Abstract

Purpose

Little evidence exists regarding the emetogenicity of chemotherapy in pediatric patients. This study describes the prevalence of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) in pediatric patients receiving etoposide plus ifosfamide over 5 days, a common pediatric regimen.

Methods

English-speaking, non-chemotherapy-naïve patients aged 4 to 18 years about to receive etoposide 100 mg/m2/day plus ifosfamide 1800 mg/m2/day over 5 days participated. Antiemetic prophylaxis was determined by each patient’s care team. Emetic episodes were recorded and nausea severity was assessed by patients beginning with the first chemotherapy dose, continuing until 24 h after the last chemotherapy dose (acute phase) and ending 7 days later (delayed phase). The proportion of patients experiencing complete acute CINV control (no nausea, no vomiting, and no retching), the primary study endpoint, was described. The prevalence of complete chemotherapy-induced vomiting (CIV) and chemotherapy-induced nausea (CIN) during the acute, delayed, and overall (acute plus delayed) phases; complete delayed and overall CINV control; and anticipatory CINV were also determined.

Results

Twenty-four patients participated; acute CINV was evaluable in 22. Most (75%; 18/24) received a 5-HT3 antagonist plus dexamethasone for antiemetic prophylaxis. Few (23%; 5/22) experienced complete acute CINV control. Complete acute CIV and CIN control were experienced by 57% (13/23) and 27% (6/22) of patients, respectively. Complete delayed CINV, CIV, and CIN control rates were 42% (8/19), 70% (14/20), and 42% (8/19), respectively.

Conclusions

Our findings support the classification of etoposide 100 mg/m2/day plus ifosfamide 1800 mg/m2/day IV over 5 days as highly emetogenic. This information will optimize antiemetic prophylaxis selection and CINV control in pediatric patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Despite recent advances in the prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV), these adverse effects remain prevalent and bothersome in pediatric cancer patients [1,2,3]. Emetogenicity, defined as the propensity of a drug to cause vomiting or retching, is the primary determinant of antiemetic prophylaxis. Clinical practice guidelines for the prevention of acute chemotherapy-induced vomiting (CIV) in children make recommendations based on whether the child is receiving highly, moderately, low, or minimally emetogenic chemotherapy [4]. Due to limitations in the available literature, it is not possible to classify the emetogenicity of even commonly administered chemotherapy regimens based on experience in pediatric patients. There are many gaps.

For example, protocols involving multiple-day treatment with ifosfamide and etoposide are considered to be the standard of care in many pediatric cancers including osteosarcoma and Ewing’s sarcoma [5]. In adults, ifosfamide < 2 g/m2/day is classified as moderately emetogenic (> 30 to 90% incidence of vomiting in the absence of prophylaxis) [6, 7] while etoposide is classified both as moderately emetogenic [6] and of low [7] emetic risk (10 to 30% incidence of vomiting in the absence of prophylaxis). Using the method for adjusting emetogenicity classification for combination chemotherapy regimens described by Hesketh et al., 60 to 90% of adult patients receiving etoposide plus ifosfamide without antiemetic prophylaxis would be expected to vomit [8]. A recent pediatric clinical practice guideline [4] classified the combination of etoposide ≥ 60 mg/m2/dose IV daily for 5 days and ifosfamide ≥ 1200 mg/m2/dose IV daily for 5 days as highly emetogenic based on the experience of only five children [9]. The low quality of published pediatric experience and the discrepancy between the pediatric and adult classifications of this regimen’s emetogenicity lead to uncertainty. Furthermore, the prevalence of delayed vomiting, acute nausea, and delayed nausea has never been described in pediatric patients receiving this regimen.

We undertook this prospective, observational study to describe the proportion of pediatric patients aged 4 to 18 years who experienced complete CINV control (no vomiting, no retching, and no nausea) in the acute phase while receiving etoposide 100 mg/m2/day plus ifosfamide 1800 mg/m2/day over five consecutive days, a regimen commonly used in solid tumor pediatric treatment protocols. The prevalence of CINV in the delayed and overall phases and of CIV and chemotherapy-induced nausea (CIN) in the acute, delayed, and overall phases were also described in these patients.

Methods

This prospective observational study was approved by the Research Ethics Board at The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, Canada.

