Abstract

Objectives

Limited long-term data are available when comparing the esthetic outcomes of coronally advanced flap (CAF) with or without a connective tissue graft (CTG). The aim of this study was to compare the 4-year esthetic outcomes of CAF vs CAF + CTG for the treatment of isolated maxillary gingival recessions.

Material and methods

Forty-eight patients were randomly assigned for treatment either with CAF (control; N = 24) or to CAF + CTG (test group; N = 24). Patients were followed after the surgery until the final evaluation. A professional esthetic evaluation was performed using the Root coverage Esthetic Score (RES). Recession reduction, mean root coverage, and complete root coverage were also evaluated.

Results

Forty-two patients completed the study at the 4-year recall. A significant recession reduction was evident at 4 years, without significant intergroup differences. The CAF group showed a statistically significant higher final RES compared with the CAF + CTG group (9.14 ± 1.08 vs 7.25 ± 1.29, respectively, p < 0.001). Regarding the individual components of RES, gingival margin and marginal tissue contour were significantly higher in the CAF group compared with that in the CAF + CTG group.

Conclusions

CAF presented with a significantly higher overall esthetic score than CAF + CTG, and in the individual RES components of marginal tissue contour and gingival margin after 4 years.

Clinical relevance

CAF without the addition of CTG provided higher esthetic outcomes for the treatment of isolated gingival recessions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Gingival recession (GR) is defined as the apical shift of the gingival margin with respect to the cemento-enamel junction (CEJ) with the concomitant exposure of a portion of the root surface to the oral environment [1]. GR represents a common clinical finding [2, 3], with a prevalence that according to Rios et al. can be up to 99.7% [4]. The high prevalence of these mucogingival defects can be attributed to a large variety of predisposing and precipitating factors, including traumatic toothbrushing, periodontal disease, tooth malposition, frenum pull, iatrogenic trauma, and orthodontic treatment among others [1, 5].

Root coverage procedures have been shown to be effective in treating GRs, with connective tissue graft (CTG) demonstrating the highest results in terms of mean—and complete—root coverage (mRC, CRC) [6,7,8,9]. Nevertheless, it should be noted that among the goals of root coverage procedures, improving patients’ esthetic outcomes and obtaining their satisfaction if not the main goal of the treatment are indeed among the top priorities [10,11,12,13].

Recently, several authors have investigated the long-term behavior of the gingival margin following root coverage procedures with different techniques [14,15,16,17,18]. It was concluded that CTG-based techniques were effective in maintaining the stability of the gingival margin, while the other approaches, including coronally advanced flap (CAF) alone, guided tissue regeneration or the use of extracellular matrices had a significant recession recurrence over time [6, 14, 19]. Nevertheless, among the limitations of long-term follow-up studies, it should be mentioned that several patients may have discontinued or quitted the maintenance program, the examiner may be different, and that the esthetic evaluation is often missing. The root coverage esthetic score (RES) introduced by Cairo et al. [11] has been shown to be predictable has been shown to be a reliable tool for assessing the esthetic outcomes of root coverage procedures, not only among experts [20] but also among operators with different levels of periodontal experience [21]. This score is based on the evaluation of five parameters, including the level of the gingival margin (GM), marginal tissue contour (MTC), soft tissue texture (STT), alignment of the mucogingival junction (MGJ), and gingival color (GC) [11]. Few studies have investigated the RES score of root coverage procedure with more than 1 year of follow-up [22]. Similarly, whether the RES scores are affected by time is still unknown.

Therefore, the aim of the present manuscript is to report on the esthetic outcome of 4-year randomized clinical trial comparing the CAF with and without the addition of a CTG.

Materials and methods

Ethical consideration and study design

This clinical study was approved by the Ethics on Research Committee of the Faculty of Dentistry at the Científica del Sur University and was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975 as revised in the year 2000. The subjects participating in the study were volunteers and provided signed informed consent. In addition, the study design was prepared according to the CONSORT statement. All researchers followed the guidelines of good clinical practice.

The study was designed as a parallel-arm randomized controlled clinical trial. Forty-four systemically healthy, non-smoking subjects, 18 to 60 years old (mean age of 46.86 for the control group and 44.6 for the experimental group), with individual recessions on incisors, canines, and premolars, were consecutively enrolled and randomly treated with either a coronally advanced flap (CAF) or with a coronally advanced flap + connective tissue graft (CAF + CTG). The participants were selected among patients from the Department of Periodontology, School of Dentistry, Universidad Científica del Sur, Lima. Their chief complaint of undergoing the procedure had mainly been esthetics followed by some dental hypersensitivity. Every patient received detailed information about the proposed therapy and provided informed consent.

Inclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria for the present study were as follows: systemically healthy non-smoking patients, ≥ 18 years old, presenting with one isolated maxillary GR classified as recession type 1 (RT1) [23], full-mouth plaque, and bleeding score ≤ 15%. Medically compromised patients, pregnant, smoking, untreated periodontal disease, previous periodontal plastic surgery at the experimental sites, GRs on molars, and recession types 2 and 3 [23] were considered as exclusion criteria.

Pre-surgical procedures

Eligible patients received a session of prophylaxis, including oral hygiene instruction aimed at eliminating possible traumatic toothbrushing habits at least 1 month before the surgery. However, surgical intervention was not scheduled until the patient could demonstrate an adequate standard of plaque control.

Intervention

All surgical procedures were performed by a single operator (G.M.A) with more than 20 years of experience in periodontal plastic surgery. Teeth presenting with a non-carious cervical lesion or not identifiable CEJ were treated prior to the surgery with composite filling to reconstruct the CEJ using adjacent and contralateral unrestored teeth as references [24, 25]. The composite restoration was extended 1 mm apical to the ideal CEJ level [24].

CAF alone with or without CTG was executed as previously described in the literature [26, 27]. Patients were randomly assigned to either test (CAF + CTG) or control (CAF alone) group. Briefly, after local anesthesia, root surfaces were gently planed and an intrasulcular incision was made on the buccal aspect of the involved tooth extending mesio-distally to dissect the buccal aspect of the adjacent papillae while avoiding the gingival margin of the adjacent teeth. Two oblique releasing incisions were carried out from the mesial and distal extremities of the horizontal incisions beyond the mucogingival junction. A trapezoidal full-thickness flap was raised in direction of the mucogingival junction, then a partial thickness dissection was made apically towards the marginal bone crest leaving the underline periosteum in place. The papillae adjacent to the involved tooth were de-epithelialized, then the flap was coronally positioned 1–2 mm above the CEJ and sutured [28].

For the test group, the same procedure was performed with the addition of a CTG harvesting from the palate, as described by Langer and Langer [29]. The palatal wound was sutured with a cross-suture. Flaps were sutured with 5–0 Nylon suturesFootnote 1 or with 5-0 Vicryl suturesFootnote 2.

Post-surgical care/follow-up

After surgery patients were instructed to discontinue toothbrushing, the area where the surgery was performed for 3 weeks; sutures were removed after 2 weeks. Three weeks after the surgery, the patients resumed mechanical tooth cleaning of the treated areas using a soft toothbrush and careful roll technique. Patients were planned for recall appointments at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months, and a final follow-up of 4 years following the surgery for evaluating the long-term outcomes of the results, and the esthetics. During the recall appointment, they were reinforced on oral hygiene instructions, supragingival plaque elimination.

Clinical measurements

For all the patients in this study, their demographic details, age, and sex were recorded. The following clinical measurements were performed at baseline and at 1, 3, 6, 12, and 48 months after the surgery: pocket depth (PD) and recession depth in the mid-facial area of the tooth to treat, from the CEJ to the gingival margin (REC). For teeth presenting with not identifiable CEJ at baseline, REC was measured from the gingival margin to the restored CEJ [24].

At the final recall (4-year time point), the esthetic outcomes were assessed using the Root coverage Esthetic Score (RES) [11], by evaluating the following five parameters: gingival margin (GM), marginal tissue contour (MTC), soft tissue texture (STT), mucogingival alignment (MGJ), and gingival color (GC).

Study outcomes

The outcome of the study was to compare the esthetic results of CAF vs CAF + CTG after 4 years and to evaluate which parameters affect the final esthetic score in both groups.

Secondary outcomes included recession reduction, mean root coverage (mRC), and complete root coverage (CRC).

Sample size

The sample size was calculated using a statistical softwareFootnote 3 based on an alpha error of 0.05 and a power of 0.95. For variability, a previous publication was used as a reference [27]. The minimum clinically significant value was considered as 0.5 mm. It was found that the expected effect of the difference in results in the reduction of recessions was 1.26 mm between the groups and that a minimum of 15 patients per group was needed. However, in order to account for possible dropouts over the follow-up period of 4 years, it was decided to increase the sample size to 48.

Randomization, allocation concealment, and masking of the examiner

Each patient was randomly assigned to the test or control group using a computer-generated random list. All the clinical measures and pictures of each patient were sent to an independent examiner that was blinded to the performed treatments.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis of clinical parameters (i.e., REC 1, REC 2, MG, MTC, and STT) was carried out to compare the baseline values with the 1, 3, 6, and 12-month post-operative values using the SSPSFootnote 4 with a power of 80% and a confidence interval (CI) of 99%. Descriptive statistic was used to present the gathered data. The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to test data normality. The Student t test was used for the comparison of continuous data among different groups at each time point (unpaired t tests) and among different time points in the same groups (paired t tests), as well as the Mann-Whitney U for comparison of ordinal/continuous data among different groups.

