Abstract

The aim of this study is to assess mortality risk and the excess of risk in patients with diabetes. Patients were 15–34 years old at diagnosis of diabetes mellitus (n = 879) in 1992 and 1993 in this national cohort from Sweden. Healthy controls were matched for gender and birth on the same day as the index cases (n = 837). The civic registration number was used to link patients and controls to the Swedish Cause of Death Registry. During follow-up, 3.3% (29/879) of patients and 1.1% (9/837; P = 0.002) of controls died. The risk for a patient with diabetes to die was almost threefold increased compared with healthy controls; hazard ratio, 2.9 (95% CI 1.4–6.2). This increased risk was significant in men; hazard ratio, 2.8 (95% CI 1.2–6.5). Diabetes as the underlying cause of death accounted for 38% (11/29) of deaths among patients. Most patients, 55% (16/29), died at home, remaining patients in hospital, 28% (8/29), or elsewhere 17% (5/29) compared to controls of whom 33% (3/9; P = 0.45) died at home, 33% (3/9; P = 1.0) in hospital, and 33% (3/9; P = 0.36) elsewhere. Only 55% (16/29) of patients had a specified day of death on death certificates compared to 100% (9/9; P = 0.016) of controls. Adult men with diabetes had an almost threefold increased risk to die within 15 years of diagnosis compared to healthy men. Most middle-aged patients with diabetes died at home and often without a specified date of death recorded.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

A century ago, type 1 diabetes was a fatal disease. The discovery of insulin in 1921 dramatically increased survival among newly diagnosed patients and is still the life-saving treatment for these patients. Since then, treatment of diabetes has been optimized in most Western countries with national programmes designed to treat diabetes. Nevertheless, several studies have indicated that patients with diabetes have an increased mortality also at a young age compared to the general population [1–5]. Total mortality for patients with type 1 diabetes varies considerably between countries [5, 6]. Some studies report on a higher relative mortality among women with diabetes [5–7], while other studies describe similar mortality in men and women [4, 8, 9]. Multiple factors have been identified to contribute to this increased mortality, such as, acute metabolic complications of diabetes, alcohol or drug misuse, mental dysfunction, suicide, and circulatory diseases [1–5].

In this study, we had a unique opportunity to analyze mortality in patients with diabetes during the first 15 years of disease in our cohort of matched patients and controls, followed for the same time period since onset of diabetes from 15 to 34 years of age [10–12].

The aim of this study is to assess mortality risk and the excess of risk in patients with diabetes.

Subjects and methods

Subjects

Since 1983, all departments of medicine and endocrinology and all primary health care units in Sweden prospectively report all incident cases of diabetes in the age group 15–34 years to the Diabetes Incidence Study in Sweden (DISS) on a standardized form. The form contains information on civic registration number, name, gender, postal address, date and place of diagnosis, presence of coma, blood glucose (fasting or random), degree of ketonuria, presence of ketoacidosis (bicarbonate <15 mmol/L and or pH < 7.3) at the time of diagnosis, treatment (insulin, OHA, diet), body weight, and height together with duration of symptoms. The reporting physician also determines the type of diabetes according to criteria defined by WHO [13] based on clinical parameters. The average number of cases per year is about 400 and 75% are classified as having type 1 diabetes, 15% as having type 2, and 10% are not possible to classify at onset. The ascertainment level of DISS has for type 1 diabetes been estimated at 86% [14]. This study is based on the 1992–1993 year cohort, when 879 patients (539 men and 340 women) were reported to DISS and/or sent in a blood sample to the central laboratory in Lund, Sweden (Table 1). During these years, a case-referent study was performed. For each case, two healthy control subjects were selected matched on day of birth and gender and alive on the day the incident case was diagnosed with diabetes. These selected controls were asked for informed consent to the study and to donate a blood sample. A total of 837 healthy control subjects (466 men and 371 women) sent in an informed consent together with a blood sample.

