Abstract

LupusPRO is a disease-targeted patient-reported outcome measure that was developed and validated from and among US patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). We herein report the results of the cross-cultural adaptation and validation study of the Turkish translated version of the LupusPRO. Turkish LupusPRO and the Medical Outcomes Study Short Form (SF-36) (Turkish) were administered to the Turkish lupus patients. Disease activity was ascertained using the physician global assessment (PGA), Safety of Estrogens in Lupus Erythematosus National Assessment–Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index (SELENA-SLEDAI), and flare (defined by LFA—Lupus Foundation of America). Disease damage was assessed with Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics/American College of Rheumatology damage index (SDI). Also, second Turkish LupusPRO tests were given to the patients to be completed within 2–3 days and sent back to us. Internal consistency reliability, test–retest reliability, and convergent and criterion validity (against disease activity or health status) were tested. All reported p values are two-tailed. The conceptual framework of the LupusPRO was evaluated using confirmatory factor analysis appropriate for categorical data. One hundred two SLE subjects (94 % women) were enrolled. The median (IQR) age and mean disease duration (±SD) were 38.5 (18) years and 60.3 (±56.3) months, respectively. The mean ± SD, SLEDAI, and SDI scores were 3.1 ± 3.7 and 0.52 ± 0.75, respectively. There were 25 patients who had flares at the time of study. Forty-two patients with no change in their health status completed and sent back the second LupusPRO test and were included in the test–retest analysis. Test–retest reliability of LupusPRO domains ranged from 0.87 to 0.97, while internal consistency reliability of the domains ranged from 0.63 to 0.94. Convergent validity with corresponding domains of SF-36 was present. Health-related quality-of-life domains performed well against disease activity measures (PGA, total SLEDAI, LFA flare, and SF-6D—overall health status), establishing its criterion validity. Item-to-factor loadings representing the hypothesized item-to-scale relationships were satisfactory. The model fit for the hypothesized item-to-scale relationships was also satisfactory. The Turkish version of the LupusPRO is valid and appears to perform comparably to the English and Spanish language versions. It can be used as a patient-reported outcome parameter in clinical trials, as well as longitudinal studies for testing responsiveness to change.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is an autoimmune disease with a significant impact on physical, social, and psychological health. Currently, disease activity or damage indices composed of laboratory, radiological, or clinical findings emphasizing physicians’ assessments are mostly used in clinical care and research to evaluate health outcomes. However, these have been found to be poorly correlated not only with patient assessments of disease activity [1] but also with quality of life [2] in patients with lupus. In fact, the patient is the best source for assessing the effects of the disease or its treatment on daily life. Therefore, patient-reported outcomes (PRO), used in conjunction with physician assessments of disease activity and damage, are the preferred assessment methods both for patient care and research. Moreover, the use of a patient-reported outcome measure (PROM) as a core outcome measure for SLE is highly encouraged, and the Food and Drug Administration requires its use in clinical trials, especially for licensing and promoting new medications [3].

LupusPRO is a disease-targeted patient-reported outcome measure that was developed and validated from and among US patients with SLE [4]. The LupusPRO includes a comprehensive assessment (health and non-health) with quality of life and pertinent SLE domains that are not yet available in other SLE-specific patient-reported outcome measures. Its Spanish version has also been recently validated [5]. None of the validated disease-specific PROM is currently available in Turkish. Therefore, we aimed to cross-culturally adapt an existent disease-specific PRO tool for use in Turkish SLE patients. We herein report the results of the cross-cultural validation study of the translated version of the LupusPRO in Turkish SLE patients.

Methods

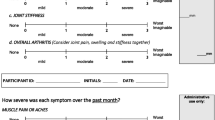

LupusPRO has two constructs: health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and non-health-related quality of life (Non-HRQoL). HRQoL domains are (1) lupus symptoms, (2) lupus medications (3) physical health [themes: physical function and role physical], (4) emotional health [themes: emotional function and role emotional], (5) pain/vitality [themes: fatigue, sleep], and (6) procreation [themes: sexual health and reproduction], (7) cognition, and (8) body image. Non-HRQoL domains are (1) desires/goals, (2) coping, (3) relationship/social support, and (4) satisfaction with care. Individual domain scores, total HRQoL, and total non-HRQoL scores range from 0 to 100, where higher scores indicate better health.

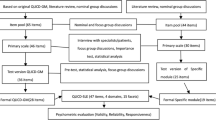

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Gazi University Medical Faculty. Forward and backward translations of the 43-item English LupusPRO were undertaken using standard guidelines [6], to develop the Turkish LupusPRO. The tool was pretested in five individuals and finalized based on their feedback.

