two main theoretical frameworks have been proposed to identify potential factors affecting adherence to physical activity in the management of chronic diseases [11–13]. The social cognitive theory of Bandura has shown that personal characteristics contribute to an individual’s level of motivation to adhere to physical activity [12–14]. Behavior is regarded as a reciprocal interaction between personal and environmental components [15]. The latter is defined as social or physical factors that facilitate or hinder behavior. Given the importance of these concepts, a framework pertaining to physical activity behavior change was developed by the World Health Organization (WHO) [13], based on the concepts of social cognitive theory [15]. The WHO published a conceptual framework to better illustrate how adherence is a multi-dimensional phenomenon not only defined exclusively by personal determinants but also by important environmental determinants [13]. In fact, adherence incorporates the broader notions of an external determinant called “concordance” (i.e., influence of the health professional on an individual’s treatment decision, while promoting harmony between the two parties) [16].

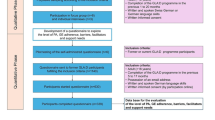

The five dimensions of adherence in this model illustrate that participant adherence is a multi-dimensional behavior construct, determined by five dimensions: (1) health system (e.g., community support, relationship with health professionals), (2) social/economic (e.g., social status, external environment), (3) therapy related (e.g., benefits, treatment effects), (4) condition related (e.g., illness related, level of physical/emotional disability), and (5) patient related (e.g., level of knowledge, beliefs) [13]. Therefore, this conceptual framework facilitates the theoretical understanding of adherence to physical activity behavior [13] and was used to guide the present study (see Fig. 1 for additional details).

Reproduced, with the permission of the publisher, from the World Health Organization ([13], Fig. 3, section II, chapter V, p. 41)

Concerns regarding adherence still persist, even when the effectiveness of a physical activity intervention has been established [2]. When participants are not engaged in the clinical decision-making, they may feel less empowered, resulting in decreased adherence [12]. The treatment preferences of individuals thereby need to be considered, allowing the participants to express themselves. In fact, the term “participant exercise preference” (PEP) refers to the individual’s personal expression of a value following consideration of benefits and risks of the interventions proposed, based on his/her values, beliefs, and needs [17]. PEP can be used as a knowledge transfer strategy to implement an evidence-based intervention. This strategy has not yet been applied to an aerobic walking program trial [18] nor has it been studied among older people with OA and investigated with adherence as the primary outcome [19]. Given these gaps and the relevance of the PEP factor, adherence is considered an essential outcome to successfully transfer evidence-based guidelines into clinical practice and patient care but remains challenging for stakeholders [20].

Aim

The general objective of the present study was to identify potential factors that could affect adherence and consequently influence the implementation of an evidence-based structured walking program [2], among older individuals diagnosed with mild to moderate knee OA. Since the primary outcome measured in the main study—The PEP trial [21]—was walking adherence, we expected to encourage OA participants to successfully adhere to an evidence-based effective walking program, by implementing a PEP strategy based on the evidence-based clinical practice guidelines [2]. In the present study, we evaluated three main research questions:

-

1.

Question 1: What are the most potential factors related to walking adherence?

-

2.

Question 2a: What are the five most potential factors that best describe each of the five dimensions of adherence, based on the WHO conceptual framework?

Question 2b: What is the potential influence of participants’ preference as it relates to walking adherence over and above the factors identified within each dimension of adherence, based on the WHO conceptual framework?

Materials and methods

Protocol

This study describes the findings from the first 3 months of a larger 9-month study using a preference study design [21]. The main objective of the larger study was to evaluate the effect of PEP, by examining the hypothesis that participants who followed their preferred intervention (supervised vs. unsupervised aerobic walking program) would be more likely to adhere throughout the 9-month study period. The inclusion criteria were participants (1) diagnosed with mild to moderate OA of the knee, (2) aged between 55 and 80 years old [1], (3) able to walk for a minimum of 20 min, (4) available to walk 3 times/week, and (5) give informed consent. A total of 69 adults were recruited (50 women (72.4 %) and 19 men (27.5 %)). Participants were stratified on whether they did or did not indicate a preference for supervision related to the walking program ((1) preference for supervised, (2) preference for unsupervised, or (3) no preference). The reader is referred to the larger study for a more detailed overview of the study methodology [21].

