Abstract

Purpose

The aims of the study were (1) to understand the relationship between women’s marital coping efforts and body image as well as sexual relationships and (2) to test a hypothesized model suggesting that marital coping efforts have a mediating effect on the relationship between body image and sexual relationships among breast cancer survivors.

Methods

A total of 135 breast cancer survivors who had finished cancer treatment completed a self-reported questionnaire concerning body image, marital coping efforts, and sexual relationship.

Results

Body image, marital coping, and sexual relationship were found to be significantly correlated with each other. The final path model showed that negative marital coping efforts, including avoidance and self-blame, significantly mediated the effect of women’s body image on their sexual relationships. Although a positive approach did not correlate with body image, it did significantly correlate with women’s sexual relationships.

Conclusions

Our study demonstrated that negative marital coping using self-blame and avoidance mediated the association between body image and sexual relationship. Future interventions to address the body image and sexual life of breast cancer survivors should be considered using positive approaches that prevent disengaged avoidance or self-blame coping efforts intended to deal with marital stress.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most commonly occurring malignancy in women. According to the estimated statistics from the World Health Organization in 2012, approximately 1.67 million women worldwide were newly diagnosed with breast cancer [1]. Advances in breast cancer treatments have increased the rates of survival, with over 90% of women surviving for 5 years post diagnosis [2]. This has led us to place a greater emphasis on their quality of life, especially on their sexual relationships with their partners [3]. Sexuality and intimacy are important survivorship concerns for breast cancer patients [4]. Changes in sexuality may impact women’s quality of life [5]. Women with breast cancer face the impact of body image changes after surgery, and their sexual life is also influenced by the subsequent chemotherapy and continued hormone therapy [6]. Studies have revealed that women treated for breast cancer with surgery, chemotherapy, and hormone therapy experience disturbances in body image and sexual well-being that extend well beyond the acute phase of treatment [7, 8].

Body image has been validated to be associated with women’s sexuality [9, 10]. Although treatment factors have been considered to be the original contributors to women’s sexual problems, several studies have demonstrated that cancer treatment has limited effects on women’s sexual well-being when considering women’s body image as a factor for analysis [6, 10, 11]. Sexuality in the context of a cancer experience not only refers to sexual function but also to the psychological aspects of a person [12]. Thus, when examining women’s sexual well-being as part of an integrated physical and psychological perspective, body image should be viewed an important cause of sexual problems among women with breast cancer.

Breast cancer is regarded as a “couple’s” disease, and it has been posited to increase marital strain. The diagnosis of breast cancer and related treatments may change women’s usual roles, where some roles may be replaced by the husband [13]. Previous studies have demonstrated that husbands of women with breast cancer report similar levels of stress to those of their wives when trying to carry out their usual roles at home and work [14]. These role changes may come to place stress on women’s relationships with their partners and may in turn result in marital strain. Constructive coping, such as mutually dealing with marital strain, will help couples experience more positive adjustment following breast cancer treatment [15]. However, if couples avoid facing the associated problems or, conversely, are overly responsive and nervous in order to lessen the intrusion resulting from the cancer, they will usually have difficulties with recovery [16, 17].

Body image has been identified as a perception of self that reflects the picture of the body in a person’s mind. Definitions of feminine beauty in the current society also influence how women evaluate their bodies [18]. Thus, women are concerned with how they appear to others, especially how they appear to their partners. Because their breasts symbolize femininity, these concerns are exacerbated among women who have experienced breast mutilation [19, 20]. As a result, body image changes may also be regarded as a stress introduced after breast cancer treatment [21]. The use of avoidance coping strategies, which give women short-term relief through escape, can minimize the discomfort associated with a change in body image. Because interactions exist between individual coping and mutual support processes among couples [15], using negative coping strategies that distance them from their intimate partners can discourage partner support. This will then contribute to marital strain and influence their management of that strain. As a result, a greater degree of negative body image could possibly foster the negative coping strategies that women use to reduce marital strain.

