Abstract

Purpose

The triple negative breast cancer (TNBC) subtype, known to be aggressive with high recurrence and mortality rates, disproportionately affects African-Americans, young women, and BRCA1 carriers. TNBC does not respond to hormonal or biologic agents, limiting treatment options. The unique characteristics of the disease and the populations disproportionately affected indicate a need to examine the responses of this group. No known studies describe the psychosocial experiences of women with TNBC. The purpose of this study is to begin to fill that gap and to explore participants’ psychosocial needs.

Method

An interpretive descriptive qualitative approach was used with in-depth interviews. A purposive sample of adult women with TNBC was recruited. Dominant themes were extracted through iterative and constant comparative analysis.

Results

Of the 22 participants, nearly half were women of color, and the majority was under the age of 60 years and within 5 years of diagnosis. The central theme was a perception of TNBC as “an addendum” to breast cancer. There were four subthemes: TNBC is Different: “Bottom line, it’s not good”; Feeling Insecure: “Flying without a net”; Decision-Making and Understanding: “A steep learning curve”; and Looking Back: “Coulda, shoulda, woulda.” Participants expressed a need for support in managing intense uncertainty with a TNBC diagnosis and in decision-making.

Conclusions

Women with all subtypes of breast cancer have typically been studied together. This is the first study on the psychosocial needs specifically of women with TNBC. The findings suggest that women with TNBC may have unique experiences and unmet psychosocial needs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

There are 3.1 million female breast cancer survivors in the USA [1], yet women who are African-American, young, and of low socioeconomic status have poorer survival rates than many other sociodemographic groups [2, 3]. These women are also more likely to be diagnosed with triple negative breast cancer (TNBC), a breast cancer subtype that lacks receptors for estrogen, progesterone, and human epidermal growth factor. TNBC is often associated with an aggressive histology and higher rates of recurrence and mortality [4]. There is an increased chance of recurrence within the first 5 years, which peaks at year 3 [5]. There is no standard treatment or targeted therapy for TNBC. In 2014, there were an estimated 231,841 new cases of invasive cancer in the USA [3] and TNBC represents 15–20 % of all new diagnoses [4]. Risk factors unique to TNBC include young age, ethnic minorities, origin of ancestry, and BRCA1 mutations [4, 6].

TNBC incidence rates among African-American women are at least twice those among non-Hispanic Whites [7], and African women have the highest prevalence. Ghanaian women have a much higher incidence rate (82 %), as compared to African-Americans (26 %) and non-Hispanic Whites (16 %) in the USA [4]. Similarly, women from Senegal and Nigeria have higher rates for TNBC than American women and frequently are diagnosed at younger ages [4]. Only 20 % of TNBC is detected by mammography as many younger women have not yet reached the recommended screening age [4].

Psychosocial responses to a breast cancer diagnosis affect recovery and quality of life [8]. Fears of recurrence, sense of increased vulnerability, changes in mood, and adjustment within social roles are common responses to a breast cancer diagnosis [9, 10]. In addition, physical treatment effects such as fatigue, sleep disturbance, pain, menopausal symptoms, and sexuality concerns can continue beyond treatment [10].

While these symptoms may represent a universal experience for women with breast cancer, compared to other groups, African-American breast cancer survivors have reported greater malaise, poorer physical and social well-being, worse physical functioning, and more frequent inability to work [11]. They also report a greater need for information, emotional care, and assistance in navigating the health care system [12]. Young breast cancer survivors have poorer psychological outcomes [13], greater fears of recurrence, more concerns about body image [14], depression, stress, and worse quality of life [15, 16]. Premature menopause and infertility resulting from chemotherapy contribute substantially to a young woman’s adjustment to breast cancer [15, 17, 18].

As there are no known studies on the experience of women with TNBC, the purpose of this study is to describe the experience of women with TNBC and explore their psychosocial needs. As younger women and African-American women are disproportionately diagnosed with TNBC, which is a unique subtype of breast cancer with no established standard treatment, the findings from this study will contribute new information on the coping and adjustment of these distinct breast cancer populations. In this era of personalized patient-centered cancer care, these data will provide insight and guidance for providers to better address specific patient population needs. As providers are better able to attend to these needs and as patients are better able to cope with a TNBC diagnosis, health outcomes may improve and quality of life may be enhanced.

