Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate primary care physicians’ (PCPs) role in survivorship care of older breast cancer survivors, their experiences and opinions of survivorship care plans (SCPs), and suggestions for improving care coordination and facilitation of SCPs among older (≥ 65 years) breast cancer survivors.

Methods

A web-based questionnaire was completed individually by PCPs about their training and what areas of survivorship they address under their care. A subset of survey participants were interviewed about survivorship care, care coordination, and the appropriateness and effects of SCPs on older breast cancer survivors’ outcomes.

Results

Physician participants (N = 29) had an average of 13.5 years in practice. PCPs surveyed that their main role was to provide general health promotion and their least common role was to manage late- and/or long-term effects. Semi-structured interviews indicated that the majority of PCPs did not receive a SCP from their patients’ oncologists and that communication regarding survivorship care was poor. Participants’ suggestions for improvements to SCPs and survivorship care included regular communication with oncologists, delegation from oncologists regarding roles, and mutual understanding of each other’s roles.

Conclusion

PCPs indicated that survivorship care and SCPs should be improved, regarding communication and roles related to their patients’ survivorship. PCPs should assume an active role to enhance PCP-oncologist communication. Future research in PCPs’ role in survivorship care in a broad, diverse cancer survivor population is warranted.

Implications for cancer survivors

More attention needs to focus on the importance of PCPs, as they are an integral part of dual management for older breast cancer survivors post-treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Advancements in cancer treatments, coupled with the aging of the population, have resulted in women aged 65 years and older accounting for more than half of the 3.1 million US breast cancer survivors [1, 2]. Addressing survivorship complexities among this large, growing population requires a comprehensive approach considering recommended follow-up care, managing multi-morbidity and medications, deciphering between age- or cancer-related physical and mental symptoms, and coordinating care from multiple physicians [3, 4].

Survivorship care plans (SCPs) may or may not improve existing and potential survivorship issues experienced by breast cancer survivors after cancer treatment [5]. In addition to collaboration with patients, SCPs should also be coordinated with multiple healthcare providers including the survivor’s primary care physician (PCP) [6]. Despite the growing consensus of the importance of PCPs in survivorship care, research examining PCPs’ experiences and opinions regarding survivorship care and survivor outcomes under their care is limited [7,8,9,10,11].

Current research regarding SCPs has mainly focused on the lack of and/or difficulty of care coordination between PCPs and oncologists [11,12,13,14,15]. A recent systematic review found poor and delayed communication between PCPs and oncologists, oncologists’ and PCPs’ uncertainty regarding the knowledge of PCPs to provide care, and discrepancies between PCPs and oncologists regarding roles and expectations [14]. Despite their significant role in survivorship care, previous research has also found that PCPs report feeling unprepared to provide survivorship care as detailed in the SCPs [16]. Bober and colleagues [17] found that 82% of PCPs felt that guidelines for cancer survivors are not well-defined and that they are inadequately prepared and trained in cancer survivorship. Taken together, the current survivorship care for older breast cancer survivors is lacking in terms of care coordination, use and communication of SCPs, PCP and patient confidence in PCP training, and roles in survivorship care. Thus, this pilot study sought to examine PCPs’ role in survivorship care of older (≥ 65 years) breast cancer survivors, their experiences and opinions of SCPs, and suggestions for improving care coordination and facilitation of SCPs among older breast cancer survivors.

Methods

Potentially eligible PCPs affiliated with the Ohio University Medical Center and their contact information were identified through the Ohio State University Medical Center’s Pragmatic Clinical Trials Network database. To be eligible for the web-based survey and subsequent semi-structured interview, the PCPs must have been: (1) currently practicing in a primary care clinic; (2) treating older breast cancer survivors (women aged ≥ 65 years, diagnosed with any breast cancer subtypes at all stages) in their primary care practice; (3) willing and able to fill out a web-based survey in English.

A web-based survey of PCPs explored PCP training in survivorship care, confidence in addressing late effects of treatment and comorbidities, interactions with oncologists, and what areas of survivorship they address under their care. This question is based on ASCO’s recommendation on critical care plan components [18, 19] (which constitute SCPs) including cancer surveillance testing for recurrence and new primaries, significant late- and/or long-term effects, emotional or mental health, and healthy behaviors (e.g., diet, physical activity). PCP information on age, gender, race, ethnicity, years in primary care practice, medical specialty, time spent on patient care, and patient population characteristics (patient load, percentage of older patients, percentage of older breast cancer patients) was collected. Survey participants were mailed a $5 gift card for their time.

