Abstract

Background

Currently, whether laparoscopic or open splenectomy is a gold standard option for spleen abnormalities remains in controversy. There is in deficiency of academic evidence concerning the surgical efficacy and safety of both comparative managements. In order to surgically appraise the applied potentials of both approaches, we hence performed this comprehensive meta-analysis on the basis of 15-year literatures.

Methods

Via searching of PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, and Cochrane Library databases, overall 37 original articles were eligibly incorporated into our meta-analysis and subdivided into six sections. In accordance with the Cochrane Collaboration protocol, all statistical procedures were mathematically conducted in a standard manner. Publication bias was additionally evaluated by funnel plot and Egger’s test.

Results

Irrespective of the diversified splenic disorders, laparoscopic splenectomy was superior to open technique owing to its fewer estimated blood loss, shorter postoperative hospital stay as well as lower complication rate (P < 0.05). As for operative duration and perioperative mortality, a statistical similarity was observed amid both surgical measures (P > 0.05).

Conclusion

Technically, laparoscopic splenectomy should be recommended as a prior remedy with its advantage of rapid recovery and minimally physical damage, in addition to its comparably surgical efficacy against that of open manipulation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Surgical dissection serves as a therapeutic option for a variety of splenic disorders, especially for those refractory to medicated prescriptions, including congestive splenomegaly and idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP). A laparoscopic arm of splenectomy firstly emerged in 1991 and has been globally popularized over the past two decades [1]. The properties of minimal invasiveness and shortened recovery course mainly contribute to the widespread usage of laparoscopic splenectomy. Therefore, the surgeon community has recommended laparoscopic dissection as a standard manipulation for patients with nonsevere splenomegaly and benign general conditions. However, owing to insufficient operative experiences and technical restrictions, several circumstances including massive splenomegaly have been recognized as relative contraindications for laparoscopic splenectomy. It is quite challenging to make adequate exposure of the upper left quadrant of massive splenomegaly under laparoscope, let alone the hemorrhagic tendency derived from increasing platelet destruction [2, 3]. Hence, it has become a temporary technical dispute and attracts academic attentions among surgical pioneers.

At present, along with the accumulating experiences and innovative instruments, several surgical experts have made breakthroughs on addressing massive splenomegaly with laparoscopic arm and reported comparable benefits against open procedure [4, 5]. Moreover, since the publication of clinical guidelines of laparoscopic splenectomy in 2008 [2], numerous trials have been published to supplement the academic literatures on relevant themes. These reveal an urgent necessity to provide updates and potential alterations for practical guidelines. Therefore, through a high-volume literature retrieval of comparative investigations published during the past 15 years, a full-scale meta-analysis concerning the surgical options of various splenic dysfunctions was classically performed, wishing to offer novel insights of minimally invasive technique on spleen surgery.

Materials and methods

Search strategy

By electronically searching PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, and Cochrane Library databases, all retrieved studies published from 1999 to 2014 were preliminarily included for further screening. “Laparoscopic splenectomy AND open” was employed as search term in case of unexpected omission. Both abstracts and full texts were elaborately reviewed in order to guarantee the screening accuracy. Two authors independently implemented this procedure.

Study selection

Studies that met the following criteria were included for further analysis: (1) comparative trials concerning laparoscopic splenectomy versus open splenectomy for splenic disorders; (2) English-written and formally published articles ranging from 1999 to 2014; and (3) investigations that contained adequate original data of perioperative parameters.

Studies were excluded due to the following reasons: (1) literatures with a sample size <20 participants; (2) overlapped or duplicated studies; and (3) irrelevant operations were synchronously performed besides a single splenectomy;

The appraisal of eligibility was manipulated by two independent investigators. Any discrepancies were settled by mutual discussion.

Data extraction

With the aid of standardized extraction forms, two independent reviewers extracted original data from individual studies ahead of the pooled analysis. In order to avoid any artificial errors, a supervisor was designated to carefully scrutinize the whole process during data extraction.

Methodological quality assessment

Nonrandomized studies were methodologically assessed by Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS), which was constituted by three categories including selection, comparability, and outcome. Trials graded with six stars or more were identified as high quality in methodology. Details of the rating criteria were orderly listed in Supplementary Table S1.

Randomized trials were appraised via the revised Jadad’s Scale. Overall, four assessment categories consisted of the entire scale including randomization, allocation concealment, blindness, and statement of withdrawal. Studies assigned with four points or more were regarded as high-quality trials. Details of the judging requirements were demonstrated in Supplementary Table S2.

Two researchers, respectively, evaluated the quality of each study. Any disagreement was resolved via mutual discussion.