Given the fact that women’s sexuality may be affected by body image [9, 10] and that changes in body image can strengthen negative coping strategies related to marital strain, this effect could in turn impact women’s sexual relationships with their partners. Breast cancer affects both partners in a relationship and is considered to be a dyadic stressor. Seeing such stress as shared stress at the couple level may help us to understand stress communication patterns and methods for dealing with marital strain as both team and individual work [22]. It would be helpful for us to understand more elements of this complex issue when developing couple-based intervention. Thus, we hypothesize that women’s body image problems may predict negative rather than positive coping efforts directed at dealing with marital strain, which may then determine their sexual relationships. The objectives of this study were (1) to understand the relationship between women’s marital coping efforts and body image as well as sexual relationship and (2) to test a path model wherein the relationship between body image and sexual relationship is used to mediate different types of coping effort.

Methods

Participants

Women were eligible to participate in this study if they met the following criteria: (1) being diagnosed with breast cancer and without metastasis, (2) completing breast cancer surgery and adjuvant therapy as necessary for at least 6 months but no more than 2 years, (3) being free from psychiatric disorders before breast cancer diagnosis, (4) being married, (5) older than 20 years, and (6) speaking Mandarin or Taiwanese. In total, 233 women were eligible for the study during the data collection period. However, 97 women did not participate because of a lack of time or because they declined to do so without providing a reason. We also excluded 1 woman who did not fill out the questions completely; ultimately, 135 women were analyzed in this study.

Procedure

Ethical consideration approval was obtained from the institutional review board (IRB) of a teaching hospital in southern Taiwan. Participants were first screened at a regular follow-up and then were asked about their willingness to participate in this study. Willing participants were approached in their outpatient clinics. A self-administered questionnaire was given after they signed the informed consent. The researcher read and explained the questions to any participant who was unable to see or to fill out the questionnaire on their own.

Measures

Demographic and treatment-related characteristics

Participants’ demographics and medical data were assessed or recorded from the patients’ medical charts, including age, year of marriage, education level, stage of cancer, treatment type, and pathology.

Body image scale (BIS)

The body image scale (BIS) is designed to capture body image discomfort in cancer survivors. The participants were asked ten items that rated their frequency of perceiving their appearance over the previous week using a scale ranging from “very often” to “never.” Higher BIS scores indicate greater levels of body image discomfort.

The BIS demonstrated high reliability and good clinical validity in a previous study. The Chinese version of the BIS has also been validated [23]. The Cronbach’s α for the BIS in this study was 0.93. Women’s beliefs about their attractiveness to their partners following cancer surgery have been shown to predict women’s satisfaction with their appearance [24, 25]. We added one more question using a visual analogue scale to measure women’s perceptions about their partner’s satisfaction with their appearance. The numbers “0” meant “not completely satisfied” and “10” meant “highly satisfied.”

Marital coping efforts (MCEs)

Marital coping as measured in this study was evaluated from the women’s perspective primarily. Women’s coping efforts related to managing marital strain were measured using the marital coping inventory developed by Bowman [26]. This scale measures five types of coping styles which concern how couples deal with recurrent marital strain in their daily lives. Five types of coping efforts were identified. The conflict subscale (15 items) reflected the use of criticism as a derisive way to resolve marital strain. The self-blame subscale (15 items) reflected distressed feelings as well as difficulties in sleeping and feeling bad about health. The positive approach subscale with 14 items reflected behaving with closeness and initiating mutual activities and good memories. The self-interest subscale (9 items) reflected deliberate increases in solitary activities. The avoidance subscale had 11 items reflecting rejection, withdrawal, and suppression of feelings. The participants were asked 64 items that rated the frequency of adoption ranging from “very often” to “never” related to dealing with their recurrent marital strain. The Chinese version of the marital coping efforts (MCEs) was validated in a previous study [27]. With the exception of the avoidance subscale, the Cronbach’s α for the MCEs in this study was between 0.78 and 0.88. The reliability of the avoidance subscale was 0.52.

Sexual relationship

Efforts to understand sexuality in the context of cancer experiences need to be more flexible in regard to seeing sexuality as focused not only on sexual function but also on intimacy and the closeness needs of couples [12]. The relationship and sexuality scale (RSS) (19 questions) was designed for women with breast cancer by Berglund [28]. This scale was intended to assess the relationships and intimacy levels of women with their partners over the previous 2 weeks. To order the questions, 0–3 or 0–4 point scores were adopted in which higher scores meant more impact on the sexual relationship. After excluding the non-ordering question and two questions not answered by most participants, three factors were identified, including sexual function, sexual frequency, and sexual fear. The overall reliability for α was 0.89. The scale has been translated into a Chinese version. The validity was also ascertained using factor analysis. The overall reliability of the Cronbach’s α was 0.85.

