Abstract

Tungiasis is a zoonosis neglected by authorities, health professionals, and affected populations. Domestic, synanthropic, and sylvatic animals serve as reservoirs for human infestation, and dogs are usually considered a main reservoir in endemic communities. To describe the seasonal variation and the persistence of tungiasis in dogs, we performed quarterly surveys during a period of 2 years in a tourist village in the municipality of Ilhéus, Bahia State, known to be endemic for tungiasis. Prevalence in dogs ranged from 62.1% (43/66) in August 2013 to 82.2% (37/45) in November 2014, with no significant difference (p = 0.06). The prevalence of infestation remained high, regardless of rainfall patterns. Of the 31 dogs inspected at all surveys, period prevalence was 94% (29/31; 95% CI 79.3–98.2%) and persistence of infestation indicator [PII] was high (median PII = 6 surveys, q1 = 5, q3 = 7). Dogs < 1 year of age had a higher mean prevalence of 84.5%, as compared with 69.3% in the older dogs. No significant difference was found between the risk of infestation and age or sex (p = 0.61). Our data indicate that canine tungiasis persisted in the area during all periods of the year. The seasonal variation described in human studies from other endemic areas was not observed, most probably due to different rainfall patterns throughout the year. The study has important implications for the planning of integrated control measures in both humans and animal reservoirs, considering a One Health approach.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The parasitic skin disease tungiasis (penetration of the female flea Tunga penetrans into the skin) causes considerable morbidity in human populations in endemic settings (Heukelbach et al. 2001, 2005; Feldmeier et al. 2014; Wiese et al. 2018). Animals are also commonly affected in endemic areas and have been considered to play a crucial role in transmission dynamics; tungiasis can thus be defined as a zoonotic disease (Heukelbach et al. 2002; Feldmeier et al. 2014; Mwangi et al. 2015; Wiese et al. 2017).

The animal host spectrum of T. penetrans includes a variety of mammals, including domestic, synanthropic, and sylvatic animals, and transmission cycles of humans and the different animal groups are overlapping (Heukelbach et al. 2001; Pilger et al. 2008; Feldmeier et al. 2014; Mwangi et al. 2015; Wiese et al. 2017). In endemic areas, dogs, cats, and pigs have been observed to be commonly infested (Heukelbach et al. 2004; Ugbomoiko et al. 2008a; Carvalho et al. 2012; Mutebi et al. 2016; Mwangi et al. 2015; Wiese et al. 2017). Several Brazilian studies evidenced high prevalences of infestation in dogs in resource-poor communities in Bahia (Harvey et al. 2017), Rio Grande do Norte (Bonfim et al. 2010), Ceará (Heukelbach et al. 2004), and Rio de Janeiro States (De Carvalho et al. 2003), where 62%, 47%, 67%, and 61% of dogs were infested, respectively. These studies indicated that dogs are one of the most important animal reservoirs in Brazil.

In Brazil, tungiasis is endemic in deprived urban areas, rural communities, and fishing villages throughout the country (Heukelbach et al. 2003; Carvalho et al. 2012), constituting, in some cases, a major public health problem (Heukelbach 2005). A study on the impact of socio-environmental factors on infestation showed that deficiency of sanitary infrastructure, low education level, inadequate hygiene habits, and the presence of dogs and cats inside houses and on the compound were associated with tungiasis (Muehlen et al. 2006). Recently, we have observed that a low level of supervision given to the dogs and the presence of sandy soil on the compound were significantly associated with canine tungiasis in a highly endemic setting (WHO 1990; Harvey et al. 2017). However, the few studies that included dogs focused on point prevalence (De Carvalho et al. 2003; Heukelbach et al. 2004; Pilger et al. 2008; Ugbomoiko et al. 2008a; Mutebi et al. 2015). Consequently, the transmission dynamics of Tunga in dogs have not been clarified yet. In this context, the investigation of the persistence of infestation in dogs throughout the year as well as its seasonal variation becomes fundamental for the assessment of transmission dynamics. This approach may favor the definition of more effective strategies for the prevention and control of the infestation in dogs and, consequently, in humans. We conducted a 2-year longitudinal study on the canine population diagnosed with tungiasis in an endemic area in Northeast Brazil.

Methods

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from dog owners for clinical examination, imaging, and administration of questionnaires.

