Abstract

Purpose

Cutaneous adverse events induced by epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) inhibitors can hamper the patients' quality of life. The aim of our work was to draft an algorithm for the optimised management of this skin toxicity.

Methods

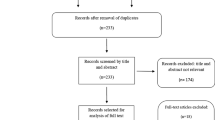

This algorithm was built in three steps under the responsibility of a steering committee. Step I: a systematic literature analysis (SLA) has been performed. Step II: the collection of information about practices was performed through a questionnaire.These questions were asked during regional meetings to which oncologists, gastro-enterologists, radiotherapists, and dermatologists were invited. Step III: a final meeting was organised involving the bibliography group and the steering committee and regional scientific committees for proposing a final algorithm.

Results

Step I: 14 publications were selected to evaluate the use of cyclines as curative or prophylactic treatment of the folliculitis induced by EGFR inhibitors. Nineteen publications were retained for the topical treatment of the folliculitis. Forty-six articles were selected for the management of the cutaneous lesions in link with appendages and 12 for xerosis and pruritus. Step II: 96 delegates attended the seven regional meetings and 67 questionnaires were analysed. Step III: a final algorithm was proposed on the basis of the conclusions of the first two steps and expert opinions present at this final meeting. The different propositions were unanimously approved by the 14 experts who voted.

Conclusions

This multidisciplinary study summarising published data and current practices produced a therapeutic algorithm, which should facilitate the standardised, optimised management of skin toxicity associated with EGFR inhibitors in France.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) inhibitors have proven their efficacy in the management of advanced colorectal, lung cancers and squamous cell cancers of the head and neck by improving the survival rate of treated patients. This efficacy is, however, often associated with essentially dermatological side effects, which can significantly impact a patient's quality of life and thus hamper continued treatment. A greater understanding of these side effects and appropriate treatment regimens for this toxicity should optimise treatment acceptance and improve compliance.

A number of recommendations have recently been published in an attempt to specify the ways in which these skin-related side effects can be managed [1–15]. Nevertheless, management strategy is empirical and is usually based on personal prescription patterns. The aim of our work was to draft a therapeutic algorithm to manage EGFR inhibitor-induced skin lesions, thus creating a structured management framework and harmonised practices.

Method

Our work began in May 2010 with the creation of a multidisciplinary steering committee comprising two gastrointestinal oncologists, one radiotherapist and one dermatologist (chairman). This committee defined the methodology with three steps permitting to reach a final algorithm based both on evidence-based medicine and clinical experience of both oncologists and dermatologists.

Step I

A bibliographical study group composed by three dermatologists and one oncologist initially carried out a systematic review of relevant published data. This systematic literature analysis (SLA) was carried out in accordance with the Cochrane Collaboration Guidelines [16].

The search strategy was compiled with the help of an experienced librarian. Three electronic databases, Pubmed, Embase and Cochrane (central register of randomised controlled trials), were searched simultaneously in November 2010. The clinical questions to be assessed by the systematic review were defined on the basis of the types of skin lesions caused by EGFR inhibitors, starting from the anatomical structures of the skin which were involved: (1) the pilo-sebaceous follicle for folliculitis; (2) the skin barrier for xerosis and fissures, and eczema; and (3) the cutaneous appendages: nails and hairs. The searches were structured in the form of key words relating to EGFR inhibitor treatments and their cutaneous adverse events (“EGFR inhibitor”, “anti-epidermal growth factor”, “cetuximab”, “panitumumab”, “erlotinib” and “gefitinib”) and skin toxicity study (“skin toxicity”, “rash”, “”acne”, “acneiform”, “nail”, “paronychia”, “hair”, “alopecia”, “hirsutism”, “hypertrichosis”, “trichomegaly”, “xerosis”, “pruritus” and “itch”). On completion of this electronic search, a manual search using the references quoted in the articles allowed additional publications to be extracted. Only articles written in English and French were selected. The literature reviews, recommendations or consensus conference and the series of clinical cases for which the treatment or clinical course was unclear were not included in our analysis. The methodological quality of the selected articles was subjected to an evidence-based analysis, as defined by the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine [17].