A subset of survey participants who were willing to participate in the interview phase of the project were contacted via phone or email. Semi-structured interviews focused on topics from the web-based survey and SCPs, particularly the appropriateness, clarity, content, and communication of SCPs, as well as ways to improve SCPs. PCPs were asked to share any comments they had about addressing these survivorship issues and outcomes and ideas for improving the care of older breast cancer survivors. Interviews were conducted in-person at a location of the participants’ choice, and interview participants received a $50 gift card for their time.

Analyses

Audio recordings of the interviews were transcribed verbatim by the interviewer. Two authors (JLKS, JD) trained in qualitative analysis read the interview transcripts and generated a list of themes that categorized the experiences shared by participants. All transcripts were coded using NVivo qualitative software and coded independently. Codes were then reviewed by authors, and discrepancies were resolved through consensus. A coding comparison was conducted in NVivo. All Kappa coefficients were < 0.85 and ranged from 0.86 to 0.97, indicating excellent interrater agreement. Descriptive statistics and frequency distributions were used to characterize research participants’ demographic and clinical characteristics. Quantitative analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics 23.

Results

Out of the 100 potentially eligible PCP participants within the Ohio State University Medical Center’s Pragmatic Clinical Trials Network, 29 completed the online survey and 10 participated in the semi-structured interview.

Survey results

Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of the PCP sample. Approximately one-third (43.5%) of the sample reported “a little” training and another 34.8% reported “moderate” training regarding cancer and treatment effects. Only 36.3% of PCPs reported feeling “confident” or “very confident” about evaluating and managing late effects of cancer treatment among older breast cancer survivors. In terms of receipt of SCPs, 36.4% and 36.4% of participants reported they received SCPs “none of the time” and a “little of the time”, respectively. The frequency of contact initiated by PCPs to their patients’ oncologist was limited as 50% reported “a little of the time” and 18.8% reported “none of the time”. Table 2 shows the prevalence of cancer survivorship issues and outcomes, as determined by SCPs, that PCPs regularly addressed under their care.

Semi-structured interview results

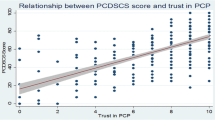

Several themes were discussed about the PCP role in the care of cancer survivors, communication with oncologists, SCPs knowledge and receipt and care coordination related to survivorship care, and areas of improvement of SCPs and survivorship care. Figure 1 presents a word cloud of the most common relevant words used in these interviews.

PCP role in the care of cancer survivors

The PCPs were concerned about the vagueness of their role regarding the care of cancer survivors. For example, one PCP said they were “Not really sure what my role is” and “Where do I fit in? Sort of like, what should I do?” Often, they expressed frustration at the vagueness of patient transfer of care back to them after the completion of initial treatment. A PCP said, “It is the ending of the oncologist’s role and the main caregiver and they’re transferring patients back to me when things get a little bit lost.” Similarly, one PCP said, “What I need is a note that says we are turning her back over to you for care, we’d like to have a chest x-ray done every year, we’d like to have these blood tests done every three months, if this, send them back to me.” Another remarked, “I feel like I am sort of a sphere operating all by myself and the cancer folks are operating all by themselves, and that doesn’t seem like a very smart way to address things.” Lastly, the PCPs did mention that they defer to the oncologists, despite having a closer relationship with their patients. One stated, “I’ve had people who do not do whatever they’re supposed to do until they’ve run it past me first, like you’re so sweet, definitely do what the cancer doctor says.”

Two PCPs felt that they knew their role regarding treatment of cancer survivors. Regarding the treatment of older breast cancer survivors, a PCP said, “My main role is trying to screen, effectively” and another stated, “I have a long-term relationship with people, so what I try to do when I’m ordering tests is tell them what the worst-case scenario might be when the results come in so I sort of buffer things a bit.”

