Abstract

Background/Purpose

The Frey procedure, the coring out of the pancreatic head and longitudinal pancreaticojejunostomy, is a safe, easy, and reliable method to solve most of the problems associated with chronic pancreatitis. During long-term follow up, unexpected relapse in the pancreatic tail was encountered. The pattern of failure and the rationale for a new procedure to treat or prevent such relapse were investigated.

Methods

From 1992 to 2008, 71 patients with chronic pancreatitis underwent the Frey procedure at Tohoku University Hospital. The etiology was alcoholic in 92.6% of them, followed in incidence by idiopathic and hereditary chronic pancreatitis. In the primary operation, besides the Frey procedure, combined resection of the pancreatic tail was performed in three patients, and choledochoduodenostomy was performed in one patient. The follow-up rate was 92.9%, with a median period of 46 months.

Results

The incidence of early postoperative complications was 18.4%, with one reoperation for gastrointestinal bleeding from the splenic artery. Pain control was achieved in all patients and there was no operative mortality. During the long-term follow up of 62 patients with the Frey procedure, eight patients had relapse of inflammation and required reoperation. Five of these eight patients had a pseudocyst in the pancreatic tail and underwent distal pancreatectomy (DP).

Conclusions

Relapse occurred in alcoholic middle-aged male patients, and in the patients with hereditary and idiopathic pancreatitis. Frey-DP and Frey-spleen-preserving DP (SPDP) procedures can be performed safely and effectively to treat the relapse and to prevent relapse in the pancreatic tail.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The Frey procedure was introduced by Frey and Smith in 1987 [1] to rationally combine coring out of the pancreatic head and longitudinal pancreaticojejunostomy to provide a safe and effective solution for pain in chronic pancreatitis. By the employment of coring out, the complex branch ducts in the pancreatic head, the presence of which was thought to be the main cause of failure after the Partington and Rochelle procedure [2], is decompressed toward the pancreaticojejunal anastomosis. In 1980, in a publication in German, Beger et al. [3] introduced the Beger procedure, i.e., duodenum-preserving pancreatic head resection (DPPHR) as an organ-sparing procedure, compared to pancreaticoduodenectomy, to remove the pancreatic head, the controller of inflammation. In 1985, the Beger procedure was described in an English-language publication [4]. The Frey procedure and the Beger procedure proved to be equally effective in pain control and long-term functional outcome in a comparison study carried out by Izbicki et al. [5].

Since Seiki Matsuno first introduced the Frey procedure in Japan in 1992, this procedure has been indicated for most patients with chronic pancreatitis at our department. We have modified the resection volume of the pancreatic head so that it is less than the volume in the original procedure, and we have observed the efficacy of the procedure in terms of pain control and functional preservation afterward, even when the resection volume was further decreased to a wedge-shaped resection of the anterior parenchyma of the main pancreatic duct [6]. The indication for the Frey procedure is for patients with intractable symptoms that are not relieved by medical or endoscopic treatments, with main pancreatic duct dilatation of 5 mm or greater. During a long-term follow up, we encountered unexpected relapses of inflammation in the pancreatic tail in certain categories of patients [7]. This led us to combine distal pancreatectomy (DP) or spleen-preserving distal pancreatectomy (SPDP) with the Frey procedure to treat the relapse or to prevent the relapse in the pancreatic tail. Here we review the clinical outcome after the Frey procedure in a single institution and discuss the rationale of the new modifications.

Patients and methods

From April 1992 to December 2008, 71 patients underwent the Frey procedure for chronic pancreatitis at Tohoku University Hospital (patient demographics are shown in Table 1). The great majority of the patients were male (92.9%). The most frequent etiology was alcoholic, in 61 patients (85.9%), followed by idiopathic in 6 (8.5%) and hereditary pancreatitis in 4 (5.6%). After the operation, we followed the patients on an outpatient basis and/or by annual questionnaire correspondence.