Results

Overall, 80 patients were screened for eligibility between April and August 2015. Among them, 32 declined to participate (Fig. 1). As a result, 48 patients were enrolled in the study and received treatment. Six patients (4 in the test group and 2 in the control group) were lost during the follow-up period. The reasons for dropout were as follows: patients moving away, changes in conditions such as pregnancy, and being out of reach. Therefore, 42 sites from 42 patients (22 in the control and 20 in the test group) were considered in our analysis. The mean age in the control group was 46.86 ± 9.52 years, while in the experimental group was 44.6 ± 11.93 years. Four canines and 18 premolars were treated in the CAF group, while 2 incisors, 5 canines, and premolars were included in the CAF + CTG group. Table 1 depicts the patient characteristics at baseline.

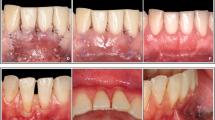

Recession depth at baseline was 3.45 ± 1.01 mm for the control, and 3.2 ± 0.77 mm for the test group, without statistically significant differences between the two groups. The recession depth at the 4-year recall was 0.72 ± 1.12 (mRC of 79.1%) for the patients that received CAF alone and 0.6 ± 0.82 mm (mRC 81.3%) for the patients who received CAF + CTG, without any statistical differences between the two techniques. Both groups showed a significant improvement in recession depth from baseline to the 4-year recall (p < 0.001). The CAF-alone group showed a statistically significant higher CRC than CAF + CTG (Table 2).

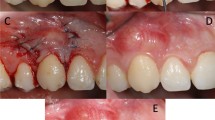

When the esthetic outcomes at 4 years were compared, patients who received CAF alone showed significantly higher RES scores than patients assigned to CAF + CTG (9.14 ± 1.08 vs 7.25 ± 1.29, respectively, p < 0.001) (Fig. 2). In addition, the control group achieved significantly higher scores for the GM and MTC parameters compared with the test group (Table 3). In particular, no patients in the CAF group were rated 0 for the MTC, while 65% of the patients in the CAF + CTG group showed a MTC of zero. Logistic binary regression showed that patients with an adequate marginal tissue contour (MTC = 1) had an odds ratio of 15.75 to achieve a better RES score than those who received a score of 0 for this parameter in the RES evaluation (p = 0.003, CI [2.96–95.61]) and also that the technique (either CAF or CAF + CTG) was significantly associated with the final RES (p = 0.019, CI [0.008–0.642]).

The multiple linear regression model showed that the RES could be estimated by some variables, such as GM, MTC, and MGJ. The model was statistically significant with a R2 adjusted to 63% and p < 0.001 (Table 4).

Discussion

One of the main indications for the treatment of GRs is patient esthetic concern [1, 22, 30]. It has been shown that root coverage procedures are effective in improving esthetics, from both clinician and patient perspectives [12, 31, 32].

Several systems have been used over the years for evaluating the esthetic outcomes of root coverage procedures, including the visual analog scale (VAS), the pink esthetic score, or more complex system evaluating other factors [11, 33,34,35,36,37,38]. Among them, the RES system that has been introduced by Cairo et al. [11] has been shown to be a valid tool for assessing the esthetic outcomes of root coverage procedure not only among expert periodontists but also among individuals with different expertise [20, 21]. Since its introduction, the RES system has been increasingly used in clinical studies for comparing the esthetic outcome of root coverage techniques. Nevertheless, most of the studies comparing the RES outcomes of different root coverage techniques have a mean period of observation of 6 or 12 months only and limited data regarding the esthetic outcomes following the treatment of gingival recessions are available with longer follow-up.

Interestingly, while our study did not find differences among the two groups in terms of mean root coverage, it was shown that the CAF group had a significantly higher RES than the CAF + CTG group (9.14 ± 1.08 vs 7.25 ± 1.29, respectively) after 4 years. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first randomized clinical trial comparing the RES outcomes of a single recession treated with CAF or CAF + CTG with a follow-up of > 3 years.

It has been demonstrated that CAF + CTG should be considered the gold standard treatment in terms of mean and complete root coverage [6, 39,40,41]. Therefore, bearing in mind that the amount of root coverage achieved largely affect the final RES (6 points out of 10), it is not surprising that a review by Cairo et al. concluded that CAF + CTG had a better probability to achieve higher esthetic outcomes than CAF alone [12]. Nevertheless, there are some clinical scenarios in which it has been suggested that adding a CTG may not be beneficial. In a randomized clinical trial, it was observed that CAF + CTG provided superior outcomes than CAF alone only when the initial gingival thickness was ≤ 0.8 mm [42]. In line with this finding, Stefanini and coworkers proposed a selective use of CTG only for sites presenting with gingival thickness < 1 mm and keratinized tissue width < 1 mm [43]. Interestingly, a histological study showed that sites with a thick gingival phenotype had a significantly thicker connective tissue layer than sites with thin phenotype [44], suggesting that adding a CTG in sites with an already thick connective tissue layer should be considered an “overtreatment” [45]. Indeed, the final esthetic outcomes may be compromised if a CTG is added in a site with an already thick gingival phenotype, as recently demonstrated by Cairo and coworkers who observed that CAF alone achieved better final RES scores for baseline gingival thickness > 0.82 mm [46]. Therefore, it is not surprising that “graftless” root coverage procedures have been suggested in patients with a thick or very thick gingival phenotype [47,48,49]. The increased post-operative morbidity [50, 51] and risk for complications [52, 53] related to palatal harvesting suggest using CTG only when indicated [45].

