Abstract

Background

The relationship between volume and outcomes in bariatric surgery is well established in the literature. However, the analyses were performed primarily in the open surgery era and in the absence of national accreditation. The recent Metabolic Bariatric Surgery Accreditation and Quality Improvement Program proposed an annual threshold volume of 50 stapling cases. This study aimed to examine the effect of volume and accreditation on surgical outcomes for bariatric surgery in this laparoscopic era.

Methods

The Nationwide Inpatient Sample was used for analysis of the outcomes experienced by morbidly obese patients who underwent an elective laparoscopic stapling bariatric surgical procedure between 2006 and 2010. In this analysis, low-volume centers (LVC < 50 stapling cases/year) were compared with high-volume centers (HVC ≥ 50 stapling cases/year). Multivariate analysis was performed to examine risk-adjusted serious morbidity and in-hospital mortality between the LVCs and HVCs. Additionally, within the HVC group, risk-adjusted outcomes of accredited versus nonaccredited centers were examined.

Results

Between 2006 and 2010, 277,760 laparoscopic stapling bariatric procedures were performed, with 85 % of the cases managed at HVCs. The mean number of laparoscopic stapling cases managed per year was 17 ± 14 at LVCs and 144 ± 117 at HVCs. The in-hospital mortality was higher at LVCs (0.17 %) than at HVCs (0.07 %). Multivariate analysis showed that laparoscopic stapling procedures performed at LVCs had higher rates of mortality than those performed at HVCs [odds ratio (OR) 2.5; 95 % confidence interval (CI) 1.3–4.8; p < 0.01] as well as higher rates of serious morbidity (OR 1.2; 95 % CI 1.1–1.4; p < 0.01). The in-hospital mortality rate at nonaccredited HVCs was 0.22 % compared with 0.06 % at accredited HVCs. Multivariate analysis showed that nonaccredited centers had higher rates of mortality than accredited centers (OR 3.6; 95 % CI 1.5–8.3; p < 0.01) but lower rates of serious morbidity (OR 0.8; 95 % CI 0.7–0.9; p < 0.01).

Conclusion

In this era of laparoscopy, hospitals managing more than 50 laparoscopic stapling cases per year have improved outcomes. However, nonaccredited HVCs have outcomes similar to those of LVCs. Therefore, the impact of accreditation on outcomes may be greater than that of volume.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The outcomes after bariatric surgery have improved tremendously during the past decade with the national increase in the use of laparoscopic bariatric surgery and with the initiation of bariatric surgery accreditation in 2004 by the American Society of Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery (ASMBS) and in 2005 by the American College of Surgeons (ACS) [1, 2].

Currently, more than 90 % of elective bariatric surgical cases are managed worldwide using the laparoscopic approach [3]. With regard to bariatric surgery accreditation, the requisite criteria for a facility to be accredited include availability of appropriate equipment to care for the morbidly obese, an appropriately trained staff, experienced surgeons, a multidisciplinary team, and an annual hospital volume of 125 cases per year [4]. The annual volume requirement of 125 cases was based on data demonstrating a direct relationship between volume and improved mortality associated with bariatric surgery [5–10].

In April 2012, the ASMBS and the ACS initiated the Metabolic Bariatric Surgery Accreditation and Quality Improvement Program (MBSAQIP), a unified national bariatric surgery accreditation program. The standards for the new accreditation program were recently released for public comment.

The proposed standards are similar to previous standards except for a suggested change in the annual volume criteria and new implementation of a quality improvement standard. The newly proposed volume criterion for a comprehensive accredited center is 50 stapling cases per year.

Unlike the previous annual volume criterion of 125 cases per year, the newly proposed volume criterion is based on both volume (50 cases per year) and type of bariatric surgical cases (i.e., stapling cases). The previous annual volume threshold of 125 cases per year did not take into account the type of cases. Therefore, a center could be designated as an accredited center even if it managed minimal or no stapling bariatric cases (i.e., Roux-en-Y gastric bypass). Additionally, the 125-case threshold could be difficult to achieve by many smaller or rural centers, which could potentially result in reduced patient access to quality care [11–13].