Adult patients (≥18 years old) meeting the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) classification criteria for SLE [7] were eligible for enrollment if they were able to read and understand Turkish. The finalized Turkish version was applied to consenting Turkish-speaking SLE patients. Data on the following variables were collected at baseline visit (T1): Demographic information, clinical and serological characteristics, disease activity, and damage assessment. In addition, the Turkish LupusPRO (T1), the Turkish version of the Medical Outcomes Study Short Form (SF-36) [8], was self-administered to all participating patients at that time. Higher scores on SF-36 denote better health. For test–retest validity assessment, a second copy of Turkish LupusPRO questionnaire was provided to the patients to be completed within 2–3 days of T1 (T2) to be mailed or dropped back in person to the study site.

Disease activity was evaluated using physician global assessment (PGA), a modified version of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index (SLEDAI) that was developed for the Safety of Estrogens in Lupus Erythematosus National Assessment (SELENA) trial (SELENA-SLEDAI) [9] and the Lupus Foundation of America (LFA)-defined Flare (Yes/No) [10]. Cumulative damage from either the disease or therapies used for it was assessed using the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics/American College of Rheumatology (SLICC/ACR) damage index (SDI) [11]. ‘SF-6D’ is another parameter which reflects overall health status and was also applied to assess disease activitiy. The SF-6D has been developed subsequent to the introduction of the SF-36 and provides a method to transform responses from select items of SF-36 domains into an index based SF-6D measure that contains six domains [12].

Psychometric properties studied included the following: internal consistency and reliability for each domain were evaluated using Cronbach’s alpha, where an alpha >0.70 is considered acceptable [13]. Test–retest reliability was tested by evaluating the agreement between the patient responses to each domain at two time points. Convergent validity was evaluated based on the strength of correlation of LupusPRO with related domains on SF-36 using Spearman’s correlation coefficient. Criterion validity of the LupusPRO was judged based on its correlation with either health status, measures of disease activity, or damage. Correlations were classified as strong (r > 0.5), moderate (0.3 ≤ r < 0.5), weak (0.1 ≤ r < 0.3), or absent (r < 0.1). The tool was considered responsive if changes in its domain or summary scores correlated with changes in health status and/or disease activity and in the expected direction. The conceptual framework (hypothesized item to scale relationships) of the LupusPRO was evaluated using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) appropriate for categorical data. CFA was conducted with the LupusPRO item responses using a robust weighted least squares estimator and the software Mplus [14]. Mplus employs a multi-step method for ordinal outcome variables that analyzes a matrix of polychoric correlations rather than covariances. The goodness of fit of the hypothesized item-to-scale relationships (multi-factor) was evaluated with the comparative fit index (CFI) and Tucker–Lewis index (TLI). CFI and TLI are comparative fit indices, which quantify the amount of difference between the examined model and the independence model (i.e., a standard comparison model that asserts none of the components in the model is related), with higher scores indicating larger differences. It is recommended that these two indices be 0.9 or greater as evidence of acceptable model fit [15]. All reported p values are two-tailed, and a p value <0.5 is taken significant.

Results

One hundred two patients with SLE (94 % women) were enrolled in this study. All patients have been followed at the Gazi University Medical Faculty, Department of Internal Medicine, Rheumatology outpatient clinic. The median (IQR; min. to max.) age and mean disease duration (±SD) were 38.5 (18; 18 to 67) years and 60.3 (±56.3) months, respectively. Forty-four percent had less than high school education, and 78.4 % were currently married. Of the 102 patients, 99 (97.1 %) had cutaneous manifestations, 8 (7.8 %) had history of serositis, 27 (26.5 %) had lupus nephritis, 11 (10.8 %) had neuropsychiatric manifestations, 25 (24.5 %) had hematological manifestations, 54 (52.9 %) had musculoskeletal manifestations, and 11 (10.8 %) had thrombo-embolic manifestations. Rates of these manifestations are cumulative occurances for the entire disease duration. The mean ± SD, SELENA-SLEDAI, and SDI were 3.1 ± 3.7 and 0.52 ± 0.75. There were 25 patients with LFA-defined flare status (11 patients had mild, 8 patients had moderate, and 6 patients had severe flare) at the baseline visit (Table 1). PGA scores were 0 for 26 %, 1 for 60 %, 2 for 11 %, and 3 for 5 % of patients. Forty-five percent of patients were taking prednisone, 87 % hydroxychloroquine, 16 % azathioprine, and 6 % mycophenolate mophetil at the time of the study.

Mean scores on the LupusPRO domains are shown in Table 2. Our patients scored poorly especially in the emotional health and social support domains. Internal consistency reliability (ICR) of the domains ranged from 0.63 to 0.94. The alpha values of ICR tests were over 0.70 for all domains except lupus symptoms domain. Test–retest reliability of the LupusPRO domains ranged from 0.87 to 0.98 (Table 2).