Frey procedure

We performed the Frey procedure as follows, with a modification from the original procedure [1, 6]: after dissecting the gastrocolic ligament, we expose the anterior surface of the pancreas from the pancreatic head to the tail. We open pseudocysts as much as possible unless there is a possibility of neoplasm. The dilated main pancreatic duct is punctured using intraoperative ultrasonography and incised from the anterior surface (Fig. 1a). We extend the opening of the main pancreatic duct as much as possible to the pancreatic tail, then to the head (Fig. 1b). We ligate and dissect the anterior loop of the gastroduodenal artery at its point of crossing the main pancreatic duct. After placing hemostatic sutures to surround the coring-out region, we resect the anterior parenchyma of the Wirsung duct in a wedge shape. By limiting the resection area to the wedge-shaped anterior portion of the pancreatic head, we can avoid injuries to the common bile duct and portal vein (Fig. 2). We pick up pancreatic stones in the main duct and branches as much as possible, but it is not usually possible to remove diffuse calcification completely. We confirm the consistency of the duodenal papilla by inserting a probe from the opening of the main duct to the duodenal lumen. Frozen section of pancreatic parenchyma, including duct mucosa, is performed to rule out the possibility of a neoplasm. We dissect the jejunum at 20 cm distal to the Treitz ligament and open it longitudinally at the anti-mesenteric side, 1 cm shorter than the length of the pancreatic duct opening. We perform longitudinal side-to-side pancreaticojejunostomy using a 4/0 biodegradable monofilament running suture, and then finish the end-to-side jejunojejunal anastomosis (Fig. 1c, d). We insert a closed suction drain to the splenic hilum through the cranial space of the pancreaticojejunostomy.

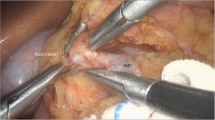

Combined resection of pancreatic tail with or without spleen preservation: Frey-DP (SPDP) procedure

In patients with relapse in the pancreatic tail after the Frey procedure and in patients with a severe inflammatory pseudocyst in the tail, we combine the Frey procedure with DP (Fig. 3a) or SPDP. In a reoperation, we divide the short portion of the jejunal limb from the anastomosis at the very end of the pancreaticojejunostomy (Fig. 3b), then transect the pancreatic tail. We re-anastomose the jejunal limb to the pancreatic stump (Fig. 3c).

When performing Frey-DP or Frey-SPDP as a primary procedure, we can transect the pancreatic tail first and open the main pancreatic duct from the stump (Fig. 4a). We can perform SPDP safely by transecting the pancreas first and dissecting branches of the splenic vessels from medial toward the splenic hilum without mobilization of the spleen. We core out the pancreatic head as described above. We open the jejunal limb to a sufficient length to cover the pancreatic stump and perform anastomosis using a 4/0 monofilament running suture (Fig. 4b, c).

Results

None of the patients had pain at the time of discharge. The median amount of bleeding was 439 mL (range 40–3100 mL, Table 2), and the median length of operation was 244 min (range 147–527 min, Table 2). Table 2 summarizes the early postoperative morbidities. The median postoperative hospital stay was 19 days (range 8–75 days). There was no operative mortality. The overall morbidity rate was 14.1% (10/71). In one patient, the splenic artery was winding within the pancreatic parenchyma and was injured during the longitudinal opening of the main pancreatic duct. We achieved complete intraoperative hemostasis with several transfixing sutures of the bleeding point, but the patient developed intraluminal bleeding on postoperative day (POD) 8. Since coiling of the distal and proximal sites of extravasation of the splenic artery could not stop the bleeding permanently, reoperation was performed, on POD 9. We ligated and divided the splenic artery at the distal and proximal sites of bleeding and achieved permanent hemostasis. The patient suffered from a postoperative pancreatic fistula but was discharged on the 54th day after the reoperation. Other early complications were treated conservatively.