PCPs regularly expressed how their role is secondary in relation to oncologists. One PCP stated, “Often times what you’ll find is that oncologists take on many things I do in primary care when their treatment is affecting those primary care kind of things.” Another mentioned, “They tend to claim the ownership of the cancer treatment.” Many felt intimated in their perceptions of and interactions with oncologists. For example, a PCP said, “…because it’s oncology and I wouldn’t dare tread on their toes.” Another mentioned their limited availability to discuss patient issues saying, “Oncologists being big brains, they’re often at conferences or whatever.” A similar attitude was observed among the patients. One PCP mentioned, “They [patients] come in fearful of the oncologists even knowing they’re here [PCP office]. They feel like it’s such a no-no.” Another stated, “I think they’re [patients] sort in awe of the oncologist.”

Communication with oncologists

The communication between PCPs and oncologists varied based on mode and individual. However, the majority of PCPs used words and phrases such as “one-directional”, “asynchronous”, “not great”, “sparse”, and “no communication”. Many felt that communication from oncologists are “…definitely not integrative with the primary care.”

Several PCPs mentioned a difference in personal communication and messages via electronic medical record (EMR), a seemingly preferred method of oncologists. One PCP stated, “I think they [oncologists] are very good at sending me their letters [via EMR], but they never reach out to me on a personal level… I don’t feel like that comes back my way.” Another said, “I do not think it [20] has happened without me reaching out first about something.” However, some did mention the use of internal paging systems and how it facilitated communication. Those PCPs did mention that “it’s a function of being in an academic setting” and they “haven’t had trouble” in communicating internally with oncologists. However, the response and real-time communication from oncologists to the PCPs varied. For example, one PCP said, “I can usually get an oncologist on the phone within 30 minutes” while another stated, “Within two days, maybe longer.” Variability in response was explained, “I think that depends on the oncologist, you have some people that you’ve worked with and know you can send them a note and you’ll get a response back quickly.”

SCPs knowledge and receipt and care coordination related to survivorship care

SCP knowledge and receipt was not common among PCPs. Knowledge of SCPs was minimal and participants’ rated their knowledge as “no knowledge”, “just when I got your [study] email”, and “I don’t know”. Furthermore, the majority of PCPs said they do not receive them at all or rarely. For example, a PCP said, “Electronically, I’ve gotten two within the last five years.” Likewise, one PCP stated, “Not at all. Tells you have many I have gotten.” Reasons as to why they did not receive SCPs centered on the lack of communication and knowing where to find them. One PCP mentioned, “…they might be in the chart and I could track them down.” Lastly, their involvement in the development of SCPs, as encouraged by the Institute of Medicine [21], was non-existent. PCPs said they were “Never a part of it” and “Never made in conjunction with me.” A potential reason for the absence of PCPs during SCP development was described by a PCP: “Time-wise or logistics-wise, PCPs who are almost never in the same building as oncologist are going to be limited in their ability to do that kind of planning.”

Among the minority of PCPs (n = 2) that did receive SCPs, the perceptions of the SCP format were positive and wished, “I had it for all of my patients” and “for everybody to have this kind of plan.” One PCP received a SCP from an oncologist a day prior to the interview and while examining it stated, “It’s nice, it’s got her PCP, reconstructive surgeon, gynecologist, dermatologist, treatment summary, so this a nice reminder. This is the first one of these I have ever seen.” Despite the positive feedback, the lack of time to review and knowledge of use were barriers. A PCP stated, “I’m embarrassed to tell you I have never read it [SCP]. I think when I told them [the oncology department] that, they were a little concerned…The intention was to coordinate but no one is reading it and it just comes down to the fact that there isn’t enough time and there is so much information coming at us.” Regarding the lack of consistent knowledge and subsequent use of SCPs, a PCP commented, “Nobody knows what it [SCP] is, it’s used for lots of different things”. A PCP described the multilevel issues associated with SCPs and their lack of knowledge and receipt, “That’s why we can’t get it together, we can’t seem to collectively, not only figure out what is a SCP, what is the definition of a SCP, but how is it utilized toward better patient care, where do we put it [in EMR], and who gets to co-manage it and edit it.”