Study area

The study was conducted in a rural tourism community called Juerana, originally a fishing village in the northeast of Ilhéus, Bahia State (Soub 2013). The study area has been described in detail previously (Harvey et al. 2017). Briefly, the village is located in the tourist corridor of the Cocoa Coast, about 640 m inland from the Atlantic Ocean. The average annual temperatures of the municipality vary between 22 and 25 °C. The pluviometric regime is regular, with abundant rainfalls distributed throughout the year (BRAZIL/MAPA/CEPLAC/CEPEC 2003).

There are 104 households with a human population of approximately 370 inhabitants, mostly living in low socioeconomic conditions. The houses have a maximum of two floors, made of masonry, mud, wood, and recyclable material; there are also several unfinished masonry houses. The study area is comparable to several other rural communities in northeastern Brazil.

At baseline of the study, the overall dog population of 114 corresponded to 30.9% of the human population, with a human:dog ratio of 3.2:1; 83.3% of them were semi-restricted (Harvey et al. 2017).

Study population and design

This longitudinal study was performed from August 2013 to May 2015. In the area, tungiasis is endemic with a prevalence of 62.3% in dogs. The target population consisted of the 114 examined dogs in a baseline survey (Harvey et al. 2017). The dogs were inspected every 3 months for the presence of lesions caused by Tunga, totaling eight quarterly surveys. Data of the baseline study have been published elsewhere in detail (Harvey et al. 2017). Only 17 owners allowed their dogs to be re-examined at all follow-up examinations. Consequently, of the 114 dogs in the baseline study, only 31 were covered in all surveys. The occurrence of tungiasis was assessed in the different seasons of the year, covering the periods of higher and lower rainfalls. Precipitation data for Ilhéus from 2005 to 2015 were obtained from the Environmental Resources Secretariat, of the Cocoa Research Center—BRAZIL/MAPA/CEPLAC/CEPEC/SERAM Climatology.

Clinical examination

Dogs, regardless of gender and age, were inspected after authorization from the owner. The animals were restrained mechanically and the entire body surface was thoroughly examined for the presence of lesions caused by Tunga fleas. The diagnosis of tungiasis was made by clinical inspection of the lesions, classified as vital and avital according to the Fortaleza Classification (Eisele et al. 2003). Lesions manipulated by the dog or owner were also recorded. Vital lesions correspond to stages I, II, and III of the infestation, while the avital lesions, considered dead, correspond to stages IV and V. Manipulated lesion is one in which the owner or dog breaks the bag and removes the eggs from the flea, resulting in a crater-like sore in the skin. The locations of lesions were noted, as well as dermatological and behavioral changes observed and reported by the owners.

Data analysis

Data were compiled, checked for entry-related errors, and analyzed using Epi Info™ software (version 7.2.0.1—Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, USA) and SPSS (version 20.0—IBM). Persistence of infestation indicator (PII) was used to measure the continuity of infestations during surveys of the 31 dogs that were followed up in all surveys. The surveys in which the animal was positive were added regardless of whether infestations were continuous or intermittent. In this way, the PII can vary from zero (negative dog in all surveys) to eight (positive dog in all surveys). Continuous PII suggest chronic infestations over months, as well as intermittent infestations suggest re-infestations. The number of dogs that continued being infested continued and the number of dogs that had periods without infestation followed by reinfestation was noted. Due to the small population size, we present the prevalences with their 95% confidence intervals calculated by the Wilson’s method (Wilson Score Interval). Age was divided into two age groups (dogs older than 1 year of age and dogs less than 1 year of age).

Due to discomfort and aggressive reactions manifested by the animals during the handling of the legs, the count of injuries was classified into less than and more than 10 lesions per type of injury, without counting in detail higher numbers of lesions. Normality was tested using the Shapiro-Wilk Test. Association between all exposure variables analyzed in the baseline study and PII were tested by the chi-square test and mean difference in persistence of infestation by Student’s t test.

Results

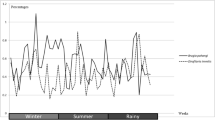

Table 1 presents prevalences by survey, demonstrating that the vast majority of animals had infestations over the assessed period. Point prevalences ranged from 62% in August 2013 to 82% in November 2014, with no significant difference (p = 0.06) (Table 1). The prevalence of infestation remained high, regardless of precipitation throughout the year (Fig. 1).