During the long-term follow up (median 46 months, range 1–196 months), we encountered several unexpected relapses of inflammation that finally required reoperation (details shown in Table 3). We excluded nine patients from the cohort for the following reasons: three of them underwent Frey-DP (Frey-SPDP) at the primary operation, one underwent combined choledochoduodenostomy at the primary operation, and we were unable to follow five patients for more than 5 years, although the primary operation had been performed more than 5 years previously (follow-up rate, 92.9%). Among the 62 patients who were followed up, 8 (12.9%) reoperations were performed. Median time to the reoperation was 20 months (range 10–63 months). Most of these patients were men with alcoholism who could not stop drinking after the primary operation. Of the eight patients who required reoperation, five developed an infectious pseudocyst in the pancreatic tail and required DP in the reoperation, as shown in Fig. 3a. Another patient underwent cystojejunostomy for the relapse of a pseudocyst in the pancreatic tail 24 months after the Frey procedure. Another patient, a man in his 40 s who was an alcoholic, developed an infectious pseudocyst in the splenic hilum and received computed tomography (CT)-guided drainage, but refused reoperation and was lost follow up. One patient with idiopathic chronic pancreatitis who never drank had a similar relapse in the pancreatic tail.

One patient who had had a markedly dilated common bile duct before the first operation had several episodes of cholangitis and underwent cholecystectomy and choledochoduodenostomy 20 months after the Frey procedure. One patient presented with marked swelling of the pancreatic head with elevation of tumor markers 40 months after the Frey procedure; he underwent pancreaticoduodenectomy and finally a relapse of inflammation was revealed by histological examination.

Of the four patients with primary Frey-DP or Frey-SPDP procedures, two of the three patients with the Frey-DP procedure underwent the procedure because they had an infectious pseudocyst in the pancreatic tail at the time of the primary operation; in the third patient the procedure was performed because of a branch-type intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN) in the tail. The fourth patient, a 16-year-old female with hereditary pancreatitis, underwent the Frey-SPDP procedure because the main pancreatic duct was communicated to the pseudocyst near the splenic hilum. All four patients with the primary Frey-DP or Frey-SPDP procedures had uneventful postoperative courses.

Discussion

The principle of the Frey procedure is to decompress the branch ducts in the head of the pancreas, which is considered to be the “controller of inflammation”. The earlier Partington and Rochelle procedure cannot decompress the pancreatic head and therefore fails to solve the problem of intractable pain [1]. On the other hand, the Beger procedure is not optimal for decompressing the pancreatic body and tail if there are impacted stones in the left-side main pancreatic duct. In patients with multiple stenoses and dilatation of the main pancreatic duct, a combined longitudinal pancreaticojejunostomy is necessary [8]. The Frey procedure is safe, easy, and reliable in comparison with the highly invasive pancreaticoduodenectomy procedure. As Izbicki et al. [5] showed in a randomized prospective study, the Frey and Beger procedures are regarded as equally effective procedures, and are recommended to be performed according to the surgeon’s choice [4]. Our procedure, however, entails two important modifications of the original Frey procedure. One is a reduction of the resection volume in the pancreatic head [6] and the other is the combination of the Frey procedure with DP or SPDP to treat [7] the relapse or to prevent the relapse in the pancreatic tail.

The Frey procedure can be indicated in a great majority of patients with chronic pancreatitis, except for patients with suspicion of cancer, those with normal duct pancreatitis such as autoimmune pancreatitis, and those with pancreatitis only in the pancreatic tail. Thus, careful preoperative evaluation is necessary. Differential diagnoses of dilated duct with intraductal papillary neoplasm or pseudocyst with mucinous cystic neoplasm are crucial. These neoplastic lesions can be associated with chronic pancreatitis, too. Most of the pseudocysts associated with chronic pancreatitis can be treated by the Frey procedure without any additional technique. While cystojejunostomy can be performed for a single large pseudocyst after acute pancreatitis or pancreatic injury, for multiple pseudocysts associated with chronic pancreatitis, sufficient decompression of the entire pancreatic duct is needed. Another frequently encountered problem is stenosis of the common bile duct. Two of the 71 patients in our cohort suffered repetitive episodes of cholangitis after the Frey procedure; one of these patients required reoperation and the other required the insertion of an endoscopic stent which remained in place for several months. Most of the patients did not have cholangitis after the Frey procedure.

