Abstract

The aim of this study is to gain insight into arthritis patients’ motives for (not) wanting to be involved in medical decision-making (MDM) and the factors that hinder or promote patient involvement. In-depth semi-structured interviews were conducted with 29 patients suffering from Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA). Many patients perceived the questions about involvement in MDM as difficult, mostly because they were unaware of having a choice. Shared decision-making (SDM) was generally preferred, but the preferred level of involvement varied between and within individuals. Preference regarding involvement may vary according to the type of treatment and the severity of the complaints. A considerable group of respondents would have liked more participation than they had experienced in the past. Perceived barriers could be divided into doctor-related (e.g. a paternalistic attitude), patient-related (e.g. lack of knowledge) and context-related (e.g. too little time to decide) factors. This study demonstrates the complexity of predicting patients’ preferences regarding involvement in MDM: most RA patients prefer SDM, but their preference may vary according to the situation they are in and the extent to which they experience barriers in getting more involved. Unawareness of having a choice is still a major barrier for patient participation. The attending physician seems to have an important role as facilitator in enhancing patient participation by raising awareness and offering options, but implementing SDM is a shared responsibility; all parties need to be involved and educated.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In recent years, patients have been increasingly encouraged to take up an active role in managing their health and in medical decision-making (MDM). Patient empowerment, participation, involvement and shared decision-making (SDM) are frequently used concepts in this context [1–6]. Patient involvement in MDM is considered to be a patient’s right [7], but it has also been positively associated with satisfaction with care, self-management, coping behaviour and adherence [8–11].

While the benefits of participating in care and MDM have been widely reported, some studies have shown that not all patients want to be actively involved [3, 12–21]. Other studies have identified barriers for involvement in MDM. Unawareness of having a choice, low confidence in the capacity to participate, a perceived lack of knowledge and uncertainty about which questions to ask are among the barriers mentioned by patients [22–26].

Patients’ preferences regarding involvement in MDM have been explored in some depth for irreversible decisions like screening or surgery [15, 18–20, 27–29] but are less well known for decisions concerning chronic health problems, such as arthritis, where the doctor-patient relationship is potentially a long-term one [30]. In managing arthritis, the decision-making process has become increasingly complex due to the rapid development of new disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs). Including patients’ preferences in these decisions is important as these medications often have serious implications for patients’ lives due to the way of administration, the need for continued monitoring, and/or the risk of serious side effects. Moreover, because the success of treatment largely depends on a patient’s willingness to adhere to the medication, the treatment needs to closely fit in with the patient’s values and lifestyle.

To date, only a few studies have examined patients’ preferences regarding involvement in treatment decision-making in rheumatology. These studies showed that a large number of patients want to be involved in SDM, yet the percentages varied from 42 to 83 % across studies [3, 12, 14, 31]. Differences in patient populations, in the way of questioning and in the type of medical decision to be taken, may be responsible for the observed variation. Moreover, as most of these studies have used quantitative designs, the focus was predominantly on the amount of preferred influence, rather than on the patients’ motives for the preferred type of decision-making. More knowledge about patients’ motives for (not) wanting to participate in MDM and the factors that hinder or promote participation can make it easier for health-care professionals to pursue the preferred level of patient involvement. The aim of this study was to gain insight into rheumatic patients’ notions about involvement in MDM, by using a qualitative study design using in-depth interviews.

Methods

Recruitment of respondents

Patients were recruited from two hospitals in The Netherlands: Medisch Spectrum Twente (MST) and Ziekenhuisgroep Twente (ZGT). Patients diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) scheduled to have an appointment with the rheumatologist were preselected by one of the researchers. Rheumatologists were instructed to invite all these preselected patients to participate in the study if they had the ability to complete an interview in Dutch without assistance. After having been informed about the aim and procedure of the study, patients were asked to sign an informed consent form. Thirty patients initially consented to participate in the study, and one respondent cancelled the appointment due to being too ill.

Procedures

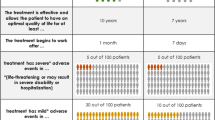

Semi-structured interviews were conducted by the first author (IN). The interviews, which lasted approximately 60 min each, were audiotaped and took place at patients’ homes or at the university. First, respondents were asked to describe the decision-making process of a recent medical decision related to the treatment of their RA that was highly important to them. Next, respondents were asked if they had participated in the decision-making process—and if so, how—or, if this was not the case, if and how they would have preferred to have participated in the decision-making process. Subsequently, the Control Preferences Scale (CPS) [32] was used to grade the level of preferred and perceived participation. The CPS consists of five cards portraying five different roles patients can assume in treatment decision-making, each role being described by a statement and a cartoon. Respondents were asked to pick one that portrayed their preferred role and motivate their choice. If they preferred to actively participate in MDM, they were asked whether they had been able to take on their preferred role during the recent decision-making process—and if this was not the case, which role they perceived to have had. In addition, respondents were asked which factors facilitated or hindered their participation. Patients were also invited to elaborate on their preferences and barriers and facilitators for participation in other treatment decisions related to their RA. The last five interviews identified no significant new themes, indicating that data saturation had occurred.

