Abstract

Background

NICE (National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence) in England recommended laparoscopic repair for recurrent and bilateral groin hernias in 2004. The aims of this survey were to evaluate the current practise of bilateral and recurrent inguinal hernia surgery in Scotland and surgeons’ views on the perceived need for training in laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair (LIHR).

Methods

A postal questionnaire was sent to Scottish consultant surgeons included in the Scottish Audit of Surgical Audit database 2007, asking about their current practice of primary, recurrent and bilateral inguinal hernia surgery. A response was considered valid if the surgeon performed groin hernia surgery; further analysis was based on this group. Those who did not offer LIHR were asked to comment on the possible reasons, and also the perceived need for training in laparoscopic hernia surgery. Only valid responses were stored on Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation, USA) and analysed with SPSS software version 13.0 (SPSS, Chicago, Illinois).

Results

Postal questionnaires were sent to 301 surgeons and the overall all response rate was 174/301 (57.8%). A valid response was received from 124 of 174 (71.2%) surgeons and analysed further. Open Lichtenstein’s repair seems to be the most common inguinal hernia repair. Laparoscopic surgery was not performed for 26.6 and 31.5% of recurrent and bilateral inguinal hernia, respectively. About 15% of surgeons replied that an LIHR service was not available in their base hospital. Lack of training, financial constraints, and insufficient evidence were thought to be the main reasons for low uptake of LIHR. About 80% of respondents wished to attend hands-on training in hernia surgery.

Conclusions

Current practice by Scottish surgeons showed that one in three surgeons did not offer LIHR for bilateral and recurrent inguinal hernia as recommended by NICE. There is a clear need for training in LIHR.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Inguinal hernia repair is one of the most commonly performed elective operations in the UK, with around 70,000 being undertaken each year in England [1, 2] and more than 6,000/year performed in Scotland [3]. Furthermore, a recent study also reported that in Scotland only 8.9% of inguinal hernia repairs were performed laparoscopically compared to 13.5% in England. A recent survey in Wales demonstrated that only 15% of hernia repairs were being performed laparoscopically [2]. Open tension-free mesh repair seems to be the treatment of choice for inguinal hernia [4]. The surgical approaches adopted for inguinal hernia repair is currently inconsistent across the UK, with differences in the use of the open or laparoscopic approaches varying particularly widely [3,5]. Nevertheless, meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials and Cochrane reviews have clearly established the benefits of Laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair (LIHR) over the open method [6–9].

The National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE) recommends laparoscopic repair as the preferred method of treatment for bilateral or recurrent hernia. Furthermore, in 2004, NICE [1] recommended that the laparoscopic approach should also be a choice in the treatment of unilateral inguinal hernia. Besides this, in unilateral hernia and doubtful/occult contra-lateral hernia, laparoscopy offers advantages over open approaches as there is no need for additional incision and associated morbidity. The second appraisal of the NICE review in 2007 demonstrated an increase in the uptake of laparoscopic hernia surgery up to 14%; however, only a fifth of bilateral hernias in England were repaired by LIHR [1]. Likewise, 22% of bilateral primary hernias were repaired laparoscopically in Scotland [3].

The aim of this survey was to evaluate the current practice of LIHR by Scottish surgeons and to explore the reasons for its low uptake.

Method

A postal questionnaire was sent to 301 consultant surgeons in Scotland. The postal addresses were obtained from Scottish Audit of Surgical Audit database 2007. The questionnaire asked for information about the consultant surgeons’ regular base hospital and their surgical practice in the following clinical situations: bilateral hernia; recurrent hernia after an open repair; and recurrent hernia after laparoscopic repair. The questionnaire also asked surgeons to indicate the reasons why LIHR was not being adopted more widely. Furthermore, the need for LIHR training for consultants was surveyed. The responses were classified as valid if the consultants admitted to performing hernia surgery. Non-valid responses included surgeons who no longer perform hernia surgery or addressees that could not be found. Only valid responses were analysed.

Data from the returned questionnaires were tabulated and analysed using SPSS version 13.0 (Statistical Package for Social Sciences, Chicago, Illinois).

Results

We received a total of 174 responses out of 301 questionnaires (response rate 57.8%), of which 124 were valid responses, i.e. surgeons who performed inguinal hernia repair surgery (124/174, 71.3%), and 50 were not valid. The majority of respondents were above 50 years of age (63/124, 50.8%), followed by 49/124 (39.5%) aged 40–49, and 11/124 (8.9%) aged 30–39.