Step II

The collection of information about practices was performed through a questionnaire of 31 questions compiled by the steering committee, and the questions referred to the management of ten current clinical situations put forward in the context of prescribing an EGFR inhibitor (prevention, slight folliculitis, severe folliculitis, superinfected folliculitis, xerosis and skin fissures, paronychia, trichomegaly, scalp lesions and associated radiodermatitis). These questions were asked during regional meetings to which oncologists, gastro-enterologists, radiotherapists and dermatologists were invited. Regional meetings were held between November 2010 and January 2011 in seven French towns/cities (Paris, Reims, Strasbourg, Lyon, Rennes, Toulouse and Aix-en-Provence). A regional scientific committee (RSC) comprising three to five local experts, each one representing the medical specialty involved, chaired these meetings. The questionnaires, completed outside discussions, highlighted the prescription patterns of the 79 practitioners who attended. The answers given in the questionnaires were assessed by descriptive analysis taking the objective into account for those participants who were not dermatologists. The dermatologists were only involved in the post-questionnaire discussion of the clinical cases.

Step III

In May 2011, a national meeting was held over 1.5 days. The aim of this meeting was to build an algorithm for the management of cutaneous adverse event-induced EGFR inhibitors according to their severity, taking into account both the literature (systematic review performed by the bibliographic study group) and the clinical experience (collected during regional meetings). The 20 members of this meeting were the steering committee, chairs of the regional meetings and bibliographic study group. After 1 day of discussions between the experts, the final algorithm was proposed by the steering committee trying to respect the most independent and objective approach, making a distinction between what constituted scientific proof, general facts and empirical practice. The algorithm was, therefore, put forward for presentation the next day to all experts and assessed using a democratic voting system. Their approval was measured on a scale ranging from 1 (no approval whatsoever) to 10 (full approval given).

Results

Step I: review of the literature

Folliculitis

Forty-three publications were screened to evaluate the use of cyclines as curative or prophylactic treatment of the folliculitis induced by the EGFR inhibitors. Amongst these, 29 were excluded (guidelines, unclear outcome…). Fourteen publications were definitely selected. Four randomised trials [18–21] evaluated the use of cyclines for the prevention of the onset of folliculitis. Only one study (STEPP) [18] was positive in terms of its primary objective, which was to reduce the incidence of grades 2–3 folliculitis during the first 6 weeks of treatment. The level of evidence of these studies is II.

No randomised study investigated the efficacy of cyclines as curative treatment for folliculitis; seven publications of one to four clinical cases and three non-randomised, prospective series of 11 to 24 patients reported the results of curative treatment with minocycline, doxycycline or tetracycline in conjunction with different local topical agents to varying degrees [22–25]. Cycline treatment with or without topical treatment was reported to be effective and associated with a reduction in the grade of folliculitis. The level of evidence of these articles is IV.

Regarding other topical treatments (corticoids, tazarotene, pimecrolimus, antibiotics…), 43 publications were initially selected. Twenty-four were excluded (insufficient data, unclear outcome…). Nineteen publications were finally retained: three randomised studies [18, 21, 26] and numerous case series with extremely heterogeneous management strategies combining local treatments or local and systemic treatments. Topical corticosteroids are considered efficient as curative treatment. There is no solid data evaluating the interest of hydrocortisone or any other local topical corticosteroids alone for the prevention of cutaneous adverse events induced by EGFR inhibitors. Randomised trials showed tazarotene [21] and pimecrolimus [26] to be ineffective for the treatment of the folliculitis.

