Abstract

Purpose

Family caregivers (FCs) are crucial resources in caring for cancer patients at home. The aim of this investigation was (1) to measure the prevalence of unmet needs reported by FCs of cancer patients in home palliative care, and (2) to investigate whether their needs change as their socio-demographic characteristics and the patients’ functional abilities change.

Methods

FCs completed a battery of self-report questionnaires, including the Cancer Caregiving Tasks, Consequences, and Needs (CaTCoN).

Results

Data were collected from 251 FCs (74 men and 177 women, mean age 58.5 ± 14.2 years). Most of the participants experienced a substantial caregiving workload related to practical help (89.8%), provided some or a lot of personal care (73.1%), and psychological support (67.7%) to patients. More than half of the FCs reported that the patient’s disease caused them negative physical effects (62.7%). Emotional, psychosocial, and psychological needs were referred. Some FCs reported that the patient’s disease caused them a lot of stress (57.3%) and that they did not have enough time for friends/acquaintances (69.5%) and family (55.7%). The need to see a psychologist also emerged (44.0%). Age, caregiving duration, and patients’ functional status correlated with FCs’ unmet needs. Women reported more negative social, physical, and psychological consequences and a more frequent need to talk to a psychologist.

Conclusion

The analysis demonstrated that cancer caregiving is burdensome. The results can guide the development and implementation of tailored programs or support policies so that FCs can provide appropriate care to patients while preserving their own well-being.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Family caregivers (FCs) have become crucial resources in caring for cancer patients at home. They are the patients’ primary support and typically, they provide the vast majority of assistance, assuming caring duties and responsibilities [1,2,3]. In fact, FCs play a pivotal role in direct and indirect care tasks, such as assisting with activities of daily living, optimizing therapies through treatment compliance, managing symptoms and patients’ physical impairments, providing emotional support, and preventing isolation.

At present, FCs can be considered essential health team members, as they are responsible for care activities once provided only by professionals. However, often, they do not feel adequately trained or prepared for these tasks and may experience a number of mixed emotions including irritability, helplessness, anxiety, anger, and sadness. Furthermore, there is global recognition that caregiving is burdensome and that it could be associated with physical symptoms (e.g., poor sleep quality, fatigue, loss of appetite, and weight loss), decreased mental well-being (e.g., distress, anxiety, and depression), and social and financial problems (e.g., isolation and reduced work hours) [1,2,3,4].

In this context, it has been recommended to examine the impact of cancer not only on cancer patients but also on their FCs. Indeed, they should be considered as co-patients since, according to the World Health Organization, the patient and his/her FC should be viewed as the “unit of care” [5]. There is growing interest in assessing the prevalence of FCs’ needs (e.g. comprehensive cancer care, information, emotional and psychological needs) [6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23], but few studies have focused on the psycho-physical well-being of FCs assisting cancer patients in a home palliative care setting [6, 11, 13, 19, 23]. The evaluation of their needs has often been informal and undocumented, making caregivers’ needs less “detectable” [6,7,8].

To identify FCs’ current needs, the concept of “unmet needs” was adopted in this investigation. Unmet needs are defined as the “requirement for some desirable, necessary, or useful action to be taken or some resource to be provided, in order for the person to attain optimal well-being” [9]. Therefore, this concept provides information about lack of support and can be employed to carry on supporting actions in the most critical dimensions.

The literature associated with this concept indicates that unmet needs are multidimensional and that they compromise FCs’ quality of life and adversely impact on their distress with negative consequences on the quality of care they provide to the patients [6,7,8, 10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21]. With respect to prevalence, practical unmet needs were discussed in almost all the studies [10,11,12,13,14, 16, 19]. The most commonly reported were assistance with personal care [10, 11, 13, 14, 16, 19, 20], support with technical daily tasks [12,13,14, 19] and respite care [13, 19, 24]. Emotional, psychosocial, and financial needs emerged as other prevalent domains [8, 12, 14, 16, 21]. In particular, these needs concern coping with emotional distress, the ability to give emotional support to the patients, and the lack of personal time and social life [8, 12]. Several studies aimed to identify the main variables associated with FCs reporting more frequently unmet needs, focusing on socio-demographic data, caregiving intensity, and setting [8, 12, 25]. Results are conflicting and vary across studies.