Statistical analysis

Review Manager 5.3 was utilized as a statistical platform of the pooled analysis. Weighted mean difference (WMD) and odds ratio (OR) were appropriate for continuous and dichotomous variables, respectively. The effect size was numerically displayed by 95 % confidence intervals (95 % CI). With regard to continuous data with medians and ranges instead of means and standard deviations (SD), we transformed it into means and SD following the equations provided by Hozo et al. [6]. Furthermore, if medians and interquartile range were offered, the medians were considered as means, and the interquartile range divided by 1.35 was statistically applied as standard deviations, which was described and approved by Cochrane Handbook. The statistical heterogeneity across studies was quantified by the magnitude of I 2. A fixed-effects model was adopted when I 2 was <25 %, indicating low substantial heterogeneity therein. Otherwise, a random-effects model was preferred for the remaining circumstances. Mathematically, P < 0.05 symbolized the significant difference within, while publication bias was graphically discussed by funnel plot and Egger’s test.

Results

Section 1: Overall analysis

Baseline features

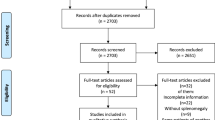

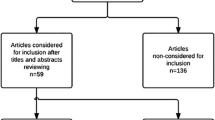

Eleven studies were eligibly included in the pooled analysis, which contained eight retrospective cohort studies, two prospective cohort studies, and one randomized controlled trial. Age, sex ratio, body mass index (BMI), and spleen weight were four baseline parameters to measure the internal comparability amid included studies (Table 1). Methodological assessment scores of each article are listed in Supplementary Table S3 for nonrandomized studies and Supplementary Table S4 for randomized studies, respectively. The stepwise selection process is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Intra-operative blood loss

Patients undergoing laparoscopic splenectomy had less intra-operative blood loss compared to those of open surgery (n = 5, WMD: −217.67 ml, 95 % CI −325.07 to −110.27, P < 0.0001, I 2 = 99 %; Fig. 2A).

Operation time

The statistical outcome revealed that both techniques shared a similar operation time without significant difference (n = 7, WMD: 19.30 min, 95 % CI −39.36 to 77.96, P = 0.52, I 2 = 97 %; Fig. 2B).

Postoperative hospital stay

Laparoscopic intervention could significantly shorten the postoperative hospital stay than open arm (n = 9, WMD: −2.10 days, 95 % CI −2.84 to −1.36, P < 0.00001, I 2 = 92 %; Fig. 2C).

Overall complication rate

On the basis of the pooled analysis, the complication rate after laparoscopic splenectomy was significantly lower than that of open manipulation (n = 5, OR 0.44, 95 % CI 0.36–0.54, P < 0.00001, I 2 = 0 %; Fig. 2D).

Perioperative mortality rate

There was no significant difference between both groups in terms of perioperative mortality rate (n = 2, OR 0.87, 95 % CI 0.09–8.43, P = 0.90, I 2 = 56 %; Fig. 2E).

Section 2: Hematologic disorders

Demographic characteristics

Four original investigations were selected for further pooled analysis, among which three cohorts were retrospectively studied. Age, sex proportion, malignancy ratio, and spleen weight were chosen as indicators to appraise the internal comparability within included studies (Table 2). All of the four articles displayed good comparability, along with details of methodological assessment listed in Supplementary Table S5.

Intra-operative blood loss

The estimated blood loss under laparoscope was significantly lower than that of open splenectomy (n = 2, WMD: −102.47 ml, 95 % CI −152.65 to −52.29, P < 0.0001, I 2 = 0 %; Fig. 3A).

Operation time

The overall operation time was nearly identical in both groups, according to our statistical analysis (n = 3, WMD: 0.66 min, 95 % CI −69.02 to 70.34, P = 0.99, I 2 = 95 %; Fig. 3B).

Postoperative hospital stay

Laparoscopic splenectomy was a more effective technique in accelerating the postoperative recovery than open dissection (n = 4, WMD: −2.15 days, 95 % CI −2.68 to −1.62, P < 0.00001, I 2 = 0 %; Fig. 3C).

Overall complication rate

There was much lower incidence of complications in patients undergoing laparoscopic management, rather than open surgery participants (n = 3, OR 0.36, 95 % CI 0.16–0.84, P = 0.02, I 2 = 30 %; Fig. 3D).

Section 3: Massive splenomegaly

General information

Five original cohorts were eventually enrolled with retrospective properties. By analyzing the baseline elements of age, sex ratio, malignancy ratio, and spleen length, favorable comparability was observed internally (Table 3). Details of methodological assessment scores are displayed in Supplementary Table S6.