Another interesting finding from our analysis is related to the MTC. CAF alone achieved a MTC of 1 in all the cases, while CAF + CTG achieved a significantly lower MTC (0.35 ± 0.49). It can be speculated that the addition of a graft, especially when in presence of a thick gingiva at baseline, may result in a bulky and irregular gingival margin that does not follow the CEJ, while the coronal advancement of the flap without any graft addition may have more chance to heal with a scalloped gingival margin that follows the CEJ. In line with our speculations, Pelekos and coworkers found that CAF + CTG achieved significantly lower MTC and STT than CAF + xenogeneic collagen matrix [54]. The authors suggested to keep in mind that good performance of CTG in terms of the amount of root coverage may mask subtler differences in the esthetic outcomes and that a more natural appearance should outweigh the esthetic benefits of better root coverage in selected cases [54].

Interestingly, when adjusted for the two types of interventions, the logistic binary regression showed that patients with an adequate marginal tissue contour (MTC = 1) had an odds ratio of 15.75 to achieve a better RES score than those who received a score of 0 for this parameter in the RES evaluation. In addition, our regression model also found that the final RES was positively affected by the technique (CAF alone), GM, MTC, and MGJ. Further studies are needed to validate this finding.

The stability of the surgical outcomes over time has progressively gained interest in the scientific community [6, 7, 17]. It has been shown that CAF alone has a tendency to relapse over time [6, 15, 17, 55, 56]. In a 12-year follow-up study, Barootchi and coworkers analyzed sites that were treated with CAF + CTG and adjacent sites that received CAF only [15]. While a certain tendency towards the relapse of the gingival margin was observed between 6 months and 12 years, the reduction in the amount of root coverage was significantly greater for sites that did not receive a graft (mRC reduction of 34.12% vs 16.52%, respectively). Among the predictors for the stability of the gingival margin in the long term, it was found that keratinized tissue width at baseline and at 6 months could play a key role [15]. The overall RES for sites that received a CTG was 7.42 and 7.62 (for CTG with and without an epithelial collar, respectively), while adjacent recessions that did not receive a graft but were treated with CAF only had an average RES of 6.45 after 12 years [15].

Similarly, another long-term study concluded that not only the amount of keratinized tissue width but also gingival thickness at 6 months (if ≥ 1.2 mm) was a predictor for the stability of the gingival margin [14]. The importance of gingival/mucosal thickness and its implications have been progressively highlighted in recent years [14, 15, 57]. The RES at 12 years for CAF + acellular dermal matrix and for tunnel + acellular dermal matrix was 7.01 and 6.93, respectively. The significant relapse of the gingival margin observed in both groups can explain the lower RES outcome compared with that in our study.

Other factors, such as study population, patient maintenance protocol, and motivation have been suggested to play a role in the incidence of recession relapse over time [6, 58].

The reason for a similar recession reduction at 4 years between CAF and CAF + CTG in our study (mRC 79.1% vs 81.3%, respectively) is open to speculation. It is likely that all the above-mentioned factors had an impact on the stability of the results over the 4 years. Indeed, when comparing our results with the literature, Pini Prato et al. showed a mRC of approximately 65% for sites treated with CAF alone [55] and 81% for sites that received CAF + CTG after 5 years [16]. Kuis and coworkers found a mRC similar to our result for CAF alone after 5 years (82.5%), while their mRC in the CAF + CTG group was 92.77% [59]. A 5-year randomized clinical trial by Zucchelli and coworkers reported mRC of 90% and 97% for multiple recessions treated with CAF and CAF + CTG, respectively [60]. The authors performed the esthetic evaluation by having patients and a periodontist rating the final outcome with a VAS. Interestingly, CAF received higher scores at 1 and 5 years by the patients, although these differences were not statistically significant. The evaluation from a periodontist revealed a significantly higher color match for CAF alone, while a better contour was observed in the CAF + CTG group [60]. Nevertheless, the different conditions (single vs multiple GRs) and the different esthetic evaluation systems (RES vs VAS) do not allow for a direct comparison with our study.

