Abstract

Background: The study was undertaken in order to assess the degree of concordance between the patient’s and surgeon’s perceptions of adverse events after groin hernia surgery.

Methods: 206 patients who underwent elective surgery for groin hernia at Samariterhemmet, Uppsala, Sweden in 2003 were invited to a follow-up visit after 3–6 weeks. At this visit the patient was instructed to answer a questionnaire including 12 questions concerning postoperative complications. A postoperative history was taken and a clinical examination performed by a surgeon who was not present at the operation and did not know the outcome of the questionnaire. All complications noted by the physician were recorded for corresponding questions in the questionnaire.

Results: 174 (84.5%) patients attended the follow up, 161 men and 13 women. A total of 190 complications were revealed by the questionnaire, 32 of which had caused the patient to seek help from the health-care system. There were 131 complications registered as a result of the follow-up clinical examinations and history. Kappa levels ranged from 0.11 for urinary complications to 0.56 for constipation.

Conclusion: In general, the concordance was poor. These results emphasise the importance of providing detailed information about the usual postoperative course prior to the operation. Whereas the surgeon, from a professional point of view, has a better idea about what should be expected in the postoperative period and how any complications should be categorised, only the patient has a complete picture of the symptoms and adverse events. This makes it impossible to reach complete agreement between the patient’s and surgeon’s perceptions of complications, even under the most ideal circumstances.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Quality assessment involves registration of all adverse outcomes of the interventions in question as perceived by the patient. Since 1992 the Swedish Hernia Register has continuously provided an easily available measure of outcome to all participating units, which has led to an improvement in the quality of hernia surgery in terms of reoperation rate [1, 2, 3]. As the recurrence rate in recent years has gradually decreased, other outcome measures have become more dominant [4]. One of the most important of these measures is the postoperative complication rate. In addition to the immediate discomfort caused by the complication, it is also important as a major risk factor for recurrences [1, 5]. This makes it useful as an intermediate variable, providing an early measure of quality, and it gives immediate feedback to the health-care provider [6]. This is also in accordance with the patient’s perception of the long-term outcome after an operative intervention. In a retrospective questionnaire study including patients operated on for hernia recurrence, poor surgical technique was perceived as a major cause of recurrence [7].

One problem with postoperative complication as outcome measure is that it is more difficult to define as objectively and stringently as a recurrence. The procedure of registering postoperative complications in the Swedish Hernia Register varies locally. In some cases the data are assembled by nurses responsible for follow-up, and in other cases they are based on clinical examination or study reports. In addition to the problem of incoherence in follow-up routines, discordance between the view of the patient and the surgeon on the postoperative course and any non-predicted events may also obscure the outcome. In order to validate the procedure for recording complications in the Swedish Hernia Register and to assess discordance between the patient’s and surgeon’s perceptions of postoperative complications, the findings at a clinical examination performed by an independent surgeon were compared with what the patient stated in a standardised questionnaire 3–6 weeks after their operation.

Materials and methods

From the group of patients who underwent elective surgery for groin hernia at the Samariterhemet, Uppsala, in 2003, 206 consecutive patients were given an appointment 3–6 weeks after their operation. At this visit the patient was asked to answer a questionnaire (Table 1).

The first two questions regarded the patient’s overall perception of the immediate postoperative period and adverse events that occurred during the first postoperative month. The remaining questions addressed specific postoperative complications, having three alternative answers:

-

No

-

Yes, but I have not sought help from the health-care system

-

Yes, I have sought help from the health-care system

These three alternatives were designed to be able to distinguish between complaints that should have come to the knowledge of the surgeon and thereby recorded in the Hernia Register and complications that the patient had not sought help for. In the Swedish Hernia Register, complications are divided into bleeding, infection, severe pain and other complications, corresponding to questions 3, 4, 6, and 12.

After the patient had filled in the questionnaire, a clinical examination was performed by a surgeon who had not participated in the operation. All four authors participated in the clinical examinations. A careful patient history was taken and the groin inspected. Any complication notified by the surgeon was recorded according to the questions in the questionnaire. The surgeon was not aware of how the patient had answered.

Statistics

Agreement between the patient’s perception and the surgeon’s perception was estimated using Kappa levels. The two categories “Yes, but I have not sought help from the health-care system” and “Yes, I have sought help from the health-care system” were combined to form one positive category when Kappa was estimated. Kappa is a measure of agreement between two different assessments of a categorical variable [8]. With Kappa=1 there is 100% agreement, 0.75–1 is excellent agreement, and 0.4–0.75 is fair-to-poor agreement.