When we open the main pancreatic duct, we can control bleeding from the fibrotic parenchyma easily by electric cautery or with transfixing sutures. In most patients, the splenic artery runs parallel to the main pancreatic duct and is seldom injured. Careful intraoperative ultrasonography will help to avoid injury, but once injured, postoperative intraluminal bleeding can be fatal. We consider that ligation and dissection of the splenic artery at proximal and distal bleeding sites is necessary to obtain permanent hemostasis. Pessaux et al. [9] reported that the incidence of early postoperative complications after the Frey procedure was 20%, and one reoperation was required for bleeding from a gastroduodenal pseudoaneurysm following a pancreatic fistula.

In our cohort, only one patient underwent pancreaticoduodenectomy, because of suspicion of cancer with elevated serum tumor markers, 40 months after the Frey procedure. Pathological examination revealed no malignancy and suggested relapse of inflammation in the pancreatic head. This relaps may have been due to the reduced volume of resection in the pancreatic head, but this patient could not stop drinking after the primary procedure. The most frequent type of relapse was in the end of the pancreatic tail, as a pseudocyst with infection. As shown in Table 1, 95% of our patients had a pancreatic stone, but it is difficult to say how many of them had impacted or diffuse stones in the very end of the pancreatic tail. It is usually impossible to remove all stones, and postoperative CT scanning shows most stones remain in the parenchyma of the entire pancreas.

A particular patient category is the alcoholic middle-aged male and the patient with hereditary or idiopathic pancreatitis, suggesting that continuous diffuse inflammation can be a cause of relapse. Though abstinence from alcohol is strongly recommended to all patients with alcoholic pancreatitis, there are certainly some patients who cannot stop drinking. Strate et al. [10] reported that 9 (18%) out of 50 patients in a long-term follow up could not abstain from drinking. We have also encountered patients with juvenile hereditary pancreatitis and those with idiopathic pancreatitis who never drank but who required the Frey-SPDP or Frey-DP combination procedures as the eventual solution. We therefore indicate the Frey-DP or Frey-SPDP as a primary procedure for those patients who might not be able to stop drinking and for patients with hereditary or idiopathic pancreatitis. In a literature review in 1996, Kimura et al. [11] reported a case of combination of SPDP with the Puestow procedure. Holzinger et al. [12] reported a case with the Beger procedure and DP. Govil and Imrie [13] concluded that SPDP, although technically demanding, could be performed with perioperative results equivalent to those of, and they noted that SPDP led to a later onset of diabetes in chronic pancreatitis patients. The present study is the first to report the rationale for a combination of DP or SPDP with the Frey procedure to treat the relapse or to prevent relapse in the pancreatic tail.

Reoperation markedly increases the difficulty of performing DP or SPDP due to severe inflammation not only because of the reoperation but also because of the presence of an infectious pseudocyst. It is, however, sometimes safer not to mobilize the spleen, because the splenic capsule can be adherent to the diaphragm and could be easily ruptured during the mobilization. Preceding ligation and dividing of the splenic vessels before splenic mobilization helps to decrease the bleeding. Similarly, attempts to perform SPDP without mobilization could be considered even if the inflammation exists in the splenic hilum.

Since one of the concepts of the Frey procedure is organ sparing, the resection volume of DP or SPDP can be controversial. At the time of reoperation, the length of opening of the jejunal limb (Fig. 3b) should be sufficient to cover the pancreatic stump. We usually leave 3–5 cm of the jejunal limb end intact at the primary operation to avoid tension of the mesenterium (Fig. 1d). If necessary, the vascular loop in the mesenterium can be used to elongate the jejunal limb. In the primary Frey-DP or Frey-SPDP procedure, the length of resection is variable. Rupture of the main pancreatic duct made the decision easier in our patient with juvenile hereditary pancreatitis. If we transect the pancreas closer to the pancreatic head, the anastomosis becomes easier, but endocrine and exocrine function may be reduced.