Data analysis

Data were analysed using inductive analyses. This means that the patterns, themes and categories of analysis arose from the data [33]. After verbatim transcription of the audiotaped interviews, two analysts (IN and CHD) independently read ten of the transcripts several times to familiarise themselves with the data. They identified emerging themes and selected relevant quotations (sentences or small paragraphs). Then, the two analysts compared and discussed their findings to develop a thematic framework. Relevant quotations were selected from the rest of the transcripts by the first author. These quotations were then grouped by three researchers (IN, CHD and ET) independently using the thematic framework. After every ten interviews, the researchers met to discuss their findings until consensus was reached. Themes were refined and subthemes were determined until a final thematic framework was developed. All quotations provided in this article were reviewed by a translator.

Findings

Respondent characteristics

A total of 19 women and 10 men all suffering from rheumatoid arthritis were recruited from nine different rheumatologists. The average age of the respondents was 56 years (range = 17–74 years), and most respondents had a low or medium level of education (n = 15 and 9, respectively). The majority of respondents was not employed (n = 22). The average disease duration was 8 years (range = 0–38 years). The current medication of patients was either traditional DMARDs (n = 20) or biologic DMARDs combined with methotrexate (n = 9).

A difficult concept

Overall, respondents appeared to have some difficulty in determining their experiences with and preference regarding involvement in MDM. They frequently hesitated in providing an answer or changed their answer during the interview. Many statements were qualified by “I think…” or “Maybe…” and several respondents mentioned literally: “Those are difficult questions”. Other patients mentioned that they had never thought about it: “I never thought about that, but after having this conversation with you I am going to ask more questions.” [Male, 66 years] or that they felt they did not have a choice: “My involvement? Did I have a choice?” [Male, 44 years]. Some patients had difficulties conceptualising patient involvement in MDM and gave somewhat ambiguous answers. For example, one respondent stated: “We do that together. He prescribes the medicine and I take it. […] That’s the way it is. I don’t know how else to explain it.” [Female, 69 years]. Someone else was convinced that the doctor made the decision: “The rheumatologist made that decision.” But shortly after, she showed to have (obliviously) influenced the decision and decision-making process: “And he was very much aware of the fact that I did not want prednisolone.” [Female, 41 years].

Patients’ preferences regarding involvement in MDM

Patients’ preference to let the doctor decide

Despite considering it a difficult question, most patients were able to indicate their preference for participation regarding involvement in MDM. A small but considerable group of respondents (n = 8) preferred the doctor to decide about which treatment to initiate. Trust in their doctor and valuing the expertise of the doctor were the main reasons for preferring not to be actively involved in MDM, as illustrated by this quotation: “I think highly of the medical profession. I trust them.” [Male, 64 years]. Patients who valued the expertise of the doctor mentioned that being well informed, being listened to and having their problems taken seriously were important prerequisites for satisfaction with this form of decision-making: “She decides, but I insist that she takes it… takes me seriously.” [Female, 61 years].

Patients’ preference to decide mostly by themselves

Only a few respondents (n = 3) wanted to decide mostly by themselves. One patient stated that she herself feels her symptoms best: “Well, for example, if I get side effects, then I believe I should be the one to decide whether or not to continue taking the medication, because I feel my body best.” [Female, 62 years]. Another patient wanted to be involved because she wanted to evaluate the consequences the decision would have for his personal situation: “I have a family and I do not want to be hospitalised for a few months. I weigh up the pros and cons, I decide that.” [Female, 41 years]. Finally, one patient simply wanted to be in control: “I am in control over my own body. If there is a decision at stake, I decide by myself. I do not need anybody else to help me.” [Female, 74 years].

Patients’ preferences for shared decision-making

Most respondents (n = 17) preferred shared decision-making (SDM), because it reflects a good relationship with the doctor, as illustrated by this quotation: “I want to share in the decision-making process. That he listens carefully to what you have to say and that you listen to his arguments as well. And that you can say anything, even small things, without feeling a bore. That’s when you have a good relationship.” [Female, 60 years]. Other reasons for this preference were mostly a combination of the aforementioned reasons for preferring the doctor to decide and the reasons to decide by themselves. For example, many respondents valued the expertise of the doctor highly but wanted to be a part of the decision-making process because they themselves feel their symptoms best, wanted to have some level of control or wanted to critically evaluate the impact the doctor’s advice would have on their personal situation and discuss this. The following quotation illustrates this last issue: “I want to share in the decision-making process. As a patient, you should follow the doctor’s advice, you should not say it is nonsense, you cannot do that, but I do critically evaluate his advice. […] And if I do not agree or have questions, well, then I discuss this with him.” [Male, 56 years].