Primary outcomes

Walking adherence

Walking adherence was monitored as a percentage of the number of walking sessions attended and completed by each participant divided by the number of walking sessions recommended in the Ottawa Panel guidelines [2, 5]. Participants who completed at least on average two of three sessions (66 %) of the prescribed walking sessions per week were considered as adherent. This clinically relevant cut-off point was selected based on a previous physical activity study in which significant changes in health outcomes were demonstrated (e.g., improvement in pain, function, and overall health) among an OA population [22]. A review of aerobic activities for individuals with arthritis confirmed that walking demonstrated the highest clinical improvements with an adherence rate ranging between 68 and 88 %, compared with other modes of aerobic exercises (e.g., swimming, cycling, dance) [23]. To the best of our knowledge, only one study has used a participation threshold of 100 % [24].

Adherence factors

The purpose of this exploratory behavioral study was to identify factors that could potentially affect adherence and consequently influence the implementation of an evidence-based structured walking program [2]. To our knowledge, no detailed survey pertaining to physical activity adherence factors for individuals with knee OA has been published. To this end, a self-reported survey was developed based on two main sources.

To date, few studies have provide a thorough description of adherence factors, with the majority either only provided keywords for adherence concepts or described factors without developing a survey [6, 25–27]. Nonetheless, some adherence factors (e.g., self-efficacy, motivation) have been recognized in the literature [8–10, 12–14, 17, 18] and were considered to develop this self-reported survey.

Since the literature on determinants influencing adherence to walking programs for individuals with OA is very limited, participants were therefore asked to complete an initial evaluation. The participants had to identify (a) barriers that limit their participation in physical activity and (2) facilitators that help them engage in physical activity. These responses were integrated when developing the proposed survey on adherence factors.

Whether the adherence factors were identified from the literature or by the participants, they were categorized according to the WHO’s conceptual framework which integrates five key concepts (see Fig. 1) [13]: (1) social or economic, (2) health system, (3) therapy related, (4) condition related, and (5) patient related. See Table 1 for a list of all the potential adherence factors identified.

Data collection

Data were collected using the aforementioned survey. The compilation of data was verified independently by two members of the research staff. For the PEP, three types of preference were collected:

-

1.

Initial preference: at baseline, preference was evaluated where the participants had to respond “yes” or “no”: Do you have a preference for participating in a supervised or unsupervised walking program?

-

2.

Preferred choice: at baseline, the preferred choice was also examined, where the participants had to respond “yes” or “no”: Did you receive your preferred group?

-

3.

Preference at 3 months: participants enrolled in the study completed the online survey at 3 months after enrolment to a walking program. They responded whether the preference factor (“I was enrolled in my preferred group”) influenced their adherence to the study negatively (−1), had no impact (0), or positively (+1).

Data analyses

The data analysis focused on the evaluation of factors identified as most important to potentially predict the adherence of older adults diagnosed with knee OA participating in an evidence-based walking program. The dependent variable (adherence) was considered as a dichotomous binary variable since it was represented by two categories: 1, participant successfully attended and completed the walking program; 0, participant did not successfully attended but completed the walking program.

Adherence was influenced by variations in the independent variables, following a 3-point Likert ordinal scale: negative (−1), no impact (0), or positive (+1). This common rating scale was concise and allowed the participants to better express their opinion [28]. Adherence with regard to the influencing factors was determined using a polychotomous binary logistic regression model [29]. It evaluated the probability to adhere to the walking program in accordance to the explanatory variables, in this case, all the identified influencing factors. A multivariate analysis was performed using the variables that indicated a p value of ≤0.2 in order to identify the predictor variables, i.e., only the most important potential factors. As frequently selected in behavioral and social sciences research, this p value was used since a large number of categorical variables were entered in the equation [29]. Odds ratio could not be interpreted as a relative risk because adherence is not a rare event [29]. To be significant, the odds ratio of a factor needed to be in the range of 95 % (confidence interval (CI)), without including 1 within this range.