The reason for including the type of surgical cases in the new MBSAQIP program was that the outcome–volume relationship in bariatric surgery has been observed only for stapling cases such as Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. No such relationship has been observed for gastric banding procedures [9].

Because most of the current volume and outcome data in bariatric surgery were derived from open surgical technique, this study aimed to analyze contemporary data (2006–2010) in this laparoscopic era after the institution of centers of excellence, to examine whether an association exists between volume and outcome based on the newly suggested MBSAQIP annual hospital threshold volume of 50 stapling cases per year, and to determine the impact of accreditation at centers managing a high volume of stapling cases.

Methods and procedures

The Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) database is the largest all-payer inpatient care database publicly available in the United States. It contains information on nearly 8 million hospital stays per year from 1,000 hospitals across the country.

The NIS data, compiled from hospital discharge abstracts, identifies all the procedures performed during a given hospital stay. The data set approximates a 20 % stratified sample of American community, nonmilitary, and nonfederal hospitals, resulting in a sampling frame that comprises approximately 95 % of all hospital discharges in the United States.

Data elements within the NIS, drawn from hospital discharge abstracts, allow determination of all procedures performed during a given hospital stay. Weighting strategies are used to produce national averages from sampled numbers.

Approval for the use of the NIS patient-level data in this study was obtained from the institutional review board of the University of California Irvine Medical Center and the NIS.

Using the NIS database, we examined elective admission of morbidly obese patients who underwent laparoscopic gastric stapling bariatric procedures between 1 January 2006 and 31 December 2010. These cases were identified using appropriate diagnosis and procedural codes as specified by the International Classification of Diseases, 9th Edition, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM). The principal ICD-9 codes for obesity and morbid obesity (278.0, 278.01, and 278.00) were used. These codes included a subcategory for obesity and a subclassification of morbid obesity.

The ICD-9 procedural codes for laparoscopic gastric stapling bariatric procedures included 44.38 for laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass as well as 43.82 and 44.68 for laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Patients who underwent emergent, open, or gastric banding procedures were excluded from the analysis.

We examined characteristics and outcome data of morbidly obese patients who underwent laparoscopic gastric stapling procedures at low- versus high-volume centers. Using the unique hospital identification number for each hospital, the annual number of laparoscopic stapling bariatric cases was calculated for each hospital. A low-volume center (LVC) was defined as a facility that managed fewer than 50 cases per year. A high-volume center (HVC) was a facility that managed 50 or more cases per year during each sampled year. A hospital could be designated as an HVC for 1 year but as an LVC for another year due to fluctuation in its annual case volume.

A subgroup analysis was performed among HVCs in which the characteristics and outcome data were compared between nonaccredited and accredited centers. Accredited centers were selected according to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) listing of bariatric surgery accreditation. Specific American hospital association codes within the NIS were determined to categorize centers into either nonaccredited or accredited centers.

The baseline characteristics included demographics (age, gender, and ethnicity), hospital characteristics, and comorbidities. The primary outcome measures were selected a priori and included the rates for serious morbidity and in hospital mortality. Serious morbidity included anastomotic leak, sepsis, pulmonary infections, acute respiratory failure, acute renal failure, cardiac complications, cerebrovascular accident, deep venous thrombosis, and wound complications. The secondary outcome measures included length of hospital stay, specific postoperative complications, and mean hospital charges.

The postoperative wound complications included ICD-9 codes for wound infection and dehiscence. The ICD-9 code for anastomotic leak included the code for anastomotic complication. The cardiac complications included myocardial infarction and heart failure. Acute renal failure included acute renal insufficiency.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.3 (SAS, Carey, NC, USA) and the R statistical environment. All analyses were performed with raw numbers weighted to reflect national averages. For comparison of LVCs and HVCs and of nonaccredited and accredited centers, inference was drawn using logistic regression for binary end points (in-hospital mortality and serious morbidity).