Intra-operative blood loss

It was mathematically confirmed that laparoscopic splenectomy culminated in significantly less blood loss during operating process (n = 4, WMD: −168.37 ml, 95 % CI −312.78 to −23.96, P = 0.02, I 2 = 88 %; Fig. 4A).

Operation time

Regardless of surgical techniques, there was no significant difference in terms of operative duration (n = 5, WMD: 10.13 min, 95 % CI −32.85 to 53.10, P = 0.64, I 2 = 92 %; Fig. 4B).

Postoperative hospital stay

Laparoscopic splenectomy resulted in a significantly shorter hospital stay against open surgery (n = 5, WMD: −4.14 days, 95 % CI −5.58 to −2.70, P < 0.00001, I 2 = 68 %; Fig. 4C).

Overall complication rate

Patients undergoing laparoscopic dissection suffered lower incidence of complications in comparison with those of open arm (n = 5, OR 0.53, 95 % CI 0.30–0.94, P = 0.03, I 2 = 0 %; Fig. 4D).

Section 4: Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura

Background characteristics

A total of seven cohorts were pooled into the subgroup analysis, all of which were carried out in a retrospective manner. Including age, sex ratio, preoperative platelet count, and spleen length, the preliminary analysis of baseline parameters resulted in a favorable comparability amid eligible trials (Table 4). The detailed assessment scores are listed in Supplementary Table S7.

Intra-operative blood loss

Compared with laparoscopic intervention, open splenectomy led to more blood loss during operations by our pooled analysis (n = 4, WMD −174.30 ml, 95 % CI −284.74 to −63.86, P = 0.002, I 2 = 95 %; Fig. 5A).

Operation time

As described in the pooled analysis, both surgical techniques spent comparable operating time without significant difference (n = 7, WMD: 13.59 min, 95 % CI −38.51 to 65.68, P = 0.61, I 2 = 99 %; Fig. 5B).

Postoperative hospital stay

With respect to the restoration of postoperative patients, laparoscopic management caused a beneficially shorter hospital stay against open splenectomy (n = 6, WMD: −4.86 days, 95 % CI −7.47 to −2.26, P = 0.0003, I 2 = 96 %; Fig. 5C).

Overall complication rate

In contrast to open surgery, patients undergoing laparoscopic dissection had a significant less probability to suffer from postoperative complications (n = 5, OR 0.36, 95 % CI 0.18–0.73, P = 0.005, I 2 = 52 %; Fig. 5D).

Three-year complete remission rate

Irrespective of surgical types, patients of both groups exhibited a comparable 3-year complete remission rate according to our meta-analysis (n = 4, OR 0.93, 95 % CI 0.53–1.63, P = 0.79, I 2 = 15 %; Fig. 5E).

Section 5: Children sickle cell disease

Demographic features

Original data from three retrospective cohorts were extracted for pooled analysis. Age, sex ratio, and spleen weight were identified as internal indicators for comparability appraisal. The contrastive groups in each trial displayed well internal comparability (Table 5), while the assessment scores are additionally demonstrated in Supplementary Table S8.

Operation time

There was no significant difference between both operative approaches regarding the surgical duration (n = 2, WMD: 49.33 min, 95 % CI −37.86 to 136.52, P = 0.27, I 2 = 96 %; Fig. 6A).

Postoperative hospital stay

Laparoscopic splenectomy served as a more efficient technique in decreasing postoperative hospital stay against open surgery (n = 3, WMD: −1.68 days, 95 % CI −2.47 to −0.89, P < 0.0001, I 2 = 34 %; Fig. 6B).

Overall complication rate

In comparison with open dissection, laparoscopic technique led to lower occurrence of complications based on our pooled outcome (n = 3, OR 0.20, 95 % CI 0.06–0.69, P = 0.01, I 2 = 54 %; Fig. 6C).

Section 6: Portal hypertension

Basic characteristics

A total of seven investigations were included for this subgroup pooled analysis, containing one prospective and six retrospective cohorts. General parameters including age, sex ratio, Child-Pugh scores, and spleen length were identified as evaluation indicators of internal comparability. All of the seven studies display favorable comparability in (Table 6). In addition, details of assessment scores are listed in Table S9.

Intra-operative blood loss

The pooled outcome suggested that patients undergoing laparoscopic dissection suffered less blood loss than those of open surgery (n = 7, WMD: −200.87 ml, 95 % CI −239.84 to −161.89, P < 0.00001, I 2 = 84 %; Fig. 7A).