Improvements to SCPs and survivorship care

Improvements for content and mode of communication of SCPs were discussed. The group was split among those who encouraged much detail while others did not want everything listed in the SCP. For example, a PCP said, “I really don’t think they should list everything that has ever happened to them. I think they should list current complications of their cancer, cancer treatment, and symptoms. I think it should list the planned visits with the oncologist.” Conversely, one PCP stated, “I almost don’t count them [SCPs] as care plans because they didn’t contain enough specifics for me.”

Despite their preference regarding the amount of information within SCPs, participants did want to be kept informed of SCPs and their expected roles of implementing SCPs. One PCP stated, “Number one it [SCP] should be sent to me, but number two I need to know where it is in the system, and be able to update it, or at least go back and look at it if that’s what I need to do.” Participants preferred delegation of roles, based on the SCPs, from the oncologists. One PCP said, “The more specifics you include on what you want when you want it, who is gonna do it, and what complications to look out for, the happier I am.” Likewise, a PCP commented, “...what would be helpful is the typical time course of follow-up. And then ongoing screening that either they’re going to do or they think I should do.”

In order to facilitate these suggestions, PCPs expressed that mutual understanding of each other’s roles in cancer survivorship is needed. A PCP remarked, “I think it’s because we’re looking at the same thing from two different perspectives.” Another said, “That’s what a health system needs, it has to have a common understanding.” In order to resolve this disconnect in understanding roles regarding survivorship care, a PCP wished, “They [oncologists] could come with more for a day and hear the same stories that I do. And so, they could almost get some education on the other perspective.”

Another area of improvement was the distribution of SCPs to patients through patient portals and hard copies at clinic visits. A PCP mentioned the importance of information organization for patients, “Personally, I would just break it down chronologically, so here’s what needs to happen for the rest of your life versus just the next few years.” Another said, “I would suggest that its [SCP] just copied into a MyChart [medical system patient portal] message and it be messaged to them, so they can access it easily as well.”

Discussion

This study sought to examine PCPs’ role in survivorship care of older breast cancer survivors, their experiences and opinions of SCPs, and suggestions for improving SCPs and survivorship among older breast cancer survivors. Survey results indicated that PCPs were responsible for general health promotion as typically seen in their regular practice and as outlined in the ASCO SCPs [19]. Interestingly, less than 30% of PCPs reported being responsible for the identification and management of late- and/or long-term effects, as directed by the American Cancer Society/ASCO breast cancer survivorship care guideline [22]. A potential reason for this low rate may be attributed to the lack of training regarding these effects coupled with the oncologist taking on this responsibility. Previous studies have found PCPs consistently report the need for more training in cancer survivorship [17, 23]. A recent article by Nekhlyudov and colleagues [24] encouraged additional education and training, such as oncogeneralist training [25], for PCPs extending beyond the cancer survivorship core competencies. Oncogeneralists could help to address PCP knowledge and training gaps, increasing collaborative care efforts such as dual management, and ultimately improving patient late- and/or long-term effects [24].

Reported electronic receipt and knowledge of SCPs among PCPs was low in this study. However, 2017 registry data from [BLINDED] found 203 of the 286 older breast cancer patients, who were eligible for a SCP, did receive a SCP. These high rates of SCP receipt among older breast cancer patients, yet low numbers of PCPs reporting receipt of SCP, demonstrates a disconnect within the transition of care. This low reported receipt of SCPs among the PCPs corresponds with previous studies [8, 26] that have found less than half of PCPs received a SCP from oncologists.

There was variation regarding the preferred amount of information contained within the SCP. Some PCPs preferred as much information as possible while others felt that they wanted a concise plan. Previous studies [9, 26, 27] have indicated that concise plans are preferred among PCPs. Succinctness is important; however, a comprehensive approach is needed, such as the inclusion of comprehensive geriatric assessments [28], to fully identify and address the complexity of survivorship care for older breast cancer survivors.

Lack of communication of SCPs and uncertainty of roles were a major theme. Results indicated that the communication between oncologists and PCPs was poor, in particular, regarding the expectations of PCP role in cancer survivorship, corroborating with the current literature [12, 14, 29]. Cheung et al. [11] found high discordances among PCPs and oncologists in perceptions of their own roles for survivorship care. This confusion was also observed among patients who lacked clarity on the relative roles of PCPs and oncologists as they transitioned out of active cancer treatment to survivorship. The current study also found that PCPs were willing to take a secondary role in survivorship care as long as they were informed of their role by the oncologists.