Some patients were attracted to the notion of shared responsibility for the treatment: “It is about you, you are responsible for your own body, but because you do not have the knowledge, you also depend on the doctor, so he needs to be responsible as well. So you share the decision-making.” [Male, 50 years]. However, others did not agree with the shared responsibility. Although they did prefer SDM, they wanted the doctor to be responsible for the outcome of the treatment. “He is the expert and, in the end, it’s his responsibility. He is the one who is truly responsible, but we decide together.” [Female, 54 years].

Patients’ preferences regarding involvement vary according to the circumstances

Some respondents noted that their preference regarding involvement in medical decision-making depends on the occasion. They mentioned that their preference may depend on the type of treatment and the severity of their complaints (Box 1). With regard to the type of treatment, decisions that came up were about surgery, medication (starting, stopping, changing the dosage or way of administration), physiotherapy, psychological support and diet. There was no clear pattern to be able to predict how certain decisions or circumstances would influence patients’ preferences regarding involvement. For example, when comparing decisions regarding surgery with decisions regarding medication, some respondents preferred more involvement in deciding about surgery, whereas other respondents preferred more involvement regarding decisions about medicines. To provide another example, some respondents stated they preferred more involvement in deciding about changing the dosage, as opposed to deciding what medicines to take, whereas others preferred more involvement regarding the decision what medicines to take, as opposed to deciding about changing the dosage. Regarding the severity of the complaints, there were respondents who preferred more personal involvement if the severity of their complaints increased, whereas others preferred to leave treatment decisions more to their doctor in such cases.

Box 1 Common rationales regarding circumstances that may change respondents’ role preferences |

Type of treatment |

“With medication, you often know what will happen. Surgery is often much more radical to me: Then you need stop your medication, you need to be hospitalised, you just feel much worse. […] If the time comes that a surgery is necessary, then the doctor can make that decision. Not me.” [Female, 41 years] |

“Well, with medication, […] you always have something to say about it, because you do not have to take them anymore if you do not want to. But If she tells me about a surgery, […] I would say I would first like to wait a little longer and think about it. But that, to me, is of a different order than medication.” [Female, 61 years] |

“Starting [medication]. Because the medication can be quite intense, it is very important to me to think about it: Do I want this? And if you are already using medication, and your dosage needs to be increased, then… I cannot decide myself if the dosage needs to be changed or not. That is a doctor’s task.” [Female, 62 years] |

“The way of administration is more personal than increasing or decreasing the dosage. Starting to inject yourself is more personal than starting to take tablets.” [Female, 41 years] |

“When starting medication I prefer to share in the decision-making process. Increasing the dosage is something I want to decide myself, as I’m the one who can best determine how severe my pain is. And the doctor decides if the dosage needs to be decreased, because he/she understands what my blood level results mean. If I would need psychological support, I would make that decision myself. And with regards to a decision about diet, I prefer to go to a naturopath, because that is better suited to my eating habits and way of living.” [Female, 56 years] |

“I don’t have knowledge of medication, but I do have an opinion about physiotherapy.” [Female, 60 years] |

Severity of complaints |

“It also depends on how you feel. Actually. If you feel fine, you think: Say whatever you want, but I do not need it, and if you do not feel so good, then I gratefully take the advice.” [Female, 41 years] |

“When you get so many physical complaints, you start to think: action needs to be taken. But I do believe that you need to talk with your doctor about the right solution for you personally and what should be done. […] And information should also be provided about the medication, the pros and cons.” [Female, 62 years] “Last year I was in so much pain. My knees were killing me. I called the doctor and like a drug addict I begged for an injection. Normally I wait until the next check-up and the blood level results, but now I took control.” [Female, 54 years] |

Perceived involvement in MDM

When asking respondents about how they perceived their involvement in MDM so far, most respondents stated that they had experienced either shared decision-making (n = 13) or the doctor making the decision(s) (n = 15). One respondent perceived to have decided by herself. Overall, it seemed patients wanted more participation than they perceived.