Given the interest of the topic and the literature data described above, the main challenge of this investigation was the quantification of unmet needs to obtain a useful depiction of FCs’ experiences in the home palliative care setting. This investigation aimed to (1) measure and understand the prevalence of unmet needs reported by FCs of cancer patients in home palliative care and (2) investigate whether FCs’ needs change as their socio-demographic characteristics and the patients’ functional abilities change. Identifying and quantifying the prevalence of unmet needs will guide the development and implementation of tailored programs or support policies so that FCs can provide high-quality care to patients while preserving their own health and well-being.

Materials and methods

Setting

The National Tumor Assistance (ANT) Foundation is an Italian no-profit organization that has been providing free medical, nursing, psychological, and social home oncological assistance in 11 Italian regions since 1985 [26, 27]. ANT is one of Europe’s leading organizations in the field of home palliative care and pain management. The assistance is activated at the request of the patient’s primary care physician, and it is provided throughout Italy by multidisciplinary teams. The home care assistance is guaranteed, free of charge, 24/7 with paid physicians, nurses, and psychologists providing regular home visits.

Study sample

To be included in the study, participants had to be (I) FCs of cancer patients assisted by the ANT home palliative care program; (II) living with the patient; (III) aged >18 years; and (IV) with a high level of fluency in the Italian language, both comprehension and speaking.

Procedure and assessment

The participants were recruited by the ANT health care professionals. They explained the rationale and aims of the study to the eligible participant and conducted the informed consent conversation. All the FCs were asked to autonomously fill out a socio-demographic data record and a battery of self-report questionnaires, all in Italian. They underwent tests during the home-care assistance provided by ANT. The questionnaires and the demographic data record were returned to the health care professionals in the same session or at the next home visit. Data were collected from August 2017 to February 2018.

Unmet needs assessment

Participants filled out the Cancer Caregiving Tasks, Consequences, and Needs (CaTCoN), a 72-item questionnaire measuring cancer caregiving tasks, consequences, and needs [27, 28]. The CaTCoN contains nine subscales (each containing between two and 14 items) and 31 single items, including two open-ended items for qualitative comments [28]. The majority of items contain four ordinal response categories and a “don’t know/not relevant” category. These items are scored by excluding the don’t know/not relevant category and assigning the remaining four response categories the scores 0 (no problems/unmet needs), 1, 2, and 3 (maximum problems/unmet needs). A few items contain only two response categories (“no” and “yes”) which are assigned the scores 0 (no problems/unmet needs) and 1 (maximum problems/unmet needs). Subscale scores are estimated as the mean of subscale item scores. The validity and reliability of the CaTCoN were evaluated by using psychometric analyses and were found to be satisfactory, with Cronbach’s alpha (α) ranging 0.65–0.95 [29].

Patients’ functional status

Participants completed the Index of Independence in Activities of Daily Living and the Index of Independence in Instrumental Activities of Daily Living with reference to their patients’ condition.

The Index of Independence in Activities of Daily Living (ADL) [30, 31] is a scale that contains six basic activities performed by individuals on a daily basis. It includes the fundamental skills necessary for independent living at home or in the community, and it comprises the following areas: grooming/personal hygiene, dressing, toileting, transferring/ambulating, continence, and eating. FCs were asked to indicate one of the categories for each of the activities listed. Each category indicates how much assistance is needed by their loved ones in performing that activity. The total score ranges from 0 (low function, dependent) to 6 (high function, independent). Although no formal reliability and validity reports could be found in the literature, the tool is used extensively as a flag signaling functional capabilities of older adults in clinical and home environments [31].