The independent variables used for risk adjustment included demographics (age, gender, and ethnicity), hospital characteristics (type and location), comorbidities (anemia, rheumatoid arthritis, congestive heart failure, chronic pulmonary disease, coagulopathy, diabetes, complicated and uncomplicated hypertension, hypothyroidism, peripheral vascular disorders, renal failure/insufficiency, and smoking), and procedural type (laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass vs sleeve gastrectomy).

Robust standard errors [14] were used for inference to guard against model misspecification, and Holm’s method [15] was used to account for multiple comparisons between adjusted p values. Comparisons were declared statistically significant with an error level of 0.05 if an adjusted p value was lower than 0.05.

Results

High- versus low-volume centers

Between 2006 and 2010, 277,760 elective laparoscopic stapling bariatric cases were managed. Of the 277,760 cases, 236,219 (85 %) were managed at HVCs (≥50 stapling cases/year) at a mean of 328 ± 48 centers per year, with each center managing a mean of 144 ± 117 cases per year. In contrast, 41,547 (15 %) of the 277,760 cases were performed at LVCs (<50 stapling cases per year) at a mean of 484 ± 50 centers per year, with each center performing a mean of 17 ± 14 cases per year (Table 1).

The majority of the patients in both groups underwent gastric bypass (94.7 % at LVCs vs 97.4 % at HVCs). In terms of accreditation, 90 % of HVCs were accredited centers compared with 55 % of LVCs. The mean age and proportion of women were similar in the two groups. The LVCs had a higher proportion of Caucasians. The HVCs had a significantly higher proportion of urban and teaching hospitals (Table 1).

Table 2 lists the comorbidities of the patients who underwent laparoscopic gastric stapling bariatric procedures at HVCs versus LVCs. Although the overall van Walraven/Elixhauser comorbidity score [16] was similar between the HVCs and LVCs, the HVCs had a higher rate of comorbidities including anemia, rheumatoid arthritis/collagen, congestive heart failure, chronic pulmonary disease, diabetes, hypertension, hypothyroidism, and renal failure.

The univariate analyses showed a higher in-hospital mortality rate for LVCs (0.17 %) than for HVCs (0.07 %) (p < 0.05) (Table 3). The overall in-hospital morbidity rate was higher at LVCs (6.72 %) than at HVCs (5.62 %) (p < 0.05). The incidences of anastomotic leak, sepsis, wound complications, ileus, and respiratory failure were higher at LVCs than at HVCs (p < 0.01). The HVCs had a shorter hospital stay (mean difference, −1 days) and lower hospital charges (mean difference, −$6,020) than the LVCs (Table 3).

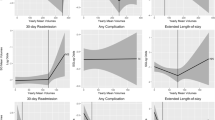

Table 7 lists the multivariate analysis comparisons of HVCs and LVCs. Compared with the HVCs, the LVCs were associated with higher rates of in-hospital mortality [odds ratio (OR), 2.5; p < 0.01] and serious morbidity (OR 1.2; p < 0.01).

Accredited and nonaccredited HVCs

A subset analysis of HVCs showed that 90 % were ASMBS- or ACS-accredited centers (mean 296 ± 49 centers/year), with each center managing a mean 149 ± 122 cases per year. In contrast, 10 % of HVCs were nonaccredited centers (mean, 40 ± 15 centers/year), with each center managing a mean of 106 ± 61 cases per year.

The majority of the patients in both groups underwent gastric bypass (89.3 % at nonaccredited centers vs 98.1 % at accredited centers). The mean age was similar in the two groups, but the proportion of women was higher at the accredited centers. The accredited group had a higher proportion of Caucasians as well as a significantly higher proportion of urban and teaching hospitals (Table 4).