To assess research question 1, the most potential factors related to walking adherence were identified, among all the factors included in the online survey, using a univariate quantitative analysis to look at each factor separately. A set of the five most important variables reaching statistical significance was conserved.

To assess research question 2a, the five most important factors that best describe adherence were identified using a univariate analysis according to each dimension of adherence (WHO’s conceptual framework [13]). A set of the five most potential variables was taken to do a stepwise procedure (one factor represented each dimension). To assess research question 2b, we determined the importance of PEP related to walking adherence, in conjunction with the five same potential variables, selected in question 2a, in order to perform a stepwise procedure with the three types of preference.

The most important potential factors related to walking adherence were assessed based on all of the participants who adhered (successfully or not), and those who dropped out (n = 69) using the intention-to-treat approach, since the factors affecting an individual’s decision to drop out [30] were significantly related to the factors identified as important for adherence, as demonstrated by a Chi-square test (Chi-square = 39.403, p < 0.001). In light of the fact that 20 participants withdrew from the study at 3 months, secondary analyses were performed with the 49 participants who completed the 3-month intervention.

Results

At baseline, 54 out of 69 (78 %) participants indicated a preference for participating in a supervised (20/54 (37 %)) or unsupervised (34/54 (63 %)) walking program. Based on their stated exercise preference, participants were then assigned to one of the two modes of supervision for the effective walking program. Twenty-nine participants who indicated a preference were able to participate in their preferred walking supervision mode (54 %). Out of the 69 participants, 43 participants (62.3 %) successfully adhered to the walking program.

Among the 20 participants (18 women) who dropped out within 3 months, 19 did not adhere successfully prior to dropping out (95 %). At baseline, 95 % (19/20) of the participants indicated a preference for participating in a supervised or unsupervised walking program, and 11 of them who stated a preference did not obtain their preferred group after being assigned (58 %).

Since the range of value (95 % CI) included 1 in the results, evidence of the odd ratios was not statistically significant and tendencies were therefore suggested for each factor that were potentially important. By using the intention-to-treat approach, the most potential factors related to adherence were identified, at 9 months (p value ≤0.2): (1) change in medication use, (2) work/volunteering schedule, and (3) fear (fear of falling, walking causing pain). Results indicated a tendency that participants were 20 % less likely to adhere if change in medication use (p value, 0.236) and work/volunteering schedule (p value, 0.158) both represented a negative influence. Participants were 31 % less likely to adhere if their fear of falling negatively impacted their walking adherence (p value, 0.117) (see Table 2).

With regard to the 49 participants who completed the study at 3 months, 42 (85.7 %) successfully adhered to the walking program. Thirty-five (71 %) participants indicated a preference for participating in a supervised or unsupervised walking program, in which 21 of them were able to participate in their preferred group (60 %). At the end of the study program, the majority of participants (90 %) specified that participating in their preferred group had a positive influence on their adherence (44/49).

Table 3 shows the results according to research question 1. The five most important factors potentially influencing the adherence rate as determined from the survey response at 3 months were (p value ≤0.2) (1) level of satisfaction during walking and (2) emotional involvement. Specifically, participants were 3.4 times more likely to adhere if their level of satisfaction influenced their walking adherence in a positive way (p value, 0.293) Moreover, we observed a tendency that people were 53 % less likely to adhere to the walking program if they characterized the factor “emotional involvement” (i.e., attitude and unbearable emotions toward physical activity) as having a negative influence on their adherence.

With regard to research question 2a, the five most important potential factors influencing walking adherence representing each adherence dimension [13] were (p value ≤0.2) (see Table 4):

-

(A)

Environmental factors:

-

1.