We reexamined the validity of the scale using factor analysis because two questions excluded by the original author could be answered by most of the participants in our study. Four factors were identified, including sexual difficulties that reflected the influence of treatments on changes in a participants’ sexual interest; sexual performance, which reflected the idea that treatments influence the quality of sex life; sexual esteem, which reflected the influence of treatments on confidence in the participants’ sex life; and sexual intimacy, which reflected the influence of treatment on their intimate interaction with their partners. The Cronbach’s α values for each factor were 0.84, 0.74, 0.54, and 0.65, respectively. The overall reliability for α was 0.85. The four factors explain 63% of the variance. Because previous sexual relationships could influence a person’s current sexual relationship [29], we added one more question using a visual analogue scale in order to understand women’s evaluations of their sexual satisfaction both before and after diagnosis.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS for Windows, version 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The normality of the outcome variable was first examined by means of skewness statistics and normal probability plots, which revealed normal distribution.

A Pearson correlation, chi-squared tests, and an analysis of variance were used to examine the relationship between demographic data, treatment characteristics and sexual relationship, body image, and marital coping efforts. This procedure was conducted to identify which factors could be predictors of sexual relationship. Those characteristics with p < .05 with total score of RSS were chosen as candidate-dependent variables for path analyses.

Finally, we used path analysis to examine the causal relationship between body image, different types of marital coping effort, and sexual relationship. Demographic and treatment characteristics with p < .05 in the correlation were used to build up an initial mediation model. The initial model was then modified by subsequently adding plausible paths with the use of modification indices to obtain the final model with good model fit.

The path analyses were performed using AMOS. We determined the appropriateness of the model according to Kline’s criteria (2011): the comparative fit index (CFI), the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) [30]. Hu and Bentler (1999) suggested that a good fit to the data will be characterized by values above .95 for the CFI, lower than .08 for the SRMR, and lower than .06 for the RMSEA. An acceptable fit to the data is defined by a CFI value of .90–.94, a SRMR value of .09–.10, and a RMSEA value of .07–.10[31].

Because of the limited samples in the path analysis, we also used bootstrapping, which is a resampling method used for approximating the sampling distribution of a statistic to validate the results.

Results

Demographic and treatment characteristics

The mean age of the participants was 53 years, ranging from 30 to 80 years. Approximately half (52.6%) of the participants reported having a high school education. About 25% of the participants were employed outside of the home. Over half of participants had undergone a mastectomy. Approximately 53% of the participants were diagnosed as having breast cancer stages 2 and 3. Sixty-five percent of the participants were treated with chemotherapy combined with hormone therapy. Among the 105 women who used hormone therapy, 47% of them were prescribed tamoxifen (Table 1).

Relationship between demographic, treatment characteristics, body image, and sexual relationship

Table 2 shows age to be positively correlated with sexual relationship, meaning that the older the women were, the more sexual relationship problems they experienced. Satisfaction with their sexual life before the diagnosis was negatively correlated with sexual relationship, meaning that women who were less satisfied with their sexual life before diagnosis reported greater distress with their sexual relationship.

Relationship between body image, marital coping efforts, and sexual relationship

As can be seen from Table 3, the correlation between body image and sexual relationship was positive (r = .43), meaning that women with poorer body image reported more sexual relationship problems. Additionally, except for self-interest coping efforts, negative coping responses to marital strain were significantly associated with women’s sexual relationship. The correlation coefficient was near the median for avoidance coping (.46) and was relatively lower for conflict coping (.23) and self-blame (.33). These findings suggest that the more negative coping efforts exerted by women, the more sexual relationship problems they reported. A positive approach coping style was negatively correlated with sexual relationship, which suggested that when more positive responses were used to deal with marital strain, there were fewer sexual relationship problems reported.

Except for self-interest coping efforts, negative coping responses to marital strain were found to be significantly associated with women’s body image. The median correlation coefficient for the self-blame type of coping with body image was .39, and it was relatively lower for conflict coping and avoidance coping with body image (.19 and .24, respectively). Additionally, women’s perception about partner’s satisfaction with their appearance was found to be significantly correlated with body image but was not correlated with any type of marital coping effort.