Methods

The 1992–1993 DISS cohort and their matched controls were linked to the Swedish Cause of Death Registry maintained by the National Board of Health and Welfare, Stockholm, Sweden, using the civic registration number. The vital status of both patients (n = 879) and controls (n = 837) was ascertained through March 2, 2009, representing a median follow-up time of 15.9 years (range, 1–17) and a total of 27,173 person-years.

The Swedish Cause of Death Registry provides information on date and cause of death (underlying and contributory causes of deaths) in terms of International Classification of Disease codes (ICD9) and ICD10). We also received paper copies of all death certificates, which allowed us to verify ICD codes and day of death, and also provided us with information on the place of death. Day of death was noted on the death certificate as defined or likely. If the date of death was noted as defined then the record from The Swedish Cause of Death Registry contained a complete date. If the date was uncertain (3–8 days were noted on the death certificate) then the date was noted as year and month (n = 7) or as year only (n = 1). In five cases, the date of death was complete in the records, but was noted as likely on the death certificate (one case) or day when subject was found dead was noted as year and month together with an interval of two to three consecutive dates (n = 4), and these cases were referred to the group as missing a specific date of death.

For the five most recent deaths (four patients and one control), no ICD codes were noted in the Swedish Cause of Death Registry. In these cases, the underlying cause of death from the death certificates was used (in patients, cardiovascular disease (two cases), suicide, and violent death but not suicide; and in the control, infection).

Current addresses were obtained from the Swedish Population and Address Register (SPAR) using the civic registration number. Existing records showed that 95% (835/879) of the patients were still alive and lived in Sweden. Likewise, 98% (818/837) of the controls were alive and lived in Sweden (March 8, 2007).

Post-mortem examinations

A coronial post-mortem examination was performed in 17 patients, of whom 12 died at home; a clinical post-mortem examination was performed in three patients who died at home and one patient who died at home was examined after death. A clinical post-mortem examination was performed in two patients who died in hospital, a clinical examination was performed before death in five patients who died in hospital, and one patient was examined after death in hospital. A coronial post-mortem examination was performed in six controls of whom three died at home and three elsewhere; a clinical examination before death was performed in two controls who died in hospital, and no information about post-mortem examination was available for one control.

Statistical analysis

Cox proportional hazard regression model was used for the estimation of hazard ratios with 95% CI. Life tables were used to illustrate survival curves. Fisher’s exact test was used to test for differences in frequencies. The statistical calculations were performed in SPSS 14.0, SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL.

Ethical considerations

This study was approved by The Regional Ethical Review Board in Lund, Sweden (414/2006 and 388/2007) and was performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration in 1964.

Results

All-cause mortality

Most patients, 69% (20/29), had type 1 diabetes; 14% (4/29) had type 2 diabetes; 10% (3/29) had unclassifiable diabetes; and finally 7% (2/29) had secondary diabetes.

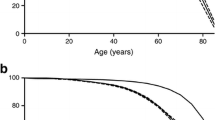

During 15 years of follow-up, 3.3% (29/879; 24 men and 5 women) of patients had died and 1.7% (15/879) had emigrated. The median age of the deceased patients was 37 years (range. 18–48). A total of 1.1% (9/837; 7 men and 2 women) of controls had died and 1.2% (10/837) had emigrated. The median age of the deceased controls was 38 years (range, 20–49). The risk for a patient with diabetes to die within the first 15 years of diagnosis was almost threefold increased compared to healthy controls in the same age group during the same observation period; hazard ratio, 2.9 (95%CI 1.4–6.2; Fig. 1). This increased risk of an early death was significant in men; hazard ratio 2.8 (95%CI 1.2–6.5). A similar pattern was found among women, hazard ratio 3.5 (95%CI 0.70–17.4).