Cutaneous lesions in link with appendages

In the case of paronychia and pyogenic granulomas: 24 articles were selected. Only the STEPP study [18] focused on the efficacy of prophylactic treatment. Its aim was to assess a treatment combining emollients, 1 % hydrocortisone applied to the hands and feet once a day, and advice on preventing irritation using an audiovisual document and doxycycline at the dose of 2 × 100 mg/day. At 6 weeks, the onset of paronychia was observed in 17 % of patients in this treated group versus 36 % in the second group, the difference being statistically significant. Amongst the 23 articles focusing on the curative efficacy of treatment, we did not find any randomised study. The cases presented were small, open-label, prospective or retrospective observational studies including only one to six cases of paronychia and one microbiological study including 29 patients [27].

Concerning hair abnormalities, 22 articles about hypertrichosis and trichomegaly and six focusing on alopecia were selected. They were isolated clinical cases. Specific prophylactic treatment was never proposed for any of these undesirable effects. The treatment of hirsutism, hypertrichosis and trichomegaly was symptomatic [28, 29]. No curative treatment of alopecia was mentioned.

Cutaneous lesions in link with the skin barrier and pruritus

No study has been carried out to assess the efficacy and interest of the treatments proposed in the management of skin xerosis or pruritus. Twelve articles were selected and analysed. The clinical cases published involved between 16 and 33 patients. Emollient are generally recommended. Recently, Vincenzi et al. [30] reported a possible interest in the use outside MA indications of the anti-emetic aprepitant in erlotinib-induced pruritus. The level of evidence of this literature is low, IV.

Step II: collection of information about current practices in daily practice

Ninety-six delegates, including 12 dermatologists, attended the seven regional meetings. Sixty-seven questionnaires, completed by 33 oncologists, 31 gastro-enterologist and three radiotherapists, were analysed. In preventive treatment, moisturising and cyclines were recommended by the majority of practitioners (63 % and 62 %, respectively). In curative treatment, a consensus approach was adopted, especially for uncomplicated cases of folliculitis. Differences mainly appeared in the treatment of less typical cases. The referral to a dermatologist is low. It was not envisaged at the moment of introduction of EGFR inhibitors. Once lesion appeared, only 43.3 % of practitioners proposed a dermatology visit motivated by a significant psychological or functional impact and 40.3 % because a secondary infection was either present or suspected. The behaviour concerning the interruption or continuation of EGFR inhibitors was uniform for mild lesions (grade I); conversely, for the more severe cases of folliculitis (grades II and III) or specific cases combined with radiodermatitis, the approach was less clear-cut.

Step III: therapeutic algorithm

The algorithm is composed of five parts summarised in five tables: prevention treatment (Table 1), then three parts for the treatment of cutaneous lesions in link with either pilo-sebaceous follicle, or appendages or skin barrier and finally in the fifth part is given the treatment of cutaneous lesions after combined therapy with anti-EGFR and radiotherapy. Except for prevention, the treatment proposed took into account of the severity of cutaneous lesions according to three grades based on the classification currently used in clinical trials, The National Cancer Institute's Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (NCI-CTCAE) version 4.0 [31]. Regarding paronychia, the expert panel deemed that this classification was inappropriate and proposed a more suitable segmentation.

All of our recommendations are level IV in terms of expert opinion (EO) apart from the recommendation regarding doxycyclines on introducing EGFR inhibitor treatment, which constitutes level II. The different propositions were unanimously approved by the 14 experts who voted. The level of acceptance was very high, ranging from 9.10 to 9.85.

Preventive measures recommended on introduction of EGFR inhibitors (Table 1)

Based on literature it is recommended, simultaneously to the introduction of EGFR inhibitors, to prescribe cyclines at 200 mg/day and a daily use of moisturing cream. Many accompanying care including measures that are not recommended and should be avoided are summarised in Table 1; they were mainly based on expert opinion.

Cutaneous lesions in link with pilo-sebaceous follicle (Table 2)

On the basis of the SLA and expert opinion, it is recommended to treat folliculitis by keeping cyclines at the same dosage as prescribed in prophylactic therapy until symptoms disappear. Minocycline is proposed as the second line on an expert consensus based on the experience of dermatologists at a dosage similar to acne: 100 mg/day.