The mediating role of marital coping efforts in the relationship between body image and sexual relationship

Since only age and satisfaction with the sexual life before disease onset (as shown in Table 2) had p values <.05, these two variables were used to construct an initial path model. As a result of the fact that some women did not complete all of the questions in the RSS, only 89 women were examined in this analysis. In order to understand the differences in sexual relationship between women who were entered into the path analyses and those who were not, satisfaction with sexual life after diagnosis was examined. The difference examined using a t test revealed that whether women were entered or not into the path analyses did not result in significant differences in terms of their sexual satisfaction.

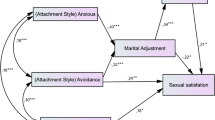

The path model for conflict is shown in Fig. 1. It can be seen that the χ 2 of the final model is 5.9, with df = 5, and p = .314. The insignificance of the chi-square test and goodness-of-fit indices (RMSEA = 0.046, SRMR = 0.07, CFI = 0.98) indicates that the final model is a good fit to the data. However, the direct effect of conflict on sexual relationship indicated that conflict coping efforts did not mediate the relationship between body image and sexual relationship.

A bootstrap analysis of the full mediation model (Fig. 1) was conducted, and the indirect effect of body image on sexual relationship through the mediating role of conflict was not significant (B = 0.064, 95% bias corrected CI [−.006, .219], β = .049, p = .076), indicating that conflict did not mediate the relation between body image and sexual relationship.

The path models for avoidance and self-blame are shown in Figs. 2 and 3. It can be seen that each of the χ 2 of the two final models is not significant (χ 2=9.2, with df = 6, and p = .162 for avoidance; χ 2 = 8.9, with df = 6, and p = .179 for self-blame). The nonsignificance of the chi-square test and goodness-of-fit indices (RMSEA = 0.078, SRMR = 0.09, CFI = 0.94 for avoidance; RMSEA = 0.074, SRMR = 0.069, CFI = 0.95 for self-blame) indicates that the final model is an acceptable fit to the data.

A bootstrap analysis of the full mediation model was then conducted to test the significance of the indirect or mediated relation between the variables. The indirect effect of body image on sexual relationship through the mediating role of avoidance and self-blame was statistically significant (B = 0.119, 95% bias corrected CI [.047, .246], β = .093, p = .021 for avoidance; B = 0.133, 95% bias corrected CI [.036, .319], β = .101, p = .005 for self-blame), indicating that both types of coping mediated the positive relation between body image and sexual relationship.

Discussion

This study addressed the significance of different types of marital coping efforts on the relationship between body image and sexual relationship. The results support the hypothesis that women with poorer body image use more negative marital coping strategies, specifically avoidance and self-blame, which in turn may lead to a poor sexual relationship.

Negative marital coping efforts as a mediator between body image and sexual relationship

The findings of this study indicate that some types of negative marital coping behavior may be a mediator between body image and sexual relationship. Previous studies have found a body image problem to be associated with one partner’s difficulty in understanding the feelings of the other [6]. Women’s perception of their partners’ difficulty with understanding their situation may cause them to decline engagement with their partners. This could be the reason why women use avoidance and self-blame to cope with their marital strain. Previous studies have found that using negative dyadic coping, such as withdrawal or avoidance of each other, resulted in poorer dyadic adjustment [22]. This finding is also consistent with our finding suggesting that avoidance and self-blame coping ultimately contribute to women’s poor sexual relationships.

The results revealed that conflict marital coping was not a mediator between body image and sexual relationship. Body image problems can lead women to engage in more conflict marital coping behavior, but this type of conflict coping will not result in a poor sexual relationship. This finding was unexpected and may be due to the culture factor. In the Chinese culture, the family is the center of a woman’s life. Chinese women keep their thoughts and feelings to themselves to decrease the impact of breast cancer on their family [32]. Women in Asian cultures are also expected to be self-sacrificing [33]. As a result, Chinese women may seldom use conflict as a method by which to resolve their marital strain. In our analysis, we found quite a few high scores on conflict coping as compared to other types of marital coping efforts. This result could be reflected in this culturally related issue. Previous studies have found that higher conflict is related to lower levels of mood disturbance and have also suggested that this may be due to the fact that when facing different opinions, confronting them directly rather than withdrawing will still benefit a couple’s relationship [15]. As a result, women’s body image problems may increase their conflicts related to marital strain. However, these may not decrease the quality of their sexual relationship. Marital coping using conflict still involves engagement between couples. This finding addresses the idea that alleviating women’s sexual relationship problems may be better achieved by focusing on dyadic coping rather than on individual coping. Marital coping as measured in this study is similar to measuring whether women regard their marriage as a unit consisting of a couple, as is the case with dyad coping. This finding was consistent with that of a previous study [34].