Table 5 lists the comorbidities of the patients who underwent laparoscopic gastric stapling bariatric procedures at nonaccredited versus accredited centers. The overall van Walraven/Elixhauser comorbidity score [16] was similar in the two groups, but the accredited centers had a higher prevalence of congestive heart failure, chronic pulmonary disease, diabetes, hypertension, hypothyroidism, peripheral vascular disorders, and smoking.

According to the univariate analysis, in-hospital mortality was higher at the nonaccredited centers (0.22 %) than at the accredited centers (0.06 %) (p < 0.01) (Table 6). The overall in-hospital morbidity rate was lower at the nonaccredited centers (4.8 %) than at the accredited centers (5.7 %) (p < 0.05). The incidences of anastomotic leak, ileus, and urinary retention were lower at the nonaccredited centers than at the accredited centers (p < 0.01). The two groups had similar hospital stays and hospital charges (Table 6).

Table 7 lists the multivariate analyses of HVCs comparing the nonaccredited and accredited centers. Compared with the accredited centers, the nonaccredited centers were associated with higher rates of in-hospital mortality (OR 3.57; p < 0.01) and lower rates of serious morbidity (OR 0.84; p < 0.01).

Discussion

The published literature has clearly shown a volume–outcome relationship established for complex laparoscopic bariatric surgery [5–10]. Recently, the MBSAQIP proposed an annual threshold volume of 50 stapling cases per year.

Using the NIS, we examined the outcomes for LVCs (<50 cases per year) versus HVCs (≥50 cases per year) and found that HVCs were associated with lower risk-adjusted in-hospital mortality and serious morbidity. Additionally, 85 % of HVCs were accredited and 15 % were nonaccredited. Compared with the accredited centers, the nonaccredited centers were associated with higher risk-adjusted mortality rates but lower risk-adjusted serious morbidity rates.

The annual volume threshold in bariatric surgery is an important criterion for bariatric accreditation given its important association with improved outcomes [5–10]. The currently required annual hospital volume is 125 cases per year, but this number is not ideal, and MBSAQIP is proposing that this be changed to 50 or more stapling cases [6, 10, 17–19]. The reasons for this proposal is that the 125 cases threshold can be difficult to achieve by many centers, particularly centers in rural regions [11–13].

Additionally, the 125 annual case volume criterion does not take into account the type of surgical procedure. Furthermore, the volume–outcome relationship in bariatric surgery has been established only for complex cases such as Roux-en-Y gastric bypass [9].

Using the University Health System Consortium database, Nguyen et al. [6] analyzed 24,166 patients who underwent open Roux-en-Y gastric bypass at academic centers and found that centers performing fewer than 50 cases per year had the highest mortality rate: 1.2 versus 0.5 % for centers managing 50–100 cases annually and 0.5 % for centers managing more than 100 cases annually.

Based on the volume criteria recently proposed by MBSAQIP, we found that centers managing 50 or more laparoscopic stapling cases per year had lower rates for risk-adjusted in-hospital mortality and serious morbidity than centers managing fewer than 50 laparoscopic stapling cases per year. The data from the current study support improved outcome based on MBSAQIP’s newly proposed annual volume threshold of 50 stapling cases.

In addition to the volume–outcome relationship well established in bariatric surgery, recent studies have demonstrated that accreditation may be another important factor for improvement of outcome in bariatric surgery [20]. In a study of 35,284 patients who underwent bariatric surgery between 2007 and 2009, Nguyen et al. [21] found significantly lower in-hospital mortality at accredited centers (0.06 %) than at nonaccredited centers (0.21 %). Using the nationwide Medicare data to examine 47,030 patients who underwent bariatric surgery, Flum et al. [20] similarly reported lower rates for mortality, complications, and readmission after the 2006 Medicare bariatric national coverage determination.