Cause-specific mortality

Diabetes was identified as the most common cause of death (underlying cause of death) accounting for 38% (11/29) of deaths of the patients (Table 2). Ketoacidosis or coma was listed for five of these patients. Nine, eight being men, of the patients were recorded to have died from diabetes at home without a specified date of death on their death certificates. An additional three patients also died at home without a specified date of death (Table 3). Diabetes was listed as a contributory cause of death in an additional 14% (4/29) of the patients. The second most common cause of death in patients was cardiovascular disease listed in 21% (6/29) of patients (acute myocardial infarction (two cases), atherosclerotic heart disease, heart failure (two cases), or pulmonary embolism). Cardiovascular disease was identified as a contributory cause of death in another patient (atherosclerotic heart disease). The underlying cause of death or contributory cause of death was not related to diabetes in 14 patients of which five were cardiovascular disease, three were intoxications with medicines, drugs or alcohol where the purpose of the intake was unclear, three were cancers, two were suicides, and one was violent cause but not suicide.

Three controls died from violent causes, of which two were obvious suicide and one died from a car accident. Two controls died from intoxications with medicines, drugs or alcohol where the purpose of the intake was unclear. The remaining four controls died from cancer, myocardial infarction, graft versus host disease, and from infection. The control dying from infection also had diabetes as a contributory cause of death.

Place of death

Most patients died at home, 55% (16/29); almost a third of the patients, 28% (8/29), died in hospital (Table 3); the remaining, 17% (5/29), died elsewhere (ambulance transport to hospital, in one case the address was specified but it was unclear whether it was the home of the patient or not or sites of death were not specified on the death certificate in three cases). Controls died at home, 33% (3/9; P = 0.45); in hospital, 33% (3/9; P = 1.0); or elsewhere, 33% (3/9; P = 0.36), which was similar to frequencies in patients.

Date of death

All controls (9/9) had a specified day of death both in the records from the Swedish Cause of Death Registry and on death certificates, whereas a total of 13 out of 29 patients (45%; P = 0.016) did not have a specified day of death on their death certificates; in one case, only the year was defined. Out of these 13 patients, eight did not have a specified day of death, neither in the records from the Swedish Cause of Death Registry nor on the death certificate. In four patients with a specified date in the records, the day when they were found dead was specified to a time interval from 48 to 72 h on the death certificate. In another patient, the day of death was noted as likely on the death certificate. Twelve of these patients with no specified day of death died at home and one patient died elsewhere. Only four patients (4/16; 25%) that died at home had a specified day of death. All patients that died in hospitals had a specified day of death (n = 8).

Discussion

Our study presents an almost threefold increased mortality among middle-aged men with diabetes. Patients with diabetes often died at home without a confirmed day of death. We had expected more deaths among men since more men than women were diagnosed with diabetes at baseline (M/F = 1.59), but this does not explain the threefold increased risk among men with diabetes compared with healthy men.

Diabetes was the most frequent cause of death, listed as the underlying cause of death or contributory cause of death, in 52% of the patients. We had expected that more patients compared to controls would die in hospitals due to their diabetes and complications to diabetes. However, this was not confirmed since similar proportions of patients and controls died in hospitals. Unexpectedly, as many as 55% of patients died at home, which was similar to the proportion found among controls. Diabetes was the underlying cause of death in nine patients of whom eight were men, who died at home without a specified day of death recorded on the death certificate.

One strength of the study is that the Swedish Cause of Death Registry has a high validity. Another strength is that we had matched patients and controls in this national study. Furthermore, the vital status of both patients and controls represented a median follow-up time of 15.9 years and a total of 27,173 person-years in this study. One limitation to our study is that we do not have information about these patients’ lives or social networks close to their deaths, other than the limited information on the death certificates.

These findings confirm a previously reported increased mortality among patients with diabetes [3, 5, 15, 16]. The findings presented in this study of the home as the most common place of death for patients with diabetes is in accordance with a previous study reporting on places of deaths for young Norwegian patients with diabetes, where 39% died at home, 34% in hospitals, and 27% elsewhere [4]. In addition to this, our study also presents data on missing dates of death particularly on patients who died at home.