Among the limitation of the present study, it should be mentioned that the randomization of the subjects presenting with GRs without taking into account the gingival phenotype [49] and the number of drop outs over the 4 year follow-up could have played a role in the clinical and esthetic results. It can be speculated that patients with thick phenotype in the CAF + CTG group have contributed to the lower esthetic outcomes. In addition, although all the patients were enrolled in a strict maintenance program for all the studies, differences in patients’ compliance could have affected the outcomes. Lastly, only maxillary gingival recessions were treated, and this may have played a role in the root coverage outcomes [9, 61] and on the overall RES [20, 22].

Therefore, readers have to take these aspects into consideration when interpreting our results.

Conclusions

Within its limitations, the present study concluded that CAF with or without CTG obtained a significant recession reduction after 4 years, with CAF alone showing a higher esthetic score and marginal tissue contour than CAF + CTG.

Notes

Ethicon, Johnson & Johnson, USA

Ethicon, Johnson & Johnson, USA

Version 23.0, SSPS, Chicago, IL

References

Cortellini P, Bissada NF (2018) Mucogingival conditions in the natural dentition: narrative review, case definitions, and diagnostic considerations. J Periodontol 89(Suppl 1):S204–S213. https://doi.org/10.1002/JPER.16-0671

Serino G, Wennstrom JL, Lindhe J, Eneroth L (1994) The prevalence and distribution of gingival recession in subjects with a high standard of oral hygiene. J Clin Periodontol 21(1):57–63

Romandini M, Soldini MC, Montero E, Sanz M (2020) Epidemiology of mid-buccal gingival recessions in NHANES according to the 2018 World Workshop Classification System. J Clin Periodontol. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpe.13353

Rios FS, Costa RS, Moura MS, Jardim JJ, Maltz M, Haas AN (2014) Estimates and multivariable risk assessment of gingival recession in the population of adults from Porto Alegre, Brazil. J Clin Periodontol 41(11):1098–1107. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpe.12303

Zucchelli G, Mounssif I (2015) Periodontal plastic surgery. Periodontol 68(1):333–368. https://doi.org/10.1111/prd.12059

Tavelli L, Barootchi S, Cairo F, Rasperini G, Shedden K, Wang HL (2019) The effect of time on root coverage outcomes: a network meta-analysis. J Dent Res 98(11):1195–1203. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022034519867071

Zucchelli G, Tavelli L, McGuire MK, Rasperini G, Feinberg SE, Wang HL, Giannobile WV (2020) Autogenous soft tissue grafting for periodontal and peri-implant plastic surgical reconstruction. J Periodontol 91(1):9–16. https://doi.org/10.1002/JPER.19-0350

Tavelli L, Barootchi S, Nguyen TVN, Tattan M, Ravida A, Wang HL (2018) Efficacy of tunnel technique in the treatment of localized and multiple gingival recessions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Periodontol 89(9):1075–1090. https://doi.org/10.1002/JPER.18-0066

Zucchelli G, Tavelli L, Barootchi S, Stefanini M, Rasperini G, Valles C, Nart J, Wang HL (2019) The influence of tooth location on the outcomes of multiple adjacent gingival recessions treated with coronally advanced flap: a multicenter re-analysis study. J Periodontol 90(11):1244–1251. https://doi.org/10.1002/JPER.18-0732

Stefanini M, Jepsen K, de Sanctis M, Baldini N, Greven B, Heinz B, Wennstrom J, Cassel B, Vignoletti F, Sanz M, Jepsen S, Zucchelli G (2016) Patient-reported outcomes and aesthetic evaluation of root coverage procedures: a 12-month follow-up of a randomized controlled clinical trial. J Clin Periodontol 43(12):1132–1141. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpe.12626

Cairo F, Rotundo R, Miller PD, Pini Prato GP (2009) Root coverage esthetic score: a system to evaluate the esthetic outcome of the treatment of gingival recession through evaluation of clinical cases. J Periodontol 80(4):705–710. https://doi.org/10.1902/jop.2009.080565

Cairo F, Pagliaro U, Buti J, Baccini M, Graziani F, Tonelli P, Pagavino G, Tonetti MS (2016) Root coverage procedures improve patient aesthetics. A systematic review and Bayesian network meta-analysis. J Clin Periodontol 43(11):965–975. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpe.12603

Tavelli L, Barootchi S, Greenwell H, Wang HL (2019) Is a soft tissue graft harvested from the maxillary tuberosity the approach of choice in an isolated site? J Periodontol 90(8):821–825. https://doi.org/10.1002/JPER.18-0615

Tavelli L, Barootchi S, Di Gianfilippo R, Modarressi M, Cairo F, Rasperini G, Wang HL (2019) Acellular dermal matrix and coronally advanced flap or tunnel technique in the treatment of multiple adjacent gingival recessions. A 12-year follow-up from a randomized clinical trial. J Clin Periodontol 46(9):937–948. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpe.13163