Barriers in getting involved in MDM

Some patients who preferred to have a more active role in MDM perceived barriers in getting involved in the decision-making process. An overview of all identified barriers is provided in Table 1. The perceived barriers can be doctor- or patient-related but can also be contextual. Examples of doctor-related barriers perceived by patients are (a) the doctor not appearing to take the patient’s problems seriously and the patient not knowing how to respond and thus freezing; (b) the patient not being able to participate in the medical decision-making process, because of the doctor not acknowledging their role in the decision-making, to be seen from the fact that he/she does not offer alternatives or immediately rejects the patient’s questions or suggestions; (c) patients not being adequately informed (respondents stated to have received either too little, too much or too complex information).

On the patient’s side, some patients lacked awareness about treatment alternatives or the possibility to choose. Other respondents mentioned that they experienced a lack of knowledge or that they did not want to delay the treatment and therefore chose to let the doctor decide. Others stated that their lack of assertiveness hindered their participation. A few respondents mentioned that they were not yet ready to accept the diagnosis and therefore found it hard to participate in MDM. Finally, some patients mentioned that they purposively held back certain information from their doctor (about visiting another health-care professional, taking complementary or alternative medicine or about not supporting treatment). According to the patients themselves, this does not necessarily have to be a barrier for patient participation, but it may influence the collaboration and interaction between doctor and patient.

We also identified contextual barriers, such as “too little time to decide” or the study protocols, which leave little room for an informed choice. In those circumstances, respondents often felt they had no choice.

Facilitators for participation in MDM

Respondents were asked which factors facilitated or would have facilitated their participation in MDM. An overview of the facilitators identified is provided in Table 2. The results show that many facilitators for patient participation are the opposite of the reported barriers. For example, patients feel that they can more easily participate in the decision-making process when they are explicitly invited to do so, when they are taken seriously and being listened to, when the doctor is open to answering questions and when he/she explains well and offers alternative options. A good doctor-patient relationship with mutual respect, an open style of communication and trust, is often seen as a great facilitator for patient participation. Certain characteristics of the patients themselves can also make it easier to participate: If the patient is assertive and not reserved about asking questions, the patient can more easily participate in the decision-making process. Other facilitators are contextual, such as time to think things over, the availability of information to read at home and the opportunity to ask someone from the hospital or clinic questions. These contextual facilitators are important, because many patients have questions that arise after the consultation (at home), when they process all the information.

Discussion and conclusion

By understanding the patients’ motives for (not) wanting to participate in MDM and the factors that hinder or promote their participation, we can make it easier for health-care professionals to pursue the preferred level of individual patient involvement. Our findings are consistent with previous studies which also showed that many RA patients prefer SDM [3, 12, 14, 31] and that preference regarding involvement varies within and between individuals [15]. Our qualitative study revealed some interesting findings and demonstrates the complexity of factors influencing (the preference regarding) patient involvement.

Many patients participating in our study had obvious difficulties in determining their preference regarding involvement in MDM, because they had never actively considered it, had problems conceptualising patient participation or felt that they had no choice. Unawareness of having a choice is a known barrier for patient participation [22–25], and previous studies have shown that patients are more motivated for SDM after being informed about the possibilities and benefits of it [26, 34–37]. Therefore, we recommend initiatives to inform and educate patients about SDM to be more specifically aimed at increasing patients’ awareness of having a choice.

These difficulties expressed by respondents when indicating their preference for participation regarding involvement in MDM are also reflected in the ambiguous answers some respondents gave. Several studies have reported that patients have difficulties with conceptualising their role in MDM [32, 38–42], and some report that this may have to do with different interpretations of the CPS labels [38–40, 43]. These studies suggest that the CPS may conflate several concepts like the complexity of preferred patient involvement, information seeking preferences and doctor’s ability to engage in shared decision-making.

Some patients who preferred SDM were especially attracted to the notion of shared responsibility, whereas others did not agree with that. Many other studies have shown that patients want information about their medical condition and the different treatment options without necessarily having to make the final treatment decisions [3, 15, 44–50]. Our results go one step further: Although some patients preferred to share in the decision-making process or even preferred autonomous decision-making, they wanted the doctor to be responsible for the outcome of the treatment. This shows that patients may feel responsible for the decision about the treatment, because they value to be given treatment options to evaluate the impact they may have on their life, but because they do not have the medical knowledge and have to rely on the expertise of the doctor, they see the doctor as the person to be responsible for the outcome of the treatment. When involving patients in MDM, doctors will need to make explicit to the patients that participating in MDM is not a derogation of responsibility.