Analysis of portal hypertension. A Intra-operative blood loss; B operation time; C postoperative hospital stay; D overall complication rate; E White blood cell count at 7 days after surgery; F Hemoglobin level at 7 days after surgery; G platelet count at 7 days after surgery; H Total bilirubin level at 7 days after surgery; I ALT level at 7 days after surgery; J AST level at 7 days after surgery. LS laparoscopic splenectomy, OS open splenectomy

Operation time

It was mathematically verified that both techniques spent comparable time during surgical operations (n = 7, WMD: 13.87 min, 95 % CI −13.02 to 40.75, P = 0.31, I 2 = 84 %; Fig. 7B).

Postoperative hospital stay

Patients undergoing laparoscopic management were hospitalized for a significantly shorter period of time than those of open splenectomy (n = 7, WMD: −3.69 days, 95 % CI −4.75 to −2.63, P < 0.00001, I 2 = 67 %; Fig. 7C).

Overall complication rate

The pooled analysis reported that fewer complications occurred in laparoscopic group than open surgery (n = 6, OR 0.31, 95 % CI 0.19–0.51, P < 0.00001, I 2 = 0 %; Fig. 7D).

White blood cell count at 7 days after surgery

In accordance with the pooled result, the white blood cell count at 7 days after surgery was statistically identical between both surgical measures (n = 5, WMD: 1.83 × 109/l, 95 % CI −2.87 to 6.54, P = 0.44, I 2 = 98 %; Fig. 7E).

Hemoglobin level at 7 days after surgery

There was no significant difference between laparoscopic and open splenectomy in terms of hemoglobin level at 7 days after surgery (n = 2, WMD: 11.82 g/dl, 95 % CI −4.50 to 28.14, P = 0.16, I 2 = 48 %; Fig. 7F).

Platelet count at 7 days after surgery

The statistical outcome described that laparoscopic arm was mathematically comparable with open surgery concerning the platelet count at 7 days after surgery (n = 2, WMD: −12.65 × 109/l, 95 % CI −93.51 to 68.20, P = 0.76, I 2 = 58 %; Fig. 7G).

Total bilirubin level at 7 days after surgery

In contrast to open manipulation, the pooled data revealed that patients undergoing laparoscopic dissection were detected with lower total bilirubin level at 7 days after surgery (n = 2, WMD: −2.84 μmol/l, 95 % CI −5.20 to −0.49, P = 0.02, I 2 = 6 %; Fig. 7H).

ALT level at 7 days after surgery

It was implicated by the pooled analysis that laparoscopic technique resulted in lower ALT level at 7 days after surgery than open arm (n = 3, WMD: −5.94 IU/l, 95 % CI −10.07 to −1.81, P = 0.005, I 2 = 5 %; Fig. 7I).

AST level at 7 days after surgery

Our pooled outcome represented that the AST level at 7 days after surgery was significantly lower in laparoscopic group against that of open splenectomy (n = 3, WMD: −6.53 IU/l, 95 % CI −10.78 to −2.27, P = 0.003, I 2 = 0 %; Fig. 7J).

Heterogeneity adjustment and publication bias

The statistical heterogeneity across studies was adjusted properly by random-effects model to minimize the instability of the pooled outcomes. According to Cochrane Handbook, the analysis of publication bias was statistically credible in the setting of enough studies included. Hence, postoperative hospital stay in Section 1 with nine trials contained was selected as an end point to be assessed. As a consequence, the funnel plot is symmetrically demonstrated in Fig. 8, and the result of Egger’s test was not statistically significant (P = 0.18).

Discussion

Surgical removal of the morbid spleens has been gradually dominated by laparoscopic modality since its debut in early 1990s. Attributed to its intrinsic strengths, emerging literatures have hinted that laparoscopic splenectomy effectively functions in reducing physical trauma and improving postoperative rehabilitation, as well as enhancing cosmesis. In line with the clinical guideline of European Association for Endoscopic Surgery (EAES), laparoscopic dissection has been recognized as the preferred regimen for normal to moderately enlarged spleens however except for massive splenomegaly and severe portal hypertension along with hypersplenism [2].