The Index of Independence in Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL) [32, 33] is a scale that contains eight actions (shopping, managing finances, housekeeping, laundry, meal preparation, ability to use transportation and telephone, and ability to take medications) that are important to be able to live independently. FCs were asked whether they had any difficulty doing each of the instrumental daily activity: the impairment in performing a specific IADL, defined as the inability to perform the task successfully without external assistance, corresponds to score 0. The final score is the sum of the scores for each single activity. The total score ranges from 0 (low function, dependent) to 8 (high function, independent). Inter-rater reliability was established at .85. Validity was tested, and the correlations between the IADL scale and the other measures of functional status ranged between 0.40 and 0.61. The reproducibility coefficient was 0.96 for men and 0.93 for women (n = 97 and n = 168, respectively).

Demographic variables

Socio-demographic variables, including sex, age, marital status, education level, working status, and type of relationship with the patient, were collected from all FCs.

Ethical issue

The trial was carried out in full accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice. The investigation received formal approval from the Area Vasta Emilia Centro Research Ethics Committee of Emilia-Romagna Region (AVEC; approval no. 17079), where the ANT Research Unit is located. Participants provided informed written consent for participation in the investigation, data analysis, and publication. Each participant was assigned a code. Anonymized paper questionnaires were archived separately from the informed consent forms, and anonymized data were stored in an electronic database in the research department of the ANT Foundation.

Statistical analyses

For the total sample of FCs, frequency scores for the answers to each CaTCoN item were calculated. The aspects perceived as most problematic by the total sample are pointed out using a cut-off of 30% of FCs reporting problems or unmet needs, according to Lund et al. [15]. Themes of CaTCoN and items covering each theme were defined according to Lund et al. [28]. After excluding don’t know/ not relevant responses, CaTCoN subscale scores were estimated as the mean of subscale items scores when at least half of the subscale items were completed.

According to the Shapiro-Wilk test for normal distribution, the CaTCoN themes were not normally distributed. Mean, standard deviation, and missing data are shown for each theme. The strength and direction of the relationship between each CaTCoN theme and the age of the caregiver, duration of the assistance (dichotomized as less or more than 6 months), and functional status of the patient (ADL and IADL scores) were analyzed by bivariate Spearman’s rank correlations. Correlation coefficients (ρ) and p are shown for each correlation.

The comparisons of the score for each theme between men and women were performed by Mann-Whitney U test. The comparison of the percentage of FCs reporting the need to talk to a psychologist between men and women was analyzed by Pearson’s chi-square test. A two-sided p < .05 was considered significant. The statistical analyses were performed utilizing SPSS 25.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Study population

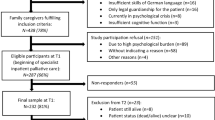

The final study population included 251 adult FCs of cancer patients assisted by the ANT home palliative care program from 21 Italian cities. Figure 1 details participant recruitment and retention.

Table 1 shows the socio-demographic characteristics of the FCs included in the investigation. The majority of the FCs were female (n =177, 70.5%), with a mean age of 58.2 years (SD = 14.2years). About half of the FCs were spouses of patients (51.4%), followed by adult children (34.3%). Most of them (81.7%) had been providing care to the patient for more than 6 months. A substantial proportion of FCs had a job (45.0%) and had a high school education (43.0%).

Prevalence of caregiving tasks and unmet needs

This article reports the results concerning the FCs’ supportive care needs. This included 8 CaTCoN subscales and 11 CaTCoN single items. FCs’ interaction with health care professionals is the subject of another study.

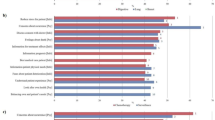

The distribution of the FCs’ answers to the most problematic items (cut off >30%) is shown in Table 2.