Patients

English-speaking children 4 to 18 years of age about to receive etoposide 100 mg/m2/day plus ifosfamide 1800 mg/m2/day over 5 days were eligible to participate. Children with physical or cognitive impairments that precluded use of the Pediatric Nausea Assessment Tool [10] (PeNAT) were excluded. The patient or their parent provided informed consent for the study. The assent of patients who were unable to provide consent was obtained when appropriate. Each child participated in the study only once. Study participation did not influence a patient’s antiemetic regimen; CINV prophylaxis and breakthrough antiemetic agents were administered as prescribed by the patient’s care team.

Data collection

Patients were recruited intermittently from August 2010 to December 2017 based on the availability of study team members. The study period began immediately prior to the first chemotherapy dose of the child’s chemotherapy block, continued 24 h after the last chemotherapy dose (acute phase), and ended 168 h (7 days) later (delayed phase).

The following information was collected from the patient’s health record: age, sex, cancer diagnosis, date of cancer diagnosis, weight, height, chemotherapy protocol, receipt of prior chemotherapy, all chemotherapy doses given during the study period, and all antiemetics given during the study period. In addition, we also asked the patient and their parent/guardian if they had experienced nausea and vomiting within 24 h prior to chemotherapy or had a history of motion sickness.

Structured diaries were used to collect data regarding the child’s experience with CINV, and their use has been described elsewhere [11]. Importantly, each patient was asked to assess the severity of their present nausea using the PeNAT at least two times a day (morning and bedtime) as well as every time they felt nauseated or the parent/guardian believed that the patient might be nauseated. The number of vomiting episodes noted by the patient or parent was verified against the nursing flow sheets, when possible. If the number of vomiting episodes recorded on the flow sheet differed from those recorded on the diary, the larger of the two numbers was used for analysis. When possible, all diary pages completed when the patient was an inpatient at the hospital were collected prior to discharge. Diary pages that were completed in the outpatient period were returned either by mail or in person to a study investigator. Families were contacted by a study team member up to three times during the study period to remind them to complete and return the diaries. If diaries were not returned, the number of vomiting episodes were ascertained from the nursing flow sheets. In cases where diaries were not returned and vomiting episodes were not able to be ascertained from nursing flow sheets, the patient was excluded from data analysis. In cases where only a portion of the diaries were returned for any given phase, the highest reported PeNAT score available was used for analysis.

Definitions

Vomiting was defined as expulsion of any stomach contents by the mouth. Retching was defined as an attempt to vomit that was not productive of any stomach contents. A chemotherapy block was defined as a consecutive set of 5 days where chemotherapy was administered daily. The acute phase was defined as the time starting from the administration of the first dose of chemotherapy and continuing until 24 h after administration of the last dose of chemotherapy in a chemotherapy block. The delayed phase started at the end of the acute phase and continued for a maximum of 168 h (7 days) or until the start of the next chemotherapy block. The anticipatory phase was defined as the 24-h period prior to receiving the first dose of chemotherapy of the block. Definitions of CINV, CIV, and CIN control are presented in Table 1. PeNAT scores of 1 through 4 reflected no, mild, moderate, and severe nausea respectively. Diary completion rate was defined as the proportion of completed diary pages returned to the study investigator.

Statistical analysis

A sample size of convenience of 30 patients was chosen as this number was thought to be feasible and would provide information from patients of varied ages and sex. The primary study endpoint was complete CINV control (no vomiting, no retching, and no nausea (maximum PeNAT score = 1)) in the acute phase. CINV control in the delayed phase and CIV and CIN control during the acute, delayed, and overall phases were secondary outcomes. The proportion of patients experiencing various levels of CINV, CIV, and CIN control was calculated.

Results

Patient characteristics and diary completion

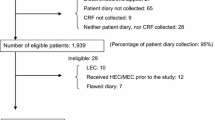

Twenty-four patients consented to participate in the study. A pragmatic decision was taken to close the study to recruitment before reaching the target sample size of 30.

Twenty-two patients were evaluable for acute phase CINV and CIN control while 23 patients were evaluable for acute phase CIV control. Analysis of delayed and overall phase CINV, CIV, and CIN control was possible in 19, 20, and 19 patients, respectively. Characteristics of the participants are summarized in Table 2.

The diary completion rate was 85% (123/144 days) in the acute phase, 79% (133/168 days) in the delayed phase, and 82% (256/312) overall. Two patients returned no diary pages; however, acute phase vomiting was assessed for one of these patients based on the nursing flow sheets. Nausea assessment in the acute phase for two patients was based on four returned diary pages, and for one patient, one completed diary page. Three patients returned no diary pages in the delayed phase. CIV was assessed using nursing flow sheets for one of these patients.