Method

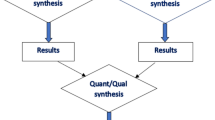

Qualitative inquiry is an appropriate methodology when the reality of a target population’s experience is unknown [19, 20]. Interpretive description is a systematic approach to analyze data that goes beyond description and seeks to identify patterns and relationships of the phenomenon [21–23]. Interpretive description is particularly useful in applied health fields because it attempts to understand common themes, as well as distinct variations within the area of interest [21–23]. Early stages of analysis focus on breadth and defining the scope of the phenomenon, and later stages move to synthesis, theorizing and reconceptualizing the data into a cohesive thematic outcome. Attention is also given to individual variation. This study was approved by a human subjects review board, and ethical guidelines were followed.

Sample

Purposive and convenience sampling techniques were used to recruit women 18 years or older, English speaking, diagnosed and treated for TNBC, with no evidence of recurrence prior to study enrollment. Participants were recruited from a metropolitan hospital, community oncology practices, local breast cancer support groups, and health care provider referrals. Of the 29 women who contacted the principal investigator, 28 met eligibility criteria and 22 consented to participate between March 2012 and April 2014.

Data collection

Participants completed a questionnaire to obtain demographic (age, race/ethnicity, marital status, children, living situation, education, employment status, and income) and medical information (weight/height, cancer location, primary therapy, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, receptor status, cancer stage, menopausal status, cancer history, family history, and comorbidities). Semi-structured interviews were conducted at a location convenient to the participant (see Fig. 1). Interviews were audio-taped, and the recordings were transcribed verbatim. The transcriptions were entered into a data management program, ATLAS.ti.

Data analysis

Three researchers coded the transcripts independently; any inconsistencies were discussed among the group until consensus was reached. In the first phase of analysis, 119 codes were identified, and the second phase of analysis generated 68 s level codes. Using constant comparative data analysis, patterns and relationships were identified. Data collection continued until saturation of the dominant themes. Additional data sources included field notes, personal reflections, and expert opinion from authorities in psychosocial oncology, qualitative research methodology, and medical oncology.

To ensure methodologic rigor, this study applied Lincoln and Guba’s criteria for trustworthiness [24]. In qualitative research, trustworthiness is a parallel to quantitative research criteria of internal validity, reliability, objectivity, and external validity. Trustworthiness includes credibility, the confidence in establishing truth of the data; transferability, the degree to which the data could be applicable to other settings or groups; dependability, which considers the context in which the research takes place; and confirmability, which reflects the accuracy and relevance of the data analysis to findings.

Results

Demographic and medical findings

The sample consisted of 22 participants with a mean age of 53 years. Nearly half were women of color (45 %), and the majority were within 5 years of diagnosis, under the age of 60 years, and had received neo-adjuvant or adjuvant chemotherapy (see Tables 1 and 2).

Thematic findings

TNBC as “an addendum” to the common breast cancer response described the dominant experience of the participants. Four subthemes explained this perspective: TNBC is Different “Bottom line, it’s not good”; Feeling Insecure: “Flying without a net”; Decision-Making and Understanding: “A steep learning curve”; and Looking Back: “Coulda, shoulda, woulda” (see Fig. 2).

TNBC as “an addendum.” The central theme describes the experience of women with TNBC as different than what they knew about women with estrogen-positive breast cancer.

“I have a sense that [the TNBC experience] diverged a lot in the beginning because it was confusing…trying to understand what to do. And then once you start into treatment, I think you feel like you’re all in the same boat again with everybody. And now, sort of afterwards, there’s slight differences.”

One participant described this divergence: “… the triple negative is like an addendum to having [breast] cancer.”

TNBC is Different “Bottom line, it’s not good.” Participants learned about TNBC over time and understood that it often has an aggressive histology with higher recurrence and mortality rates and limited treatment options. Women concluded that it was the least desirable of the breast cancer subtypes. “That’s the bad kind… the dangerous kind” “I knew this was the worst kind I could get.” Women focused on recurrence rates and believed that if they could get beyond year 5, they would be less anxious. “If I can get past year three with nothing, then I’ll start to relax a little bit.” However, many others continued to list fear of recurrence as one of their “biggest concerns,” even those beyond 5 years. The lack of treatments targeted to TNBC compounded many of the women’s fears. While some were relieved to not undergo additional treatment, such as anti-estrogen therapy, others expressed intense worry because they did not have an additional option to reduce their chance of recurrence.