After the second survey, several factors led to losses of follow-up, such as the absence of dog owners on the days of visits, the death of several dogs during an outbreak of parvovirus infection and canine distemper, other causes of death at the study site, and migration to other households. Consequently, of the 114 dogs inspected in the first survey, only 31 (27.2%) were inspected at all surveys, and calculation of period prevalence and PII was based on this subpopulation. The period prevalence of tungiasis in this subpopulation was 94% (29/31; 95% CI 79.3–98.2%). Only 2 dogs remained without infestation during the eight surveys (21 months), both under the care of one guardian. There was a high persistence of infestation (median PII = 6 surveys, q1 = 5, q3 = 7). Of the 31 dogs, 81% were infested in five or more of the eight quarterly surveys performed, and 64.5% were infested in five to seven surveys. Eighteen (58%) were infested at five or more continuous surveys. This means, that these dogs remained infested for at least 18 months. Re-infestations were observed in 15 (48.1%) dogs (Table 2, Fig. 2). No significant association of age and sex with PII was found.

In dogs < 1 year of age, we observed a higher period prevalence and a higher mean prevalence of 83.3% (Table 3). There was no significant difference in the occurrence of cases by age (83.3% < 1 year of age/69.3% > 1 year of age; p = 0.76) (Table 3) or sex (males 95%; females 92%; p = 0.61) in this sample (Table 4).

On average, in this period, 72.2% of the dogs had vital lesions, 43.6% had avital lesions, and 63.7% had lesions manipulated. A total of 80.6% (n = 25) of the dogs presented with more than 10 vital lesions, 67.7% (n = 21) with more than 10 avital lesions, and 87.1% (n = 27) with more than 10 manipulated lesions (Fig. 3).

a Inspection of the dog with the help of the dog owner. b Embedded sand fleas (vital lesions) in the digital pad of a semi-restricted dog (arrow). c Manipulated lesions in the digital pad of a restricted dog (arrow). d Secondary myiasis in pad injured by Tunga ssp. (arrow). e Vital lesion in nose pad of a restricted dog. f Vital lesion in scrotal sac of a semi-restricted dog (arrow). Source—Tatiani V. Harvey

Discussion

Our study has shown that tungiasis infestation in dogs remained high throughout the year in a typical endemic setting, and that there was no seasonal pattern of infestation in these animals. This pattern contrasts directly with the seasonal variation observed in an endemic favela in Fortaleza in Ceará State, also located in the Northeast of Brazil (Heukelbach et al. 2005). This previous study showed a higher prevalence during the peak of the dry season peak. We observed that both communities had a similar socioeconomic and health profile, both were located near beach areas, and both had large number of dogs roaming on the streets. In Ceará State, rainfall is concentrated to one season. Therefore, the discrepancy between the two results can be explained by differences between the local climates and the distribution of rainfall during the year.

The dry season favors the biological cycle of Tunga, resulting in higher prevalences (Acha and Szyfres 2003). In contrast, a regular rainfall index could result in low prevalences, due to the maintenance of soil humidity, constantly interrupting the biological cycle of the parasite (Heukelbach et al. 2005). However, in our study area, it should be considered that rain usually occurs during a few hours of the day, damping only a superficial layer of the soil, which dries rapidly during sun exposure, which apparently does not have an impact on the life cycle of this arthropod.

The accuracy of time series analysis is favored by longer periods of study, which detect more reliable patterns of the behavior of a variable (Antunes and Cardoso 2015). In this case, the previously observed pattern may have been due to a year with unusual rainfalls. In the municipality of Ilhéus, a rainfall index over the past 10 years has shown a regular pattern in the distribution of rainfall (BRAZIL/MAPA/CEPLAC/CEPEC/SERAM 2016).

Considering the difference between the study populations, Heukelbach et al. (2005) hypothesized that the high prevalence rates in humans during the dry season could be explained by more intensive exposure to infested environments. In our study, the transmission dynamics are different. Due to their semi-restricted condition, animals were constantly exposed to infested areas, regardless of the season. Thus, for a population of semi-restricted dogs from endemic areas where there is a regular distribution of rainfall, tungiasis persisted, with prevalence rates that tend to be high throughout the year due to the increased risk of exposure to Tunga.

The major limitation of our study was the lack of data on human infestation, which would allow a broader view on the impact of tungiasis on quality of life of residents, as well as on the tourist population visiting the community. Moreover, the relatively low number of animals that could be inspected throughout the surveys may limit the interpretation of longitudinal data. Also, possibly, the 21-month evaluation period may also have been too short to demonstrate a more accurate seasonal pattern, as commented above.

In rural communities such as Vila Juerana, the circulation of synanthropic and wild animals such as rodents, foxes, and marmosets should also be considered, contributing to the perpetuation of Tunga in the environment (Heukelbach et al. 2004; Ugbomoiko et al. 2008a, b; Mwangi et al. 2015; Mutebi et al. 2018).