Antiemetic prophylaxis administered

All patients received a 5-HT3 receptor antagonist (ondansetron: 18 patients; granisetron: 4 patients; or palonosetron: 2 patients) on a scheduled basis during the acute phase. Most patients (83%; 20/24) also received dexamethasone on a scheduled basis in doses ranging from 4.3–15.6 mg/m2/day divided into one or two doses. Nabilone was ordered as a scheduled medication for 4 patients.

Antiemetic administration in the delayed phase was evaluated solely based on returned diaries. Almost half of the patients (47%; 9/19) received no antiemetics, scheduled or on a rescue basis, during the delayed phase. The other half of patients (53%; 10/19) received ondansetron or granisetron on at least 1 day in the delayed phase and of these, six patients received antiemetics on all 7 days of the delayed phase. Ondansetron or granisetron was given in combination with dexamethasone (two patients) or nabilone (three patients) on at least 1 day of the delayed phase.

CINV control

CINV, CIV, and CIN prevalence is presented in Table 3. CINV, CIV, and CIN control rates based on antiemetic prophylaxis received are presented in Table 4.

Few patients (23%; 5/22) experienced complete acute phase CINV control. This rate was primarily driven by the low rate of complete acute phase CIN control (27%; 6/22) as more than half of patients (13/23; 57%) reported complete acute phase CIV control. The pattern of low CIN control and higher CIV control was also observed in the delayed and overall phases. The median maximum PeNAT scores reported in the acute and delayed phases were 3 (range 1–4) and 2 (range 1–4), respectively.

Five patients (21%) experienced anticipatory CINV. Two patients experienced both anticipatory nausea and vomiting while three patients experienced anticipatory nausea alone.

Discussion

Less than one quarter (23%) of patients who received etoposide 100 mg/m2/day plus ifosfamide 1800 mg/m2/day for 5 days at our institution experienced complete acute phase CINV control. This finding was driven primarily by our observation that the majority of patients experienced nausea during both the acute and delayed phases. It is also important to acknowledge that, while the majority of our patients experienced complete CIV control, almost 20% experienced uncontrolled acute phase vomiting.

During the study period, institutional acute CIV prophylaxis guidelines were available and were incorporated into pre-printed or electronic order sets. These guidelines were adapted from pediatric clinical practice guidelines [12, 13]. A 5-HT3 antagonist plus dexamethasone was recommended for patients receiving ifosfamide plus etoposide. In 2008, aprepitant was also recommended for patients 12 years of age and older who were not planned to receive chemotherapy known or suspected to interact; in 2017, its recommended use was extended to children 6 months of age and older. The variability that we observed in the acute CIV prophylaxis administered likely reflects evolving evidence regarding the use of aprepitant in young children, the shift in perceptions of relative benefits and harms regarding the use of aprepitant and dexamethasone, and the health care team’s individualized response to patients who experienced refractory CIV.

Based on the algorithm used in a recent pediatric emetogenicity classification clinical practice guideline [4] and on the antiemetic prophylaxis that our patients received (Table 4), our findings support the classification of this regimen as highly emetogenic. That is, it is expected that more than 90% of patients who receive this chemotherapy would vomit if not given antiemetic prophylaxis. Our findings highlight the difficulty in applying the experience of adult patients directly to pediatric patients. Children may be inherently more susceptible to CIV than are adults or less responsive to antiemetic agents or they may receive more dose-intensive regimens. It is important to understand the emetic risk that chemotherapy presents to pediatric patients specifically so that antiemetic prophylaxis selection and CIV control can be optimized.

Antiemetic prophylaxis with a 5-HT3 antagonist plus dexamethasone resulted in complete control of acute CIV in 67% of our patients receiving etoposide 100 mg/m2/day plus ifosfamide 1800 mg/m2/day. It is clear that, in order to improve acute CIV control in pediatric patients receiving this chemotherapy regimen, different strategies than this combination are required. According to current pediatric clinical practice guidelines, the receipt of highly emetogenic chemotherapy warrants administration of triple antiemetic prophylaxis with a 5-HT3 antagonist, dexamethasone, and aprepitant [7, 13, 14]. However, due to concerns regarding interactions between aprepitant and both ifosfamide and etoposide, aprepitant was not given to our patients [15]. Further, almost one-fifth of study participants received antiemetic prophylaxis with a 5-HT3 antagonist alone. The reasons that dexamethasone was withheld from these patients are unclear.