Knowledge of TNBC evoked powerful emotions. Women described experiencing “terror” and some required medication or professional support to manage their anxiety. Not only was it a struggle for women to assimilate information about TNBC and manage their emotions, but many found a lack of support from their network of family and friends due to limited understanding about TNBC. “People kind of look at you with three heads when you tell them you have breast cancer, but it’s a different kind.” Because of common beliefs in society that breast cancer is highly curable, many women with TNBC felt that their concerns about TNBC were unaddressed or minimized. “People don’t understand what you’re going through…They’ll think, ‘Okay, you know breast cancer today is really curable and…it’s scary, but,- ’…But, for triple negative, it’s not so curable and so they don’t understand your fears…” Participants found it confusing to discern which recommendations pertained to TNBC versus an estrogen-positive cancer when well-meaning people gave advice or participants came across information on breast cancer (e.g., the dietary recommendation to avoid soy, which potentially affects estrogen levels).

Feeling Insecure: “Flying without a net.” This theme captures a heightened degree of uncertainty that accompanies a TNBC diagnosis. “I began to realize there’s more to the triple negativity than just saying… you don’t take tamoxifen or Herceptin®, because it won’t do you any good. It’s really flying without a net.” Women’s insecurity was especially intensified with the knowledge that options such as anti-estrogen or targeted therapy were not available to them, particularly when transitioning from active treatment to survivorship. “I think it’s harder for triple negatives, because estrogen positive people, when they leave their last treatment and they walk out with their script with tamoxifen, they feel like they have something to grip, to hold onto.” Women related that the uncertainty was always in the back of their minds and persisted well into survivorship. The knowledge of limited treatment options was often accompanied by a sense of powerlessness and lack of control. “I really kinda feel adrift…given that I can’t take those drugs to give me that sense of security.”

Women would have liked more attention from their providers or acknowledgement of their fears. “It’s the uncertainty and the always low level anxiety because of the fact that it’s triple negative…And, that’s something no one has addressed…Somebody needs to address that legitimate fear.” Participants wanted protocols specific to TNBC rather than being “clumped” together with all breast cancer patients. “It would be nice, …once you…get the pathology back that you’re triple negative, then you’re channeled to a triple negative field, rather than being in the whole universe here.” Women believed that more frequent contact with a provider and monitoring would result in early detection of recurrence, provide reassurance, and help manage their fears.

Decision-Making and Understanding: “A steep learning curve.” Decision-making was challenging for women with TNBC because of the volume of information to be processed and the “steep learning curve.” “It’s so much information coming at you so intensely.” Women found that their emotional responses and distress challenged their ability to process information. “I didn’t know anything about triple negative. And, I think at that point I was so devastated, you know, after hearing the news, that I really didn’t even ask questions.” Many of the participants reported that they did not fully understand the implications of the diagnosis and consequences of the treatment options presented.

“I didn’t really truly understand everything what they were telling me. I didn’t know what triple negative meant. I didn’t know what- well actually they didn’t use those words. They just said, … the estrogen is negative, this is negative, that’s negative. But, I didn’t know what that meant.”

The pace at which the information came varied for women. Some women were overwhelmed with how quickly the information came, and others felt the information came too slowly. In addition to information from their providers, women turned to other sources with mixed results. Information from the Internet, friends, support groups, and second and third opinions either helped clarify women’s understanding or led to further questions and uncertainty.

Most women came to a greater understanding of their diagnosis during or after treatment. They did not fully comprehend TNBC when they were making treatment decisions. “I didn’t fully grasp the whole triple negative until I was actually in the midst of taking chemo and then going to the support group. And, the reason being is because there is so much information.” Some women wished that they had more clear information initially, while others preferred receiving information over time so that they could manage their emotional responses. Even after treatment, several women commented that they did not satisfactorily understand the diagnosis, which affected their ability to feel comfortable in survivorship. “To be honest with you, I still don’t have a clear understanding of it.” “There’s still some pieces to [TNBC] that I don’t completely understand.” “I don’t know enough information to go out and to say to someone, ‘I have triple negative and blah, blah, blah.’ I just- I don’t have enough information.” Almost all women expressed a need to be kept informed of new research findings going forward.

Understanding the number and types of treatment options challenged the decision-making process. “There’s like a million choices they could give you, the platins…and all these different chemos that you might also want to try.” “It was confusing to try to figure out…and trying to understand what to do.” Women described feeling a sense of urgency in making treatment decisions quickly believing that their tumor was fast growing. “I was very confused and it was very scary and the idea of- of this very aggressive cancer growing in my body every minute that I delayed was very scary.” Women listed a variety factors and reasons which influenced their treatment decision: aggressiveness of TNBC, doctor’s recommendation, fear, sequencing of treatment, intuition, follow-up schedule, body image, and witnessing loved ones’ experiences with cancer treatment. Sorting through the number of treatment choices and the perceived compressed time to make decisions resulted in a stressed decision-making process.

