Abstract

The aim of this study is to investigate associations between use of cigarettes, cannabis, and alcohol (CCA) and psychosocial problems among adolescents with different cultural backgrounds living in Nordic countries. Data from six questionnaire-based surveys conducted in Denmark, Norway, and Greenland, with participants from different cultural and religious backgrounds, were compared. A total of 2212 adolescents between 15 and 18 years of age participated in the study. The surveys were carried out nationally and in school settings. All adolescents answered a 12-item questionnaire (YouthMap12) with six questions identifying externalizing behavior problems and six questions identifying internalizing behavior problems, as well as four questions regarding childhood neglect and physical or sexual abuse, and questions about last month use of CCA. Externalizing behavior problems were strongly associated with all types of CCA use, while childhood history of abuse and neglect was associated with cigarette and cannabis use. The associations did not differ by sample. Despite differences between samples in use of CCA, national, cultural, and socioeconomic background, very similar associations were found between psychosocial problems and use of CCA. Our findings highlight the need to pay special attention to adolescents with externalizing behavior problems and experiences of neglect and assault in CCA prevention programs, across different ethnic and socioeconomic backgrounds.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Nordic countries are often viewed as being very comparable with regard to social politics and level of welfare. Norway and Denmark in particular share a very similar language and were historically united with Norway being under Danish rule from 1387 to 1814 [1]. Greenland, at that time an island with Norse settlements, remained under Danish rule after Norway became an independent state. However, real attempts to modernize the country and assimilate a more Danish culture into the Greenlandic population only began in the middle of the 20th century. With the introduction of Home Rule in 1979, Greenland has gradually regained autonomy; however, Danish is still taught in schools and Greenland is still highly dependent on Danish subsidies, just as Denmark still controls Greenlandic foreign affairs and defense policies [2].

Despite these historical ties, comparable welfare systems, similar language, and the ethnical homogeneity that characterizes the Nordic countries, differences in the use of cigarettes, cannabis, and alcohol (CCA) have been found in the young population [3]. The European school survey project on alcohol and other drugs (ESPAD) from 2015 among adolescents aged 15–16 years [3] showed that the prevalence of last month use of cigarettes was 10% in Norway and 19% in Denmark, while a school survey in Greenland from 2014 found that 47% of adolescents aged 15–17 years smoked cigarettes daily [4]. The ESPAD report also showed that 2% of Norwegian and 5% of Danish adolescents had used cannabis in the last month [3], while the school survey in Greenland found that 9% of 15–17 years old had used cannabis within the last month [4]. The frequency of alcohol use in the last month ranged from three occasions in Norway to six occasions in Denmark [3], while a school survey study from 2011 found that 20% of Greenlandic 10th graders reported drinking alcohol at least once a week [5].

These numbers represent CCA use in the general young population in these Nordic countries. On a national level, little is known about CCA use among adolescents with non-Scandinavian cultural backgrounds living in these countries. However, ethnic differences in CCA use do appear to exist. The youth@hordaland survey found that ethnic Norwegian adolescents were less likely to smoke cigarettes and use illicit drugs than minority adolescents from countries within the European Union, European Economic Area or the US (EU/EEA countries) and more likely to use alcohol or smoke cigarettes than minority adolescents from non-EU/EEA countries [6].

Adolescents who initiate CCA use at a young age and develop problems related to CCA use are at an increased risk of educational dropout [7, 8], and thus risk becoming marginalized with little or no attachment to work life. Preventing initiation of CCA use in adolescents is, therefore, of major importance. However, use, and particularly regular use, of CCA among adolescents must be understood in the context of their social and/or psychological life in general, and in relation to other risk-taking behaviors such as criminal behavior, risky sexual behavior, and driving-related risks [9].

One of the most widely agreed upon frameworks in developmental psychopathology is the subdivision of disorders into externalizing and internalizing psychopathology [10]. Examples of internalizing symptoms are depressive thoughts, anxiety, feelings of loneliness, suicidal ideation, and deliberate self-harm. Externalizing behaviors, on the other hand, consist of a class of behaviors that are manifested in outward behaviors and reflect a person acting negatively upon the external environment including oppositional, aggressive, impulsive, disruptive, hyperactive, and rule-breaking behavior.

Externalizing behavior problems have generally been found to predict both substance use and substance use disorders [11, 12]. Longitudinal studies have found a strong positive relationship between the presence of externalizing behaviors in childhood and subsequent substance use in adolescence [13,14,15]. Some of the more robust findings are positive associations between conduct problems and subsequent heavy use of alcohol [16,17,18].

