Abstract

Purpose

Since South Korea’s 5-year policy of increasing National Health Insurance (NHI) coverage began in 2017, related pharmaceutical expenditures have increased by 41%. Thus, there is a critical need to examine society’s willingness to pay (WTP) for increased premiums to include new anticancer drugs in NHI coverage.

Methods

Participants aged 20–65 were invited to a web-based online survey. The acceptable effectiveness threshold for a new anticancer drug to be included in NHI coverage and the WTP for an anticancer drug with modest effectiveness were determined by open-ended questions.

Results

A total of 1817 respondents completed the survey. Participants with a family history of cancer or a higher perceived risk of getting cancer had significantly higher WTPs (RR [relative risk] = 1.17 and 1.21, both P = 0.012). Participants who agreed on adding coverage for new anticancer drugs with a life gain of 3 months had a higher WTP (RR = 1.70, P < 0.0001). These associations were greater among the employed and low-income groups. The adjusted mean of acceptable effectiveness for a new anticancer drug was 21.5 months (interquartile range [IQR] = 19.3 to 24.0, median = 21.9). The WTP for a new anticancer drug with a life gain of 3 months was $5.2 (IQR = 4.0 to 6.0, median = 4.6).

Conclusion

The unrealistic expectations in Korean society for new anticancer agents may provoke challenging issues of fairness and equity. Although Korean society is willing to accept premium increases, our data suggest that such increases would benefit only a small proportion of advanced cancer patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In South Korea, during the past 30 years, the National Health Insurance (NHI) program and its cancer policies, including those related to medical accessibility and costs, have protected beneficiaries from financial toxicity, the economic distress, including bankruptcy, which may result from the rapidly increasing cost burdens of cancer treatments. After the strengthening of NHI benefits in December 2009, most cancer patients who are NHI beneficiaries in Korea pay only 5% of the total medical expenses incurred by their cancer. In addition, medical aid includes approximately 3% of low-income or disabled individuals who do not pay an insurance premium for NHI and are provided medical services for cancer treatment without making copayments. The NHI and medical aid cover most medical services related to cancer in Korea, except for services that are uninsured due to their low cost-effectiveness or uncertain clinical benefits. Nevertheless, the rapid introduction of newly developed anticancer drugs has become a great challenge for the sustainability of the NHI, even though such drugs could improve the outcomes of cancer patients [1]. Although the NHI has introduced several measures, including cost-effective analyses as part of the process for approving newly developed anticancer drugs, the sky-rocketing costs still threaten the NHI’s sustainability. In August 2017, the South Korean government announced the beginning of a 5-year policy to strengthen NHI coverage, and increasing access to newly developed anticancer drugs is one of the major focuses of the policy [2, 3]. After the program, anticancer pharmaceutical expenditures in the NHI budget increased by 41%, from 0.9 billion United States dollars (USD) in 2016 to 1.3 billion USD in 2018 [4]. This rapid expansion of insurance coverage has inevitably increased the budgetary burden on the NHI, and to meet the expenses of the NHI, insurance contribution rates were increased by more than the average annual growth rate. The contribution rate will increase to 7.16% in 2022 according to the government plan [5].

Given that most newly developed anticancer drugs in recent decades generate modest survival benefits of a few months of life gain, there is a risk that drugs that are not cost-effective may be introduced rapidly [6]. Indeed, the ratio of NHI expenditures to income (%) increased from 93.3 in 2016 to 103.6% (fiscal deficit) in 2018 [7]. Thus, considering the financial sustainability of the NHI, there is a need to reconcile the financial sustainability of the NHI and the increasing demand for coverage. To provide balanced evidence for such policy making, the current study investigates the willingness to pay (WTP) an additional insurance premium if new anticancer drugs were approved for NHI coverage and the acceptable level of drug effectiveness for including that new drug in NHI coverage.

Methods

Study population

The data used in this study were collected via an online survey and were used to investigate the WTP an additional NHI premium to cover a newly developed anticancer drug. The study population included people with jobs in the age range 20–65 years, and we sampled the study population (7.5 people per 100,000) via stratified random sampling, controlling for sex, age, and region. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board, National Cancer Center of Korea, and written consent was waived for all study participants (NCC2020-0156).