In the current study, we analyzed a subset of patients at centers performing 50 or more stapling cases per year and found higher risk-adjusted in-hospital mortality rates but lower serious morbidity rates associated with nonaccredited centers compared with accredited centers. Our results suggest that nonaccredited centers have lower complication rates than accredited centers. However, patients experiencing complications at nonaccredited centers may be more likely to die of their complications. This may represent a concept previously described as “failure to rescue” [22].

The reasons for failure to rescue are unknown but may include delay in the diagnosis of a complication or suboptimal management of a complication. Additionally, the mortality rates between accredited and nonaccredited centers may differ significantly even though both groups manage relatively high volumes of laparoscopic stapling cases.

In high-volume nonaccredited centers, the in-hospital mortality rate was comparable with that for low-volume hospitals managing fewer than 50 stapling cases per year (0.22 vs 0.17 %, respectively). This finding may reflect the fact that accreditation in bariatric surgery with the requisite facility, equipment infrastructure, staff, and surgeon experience may be a more important factor than having a high annual threshold case volume [22].

Our results are in contrast to those reported by Dimick et al. [23], who compared bariatric surgery complications before and after implementation of the Medicare national coverage determination and found that the rates for complications and reoperation before and after the CMS policy did not differ significantly and suggested that Medicare should reconsider the policy. The study by Dimick et al. [23] was flawed by the use of non-Medicare patients as the control group, assuming that they were not exposed to the accreditation policy. This was not accurate because non-medicare patients actually were exposed to the accreditation process even earlier than Medicare patients (2006). Accreditation was established by the ASMBS in 2004 and by the ACS in 2005.

Study limitations

This study had several limitations. The NIS database, compiled from discharge abstract data, is limited to in-hospital morbidity and mortality without outpatient follow-up data such as postdischarge complications, readmissions, or long-term outcomes. Therefore, complications or deaths occurring after discharge are not captured in this database. The NIS also lacks important clinical information such as body mass index for risk adjustment, which is an important preoperative factor that can have an impact on outcome. Finally, coding for certain comorbidities and postoperative complications can be vague and subjectively defined compared with other objective variables such as length of hospital stay and in-hospital mortality. Despite these limitations, this study provided a large sample for evaluating the outcome of the proposed MBSAQIP annual threshold volume of 50 stapling cases per year and its impact on accreditation.

Conclusions

Using a national inpatient database, we examined the outcomes for patients with morbid obesity who underwent laparoscopic stapling bariatric procedures and found that centers with an annual hospital volume of 50 stapling cases per year had lower risk-adjusted morbidity and mortality rates than centers that managed fewer than 50 stapling cases per year. Relative to HVCs with accreditation, nonaccredited centers were associated with higher risk-adjusted mortality rates. Even high-volume nonaccredited centers that managed more than 50 cases per year had in-hospital mortality rates similar to those of LVCs. Our data therefore suggest that accreditation may have a greater impact on outcome than volume.

References

Flum DR, Salem L, Elrod JA, Dellinger EP, Cheadle A, Chan L (2005) Early mortality among medicare beneficiaries undergoing bariatric surgical procedures. JAMA 294:1903–1908

Pratt GM, McLees B, Pories WJ (2006) The ASBS Bariatric Surgery Centers of Excellence program: a blueprint for quality improvement. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2:497–503 discussion 503

Buchwald H, Oien DM (2013) Metabolic/bariatric surgery worldwide 2011. Obes Surg 23:427–436

American College of Surgeons. ACS BSCN accreditation program manual. Bariatric Surgery Centers Network, Chicago, IL. www.mbsaqip.org

Dimick JB, Osborne NH, Nicholas L, Birkmeyer JD (2009) Identifying high-quality bariatric surgery centers: hospital volume or risk-adjusted outcomes? J Am Coll Surg 209:702–706

Nguyen NT, Paya M, Stevens CM, Mavandadi S, Zainabadi K, Wilson SE (2004) The relationship between hospital volume and outcome in bariatric surgery at academic medical centers. Ann Surg 240:586–593 discussion 593–584