In addition, externalizing behavior problems have been found to be relatively stable and to carry with them a poor outcome prognosis [19], partially mediated by early onset substance use and school problems [20]. Both externalizing and internalizing behavior problems have been reported to be associated with tobacco smoking [21,22,23,24], and adolescent cannabis use has been linked with disorders that are rooted in externalizing problems, such as attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and conduct disorder [25, 26], as well as more general mental health and social problems [27,28,29,30]. Several studies have found no or very modest associations between internalizing behavior problems and use of CCA [13, 30,31,32,33,34,35].

While some children may be predisposed towards developing externalizing or internalizing behavior problems [36], environmental factors, such as child maltreatment and growing up in poor neighborhoods, enhance the risk of developing these types of behavior problems [31, 36]. Moreover, stressful or traumatic experiences such as childhood neglect and physical or sexual abuse have been found to be associated with substance use [31, 37, 38].

Although different psychosocial problems have been shown to add to the risk of developing substance use problems in adolescence, there may also be differences in the causes and patterns of substance use in adolescents and youth depending on their cultural or ethnic background. The previous studies have found significant ethnic differences in the patterns of adolescent substance use [39,40,41]. A study in the US by James et al. [42] found that high cultural identity (i.e., identity that is associated with positive attitudes towards and a sense of belonging to one’s ethnic group) was positively associated with heavy drug use in adolescence. Furthermore, cultural identity was more prominent in ethnic minority youth than in Caucasian youth. However, James et al. argue that social influences rather than ethnicity play a large part in the development of drug use in youth. Ethnic or racial differences in age of initiation, course, and duration of substance use was also found in a large longitudinal study from the US by Chen et al. [43], who argue that future research should focus on identifying both the common and unique mechanisms that may increase the risk of adolescent substance use.

In many settings, a comprehensive assessment of a full spectrum of psychopathology may not be feasible. This includes large-scale population surveys as well as studies of clinical populations that may either be difficult to reach, or have difficulties completing long test batteries or self-report assessments. Recently, the YouthMap12 questionnaire (Appendix 1) was developed as a brief measure of externalizing and internalizing spectrum difficulties, and it was found to have adequate psychometric properties. The externalizing factor was, as expected, strongly associated with substance use and use of psychotropic medication in a population-based sample of adolescents and young adults [32]. However, the validation study of the YouthMap12 relied on respondents from a single country with an ethnically homogeneous population, restricting the generalizability to other cultures.

The aim of the present study was to investigate whether associations between psychosocial factors and CCA use among adolescents are similar across, or specific to, different Nordic countries or ethnic and socioeconomic backgrounds. This was done by examining CCA use in six samples including adolescents from Denmark, Greenland, and Norway with either Danish or Norwegian ethnic background, Arabic background, Inuit background, or mixed cultural background other than Danish or Norwegian. Concerning the relationship between psychosocial factors and CCA use, we tested whether the association between psychosocial factors and substance use differed by sample.

Methods

Samples

Data were drawn from the following separate surveys:

(1) The National YouthMap Survey 2014 (NYS2014 DK): participants aged 15–18 years were randomly drawn from the central person register by Statistics Denmark (the central authority on Danish statistics). Potential respondents were invited by postal letter to complete a Web-based questionnaire. Telephone interviews were conducted with those individuals who had not responded after two reminders. This resulted in a total of 1104 participants representing a response rate of 77%. No immigrants or second-generation immigrants were included in this sample and only adolescents who were enrolled in educational activities were included.

(2) The Gentofte YouthMap Survey 2015 (Gent2015 DK): Gentofte is the wealthiest municipality in Denmark. The mean total family income in 2014 was 115,093 EUR for a family in Gentofte versus 64,474 EUR for an average Danish family. The same procedure as NYS2014 was used. This sample consisted of 450 respondents (aged 15–18 years) representing a response rate of 70%. Again, no immigrants or second-generation immigrants were included in the sample and only adolescents who were enrolled in educational activities were included.

(3) The Aarhus School-Based Survey 2014 (Aarhus2014 Arabic): students from 10th grade aged 15–17 years with an Arabic cultural background living in Aarhus, the second largest city in Denmark, were invited to participate in the study. In total, 122 completed the questionnaire representing a response rate of 62%. In Denmark, 10th grade is optional. After 9th grade, Danish students are typically divided into students enrolled into continuation/boarding schools (living outside home), upper secondary education (high schools), or a local 10th grade (living at home) typically preparing the students for an upper secondary or vocational education. The students from this sample belonged to the latter category.

(4) and (5) The Stavanger School-Based Survey 2016: Stavanger is the fourth largest city in Norway. The oil industry has its main seat in Stavanger; and for many years, Stavanger was one of the richest municipalities in the country. Upper secondary students aged 16–18 years were invited to participate in the study. In total, 451 students completed the questionnaire representing a response rate of 72%. The Stavanger sample was subsequently divided into ethnic Norwegian students (N = 362, Stav2016 N) and immigrant and second-generation immigrants (N = 89, Stav2016 N mixed). The two upper secondary schools from which the samples are drawn are located in the Stavanger region and offer most curriculums available in Norway. Thus, it is assumed that the schools are representative for upper secondary students in the Stavanger region.