Measurement

The current study has two main outcome variables. The first main outcome is the acceptable effectiveness threshold, which was defined based on an open-ended question about the minimum effectiveness level needed for a drug to be newly registered in the NHI. The participants were asked, “How much should a new, highly expensive drug be proven to extend life in order for it to be supported and reimbursed by the National Health Insurance?” The second outcome was the WTP for the introduction of a new anticancer drug with a life gain of 3 months into the NHI reimbursement system, which would impose a substantial burden on the system. The participants were asked, “How much extra are you willing to pay for a new drug to be reimbursed by the NHI, given that it can extend the life of 200,000 cancer patients for another three months?” Throughout the study, KRW were converted into USD ($1 = 1200 KRW). The collected independent variables were as follows: general characteristics (sex, age, education level, area of residence, number of family members, and marital status), socioeconomic status (job, individual/household income, NHI or medical aid, and private insurance coverage), and risk of cancer (individual/family history of cancer and perceived risk of getting cancer). Age was categorized into groups of 10 to 15 years: 20–29, 30–39, 40–49, and 50–65. Area of residence was classified into capital areas (Seoul and Gyeong-Gi), metropolitan areas, and others. Education level consisted of middle school, high school, and above college, and job status was defined as employed or self-employed to take individuals’ social status into account. Household income was measured by the following survey question: “What is your average household income (including that of members who live with you)?” In this question, household income was defined on a monthly basis and adjusted by the number of household members. If the respondent answered that people had private insurance in response to the question on insurance availability, private insurance was defined as “present,” which could mean the respondent is sensitive to the economic burden of cancer management. The perceived risk of getting cancer was defined by whether the respondent thought he or she would get cancer in the next 10 years: “How likely do you think it is that you will get cancer in the next 10 years?” Details of the questionnaire for new anticancer drugs are described in the Supplementary information.

Statistical analysis

The characteristics of the study population were described using the frequencies and percentages of each categorical variable. To compare the means and standard deviations (SD) of acceptable effectiveness and WTP according to each categorical variable, analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed on the outcome variables. We defined outliers as those observations in the top and bottom 1% of the continuous variables, such as household income, acceptable effectiveness, and WTP. To consider the distribution of the outcome variables, we performed linear regression analysis with a gamma distribution and log link to explore the possible associations of acceptable effectiveness and WTP with the independent variables and interpreted the multiplicative changes as relative risk (RR) after exponentially transforming the coefficient. The means and distribution of the outcome variables were provided after controlling for the independent variables based on regression analysis. All statistical analyses were performed by using SAS version 9.4 (Cary, NC, USA). P values < 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Responses from a total of 1817 respondents (70% response rate) were used in this study after excluding outliers in terms of the continuous variables (n = 66). Table 1 shows the study population, and the outcome variables were described according to each independent variable. The mean acceptable effectiveness threshold for covering a new anticancer drug was 21.5 months (interquartile range [IQR] = 21.9 to 24.0, median = 19.2), and the mean WTP for an increased premium to cover an anticancer drug with a life gain of 3 months was $5.2 (IQR = 3.9 to 6.0, median = 4.7), which is approximately 6% of the current average monthly NHI premium (80.8 to 83.3 USD in 2020).

Table 2 shows the characteristics of the study population. Males and females were equally represented, and most respondents were more than 50 years old in this study. For socioeconomic status, most respondents had more than a college education (84.6%), and employment was more frequent than self-employment (92.5% vs. 7.5%). Approximately half of the participants had a household size of more than 3 persons (45.6%), and approximately half were married (59.5%). The average adjusted household income was $2215.90, and a quarter of participants (25.1%) had adjusted household incomes less than $1500. Regarding cancer history, 5.9% of people had a history of cancer, and 42.8% had a family history of cancer. Additionally, 19.9% of the people in the study population perceived themselves to be at risk of getting cancer.

The association between acceptable effectiveness and WTP was tested by linear regression analysis and is summarized in Table 3. The outcome variables were fitted to a gamma distribution, and the results were transformed into RR. The economic conditions and risks of cancer were generally associated with higher WTP but not with higher acceptable effectiveness thresholds. The acceptable effectiveness threshold was not associated with most independent variables. In contrast, a higher WTP to cover drugs with a life gain of 3 months was significantly associated with being male (1.15 times higher than for females), being of a younger age (1.30 times higher among those 20–29 years and 1.21 times higher among those 30–39 years than among those 50-65 years), having less education (1.28 times higher), not having private insurance (1.27 times higher), having a family history of cancer (1.17 times higher), and perceiving a higher risk of getting cancer (1.21 times higher). We observed a WTP that was 1.27 times higher in the employed group than in the self-employed group, which was statistically significant (P = 0.04). Participants who agreed with covering a new anticancer drug with a life gain of 3 months were more highly associated with a higher WTP (P < 0.0001).