Barootchi S, Tavelli L, Di Gianfilippo R, Byun HY, Oh TJ, Barbato L, Cairo F, Wang HL (2019) Long term assessment of root coverage stability using connective tissue graft with or without an epithelial collar for gingival recession treatment. A 12-year follow-up from a randomized clinical trial. J Clin Periodontol 46(11):1124–1133. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpe.13187

Pini Prato GP, Franceschi D, Cortellini P, Chambrone L (2018) Long-term evaluation (20 years) of the outcomes of subepithelial connective tissue graft plus coronally advanced flap in the treatment of maxillary single recession-type defects. J Periodontol 89(11):1290–1299. https://doi.org/10.1002/JPER.17-0619

Rasperini G, Acunzo R, Pellegrini G, Pagni G, Tonetti M, Pini Prato GP, Cortellini P (2018) Predictor factors for long-term outcomes stability of coronally advanced flap with or without connective tissue graft in the treatment of single maxillary gingival recessions: 9 years results of a randomized controlled clinical trial. J Clin Periodontol 45(9):1107–1117. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpe.12932

Barootchi S, Tavelli L, Gianfilippo RD, Eber R, Stefanini M, Zucchelli G, Wang HL (2020) Acellular dermal matrix for root coverage procedures. 9-year assessment of treated isolated gingival recessions and their adjacent untreated sites. J Periodontol. https://doi.org/10.1002/JPER.20-0310

Tavelli L, McGuire MK, Zucchelli G, Rasperini G, Feinberg SE, Wang HL, Giannobile WV (2020) Extracellular matrix-based scaffolding technologies for periodontal and peri-implant soft tissue regeneration. J Periodontol 91(1):17–25. https://doi.org/10.1002/JPER.19-0351

Cairo F, Nieri M, Cattabriga M, Cortellini P, De Paoli S, De Sanctis M, Fonzar A, Francetti L, Merli M, Rasperini G, Silvestri M, Trombelli L, Zucchelli G, Pini-Prato GP (2010) Root coverage esthetic score after treatment of gingival recession: an interrater agreement multicenter study. J Periodontol 81(12):1752–1758. https://doi.org/10.1902/jop.2010.100278

Isaia F, Gyurko R, Roomian TC, Hawley CE (2018) The root coverage esthetic score: intra-examiner reliability among dental students and dental faculty. J Periodontol 89(7):833–839. https://doi.org/10.1002/JPER.17-0556

Cairo F, Barootchi S, Tavelli L, Barbato L, Wang HL, Rasperini G, Graziani F, Tonetti M (2020) Esthetic- and patient-related outcomes following root coverage procedures: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. J Clin Periodontol. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpe.13346

Cairo F, Nieri M, Cincinelli S, Mervelt J, Pagliaro U (2011) The interproximal clinical attachment level to classify gingival recessions and predict root coverage outcomes: an explorative and reliability study. J Clin Periodontol 38(7):661–666. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-051X.2011.01732.x

Cairo F, Pini-Prato GP (2010) A technique to identify and reconstruct the cementoenamel junction level using combined periodontal and restorative treatment of gingival recession. A prospective clinical study. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent 30(6):573–581

Zucchelli G, Gori G, Mele M, Stefanini M, Mazzotti C, Marzadori M, Montebugnoli L, De Sanctis M (2011) Non-carious cervical lesions associated with gingival recessions: a decision-making process. J Periodontol 82(12):1713–1724. https://doi.org/10.1902/jop.2011.110080

de Sanctis M, Zucchelli G (2007) Coronally advanced flap: a modified surgical approach for isolated recession-type defects: three-year results. J Clin Periodontol 34(3):262–268. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-051X.2006.01039.x

Cairo F, Cortellini P, Tonetti M, Nieri M, Mervelt J, Cincinelli S, Pini-Prato G (2012) Coronally advanced flap with and without connective tissue graft for the treatment of single maxillary gingival recession with loss of inter-dental attachment. A randomized controlled clinical trial. J Clin Periodontol 39(8):760–768. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-051X.2012.01903.x

Tavelli L, Barootchi S, Ravida A, Suarez-Lopez Del Amo F, Rasperini G, Wang HL (2019) Influence of suturing technique on marginal flap stability following coronally advanced flap: a cadaver study. Clin Oral Investig 23(4):1641–1651. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00784-018-2597-5

Langer B, Langer L (1985) Subepithelial connective tissue graft technique for root coverage. J Periodontol 56(12):715–720. https://doi.org/10.1902/jop.1985.56.12.715

Nieri M, Pini Prato GP, Giani M, Magnani N, Pagliaro U, Rotundo R (2013) Patient perceptions of buccal gingival recessions and requests for treatment. J Clin Periodontol 40(7):707–712. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpe.12114

Sangiorgio JPM, Neves F, Rocha Dos Santos M, Franca-Grohmann IL, Casarin RCV, Casati MZ, Santamaria MP, Sallum EA (2017) Xenogenous collagen matrix and/or enamel matrix derivative for treatment of localized gingival recessions: a randomized clinical trial. Part I: Clinical Outcomes. J Periodontol 88(12):1309–1318. https://doi.org/10.1902/jop.2017.170126

