Abstract

Objective

To establish more effective diagnostic procedures to identify the characteristic features of abdominopelvic tuberculosis (APTB) mimicking advanced ovarian cancer.

Methods

A retrospective review of 20 cases of APTB mimicking advanced ovarian cancer was undertaken.

Results

The mean age of the patients was 28.9 ± 10.8 years. The main clinical manifestations were abdominal pain (45%) and distention (45%). CA125 level was elevated in 18 cases (90.0%). Pelvic mass in 18 patients (90.0%) and ascites in 12 patients (60.0%) were detected by using abdominal US. The bacteriologic cultures and cytological studies were all negative (10 cases, 100%). Laparotomy (17 cases) and laparoscopic evaluation (1 case) was performed with the presumptive diagnosis of advanced ovarian cancer except for 2 patients treated with diagnostic anti-TB chemotherapy. The common intra-operative findings were miliary nodules (14 cases, 77.8%) and widespread adhesion (10 cases, 55.6%). Intra-operative frozen section was obtained in 10 cases, and the typical tuberculosis tubercles were detected in all cases.

Conclusion

APTB should be considered in all cases with pelvic mass, ascites and high levels of CA125, although clinical features and laboratory results specifically indicate neither ovarian malignancy nor APTB. Diagnostic laparotomy is a direct and safe method. To avoid extended surgery, the cases with APTB can be diagnosed through intra-operative frozen section in conjunction with clinical features.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Abdominopelvic tuberculosis (APTB) involved in the gastrointestinal tract, liver and female genital tract constitutes up to 1–3% of the total (Sheer and Coyle 2003). Patients with ascites, abdominopelvic masses and elevated serum CA125 levels are always easily misdiagnosed as ovarian malignancy. APTB requires conservative managements with anti-tuberculosis chemotherapy while ovarian malignancy requires extended surgery, chemotherapy, even with radiotherapy. However, increased serum CA125 levels, pelvic examination and abdominal ultrasonography (US)/CT are limited useful for screening. None of these methods has adequate sensitivity and specificity for confirming the diagnosis of APTB (Karlan and Platt 1995). Diagnosis is often delayed. In advanced stages, the surgery is required for the precise diagnosis in the most cases. This may result not only in unnecessary extended surgery but also in the loss of female genital organs.

APTB is uncommon in the industrialized countries today (Groutz et al. 1998; Piura et al. 2003; Miranda et al. 1996; Nistal de Paz et al. 1996; Sheth 1996). In this paper, 20 cases with a diagnostic dilemma of the preoperative differential diagnosis between APTB and the advanced ovarian cancer were analyzed. The aim of this retrospective study is to establish more effective diagnostic procedures to identify the characteristic features of APTB, which may be contribute to the differential diagnosis.

Methods

Twenty patients with a diagnostic dilemma of the suspected advanced ovarian cancer were diagnosed as APTB from January 1996 to December 2005 at the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology in Tongji hospital, TongJi Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, China. These patients diagnosed as APTB were recruited for this retrospective review.

Patients demographic, clinical features associated with medical illnesses, family and past history of TB were evaluated. The data about pure protein derived (PPD) status, gastrointestinal system (GIS) evaluation, routine biochemical tests, serum hemoglobin, CA125 and other preoperative tumor markers, acid-fast bacilli (AFB) staining and culture, ascetic fluid analysis, chest X-ray and abdominal US/CT results, as well as operative findings and histo-pathologic results, were performed.

Results

The mean age of the patients was 28.9 ± 10.8 years (median 27.5; range: 14–48), and the mean duration of symptoms was 14.5 ± 8.2 weeks (range: 1–96). The main clinical manifestations were abdominal pain (45%) and distention (45%). Abdominal mass was palpable in 7 cases (35%). Weight loss was shown to be present in 8 cases (40%), while 6 (20%) showed subfebrile fever (Table 1).

Three patients had past tuberculosis history in which two had pulmonary TB and one had tubercular pleurisy. One case had positive family history of TB.

Laboratory test

The tumor markers including CA125, AFP and CEA were detected here for differential diagnosis. In our series, the cancer antigen CA125 level was detected in all patients and elevated in 18 cases (90.0%). The average CA125 level was 286.37 ± 211.38 U/ml (range 10.21–706.80U/ml), while the levels of AFP were elevated in 11 of 16 cases (68.75%), and the average AFP was 6.28 ± 5.64 ng/mL. Moreover, the CEA levels in 11 of 18 cases (61.11%) and the average CEA 5.81 ± 6.30 ng/mL (Table 2).

Seventeen patients had slight or moderate anemia (85.0%), and the accelerations in the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) were detected in 5 of 6 cases (83.3%). The average hemoglobin was 101.2 ± 12.57 g/dL, and the average ESR was 57.2 ± 16.99 mm/h. PPD detection was performed in only 3 cases with strongly positive results.