Health system: participants were 2.9 times more likely to adhere if they felt being supervised by an exercise therapist had a positive impact on adherence (p value, 0.230).

-

2.

Social/economic: participants who indicated that family or friend support had no impact on their walking adherence were 3.7 times more likely to adhere (p value, 0.246).

-

3.

Therapy related: participants were 3.6 times less likely to adhere if they perceived a change in their medication use during the study. It seemed to have a negative influence on their adherence since it was a sign of more pain or additional health problems (p value, 0.073).

-

(B)

Personal factors:

-

(i)

4. Condition related: participants were 3.1 times less likely to adhere if they considered their physical fitness level as a negative influence on walking adherence (p value, 0.191).

-

(ii)

5. Patient related: participants were 11 times more likely to adhere if unbearable feelings, to the point of losing one’s ability, had no influence on their walking adherence (p value: 0.133).

With respect to research question 2b, Table 4 details the influence of preference compared with the five most potential adherence factors identified above (according to each dimension of adherence; p value ≤0.2). Preference was not considered the most important factor; it pertained to medication use and emotional involvement. The logistic regression revealed a tendency that participants who indicated a strong preference for being supervised or unsupervised were 46 % less likely to adhere if emotional involvement seemed to have a negative influence on walking adherence, in comparison with preference at baseline. Participants who had a preference and did not obtain their choice were 49 % less likely to adhere if again the factor “emotional involvement” had a negative influence on their adherence. At 3 months, results showed a tendency that participants were 77 % less likely to adhere if change in medication use had a negative influence on adherence.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to identify factors that could potentially affect adherence and consequently influence the implementation of an evidence-based structured walking program [2], among older adults diagnosed with knee OA. We found that the five following most potential factors were deemed important to walking adherence and were therefore linked to the overall success of the walking program: participants’ (1) level of satisfaction during walking, (2) emotional involvement, ( 3) fear, (4) physical fitness level, and (5) change in medication use.

It has been established that adherence to physical activity is a multi-dimensional behavior construct, determined by the interaction between five dimensions of adherence [13]. The conceptual framework by the WHO [13] stipulates that physical activity behavioral change is influenced by both personal determinants and environmental factors, without identifying precise factors to better understand each dimension of adherence. Preliminary results delineate the key factors that had a greatest influence on adherence to physical activity in the context of the five dimensions. This was an innovative feature of the study, as it was never examined in studies with people diagnosed with OA. These are as follows:

-

(A)

Environmental factors:

-

1.

Health system: supervision by exercise therapists’ seemed to have a positive impact on the participant’s adherence.

-

2.

Social/economic: adherence seemed to be positively influenced if the participant received support from his family or friends.

-

3.

Therapy related: change in the medication use seemed to negatively influence the participant’s adherence.

-

(B)

Personal factors:

-

4.

Condition related: high physical fitness level seemed to positively affect adherence.

-

5.

Patient related: absence of emotional involvement seemed to have a positive impact on the participant’s adherence.

The implementation of the innovative strategy using PEP was essential to address the recommendations of the Ottawa Panel guidelines, in order to successfully transfer evidence-based clinical practice guidelines into clinical practice [20]. Even though preference was not considered the most important factor, walking adherence was dependent on the PEP. Participants who stated that preference had a positive influence, were two times more likely to adhere (n = 69). Preference should be considered as an important influencing factor related to dropout as well as adherence.

This exploratory study supports the results of other studies examining adherence and drop out related to physical activity programs [17–19, 31]. Crandall et al. [32] suggested that considering preference when determining which type of intervention the participant should follow, can improve adherence. Our aforementioned findings are in accordance with those of Henry et al.’s [33] since, the authors confirmed that perception of individual physical capacity, beliefs about physical activity and motivational approaches should be considered and examined when working with a physical activity population as they can influence their behavior [33]. According to several other authors, self-efficacy [14, 25, 34] and motivation [25, 34–39] are factors that can significantly influence adherence, albeit these same factors did not reach statistical significance in our analyses even though they were evaluated.