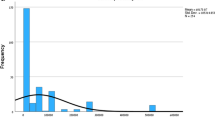

Figure 1 shows the adjusted values for (a) the acceptable effectiveness threshold for including a newly developed anticancer drug in NHI coverage and (b) the WTP for a newly developed anticancer drug with a life gain of 3 months. These values were calculated based on regression analysis controlling for general characteristics, socioeconomic status, and cancer risk. The adjusted mean of the acceptable effectiveness was 21.5 months (IQR = 19.3 to 24.0, median = 21.9), and the WTP for a new anticancer drug with a life gain of 3 months was $5.2 (IQR = 4.0 to 6.0, median = 4.6).

Discussion

Our study findings suggest that the acceptable effectiveness threshold for new anticancer drugs to be reimbursed by the NHI system is 21.5 months. The current study indicates that expectations within the whole society for the effectiveness of new anticancer agents are unrealistically high. For example, three-quarters of the general population responded that the effectiveness of a new anticancer drug to be included in NHI coverage should be at least 19 months. It is common that patients frequently hold unrealistic hopes for their prognosis or response to a new therapy [8]. Another study found that most patients with lung cancer expected to live for more than 2 years, even though the average length of survival is approximately 8 months [9]. On the other hand, it is striking that the proportion accepting an effectiveness threshold of less than 12 months was negligible. Therefore, it is apparent that this discrepancy could raise a debate on the low threshold for approval.

In South Korea, patients are responsible for only 5% of the costs of their approved treatment, and the remaining 95% of the cost is transferred to society members. However, the expectations among the general population have not been well investigated because cancer patients are usually responsible for the cost of their cancer therapy. Currently, the general population has been marginalized from the discussion of the drug approval process, although they are responsible for 95% of the cost burden. Therefore, greater efforts are needed to enhance transparent communication about the effectiveness of new anticancer drugs not only for patients but also for the general population. In addition, it should be noted that low thresholds for new drug approval for expensive drugs have been ethically criticized [6, 10]. Therefore, there should be a clear and agreeable efficacy threshold for drug approval. The most commonly cited cost-effectiveness thresholds are those based upon a country’s per capita gross domestic product (GDP) [11]. In 2005, the World Health Organization’s Choosing Interventions that are Cost-Effective project (WHO-CHOICE) suggested that interventions that avert the loss of one disability-adjusted life year (DALY) for less than the average per capita income are considered very cost-effective and that interventions that cost less than three times the average per capita income per DALY loss averted are still considered cost-effective. However, in the real world, there are many societies that are unable or unwilling to pay three times their per capita GDP, even if an intervention is assessed as cost-effective [12]. Therefore, society’s WTP should be carefully considered.

In our study, we found that the general population may be willing to accept a premium increase of 5.2 USD for covering new anticancer drugs with a modest efficacy of a 3-month life gain, which is almost 6% of the current contribution [5]. Considering that the recent premium increase of 6.7% in 2 successive years provoked critical opposition in South Korea, the WTP might be overestimated in the current study. Even if agreed upon, this increase would translate into 100.4 million USD per year. In addition, considering the WHO-CHOICE recommendation and the recent per capita GDP of South Korea, the cost-effectiveness threshold for a drug providing 3 months of life years gained should be 23,522 USD. Thus, all these crude assumptions suggest that only 5% of dying cancer patients would benefit from such an increase in NHI premiums. Therefore, although such a change is not realistic, such convergence may raise ethical issues of fairness and equity, considering that there may be many opportunities to spend resources on improving the health or quality of life for a far greater proportion of the general population.

This study has several notable limitations. First, only open-ended questions were used to estimate acceptable effectiveness thresholds instead of double-bounded dichotomous choice questions, which might have helped to mitigate bias [13, 14]. However, since double-bounded dichotomous choice questions have a lower response rate and a higher nonresponse/protest rate [15], we preferred open-ended questions for the current study. Second, the investigation was cross-sectional in nature, and the results of this study are not necessarily causal. Therefore, readers should be careful in interpreting the results. Third, the current survey only asked about the WTP for an anticancer drug with a benefit of a 3-month life gain but not about the WTP for other efficacies. Therefore, our results may not be valid in the case of extremely effective drugs. Fourth, the outcome variables may vary depending on the individual’s knowledge or expertise in the medical field. However, we could not collect information on characteristics such as type of job and could not adjust the related characteristics. Finally, the data were collected using an online panel survey (70% response rate). We excluded outliers in terms of the continuous variables such as WTP and acceptable effectiveness thresholds. Thus, this study may have biases concerning the representativeness and generalizability of the results.