Large proportions of FCs experienced a substantial caregiving workload: 89.8% of them provided some or a lot of practical help to the patient (item 1a), 73.1% provided some or a lot of personal care (item 1b), and 67.7% provided some or a lot of psychological support (item 1c). Moreover, 66.7% of FCs felt to some or to a high degree responsible for keeping track of patient’s referrals and appointments for examinations and treatment (item 2), while 48.8% spent a lot of time transporting the patient (item 4).

More than half of the FCs (62.7%) reported a little or some negative effects on their own physical health (item 6b), and 57.3% reported that the patient’s disease caused them a lot of stress (item 6a). A part of them (44.0%) needed to see a psychologist (item 34). Regarding the negative social consequences caused by caregiving, 69.5% and 55.7% of the FCs reported that they did not have enough time for friends/acquaintances and the rest of the family respectively (item 6d and 6c).

A large proportion of FCs (50.6%) expressed the need to lead a “normal” life while being a caregiver to some or a high degree (item 40), and 45.7% reported the need to take a break from the practical tasks to some or a high degree (item 38). Only 23.6% and 22.2% respectively had the possibility to do this to a high or some degree (item 41 and item 39).

Regarding the positive experiences of caregiving, increased awareness of the important things in life and valuing relationships with other people more were experienced by 80.2% and 59.5% of the FCs, respectively (item 6e and item 6g).

Associations between unmet needs, FCs’ socio-demographic characteristics, and patients’ functional abilities

The themes of CaTCoN were defined as previously described. For each theme, the items considered, mean score, standard deviation, and missing data are shown in Table 3.

The analysis of the correlation between themes of CaTCoN, age of the caregiver, duration of the assistance, and functional status of the patient (ADL and IADL) are shown in Table 4.

The FCs’ age was correlated with the negative physical consequences (ρ = 0.143, p = 0.028) and the impossibility of taking a break from the caregiving tasks (ρ = 0.148, p = 0.022). The FCs’ age was inversely correlated with the positive psychological consequences (ρ = − 0.166, p = 0.010).

Duration of the caregiving was correlated with the caregiving tasks (ρ = 0.141, p = 0.028) and the negative psychological consequences (ρ = 0.132, p = 0.040).

Patients’ functional status was inversely correlated with the caregiving tasks (ADL: ρ = − 0.338, p < 0.001; IADL: ρ = − 0.311, p < 0.001), and the physical (ADL: ρ = − 0.136, p = 0.037; IADL: ρ = − 0.190, p = 0.003), and social (ADL: ρ = − 0.280, p < 0.001; IADL: ρ = − 0.323, p < 0.001) consequences.

The themes of CaTCoN according to FCs’ gender are shown in Table 5. Women reported more negative social consequences (p < 0.001) and higher levels of physical (p = 0.005) and psychological (p = 0.005) consequences. Finally, a higher percentage of women reported the need to talk to a psychologist (p = 0.023).

Discussion

Analysis of FCs’ unmet needs demonstrated that cancer caregiving is burdensome. FCs have unmet needs across different domains. A large number of participants experienced a substantial caregiving workload related to practical help, mainly support for care, and assistance (e.g., help with the patient’s daily activities, therapeutic drug monitoring, and coordination for examinations and treatment). Emotional, psychological, and psychosocial needs emerged as other prevalent domains. FCs reported the need both to cope with their emotional distress and to provide emotional and psychological support to the patients, helping them to deal with their feelings. These results are in line with the literature [8, 10,11,12,13,14, 16, 19, 20].

Moreover, results revealed a range of negative caregiving consequences, demonstrating that being a family caregiver is demanding and has its costs. Participants reported that their well-being is highly affected, especially with regard to increased levels of stress and poor physical health. Furthermore, in this investigation sample, the majority of FCs reported that caregiving tasks limit their respite care and personal time, negatively influencing their personal care (e.g. healthy diet, exercise, sleep routine) and increasing their risk of loneliness and social isolation from both family and friends. These results are in accordance with previous findings [9, 17, 24] and constitute an important outcome to highlight and to keep in consideration in safeguarding FCs. In fact, research has shown the link between the lack of social connection and adverse health consequences: high blood pressure, heart disease, obesity, a weakened immune system, anxiety, depression, cognitive decline, and even death.