In the given setting, we understand that the persistence of infestation in dogs, with high prevalence rates, results fundamentally from human cultural behavior and habits. Among the main factors favoring this situation are the large number of semi-restricted dogs, inadequate management of the canine population, lack of knowledge about the treatment and control of the infestation, and other social determinants that directly affect the hygienic behavior of these individuals. Tungiasis is also neglected by both affected populations and health authorities (Heukelbach 2005; Harvey et al. 2017). Another important aspect of Tunga’s maintenance in the environment is the increased availability of shallow sandy soils characteristic of tropical coastal areas (Heukelbach 2005).

The importance of awareness about the prevention and control of tungiasis was demonstrated anecdotally by the follow-up of the two dogs that were not infested throughout the surveys. These were kept exclusively indoors. On the other hand, dogs that remained infested throughout the period belonged to owners who kept the animals loose and did not perceive tungiasis as a disease and therefore had no concern about treating the animal or removing the parasites. Dogs with intermittent infestations may represent two situations: (a) dog owners removed parasites, but no environmental control was performed, and the animal was likely to be reinfested; (b) the dogs themselves removed the parasites and the owners behaved in the same way as the owners of the dogs that presented continuous infestations, in other words, they did not treat the dogs. The perception of dog owners about the disease and about the care and responsibility with the animals influences the environment and treatment, and the situation of tungiasis in their animals. The large proportion of manipulated lesions demonstrated the neglect of the dog owners in the treatment and control of parasites in their animals.

The higher prevalence of the disease in male dogs may be due to the fact that dog owners often sequester females during heat. Due to the small sample size, this difference was not significant. Likewise, the highest prevalence in dogs younger than 1 year of age may be explained by contamination of the peri-domiciliary area and/or lack of ability to manage the infestation.

In this context, the analysis of the persistence of infestation has proven to be an important tool for description of the epidemiology of canine tungiasis, compared with the investigation of the point prevalence survey carried out in our baseline study (Harvey et al. 2017). The previous study emphasized the importance of the establishment of the disease in this population, while the longitudinal monitoring allowed a more accurate understanding of the ecology and the transmission dynamics of Tunga, facilitating the elaboration of more precise prevention and control strategies. Thus, these findings have important implications for disease control programs in Juerana, and in communities with similar characteristics, including tourist areas (Heukelbach et al. 2007; Gaines et al. 2014; Wilson et al. 2014), since the high prevalence.

The regularity of chronic and intermittent infestations indicates the need to implement continuous health education programs, in addition to the population control programs of dogs in this community. In this sense, only integrated and multidisciplinary control measures instituted by veterinarians, entomologists, sociologists, social workers, and physicians will lead to a sustainable control of the endemic situation.

Conclusions

The absence of a seasonal pattern and the persistence of high prevalence rates in dogs from a tropical endemic area demonstrate the need to implement continuous tungiasis prevention and control programs throughout the year. Sanitary deficiencies and semi-restricted dogs keep the environment infested and demonstrate the population’s neglect with the disease, since most of the animals in the study remained for long periods without effective treatment. The low level of education of the owners hampers prevention of this disease and provision of adequate treatment for the dogs. The predominance in the cohort of dogs with low level of restriction confirms the high risk of tungiasis in this population.

Programs based on a One Health strategy are essential to control tungiasis in communities with similar characteristics. In this way, endemic tourist sites such as the Village of Juerana should be included in these programs, as well as actions aimed at the adequate control of the canine population, in order to avoid the spread of tungiasis into non-infested areas. Effective control of the disease also depends to a large extent on governmental actions promoting the improvement of infrastructure and better health education programs focused on prophylactic measures.

References

Acha PN, Szyfres B (2003) Zoonosis y enfermedades transmisibles comunes a el hombre y a los animals. 3rd edn. Organización Panamericana de la Salud, Washington DC. 3 vols. (Publicación Científica y Técnica No. 580), 3:380–382

Antunes JLP, Cardoso MRA (2015) Uso da análise de séries temporais em estudos epidemiológicos. Epidemiol Serv Saude 4:565–576

Bonfim WM, Cardoso MD, Cardoso VA, Andreazze R (2010) Tungíase em uma área de aglomerado subnormal de Natal-RN: prevalência e fatores associados. Epidemiol Serv Saúde 19:379–388