As with other conditions, some of our respondents preferred to leave the decision-making up to their doctor. Reasons for this preference included trusting the doctor and valuing the doctor’s expertise. This finding is consistent with those of Kraetschmer et al. [51] and Fraenkel et al. [24], who found an inverse relationship between the preference to take on an active role in decision-making and trust. They suggest that patients may fail to recognise the potential value of their own input in situations where they have complete trust in their physician. Alternatively, they suggest that patients who trust their physician may believe him/her to understand their values and to know what is best for them. We believe that patients’ preferences regarding involvement in MDM need to be respected. However, if patients prefer to leave the decision-making to their doctor, the patients’ input should still be acknowledged, the doctor closely fitting in the chosen treatment with the patients’ values and lifestyle. This patient-centred way of communication may again increase trust and adherence to the decisions made [52, 53].

Our study revealed that patients’ preferences regarding involvement in MDM may change over time, depending on the severity of the complaints and the type of decision. Previous studies have shown that preference for involvement may decrease as the severity of the complaints increases [15, 22, 23, 45, 54]. Our data, however, suggest that for some patients, increased severity of health problems actually increases the preference for involvement. With regard to the type of decision, prior studies have found that participants prefer more active roles in the decision-making process where minor illnesses, behavioural decisions, major surgeries or decisions that require medical knowledge are concerned [5]. In our study, however, we found no clear pattern of how certain types of decision affected patients’ preferences in this respect. This means that these factors are hard to use when predicting patients’ preferences regarding involvement in the decision-making process. It is necessary to further examine these complex relationships between severity of health problems and the type of treatment on the one hand and preference regarding involvement on the other. We recommend health-care professionals to assess a patient’s individual preference with every decision at stake. Person perception training [55] may enhance the professional’s accuracy in perceiving and understanding a patient’s preference in particular situations.

Although it is essential to know if patients want to participate, it is as much important to know if they can. A considerable group of patients in our study would have liked more participation than they had experienced in the past MDM. As with studies conducted for other conditions [22–25], we identified barriers in patient involvement related to the doctor, the patient and the circumstances. Doctor-related barriers mostly concern communication skills and a paternalistic attitude. Known patient-related barriers in patient involvement are a lack of knowledge, lack of awareness of having a choice and a lack of assertiveness. Our study also revealed a barrier on the patient’s side that, to our knowledge, has not been reported in previous studies about barriers in patient participation. Patients sometimes hold back information, which may, according to the patients themselves, negatively influence the doctor-patient relationship and the decision-making process. Other patients emphasised that an open style of communication and mutual respect are important facilitators for a good doctor-patient relationship. As a two-way information exchange is a prerequisite for SDM—according to the definition [47, 48]—holding back information may inhibit SDM. Another interesting barrier on the patients’ side is patients not wanting to delay the treatment and thus letting the doctor decide. Salt and Peden [56] reported that desperation or hope for the relief of symptoms was the foundation for deciding to take medications for RA, but it has not previously been reported as a barrier for patient participation. In sum, many barriers are related to communication on both the doctor’s and the patient’s side.

These communication-related barriers may be overcome with education and support of both doctors and patients. According to a recent report, more than 50 SDM-training programmes for health-care professionals have been developed worldwide, varying in learning objectives, duration and teaching materials [57]. For practical reasons, most programmes are accessible to doctors only, and the effectiveness of such programmes has not yet been properly assessed [57, 58].

With regard to the education of patients, patient decision aids (PtDAs) that offer balanced and reliable information about all treatment options and that help patients examine their personal values, worries, doubts and questions regarding these treatment options may be helpful [59]. Integrating PtDAs in the health-care system may raise awareness for patient participation in MDM and could help educate patients about asking the right questions and doctors about offering more than one option and recognising the patient’s role in MDM. However, according to a recent systematic review providing knowledge to patients and encouraging them to think about personal values is not enough. The authors concluded that, to participate in SDM, patients need knowledge (about treatment options available and of personal preferences and goals) and power (i.e. the believed ability to use this knowledge to influence decision-making in the encounter with the doctor) [25]. Education should therefore also be focused on changing attitudes of both doctors and patients to overcome the power imbalance between doctors and patients in medical decision-making.

There are some limitations to this study that need to be considered. Firstly, the participants in this study were recruited from two hospitals. Although these hospitals are large hospitals covering both urban and rural areas, this might limit the generalisability of the results. However, we have no reason to believe that patients from the eastern parts of The Netherlands, where this study was conducted, think differently about participation in MDM than patients from other Dutch regions. Future quantitative studies are needed to replicate and expand our results. Secondly, although we tried to prevent selection bias by preselecting patients diagnosed with RA before they consulted their rheumatologist, we cannot guarantee that it did not occur. Thirdly, this was a retrospective study in which patients were asked to reflect on a recent medical decision, but sometimes that decision occurred weeks or months prior to the interview. However, what is potentially lost by these limitations was gained by allowing respondents to tell their own story.