Results

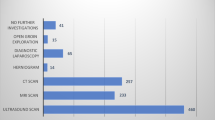

Of the 206 patients invited to follow-up, 174 (84.5%, 161 men and 13 women) filled in the questionnaire and underwent clinical examination. Mean age was 55 years, standard deviation 14 years. Complications as perceived by the surgeon versus complications as perceived by the patient, independent of type of complication, are shown in Fig. 1. Complications as perceived by the surgeon versus complications as perceived by the patient, stratified for type of complication, are shown in Table 2. Other complications stated by the patients included borborygmia, tension in the wound, numbness, induration in the wound, remaining suture, hernia recurrence on the opposite side to the operation, back pain, anal pain, loss of sensitivity in the leg, burning sensation, tooth injury, increased spermatocele, anal incontinence, prolonged time to ejaculation, chest pain and increased tinnitus. Other complications noted at the clinical examination included burning sensation around the wound, loss of sensibility, ejaculatio tarda, back pain, seroma, injury to the spermatic cord, tension in the wound, subcutaneous induration, scrotal swelling, urinary incontinence, increased tinnitus, and loss of sensibility in the heel. Altogether the patients stated 190 complications, and they had sought help from the health-care system for 32 of these. There were 131 complications registered at clinical examination. Kappa values ranged from 0.11 to 0.56. Lowest Kappa values were seen for urinary symptoms and anaesthesiological complications, both below 0.3. Constipation was the only variable that had a Kappa value higher than 0.5.

Discussion

Patient satisfaction is one of the main goals of health-care. However, if health-care providers are to take responsibility for all interventions, the surgeon and patient have to agree on what should be considered a successful outcome [9]. The authorisation to interfere with the health of the patient provided by knowledge superior to the layman does not give the surgeon the sole right to set the ultimate goal of treatment given. For most patients, absence of recurrence is the most important outcome measure [10]. With the decreasing recurrence rate in recent years, other indicators of quality, such as postoperative complications, have become more dominant. However, whereas a recurrence can be defined objectively and with high agreement between the patient’s and surgeon’s perceptions [4, 11], this is more difficult to achieve for postoperative complications. This may be due to a more or less conscious inclination of the surgeon to ignore a failure of the procedure, normal postoperative healing that the insufficiently-prepared patient perceives as something diverging from the expected course of events, or because the complication for some reason has not come to the attention of the surgeon.

In general, there was poor concordance between the answers to the questionnaire and the outcome from the clinical examination. The Kappa levels were spread over a continuum from 0.11 for urinary complications to 0.56 for constipation. To some extent the low Kappa levels may be explained by the patient’s inability to distinguish between different diagnoses. If all complications are combined into one category, Kappa becomes 0.43 (Fig. 1), which is slightly higher than for most of the subgroups. This is, however, still unsatisfactory if the aim is to record all complications relevant for the patient. The total number of complications registered was slightly higher in the questionnaire than at the follow-up visit, which also partly accounts for the discordance.

One of the more striking differences between complications recorded at the clinical examination and in the questionnaire was the low rate of severe pain and testicular pain recorded by the surgeon when the patient gave a positive answer to the same question in the questionnaire (Table 2). Only 13 of 35 patients (37%) who stated that they had suffered from testicular pain were recorded by the surgeon as also having the same complication. For severe pain the same figure was 14 of 34 patients (41%). This reflects how difficult it is to be attentive to purely subjective complications when these are not associated with objective clinical signs, and also partly explains why more complications were stated by the patients than by the surgeons.

If the patient is carefully informed in advance of what should be expected in the postoperative period, anxiety and frustration can probably be avoided and a better mutual understanding between the surgeon and patient achieved [12, 13]. One cannot, however, predict every event that may occur in the postoperative period and it may become difficult for the patient to discriminate between an adverse event and an essentially normal postoperative course. There is no definition of what the threshold between normal postoperative bleeding and a hematoma to be recorded as a complication is. The limit must be set by the subjective symptoms of the patient. The role of the patient as the only one able to judge the outcome is even more pronounced for purely subjective complications, such as severe postoperative pain and pain in the testicle.

Some caution must be taken when interpreting the results of our study. In a study where postoperative complications following hip arthroplasty, assessed using a self-administered questionnaire, were compared to those recorded at clinical examination, a discordance between the outcomes of the questionnaire and the clinical examination—similar to that in our study—was seen [14]. Although it could not be ruled out that outcome measures developed and administered by clinicians are subject to bias from several sources, it was concluded in that study that patient questionnaires also have their limitations. The answers to patient questionnaires depend on the patients’ understanding of the questions asked and, as with all written questions, may be subject to misinterpretation.

Our results show a discordance between the patient’s and surgeon’s view, but we cannot determine which view should be set as the norm to the other. Whereas the surgeon, from a professional point of view, has a better knowledge of what should be expected in the postoperative period and how adverse events should be categorised, the patient’s authority as the only one who can describe his or her own symptoms and inconvenience cannot be questioned. This makes it impossible to reach a complete agreement between the patient’s and surgeon’s perception, even under the most ideal circumstances. Instead of considering them as two contradicting outcomes, they can be treated as two separate measures of quality, with equilibrate weighting.

Standardised procedures for follow-up after hernia surgery may avoid some of the disagreement between the patient and physician and reduce frustration and anxiety. In a previous study it was shown that patients usually give higher priority to an outpatient appointment after the operation than prior to it [15]. The preoperative visit, however, is indispensable if thorough information is to be given to the patient about what may be expected under and after their operation. One way of organising this would be to have a planned follow-up telephone call from a nurse, or a postal questionnaire, as well as a visit to the surgeon responsible in selected cases where the patient has noted divergence from the expected postoperative course.