BRAZIL/MAPA/CEPLAC (2003) Centro de Pesquisas do Cacau-Climatologia. Boletim Técnico 187

BRAZIL/MAPA/CEPLAC/CEPEC/SERAM (2016) Centero de Pesquisas do Cacau.Climatologia

Carvalho TF, Ariza L, Heukelbach J, Siva JJ, Mendes J, Silva AA, Limongi JE (2012) Conhecimento dos profissionais de saúde sobre a situação da tungíase em uma área endêmica no município de Uberlândia, Minas Gerais, Brasil, 2010. Epidemiol Serv Saúde 21:243–251

De Carvalho RW, De Almeida AB, Barbosa-Silva SC, Amorim M, Ribeiro PC, Serra-Freire NM (2003) The patterns of tungiasis in Araruama township, state of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 98:31–36

Eisele M, Heukelbach J, Van Marck E, Mehlhorn H, Meckes O, Franck S, Feldmeier H (2003) Investigations on the biology, epidemiology, pathology and control of Tunga penetrans in Brazil: I. Natural history of tungiasis in man. Parasitol Res 90:87–99

Feldmeier H, Heukelbach J, Ugbomoiko US, Sentongo E, Mbabazi P, von Samson-Himmelstjrna G, Krantz I (2014) Tungiasis—a neglected disease with many challenges for global public health. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 8:e3133

Gaines J, Sotir MJ, Cunningham TJ, Harvey KA, Lee CV, Stoney RJ, Gershman MD, Brunette GW, Kozarsky PE (2014) Health and safety issues for travelers attending the World Cup and Summer Olympic and Paralympic Games in Brazil, 2014 to 2016. JAMA Intern Med 174:1383–1390

Harvey TV, Heukelbach J, Assunção MS, Fernandes TM, Rocha CMBM, Carlos RSA (2017) Canine tungiasis: high prevalence in a tourist region in Bahia State, Brazil. Prev Vet Med 139:76–81

Heukelbach J (2005) Tungiasis. Rev Inst Med Trop 47:307–313

Heukelbach J, De Oliveira FA, Hesse G, Feldmeier H (2001) Tungiasis: a neglected health problem of poor communities. Tropical Med Int Health 6:267–272

Heukelbach J, Mencke N, Feldmeier H (2002) Cutaneous larva migrans and tungiasis: the challenge to control zoonotic ectoparasitoses associated with poverty. Tropical Med Int Health 7:907–910

Heukelbach J, Oliveira FAS, Feldmeier H (2003) Ectoparasitoses e saúde pública no Brasil:desafios para controle. Cad Saúde Pública 19:1535–1540

Heukelbach J, Costa AM, Wilcke T, Mencke N, Feldmeir H (2004) The animal reservoir of Tunga penetrans in severely affected communities of North-east Brazil. Med Vet Entomol 18:329–335

Heukelbach J, Wilcke T, Harms SG, Feldmeir H (2005) Seasonal variation of tungiasis in an endemic community. Am J Trop Med Hyg 72:145–149

Heukelbach J, Gomide M, Araújo Júnior F, Pinto NSR, Santana RD, Brito JRM, Feldmeier H (2007) Cutaneous larva migrans and tungiasis in international travelers exiting Brazil: an airport survey. J Travel Med 14:374–380

Muehlen M, Feldmeier H, Wilcke T, Winter B, Heukelbach J (2006) Identifying risk factors for tungiasis and heavy infestation in a resource-poor community in Northeast Brazil. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 100:371–380

Mutebi F, Krucken J, Feldmeier H, Waiswa C, Mencke N, Sentongo E, von Samson-Himmelstjerna G (2015) Animal reservoirs of zoonotic tungiasis in endemic rural villages of Uganda. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 9:e0004126

Mutebi F, Krücken J, Feldmeier H, Waiswa C, Mencke N, von Samson-Himmelstjerna G (2016) Tungiasis-associated morbidity in pigs and dogs in endemic villages of Uganda. Parasit Vectors 9:44

Mutebi F, Krücken J, von Samson-Himmelstjerna G, Waiswa C, Mencke N, Eneku W, Andrew T, Feldmeier H (2018) Animal and human tungiasis-related knowledge and treatment practices among animal keeping households in Bugiri District, south-eastern Uganda. Acta Trop 177:81–88

Mwangi JN, Ozwara HS, Gicheru MM (2015) Epidemiology of tunga penetrans infestation in selected areas in Kiharu constituency, Murang’a County, Kenya. Trop Dis Travel Med Vaccines 1:13