Looking Back: “Coulda, shoulda, woulda.” Upon reflection, many women felt that the information they had and their understanding of TNBC was inadequate to make the best treatment decision. Some doubted their choice. “It’s hard to say, ‘coulda, shoulda, woulda,’ but I might have gone-, opted for the bilateral mastectomy had I truly analyzed it fully…So, I know that’s ambivalent sounding, but I’m afraid that’s the way it is.” Several women expressed regret and wished they had made a different decision. “I regret not having had the mastectomy.” “My only regret was that I didn’t pursue having a double mastectomy. And, I should have been a lot more persistent in just having it done.”

The ambivalence and uncertainty lingered beyond the end of treatment. “In the back of my mind, I’m still like, ‘Did I do the right thing?’ But, you know, you don’t know. You don’t know.” Persistent apprehension caused some women to believe that, if they had a recurrence, it would be because they made the wrong treatment decision. Of the women who had decisional regret, most believed that the better option would have been to have had more invasive or aggressive treatment than what they chose. Women believed that they would have had greater peace of mind.

Discussion

The findings of this study suggest that a diagnosis of TNBC adds a layer of complexity to the breast cancer experience. The majority of women diagnosed with breast cancer report information to be overwhelming and that decision-making is often compressed, but the uniqueness of the biologic and prognostic features and limited treatment options for TNBC significantly contributes to increased stress. Cancer patients with high stress levels at diagnosis are reported to have greater needs for information and decision support [25]. Women in the current study believed that their uncertainty and stress were particularly intense because of their perceptions that TNBC is an aggressive breast cancer with high recurrence rates. The level of ambiguity about their illness is related to the amount of information, the disease complexity, and perceived unpredictability of the disease [26].

As described in the subtheme, Feeling Insecure: “Flying without a net,” limited information and understanding, in addition to having a disease with poor prognosis, directly contributed to uncertainty. Uncertainty is related to poorer psychological adjustment and physical health [27]. Young women with cancer are more likely than older women to experience uncertainty and are particularly vulnerable to psychosocial distress [28]. Many women are not prepared to deal with their uncertainty and do not have the resources to manage their distress [26]. Transitioning from active cancer treatment to survivorship can be a time of increased uncertainty for the majority of women with breast cancer [29] and was especially pronounced in this study of women with TNBC who were not candidates for anti-estrogen therapy. Another facet of uncertainty during the transition to survivorship phase is learning to navigate the persistent side effects of treatment and fears of recurrence [30]. Uncertainty during this phase of the cancer trajectory can affect long-term adjustment, and psychosocial support to manage fear of recurrence and emotional distress is indicated [26, 31].

Many of the participants in this study questioned their decisions, and some even expressed regret. Anxiety over a diagnosis, along with a sense of urgency, can lead to decisional regret [32]. Decision satisfaction is associated with a patient’s preferences and values [33]. None of the women in this study reported being asked about their preferences and values in the decision-making process. Providing time and support for women to clarify their values while contemplating various treatment options has been suggested as a way to facilitate decision-making [34]. Shared decision-making contributes to increased levels of patient satisfaction [33, 35]. In contrast, assuming a passive role in the decion making process results in higher levels of distress and lower quality of life [36, 37]. Sociodemographic factors are known to influence the decision-making process and contribute to decisional regret. Racial and ethnic populations, such as African-Americans, may have specific information and support needs [38]. Younger women who live alone and who are highly educated are more likely to experience distress over their decisions [33].

Even though decisional conflict may be present in patients with other breast cancer subtypes, in TNBC, it may be related to the urgency women feel to make decisions because of the aggressiveness of TNBC and the woman’s incomplete information about the disease at the time of choosing treatment. The most common regret that participants expressed was related to the participant’s surgical choice. These women perceived mastectomy as a better option than breast conserving surgery. Even when presented with evidence on the equivalent survival outcomes [39], many participants stated that a mastectomy or bilateral mastectomies would have alleviated some of their anxiety about recurrence.

Although this study has relevant findings, there are some limitations. A purposive sampling technique generated a sample with higher income and educational levels than the target population. For that reason, it may not fully reflect the populations who are commonly diagnosed with TNBC. Self-selection bias may have also contributed to the non-representative sample. Only English-speaking women were eligible to participate in the study; thus, the experience of non-English speaking women was not represented.