Our results demonstrate that the most important caregivers’ needs were related to patient care. This is in accordance with previous studies [8, 24] and may suggest that FCs are mainly dealing with the patient’s needs rather than their own ones. However, participants recognized their own personal needs. A large number of FCs reported a moderate or high need to see a psychologist as well as to take a break or to lead a “normal” life, expressing the necessity to balance the patient’s needs with their own. The percentage of FCs who needed to see a psychologist as a consequence of the patient’s illness was higher than in other studies. In a recent Italian survey, 15% of caregivers of cancer patients felt that appointments with a psychologist were important [34]. This could be due to the fact that FCs of patients with advanced cancer need help in processing their emotions and dealing with continual uncertainty about patients’ practical needs, emotional needs, functional decline, and physical symptoms [35].

Contrary to some previous research [14, 16, 21], financial consequences did not appear to be a significant concern for the participants of this investigation. This is probably due to the Italian healthcare policy where palliative care is guaranteed and financed by the government and the tertiary sector.

Correlation analysis revealed a few variables that were associated with cancer FCs’ unmet needs, confirming that the ability to individualize a sub-group of caregivers at risk by socio-demographic variables is limited [8, 12, 25, 36]. Higher FCs’ age was related to the perception of more severe negative physical consequences and with an increased impossibility of taking a break from the caregiving tasks, contrary to a previous review [25] that highlighted that younger FCs showed more unmet needs. Regarding gender, women showed more negative consequences at all levels, both physical and psychosocial. This is in line with a study that indicated that being female was a variable associated with a higher probability to report unmet needs [12], and women reported more the need to talk to a psychologist. Longer duration of the caregiving was correlated with increased supportive care tasks and with more severe negative psychological consequences. The worsening of the patients’ functional status was associated with increased caregiving tasks and greater physical and social consequences. Similarly, the results of other studies showed that higher-intensity caregiving [36] and taking care of patients with low physical performance [25] were found to be significant predictors of FCs more frequently reporting unmet needs.

The results of the present investigation should be verified with further research in the home setting. However, the considerable number of unmet needs that emerged is in line with the study by Wang et al. [25]. They demonstrated that FCs in different caregiving settings show different levels of unmet needs: the highest level of needs was found in the home setting, an intermediate level in general hospitals, and the minor level in hospice care units.

In conclusion, a high percentage of FCs identified positive aspects of caregiving. Both quantitative and qualitative studies have documented that a stressful activity such as caring for a cancer patient can lead to personal growth through changing relationships with others and renewed perspectives on living [19, 37, 38]. FCs may use these positive interpretations as a meaning-based coping resource. Furthermore, it was demonstrated that the identification of meaning in the caregiving experience of patients with advanced oncological illness can be considered a protective factor [38]. FCs who cannot identify any positive aspects of caring may be at particular risk for depression and poor health outcomes, and they also are more likely to institutionalize their care-recipient earlier than others [39]. However, our results showed that positive consequences tend to be less experienced by the older FCs. We might presume that older FCs usually have a limited social network, and the patient they are taking care of may be one of their few contacts. It has been observed in the literature that post-traumatic growth may be associated with perceived social support [40]. We could also presume that older FCs may already be aware of what is important for them in life and thus might not feel an increased awareness of the important things in life, focusing more on negative aspects.