In our study, the proportion of patients who experienced complete CIN control was even lower than those who experienced complete CIV control. No system for classifying the risk of nausea of chemotherapy exists, and it is not known if HEC also brings with it a high risk of nausea. Antiemetic agents cannot be assumed also to have antinauseant properties, and as has been noted in adult patients, the profile of CIN is perhaps more able to be appreciated once CIV control has improved.

The main strengths of our study are the focus on CINV as the primary study aim, its prospective approach to gathering objective and subjective information about the CINV experience of pediatric patients, and the use of a validated pediatric nausea assessment tool. Nevertheless, although our study is over fourfold larger than the other pediatric study describing the emetogenicity, the generalizability of our findings may be limited by sample size and by the long time period over which patients were recruited. In mid-2014, administration of ifosfamide plus etoposide was moved primarily from the inpatient unit to the outpatient clinic. Recruitment was constrained by this change and, we speculate, the reluctance of patients and families to take responsibility for CINV diary completion while commuting between home and clinic. In addition, it is possible that our sample was subject to selection bias since patients who elected to participate may have been more likely to have experienced CINV in the past. Similarly, we were not able to purposively sample patients to balance the effect of recently identified risk factors for CIV and CIN (e.g., age, race, antiemetic agents) in pediatric patients [16, 17]. Furthermore, we relied heavily on the patient and their parent for data collection. This was mitigated by verifying vomiting episodes noted on the diary against the nursing flow sheet and by contacting parents and patients frequently to remind them to complete the diary. Ideally, an electronic version of the CINV diary that is compatible with mobile devices should be offered to patients and families in future studies evaluating CINV so as to improve data integrity.

In this prospective study, few pediatric patients experienced complete CINV control. Clearly, this must be improved. Provision of clinical practice guideline–consistent antiemetic prophylaxis is likely to increase the proportion of children who experience complete acute CINV control [18], but new antiemetic and antinauseant interventions are also required. Evaluations of the extent to which aprepitant or fosaprepitant influences exposure to specific chemotherapy agents would facilitate the ability of clinicians to weigh the risks and benefits of their use in patients receiving chemotherapy suspected to interact. Pediatric studies evaluating the efficacy and safety of interventions such as rolapitant, a neurokinin-1 antagonist with reduced risk of drug interactions [19], olanzapine, and others are warranted as is a pediatric clinical practice guideline regarding delayed CINV prophylaxis.

References

Dupuis LL, Milne-Wren C, Cassidy M, Barrera M, Portwine C, Johnston DL, Silva MP, Sibbald C, Leaker M, Routh S, Sung L (2010) Symptom assessment in children receiving cancer therapy: the parents’ perspective. Support Care Cancer 18(3):281–299. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-009-0651-1

Hinds P, Gattuso J, Billups C, West N, Wu J, Rivera C, Quintana J, Villarroel M, Daw N (2009) Aggressive treatment of non-metastatic osteosarcoma improves health-related quality of life in children and adolescents. Eur J Cancer 45(11):2007–2014

Lorusso D, Bria E, Costantini A, Di Maio M, Rosti G, Mancuso A (2017) Patients’ perception of chemotherapy side effects: expectations, doctor-patient communication and impact on quality of life - an Italian survey. Eur J Cancer Care 26:e12618. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecc.12618

Paw Cho Sing E, Robinson P, Flank J, Holdsworth M, Thackray J, Freedman J, Gibson P, Orsey A, Patel P, Phillips B, Portwine C, Raybin J, Cabral S, L S DL (2019) Classification of the acute emetogenicity of chemotherapy in pediatric patients: a clinical practice guideline. Pediatr Blood Cancer 66(5):e27646. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.27646

Reed DR, Hayashi M, Wagner L, Binitie O, Steppan DA, Brohl AS, Shinohara ET, Bridge JA, Loeb DM, Borinstein SC (2017) Treatment pathway of bone sarcoma in children, adolescents, and young adults. Cancer 123(12):2206–2218

Ettinger D, Berger M, Aston J, Barbour S, Bergsbaken J, Brandt D, al E (2018) NCCN Guidelines Version 3.2018 Antiemesis. NCCN. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/default.aspx#supportive. Accessed 28 Jan 2019