Moreover, a new observation emerged from the analyses. Participants who perceived a change in their medication use during the study seemed to adhere poorly. It is plausible that a change in their medication prescription implies poorer health status, and as a consequence, they do not view physical activity as being able to provide any health benefits. Without perceived benefits on health or beliefs in physical activity, individuals tend to be less motivated, which influences their adherence. More research is warranted to examine this observation.

This study was novel in that it considered many factors to potentially impact adherence to physical activity, and a quantitative methodology was used to define the relative importance of each of these potential factors. However, since the majority of the factors influenced each other, a strong multicollinearity could be noticed, which may have decreased the significance of each factor. A strong multicollinearity increases the standard error and confidence intervals for the coefficients. Thus, multicollinearity may have to lead to some statistically non-significant analyses. To address this issue, a multivariate analysis commonly employed in behavioral and social sciences research was performed using only the variables that indicated a p value of ≤0.2, in order to identify the predictor variables, i.e., most potential factors. This p value was selected since a large number of categorical variables were entered in the equation. While the sample size was relatively small, a power calculation was performed prior to the study to justify the sample size. Our findings allowed for the development of a new relevant survey that can guide health professionals in their practice. The survey can be used by health professionals to assess their patients’ perceptions regarding adherence factors, and therefore adopt a more patient-centered approach. Ultimately, the goal is to help researchers and health care providers to better promote long-term adherence to a physical activity program and manage these potential factors in order to enable individuals with mild to moderate OA of the knee to participate in these exercise programs. Health professionals should also assess and respect their patients’ preferences for treatments [40, 41]. This will, in turn, allow the health care practitioners to adopt a patient-centered approach, to better accommodate the need of their patients, and increase their chance of success [41].

Conclusion

This exploratory study identified different potential factors, such as supervision, social support, medication use, fitness level, and emotional involvement that can influence walking adherence in clinical practice and research. Future studies should adopt an equally rigorous methodology, but factors which are inter-related and have strong associations should be removed (by performing a multicollinearity test) to avoid multi-collinearity and a larger sample size must be considered to confirm the factors that influence adherence.

In conclusion, there are many factors influencing adherence to walking program designed specifically for individuals with knee OA. These should be considered when developing physical activity interventions with this population. The most important ones included emotional involvement, mode of supervision, family/friends support, medication intake, and physical fitness level.

References

Klippel JH, Stone JH, Crofford LJ, et al. (2008) Juvenile idiopathic arthritis. In: Primer on the rheumatic diseases (Eds.), Chapter 7, 13th edn. Springer (CB Lindsley), Arthritis Foundation, USA, pp 166–167

Loew L, Brosseau L, Wells GA, Tugwell P, Kenny GP, Reid R, Maetzel A, Huijbregts M, McCullough C, De Angelis G, Coyle D, Panel Ottawa (2012) Ottawa Panel evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for walking programs in the treatment of osteoarthritis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 69:1269–1284

Dunlop DD, Song J, Semanik PA, Chang RW, Sharma L, Bathon JM, Eaton CB, Hochberg MC, Jackson RD, Kwoh CK, Mysiw WJ, Newitt NC, Hootman JM (2011) Hochberg measurement in the osteoarthritis initiative: are guidelines being met? Arthritis Rheum 63(11):3372–3383

Bombardier C, Hawker G, Mosher D (2011) The impact of arthritis in Canada: today and over the next 30 years. Arthritis Alliance of Canada: 1–52

Messier SP (2009) Obesity and osteoarthritis: disease genesis and nonpharmacologic weight management. Med Clin North Am 93(1):145–159

Jordan JL, Holden MA, Mason EEJ, Foster NE (2010) Interventions to improve adherence to exercise for chronic musculoskeletal pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 1(CD005956):1–60