Amongst the other dermatological treatments, only topical steroids were selected, based on expert consensus. The strength of the corticoid should be adapted depending on the degree of severity of the folliculitis. Thus, class III (strong) and class IV (very strong) corticoids are reserved solely for grade 3. The facial application of a class IV corticoid is contraindicated.

Cutaneous lesions in link with appendages (Table 3)

The paronychia was classified by the steering committee according to three grades (asymptomatic, moderate, severe and affecting daily routine), depending on the extent to which they impact a person's lifestyle. For the three grades, class IV (very strong) topical steroids are proposed in the absence of secondary infection, combined with systemic antibiotic therapy with cyclines, which is continued until symptoms disappear (expert consensus). In severe form, grade 3, with secondary infection confirmed with a swab, considers a consultation with a dermatologist.

In the case of pyogenic granuloma, a treatment initiated by dermatologists as silver nitrate, electrocoagulation and intralesional corticoid injections under local anaesthesia and CO2 laser at his/her fingertips is recommended. In the case of hirsutism-related problems, symptomatic treatment is considered in the event of excessive problematic hair coverage: bleaching, hair removal using a non-aggressive method (tweezers, laser, LED and avoiding wax) or topical eflornithine (expert consensus). In the case of trichomegaly of the lashes, cautious cutting with a pair of scissors is recommended (expert consensus).

Cutaneous lesions in link with the skin barrier—xerosis (Table 4)

The treatment proposed is based on dermo-cosmetic with a foaming soap respecting the acid pH of the skin and a moisturizing cream. Preference is given to greasy emollients for the treatment of more severe forms of xerosis.

Radiodermatitis associated with folliculitis (Table 5)

The approach to adopt for the management of radiodermatitis in the presence of EGFR inhibitor-induced folliculitis differs from that used for conventional radiodermatitis. In this case, it is recommended to take the grade of the folliculitis lesion into account in addition to that of the radiodermatitis so as to adjust anti-cancer treatment, EGFR inhibitor chemotherapy and radiotherapy, in particular. The experts recommended a strategy for cancer treatment (radiotherapy and EGFR inhibitors) driven by the severity of both radiodermitis and folliculitis.

Discussion

Previously published recommendations were approved by national and international learned societies and mostly multidisciplinary expert groups. Their methodology varied, but they were mostly based on expert opinions relying, in turn, on published data (Table 6).

On the one hand, our methodology differed from the expert opinion since an SLA was carried out for folliculitis-, xerosis- and appendage-related problems. On the other hand, an upstream evaluation of current French practices was initiated. Based on our knowledge, it's the first time that such a practice survey has been performed in order to build an algorithm. The SLA allowed numerous publications to be selected and analysed, but it should be noted that the evidence base is generally very poor: only a few randomised trials assessed the management of skin lesions.

Finally, our methodology has allowed more specialists to be involved, since regional meetings brought together 96 practitioners. A total of 20 were able to participate in the summary meeting and in drafting final recommendations with a focus on the practical management of anti-EGFR-induced skin toxicity including medical treatment and cosmetic dermatology procedures.

Few data are actually available regarding the approach vis-à-vis EGFR inhibitors in the case of skin toxicity in clinical trials: dose reduction, even treatment withdrawal. A dose reduction is mentioned in less than 5 % of trials reporting this fact; however, a practical survey on EGFR inhibitor-induced skin toxicity reported much higher figures of 60 % and 32 % in relation to dose reduction and treatment withdrawal, respectively [32]. No published data has evaluated the impact of a reduction in EGFR inhibitor dose levels on the clinical course of an induced skin lesion. Data requiring further investigation should, therefore, be specified in future trials.

A multidisciplinary approach is recognised as essential by most of the teams involved in the recommendations. According to the data collated for French practices, it seems that dermatology consultations are far from routine. The absence of any structure allowing straightforward access to a specialist consultation could account for this low percentage. At the same time, increasing numbers of oncologists now feel that they have sufficient feedback to manage these lesions independently. Some semiological or progressive factors must motivate patients to seek a dermatological consultation. The list is not exhaustive but the main reasons are as follows: lack of improvement after 1 to 2 weeks of appropriate treatment, severe clinical signs (necrosis, blisters, purpura, etc.), secondary infection, atypical clinical signs that could be indicative of dermatitis not related to EGFR inhibitor treatment (differential diagnosis) and severe nail diseases such as pyogenic granuloma, which may warrant specific treatments.