Jepsen K, Jepsen S, Zucchelli G, Stefanini M, de Sanctis M, Baldini N, Greven B, Heinz B, Wennstrom J, Cassel B, Vignoletti F, Sanz M (2013) Treatment of gingival recession defects with a coronally advanced flap and a xenogeneic collagen matrix: a multicenter randomized clinical trial. J Clin Periodontol 40(1):82–89. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpe.12019

Kerner S, Katsahian S, Sarfati A, Korngold S, Jakmakjian S, Tavernier B, Valet F, Bouchard P (2009) A comparison of methods of aesthetic assessment in root coverage procedures. J Clin Periodontol 36(1):80–87. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-051X.2008.01348.x

Aichelmann-Reidy ME, Yukna RA, Evans GH, Nasr HF, Mayer ET (2001) Clinical evaluation of acellular allograft dermis for the treatment of human gingival recession. J Periodontol 72(8):998–1005. https://doi.org/10.1902/jop.2001.72.8.998

Wang HL, Bunyaratavej P, Labadie M, Shyr Y, MacNeil RL (2001) Comparison of 2 clinical techniques for treatment of gingival recession. J Periodontol 72(10):1301–1311. https://doi.org/10.1902/jop.2001.72.10.1301

Zucchelli G, Marzadori M, Mele M, Stefanini M, Montebugnoli L (2012) Root coverage in molar teeth: a comparative controlled randomized clinical trial. J Clin Periodontol 39(11):1082–1088. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpe.12002

Salhi L, Lecloux G, Seidel L, Rompen E, Lambert F (2014) Coronally advanced flap versus the pouch technique combined with a connective tissue graft to treat Miller’s class I gingival recession: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Periodontol 41(4):387–395. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpe.12207

Stefanini M, Mounssif I, Barootchi S, Tavelli L, Wang HL, Zucchelli G (2020) An exploratory clinical study evaluating safety and performance of a volume-stable collagen matrix with coronally advanced flap for single gingival recession treatment. Clin Oral Investig 24(9):3181–3191. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00784-019-03192-5

Cairo F, Nieri M, Pagliaro U (2014) Efficacy of periodontal plastic surgery procedures in the treatment of localized facial gingival recessions. A systematic review. J Clin Periodontol 41(Suppl 15):S44–S62. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpe.12182

Graziani F, Gennai S, Roldan S, Discepoli N, Buti J, Madianos P, Herrera D (2014) Efficacy of periodontal plastic procedures in the treatment of multiple gingival recessions. J Clin Periodontol 41(Suppl 15):S63–S76. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpe.12172

Chambrone L, Tatakis DN (2015) Periodontal soft tissue root coverage procedures: a systematic review from the AAP Regeneration Workshop. J Periodontol 86(2 Suppl):S8–S51. https://doi.org/10.1902/jop.2015.130674

Cairo F, Cortellini P, Pilloni A, Nieri M, Cincinelli S, Amunni F, Pagavino G, Tonetti MS (2016) Clinical efficacy of coronally advanced flap with or without connective tissue graft for the treatment of multiple adjacent gingival recessions in the aesthetic area: a randomized controlled clinical trial. J Clin Periodontol 43(10):849–856. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpe.12590

Stefanini M, Zucchelli G, Marzadori M, de Sanctis M (2018) Coronally advanced flap with site-specific application of connective tissue graft for the treatment of multiple adjacent gingival recessions: a 3-year follow-up case series. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent 38(1):25–33. https://doi.org/10.11607/prd.3438

Goncalves Motta SH, Ferreira Camacho MP, Quintela DC, Santana RB (2017) Relationship between clinical and histologic periodontal biotypes in humans. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent 37(5):737–741. https://doi.org/10.11607/prd.2501

Chambrone L, Pini Prato GP (2019) Clinical insights about the evolution of root coverage procedures: the flap, the graft, and the surgery. J Periodontol 90(1):9–15. https://doi.org/10.1002/JPER.18-0281

Cairo F, Cortellini P, Nieri M, Pilloni A, Barbato L, Pagavino G, Tonetti M (2020) Coronally advanced flap and composite restoration of the enamel with or without connective tissue graft for the treatment of single maxillary gingival recession with non-carious cervical lesion. A randomized controlled clinical trial. J Clin Periodontol 47(3):362–371. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpe.13229

Rasperini G, Codari M, Limiroli E, Acunzo R, Tavelli L, Levickiene AZ (2019) Graftless tunnel technique for the treatment of multiple gingival recessions in sites with thick or very thick biotype: a prospective case series. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent 39(6):e203–e210. https://doi.org/10.11607/prd.4134