Currently, a wide spectrum of splenic disorders is capable of being laparoscopically cured, including benign and malignant hematologic illnesses with spleen involvement. Taking idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura as an example, patients are forced to fall back on spleen surgeons in the case of medication refractoriness. Nevertheless, due to the causal bleeding tendency and long-term history of steroids administration, the conventional open surgery that features extensive traumas easily induces a higher possibility of surgical site infection and unfavorable postoperative recovery on surgical inpatients. With equivalent primary end points such as long-term remission rate, laparoscopic splenectomy overmatches open modality in terms of lower complication incidence as well as accelerated recovery course, which leads to the revolutionary alteration on gold standard technique of splenectomy [44]. However, despite its natural advantages and praises from professional societies, several major drawbacks have impeded its broader popularity. Firstly, a smooth disposal of the splenic hilum and ligation of splenic pedicle under laparoscope are of greater hazards, since the tortuous pedicle vessels are surrounded by intricate anatomical structures, which complicates the safely laparoscopic ligation. Secondly, an elongated learning curve is required in order to become experienced hands on laparoscopic splenectomy, which triggers a relatively prolonged surgical duration against that of open surgery [45]. Fortunately, along with the surgical innovation and accumulating experiences, those blockages seem to be successfully resolved at present. Sampath et al. [29] reported a convenient ligation of silk thread suspended splenic pedicle by an auto-suture device of Endo-GIA, which significantly reduced the surgical time as well as conversion rate due to massive hemorrhage. Likewise, Qu et al. [27] described a time-saving benefit from assisted small incision below left costal margin when coping with the splenic pedicle. This direct-viewing manipulation could remarkably enhance the surgical safety as well. Moreover, the higher sensitivity (93.3 %) and specificity (100 %) of laparoscopic detection of accessory spleen play an auxiliary role in preventing resurgence of thrombocytopenia, therapeutically and economically preceding the conventional preoperative CT assessment [46]. Therefore, our quantitative meta-analysis is in accordance with current progress and novel viewpoints that laparoscopic splenectomy is all-around superior to open surgery regarding idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura.

A typical contraindication of laparoscopic splenectomy is severe portal hypertension secondary to liver cirrhosis, especially of those accompanied with massive splenomegaly. On this occasion, hand-assisted laparoscopic treatment is preferably recommended instead [2]. A hand-port device technically facilitates and secures the management of highly varicose vessels within the splenic pedicle as well as the severe perisplenic adhesion, which endanger the surgical patients and probably culminates in uncontrollably massive hemorrhage under a total laparoscopic arm. Additionally, through the hand-assisted instrument, less effort is required to bring out the swollen spleen in an intact form without tissue implantation, which shortens the length of surgical duration and partially ameliorates the anesthetic strike on liver functionality. Nevertheless, the heavier hospitalization expenses and relatively enlarged trauma on patients overshadow the superiority of this technical hybrid, forcing surgeons to come back on total laparoscope. Similarly, a secure ligation of splenic pedicle is also the major concern to laparoscopically accomplish the dissection of spleens [47]. Conventionally, a branch-by-branch silk thread ligation largely contributes to the laparoscopic manipulation of pedicle vessels, which is a time-consuming event and easily leads to vascular lacerations. However, following the in-depth perspectives on regional anatomy, Wang et al. [48] discovered an avascular area above the splenic pedicle, which was constantly existed and proportional to spleen size. Without evident bleeding, a surgical tunnel of splenic pedicle could be readily constructed through this area. Hence, under this circumstance, it was more convenient and safe to cut apart the vessels by an auto-suture device of Endo-GIA. Besides, Kawanaka et al. [47] suggested that enhanced proficiency and tissue morcellator jointly contribute to the elevated safety and decreased surgical time, as well as maintaining the minimal invasiveness. Furthermore, on the other side, esophageal varicosity is a concomitant manifestation that commonly accompanies with portal hypertension. Rather than total laparoscope, a hand-assisted laparoscopic instrument frequently bothers the manipulation of pericardial devascularization especially under a narrow operation space with massive splenomegaly [49]. In agreement with these novel perspectives, our pooled outcomes identically explored compelling values of laparoscopic splenectomy toward patients suffering from portal hypertension, revealing its great potential in future application.

In spite of the comprehensiveness and rigorousness of our meta-analysis, there are still some limitations. Firstly, the majority of the included studies were observational trials, which may latently induce severe risk of bias despite decent assessment scores. Literatures of high-quality randomized controlled trials are urgently needed in order for a more persuasive conclusion in future updates. Secondly, owing to the lack of original data, end points of long-term efficacy were rarely assessed in our meta-analysis, which may partially decline the reliability of the results. For example, with regard to portal hypertension, the long-term incidence of recurrent varicosity is a vital indicator to appraise the surgical efficacy. Thus, we expect more long-term investigations to be published as supplements to the current literatures.

Taken together, in a variety of splenic disorders, laparoscopic splenectomy should be recommended as a gold standard modality on the basis of our comprehensive meta-analysis, due to its comparable efficacy and superior postoperative recovery.