(6) The Nuuk School-Based Survey 2014 (Nuuk2014): students aged 15–16 years with an Inuit cultural background living in Nuuk participated in the study. Nuuk is the Capital of Greenland with approximately 17,000 inhabitants (total inhabitants of Greenland is approximately 56,000). The study was carried out in the four schools that offer 10th grade (lower secondary) in Nuuk. In total, 175 student attended 10th grade at the time of the study. Because of technical problems in one of these schools, only 102 questionnaires were completed. Non-Greenlandic students were excluded from the data yielding 85 answers for analysis. The 10th grade in Nuuk corresponds to the 9th grade in Denmark. The sample does not represent all 10th grade students living in Nuuk, since the school with the highest number of incomplete questionnaires also has the highest number of socially disadvantaged students.

All participants gave their consent and the surveys were approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency just as all confidentiality and privacy requirements were met.

Measures

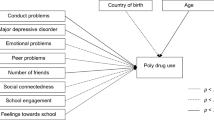

YouthMap is a measure developed to monitor individual psychosocial problems or resources and substance use among adolescents and young adults [44]. In this study, specific attention was paid to the YouthMap12, which is a subset of 12 items measuring psychological and behavioral problems drawn from the complete YouthMap questionnaire. The 12 items are divided into two factors—an externalizing problem factor (EP6), which includes 6 questions about problem behaviors in school (troublemaker, disruptive in classroom, conflict with teacher, truancy, expelled from school) and violent behavior in general, and an internalizing problem factor (IP6) which includes 6 questions about depression, anxiety, feelings of loneliness, suicidal ideation, deliberate self-harm, and eating disorders. The 12 items were initially selected from standardized and widely used questionnaires including the European Adolescent Drug Abuse Diagnosis [45] and the European Addiction Severity Index [46] (for a more detailed description of the selection process, please see [32]).

The construction of the two YouthMap12 factors and their reliability and stability are described in detail in a validation study by Pedersen et al. [32], which included youth aged 15–25 years. The study found Cronbach’s alpha (α) between 0.71 and 0.75 for EP6 and between 0.75 and 0.80 for IP6. In the present study, α for EP6 ranged between 0.60 (Nuuk) and 0.80 (Aarhus2014 Arabic), while α for IP6 ranged between 0.76 (Gent2015) and 0.88 (Stav2016 N mixed).

In addition to YouthMap12, we used the Neglect Assault Index (NAI4) which includes the following four questions: (1) Have you ever been subjected to neglect? (2) Have you ever been subjected to sexual assault or sexual abuse? (3) Have you ever been subjected to physical assault or abuse? (4) Has someone ever made threats to your life or to seriously injure you? The four questions are answered by yes or no (max score 4) and are similar to items used in other surveys, [47]. Factor analysis and α showed that NAI4 did not constitute a single reliable factor. Therefore, NAI4 should be thought of as an index of number of lifetime neglect/assault experiences.

To measure use of CCA, we used last month prevalence. Initially, we used the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA) classification of drug use last month which divides use into the following categories: 1–3 days, 4–9 days, 10–19 days, and 20+ days [48]. However, most of these categories were not applicable for the six samples of adolescents. In the Stav2016 N mixed sample, only one person had smoked cigarettes 20+ days and only three persons had used cannabis 4+ days the last month. Therefore, we chose to dichotomize the CCA categories and defined use of CCA as follows: Cigarettes 1+ days last month, cannabis 1+ days last month, and alcohol 4+ days last month. While these cutoffs may appear low in terms of identifying problematic use of substances, the participants in the samples are very young and hence at an age that has previously been used as a cutoff for the early initiation of cannabis use [49]. The higher cutoff for alcohol is explained by the relative normalization of alcohol use among Nordic adolescents. Data about cigarette smoking were not available from the Nuuk2014 sample.

Translation of YouthMap (which includes YouthMap12, NAI4, and measures of CCA use) from Danish to Greenlandic was carried out by psychology students fluent in both Danish and Greenlandic language. Since the Danish and Norwegian languages are very similar, especially in writing, the translation of the questionnaire from Danish to Norwegian was carried out by Norwegian researchers familiar with the Danish language.

Statistical analysis

We used binomial logistic regression analyses and adjusted odds ratios (AOR) to estimate associations between CCA use and scores in EP6, IP6, and NAI4. All associations between EP6 and CCA use were adjusted for age, IP6 and NAI4; all associations between IP6 and CCA use were adjusted for age, EP6 and NAI4, and finally, all associations between NAI4 and CCA use were adjusted for age, IP6 and EP6.