Hesketh P, Kris M, Basch E, Bohlke K, Barbour S, Clark-Snow R, Danso M, Dennis K, Dupuis L, Dusetzina S, Eng C, Feyer P, Jordan K, Noonan K, Sparacio D, Somerfield M, Lyman G (2017) Antiemetics: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline Update. J Clin Oncol 35(28):3240–3261. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2017.74.4789

Hesketh PJ, Kris MG, Grunberg SM, Beck T, Hainsworth JD, Harker G, Aapro MS, Gandara D, Lindley CM (1997) Proposal for classifying the acute emetogenicity of cancer chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 15:103–109

Cohen I, Zehavi N, Buchwald I, Yaniv Y, Goshen Y, Kaplinsky C, Zaizov R (1995) Oral ondansetron: an effective ambulatory complement to intravenous ondansetron in the control of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in children. Pediatr Hematol Oncol 12:67–72

Dupuis LL, Taddio A, Kerr EN, Kelly A, MacKeigan L (2006) Development and validation of a pediatric nausea assessment tool (PeNAT) for use by children receiving antineoplastic agents. Pharmacotherapy 26:1221–1231

Vol H, Flank J, Lavoratore S, Nathan P, Taylor T, Zelunka E, Maloney A, Dupuis L (2016) Poor chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting control in children receiving intermediate or high-dose methotrexate. Support Care Cancer 24(3):1365–1371. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-015-2924-1

Dupuis LL, Boodhan S, Holdsworth M, Robinson PD, Hain R, Portwine C, O’Shaughnessy E, Sung L (2013) Guideline for the prevention of acute nausea and vomiting due to antineoplastic medication in pediatric cancer patients. Pediatr Blood Cancer 60:1073–1082

Patel P, Robinson P, Thackray J, Holdsworth M, Gibson P, Orsey A, Portwine C, Freedman J, Madden J, Phillips R, Sung L, Dupuis L (2017) Guideline for the prevention of acute chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in pediatric cancer patients: a focused update. Pediatr Blood Cancer 64:e26542. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.26542

Dupuis L, Sung L, Molasiotis A, Orsey A, Tissing W, van de Wetering M (2017) 2016 updated MASCC/ESMO consensus recommendations: prevention of acute chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in children. Support Care Cancer 25(1):323–331. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-016-3384-y

Patel P, Leeder J, Piquette-Miller M, Dupuis L (2017) Aprepitant and fosaprepitant drug interactions: a systematic review. Br J Clin Pharmacol 83(10):2148–2162. https://doi.org/10.1111/bcp.13322

Dupuis L, Sung L, Tomlinson G, Pong A, Bickham K (2018) Potential factors influencing the incidence of chemotherapy-induced vomiting (civ) in children receiving emetogenic chemotherapy: a pooled analysis [abstract]. Pediatr Blood Cancer 65:eS33

Dupuis LL, Tamura RN, Kelly KM, Krischer JP, Langevin A-M, Chen L, Kolb EA, Ullrich NJ, Sahler OJZ, Hendershot E, Stratton A, Sung L, McLean TW (2019) Risk factors for chemotherapy-induced nausea in pediatric patients receiving highly emetogenic chemotherapy. Pediatr Blood Cancer 66(4):e27584. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.27584

Gilmore JW, Peacock NW, Gu A, Szabo S, Rammage M, Sharpe J, Haislip ST, Perry T, Boozan TL, Meador K, Cao X, Burke TA (2013) Antiemetic guideline consistency and incidence of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in US community oncology practice: INSPIRE Study. J Oncol Pract 10:68–74. https://doi.org/10.1200/jop.2012.000816

Heo Y-A, Deeks ED (2017) Rolapitant: a review in chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Drugs 77(15):1687–1694

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the patients and families who generously agreed to participate in this study. We are also grateful to Ms. Sheliza Moledina, Mr. Calvin Liu, and Ms. Jocelyne Volpe for assistance during the study and to Ms. Nusheen Rostayee for administrative assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

This prospective observational study was approved by the Research Ethics Board at The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, Canada. The patients or their parent provided informed consent for the study. The assent of patients who were unable to provide consent was obtained when appropriate.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Patel, P., Lavoratore, S.R., Flank, J. et al. Chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting control in pediatric patients receiving ifosfamide plus etoposide: a prospective, observational study. Support Care Cancer 28, 933–938 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-019-04903-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-019-04903-0