Convergent validity of LupusPRO was confirmed using the corresponding domains of SF-36. As expected, the physical health domain of LupusPRO had good correlations with physical functions (r = 0.65, p = 0.001) and role physical (r = 0.64, p = 0.001) domains of SF-36. Similarly, the emotional health domain of LupusPRO correlated well with mental health (r = 0.52, p = 0.001) and role emotional (r = 0.53, p = 0.001) domains of SF-36. The pain/vitality domain of LupusPRO correlated well, as expected, with the vitality (r = 0.79, p = 0.0001) and bodily pain (r = 0.68, p = 0.001) domains of SF-36 (Table 3).

Criterion validity of the HRQOL domains of the LupusPRO was also demonstrated against disease activity measures (PGA, SELENA-SLEDAI, LFA flare, and SF-6D) (Table 3). Significant correlations between patient-reported change in health (since last visit) with cross-sectional domain scores in the anticipated directions were noted in the majority of domains, including lupus symptoms, cognition, physical health, pain/vitality, desires/goals. PGA correlated well with all the parameters tested, except cognition. Statistically significant correlation between SELENA-SLEDAI scores and LupusPRO was found at physical health domain only (r = −0.27, p = 0.006). LFA flare had significant correlation only with emotional health domain of LupusPRO (r = −023, p = 0.02). Interestingly, the best correlations were observed between SF-6D and LupusPRO domains. There were significant correlations between SF-6D with all of LupusPRO domains, except desires/goals domain, which also correlated well but had borderline statistical significance (r = 0.42, p = 0.05).

Results of confirmatory factor analysis lend empirical support for the conceptual framework of the LupusPRO (Table 4). The model fit for the hypothesized item-to-scale relationships was satisfactory (CFI = 0.97, TLI = 0.98). In addition, item-to-factor loadings representing the hypothesized item-to-scale relationships were also satisfactory. In general, items loaded >0.6 with their respective factors.

Discussion

SLE itself or its treatments may profoundly affect the physical, as well as the mental, social, psychological, and sexual well-being aspects of a person’s life. Thus far, patient-reported outcomes in lupus have usually been assessed in longitudinal studies and in some clinical trials using a generic QoL tool [16, 17]. Short Form 20 was found to perform better than Health Assessment Questionnaire [18]; however with the availability of the SF-36 and its Vitality domain, the latter was preferably used in lupus studies. Responsiveness of SF-36 to changes in disease status is controversial. Some studies have reported responsiveness; however, others have revealed it is either not responsive or changes observed are not related to lupus but non-lupus manifestations, such as fibromyalgia [17, 19, 20].

Development of disease-specific or targeted QoL measures is a relatively new effort in lupus and is needed to fill in the gaps in the generic patient-reported health outcome measures [21–23]. During the validation of the LupusQoL in the US, patients noted that some important issues were not captured by LupusQoL, e.g., side effects of lupus drugs, memory and concentration, concerns for pregnancy, effect on vocational aspirations/finances, social supports available, medical care, etc. Furthermore, LupusQoL was derived from female patients with SLE. LupusPRO, a lupus-specific patient-reported outcome measure, was therefore developed from an ethnically heterogenous group of the US SLE patients of both genders (4) with the intent of capturing all pertinent issues affecting their quality of life from their own perspectives. It has fair psychometric properties, and preliminary studies indicate responsiveness to change [24].

The Turkish version of LupusPRO was cross-culturally adapted and validated. The study has included culturally diverse Turkish SLE patients from Ankara (the capital city of Turkey) and surrounding area, attending rheumatology outpatient clinic. LupusPRO exhibited fair reliability and validity. Significant correlations between patient-reported changes in health status since last visit with cross-sectional domain scores were also noted. Confirmatory factor analysis supported the hypothesized item-to-scale structure as the original LupusPRO and had an excellent fit.

The lack of longitudinal data to assess its responsiveness and minimally important difference of the different domains of the LupusPRO is certainly a limitation of our study. Disease activity scores of the study patients were lower than the patients in the US and Spanish validation studies.

Finally, the instrument may need local adaptations before its widespread use in Turkey. Strengths of the study include participation of multicultural Turkish-speaking SLE patients, as well as the inclusion of the LFA definition of flare. Although it was not part of the study methods, spontanous feedback about the LupusPRO questionnaire from the SLE patients in this study has revealed that lupus patients have difficulty differentiating lupus-related and non-lupus-related nature of their symtoms and problems they experience, suggesting that they are in great need of more information about their disease and medications.