We received completed surveys from surgeons representing all Scottish health boards. Most of the respondents were surgeons from Glasgow (22.6%), followed by Tayside, Highland, Lanarkshire (9.7%), and Lothian (8.9%). Responses were recorded from all other health boards including Grampian, Ayrshire and Arran, Fife, Forth Valley, Dumfries and Galloway, the Borders, the Western Isles, Orkney, and Shetland. A total of 105 respondents (84.7%) replied that their base hospitals had surgeons who did perform LIHR; 19 (15.3%) stated that no surgeons at their base hospitals performed LIHR.

Of the 124 respondents, 105 (84.7%) preferred the Lichtenstein method of open mesh repair, and 9 (7.3%) use the Mesh plug method. Five did not specify any method at all, and 2 (1.6%) favoured the prolene hernia system. In terms of the type and total cases of LIHR that surgeons perform, the results varied between TEP and TAPP repairs (Table 1).

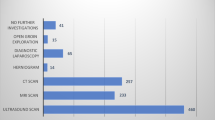

The study further looked into the routine practice of respondents in managing recurrent hernia after open repair and recurrent hernia after LIHR. For recurrent hernia after open repair, 48/124 (38.7%) surgeons replied that they would perform LIHR; 38/124 (30.6%) would refer their patients to another surgeon for LIHR; and 33/124 (26.6%) would perform open repair. The remaining five did not specify any form of repair, citing that it would depend on the patient. For recurrent hernia after LIHR, the majority 74/124 (59.7%) declared that they would perform open repair, 25/124 (20.2%) would refer to another surgeon for laparoscopic repair, 10 surgeons (8.1%) said that they would perform laparoscopic repair, while 15 other surgeons did not specify any method of repair.

For bilateral hernia, 48/124 (38.7%) respondents replied that LIHR would be their practice; 39 (31.5%) would perform open repair; and 35 (28.2%) would refer to another surgeon for LIHR. The remaining two said it would depend on the patient. These results are summarised in Table 2.

The study group was asked to select factors that were thought to be preventing LIHR from being adopted more widely. The results are summarised in Table 3. The cause most commonly cited was the lack of training opportunities (75/124, 60.5%). Other factors cited included mesh repair under local anaesthesia still being very effective (3/124, 2.4%), concerns about laparoscopic approach being more detrimental to patients if surgeon was not proficient in the technique (2/124, 1.6%), surgeons having to go through a steep learning curve after being established in open repair (2/124, 1.6%), surgeons being unwilling to adopt new surgical techniques (2/124, 1.6%); and insufficient facilities (2/124, 1.6%).

Most surgeons involved in this study felt that there was a need for hands-on courses in TEP repair for consultants (97/124, 78.2%). A total of 53 (42.7%) felt that the courses should last for a full day; 25 respondents (20.2%) felt that it should last for 2 days (25, 20.2%); 3 (2.4%) felt that the courses should last for more than 2 days; 33 respondents (26.6%) did not select any running time for the courses.

Discussion

The results of this survey provide an insight into the current views on the practice of inguinal hernia repair among consultant surgeons in Scotland. There is wide variation in the performance of hernia surgery but mesh repair remains the cornerstone of the treatment. Although LIHR was introduced 20 years ago, uptake remains very poor—related primarily to surgeons’ preferences and training. Although it is acknowledged that the clinical and cost effectiveness of LIHR is linked closely to the technical experience of the surgeon, systematic review of laparoscopic repair versus open indicates a faster return to usual activities, and less chronic pain or numbness. A recent study showed in a randomised comparison that LIHR has a lower rate of chronic pain (1.9 vs 3.5%) [10, 11]. Another study in England showed that chronic groin pain after hernia repair is one of the two most common causes of litigation [12]. This can be potentially reduced by LIHR. Nevertheless, there was no difference in complications and recurrence between open repair methods and LIHR [13, 14].

The principles of LIHR are to reduce the hernial sac, including its contents, and to strengthen the myopectineal orifice with a mesh so as to cover all the defects. Trans-abdominal pre-peritoneal repair (TAPP) and total extra-peritoneal repair (TEP) are the two approaches most frequently used for LIHR. In our survey about 36% of respondents perform TEP repair and 16% TAPP repair. A few may perform both.