Despite these limitations, our findings provide important practical information and recommendations for future research. It seems that recent attempts from the Dutch government to improve patient-centred care and SDM [60] (e.g. by developing PtDA’s and quality indicators) have not yet been successful. We believe that the physician can have an important role as facilitator in enhancing patient participation in MDM, but implementing SDM is a shared responsibility; all parties need to be involved and educated. Physicians need to be aware of the fact that preferences regarding participation may vary both between and within individuals. They need to mention and explain all treatment options available and invite patients explicitly to participate in every treatment decision. Even if there is only one possible treatment option available, patients still have a choice—that is, to initiate or not—and they need to be asked about their opinion, worries, doubts or questions. With regard to the patient, more initiatives need to be taken that are directly aimed at patients to make them aware of the possibility to participate in MDM and of the potential value of their input [25]. To support shared decision-making, the development and implementation of PtDA’s using a holistic approach, which encounters the needs of all stakeholders (patients and health professionals) and the integration in the health-care system, can be of great value. For future research, we recommend a quantitative and longitudinal study to show how patients’ preferences regarding participation in rheumatology care may change over time—the patient during this time establishing a long-term relationship with the health-care professionals—and how these preferences are related to the type of treatment and the severity of the complaints.

References

Brosseau L, Lineker S, Bell M, Wells G, Casimiro L, Egan M et al (2012) People getting a grip on arthritis: a knowledge transfer strategy to empower patients with rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis. Health Educ J 71(3):255–267. doi:10.1177/0017896910387317

Kiesler DJ, Auerbach SM (2006) Optimal matches of patient preferences for information, decision-making and interpersonal behavior: evidence, models and interventions. Patient Educ Couns 61(3):319–341. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2005.08.002

Neame R, Hammond A, Deighton C (2005) Need for information and for involvement in decision making among patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a questionnaire survey. Arthrit Care Res 53(2):249–255

O’Connor AM, Stacey D, Légaré F, Santesso N (2004) Knowledge translation for patients: methods to support patients participation in decision making about preference sensitive treatment options in rheumatology. In: Tugwell P, Shea B, Boers M, Brooks P, Simon LS, Strand V et al (eds) Evidence-based rheumatology. BMJ Publishing Group, London

Say R, Murtagh M, Thomson R (2006) Patients’ preference for involvement in medical decision making: a narrative review. Patient Educ Couns 60(2):102–114. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2005.02.003

Whitney SN, Holmes-Rovner M, Brody H, Schneider C, McCullough LB, Volk RJ et al (2008) Beyond shared decision making: an expanded typology of medical decisions. Med Decis Making 28(5):699–705. doi:10.1177/0272989x08318465

Kassirer JP (1994) Incorporating patients’ preferences into medical decisions. N Engl J Med 330(26):1895–1896

Kjeken I, Dagfinrud H, Mowinckel P, Uhlig T, Kvien TK, Finset A (2006) Rheumatology care: involvement in medical decisions, received information, satisfaction with care, and unmet health care needs in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis. Arthrit Care Res 55(3):394–401

Ward MM, Sundaramurthy S, Lotstein D, Bush TM, Neuwelt CM, Street RL (2003) Participatory patient–physician communication and morbidity in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthrit Care Res 49(6):810–818. doi:10.1002/art.11467

Coulter A (1997) Partnerships with patients: the pros and cons of shared clinical decision-making. J Health Serv Res Policy 2(2):112–121

Little P, Everitt H, Williamson I, Warner G, Moore M, Gould C et al (2001) Observational study of effect of patient centredness and positive approach on outcomes of general practice consultations. BMJ 323(7318):908–911. doi:10.1136/bmj.323.7318.908

Schildmann J, Grunke M, Kalden JR, Vollmann J (2008) Information and participation in decision-making about treatment: a qualitative study of the perceptions and preferences of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Med Ethics 34(11):775–779. doi:10.1136/jme.2007.023705

Strull WM, Lo B, Charles G (1984) Do patients want to participate in medical decision making? JAMA 252(21):2990–2994. doi:10.1001/jama.1984.03350210038026

Deber RB, Kraetschmer N, Urowitz S, Sharpe N (2007) Do people want to be autonomous patients? Preferred roles in treatment decision-making in several patient populations. Health Expect 10(3):248–258

Levinson W (2005) Not all patients want to participate in decision making. A national study of public preferences. J Gen Intern Med 20(6):531–535

Deber RB, Kraetschmer N, Irvine J (1996) What role do patients wish to play in treatment decision making? Arch Intern Med 156(13):1414–1420. doi:10.1001/archinte.1996.00440120070006

Funk LM (2004) Who wants to be involved? Decision-making preferences among residents of long-term care facilities. Can J Aging 23(1):47–58