To assess differences between samples, we conducted interaction analysis using samples as a nominal predictor and the EP6, IP6, and NAI4 as continuous indicators. In each case, we used the Bayesian information criterion (BIC) and Akaike information criterion (AIC) to determine whether a model with an interaction between sample and continuous predictor was superior to a model with only the sample and the continuous predictor. The BIC and AIC are indicators of model fit that takes on smaller values as model fit improves, but higher values as the number of parameters in the model increases. Thereby, the BIC/AIC are informative in indicating whether or not a model that includes further terms improves model fit.

Results

Demographic differences and similarities between the six samples are presented in Table 1.

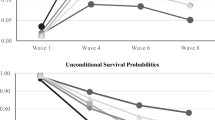

Prevalence of CCA use and psychosocial problems in the six samples

The prevalence of CCA use is presented in Table 2.

The sample selections and the data collection method were not identical for the six samples, and therefore, it is not possible to compare the different samples with each other. Nevertheless, it is in line with reports from the ESPAD studies that CCA use is much higher among Danish than Norwegian youth and that cannabis use among the youngest adolescents from Greenland is high [3].

Table 3 shows the prevalence of psychosocial problems in the six samples. To provide an estimate of how common it is for a respondent from a given sample to have an elevated score on a given scale, we defined scores on the EP6, IP6, and NAI4 close to the 90th percentile or above as elevated. The value for all three indicators was 2 or more.

The groups differed in terms of externalizing behavior problems [χ2(5) = 24.71, p < 0.001], with the Arabic Aarhus sample most likely to report elevated externalizing problems, followed by the mixed Norwegian sample and the Ethnic Inuit sample. In terms of internalizing behavior problems, the groups again differed substantially [χ2(5) = 76.55, p < 0.001], with the Inuit sample being most likely to report elevated internalizing problems, followed by the mixed Norwegian sample. In terms of neglect and abuse, we did not find significant differences in bivariate analysis (χ2(5) = 9.10, p = 0.105).

Table 4 shows the multivariate associations between psychosocial risk factors and CCA use. Externalizing behavior problems and abuse/neglect were both associated with all types of CCA use, whereas internalizing behavior problems were significantly associated with cigarette use only.

Table 5 shows the information criteria for models with versus without interaction terms between scales and sample.

In one single case, a significant improvement in log-likelihood was found when including an interaction between sample and internalization in predicting cigarette smoking (p = 0.03). However, given that the BIC indicates that a model without interaction was superior to a model including the interaction, we chose not to analyze this interaction further.

Discussion

This study yielded robust support for a strong link between externalizing behavior problems and CCA use across samples. These findings support the use of YouthMap12 as a measure of the externalizing/internalizing spectrum of psychopathology in situations, where it is not feasible to administer longer instruments.

The findings mirror what is known in general about the associations between substance use and externalizing/internalizing pathology: Strong positive associations between externalizing behavior problems and CCA use have been found in numerous studies (e.g., [13,14,15]), whereas associations between internalizing behavior problems or trauma history and CCA are much more varied.

Findings from the present study indicate that these associations exist across national, cultural, as well as socioeconomic background. We found no support for differences in the associations between any of our scales and any type of substance use across samples.

Of the three types of psychosocial factors examined in the present study, externalizing behavior problems were most predictive of CCA use. In addition, trauma history was associated with cannabis and cigarette use, and internalizing behavior problems were associated with cigarette use. The findings might well differ in other cultural settings.

Across the Nordic countries, cigarette smoking has become a more devalued vice, and tobacco products and consumption have become highly regulated and restricted. This regulation and devaluation can be linked to a strong decrease in cigarette smoking among youth in the Nordic countries (ESPAD group 1995 and 2015). The traditional de-normalization strategies seek “to change the broad social norms around using tobacco—to push tobacco use out of the charmed circle of normal, desirable practice to being an abnormal practice” [50, p. 225]. When this de-normalization strategy is successful, it could be argued that those who continue to smoke, despite the fact that society and very often also the close social network find it unhealthy and deviant, are either rebellious, unable to stop (loss of control), or use it to reduce tension, anxiety, etc. (self-medication). Furthermore, evidence suggests that the perceived positive effects of nicotine may be particularly strong in individuals who have traits that are linked to externalizing behavior problems, such as impulsivity and hyperactivity. For instance, an experimental study showed that individuals with high levels of impulsivity experienced greater relief from experimentally induced negative affect after smoking a nicotinized vs. a non-nicotinized cigarette, compared to individuals with low levels of impulsivity [51]. Similarly, Gardner [52] found a clear link between nicotine consumption and increases in executive attention leading to a better regulation of negative affective states in vulnerable youth. Moreover, while various mental disorders have been found to be predictive of tobacco smoking in youth, early onset smoking has been found to predict disruptive disorders, including oppositional defiant disorder, ADHD, and conduct disorder [53]. For adolescents with ADHD, acute nicotine administration has been found to significantly reduce ADHD symptom severity as well as self-reported depressive mood [54] and nicotine appears to have positive effects on both cognitive and behavioral inhibition in adolescents with ADHD that are comparable to or exceed the effects of methylphenidate [55]. While these findings relate to inherent traits or more severe disruptive disorders, some of the actions that nicotine appears to have may also help to explain the association between externalizing behavior problems and cigarette use reported here. As Gardner [52] has argued, nicotine may serve a self-regulatory function for vulnerable youth which may dampen negative emotions and make it easier to cope. Smoking may also provide a social lubricant, since the early cigarette smoking and affiliating with deviant peers are highly related [56].