Hernia surgery is slowly becoming a specialised surgery. A randomised control showed a high rate of complication in laparoscopic hernia and further recommended that LIHR should be undertaken by experienced surgeons [4, 15]. TAPP repair was associated with a higher incidence of morbidity due to vascular and visceral injuries, i.e. 0.13% with TAPP repair and none in TEP or open repair. Similarly, visceral injury rates of 0.79, 0.16 and 0.14% were noted in TAPP, TEP and open repair, respectively [1]. Our study showed that nearly three-quarters of surgeons believed lack of training to be the number one reason for the low performance of LIHR in Scotland. In fact, more than 80% of them wished to attend a hands-on course if conducted in Scotland. Interestingly, about 50% of consultants reported that there was still insufficient evidence for LIHR. NICE guidelines have clearly established that LIHR should be the preferred treatment of bilateral and recurrent hernia based on several systematic reviews and studies. In addition, it was recommended that LIHR should also form an option while discussing treatment of unilateral groin hernia. In a randomised control trial, Neumayer et al. [16] showed that LIHR for unilateral hernia had a higher recurrence, but if performed by experienced surgeons this difference was not significant. This highlights that hernia surgery, particularly LIHR, is a specialised surgery associated with a steep learning curve [17]. It is unlikely that further randomised trials may be conducted to address this issue. However, in our study, which included referral to other surgeons, about 70% of recurrent hernia after open surgery and bilateral hernia were repaired laparoscopically. Although the survey revealed a high rate of referral for laparoscopic repair, the results remains to be seen. About 30% of consultants in this survey thought lack of theatre time and cost constraints were barriers to adopting LIHR. In experienced hands, there was no difference in operating time between open and LIHR [18]. However, the learning curve is steep, and depends on understanding and familiarity of the pre-peritoneal groin anatomy. There is no absolute number but, as a rule of thumb, about 60–100 procedures may enable surgeons to undertake LIHR safely [5]. If reusable instruments are used, the cost of LIHR is easily justifiable [1, 17].

In summary, the reluctance to accept LIHR probably stems from fear of the steep learning curve, unfamiliarity with pre-peritoneal groin anatomy, and misperceptions regarding theatre time constraints. Attending hands-on courses then supervised procedures at the base hospital, followed by independent practice on carefully selected patients should overcome starting hurdles. A major issue is who should drive laparoscopic hernia surgery? Currently training depends largely on individual surgeon’s initiative and is supported by industry. Training issues are a global concern. A Danish study showed that only 15% of hernia repairs were performed laparoscopically. The study expressed concerns about the lack of training in LIHR for young surgeons. They proposed including LIHR training in the curriculum for higher surgical training and for established surgeons initiating courses [19]. Obviously, changes in practise from open surgery to LIHR demands different technical skills and an understanding of laparoscopic groin anatomy. A recent study recommended simulator-based training to improve mastery of the technical skills needed in laparoscopic surgery although more research is required in this area. In their study, Wilkiemeyer et al. [20] clearly established that period of training, level of experience of trainees, supervision, and the experience of the supervising surgeon were the factors most related to outcomes in open and laparoscopic hernia repair. Issues discussed included where to train residents and when to let them perform unsupervised, included simulated training, as well as better utilisation of operating room timing. They suggested that recurrence levels can be brought down if trainees are supervised by a surgeon who has performed more than 250 procedures. However, there is no set number to attainment of the learning curve and therefore UK NICE guidelines (2004) recommended that surgeons should conclude as to what constitutes appropriate training for LIHR locally. We think that a dual approach may be adopted. That is, for higher surgical trainees, LIHR should be included in the surgical curriculum, and, for established surgeons, hands-on courses, hernia master classes, mentoring and supervising in their parent hospital of participants performing their first few procedures, is possibly the way forward.

A limitation of this study was that some surgeons might not have received the survey questionnaire. We identified the names of consultants from the Scottish Audit of Surgical Mortality annual report 2007. It may be possible that new consultants who joined after 2007 were missed. Nevertheless, we had responses from all health boards, and thus the results represent current practice of LIHR in Scotland.

Conclusion

In Scotland, although a encouraging acceptance of LIHR was noted, contrary to NICE recommendations, 31.5 and 26.6% of consultant surgeons elected to repair bilateral and recurrent hernias, respectively, using the open approach. Addressing training and education is a priority to increase uptake of LIHR.