Markar SR, Penna M, Karthikesalingam A, Hashemi M (2012) The impact of hospital and surgeon volume on clinical outcome following bariatric surgery. Obes Surg 22:1126–1134

Gould JC, Kent KC, Wan Y, Rajamanickam V, Leverson G, Campos GM (2011) Perioperative safety and volume: outcomes relationships in bariatric surgery: a study of 32,000 patients. J Am Coll Surg 213:771–777

Zevin B, Aggarwal R, Grantcharov TP (2012) Volume–outcome association in bariatric surgery: a systematic review. Ann Surg 256:60–71

Campos GM, Ciovica R, Rogers SJ, Posselt AM, Vittinghoff E, Takata M, Cello JP (2007) Spectrum and risk factors of complications after gastric bypass. Arch Surg 142:969–975 discussion 976

Livingston EH, Elliott AC, Hynan LS, Engel E (2007) When policy meets statistics: the very real effect that questionable statistical analysis has on limiting health care access for bariatric surgery. Arch Surg 142:979–987

Livingston EH (2009) Bariatric surgery outcomes at designated centers of excellence vs nondesignated programs. Arch Surg 144:319–325 discussion 325

Livingston EH, Burchell I (2010) Reduced access to care resulting from centers of excellence initiatives in bariatric surgery. Arch Surg 145:993–997

Huber PJ (1967) The behavior of maximum likelihood estimates under nonstandard conditions. In Proceedings of the 5th Berkeley symposium on mathematical statistics and probability, Berkeley, CA

Holm S (1979) Proceedings of the fifth Berkeley symposium on mathematical statistics and probability. Scand J Stat 6:65–70

van Walraven C, Austin PC, Jennings A, Quan H, Forster AJ (2009) A modification of the Elixhauser comorbidity measures into a point system for hospital death using administrative data. Med Care 47:626–633

Parker M, Loewen M, Sullivan T, Yatco E, Cerabona T, Savino JA, Kaul A (2007) Predictors of outcome after obesity surgery in New York state from 1991 to 2003. Surg Endosc 21:1482–1486

Courcoulas A, Schuchert M, Gatti G, Luketich J (2003) The relationship of surgeon and hospital volume to outcome after gastric bypass surgery in Pennsylvania: a 3-year summary. Surgery 134:613–621 discussion 621–613

Liu JH, Zingmond D, Etzioni DA, O’Connell JB, Maggard MA, Livingston EH, Liu CD, Ko CY (2003) Characterizing the performance and outcomes of obesity surgery in California. Am Surg 69:823–828

Flum DR, Kwon S, MacLeod K, Wang B, Alfonso-Cristancho R, Garrison LP, Sullivan SD, Bariatric Obesity Outcome Modeling Collaborative (2011) The use, safety, and cost of bariatric surgery before and after medicare’s national coverage decision. Ann Surg 254:860–865

Nguyen NT, Nguyen B, Nguyen VQ, Ziogas A, Hohmann S, Stamos MJ (2012) Outcomes of bariatric surgery performed at accredited vs nonaccredited centers. J Am Coll Surg 215:467–474

Ghaferi AA, Birkmeyer JD, Dimick JB (2009) Complications, failure to rescue, and mortality with major inpatient surgery in medicare patients. Ann Surg 250:1029–1034

Dimick JB, Nicholas LH, Ryan AM, Thumma JR, Birkmeyer JD (2013) Bariatric surgery complications before vs after implementation of a national policy restricting coverage to centers of excellence. JAMA 309:792–799

Disclosures

Ninh T. Nguyen is the speaker bureau for Gore®. Mehraneh D. Jafari, Fariba Jafari, Monica T. Young, Brian R. Smith, and Michael J. Phalen have no conflicts of interest or financial ties to disclose.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jafari, M.D., Jafari, F., Young, M.T. et al. Volume and outcome relationship in bariatric surgery in the laparoscopic era. Surg Endosc 27, 4539–4546 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-013-3112-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-013-3112-3