The positive association between cannabis use and externalizing behavior problems is well established [13, 15] and we also found significant positive associations between the two in the present study. While many who initiate cannabis use in adolescence have not manifested externalizing behavior problems in childhood [11], externalizing problems have been found to increase the risk of cannabis use initiation in adolescence regardless of whether the behaviors were manifested in the early childhood or first appeared during adolescence [15]. In addition, although cannabis use and dependence may be accompanied by symptoms mimicking externalizing behaviors, longitudinal studies have found that externalizing behavior problems predate cannabis use [11, 13]. On the other hand, children who display childhood-limited externalizing behavior problems are not at an increased risk of initiating cannabis use in adolescence [15], which indicates that changes in behavior during childhood and adolescence may reduce the risk of later cannabis use and hence provides a foundation for the possible usefulness of early interventions.

Use of alcohol is very common in all Nordic countries and some level of binge drinking is not uncommon. In spite of this, we found a significant association between our measure of drinking more than four times in the past month and externalizing behaviors. This may suggest that even in a cultural setting in which alcohol use is quite widespread, frequency of drinking may differ by degree of externalizing behavior problems.

The previous studies have shown mixed findings regarding the role of internalizing behavior problems as a risk factor for CCA use [34, 35, 57, 58]. In fact, internalizing behavior problems (when adjusted for externalizing behavior problems) may to some degree, and under certain circumstances, protect against developing substance use in early adolescence [34, 35, 58]. In the present study, internalizing behavior problems were only significantly positively associated with cigarette use and the effect was small.

We found no associations between alcohol use and traumatic events in the total samples.

Implications for practice

Regular CCA use is associated with externalizing behavior problems in adolescents across culture, ethnicity, and gender in the Nordic countries, indicating that this factor is an important general indicator of risky behavior in adolescence. The results strongly indicate that prevention strategies initiated in childhood with at-risk children, as well as social interventions of substance use problems among adolescents, should take externalizing behavior problems (and, to some extent, traumatic experiences) into consideration. The efficiency of various social interventions may well depend on different cultural ways of understanding the intervention, but the risks of developing substance use problems seem to be similar across cultural backgrounds and relate most strongly to externalizing behavior problems, and the measurement is simple and straight-forward.

Strength and limitations

One of the strengths in this study is the high response rate across countries and regions, especially for this age group. Some limitations with regard to the findings presented here must also be mentioned. First, because of the relative size of the sample, the Danish national sample weighed rather heavily in our analyses. This may have affected the results as Danish youth have the highest consumption of alcohol in Scandinavia [3]. Similarly, cannabis use is more prevalent among Danish youth than in other Nordic countries. Second, the Greenlandic sample consists of responses from three of the four schools in Nuuk who offer 10th grade. Because of technical difficulties, it was not possible to obtain data from one of the schools. As this school has the highest number of disadvantaged students from Nuuk, the findings may be limited to youth who have come from more stable backgrounds and hence may explain the relative low incidence of traumatic experiences reported by the participants from Nuuk compared to findings in other studies [59].

A further limitation is the cross-sectional design, which means that reverse causality cannot be entirely ruled out. Therefore, the present study supports the existence of a relationship between externalizing behavior problems and substance use, but does not in itself inform us on the direction of the causality. In addition, the items used to assess externalizing behavior problems in this study refer exclusively to childhood behaviors, and a respondent’s recollection of his or her own behavior during childhood may be influenced by recent substance use.

Conclusion

This study found significant positive associations between externalizing behavior problems as well as a history of abuse or neglect and substance use in adolescents with different cultural, ethnic, and economic backgrounds living in Denmark, Norway, and Greenland. Internalizing behavior problems were modestly related to CCA use and no differences between samples were found. The results strongly indicate that prevention strategies initiated in childhood with at-risk children as well as social interventions of substance use problems among adolescents should pay close attention to externalizing behavior problems, as they seem to be most strongly associated with CCA use in adolescence.