Hoogeboom TJ, Oosting E, Vriezekolk JE, Veenhof C, Siemonsma PC, de Bie RA, van den Ende CH, van Meeteren NL (2012) Therapeutic validity and effectiveness of preoperative exercise on functional recovery after joint replacement: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 7(5):1–13

Rosella LC, Fitzpatrick T, Wodchis WP, Calzavara A, Manson H, Goel V (2014) High-cost health care users in Ontario, Canada: demographic, socio-economic, and health status characteristics. BMC Health Serv Res 14:532–538

Lunsky Y, Balogh RS, Cobigo V, Isaac B, Lin E, Ouellette-Kuntz HM (2014) Primary care of adults with developmental disabilities in Ontario. Healthcare Q 17(3):11–13

Poitras S, Rossignol M, Avouac J, Cedraschi C, Nordin M, Rousseaux C, Rozenberg S, Savarieau B, Thoumie P, Valat JP, Vignon E, Hilliguin P (2010) Management recommendations for knee osteoarthritis: how usable are they? Joint Bone Spine 77(5):458–465

Slovenic D’Angelo M, Reid RD (2007) A model for exercise behavior change regulation in patients with heart disease. J Sport Exerc Psychol 29:208–224

Rothman AJ, Baldwin AS, Hertel AW (2004) Self-regulation and behavior change: disentangling behavioral initiation and behavioral maintenance. In: Baumeister R, Vohs K (eds) Handbook of self-regulation: research, theory, and applications. Guilford Press, New York, USA, pp 130–148

WHO (2003) Adherence to long-term therapies—evidence for action. Noncommunicable diseases and mental health adherence to long term therapies project. Report. Report World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland

Sirur R, Richardson J, Wishart L, Hanna S (2009) The role of theory in increasing adherence to prescribed practice. Physiother Can 61:68–77

Bandura A (1986) Social foundations of thought and action: a social cognitive theory. Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs

Aronson JK (2007) Compliance, concordance, adherence. Br J Clin Pharmacol 63(4):383–384

Miranda J (2009) An exploration of participants’ treatment preferences in a partial RCT. CJNR 41(1):276–290

Tilbrook H (2008) Patients’ preferences within randomised trials: systematic review and patient level of meta-analysis. BMJ 337(a1864):1–8

Waynes G, Klippel JH (2010) A National Public Health Agenda for Osteoarthritis. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Arthritis 1–62

Stoneking L, Denninghoff K, Deluca L, Keim SM, Munger B (2011) Sepsis bundles and compliance with clinical guidelines. J Intensive Care Med 26(3):172–182

Loew L, Kenny GP, Durand-Bush N, Poitras S, Wells GA, Brosseau L (2014) The implementation of an effective aerobic walking program based on Ottawa panel guidelines for older individuals with mild to moderate osteoarthritis: a participant exercise preference pilot randomized clinical protocol design. Br J Med Med Res 4(18):3491–3511

King AC, Kiernan M (1997) Can we identify who will adhere to long-term physical activity? Signal detection methodology as a potential aid to clinical decision making. Health Psychol 16(4):380–389

Westby MA (2001) A health professional’s guide to exercise prescription for people with arthritis: a review of aerobic fitness activities. Arthritis Care Res 45(6):501–511

Tran CS, Kong Y, Gupta A (2013) Long-term exercise adherence after completion of the diabetes aerobic and resistance exercise (DARE) trial. Can J Diabetes 37(S4):S50–S51

Damush TM, Perkins SM, Mikesky AE (2005) Motivational factors influencing older adults diagnosed with knee osteoarthritis to join and maintain an exercise program. J Aging Phys Act 13:45–60

McAuley E, Jerome GJ, Marquez DX, Elavsky S, Blissmer B (2003) Exercise self-efficacy in older adults: social, affective, and behavioural influences. Ann Behav Med 25(1):1–7

Shih M, Hootman JM, Kruger J, Helmick CG (2006) Physical activity in men and women with arthritis. Am J Prev Med 30(5):385–393