The finding of diabetes as the most common cause of death listed as the underlying or contributory cause of death is in accordance with previous studies reporting on mortality in young and middle-aged patients with diabetes [1–3, 5, 17]. A number of risk factors such as dyslipidemia, glycemic dysregulation, macroalbuminurea, and hypertension have been identified as contributors to the shorter life expectancy in diabetic patients and to cardiovascular complications [7, 16, 18–25]. Indeed, the second most common underlying cause of death in the present study was cardiovascular disease accounting for 21% (6/29) of the deaths in diabetic patients. One or several genetic factors, for example variants in the insulin receptor substrate-1 may contribute to the acceleration of diabetes complications in patients with diabetes [26–29].

It seems obvious that no one had contact with these patients within 48 h (in three cases) or more (in eight cases) or even up to a year (one case where only year was recorded) since the day of death could not be specified to a specific date, and in one case the date was noted as likely. The lack of a specified date of death in 45% of the patients could indicate that patients with diabetes do not have the same social network as healthy controls. A poor social support has been implicated in poor diabetes control [30]. Furthermore, boys with diabetes have been shown to have low levels of friend support [31]. A previous study based on these patients presented data on fewer conflicts with parents and less broken contacts with friends during the year prior to onset of diabetes. However, patients who later on developed autoimmune diabetes reported less success and fewer had fallen in love compared to controls [32]. Some deaths that occurred when patients were alone at home, might be explained by the dead in bed syndrome, where a sudden and unexpected death occurs most likely due to cardiac arrhythmias [33, 34]. To our knowledge, this is the first report of missing dates of death on death certificates in patients with diabetes.

In conclusion, adult men with diabetes had an almost threefold increased risk to die within 15 years after diagnosis compared with healthy men. Most middle-aged patients with diabetes died at home and most of these patients did not have a specified day of death recorded. The care of young and middle-aged people with diabetes should consider the life situation.

References

Wibell L, Nystrom L, Ostman J, Arnqvist H, Blohme G, Lithner F, Littorin B, Sundkvist G (2001) Increased mortality in diabetes during the first 10 years of the disease. A population-based study (DISS) in Swedish adults 15–34 years old at diagnosis. J Intern Med 249:263–270

Dahlquist G, Kallen B (2005) Mortality in childhood-onset type 1 diabetes: a population-based study. Diabetes Care 28:2384–2387

Waernbaum I, Blohme G, Ostman J, Sundkvist G, Eriksson JW, Arnqvist HJ, Bolinder J, Nystrom L (2006) Excess mortality in incident cases of diabetes mellitus aged 15-34 years at diagnosis: a population-based study (DISS) in Sweden. Diabetologia 49:653–659

Skrivarhaug T, Bangstad HJ, Stene LC, Sandvik L, Hanssen KF, Joner G (2006) Long-term mortality in a nationwide cohort of childhood-onset type 1 diabetic patients in Norway. Diabetologia 49:298–305

Patterson CC, Dahlquist G, Harjutsalo V, Joner G, Feltbower RG, Svensson J, Schober E, Gyurus E, Castell C, Urbonaite B, Rosenbauer J, Iotova V, Thorsson AV, Soltesz G (2007) Early mortality in EURODIAB population-based cohorts of type 1 diabetes diagnosed in childhood since 1989. Diabetologia 50:2439–2442

Asao K, Sarti C, Forsen T, Hyttinen V, Nishimura R, Matsushima M, Reunanen A, Tuomilehto J, Tajima N (2003) Long-term mortality in nationwide cohorts of childhood-onset type 1 diabetes in Japan and Finland. Diabetes Care 26:2037–2042

Laing SP, Swerdlow AJ, Slater SD, Burden AC, Morris A, Waugh NR, Gatling W, Bingley PJ, Patterson CC (2003) Mortality from heart disease in a cohort of 23, 000 patients with insulin-treated diabetes. Diabetologia 46:760–765

Green A, Borch-Johnsen K, Andersen PK, Hougaard P, Keiding N, Kreiner S, Deckert T (1985) Relative mortality of type 1 (insulin-dependent) diabetes in Denmark: 1933–1981. Diabetologia 28:339–342