References

Feldman LS (2011) Laparoscopic splenectomy: standardized approach. World J Surg 35(7):1487–1495. doi:10.1007/s00268-011-1059-x

Habermalz B, Sauerland S, Decker G, Delaitre B, Gigot JF, Leandros E, Lechner K, Rhodes M, Silecchia G, Szold A, Targarona E, Torelli P, Neugebauer E (2008) Laparoscopic splenectomy: the clinical practice guidelines of the european association for endoscopic surgery (EAES). Surg Endosc 22(4):821–848. doi:10.1007/s00464-007-9735-5

Patel AG, Parker JE, Wallwork B, Kau KB, Donaldson N, Rhodes MR, O’Rourke N, Nathanson L, Fielding G (2003) Massive splenomegaly is associated with significant morbidity after laparoscopic splenectomy. Ann Surg 238(2):235–240. doi:10.1097/01.sla.0000080826.97026.d8

Al-Mulhim AS (2012) Laparoscopic splenectomy for massive splenomegaly in benign hematological diseases. Surg Endosc 26(11):3186–3189. doi:10.1007/s00464-012-2314-4

Xu J, Zhao L, Wang Z, Zhai B, Liu C (2014) Single-incision laparoscopic splenectomy for massive splenomegaly combining gastroesophageal devascularization using conventional instruments. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 24(5):e183. doi:10.1097/SLE.0000000000000073

Hozo SP, Djulbegovic B, Hozo I (2005) Estimating the mean and variance from the median, range, and the size of a sample. BMC Med Res Methodol 5:13. doi:10.1186/1471-2288-5-13

Yong F, Chen W, Lan P, Youcheng Z (2014) Applications of laparoscopic technique in spleen surgery. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 18(12):1713–1716

Ahad S, Gonczy C, Advani V, Markwell S, Hassan I (2013) True benefit or selection bias: an analysis of laparoscopic versus open splenectomy from the ACS-NSQIP. Surg Endosc 27(6):1865–1871. doi:10.1007/s00464-012-2727-0

Bulus H, Mahmoud H, Altun H, Tas A, Karayalcin K (2013) Outcomes of laparoscopic versus open splenectomy. J Korean Surg Soc 84(1):38–42. doi:10.4174/jkss.2013.84.1.38

Oomen MW, Bakx R, van Minden M, van Rijn RR, Peters M, Heij HA (2013) Implementation of laparoscopic splenectomy in children and the incidence of portal vein thrombosis diagnosed by ultrasonography. J Pediatr Surg 48(11):2276–2280. doi:10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2013.03.078

Barbaros U, Dinccag A, Sumer A, Vecchio R, Rusello D, Randazzo V, Issever H, Avci C (2010) Prospective randomized comparison of clinical results between hand-assisted laparoscopic and open splenectomies. Surg Endosc 24(1):25–32. doi:10.1007/s00464-009-0528-x

Canda AE, Sucullu I, Ozsoy Y, Filiz AI, Kurt Y, Demirbas S, Inan I (2009) Hospital experience, body image, and cosmesis after laparoscopic or open splenectomy. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 19(6):479–483. doi:10.1097/SLE.0b013e3181c3ff24

Boddy AP, Mahon D, Rhodes M (2006) Does open surgery continue to have a role in elective splenectomy? Surg Endosc 20(7):1094–1098. doi:10.1007/s00464-005-0523-9

Ikeda M, Sekimoto M, Takiguchi S, Kubota M, Ikenaga M, Yamamoto H, Fujiwara Y, Ohue M, Yasuda T, Imamura H, Tatsuta M, Yano M, Furukawa H, Monden M (2005) High incidence of thrombosis of the portal venous system after laparoscopic splenectomy: a prospective study with contrast-enhanced CT scan. Ann Surg 241(2):208–216

Qureshi FG, Ergun O, Sandulache VC, Nadler EP, Ford HR, Hackam DJ, Kane TD (2005) Laparoscopic splenectomy in children. JSLS 9(4):389–392

Hamamci EO, Besim H, Bostanoglu S, Sonisik M, Korkmaz A (2002) Use of laparoscopic splenectomy in developing countries: analysis of cost and strategies for reducing cost. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 12(4):253–258. doi:10.1089/109264202760268023

Minkes RK, Lagzdins M, Langer JC (2000) Laparoscopic versus open splenectomy in children. J Pediatr Surg 35(5):699–701. doi:10.1053/jpsu.2000.6010

Kucuk C, Sozuer E, Ok E, Altuntas F, Yilmaz Z (2005) Laparoscopic versus open splenectomy in the management of benign and malign hematologic diseases: a ten-year single-center experience. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 15(2):135–139. doi:10.1089/lap.2005.15.135