Pilger D, Schwalfenberg S, Heukelbach J, Witt L, Mehlhorn H, Mencke N, Khakban A, Feldmeier H (2008) Investigations on the biology, epidemiology, pathology, and control of Tunga penetrans in Brazil: VII. The importance of animal reservoirs for human infestation. Parasitol Res 102:875–880

Soub JNP (2013) Minha Ilhéus: fotografias do século XX e um pouco de nossa história. Editora Via Litterarum, Itabuna

Ugbomoiko US, Ariza L, Heukelbach J (2008a) Parasites of importance for human health in Nigerian dogs: high prevalence and limited knowledge of pet owners. BMC Vet Res 4:49

Ugbomoiko US, Ariza L, Heukelbach J (2008b) Pigs are the most important animal reservoir for Tunga penetrans (jigger flea) in rural Nigeria. Trop Dr 38:226–227

Wiese S, Elson L, Reichert F, Mambo B, Feldmeier H (2017) Prevalence, intensity and risk factors of tungiasis in Kilifi County, Kenya: I. Results from a community-based study. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 11(10):e0005925

Wiese S, Elson L, Feldmeier H (2018) Tungiasis-related life quality impairment in children living in rural Kenya. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 12(1):e0005939

Wilson ME, Chen LH, Han PV, Keystone JS, Cramer JP, Segurado A, Hale D, Jensenius M, Schwartz E, von Sonnenburg F, Leder K, for the GeoSentinel Surveillance Network, Plier A, Smith K, Burchard GD, Anand R, Gelman SS, Kain K, Boggild A, Perret C, Valdivieso F, Loutan L, Chappuis F, Schlagenhauf P, Weber R, Steffen R, Caumes E, Perignon A, Libman MD, Ward B, Maclean JD, Grobusch MC, Goorhuis A, de Vries P, Gadroen K, Mockenhaupt F, Harms G, Parola P, Simon F, Delmont J, Nord H, Laveran H, Carosi G, Castelli F, Connor BA, Kozarsky PE, Wu H, Fairley J, Franco-Paredes C, Using J, Froberg G, Askling HH, Bronner U, Haulman NJ, Roesel D, Jong EC, Lopez-Velez R, Perez Molina JA, Torresi J, Brown G, Licitra C, Crespo A, McCarthy A, Field V, Cahill JD, McKinley G, van Genderen PJ, Gkrania-Klotsas E, Stauffer WM, Walker PF, Kanagawa S, Kato Y, Mizunno Y, Shaw M, Hern A, Vincelette J, Freedman DO, Anderson S, Hynes N, Sack RB, McKenzie R, Nutman TB, Klion AD, Rapp C, Aoun O, Doyle P, Ghesquiere W, Valdez LM, Siu H, Tachikawa N, Kurai H, Sagara H, Lalloo DG, Beeching NJ, Gurtman A, McLellan S, Barnett ED, Hagmann S, Henry M, Miller AO, Mendelson M, Vincent P, Lynch MW, Hoang Phu PT, Anderson N, Batchelor T, Meisch D, Yates J, Ansdell V, Permanente K, Pandey P, Pradhan R, Murphy H, Basto F, Abreu C (2014) Illness in travelers returned from Brazil: the GeoSentinel experience and implications for the 2014 FIFA World Cup and the 2016 Summer Olympics. Clin Infect Dis 58:1347–1356

World Health Organization (1990) Guidelines for dog population management. https://www.paho.org/hq/dmdocuments/2009/nds-epi-profiles-final-sst-24-set.pdf. Accessed 1 June 2018

Acknowledgments

We thank Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado da Bahia—FAPESB (Bahia State Research Support Foundation) and the State University of Santa Cruz (UESC) for granting scholarships. We would like to thank Ford Harvey and Donald Pfarrer for help with the English version of this paper. Jorg Heukelbach (class 1) and Christiane M. B. M da Rocha (class 2) are research fellows from the Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

All procedures performed in studies involving animals were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institution or practice at which the studies were conducted. The study was approved by the Ethical Review Board for Animals of the State University of Santa Cruz (protocol number 06/2013).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Section Editor: Boris R. Krasnov

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Harvey, T.V., Heukelbach, J., Assunção, M.S. et al. Seasonal variation and persistence of tungiasis infestation in dogs in an endemic community, Bahia State (Brazil): longitudinal study. Parasitol Res 118, 1711–1718 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00436-019-06314-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00436-019-06314-w