Sartor G, Nystrom L, Dahlquist G (1991) The Swedish Childhood Diabetes Study: a seven-fold decrease in short-term mortality? Diabet Med 8:18–21

Torn C, Landin-Olsson M, Lernmark A, Palmer JP, Arnqvist HJ, Blohme G, Lithner F, Littorin B, Nystrom L, Schersten B, Sundkvist G, Wibell L, Ostman J (2000) Prognostic factors for the course of beta cell function in autoimmune diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 85:4619–4623

Torn C, Landin-Olsson M, Ostman J, Schersten B, Arnqvist H, Blohme G, Bjork E, Bolinder J, Eriksson J, Littorin B, Nystrom L, Sundkvist G, Lernmark A (2000) Glutamic acid decarboxylase antibodies (GADA) is the most important factor for prediction of insulin therapy within 3 years in young adult diabetic patients not classified as Type 1 diabetes on clinical grounds. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 16:442–447

Torn C, Landin-Olsson M, Lernmark A, Schersten B, Ostman J, Arnqvist HJ, Bjork E, Blohme G, Bolinder J, Eriksson J, Littorin B, Nystrom L, Sundkvist G (2001) Combinations of beta cell specific autoantibodies at diagnosis of diabetes in young adults reflects different courses of beta cell damage. Autoimmunity 33:115–120

Diabetes Mellitus (1985) Report of a WHO study group. Technical report series No 727, Geneva.

Littorin B, Sundkvist G, Schersten B, Nystrom L, Arnqvist HJ, Blohme G, Lithner F, Wibell L, Ostman J (1996) Patient administrative system as a tool to validate the ascertainment in the diabetes incidence study in Sweden (DISS). Diabetes Res Clin Pract 33:129–133

Soedamah-Muthu SS, Fuller JH, Mulnier HE, Raleigh VS, Lawrenson RA, Colhoun HM (2006) All-cause mortality rates in patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus compared with a non-diabetic population from the UK general practice research database, 1992–1999. Diabetologia 49:660–666

Soedamah-Muthu SS, Chaturvedi N, Witte DR, Stevens LK, Porta M, Fuller JH (2008) Relationship between risk factors and mortality in type 1 diabetic patients in Europe: the EURODIAB Prospective Complications Study (PCS). Diabetes Care 31:1360–1366

Tu E, Twigg SM, Duflou J, Semsarian C (2008) Causes of death in young Australians with type 1 diabetes: a review of coronial post-mortem examinations. Med J Aust 188:699–702

Ostgren CJ, Lindblad U, Melander A, Rastam L (2002) Survival in patients with type 2 diabetes in a Swedish community: Skaraborg hypertension and diabetes project. Diabetes Care 25:1297–1302

Grauslund J, Jorgensen TM, Nybo M, Green A, Rasmussen LM, Sjolie AK (2009) Risk factors for mortality and ischemic heart disease in patients with long-term type 1 diabetes. J Diabetes Complicat 24:223–228

Krishnan S, Short KR (2009) Prevalence and significance of cardiometabolic risk factors in children with type 1 diabetes. J Cardiometab Syndr 4:50–56

Futh R, Dinh W, Bansemir L, Ziegler G, Bufe A, Wolfertz J, Scheffold T, Lankisch M (2009) Newly detected glucose disturbance is associated with a high prevalence of diastolic dysfunction: double risk for the development of heart failure? Acta Diabetol 46:335–338

Pantalone KM, Kattan MW, Yu C, Wells BJ, Arrigain S, Jain A, Atreja A, Zimmerman RS (2009) The risk of developing coronary artery disease or congestive heart failure, and overall mortality, in type 2 diabetic patients receiving rosiglitazone, pioglitazone, metformin, or sulfonylureas: a retrospective analysis. Acta Diabetol 46:145–154