Strengths and limitations

To the knowledge of the authors, few studies have investigated the FCs’ unmet needs in the home palliative care, and this is the first national investigation on this setting. Major strengths of the study are the large sample size and the quantitative measurement of a wide range of aspects regarding FCs’ unmet supportive care needs. Female caregivers were overrepresented in the current investigation sample, confirming the characteristics already observed in the literature about cancer FCs in Italy, where this role is played mostly by women (70–80%) with an average age of 50–55 years [41]. The current research has limitations that apply to any survey, including the sample design. Participants are FCs supporting palliative cancer patients with heterogeneous malignancies at home, and we are therefore unable to distinguish whether the results varied by cancer type. Furthermore, the results cannot be generalized across all treatment phases and different caregiving settings, for example general hospital or hospice care unit.

Conclusions

FCs perform a crucial social and economic role in the home care setting. With cancer incidence rising, the health system will rely more and more on collaboration between healthcare professionals and FCs to provide appropriate care for the health and well-being of patients. Therefore, it is essential to have properly qualified and trained FCs, as caregivers with unmet needs cannot provide high-quality care [17]. The results of the current investigation can thus enlighten the development of interventions designed to meet caregiver needs and improve the overall quality of palliative and end-of-life care. Healthcare providers and clinicians should develop and implement tailored support policies and guidelines so that FCs can provide appropriate care to patients while preserving their own health and well-being. To achieve this, it could be useful to adopt a patient-and-family-centered perspective [5] and implement FC tailored screening instruments into daily clinical routine, in order to identify FCs at risk and better support them. The literature clearly indicates that a multidisciplinary approach to supportive care for FCs is needed. In particular, psychosocial interventions designed to improve quality of life, physical health, and well-being, paying particular attention to individual personal needs, provided advantages [42]. Interventions focusing on coping skills training [43] and stress management [44] also seem promising. Furthermore, it was found that mindfulness-based interventions could enhance psychological well-being and reduce the burden for FCs [45].

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code availability

Not applicable.

References

Grov EK, Dahl AA, Fosså SD et al (2006) Global quality of life in primary caregivers of patients with cancer in palliative phase staying at home. Support Care Cancer. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-006-0026-9

Robison J, Fortinsky R, Kleppinger A et al (2009) A broader view of family caregiving: effects of caregiving and caregiver conditions on depressive symptoms, health, work, and social isolation. J Gerontol Ser B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 64B:788–798. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbp015

Ahmed S, Naqvi SF, Sinnarajah A et al (2020) Patient and caregiver experiences with advanced cancer care: a qualitative study informing the development of an early palliative care pathway. BMJ Support Palliat Care bmjspcare-2020-002578. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjspcare-2020-002578

Zavagli V, Miglietta E, Varani S et al (2016) Associations between caregiving worries and psychophysical well-being. An investigation on home-cared cancer patients family caregivers. Support Care Cancer 24:857–863. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-015-2854-y

WHO (2020) Palliative Care - World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/palliative-care

Zavagli V, Raccichini M, Ercolani G et al (2019) Care for carers: an investigation on family caregivers’ needs, tasks, and experiences. Transl Med @ UniSa 19:54–59

Girgis A, Abernethy AP, Currow DC (2015) Caring at the end of life: do cancer caregivers differ from other caregivers? BMJ Support Palliat Care 5:513–517. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjspcare-2013-000495

Sklenarova H, Krümpelmann A, Haun MW et al (2015) When do we need to care about the caregiver? Supportive care needs, anxiety, and depression among informal caregivers of patients with cancer and cancer survivors. Cancer 121:1513–1519. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.29223

Campbell HS, Sanson-Fisher R, Taylor-Brown J et al (2009) The cancer Support Person’s Unmet Needs Survey. Cancer 115:3351–3359. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.24386

Given BA, Given CW, Sherwood PR (2012) Family and caregiver needs over the course of the cancer trajectory. J Support Oncol 10:57–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.suponc.2011.10.003

Harding R, Epiphaniou E, Hamilton D et al (2012) What are the perceived needs and challenges of informal caregivers in home cancer palliative care? Qualitative data to construct a feasible psycho-educational intervention. Support Care Cancer 20:1975–1982. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-011-1300-z