Weijters B, Cabooter E, Schillewaert N (2010) The effect of rating scale format on response styles: the number of response categories and response category labels. Int J Res Mark 27(3):236–247

Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S, Sturdivant RX (2013) Applied logistic regression. John Wiley and Sons, 3rd edn

Stiggelbout M, Hopman-Rock M, Tak E, Lechner L, van Mechelen W (2005) Dropout from exercise programs for seniors: a prospective cohort study. J Aging Phys Act 13:409–421

Preference Collaborative Review Group (2008) Patients’ preferences within randomised trials: systematic review and patient level meta-analysis. Br Med J 337:1–8

Crandall S, Howlett S, Keysor SJ (2013) Exercise adherence interventions for adults with chronic musculoskeletal pain. Phys Ther 93(1):17–21

Hendry M, Williams NH, Markland D, Wilkinson C, Maddison P (2006) Why should we exercise when our knees hurt? A qualitative study of primary care patients with osteoarthritis of the knee. Fam Pract 23:558–567

Hutton I, Gamble G, McLean G, Butcher H, Gow P, Dalbeth N (2010) What is associated with being active in arthritis? Analysis from the obstacles to action study. Intern Med J 40(7):512–520

Ehrlich-Jones L, Lee J, Semanik P, Cox C, Dunlop D, Chang RW (2011) Relationship between beliefs, motivation, and worries about physical activity and physical activity participation in persons with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res 63(12):1700–1705

Hurkmans EJ, Maes S, de Gucht V, Knittle K, Peeters AJ, Ronday HK, Vlieland TP (2010) Motivation as a determinant of physical activity in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res 62(3):371–377

Jones M, Jolly K, Raftery J, Lip GY, Greenfield S, BRUM Steering Committee (2007) ‘DNA’ may not mean ‘did not participate’: a qualitative study of reasons for non-adherence at home- and centre-based cardiac rehabilitation. Fam Pract 24(4):343–357

Kehn M, Kroll T (2009) Staying physically active after spinal cord injury: a qualitative exploration of barriers and facilitators to exercise participation. BMC Public Health 9:168

Lee J, Dunlop D, Ehrlich-Jones L, Semanik P, Song J, Manheim L, Chang RW (2012) Public health impact of risk factors for physical inactivity in adults with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res 64(4):488–493

O’Hea EL, Wood KB, Brantley PJ (2003) The transtheoretical model: gender differences across 3 health behaviors. Am J Health Behav 27(6):645–656

Rich E, Lipson D, Libersky J, Peikes DN, Parchman M (2012) Organizing care for complex patients in the patient-centered medical home. Ann Fam Med 10(1):60–62

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to the Chair of the thesis examination committee Dr. Mary Egan (Epidemiologist), study participants, research staff (Amélie Gravelle, Valérie Langlois, Lisa Lévesque, Isabel Théberge, Ana Lakic, Prinon Rahman, David Li, Christine Smith, Spencer Yam), members of the Pacesetters Walking Club, Marion D.-Russell from the Arthritis Society, and Billings Bridge Shopping Centre staff. The proposed study was supported by the Arthritis Health Professions Association (AHPA) and The Arthritis Research Foundation Movement and Mobility. It was awarded the 2012 Arthritis Research Foundation Movement and Mobility Award. Other funds that were obtained include the following: scholarships from the Fonds de recherche en santé du Québec (FRSQ), University of Ottawa Research Chair, Knowledge Translation Canada, in collaboration with the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), Ontario Physiotherapy Association (OPA), Government of Ontario, and the University of Ottawa.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

This proposed study was in accordance with ethical standards for human research and was approved by the Research Ethics Board from the University of Ottawa (H01-07-08C).

Disclosures

None.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM 1

(DOCX 23 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Loew, L., Brosseau, L., Kenny, G.P. et al. Factors influencing adherence among older people with osteoarthritis. Clin Rheumatol 35, 2283–2291 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-015-3141-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-015-3141-5