Wit MA, de Mulder M, Jansen EK, Umans VA (2010) Diabetes mellitus and its impact on long-term outcomes after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Acta Diabetol [Epub ahead of print] PubMed PMID: 20857149

May O, Arildsen H (2011) Long-term predictive power of heart rate variability on all-cause mortality in the diabetic population. Acta Diabetol 48:55–59

Nicolucci A (2010) Epidemiological aspects of neoplasms in diabetes. Acta Diabetol 47:87–95

Marini MA, Frontoni S, Mineo D, Bracaglia D, Cardellini M, De Nicolais P, Baroni A, D’Alfonso R, Perna M, Lauro D, Federici M, Gambardella S, Lauro R, Sesti G (2003) The Arg972 variant in insulin receptor substrate-1 is associated with an atherogenic profile in offspring of type 2 diabetic patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 88:3368–3371

Federici M, Petrone A, Porzio O, Bizzarri C, Lauro D, D’Alfonso R, Patera I, Cappa M, Nistico L, Baroni M, Sesti G, di Mario U, Lauro R, Buzzetti R (2003) The Gly972– > Arg IRS-1 variant is associated with type 1 diabetes in continental Italy. Diabetes 52:887–890

Perticone F, Sciacqua A, Scozzafava A, Ventura G, Laratta E, Pujia A, Federici M, Lauro R, Sesti G (2004) Impaired endothelial function in never-treated hypertensive subjects carrying the Arg972 polymorphism in the insulin receptor substrate-1 gene. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 89:3606–3609

Sesti G, Marini MA, Cardellini M, Sciacqua A, Frontoni S, Andreozzi F, Irace C, Lauro D, Gnasso A, Federici M, Perticone F, Lauro R (2004) The Arg972 variant in insulin receptor substrate-1 is associated with an increased risk of secondary failure to sulfonylurea in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 27:1394–1398

Chida Y, Hamer M (2008) An association of adverse psychosocial factors with diabetes mellitus: a meta-analytic review of longitudinal cohort studies. Diabetologia 51:2168–2178

Helgeson VS, Reynolds KA, Escobar O, Siminerio L, Becker D (2007) The role of friendship in the lives of male and female adolescents: does diabetes make a difference? J Adolesc Health 40:36–43

Littorin B, Sundkvist G, Nystrom L, Carlson A, Landin-Olsson M, Ostman J, Arnqvist HJ, Bjork E, Blohme G, Bolinder J, Eriksson JW, Schersten B, Wibell L (2001) Family characteristics and life events before the onset of autoimmune type 1 diabetes in young adults: a nationwide study. Diabetes Care 24:1033–1037

Tattersall RB, Gill GV (1991) Unexplained deaths of type 1 diabetic patients. Diabet Med 8:49–58

Sartor G, Dahlquist G (1995) Short-term mortality in childhood onset insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus: a high frequency of unexpected deaths in bed. Diabet Med 12:607–611

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by The Crafoord Foundation, Lund, Sweden by a research grant (20080671) to CT. The present members of the DISS-study group are Hans Arnquist, Linköping, Jan Bolinder, Stockholm, Mona Landin-Olsson, Lund, Olov Rolandsson, Umeå, Soffia Gudbjörnsdottir (President), Gothenburg and Lennarth Nyström, Umeå. The baseline study from onset of diabetes and the first 6 years of disease with yearly blood sampling as well as the matched control study was funded by National Institutes of Health, NIH grant DK 42,654 to Åke Lernmark, Malmö, Sweden. Abstracts of less than 300 words were submitted to the 45th Annual Meeting of the Scandinavian Society for the Study of Diabetes (SSSD) 6–8 May 2010 and to the 46th EASD Annual Meeting 20–24 September 2010.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors of this manuscript declare no conflicts of interests.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Törn, C., Ingemansson, S., Lindblad, U. et al. Excess mortality in middle-aged men with diabetes aged 15–34 years at diagnosis. Acta Diabetol 48, 197–202 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00592-011-0272-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00592-011-0272-2