References

National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Technology appraisal guidance no 83: Guidance on the use of laparoscopic surgery for inguinal hernia. London: NICE, 2004 uptake report

Sanjay P, Woodward A (2007) A survey of inguinal hernia repair in Wales with special emphasis on laparoscopic repair. Hernia 11:403–407. doi:10.1007/s10029-007-0241-4

Stevenson AD, Nixon SJ, Paterson-Brown S (2010) Variation of laparoscopic hernia repair in Scotland: a postcode lottery? Surgeon 8:140–143. doi:10.1016/j.surge.2009.11.001

Hair A, Duffy K, McLean J, Taylor S, Smith H, Walker A, MacIntyre IM, O’Dwyer PJ (2000) Groin hernia repair in Scotland. Br J Surg 87:1722–1726

Tse GH, de Beaux AC (2008) Laparoscopic hernia repair. Scott Med J 53:34–37

McCormack K, Wake BL, Fraser C, Vale L, Perez J, Grant A (2005) Transabdominal pre-peritoneal (TAPP) versus totally extraperitoneal (TEP) laparoscopic techniques for inguinal hernia repair: a systematic review. Hernia 9:109–114. doi:10.1007/s10029-004-0309-3

Memon MA, Cooper NJ, Memon B, Memon MI, Abrams KR (2003) Meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials comparing open and laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair. Br J Surg 90:1479–1492. doi:10.1002/bjs.4301

McCormack K, Wake B, Perez J, Fraser C, Cook J, McIntosh E, Vale L, Grant A (2005) Laparoscopic surgery for inguinal hernia repair: systematic review of effectiveness and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess 9:1–203 iii–iv

Eklund A, Rudberg C, Smedberg S, Enander LK, Leijonmarck CE, Osterberg J, Montgomery A (2006) Short-term results of a randomized clinical trial comparing Lichtenstein open repair with totally extraperitoneal laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair. Br J Surg 93:1060–1068. doi:10.1002/bjs.5405

Eklund A, Montgomery A, Bergkvist L, Rudberg C, Swedish multicentre trial of inguinal hernia repair by laparoscopy (SMIL) study group (2010) Chronic pain 5 years after randomized comparison of laparoscopic and Lichtenstein inguinal hernia repair. Br J Surg 97:600–608. doi:10.1002/bjs.6904

Lau H, Patil NG, Yuen WK (2006) Day-case endoscopic totally extraperitoneal inguinal hernioplasty versus open Lichtenstein hernioplasty for unilateral primary inguinal hernia in males: a randomized trial. Surg Endosc 20:76–81. doi:10.1007/s00464-005-0203-9

Alkhaffaf B, Decadt B (2010) Litigation following groin hernia repair in England. Hernia 14:181–186. doi:10.1007/s10029-009-0595-x

Kald A, Anderberg B, Carlsson P, Park PO, Smedh K (1997) Surgical outcome and cost-minimisation-analyses of laparoscopic and open hernia repair: a randomised prospective trial with one year follow up. Eur J Surg 163:505–510

Butters M, Redecke J, Koninger J (2007) Long-term results of a randomized clinical trial of Shouldice, Lichtenstein and transabdominal preperitoneal hernia repairs. Br J Surg 94:562–565. doi:10.1002/bjs.5733

The MRC Laparoscopic Groin Hernia Trial Group (1999) Laparoscopic versus open repair of groin hernia: a randomised comparison. Lancet 354:185–190

Neumayer L, Giobbie-Hurder A, Jonasson O, Fitzgibbons R Jr, Dunlop D, Gibbs J, Reda D, Henderson W, Veterans Affairs Cooperative Studies Program 456 Investigators (2004) Open mesh versus laparoscopic mesh repair of inguinal hernia. N Engl J Med 350:1819–1827. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa040093

Wright D, Paterson C, Scott N, Hair A, O’Dwyer PJ (2002) Five-year follow-up of patients undergoing laparoscopic or open groin hernia repair: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Surg 235:333–337

Duff M, Mofidi R, Nixon SJ (2007) Routine laparoscopic repair of primary unilateral inguinal hernias–a viable alternative in the day surgery unit? Surgeon 5:209–212

Rosenberg J, Bay-Nielsen M (2008) Current status of laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair in Denmark. Hernia 12:583–587. doi:10.1007/s10029-008-0399-4

Wilkiemeyer M, Pappas TN, Giobbie-Hurder A, Itani KM, Jonasson O, Neumayer LA (2005) Does resident post graduate year influence the outcomes of inguinal hernia repair? Ann Surg 241:879–882 (discussion 882–884)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Shaikh, I., Olabi, B., Wong, V.M.Y. et al. NICE guidance and current practise of recurrent and bilateral groin hernia repair by Scottish surgeons. Hernia 15, 387–391 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-011-0797-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-011-0797-x