References

Jensen L (2015) Postcolonial Denmark: beyond the rot of colonialism? Postcolon Stud 18(4):440–452

Connell J (2016) Greenland and the Pacific Islands: an improbable conjunction of development trajectories. Isl Stud J 11(2):465–484

Kraus L, Guttormsson U, Leifman H, Arpa S, Molinaro S (2016) ESPAD Report 2015: results from the European School Survey Project on alcohol and other drugs. Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg

Niclasen BV (2015) Trivsel og sundhed blandt folkesskoleelever i Grønland. SIF’s Grønlandsskrifter, vol 27. Statens Institut for Folkesundhed, København

Pedersen CP, Bjerregaard P, Nielsen NO, Dahl-Petersen IK, Larsen CVL, Olesen I, Budtz CK (2012) Det svære ungdomsliv: Unges trivsel i Grønland 2011—En undersøgelse om de ældste folkeskoleelever [The Difficult Youth Years: Well-being of Youth in Greenland 2011—a survey on lower secondary pupils]. The Danish National Institute of Public Health (NIPH) in Greenland

Skogen JC, Bøe T, Sivertsen B, Hysing M (2018) Use of alcohol, tobacco and illicit drugs among ethnic Norwegian and ethnic minority adolescents in Hordaland county, Norway: the youth@ hordaland-survey. Ethn Health 23(1):43–56

Van Ours JC, Williams J (2009) Why parents worry: initiation into cannabis use by youth and their educational attainment. J Health Econ 28(1):132–142

Leach LS, Butterworth P (2012) The effect of early onset common mental disorders on educational attainment in Australia. Psychiatry Res 199(1):51–57

Wiefferink CH, Peters L, Hoekstra F, Ten Dam G, Buijs GJ, Paulussen TGWM (2006) Clustering of health-related behaviors and their determinants: possible consequences for school health interventions. Prev Sci 7(2):127–149. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-005-0021-2

Farmer RF, Gau JM, Seeley JR, Kosty DB, Sher KJ, Lewinsohn PM (2016) Internalizing and externalizing disorders as predictors of alcohol use disorder onset during three developmental periods. Drug Alcohol Depend 164:38–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.04.021

Farmer RF, Seeley JR, Kosty DB, Gau JM, Duncan SC, Lynskey MT, Lewinsohn PM (2015) Internalizing and externalizing psychopathology as predictors of cannabis use disorder onset during adolescence and early adulthood. Psychol Addict Behav 29(3):541–551. https://doi.org/10.1037/adb0000059

Laukkanen E, Shemeikka S, Notkola I-L, Koivumaa-Honkanen H, Nissinen A (2002) Externalizing and internalizing problems at school as signs of health-damaging behaviour and incipient marginalization. Health Promot Int 17(2):139–146. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/17.2.139

Griffith-Lendering MFH, Huijbregts SCJ, Mooijaart A, Vollebergh WAM, Swaab H (2011) Cannabis use and development of externalizing and internalizing behaviour problems in early adolescence: a TRAILS study. Drug Alcohol Depend 116(1–3):11–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.11.024

Brook JSE, Zhang CP, Brook DWMD (2011) Developmental trajectories of marijuana use from adolescence to adulthood: personal predictors. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 165(1):55

Hayatbakhsh MR, Mcgee TR, Bor W, Najman JM, Jamrozik K, Mamun AA (2008) Child and adolescent externalizing behavior and cannabis use disorders in early adulthood: an Australian prospective birth cohort study. Addict Behav 33(3):422–438. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.10.004

Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Ridder EM (2005) Show me the child at seven II: childhood intelligence and later outcomes in adolescence and young adulthood. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 46(8):850–858. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01472.x

Patrick ME, Schulenberg JE (2013) Prevalence and predictors of adolescent alcohol use and binge drinking in the United States. Alcohol Res 35(2):193–200

Pedersen W, von Soest T (2015) Adolescent alcohol use and binge drinking: an 18-year trend study of prevalence and correlates. Alcohol Alcohol 50(2):219–225. https://doi.org/10.1093/alcalc/agu091

Hinshaw SP (1992) Externalizing behavior problems and academic underachievement in childhood and adolescence: causal relationships and underlying mechanisms. Psychol Bull 111(1):127–155. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.111.1.127

Savolainen J, Mason WA, Bolen JD, Chmelka MB, Hurtig T, Ebeling H, Nordstrom T, Taanila A (2015) The path from childhood behavioural disorders to felony offending: investigating the role of adolescent drinking, peer marginalisation and school failure. Crim Behav Ment Heal 25(5):375–388. https://doi.org/10.1002/cbm.1931

Hayatbakhsh R, Mamun AA, Williams GM, O’Callaghan MJ, Najman JM (2013) Early childhood predictors of early onset of smoking: a birth prospective study. Addict Behav 38(10):2513–2519. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.05.009