Positive approach marital coping and sexual relationship

The results revealed that positive approach marital coping is not correlated with body image but is correlated with sexual relationship. Body image problems therefore cannot lead women to engage in more positive approach marital coping efforts, but positive approach marital coping may influence women’s sexual relationships. It is reasonable that women with more body image problems will not initiate shared activities and good memories. However, women who deliver signals with intimacy and recall good memories with their partners will improve their sexual relationship.

Couple-based CanCOPE intervention conducted by Scott et al. (2004) revealed strong effects on women’s sense of intimacy and on self-appraisals. This CanCOPE intervention also improved women’s perceptions of their attractiveness to their partners; however, it did not affect women’s self-acceptance of their body image [24]. The author suggested that this CanCOPE intervention ignored women’s personal journeys to come to terms with the body image changes they were experiencing [35]. The results of this study underscore the idea that women’s body image should be considered when implementing couple-based intervention for their sexual relationships because this body image factor may complicate women’s coping efforts related to dealing with marital strain. As a result, interventions intended to improve the sexual relationships of women suffering from breast cancer need to be conducted in combination with both individual and dyadic sections. Individual sections could initially be focused on women’s body image issues, followed by a dyadic section that could be targeted on the coping styles between couples.

Limitations

The causal relationship was only speculative rather than confirmed because of its cross-sectional, correlational design. The sample size of this study seemed to be small, especially in the case of the structural equation modeling (SEM) analyses. Researchers [30] have suggested that a minimum of 200 samples is needed for adopting a SEM analysis, and our sample size of 89 seemed to be weak. However, we justify that our results may not be seriously biased because of the following reasons: (1) The need of a large sample size in SEM is mainly due to the latent factor. The latent factor needs adequate indicators and sample size to converge [36]. Our SEM models did not contain any latent factors (all were observed measurements); therefore, a sample size smaller than 200 could be acceptable. (2) We used the bootstrapping method to estimate the coefficients of the SEM models. Based on the bootstrapping method, the estimates were robust even in a relatively small sample size. (3) Some researchers have argued that when the variables in SEM are reliable, the effects are strong; the SEM model is not overly complex, so a smaller sample is sufficient [37, 38]. Even a sample size of 50 was proposed by Iacobucci (2010) [39]. However, we agree with the recommendation of previous studies [30, 40] and suggest that future studies use a sample size of at least 200 to validate our results. Even though we recruited women at least 6 months but no more than 2 years post diagnosis, the variations in regard to month since diagnosis was not big. Previous studies have demonstrated that month since diagnosis could be a confounding factor influencing women’s body image [41]. Considering this factor in the path analysis would be helpful to validate the causal relationship. Because women’s marital coping patterns were not measured before diagnosis, we do not know if these women’s reports were specific to their disease or whether they reflected an existing pattern of coping with stress; the average number of years married was 29, and they were likely to have deep-seated patterns related to coping efforts. Future research can attempt to better understand the marital coping of partners in order to examine both members’ coping efforts related to their sexual relationship. Additionally, cancer and non-cancer-related communication will result in different distress levels among women with breast cancer during adjuvant therapy [42]. Future researchers may wish to add more instruction for women by which they can evaluate their coping efforts focused on cancer-related conflicts.

Conclusions

This study elucidates the mediating effect of negative marital coping efforts, specifically avoidance and self-blame, in the relationship between body image and sexual relationship. Couple-based interventions to improve sexual relationships in women with breast cancer need to cultivate appropriate coping strategies to help women facing or managing marital conflict. Interventions simultaneously improving women’s body image problems will be essential for their sexual relationships because body image changes may intensify engagement in negative marital coping behavior.