Abdominal US and imaging results

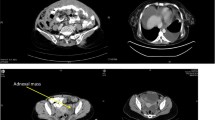

In all the patients, pelvic mass in 18 patients (90%) and ascites in 12 patients (60%) were detected by using abdominal US, and the average longest diameter was 7.29 ± 3.39 cm. The bilateral ovarian mass in 7 cases (38.9%) and the unilateral ovarian mass in 11 patients (61.1%) were found. The cystic mass was shown to be present in 7 cases (38.9%), while 3 showed solid mass (16.7%), 8 complex mass (44.4%) (Table 2).

Gastrointestinal system (GIS) examination was carried out on 12 patients, including colon barium air radiography (CBAR) in 6 case, 4 cases of intestinal barium (IB), 3 barium enema (BE), 2 upper digestive tract barium (UDTB), 1 colonoscopy (Col) and 1 Gastroscopy (Gas). The abnormal findings of pelvic disease were noted in 3 cases, and the results were shown in Table 2. Chest X-ray was carried out on all patients in which 6 patients (30%) were abnormal.

Operation and pathological examination

Abdominal paracentesis was preoperatively performed in 10 cases. The straw-colored exudative fluid with benign lymphocytes was discovered in each case; however, bacteriologic cultures and cytological studies of the ascitic fluid specimens were negative in all cases.

In our series, the temperature became normal, and the abdominal swelling was reduced in 2 cases after the diagnostic anti-TB chemotherapy. The suspicion of ovary malignancy leads to the operations in 18 cases.

Laparotomy was performed with the presumptive diagnosis of advanced ovarian cancer in 17 cases (85%) except for laparoscopic evaluation in one person. At the time of surgery in 18 patients, the common findings including widespread miliary nodules (14 cases, 77.8%), widespread adhesion (10 cases, 55.6%), adnexal mass (6 cases, 33.3%) and caseous necrosis substance (6 cases, 33.3%) were encountered. The patients underwent extended surgery including mesentery or pelvic lymph node resection (2 cases, 11.2%) and unilateral or bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (7 cases, 38.9%) (Tables 1 and 2).

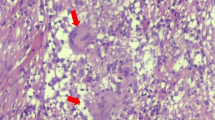

Frozen section was obtained in suspicious parts in 10 cases. Typical tuberculosis tubercles, consisting of epithelioid histiocytes, Langhans giant cell and caseous necrosis in granuloma, were detected in 10 cases (100%). Frozen sections obtained from various parts of the ovary, oviduct and omentum were diagnosed as chronic granulomatous inflammation with necrosis (Fig. 1).

Anti-tuberculosis chemotherapy

All the postoperative patients were referred to a phthisiologist. All patients were given quadruple anti-tuberculosis chemotherapy postoperatively.

Discussion

The therapies between APTB and advanced ovary cancer differ largely. APTB requires conservative quadruple anti-tuberculosis treatments while ovarian malignancy requires the extended surgery, chemotherapy and even radiotherapy. However, the diagnostic dilemma of APTB presents the technical hindrance for the proper therapies in these patients.

Female patients with APTB were younger than women with ovary tumors. Previous surveys showed the peak age to be between 20 and 40 years in women with APTB (Panoskaltsis et al. 2000). Our survey from 1996 to 2005 revealed similar results, the mean age was 28.9 ± 10.8 years with a range from 14 to 48 years.

APTB presents with nonspecific signs and symptoms such as abdominal pain, pelvic mass and ascites, and hence mimics ovarian cancer. The percentage of patients showing pelvic mass (90%) was the highest in this series. Although the most consistent finding in the literature was the presence of ascites, Muneef et al. (2001) differed in finding ascites present in only 61% of their patients. In our findings, ascites were also presented in 60% patients, along with weight loss in 40% patients. Moreover, 45% cases with abdominal distention and pelvic-abdominal pain were noted in 20 patients of the present series. Fever was the most common finding (73%) in the series reported by Muneef et al. (2001), but our results agree with most other studies in reporting about 30%.

There is always no clinical and radiological evidence of a primary pulmonary TB and the primary focus in the lungs usually heals completely (Marshall 1993). In our series, only 6 cases (33.3%) with the evidence of pulmonary TB were found. Positive family history maybe helpful; however, somewhat less than 30% patients have family history (Uzunkoy et al. 2004). In our series, only 1 case (5%) had family history of pulmonary TB.