Ellickson PL, Tucker JS, Klein DJ (2001) High-risk behaviors associated with early smoking: results from a 5-year follow-up. J Adolesc Health Off Publ Soc Adolesc Med 28(6):465–473

Fischer JA, Najman JM, Williams GM, Clavarino AM (2012) Childhood and adolescent psychopathology and subsequent tobacco smoking in young adults: findings from an Australian birth cohort. Addiction 107(9):1669–1676. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.03846.x

Griffin KW, Botvin GJ, Scheier LM, Doyle MM, Williams C (2003) Common predictors of cigarette smoking, alcohol use, aggression, and delinquency among inner-city minority youth. Addict Behav 28(6):1141–1148

Heron J, Barker ED, Joinson C, Lewis G, Hickman M, Munafo M, Macleod J (2013) Childhood conduct disorder trajectories, prior risk factors and cannabis use at age 16: birth cohort study. Addiction 108(12):2129–2138. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.12268

Lee SS, Humphreys KL, Flory K, Liu R, Glass K (2011) Prospective association of childhood attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and substance use and abuse/dependence: a meta-analytic review. Clin Psychol Rev 31(3):328–341. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2011.01.006

Fergusson DM, Boden JM (2008) Cannabis use and later life outcomes. Addiction 103(6):969–976. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02221.x (discussion 977–968)

Volkow ND, Baler RD, Compton WM, Weiss SR (2014) Adverse health effects of marijuana use. New Engl J Med 370(23):2219–2227. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1402309

Monshouwer K, Van Dorsselaer S, Verdurmen J, Ter Bogt T, De Graaf RON, Vollebergh W (2006) Cannabis use and mental health in secondary school children: findings from a Dutch survey. Br J Psychiatr 188(2):148–153

Miettunen J, Murray GK, Jones PB, Maki P, Ebeling H, Taanila A, Joukamaa M, Savolainen J, Tormanen S, Jarvelin MR, Veijola J, Moilanen I (2014) Longitudinal associations between childhood and adulthood externalizing and internalizing psychopathology and adolescent substance use. Psychol Med 44(8):1727–1738. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291713002328

Oshri A, Rogosch FA, Burnette ML, Cicchetti D (2011) Developmental pathways to adolescent cannabis abuse and dependence: child maltreatment, emerging personality, and internalizing versus externalizing psychopathology. Psychol Addict Behav J Soc Psychol Addict Behav 25(4):634–644. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023151

Pedersen MU, Rømer Thomsen K, Pedersen MM, Hesse M (2016) Mapping risk factors for substance use: introducing the YouthMap12. Addict Behav 23(65):40–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.09.005

King SM, Iacono WG, McGue M (2004) Childhood externalizing and internalizing psychopathology in the prediction of early substance use. Addiction 99(12):1548–1559. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00893.x

Colder CR, Scalco M, Trucco EM, Read JP, Lengua LJ, Wieczorek WF, Hawk LW Jr (2013) Prospective associations of internalizing and externalizing problems and their co-occurrence with early adolescent substance use. J Abnorm Child Psychol 41(4):667–677. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-012-9701-0

Edwards AC, Latendresse SJ, Heron J, Cho SB, Hickman M, Lewis G, Dick DM, Kendler KS (2014) Childhood internalizing symptoms are negatively associated with early adolescent alcohol use. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 38(6):1680–1688. https://doi.org/10.1111/acer.12402

Lynam DR, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Wikström P-OH, Loeber R, Novak S (2000) The interaction between impulsivity and neighborhood context on offending: the effects of impulsivity are stronger in poorer neighborhoods. J Abnorm Psychol (1965) 109(4):563–574

Shin SH, Miller DP, Teicher MH (2013) Exposure to childhood neglect and physical abuse and developmental trajectories of heavy episodic drinking from early adolescence into young adulthood. Drug Alcohol Depend 127(1–3):31–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.06.005

Oshri A, Carlson MW, Kwon JA, Zeichner A, Wickrama KK (2016) Developmental growth trajectories of self-esteem in adolescence: associations with child neglect and drug use and abuse in young adulthood. J Youth Adolesc. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-016-0483-5

Rodham K, Hawton K, Evans E, Weatherall R (2005) Ethnic and gender differences in drinking, smoking and drug taking among adolescents in England: a self-report school-based survey of 15 and 16 year olds. J Adolesc 28(1):63–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2004.07.005

Smith SM, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Goldstein R, Huang B, Grant BF (2006) Race/ethnic differences in the prevalence and co-occurrence of substance use disorders and independent mood and anxiety disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Psychol Med 36(7):987–998

Amey CH, Albrecht SL (1998) Race and ethnic differences in adolescent drug use: the impact of family structure and the quantity and quality of parental interaction. J Drug Issues 28(2):283–298