Our results raise concern about the principles used for recording complications in the Swedish Hernia Register. Comparison of register and questionnaire outcomes may be of value when assessing the validity of the register, although the discordance between patient and surgeon makes it impossible to use a questionnaire as an unequivocal standard for validation.

If complications are to be used as an intermediate variable, they have to be defined, including clear criteria and method of recording. One way of assessing the external validity of the questionnaire would be to perform deep-going interviews with 10–20 patients who have filled in the questionnaire after a hernia operation. Another approach would be to use the outcomes of the questionnaire and the Swedish Hernia Register as two separate intermediate variables, with long-term pain or recurrence as the ultimate outcome. In this way the perception of the surgeon and the patient are used as two parallel variables, without assigning a higher external validity to either of them.

The problem of registering postoperative complications is common to most quality registers based on a specific intervention. Adverse events following the intervention are, in most cases, a fundamental measure of outcome and one of the main intermediate variables [16, 17]. It is, however, difficult to define standardised procedures for registering complications [18, 19, 20, 21]. In most cases it is based on a composite of data assembled by nurses responsible for follow-up, directed clinical examination by the surgeon responsible, symptoms spontaneously reported by the patient, and study reports. Our results show that data assembled in this way must be interpreted with great caution. If routines for recording complications are not standardised, they should only be used for audit and not for comparison between different units.

References

Nilsson E, Haapaniemi S, Gruber G, Sandblom G (1998) Methods of repair and risk for reoperation in Swedish hernia surgery from 1992 to 1996. Brit J Surg 85:1686–1691

Sandblom G, Gruber G, Kald A, Nilsson E (2000) Audit and recurrence rates after hernia surgery. Eur J Surg 166:154–158

Nilsson E, Haapaniemi S (1998) Hernia registers and specialization. Surg Clin North Am 78:1141–1155

Haapaniemi S, Nilsson E (2002) Recurrence and pain three years after groin hernia repair. Validation of postal questionnaire and selective physical examination as a method of follow-up. Eur J Surg 168:22–28

Sandblom G, Haapaniemi S, Nilsson E (1999) Femoral hernias: a register analysis of 588 repairs. Hernia 3:131–134

Gunnarsson U (2003) Quality assurance in surgical oncology—colorectal cancer as an example. Eur J Surg Oncol 29:89–94

Gunnarsson U, Heuman R (1999) Patient experience ratings in surgery for recurrent hernia. Hernia 3:69–73

Armitage P, Berry G (1994) Further analysis of categorical data. In: Armitage P, Berry G (eds) Statistical methods in medical research. Blackwell Science, Oxford, pp 443–7

Durieux P, Bissery A, Dubois S, Gasquet I, Coste J (2004) Comparison of health care professionals’ self-assessments of standards of care and patients’ opinions on the care they received in hospital: observational study. Qual Saf Health Care 13:198–202

Lawrence K, McWhinnie D, Goodwin A, Doll H, Gordon A, Gray A, Britton J, Collin J (1995) Randomized controlled trial of laparoscopic versus open repair of inguinal hernia: early results. Brit Med J 311:981–985

Kald A, Nilsson E (1991) Quality assessment in hernia surgery. Qual Assur Health Care 3:205–210

McManus PL, Wheatley KE (2003) Consent and complications: risk disclosure varies widely between individual surgeons. Ann Roy Coll Surg 85:79–82

Gilbert AI (1993) Medical/legal aspects of hernia surgery. Personal risk management. Surg Clin North Am 73:583–593

Ragab AA (2003) Validity of self-assessment outcome questionnaires: patient-physician discrepancy in outcome interpretation. Biomed Sci Instrum 39:579–584

Gunnarsson U, Heuman R, Wendel-Hansen V (1996) Patient evaluation of routines in ambulatory hernia surgery. Ambulat Surg 4:11–13

Bonsanto MM, Hamer J, Tronnier V, Kunze S (2001) A complication conference for internal quality control at the Neurosurgical Department of the University of Heidelberg. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 78:139–145

Herbert MA, Prince SL, Williams JL, Magee MJ, Mack MJ (2004) Are unaudited records from an outcomes registry database accurate? Ann Thorac Surg 77:1960–1964

Hanto DW (2003) Reliability of voluntary and compulsory databases and registries in the United States. Transplantation 75:2162–2164

Wynn A, Wise M, Wright MJ, Rafaat A, Wang YZ, Steeb G, McSwain N, Beuchter KJ, Hunt JP (2001) Accuracy of administrative and trauma registry databases. J Trauma 51:464–468

Gunnarsson U, Seligsohn E, Jestin P, Pahlman L (2003) Registration and validity of surgical complications in colorectal cancer surgery. Brit J Surg 90:454–459

Dreisler E, Schou L, Adamsen S (2001) Completeness and accuracy of voluntary reporting to a national case registry of laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Int J Qual Health Care 13:51–55

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fränneby, U., Gunnarsson, U., Wollert, S. et al. Discordance between the patient’s and surgeon’s perception of complications following hernia surgery. Hernia 9, 145–149 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-004-0310-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-004-0310-x