Sapucahy MV, Faintuch J, Bresciani CJ, Bertevello PL, Habr-Gama A, Gama-Rodrigues JJ (2003) Laparoscopic versus open splenectomy in the management of hematologic diseases. Rev Hosp Clin Fac Med Sao Paulo 58(5):243–249

Velanovich V, Shurafa MS (2001) Clinical and quality of life outcomes of laparoscopic and open splenectomy for haematological diseases. Eur J Surg 167(1):23–28. doi:10.1080/110241501750069774

Donini A, Baccarani U, Terrosu G, Corno V, Ermacora A, Pasqualucci A, Bresadola F (1999) Laparoscopic vs open splenectomy in the management of hematologic diseases. Surg Endosc 13(12):1220–1225

Zhe C, Jian-wei L, Jian C, Yu-dong F, Ping B, Shu-guang W, Shu-guo Z (2013) Laparoscopic versus open splenectomy and esophagogastric devascularization for bleeding varices or severe hypersplenism: a comparative study. J Gastrointest Surg 17(4):654–659. doi:10.1007/s11605-013-2150-4

Swanson TW, Meneghetti AT, Sampath S, Connors JM, Panton ON (2011) Hand-assisted laparoscopic splenectomy versus open splenectomy for massive splenomegaly: 20-year experience at a Canadian centre. Can J Surg 54(3):189–193. doi:10.1503/cjs.044109

Zhou J, Wu Z, Cai Y, Wang Y, Peng B (2011) The feasibility and safety of laparoscopic splenectomy for massive splenomegaly: a comparative study. J Surg Res 171(1):e55–e60. doi:10.1016/j.jss.2011.06.040

Feldman LS, Demyttenaere SV, Polyhronopoulos GN, Fried GM (2008) Refining the selection criteria for laparoscopic versus open splenectomy for splenomegaly. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 18(1):13–19. doi:10.1089/lap.2007.0050

Owera A, Hamade AM, Bani HO, Ammori BJ (2006) Laparoscopic versus open splenectomy for massive splenomegaly: a comparative study. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 16(3):241–246. doi:10.1089/lap.2006.16.241

Qu Y, Xu J, Jiao C, Cheng Z, Ren S (2014) Long-term outcomes of laparoscopic splenectomy versus open splenectomy for idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. Int Surg 99(3):286–290. doi:10.9738/INTSURG-D-13-00175.1

Mohamed SY, Abdel-Nabi I, Inam A, Bakr M, El TK, Saleh AJ, Alzahrani H, Abdu SH (2010) Systemic thromboembolic complications after laparoscopic splenectomy for idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura in comparison to open surgery in the absence of anticoagulant prophylaxis. Hematol Oncol Stem Cell Ther 3(2):71–77

Sampath S, Meneghetti AT, MacFarlane JK, Nguyen NH, Benny WB, Panton ON (2007) An 18-year review of open and laparoscopic splenectomy for idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. Am J Surg 193(5):580–584. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2007.02.002

Ojima H, Kato T, Araki K, Okamura K, Manda R, Hirayama I, Hosouchi Y, Nishida Y, Kuwano H (2006) Factors predicting long-term responses to splenectomy in patients with idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. World J Surg 30(4):553–559. doi:10.1007/s00268-005-7964-0

Berends FJ, Schep N, Cuesta MA, Bonjer HJ, Kappers-Klunne MC, Huijgens P, Kazemier G (2004) Hematological long-term results of laparoscopic splenectomy for patients with idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura: a case control study. Surg Endosc 18(5):766–770. doi:10.1007/s00464-003-9140-7

Cordera F, Long KH, Nagorney DM, McMurtry EK, Schleck C, Ilstrup D, Donohue JH (2003) Open versus laparoscopic splenectomy for idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura: clinical and economic analysis. Surgery 134(1):45–52. doi:10.1067/msy.2003.204

Shimomatsuya T, Horiuchi T (1999) Laparoscopic splenectomy for treatment of patients with idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. Comparison with open splenectomy. Surg Endosc 13(6):563–566

Alwabari A, Parida L, Al-Salem AH (2009) Laparoscopic splenectomy and/or cholecystectomy for children with sickle cell disease. Pediatr Surg Int 25(5):417–421. doi:10.1007/s00383-009-2352-8

Lesher AP, Kalpatthi R, Glenn JB, Jackson SM, Hebra A (2009) Outcome of splenectomy in children younger than 4 years with sickle cell disease. J Pediatr Surg 44(6):1134–1138. doi:10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2009.02.016