References

GLOBOCAN (2014) Estimated cancer incidence, mortality and prevalence worldwide in 2012. World Health Organization. http://globocan.iarc.fr/Pages/Editors.aspx. Accessed 22, Apr. 2014

Howlader N, Noone A, Krapcho M, Neyman N, Aminou R, Waldron W, Altekruse S, Kosary C, Ruhl J, Tatalovich Z (2011) SEER cancer statistics review, 1975–2008. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute 19

Emilee G, Ussher J, Perz J (2010) Sexuality after breast cancer: a review. Maturitas 66(4):397–407

Hill EK, Sandbo S, Abramsohn E, Makelarski J, Wroblewski K, Wenrich ER, McCoy S, Temkin SM, Yamada SD, Lindau ST (2011) Assessing gynecologic and breast cancer survivors’ sexual health care needs. Cancer 117(12):2643–2651

Manganiello A, Hoga LAK, Reberte LM, Miranda CM, Rocha CAM (2011) Sexuality and quality of life of breast cancer patients post mastectomy. Eur J Oncol Nurs 15(2):167–172

Fobair P, Stewart SL, Chang S, D'Onofrio C, Banks PJ, Bloom JR (2006) Body image and sexual problems in young women with breast cancer. Psycho-oncology 15(7):579–594. doi:10.1002/pon.991

Berterö C, Wilmoth MC (2007) Breast cancer diagnosis and its treatment affecting the self: a meta-synthesis. Cancer Nurs 30(3):194–202

Andersen BL (2009) In sickness and in health: maintaining intimacy after breast cancer recurrence. Cancer J (Sudbury, Mass) 15(1):70

Garrusi B, Faezee H (2008) How do Iranian women with breast cancer conceptualize sex and body image? Sex Disabil 26(3):159–165

Speer JJ, Hillenberg B, Sugrue DP, Blacker C, Kresge CL, Decker VB, Zakalik D, Decker DA (2005) Study of sexual functioning determinants in breast cancer survivors. Breast J 11(6):440–447. doi:10.1111/j.1075-122X.2005.00131.x

Ganz PA, Desmond KA, Belin TR, Meyerowitz BE, Rowland JH (1999) Predictors of sexual health in women after a breast cancer diagnosis. J Clin Oncol: Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol 17(8):2371–2380

Reese JB, Keefe FJ, Somers TJ, Abernethy AP (2010) Coping with sexual concerns after cancer: the use of flexible coping. Support Care Cancer 18(7):785–800

Kinsinger SW, Laurenceau J-P, Carver CS, Antoni MH (2011) Perceived partner support and psychosexual adjustment to breast cancer. Psychol Health 26(12):1571–1588

Northouse LL, Katapodi MC, Schafenacker AM, Weiss D (2012) The impact of caregiving on the psychological well-being of family caregivers and cancer patients. Semin Oncol Nurs 28(4):236–245

Kayser K, Scott JL (2008) Helping couples cope with women’s cancers, vol 229. Springer,

Skerrett K (1998) Couple adjustment to the experience of breast cancer. Families, systems, & health 16 (3):281

Zunkel G (2003) Relational coping processes: couples’ response to a diagnosis of early stage breast cancer. J Psychosoc Oncol 20(4):39–55

Krueger DW (2004) Psychodynamic perspectives on body image. In: Cash TF, Pruzinsky T (eds) Body image: a handbook of theory, research, and clinical practice. The Guilford Press, New York, pp 30–37

Crompvoets S (2006) Comfort, control, or conformity: women who choose breast reconstruction following mastectomy. Health Care Women Int 27(1):75–93. doi:10.1080/07399330500377531

Fang SY, Balneaves LG, Shu BC (2010) “A struggle between vanity and life”: the experience of receiving breast reconstruction in women of Taiwan. Cancer Nurs 33(5):E1–E11. doi:10.1097/NCC.0b013e3181d1c853

Yurek D, Farrar W, Andersen BL (2000) Breast cancer surgery: comparing surgical groups and determining individual differences in postoperative sexuality and body change stress. J Consult Clin Psychol 68(4):697–709

Badr H, Carmack CL, Kashy DA, Cristofanilli M, Revenson TA (2010) Dyadic coping in metastatic breast cancer. Health Psychol 29(2):169