Conclusions

This study addressed a gap in the literature on the experience of women diagnosed and treated for TNBC, and the findings have implications for research and practice. Future research should explore patient informational needs around the amount, sources, and pace of the information received, as well as help with understanding and managing emotional responses. Research could also explore ways of supporting women with TNBC cope with uncertainty around attributes of the disease, such as its aggressiveness and limitations in treatment. It would be useful to know if women with TNBC would benefit from the use of a decision aid and support. Decision aids have been found to be useful in helping cancer patients make treatment decisions and increase decision satisfaction [39, 40]. Patient decision satisfaction was also related to help with clarifying personal values and feeling supported in decision-making [34].

Clinically, health care practitioners may benefit from knowing that patients with TNBC may be more likely to experience heightened fear and insecurity. Future research might assist health care providers to assess the level of involvement an individual would like in their treatment choices [35]. Women who believe their cancer is aggressive may value anticipatory guidance from their providers and resources for information and support. It is also important for providers to monitor their patients’ levels of distress during treatment and beyond and to make referrals, if needed. Many of the women in this study believed that TNBC differed significantly enough from other breast cancer subtypes to warrant distinct treatment and follow-up guidelines. As the science of TNBC builds, researchers and practitioners should consider the appropriateness of separate clinical guidelines for TNBC.

References

DeSantis CE, Lin CC, Mariotto AB, Siegel RL, Stein KD, Kramer JL et al (2014) Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin 64(4):252–271

American Cancer Society (2014). Breast cancer: Detailed guide. http://www.cancer.org/cancer/breastcancer/detailedguide/breast-cancer-key-statistics. Accessed 24 March 2014

Siegel R, Ma J, Zou Z, Jemal A (2014) Cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin 64(1):9–29

Turkman YE, Sakibia Opong A, Harris LN, Knobf MT (2015) Biologic, demographic, and social factors affecting triple negative breast cancer outcomes. Clin J Oncol Nurs 19(1):62–67

Fornier M, Fumoleau P (2012) The paradox of triple negative breast cancer: novel approaches to treatment. Breast J 18(1):41–51

Brouckaert O, Wildiers H, Floris G, Neven P (2012) Update on triple-negative breast cancer: prognosis and management strategies. Int J Womens Health 4:511–520

Wright JL, Reis IM, Zhao W, Panoff JE, Takita C, Sujoy V et al (2012) Racial disparity in estrogen receptor positive breast cancer patients receiving trimodality therapy. Breast 21(3):276–283

Knobf MT (2011) Clinical update: psychosocial responses in breast cancer survivors. Semin Oncol Nurs 27(3):e1–e14

Reyes-Gibby CC, Anderson KO, Morrow PK, Shete S, Hassan S (2012) Depressive symptoms and health-related quality of life in breast cancer survivors. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 21(3):311–318

Harrington CB, Hansen JA, Moskowitz M, Todd BL, Feuerstein M (2010) It’s not over when it’s over: long-term symptoms in cancer survivors--a systematic review. Int J Psychiatry Med 40(2):163–181

Rao D, Debb S, Blitz D, Choi SW, Cella D (2008) Racial/ethnic differences in the health-related quality of life of cancer patients. J Pain Symptom Manage 36(5):488–496

Ashing-Giwa K, Lim JW (2011) Examining emotional outcomes among a multiethnic cohort of breast cancer survivors. Oncol Nurs Forum 38(3):279–288

Adams E, McCann L, Armes J, Richardson A, Stark D, Watson E et al (2011) The experiences, needs and concerns of younger women with breast cancer: a meta-ethnography. Psychooncology 20(8):851–861

Ruddy KJ, Partridge AH (2012) Treatment of breast cancer in young women. Clin Pract 9(2):171–180

Howard-Anderson J, Ganz PA, Bower JE, Stanton AL (2012) Quality of life, fertility concerns, and behavioral health outcomes in younger breast cancer survivors: a systematic review. J Natl Cancer Inst 104(5):386–405

Janz NK, Hawley ST, Mujahid MS, Griggs JJ, Alderman A, Hamilton AS et al (2011) Correlates of worry about recurrence in a multiethnic population-based sample of women with breast cancer. Cancer 117(9):1827–1836

Canada AL, Schover LR (2012) The psychosocial impact of interrupted childbearing in long-term female cancer survivors. Psychooncology 21(2):134–143