Goers T, Panepinto J, Debaun M, Blinder M, Foglia R, Oldham KT, Field JJ (2008) Laparoscopic versus open abdominal surgery in children with sickle cell disease is associated with a shorter hospital stay. Pediatr Blood Cancer 50(3):603–606. doi:10.1002/pbc.21245

Bai DS, Qian JJ, Chen P, Yao J, Wang XD, Jin SJ, Jiang GQ (2014) Modified laparoscopic and open splenectomy and azygoportal disconnection for portal hypertension. Surg Endosc 28(1):257–264. doi:10.1007/s00464-013-3182-2

Jiang GQ, Chen P, Qian JJ, Yao J, Wang XD, Jin SJ, Bai DS (2014) Perioperative advantages of modified laparoscopic vs open splenectomy and azygoportal disconnection. World J Gastroenterol 20(27):9146–9153. doi:10.3748/wjg.v20.i27.9146

Wu Z, Zhou J, Pankaj P, Peng B (2012) Laparoscopic and open splenectomy for splenomegaly secondary to liver cirrhosis: an evaluation of immunity. Surg Endosc 26(12):3557–3564. doi:10.1007/s00464-012-2366-5

Zhou J, Wu Z, Pankaj P, Peng B (2012) Long-term postoperative outcomes of hypersplenism: laparoscopic versus open splenectomy secondary to liver cirrhosis. Surg Endosc 26(12):3391–3400. doi:10.1007/s00464-012-2349-6

Cai YQ, Zhou J, Chen XD, Wang YC, Wu Z, Peng B (2011) Laparoscopic splenectomy is an effective and safe intervention for hypersplenism secondary to liver cirrhosis. Surg Endosc 25(12):3791–3797. doi:10.1007/s00464-011-1790-2

Jiang XZ, Zhao SY, Luo H, Huang B, Wang CS, Chen L, Tao YJ (2009) Laparoscopic and open splenectomy and azygoportal disconnection for portal hypertension. World J Gastroenterol 15(27):3421–3425

Xin Z, Qingguang L, Yingmin Y (2009) Total laparoscopic versus open splenectomy and esophagogastric devascularization in the management of portal hypertension: a comparative study. Dig Surg 26(6):499–505. doi:10.1159/000236033

Rijcken E, Mees ST, Bisping G, Krueger K, Bruewer M, Senninger N, Mennigen R (2014) Laparoscopic splenectomy for medically refractory immune thrombocytopenia (ITP): a retrospective cohort study on longtime response predicting factors based on consensus criteria. Int J Surg 12(12):1428–1433. doi:10.1016/j.ijsu.2014.10.012

Montalvo J, Velazquez D, Pantoja JP, Sierra M, Lopez-Karpovitch X, Herrera MF (2014) Laparoscopic splenectomy for primary immune thrombocytopenia: clinical outcome and prognostic factors. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 24(7):466–470. doi:10.1089/lap.2013.0267

Gamme G, Birch DW, Karmali S (2013) Minimally invasive splenectomy: an update and review. Can J Surg 56(4):280–285

Kawanaka H, Akahoshi T, Kinjo N, Harimoto N, Itoh S, Tsutsumi N, Matsumoto Y, Yoshizumi T, Shirabe K, Maehara Y (2015) Laparoscopic splenectomy with technical standardization and selection criteria for standard or hand-assisted approach in 390 patients with liver cirrhosis and portal hypertension. J Am Coll Surg 221(2):354–366. doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2015.04.011

Wang WJ, Tang Y, Zhang Y, Chen Q (2015) Prevention and treatment of hemorrhage during laparoscopic splenectomy and devascularization for portal hypertension. J Huazhong Univ Sci Technolog Med Sci 35(1):99–104. doi:10.1007/s11596-015-1396-3

Jiang G, Qian J, Yao J, Wang X, Jin S, Bai D (2014) A new technique for laparoscopic splenectomy and azygoportal disconnection. Surg Innov 21(3):256–262. doi:10.1177/1553350613492587

Acknowledgments

We sincerely appreciate members in our research group for methodological assistance.

Funding

Our study was financially funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81372559) and Research Fund of Public Welfare in Health Industry, Health and Family Plan Committee of China (No. 201402015).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclosures

Ji Cheng, Kaixiong Tao, and Peiwu Yu declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

An erratum to this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00464-016-4949-z.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cheng, J., Tao, K. & Yu, P. Laparoscopic splenectomy is a better surgical approach for spleen-relevant disorders: a comprehensive meta-analysis based on 15-year literatures. Surg Endosc 30, 4575–4588 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-016-4795-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-016-4795-z