Conclusion

This is the first therapeutic algorithm for the cutaneous adverse events of anti EGFR, which is the result of a consensus between the evidence-based medicine with the SLA and current clinical practice, finally, validated by a vote. It is also interesting that it is the result of a discussion between both oncologists and dermatologists. It is based on a practical severity and combined recommendations not only for drugs but also for cosmetic. They are geared primarily towards the introduction of clearly defined products for the optimised, standardised management of patients receiving EGFR inhibitors by all practitioners involved. The SLA has clearly highlighted the lack of randomised studies for the clear-cut evaluation of the various curative treatments prescribed for induced skin lesions.

References

Segaert S, Tabernero J, Chosidow O et al (2005) The management of skin reactions in cancer patients receiving epidermal growth factor receptor targeted therapies. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 3:599–606

Segaert S, Van Cutsem E (2007) Clinical management of EGFRI dermatologic toxicities: the European perspective. Oncology (Williston Park) 21:S22–S26

Melosky B, Burkes R, Rayson D et al (2009) Management of skin rash during EGFR-targeted monoclonal antibody treatment for gastrointestinal malignancies: Canadian recommendations. Curr Oncol 16:14–24

Eaby B, Culkin A, Lacouture ME (2008) An interdisciplinary consensus on managing skin reactions associated with human epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors. Clin J Oncol Nurs 12:283–290

Lacouture ME, Maitland ML, Segaert S et al (2010) A proposed EGFR inhibitor dermatologic adverse event-specific grading scale from the MASCC skin toxicity study group. Support Care Cancer 18:509–522

Lacouture ME, Cotliar J, Mitchell EP (2007) Clinical management of EGFRI dermatologic toxicities: US perspective. Oncology (Williston Park) 21(11 Suppl 5):17–21

Lacouture ME, Anadkat MJ, Bensadoun R-J, Bryce J, Chan A, Epstein JB, Eaby-Sandy B, Murphy BA (2011) Clinical practice guidelines for the prevention and treatment of EGFR inhibitor-associated dermatologic toxicities. Support Care Cancer 19:1079–1095

Duvic M (2008) EGFR inhibitor-associated acneiform folliculitis: assessment and management. Am J Clin Dermatol 9:285–294

Bernier J, Bonner J, Vermoken JB et al (2008) Consensus guidelines for the management of radiation dermatitis and coexisting acne-like rash in patients receiving radiotherapy plus EGFR inhibitors for the treatment of squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Ann Oncol 19:142–149

Fox LP (2006) Pathology and management of dermatologic toxicities associated with anti-EGFR therapy. Oncology (Williston Park) 20:26–34

Gridelli C, Maione P, Amoroso D et al (2008) Clinical significance and treatment of skin rash from erlotinib in non-small cell lung cancer patients: results of an Experts Panel Meeting. Crit Rev Hematol 66:156–162

Hu JC, Sadeghi P, Pinter-Brown LC et al (2007) Cutaneous side effects of epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors: clinical presentation, pathogenesis, and management. J Am Acad Dermatol 56:317–326

Potthoff K, Hofheinz R, Hassel JC et al (2011) Interdisciplinary management of EGFR-inhibitor-induced skin reactions: a German expert opinion. Ann Oncol 22:524–535

Oishi KJ, Garey JS, Burke BJ et al (2006) Managing cutaneous side effects associated with erlotinib in head and neck cancer and non small lung cancer patient. J Clin Oncol 24:18s (abstract 18538)