Rasperini G, Codari M, Paroni L, Aslan S, Limiroli E, Solis-Moreno C, Suckiel-Papior K, Tavelli L, Acunzo R (2020) The influence of gingival phenotype on the outcomes of coronally advanced flap: a prospective multicenter study. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent 40(1):e27–e34. https://doi.org/10.11607/prd.4272

Barootchi S, Tavelli L, Zucchelli G, Giannobile WV, Wang HL (2020) Gingival phenotype modification therapies on natural teeth: a network meta-analysis. J Periodontol. https://doi.org/10.1002/JPER.19-0715

Tavelli L, Ravida A, Saleh MHA, Maska B, Del Amo FS, Rasperini G, Wang HL (2019) Pain perception following epithelialized gingival graft harvesting: a randomized clinical trial. Clin Oral Investig 23(1):459–468. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00784-018-2455-5

Tavelli L, Asa’ad F, Acunzo R, Pagni G, Consonni D, Rasperini G (2018) Minimizing patient morbidity following palatal gingival harvesting: a randomized controlled clinical study. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent 38(6):e127–e134. https://doi.org/10.11607/prd.3581

Tavelli L, Barootchi S, Namazi SS, Chan HL, Brzezinski D, Danciu T, Wang HL (2020) The influence of palatal harvesting technique on the donor site vascular injury: a split-mouth comparative cadaver study. J Periodontol 91(1):83–92. https://doi.org/10.1002/JPER.19-0073

Tavelli L, Barootchi S, Ravida A, Oh TJ, Wang HL (2019) What is the safety zone for palatal soft tissue graft harvesting based on the locations of the greater palatine artery and foramen? A Systematic Review. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 77(2):271 e271–271 e279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joms.2018.10.002

Pelekos G, Lu JZ, Ho DKL, Graziani F, Cairo F, Cortellini P, Tonetti MS (2019) Aesthetic assessment after root coverage of multiple adjacent recessions with coronally advanced flap with adjunctive collagen matrix or connective tissue graft: randomized clinical trial. J Clin Periodontol 46(5):564–571. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpe.13103

Pini Prato GP, Magnani C, Chambrone L (2018) Long-term evaluation (20 years) of the outcomes of coronally advanced flap in the treatment of single recession-type defects. J Periodontol 89(3):265–274. https://doi.org/10.1002/JPER.17-0379

Pini-Prato G, Franceschi D, Rotundo R, Cairo F, Cortellini P, Nieri M (2012) Long-term 8-year outcomes of coronally advanced flap for root coverage. J Periodontol 83(5):590–594. https://doi.org/10.1902/jop.2011.110410

Barootchi S, Chan HL, Namazi SS, Wang HL, Kripfgans OD (2020) Ultrasonographic characterization of lingual structures pertinent to oral, periodontal, and implant surgery. Clin Oral Implants Res 31(4):352–359. https://doi.org/10.1111/clr.13573

Moslemi N, Mousavi Jazi M, Haghighati F, Morovati SP, Jamali R (2011) Acellular dermal matrix allograft versus subepithelial connective tissue graft in treatment of gingival recessions: a 5-year randomized clinical study. J Clin Periodontol 38(12):1122–1129. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-051X.2011.01789.x

Kuis D, Sciran I, Lajnert V, Snjaric D, Prpic J, Pezelj-Ribaric S, Bosnjak A (2013) Coronally advanced flap alone or with connective tissue graft in the treatment of single gingival recession defects: a long-term randomized clinical trial. J Periodontol 84(11):1576–1585. https://doi.org/10.1902/jop.2013.120451

Zucchelli G, Mounssif I, Mazzotti C, Stefanini M, Marzadori M, Petracci E, Montebugnoli L (2014) Coronally advanced flap with and without connective tissue graft for the treatment of multiple gingival recessions: a comparative short- and long-term controlled randomized clinical trial. J Clin Periodontol 41(4):396–403. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpe.12224

Zucchelli G, Tavelli L, Ravida A, Stefanini M, Suarez-Lopez Del Amo F, Wang HL (2018) Influence of tooth location on coronally advanced flap procedures for root coverage. J Periodontol 89(12):1428–1441. https://doi.org/10.1002/JPER.18-0201

Funding

The work was supported by the Department of Periodontology, School of Dentistry, Universidad Científica del Sur, Lima, Peru.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Ethics on Research Committee of the Faculty of Dentistry at the Científica del Sur University and was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki declaration of 1975 as revised in the year 2000.

Informed consents

The subjects participating in the study were volunteers and provided signed informed consent.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gil, S., de la Rosa, M., Mancini, E. et al. Coronally advanced flap achieved higher esthetic outcomes without a connective tissue graft for the treatment of single gingival recessions: a 4-year randomized clinical trial. Clin Oral Invest 25, 2727–2735 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00784-020-03587-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00784-020-03587-9