Janz NK, Wren PA, Copeland LA, Lowery JC, Goldfarb SL, Wilkins EG (2004) Patient-physician concordance: preferences, perceptions, and factors influencing the breast cancer surgical decision. J Clin Oncol 22(15):3091–3098. doi:10.1200/jco.2004.09.069

Murray E, Pollack L, White M, Lo B (2006) Clinical decision-making: patients’ preferences and experiences. Patient Educ Couns 65(2):189–196

Pieterse AH, Baas-Thijssen MCM, Marijnen CAM, Stiggelbout AM (2008) Clinician and cancer patient views on patient participation in treatment decision-making: a quantitative and qualitative exploration. Br J Cancer 99(6):875–882

Vogel BA, Bengel J, Helmes AW (2008) Information and decision making: patients’ needs and experiences in the course of breast cancer treatment. Patient Educ Couns 71(1):79–85

Caress AL, Beaver K, Luker K, Campbell M, Woodcock A (2005) Involvement in treatment decisions: what do adults with asthma want and what do they get? Results of a cross sectional survey. Thorax 60(3):199–205. doi:10.1136/thx.2004.029041

Fraenkel L, McGraw S (2007) Participation in medical decision making: the patients perspective. Med Decis Making 27:533–538. doi:10.1177/0272989x07306784

Fraenkel L, McGraw S (2007) What are the essential elements to enable patient participation in medical decision making? J Gen Intern Med 22(5):614–619. doi:10.1007/s11606-007-0149-9

Joseph-Williams N, Elwyn G, Edwards A (2014) Knowledge is not power for patients: a systematic review and thematic synthesis of patient-reported barriers and facilitators to shared decision making. Patient Educ Couns 94(3):291–309. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2013.10.031

Politi MC, Dizon DS, Frosch DL, Kuzemchak MD, Stiggelbout AM (2013) Importance of clarifying patients’ desired role in shared decision making to match their level of engagement with their preferences. BMJ. 347:f7066. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24297974

Chewning B, Bylund CL, Shah B, Arora NK, Gueguen JA, Makoul G (2012) Patient preferences for shared decisions: a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns 86(1):9–18. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2011.02.004

Dillard AJ, Couper MP, Zikmund-Fisher BJ (2010) Perceived risk of cancer and patient reports of participation in decisions about screening: The DECISIONS Study. Med Decis Making 30(5 suppl):96S–105S. doi:10.1177/0272989x10377660

Vogel BA, Helmes AW, Hasenburg A (2008) Concordance between patients’ desired and actual decision-making roles in breast cancer care. Psycho-Oncology 17(2):182–189

Joosten EAG, DeFuentes-Merillas L, de Weert GH, Sensky T, van der Staak CPF, de Jong CAJ (2008) Systematic review of the effects of shared decision-making on patient satisfaction, treatment adherence and health status. Psychother Psychosom 77(4):219–226

Garfield S, Smith F, Francis SA, Chalmers C (2007) Can patients’ preferences for involvement in decision-making regarding the use of medicines be predicted? Patient Educ Couns 66(3):361–367

Degner LF, Kristjanson LJ, Bowman D, Sloan JA, Carriere KC, O’Neil J et al (1997) Information needs and decisional preferences in women with breast cancer. JAMA 277(18):1485–1492. doi:10.1001/jama.1997.03540420081039

Patton M (2002) Qualitative research and evaluation methods. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Inc.

Sainio C, Lauri S, Eriksson E (2001) Cancer patients’ views and experiences of participation in care and decision making. Nurs Ethics 8(2):X-113

Henderson S (2002) Influences on patient participation and decision-making in care. Professional Nurse (Lond Engl) 17(9):521–525

Belcher VN, Fried TR, Agostini JV, Tinetti ME (2006) Views of older adults on patient participation in medication-related decision making. J Gen Intern Med 21(4):298–303

Entwistle V, Prior M, Skea ZC, Francis JJ (2008) Involvement in treatment decision-making: its meaning to people with diabetes and implications for conceptualisation. Soc Sci Med 66(2):362–375

Entwistle VA, Skea ZC, O’Donnell MT (2001) Decisions about treatment: interpretations of two measures of control by women having a hysterectomy. Soc Sci Med 53(6):721–732

Davey HM, Lim J, Butow PN, Barratt AL, Redman S (2004) Women’s preferences for and views on decision-making for diagnostic tests. Soc Sci Med 58(9):1699–1707. doi:10.1016/s0277-9536(03)00339-3

Henrikson NB, Davison BJ, Berry DL (2011) Measuring decisional control preferences in men newly diagnosed with prostate cancer. J Psychosoc Oncol 29(6):606–618. doi:10.1080/07347332.2011.615383