In conclusion, the Frey procedure is safe, easy, and reliable for solving most of the problems associated with chronic pancreatitis. Our modifications to decrease the amount of resection in the pancreatic head and the combining of DP or SPDP with the Frey procedure can be performed safely and effectively. Primary Frey-DP or Frey-SPDP should be considered as the primary operation in patients with alcoholic, hereditary, or idiopathic chronic pancreatitis.

References

Frey CF, Smith J. Description and rationale of a new operation for chronic pancreatitis. Pancreas. 1987;2:701–7.

Partington PF, Rochelle RE. Modified Puestow procedure for retrograde drainage of the pancreatic duct. Ann Surg. 1960;152:1037–43.

Beger HG, Witte C, Kraas E, Bittner R. Erfarung mit einer das Duodenum erhaltenden Pankreaskopf-resektion bei chronischer Pancreatitis. Chirurg. 1980;51:303–9.

Beger HG, Krautzberger W, Bittner R, Büchler M, Limmer J. Duodenum-preserving resection of the head of the pancreas in patients with severe chronic pancreatitis. Surgery. 1985;97:467–73.

Izbicki JR, Bloechle C, Knoefel WT, Kuechler T, Binmoeller KF, Broelsch CE. Duodenum-preserving resection of the head of the pancreas in chronic pancreatitis. A prospective, randomized trial. Ann Surg. 1995;221:350–8.

Sakata N, Egawa S, Motoi F, Goto M, Matsuno S, Katayose Y, et al. How much of the pancreatic head should we resect in Frey’s procedure? Surg Today. 2009;39:120–7.

Egawa S, Kitamura Y, Sakata N, Ottomo S, Abe H, Akada M, et al. Reoperation for relapsing pancreatitis after Frey procedure for chronic pancreatitis. Jpn J Gastroenterol Surg. 2009;42:466–72. (in Japanese with English abstract).

Beger HG, Kunz R, Schoenberg MH. Duodenum-preserving resection of the pancreatic head—a standard procedure for chronic pancreatitis. In: Beger HG, Warshaw AL, Büchler MW, Carr-Locke DL, Neoptolemos JP, Russell C, Sarr MG, editors. The pancreas. Berlin: Blackwell Science; 1998. p. 870–6.

Pessaux P, Kianmanesh R, Regimbeau JM, Sastre B, Delcenserie R, Sielezneff I, et al. Frey procedure in the treatment of chronic pancreatitis: short-term results. Pancreas. 2006;33:354–8.

Strate T, Taherpour Z, Bloechle C, Mann O, Bruhn JP, Schneider C, et al. Long-term follow-up of a randomized trial comparing the Beger and Frey procedure for patients suffering from chronic pancreatitis. Ann Surg. 2005;241:591–8.

Kimura W, Inoue T, Futakawa N, Shinkai H, Han I, Muto T. Spleen-preserving distal pancreatectomy with conservation of the splenic artery and vein. Surgery. 1996;120:885–90.

Holzinger F, Moser JJ, Baer HU, Büchler MW. Pancreatic head enlargement associated with a pancreatitis- induced intrasplenic pseudocyst in a patient with chronic pancreatitis: organ preserving surgical treatment. Hepatogastroenterology. 1996;43:1645–9.

Govil S, Imrie CW. Value of splenic preservation during distal pancreatectomy for chronic pancreatitis. Br J Surg. 1999;86:895–8.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

About this article

Cite this article

Egawa, S., Motoi, F., Sakata, N. et al. Assessment of Frey procedures: Japanese experience. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 17, 745–751 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00534-009-0185-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00534-009-0185-4