Bouché O, Scaglia E, Reguiaï Z et al (2009) Biothérapies ciblées en cancérologie digestive: prise en charge de leurs effets secondaires. Gastroenterol Clin Biol 33:306–322

van Tulder M, Furlan A, Bombardier C et al (2003) Updated method guidelines for systematic reviews in the Cochrane Collaboration Back Review Group. Spine 28:1290–1299

Lacouture ME, Mitchell EP, Piperdi B et al (2010) Skin toxicity evaluation protocol with panitumumab (STEPP), a phase II, open-label, randomized trial evaluating the impact of a pre-emptive skin treatment regimen on skin toxicities and quality of life in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 28:1351–1357

Jatoi A, Rowland K, Sloan JA et al (2008) Tetracycline to prevent epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor-induced skin rashes: results of a placebo-controlled trial from the North Central Cancer Treatment Group (N03CB). Cancer 13:847–853

Deplanque G, Chavaillon J, Vergnenegre A et al (2010) CYTAR: A randomized clinical trial evaluating the preventive effect of doxycycline on erlotinib-induced folliculitis in non-small cell lung cancer patients. J Clin Oncol 28(No 15_suppl):A9019

Scope A, Agero AL, Dusza SW et al (2007) Randomized double-blind trial of prophylactic oral minocycline and topical tazarotene for cetuximab-associated acne-like eruption. J Clin Oncol 25:5390–5396

Wacker B, Nagrani T, Weinberg J et al (2007) Correlation between development of rash and efficacy in patients treated with the epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor erlotinib in two large phase III studies. Clin Cancer Res 13:3913–3921

Matheis P, Socinski MA, Burkhart C et al (2006) Treatment of gefitinib-associated folliculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol 55:710–713

Molinari E, De Quatrebarbes J, André T et al (2005) Cetuximab-induced acne. Dermatology 211:330–333

de Noronha e Menezes NM, Lima R et al (2009) Description and management of cutaneous side effects during erlotinib and cetuximab treatment in lung and colorectal cancer patients: a prospective and descriptive study of 19 patients. Eur J Dermatol 19:248–251

Scope A, Lieb JA, Dusza SW et al (2009) A prospective randomized trial of topical pimecrolimus for cetuximab-associated acnelike eruption. J Am Acad Dermatol 61:614–620

Amitay-Laish I, David M, Stemmer SM (2010) Staphylococcus coagulase-positive skin inflammation associated with epidermal growth factor receptor-targeted therapy: an early and a late phase of papulopustular eruptions. Oncologist 15:1002–1008

Vergou T, Stratigos AJ, Karapanagiotou EM et al (2010) Facial hypertrichosis and trichomegaly developing in patients treated with the epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor erlotinib. J Am Acad Dermatol 63:e56–e58

Bouché O, Brixi-Benmansour H, Bertin A et al (2005) Trichomegaly of the eyelashes following treatment with cetuximab. Ann Oncol 16:1711–1712

Vincenzi B, Tonini G, Santini D (2010) Aprepitant for erlotinib-induced pruritus. N Engl J Med 363:397–398

NCI Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) v4. ctep.cancer.gov/reporting/ctc.html

Boone SL, Rademaker A, Liu D et al (2007) Impact and management of skin toxicity associated with anti-epidermal growth factor receptor therapy: survey results. Oncology 72:152–159

Acknowledgments

This project and the authors were supported by a grant from Amgen France. We are grateful to the members of Laboratoires Amgen France for their support and to the experts whose knowledge and experience were crucial to the development of these recommendations. Thanks to the Regional experts groups “PROCUR” E. Achille, C. Borel, C. de la Fouchardière, P. Giraud, C. Lebbe, M.T. Leccia, L. Mortier, G. Reuter, J.P. Wagner.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

B. Dreno For equal work of the last author.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Reguiai, Z., Bachet, J.B., Bachmeyer, C. et al. Management of cutaneous adverse events induced by anti-EGFR (epidermal growth factor receptor): a French interdisciplinary therapeutic algorithm. Support Care Cancer 20, 1395–1404 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-012-1451-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-012-1451-6