Degner LF, Sloan JA (1992) Decision making during serious illness: what role do patients really want to play? J Clin Epidemiol 45(9):941–950

Alderson P, Madden M, Oakley A, Wilkins R, Lee J (1994) Women’s views of breast cancer treatment and research. http://research.ioe.ac.uk/portal/en/publications/womens-views-of-breast-cancer-treatment-andresearch%280c74a31a-aa38-4c34-a901-6f5109525d82%29/export.html

Gattellari M, Ward JE (2005) Measuring men’s preferences for involvement in medical care: getting the question right. J Eval Clin Pract 11(3):237–246. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2753.2005.00530.x

Arora NK, McHorney CA (2000) Patient preferences for medical decision making: who really wants to participate? Med Care 38(3):335–341

Ende J, Kazis L, Ash A, Moskowitz M (1989) Measuring patients’ desire for autonomy. J Gen Intern Med 4(1):23–30

Beisecker AE, Beisecker TD (1990) Patient information-seeking behaviors when communicating with doctors. Med Care 28(1):19–28

Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T (1997) Shared decision-making in the medical encounter: what does it mean?(or it takes at least two to tango). Soc Sci Med 44(5):681–692

Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T (1999) Decision-making in the physician–patient encounter: revisiting the shared treatment decision-making model. Soc Sci Med 49(5):651–661. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(99)00145-8

Edwards A, Elwyn G (2006) Inside the black box of shared decision making: distinguishing between the process of involvement and who makes the decision. Health Expect 9(4):307–320. doi:10.1111/j.1369-7625.2006.00401.x

Bhavnani V, Fisher B (2010) Patient factors in the implementation of decision aids in general practice: a qualitative study. Health Expect 13(1):45–54

Kraetschmer N, Sharpe N, Urowitz S, Deber RB (2004) How does trust affect patient preferences for participation in decision‐making? Health Expect 7(4):317–326

Berrios-rivera JP, Street RL, Garcia Popa-lisseanu MG, Kallen MA, Richardson MN, Janssen NM et al (2006) Trust in physicians and elements of the medical interaction in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthrit Care Res 55(3):385–393. doi:10.1002/art.21988

Keating NL, Gandhi TK, Orav EJ, Bates DW, Ayanian JZ (2004) Patient characteristics and experiences associated with trust in specialist physicians. Arch Intern Med 164(9):1015

Tariman J, Berry D, Cochrane B, Doorenbos A, Schepp K (2010) Preferred and actual participation roles during health care decision making in persons with cancer: a systematic review. Ann Oncol 21(6):1145–1151

Blanch-Hartigan D, Ruben MA (2013) Training clinicians to accurately perceive their patients: current state and future directions. Patient Educ Couns 92(3):328–336. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2013.02.010

Salt E, Peden A (2011) The complexity of the treatment: the decision-making process among women with rheumatoid arthritis. Qual Health Res 21(2):214–222

Legare F, Politi MC, Drolet R, Desroches S, Stacey D, Bekker H (2012) Training health professionals in shared decision-making: an international environmental scan. Patient Educ Couns 88(2):159–169. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2012.01.002

Koerner M, Wirtz M, Michaelis M, Ehrhardt H, Steger A-K, Zerpies E et al (2014) A multicentre cluster-randomized controlled study to evaluate a train-the-trainer programme for implementing internal and external participation in medical rehabilitation. Clin Rehabil 28(1):20–35. doi:10.1177/0269215513494874

Stacey D, Légaré F, Col NF, Bennett CL, Barry MJ, Eden KB et al (2014) Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Status and date: Edited (no change to conclusions), published in. (1)

Ministerie van Volksgezondheid We S (2011) Landelijke nota gezondheidsbeleid: Gezondheid dichtbij. In: Ministerie van Volksgezondheid WeS, editor. Den Haag

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the rheumatologists for recruiting the patients and respondents for participating in this study. This study was financially supported by the Dutch Arthritis Foundation.

Ethical standards

The study did not need approval of the ethical review board according to the Dutch Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act (WMO); only (non-intervention) studies with a high burden for patients have to be reviewed. All persons gave their informed consent prior to their inclusion in the study. The authors confirm that all patient/personal identifiers have been removed or disguised, so the person(s) described are not identifiable and cannot be identified through the details of the story.

Financial supporter

The Dutch Arthritis Association.

Conflict of interest

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nota, I., Drossaert, C.H.C., Taal, E. et al. Arthritis patients’ motives for (not) wanting to be involved in medical decision-making and the factors that hinder or promote patient involvement. Clin Rheumatol 35, 1225–1235 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-014-2820-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-014-2820-y