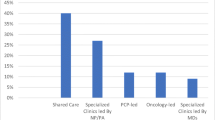

A potential reason for PCP confusion of their roles may due to the different models of survivorship care delivery (see Fig. 2). Furthermore, three national models have emerged at Commission on Cancer-accredited centers: (1) Consultative oncology specialist, (2) Longitudinal specialized survivorship clinic, and (3) Oncology-based survivorship care. None of these integrate PCPs into survivorship care [32]. Shared care models for delivering survivorship care have been promoted as a strategy to meet the care needs of cancer survivors [33]. A crucial component of this model is the provision of SCPs from oncologists to PCPs and periodic communication between providers. However, as observed in this study, this communication, distribution of SCPs, and delineation of roles do not occur regularly and previous research has repeatedly found this model to be lacking in the frequency, timing, and content [8, 11, 12, 14]. Thus, there is a need for a guideline supporting oncologists and PCPs in survivorship care regarding communication and cooperation across disciplines. Another potential strategy to improve communication and clarification of roles may be educational interventions for both PCPs and oncologists. Donohue and colleagues [34] found significant improvements in knowledge of SCP existence, content, and location in the EMR from a brief 15-min educational session. Further research is warranted to determine the best methods to improve PCP-oncologist communication and care coordination for cancer survivors. This is of particular importance for older breast cancer survivors, who may need additional provider support, compared with younger breast cancer survivors, regarding their age-, cancer-, and treatment-related issues.

There are limitations worth noting in this study. The sample size may affect the generalizability of the results. However, because little is known about the receipt of SCPs and care coordination of older breast cancer survivors from the perspectives of PCPs, semi-structured interviews were chosen to facilitate greater in-depth exploration of these issues. In addition, the affiliation of these PCPs to a large academic medical center within a singular health care system may limit the generalizability of these results. Because the majority of cancer centers in the USA are operating in academic settings, these results may be generalizable to other academic medical settings [9]. In other health care systems, such as gatekeeper types of health systems, the PCP role is more well-defined and thus, possibly facilitate better communication between oncologists and PCPs [30]. Other generalizability issues are higher percentages of younger and/or female PCPs and lower patient load compared with a national PCP sample [35]. However, the study focused on older breast cancer survivors, which may produce a physician profile similar to geriatrics such as longer clinic visit duration [36] and higher percentages of younger and/or female physicians [31]. Studies on SCPs [37, 38], utilizing qualitative methodology, have had similar sample sizes. Lastly, despite the study focus on PCPs and their care of older breast cancer survivors, interviews did not highlight the challenges of the health complexities of aging and geriatric issues during cancer survivorship.

Conclusion

This study examined PCPs’ role in survivorship care of older breast cancer survivors, their knowledge, experiences, and opinions of SCPs, and suggestions for improving care coordination and facilitation of SCPs among older breast cancer survivors. Results indicated that a minority of PCPs knew of and received SCPs from oncologists regarding their patients, despite being positive about the SCP content. The PCP role in the survivorship care of their patients was general health promotion, a practice already being conducted in their clinics. PCPs felt that additional delegation of roles and better communication from oncologists would improve SCPs and survivorship care. PCPs’ should also assume an active role to enhance PCP-oncologist communication such as expressing their needs to oncologists regarding survivorship care of their mutual patients. More attention is needed to focus on the importance of PCPs, as they are an integral part of dual management for older breast cancer survivors post-treatment. Future research in PCPs’ role in survivorship care in a broad, diverse cancer survivor population is warranted.