Lambert SD, Harrison JD, Smith E et al (2012) The unmet needs of partners and caregivers of adults diagnosed with cancer: a systematic review. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2:224–230. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjspcare-2012-000226

Ventura AD, Burney S, Brooker J et al (2014) Home-based palliative care: a systematic literature review of the self-reported unmet needs of patients and carers. Palliat Med 28:391–402. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216313511141

Lund L, Ross L, Petersen MA, Groenvold M (2014) Cancer caregiving tasks and consequences and their associations with caregiver status and the caregiver’s relationship to the patient: a survey. BMC Cancer 14:541. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-14-541

Lund L, Ross L, Petersen MA, Groenvold M (2015) The interaction between informal cancer caregivers and health care professionals: a survey of caregivers’ experiences of problems and unmet needs. Support Care Cancer 23:1719–1733. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-014-2529-0

Hashemi M, Irajpour A, Taleghani F (2018) Caregivers needing care: the unmet needs of the family caregivers of end-of-life cancer patients. Support Care Cancer 26:759–766. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-017-3886-2

Chen SC, Chiou SC, Yu CJ, et al. (2016) The unmet supportive care needs—what advanced lung cancer patients’ caregivers need and related factors. Support Care Cancerhttps://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-016-3096-3

Park SM, Kim YJ, Kim S et al (2010) Impact of caregivers’ unmet needs for supportive care on quality of terminal cancer care delivered and caregiver’s workforce performance. Support Care Cancer 18:699–706. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-009-0668-5

Hudson P (2004) Positive aspects and challenges associated with caring for a dying relative at home. Int J Palliat Nurs 10:58–65. https://doi.org/10.12968/ijpn.2004.10.2.12454

Sharpe L, Butow P, Smith C et al (2005) The relationship between available support, unmet needs and caregiver burden in patients with advanced cancer and their carers. Psychooncology 14:102–114. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.825

Jo S, Brazil K, Lohfeld L, Willison K (2007) Caregiving at the end of life: perspectives from spousal caregivers and care recipients. Palliat Support Care 5:11–17. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1478951507070034

Adejoh SO, Boele F, Akeju D et al (2021) The role, impact, and support of informal caregivers in the delivery of palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: a multi-country qualitative study. Palliat Med 35:552–562. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216320974925

Bijnsdorp FM, Pasman HRW, Boot CRL et al (2020) Profiles of family caregivers of patients at the end of life at home: a Q-methodological study into family caregiver’ support needs. BMC Palliat Care 19:51. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-020-00560-x

Friðriksdóttir N, Sævarsdóttir Þ, Halfdánardóttir SÍ et al (2011) Family members of cancer patients: needs, quality of life and symptoms of anxiety and depression. Acta Oncol (Madr) 50:252–258. https://doi.org/10.3109/0284186X.2010.529821

Wang T, Molassiotis A, Chung BPM, Tan J-Y (2018) Unmet care needs of advanced cancer patients and their informal caregivers: a systematic review. BMC Palliat Care 17:96. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-018-0346-9

Casadio M, Biasco G, Abernethy A et al (2010) The National Tumor Association Foundation (ANT): a 30 year old model of home palliative care. BMC Palliat Care 9:12. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-684X-9-12

Zavagli V, Raccichini M, Ostan R et al (2021) The ANT Home Care Model in Palliative and End-of-Life Care. An Investigation on Family Caregivers’ Satisfaction with the Services Provided. Transl Med UniSa 23:22. https://doi.org/10.37825/2239-9747.1022

Lund L, Ross L, Petersen MA et al (2020) Improving information to caregivers of cancer patients: the Herlev Hospital Empowerment of Relatives through More and Earlier information Supply (HERMES) randomized controlled trial. Support Care Cancer 28:939–950. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-019-04900-3

Lund L, Ross L, Petersen MA, Groenvold M (2014) The validity and reliability of the ‘Cancer Caregiving Tasks, Consequences and Needs Questionnaire’ (CaTCoN). Acta Oncol (Madr) 53:966–974. https://doi.org/10.3109/0284186X.2014.888496