Conclusion

The current study indicates that the expectations of society as a whole for the effectiveness of new anticancer agents are unrealistically high. This discrepancy between expectations and reality is a potential source of social conflict and may provoke challenging issues of fairness and equity. In contrast, society as a whole is willing to accept increased premium for covering a new drug even if that drug has only a modest effect. However, regardless of whether such an increase could be realized, our data suggest that it would benefit only a small proportion of patients. Thus, a societal consensus based on well-interpreted information and adequate communication should be developed on this issue. In addition, a clear cost-effectiveness threshold should be introduced for making decisions on the reimbursement and pricing of new cancer pharmaceuticals.

References

Kim H, Jang J, Sohn HS (2012) Anticancer drug use and out-of-pocket money burden in Korean cancer patients: a questionnaire study. Korean J Clin Pharm 22:239–250

Yoo SL, Kim DJ, Lee SM, Kang WG, Kim SY, Lee JH, Suh DC (2019) Improving patient access to new drugs in South Korea: evaluation of the national drug formulary system. Int J Environ Res Public Health 16:288. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16020288

Kim Y (2018) Moon Care: strategies and challenges. Public Health Aff 2:17–27

Ministry of Health and Welfare (2019) News & welfare services. 36M S. Koreans Received KRW 2.2T Worth of Healthcare Benefits. http://www.mohw.go.kr/react/al/sal0301vw.jsp?PAR_MENU_ID=04&MENU_ID=0403&CONT_SEQ=349994. Accessed 4 June 2020

National Health Insurance Service (2019) NHI program - contributions. https://www.nhis.or.kr/static/html/wbd/g/a/wbdga0404.html. Accessed 4 June 2020

Wise PH (2016) Cancer drugs, survival, and ethics. BMJ 355:i5792. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i5792

National Health Insurance Service (2018) National Health Insurance finance annual report. http://kosis.kr/statHtml/statHtml.do?orgId=350&tblId=TX_35001_A023&conn_path=I2. Accessed 4 June 2020

Donovan RJ, Carter OB, Byrne MJ (2006) People’s perceptions of cancer survivability: implications for oncologists. Lancet Oncol 7:668–675. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70794-X

Huskamp HA, Keating NL, Malin JL, Zaslavsky AM, Weeks JC, Earle CC, Teno JM, Virnig BA, Kahn KL, He Y, Ayanian JZ (2009) Discussions with physicians about hospice among patients with metastatic lung cancer. Arch Intern Med 169:954–962. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2009.127

Wise PH (2016) Author’s reply to Dangoor and colleagues. BMJ 355:i6508. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i6508

World Health Organization (2001) Macroeconomics and health: investing in health for economic development. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/42435/1/924154550X.pdf. Accessed 4 June 2020

Zelle SG, Vidaurre T, Abugattas JE, Manrique JE, Sarria G, Jeronimo J, Seinfeld JN, Lauer JA, Sepulveda CR, Venegas D, Baltussen R (2013) Cost-effectiveness analysis of breast cancer control interventions in Peru. PLoS One 8:e82575. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0082575

Nosratnejad S, Rashidian A, Akbari Sari A, Moradi N (2017) Willingness to pay for complementary health care insurance in Iran. Iran J Public Health 46:1247–1255

Frew EJ, Whynes DK, Wolstenholme JL (2003) Eliciting willingness to pay: comparing closed-ended with open-ended and payment scale formats. Med Decis Mak 23:150–159. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272989X03251245

Reaves DW, Kramer RA, Holmes TP (1999) Does question format matter? Valuing an endangered species. Environ Resour Econ 14:365–383. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:100832062172

Funding

This study was funded by the National Cancer Center of Korea (2010230).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Sokbom Kang contributed to the study conception and design. Data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation were performed by Kyu-Tae Han, Ye Lee Yu, and Woorim Kim. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Kyu-Tae Han, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. Woorim Kim contributed to the review and editing of the manuscript. All authors read, revised, and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was waived from all individual participants included in the study. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the National Cancer Center, Korea (NCC2020-0156).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Han, KT., Yu, Y.L., Kim, W. et al. Is Korean society prepared for the financial burden of novel anticancer drugs? A survey of willingness to pay among National Health Insurance beneficiaries. Support Care Cancer 29, 6681–6688 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-021-06091-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-021-06091-2