James WH, Kim GK, Armijo E (2000) The influence of ethnic identity on drug use among ethnic minority adolescents. J Drug Educ 30(3):265–280

Chen P, Jacobson KC (2012) Developmental trajectories of substance use from early adolescence to young adulthood: gender and racial/ethnic differences. J Adolesc Health 50(2):154–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.05.013

Pedersen MU, Villumsen S (2016) The complete YouthMap questionnaire. Centre for Alcohol and Drug Research, Aarhus University, Aarhus

Friedman AS, Terras A, Ôberg D (2001) Euro Adolescent Drug Abuse Diagnosis (Euro-ADAD). European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA), Lisbon

Blacken P, Hendriks V, Pozzi G, Tempesta E, Hartgers C, Koeter M, Fahrner EM, Gsellhofer B, Küfner H, Kokkevi A, Uchtenhagen A (1994) European Addiction Severity Index (EuropASI). European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA), Lisbon

Gray MJ, Litz BT, Hsu JL, Lombardo TW (2004) Psychometric properties of the life events checklist. Assessment 11(4):330–341. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191104269954

EMCDDA (2012) Prevalence of daily cannabis use in the European Union and Norway. Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg. https://doi.org/10.2810/73754

Agrawal A, Grant JD, Waldron M, Duncan AE, Scherrer JF, Lynskey MT, Madden PAF, Bucholz KK, Heath AC (2006) Risk for initiation of substance use as a function of age of onset of cigarette, alcohol and cannabis use: findings in a Midwestern female twin cohort. Prev Med Int J Devot Pract Theory 43(2):125–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2006.03.022

Hammond D, Fong GT, Zanna MP, Thrasher JF, Borland R (2006) Tobacco denormalization and industry beliefs among smokers from four countries. Am J Prev Med 31(3):225–232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2006.04.004

Doran N, McChargue D, Spring B, VanderVeen J, Cook JW, Richmond M (2006) Effect of nicotine on negative affect among more impulsive smokers. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol 14(3):287–295. https://doi.org/10.1037/1064-1297.14.3.287

Gardner TW, Dishion TJ, Posner MI (2006) Attention and adolescent tobacco use: a potential self-regulatory dynamic underlying nicotine addiction. Addict Behav 31(3):531–536

Griesler PC, Hu M, Schaffran C, Kandel DB (2011) Comorbid psychiatric disorders and nicotine dependence in adolescence. Addiction 106(5):1010–1020. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03403.x

Levin ED, Conners CK, Silva D, Canu W, March J (2001) Effects of chronic nicotine and methylphenidate in adults with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol 9(1):83–90

Potter AS, Newhouse PA (2004) Effects of acute nicotine administration on behavioral inhibition in adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Psychopharmacology 176(2):182–194

van Lier PA, Huizink A, Vuijk P (2011) The role of friends’ disruptive behavior in the development of children’s tobacco experimentation: results from a preventive intervention study. J Abnorm Child Psychol 39(1):45–57. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-010-9446-6

Skogen JC, Sivertsen B, Lundervold AJ, Stormark KM, Jakobsen R, Hysing M (2014) Alcohol and drug use among adolescents: and the co-occurrence of mental health problems. Ung@hordaland, a population-based study. BMJ Open 4(9):e005357. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005357

Scalco MD, Colder CR, Hawk LW, Read JP, Wieczorek WF, Lengua LJ (2014) Internalizing and externalizing problem behavior and early adolescent substance use: a test of a latent variable interaction and conditional indirect effects. Psychol Addict Behav 28(3):828–840. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035805

Dahl-Petersen IK, Larsen CVL, Nielsen NO, Jørgensen ME, Bjerregaard P (2016) Befolkningsundersøgelsen i Grønland 2014, Kalaallit Nunaanni Innuttaasut Peqqissusaannik Misissuisitsineq 2014 [The population survey in Greenland, 2014]. National Institute of Public Health’s Greenland works, vol 28. National Institute of Public Health, University of Southern Denmark, Copenhagen

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical standards

The manuscript does not contain clinical studies or patient data. All participants gave their consent and the surveys were approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency just as all confidentiality and privacy requirements were met.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest. This work was funded by a block Grant from the Danish Ministry for Social Affairs and the Interior (MUP, KRT, and SJ), and the Health Ministry of Western Norway (OH). JCS did not receive any specific funding for this project. The funding sources had no role in the writing of the manuscript or the decision to submit it for publication.

Appendix 1

Appendix 1

YouthMap12

With filter questions (survey version)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pedersen, M.U., Thomsen, K.R., Heradstveit, O. et al. Externalizing behavior problems are related to substance use in adolescents across six samples from Nordic countries. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 27, 1551–1561 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-018-1148-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-018-1148-6