Katz S, Downs TD, Cash HR, Grotz RC (1970) Progress in development of the index of ADL. Gerontologist 10:20–30. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/10.1_Part_1.20

Wallace M, Shelkey M (2001) Katz Index of Independence in Activities of Daily Living. Home Healthc Nurse 19:323–324. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004045-200105000-00020

Lawton MP, Brody EM (1969) Assessment of older people: Self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologisthttps://doi.org/10.1093/geront/9.3_Part_1.179

Graf C (2008) The Lawton Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Scale. AJN, Am J Nurs 108:52–62. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NAJ.0000314810.46029.74

Berardi R, Ballatore Z, Bacelli W et al (2015) Patient and caregiver needs in oncology. An Italian Survey. Tumori J 101:621–625. https://doi.org/10.5301/tj.5000362

Mosher CE, Adams RN, Helft PR et al (2016) Family caregiving challenges in advanced colorectal cancer: patient and caregiver perspectives. Support Care Cancer 24:2017–2024. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-015-2995-z

Beach SR, Schulz R (2017) Family caregiver factors associated with unmet needs for care of older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 65:560–566. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.14547

Wong WKT, Ussher J, Perz J (2009) Strength through adversity: bereaved cancer carers’ accounts of rewards and personal growth from caring. Palliat Support Care 7:187–196. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1478951509000248

Palacio C, Limonero JT (2020) The relationship between the positive aspects of caring and the personal growth of caregivers of patients with advanced oncological illness. Support Care Cancer 28:3007–3013. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-019-05139-8

Cohen CA, Colantonio A, Vernich L (2002) Positive aspects of caregiving: rounding out the caregiver experience. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 17:184–188. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.561

Nouzari R, Najafi SS, Momennasab M (2019) Post-traumatic growth among family caregivers of cancer patients and its association with social support and hope. Int J Commun Based Nurs Midwifery 7:319–328. https://doi.org/10.30476/IJCBNM.2019.73959.0

ISTAT (2011) Caregiver: quanti sono, i dati ISTAT Caregivers: how many are there, ISTAT data. In: PMI. www.pmi.it/impresa/normativa/approfondimenti/149510/caregiver-quanti-i-dati-istat.html

Treanor CJ, Santin O, Prue G, et al. (2019) Psychosocial interventions for informal caregivers of people living with cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Revhttps://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD009912.pub2

Candy B, Jones L, Drake R, et al. (2011) Interventions for supporting informal caregivers of patients in the terminal phase of a disease. Cochrane Database Syst Revhttps://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD007617.pub2

Hudson P (2003) A conceptual model and key variables for guiding supportive interventions for family caregivers of people receiving palliative care. Palliat Support Care 1:353–365. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1478951503030426

Al Daken LI, Ahmad MM (2018) The implementation of mindfulness-based interventions and educational interventions to support family caregivers of patients with cancer: a systematic review. Perspect Psychiatr Care 54:441–452. https://doi.org/10.1111/ppc.12286

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the family caregivers that participated in the study. This work was possible only because they gave their time and shared their experiences with us.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All the authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by Zavagli Veronica, Raccichini Melania, Ostan Rita, Ercolani Giacomo, and Franchini Luca. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Zavagli Veronica, and all the authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

Approval was obtained from the ethics committee of Area Vasta Emilia Centro of Emilia-Romagna Region (CE-AVEC). All procedures were performed in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments.

Consent to participate

Informed written consent was obtained from all participants included in the study.

Consent for publication

Informed written consent was obtained from all participants included in the study.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zavagli, V., Raccichini, M., Ostan, R. et al. Identifying the prevalence of unmet supportive care needs among family caregivers of cancer patients: an Italian investigation on home palliative care setting. Support Care Cancer 30, 3451–3461 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-021-06655-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-021-06655-2