Gabriel CA, Domchek SM (2010) Breast cancer in young women. Breast Cancer Res 12(5):212

Polit DF, Beck CT (2012) Nursing research: generating and assessing evidence for nursing practice, 9th edn. Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia

Creswell JW (2007) Qualitative inquiry and research design: choosing among five approaches, 2nd edn. Sage Publications, Inc, Thousand Oaks

Thorne S, Kirkham SR, MacDonald-Emes J (1997) Interpretive description: a noncategorical qualitative alternative for developing nursing knowledge. Res Nurs Health 20(2):169–177

Thorne S, Kirkham SR, O’Flynn-Magee K (2004) The analytic challenge in interpretive description. Int J Qual Methods 3(1):1–11

Thorne S (2008) Interpretive description. Left Coast Press, Inc, Walnut Creek

Lincoln YS, Guba EG (1985) Naturalistic inquiry. Sage, Hollywood

Czaja R, Manfredi C, Pierce J (2003) The determinants and consequences of information seeking among cancer patients. J Health Commun 8:529–562

Germino BB, Mishel MH, Crandell J, Porter L, Blyler D, Jenerette C et al (2013) Outcomes of an uncertainty management intervention in younger African American and Caucasian breast cancer survivors. Oncol Nurs Forum 40(1):82–92

Hall DL, Mishel MH, Germino BB (2014) Living with cancer-related uncertainty: associations with fatigue, insomnia, and affect in younger breast cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer 22(9):2489–95

Sammarco A (2009) Quality of life of breast cancer survivors: a comparative study of age cohorts. Cancer Nurs 32(5):347–56

Garofalo JP, Choppala S, Hamann HA, Gjerde J (2009) Uncertainty during the transition from cancer patient to survivor. Cancer Nurs 32(4):E8–E14

Mollica M, Nemeth L, Newman SD, Mueller M (2014) Quality of life in African American breast cancer survivors: an integrative literature review. Cancer Nurs 38(3):194–204

Buzaglo JS, Miller SM, Kendall J, Stanton AL, Wen KY, Scarpato J et al (2013) Evaluation of the efficacy and usability of NCI’s Facing Forward booklet in the cancer community setting. J Cancer Surviv 7(1):63–73

Spittler CA, Pallikathayil L, Bott M (2012) Exploration of how women make treatment decisions after a breast cancer diagnosis. Oncol Nurs Forum 39(5):E425–33

Budden LM, Hayes BA, Buettner PG (2014) Women’s decision satisfaction and psychological distress following early breast cancer treatment: a treatment decision support role for nurses. Int J Nurs Pract 20(1):8–16

Kokufu H (2012) Conflict accompanying the choice of initial treatment in breast cancer patients. Jpn J Nurs Sci 9(2):177–184

Taylor A, Tischkowitz M (2014) Informed decision-making is the key in women at high risk of breast cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol 40(6):667–669

Hack TF, Carlson L, Butler L, Degner LF, Jakulj F, Pickles T et al (2011) Facilitating the implementation of empirically valid interventions in psychosocial oncology and supportive care. Support Care Cancer 19(8):1097–1105

Seror V, Cortaredona S, Bouhnik AD, Meresse M, Cluze C, Viens P et al (2013) Young breast cancer patients’ involvement in treatment decisions: the major role played by decision-making about surgery. Psychooncology 22(11):2546–2556

Matthews AK, Tejeda S, Johnson TP, Berbaum ML, Manfredi C (2012) Correlates of quality of life among African American and white cancer survivors. Cancer Nurs 35(5):355–364

Lam WW, Chan M, Or A, Kwong A, Suen D, Fielding R (2013) Reducing treatment decision conflict difficulties in breast cancer surgery: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 31(23):2879–2885

Stacey D, Legare F, Col NF, Bennett CL, Barry MJ, Eden KB et al (2014) Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 1:CD001431

Acknowledgments

This study was funded in part by the Susan G. Komen Foundation Training in Disparities Research Grant and American Cancer Society Doctoral Degree Scholarship in Cancer Nursing, DSCN-12-203-01-SCN. The authors gratefully acknowledge the editorial comments of Elayne K. Phillips, PhD, RN, FAAN.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Turkman, Y.E., Kennedy, H.P., Harris, L.N. et al. “An addendum to breast cancer”: the triple negative experience. Support Care Cancer 24, 3715–3721 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-016-3184-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-016-3184-4