In conclusion, the Turkish version of the LupusPRO is valid and appears to perform comparably to the English and Spanish language versions. It can be used as a patient-reported outcome parameter in clinical trials, as well as longitudinal studies for testing responsiveness to change. Using a cross-culturally adapted and validated patient-reported outcome measure might facilitate homogeneity in the methodology of multicultural lupus studies, as well as provide insight into cultural/geographic differences in health outcomes. Moreover, the LupusPRO may provide unique information to understand the feelings of SLE patients and total impact of the disease on their lives.

References

Alarcón GS, McGwin G Jr, Brooks K et al (2002) Systemic lupus erythematosus in three ethnic groups. XI. Sources of discrepancy in perception of disease activity: a comparison of physician and patient visual analog scale scoresb. Arthritis Rheum 47(4):408–413

Jolly M, Utset TO (2004) Can disease specific measures for systemic lupus erythematosus predict patients health related quality of life? Lupus 13(12):924–926

FDA Guidance on Patient Reported Outcomes. [http://www.fda.gov/cder/guidance/index htm 2006]. Accessed 29 Jul 2013

Jolly M, Pickard AS, Block JA et al (2012) Disease-specific patient reported outcome tools for systemic lupus erythematosus. Semin Arthritis Rheum 42(1):56–65

Jolly M, Block JA, Mikolaitis RA et al (2011) Spanish LupusPRO: Cross Cultural Validation Study for Lupus. Arthritis Rheum 63(10s):S725

Guillemin F, Bombardier C, Beaton D (1993) Cross-cultural adaptation of health-related quality of life measures: literature review and proposed guidelines. J Clin Epidemiol 46(12):1417–1432

Hochberg MC (1997) Updating the American College of Rheumatology revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 40(9):1725

Ware JE (1996) The SF-36 Health Survey. In: Spiker B (ed) Quality of life and pharmacoeconomics in clinical trials, 2nd edn. Lippincott-Raven, Philadelphia, pp 337–345

Petri M, Kim MY, Kalunian KC et al (2005) Combined oral contraceptives in women with systemic lupus erythematosus. N Engl J Med 353(24):2550–2558

Ruperto N, Hanrahan LM, Alarcon GS et al (2011) International consensus for a definition of disease flare in lupus. Lupus 20(5):453–462

Gladman D, Ginzler E, Goldsmith C et al (1996) The development and initial validation of the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics/American College of Rheumatology damage index for systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 39(3):363–369

Brazier J, Roberts J, Deverill M (2002) The estimation of a preference-based measure of health from the SF-36. J Health Econ 21(2):271–292

Hays RD, Anderson R, Revicki D (1993) Psychometric considerations in evaluating health-related quality of life measures. Qual Life Res 2:441–449

Mplus User’s Guide [computer program]. Version 1. Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén; 1998.

Hu L, Bentler PM (1999) Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural equation Modeling 6:1–55

McElhone K, Abbott J, Teh SL (2006) A review of health related quality of life in systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus 15:633–643

Furie R, Petri M, Zamani O et al (2011) A phase III, randomized, placebo-controlled study of belimumab, a monoclonal antibody that inhibits B lymphocyte stimulator, in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 63(12):3918–3930

Fries JF, Spitz P, Kraines RG, Holman HR (1980) Measurement of patient outcome in arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 23(2):137–145

Strand V, Chu AD (2011) Measuring outcomes in systemic lupus erythematosus clinical trials. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res 11(4):455–468

Kuriya B, Gladman DD, Ibanez D, Urowitz MB (2008) Quality of Life over time in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 59(2):181–185

Leong KP, Kong KO, Thong BY et al (2005) Development and preliminary validation of a systemic lupus erythematosus-specific quality-of-life instrument (SLEQOL). Rheumatology 44(10):1267–1276

McElhone K, Abbott J, Shelmerdine J et al (2007) Development and validation of a disease-specific health-related quality of life measure, the LupusQol, for adults with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 57(6):972–979

Doward LC, McKenna SP, Whalley D et al (2009) The development of the L-QoL: a quality-of-life instrument specific to systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Rheum Dis 68(2):196–200

Jolly M, Cornejo J, Mikolaitis RA, Block JA (2011) LupusPRO and responsiveness the changes in health status and disease activity over time. Arthritis Rheum 63(10s):S898

Disclosures

Dr. Meenakshi Jolly has financial disclosure with LFA (Lupus Foundation of America), GlaxoSmithKline, and MedImmune. Other authors declare no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kaya, A., Goker, B., Cura, E.S. et al. Turkish lupusPRO: cross-cultural validation study for lupus. Clin Rheumatol 33, 1079–1084 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-013-2345-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-013-2345-9