References

Bluethmann SM, Mariotto AB, Rowland JH (2016) Anticipating the “silver tsunami”: prevalence trajectories and comorbidity burden among older cancer survivors in the United States. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention : a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive. Oncology 25(7):1029–1036

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A (2018) Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin 68(1):7–30

Faul LA, Luta G, Sheppard V, Isaacs C, Cohen HJ, Muss HB, Yung R, Clapp JD, Winer E, Hudis C, Tallarico M, Wang J, Barry WT, Mandelblatt JS (2014) Associations among survivorship care plans, experiences of survivorship care, and functioning in older breast cancer survivors: CALGB/Alliance 369901. J Cancer Surviv 8(4):627–637

Meneses K, Benz R, Azuero A, Jablonski-Jaudon R, McNees P (2015) Multimorbidity and breast cancer. Semin Oncol Nurs 31(2):163–169

Jacobsen PB, DeRosa AP, Henderson TO, Mayer DK, Moskowitz CS, Paskett ED et al Systematic review of the impact of cancer survivorship care plans on health outcomes and health care delivery. J Clin Oncol. 2018:Jco2018777482

Risendal BC, Sedjo RL, Giuliano AR, Vadaparampil S, Jacobsen PB, Kilbourn K, Barón A, Byers T (2016) Surveillance and beliefs about follow-up care among long-term breast cancer survivors: a comparison of primary care and oncology providers. J Cancer Surv 10(1):96–102

LaGrandeur W, Armin J, Howe CL, Ali-Akbarian L (2018) Survivorship care plan outcomes for primary care physicians, cancer survivors, and systems: a scoping review. J Cancer Surviv 12(3):334–347

Blanch-Hartigan D, Forsythe LP, Alfano CM, Smith T, Nekhlyudov L, Ganz PA, Rowland JH (2014) Provision and discussion of survivorship care plans among cancer survivors: results of a nationally representative survey of oncologists and primary care physicians. J Clin Oncol 32(15):1578–1585

Shalom MM, Hahn EE, Casillas J, Ganz PA (2011) Do survivorship care plans make a difference? A primary care provider perspective. J Oncol Pract 7(5):314–318

Dittus KL, Sprague BL, Pace CM, Dulko DA, Pollack LA, Hawkins NA et al (2014) Primary care provider evaluation of cancer survivorship care plans developed for patients in their practice. J Gen Pract (Los Angeles) 2(4):163

Cheung WY, Aziz N, Noone AM, Rowland JH, Potosky AL, Ayanian JZ, Virgo KS, Ganz PA, Stefanek M, Earle CC (2013) Physician preferences and attitudes regarding different models of cancer survivorship care: a comparison of primary care providers and oncologists. J Cancer Surviv 7(3):343–354

Shen MJ, Binz-Scharf M, D'Agostino T, Blakeney N, Weiss E, Michaels M, Patel S, McKee MD, Bylund CL (2015) A mixed-methods examination of communication between oncologists and primary care providers among primary care physicians in underserved communities. Cancer 121(6):908–915

Sada YH, Street RL Jr, Singh H, Shada RE, Naik AD (2011) Primary care and communication in shared cancer care: a qualitative study. Am J Manag Care 17(4):259–265

Dossett LA, Hudson JN, Morris AM, Lee MC, Roetzheim RG, Fetters MD, Quinn GP (2017) The primary care provider (PCP)-cancer specialist relationship: a systematic review and mixed-methods meta-synthesis. CA Cancer J Clin 67(2):156–169

Forsythe LP, Parry C, Alfano CM, Kent EE, Leach CR, Haggstrom DA, Ganz PA, Aziz N, Rowland JH (2013) Use of survivorship care plans in the United States: associations with survivorship care. J Natl Cancer Inst 105(20):1579–1587

Haq R, Heus L, Baker NA, Dastur D, Leung FH, Leung E, Li B, Vu K, Parsons JA (2013) Designing a multifaceted survivorship care plan to meet the information and communication needs of breast cancer patients and their family physicians: results of a qualitative pilot study. BMC Med Informatics Decis Mak 13:76

Bober SL, Recklitis CJ, Campbell EG, Park ER, Kutner JS, Najita JS, Diller L (2009) Caring for cancer survivors: a survey of primary care physicians. Cancer 115(18 Suppl):4409–4418

American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer (2012) Cancer program standards 2012: ensuring patient-centered care. Chicago, IL

American Society of Clinical Oncology (2014) Survivorship care planning tools. Available from: https://www.asco.org/practice-guidelines/cancer-care-initiatives/prevention-survivorship/survivorship-compendium. Accessed 5 Dec 2018

Office of Cancer Communications NCI (2002) Making health communication programs work : a planner’s guide. U.S. Dept. of health and human services, public health service, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda

Hewitt M, Greenfield S, Stovall E (2006) From cancer patient to cancer survivor: lost in translation. Institute of Medicine, Washington, DC

Runowicz CD, Leach CR, Henry NL, Henry KS, Mackey HT, Cowens-Alvarado RL, Cannady RS, Pratt-Chapman ML, Edge SB, Jacobs LA, Hurria A, Marks LB, LaMonte SJ, Warner E, Lyman GH, Ganz PA (2016) American cancer society/American society of clinical oncology breast cancer survivorship care guideline. J Clin Oncol 34(6):611–635

Virgo KS, Lerro CC, Klabunde CN, Earle C, Ganz PA (2013) Barriers to breast and colorectal cancer survivorship care: perceptions of primary care physicians and medical oncologists in the United States. J Clin Oncol 31(18):2322–2336

Nekhlyudov L, O’Malley DM, Hudson SV (2017) Integrating primary care providers in the care of cancer survivors: gaps in evidence and future opportunities. Lancet Oncol 18(1):e30–ee8

Hong S, Nekhlyudov L, Didwania A, Olopade O, Ganschow P (2009) Cancer survivorship care: exploring the role of the general internist. J Gen Intern Med 24(Suppl 2):S495–S500

Ezendam NP, Nicolaije KA, Kruitwagen RF, Pijnenborg JM, Vos MC, Boll D et al (2014) Survivorship care plans to inform the primary care physician: results from the ROGY care pragmatic cluster randomized controlled trial. J Cancer Surviv 8(4):595–602

Mayer DK, Nekhlyudov L, Snyder CF, Merrill JK, Wollins DS, Shulman LN (2014) American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical expert statement on cancer survivorship care planning. J Oncol Pract 10(6):345–351

Wildiers H, Heeren P, Puts M, Topinkova E, Janssen-Heijnen ML, Extermann M et al (2014) International Society of Geriatric Oncology consensus on geriatric assessment in older patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol 32(24):2595–2603

Dulko D, Pace CM, Dittus KL, Sprague BL, Pollack LA, Hawkins NA, Geller BM (2013) Barriers and facilitators to implementing cancer survivorship care plans. Oncol Nurs Forum 40(6):575–580

Greenfield G, Foley K, Majeed A (2016) Rethinking primary care’s gatekeeper role. BMJ 354:i4803

Association of American Medical Colleges (2017) Physician specialty data report

Mead H, Pratt-Chapman ML, Gianattasio K, Cleary S, Gerstein M (2017) Identifying models of cancer survivorship care. J Clin Oncol 35(5S):1–11

Oeffinger KC, McCabe MS (2006) Models for delivering survivorship care. J Clin Oncol 24(32):5117–5124

Donohue S, Haine JE, Li Z, Trowbridge ER, Kamnetz SA, Feldstein DA et al (2017) The impact of a primary care education program regarding cancer survivorship care plans: results from an engineering, primary care, and oncology collaborative for survivorship health. J Cancer Educ

White B (2012) The state of family medicine. Fam Pract Manag 19(1):20–26

Yabroff KR, Guy GP Jr, Ekwueme DU, McNeel T, Rozjabek HM, Dowling E, Li C, Virgo KS (2014) Annual patient time costs associated with medical care among cancer survivors in the United States. Med Care 52(7):594–601

Faul LA, Rivers B, Shibata D, Townsend I, Cabrera P, Quinn GP, Jacobsen PB (2012) Survivorship care planning in colorectal cancer: feedback from survivors & providers. J Psychosoc Oncol 30(2):198–216

Baravelli C, Krishnasamy M, Pezaro C, Schofield P, Lotfi-Jam K, Rogers M, Milne D, Aranda S, King D, Shaw B, Grogan S, Jefford M (2009) The views of bowel cancer survivors and health care professionals regarding survivorship care plans and post treatment follow up. J Cancer Surviv 3(2):99–108

Funding

This study was financially supported by the Clinical and Translational Science Award (UL1TR001070) from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Krok-Schoen, J.L., DeSalvo, J., Klemanski, D. et al. Primary care physicians’ perspectives of the survivorship care for older breast cancer survivors: a pilot study. Support Care Cancer 28, 645–652 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-019-04855-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-019-04855-5