Fang SY, Chang HT, Shu BC (2014) The links of objectified body consciousness, body image discomfort, and depressive symptoms among breast cancer survivors in Taiwan. Psychol Women Quart 38(4):563–574

Scott JL, Halford WK, Ward BG (2004) United we stand? The effects of a couple-coping intervention on adjustment to early stage breast or gynecological cancer. J Consult Clin Psychol 72(6):1122–1135. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.72.6.1122

Norton TR, Manne SL, Rubin S, Hernandez E, Carlson J, Bergman C, Rosenblum N (2005) Ovarian cancer patients’ psychological distress: the role of physical impairment, perceived unsupportive family and friend behaviors, perceived control, and self-esteem. Health Psychol: Off J Div Health Psychol Am Psychol Assoc 24(2):143–152. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.24.2.143

Bowman ML (1990) Coping efforts and marital satisfaction: measuring marital coping and its correlates. J Marriage Fam 52:463–474

Lee LJ (1997) Model testing of the process of marital coping behavior. J Chengchi Univ 74:53–94

Berglund G, Nystedt M, Bolund C, Sjödén P-O, Rutquist L-E (2001) Effect of endocrine treatment on sexuality in premenopausal breast cancer patients: a prospective randomized study. J Clin Oncol 19(11):2788–2796

Taylor‐Brown J, Kilpatrick M, Maunsell E, Dorval M (2000) Partner abandonment of women with breast cancer: myth or reality? Cancer Pract 8(4):160–164

Kline RB (2011) Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. The Guilford Press, London

Lt H, Bentler PM (1999) Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Model: Multidiscip J 6(1):1–55

Fu MR, Xu B, Liu Y, Haber J (2008) ‘Making the best of it’: Chinese women’s experiences of adjusting to breast cancer diagnosis and treatment. J Adv Nurs 63:155–165

Ashing-Giwa KT, Padilla G, Tejero J, Kraemer J, Wright K, Coscarelli A, Clayton S, Williams I, Hills D (2004) Understanding the breast cancer experience of women: a qualitative study of African American, Asian American, Latina and Caucasian cancer survivors. Psycho-oncol 13:408–428

Giese-Davis J, Hermanson K, Koopman C, Weibel D, Spiegel D (2000) Quality of couples’ relationship and adjustment to metastatic breast cancer. J Fam Psychol 14(2):251

Scott JL, Kayser K (2009) A review of couple-based interventions for enhancing women's sexual adjustment and body image after cancer. Cancer J 15(1):48–56. doi:10.1097/PPO.1090b1013e31819585df

Anderson J, Gerbing D (1984) The effect of sampling error on convergence, improper solutions, and goodness-of-fit indices for maximum likelihood confirmatory factor analysis. Psychometrika 49(2):155–173

Bearden WO, Sharma S, Teel JE (1982) Sample size effects on chi square and other statistics used in evaluating causal models. J Mark Res 19(4):425–430

Bollen KA (1990) Overall fit in covariance structure models: two types of sample size effects. Psychol Bull 107(2):256–259

Iacobucci D (2010) Structural equations modeling: fit indices, sample size, and advanced topics. J Consum Psychol 20(1):90–98

Su CT, Ng HS, Yang AL, Lin CY (2014) Psychometric evaluation of the Short Form 36 Health Survey (SF-36) and the World Health Organization Quality of Life Scale Brief Version (WHOQOL-BREF) for patients with schizophrenia. Psychol Assess 26(3):980–989

Boquiren VM, Esplen MJ, Wong J, Toner B, Warner E (2013) Exploring the influence of gender‐role socialization and objectified body consciousness on body image disturbance in breast cancer survivors. Psycho‐Oncol 22:2177–2185

Manne S, Sherman M, Ross S, Ostroff J, Heyman RE, Fox K (2004) Couples’ support-related communication, psychological distress, and relationship satisfaction among women with early stage breast cancer. J Consult Clin Psychol 72(4):660–670. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.72.4.660

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the Ditmanson Medical Foundation Chia-Yi Christian Hospital of Taiwan for its support of this study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest. The authors have full control of all primary data and agree to allow the journal to review the data if required.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fang, SY., Lin, YC., Chen, TC. et al. Impact of marital coping on the relationship between body image and sexuality among breast cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer 23, 2551–2559 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-015-2612-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-015-2612-1