Numerous studies have shown that the determination of CA125 raises the suspicion of ovarian cancer in women with a pelvic mass and ascites (Thakur et al. 2001; Barutcu et al. 2002; Lantheaume et al. 2003). However, elevation of serum CA125 may also be associated with many benign gynecologic pathologies, including pelvic inflammatory disease, endometriosis, fibroids, and even pregnancy or menstruation (Penna et al. 1993; Phyo et al. 2001), especially in younger patients. Therefore, CA125 is a nonspecific epithelial tumor marker. In the light of these finding, Thakur et al. suggested that the increased serum CA125 should always raise a suspicion of APTB (Thakur et al. 2001). In our series, 18 of 20 patients (90%) had elevated and variable CA125 with an average level 244U/ml (10.21–706.8 U/ml). The levels of CA125 in 5 cases were less than 100 U/ml, in 8 cases between 101 and 500 U/ml and higher than 500 U/ml in 5 cases.

Sometimes a strongly positive PPD is indicative of reactivation of TB, but it cannot be judged as TB since it does not always means infection (Bhansali 1977). PPD test is positive in 3 of 3 cases in this series. Slight or moderate anemia (85%), the elevated ESR and other tumor markers including AFP and CEA can also be detected. None of the earlier tests was specific for APTB.

Radiological investigations, including chest X-rays, ultrasound or CT scan abdomen and barium studies, are the mainstay in making presumptive diagnosis of abdominal TB (Bolukbas et al. 2005), but these findings were largely nonspecific. Ascites, omental thickening and mesenteric lymph nodes enlargement are also presented in other diseases such as primary malignant tumors, Crohn disease and lymphoma (Koc et al. 2006). In our series, pelvic mass and ascites were detected in 18 (90%) and 12 (60%) patients, respectively. Moreover, GIS evaluation was carried out in 12 patients but 3 cases (25%) were abnormal. Therefore, although the diagnosis made on the basis of radiological investigation is rapid and cheap, it cannot exclude completely other diseases.

Many malignancies, such as ovarian cancer, are associated with pelvic mass, ascites and elevated serum CA125 levels (Sheth 1996; Gleeson et al. 1993). In these patients, differential diagnosis is extremely difficult and needs surgical intervention. Preoperational abdominal paracentesis was unhelpful because the bacteriologic cultures and cytological studies of the ascitic fluid specimens were negative in all cases in this study. Laparoscopy and laparotomy can also be used as the effective methods to provide culturing ascites and tissues samples for histological and pathological diagnosis. However, recurrences have been reported in needle and trocars tracts, abdominal paracentesis and laparoscopy are reluctant to be performed in patients with a suspected ovarian malignancy (Kruitwagen et al. 1996). Introduction of trocars into the peritoneal cavity during laparoscopy evaluation should be performed carefully in patients with suspected adhesions. In our series, the adhesion pelvis was detected in 10 of 18 patients (55.6%), and laparoscopy was chosen as an additional diagnostic step in only one case.

Diagnostic laparotomy seems to be comparatively sufficient and safe methods and can avoid unnecessary surgery. Widespread military nodules (1–3 mm) on the peritoneal surfaces are the characteristic features for APTB. In our series, military nodules and caseous necrosis substance were presented in 14 and 6 of 18 cases (77.8 and 33.3%, respectively).

Histology of frozen sections or paraffin-embedded sections is mandatory. In our series, frozen section was employed in suspicious parts in 10 cases. Typical tuberculosis tubercles were detected, and frozen sections were diagnosed as chronic granulomatous inflammation with necrosis. Without frozen-section evaluation, parts of patients in the present series underwent unnecessary extended surgery. Nevertheless, smear and culture were largely unhelpful (Uzunkoy et al. 2004). In our cases, ascitic fluid was all negative for acid-fast bacilli stain and culturing.

Therefore, it is essential to establish more effective diagnostic procedures to identify the characteristic features of APTB. To sum up, clinical features, past and family history, biochemical tests and radiological evaluations may not be specific enough in differentiating from ovary cancer. Hence, ovary epithelial cancer diagnosis cannot be made solely to female patients with pelvic mass, ascites and the elevated CA125. APTB should be considered in all cases with these features. Diagnostic laparotomy is a direct and safe method, and intra-operative frozen section should be performed for the diagnosis of APTB and avoiding unnecessary operation.

References

Barutcu O, Erel HE, Saygili E, Yildirim T, Torun D (2002) Abdominopelvic tuberculosis simulating disseminated ovarian carcinoma with elevated CA-125 level: report of two cases. Abdom Imaging 27:465–470

Bhansali SK (1977) Abdominal tuberculosis. Am J Gastroenterol 67:324–327

Bolukbas C, Bolukbas FF, Kendir T, Dalay RA, Akbayir N, Sokmen MH, Ince AT, Guran M, Ceylan E, Kilic G, Ovunc O (2005) Clinical presentation of abdominal tuberculosis in HIV seronegative adults. BMC Gastroenterol 5:21

Gleeson NC, Nicosia SV, Mark JE, Hoffman MS, Cavanagh D (1993) Abdominal wall metastases from ovarian cancer after laparoscopy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 169:522–523

Groutz A, Carmon E, Gat A (1998) Peritoneal tuberculosis versus advanced ovarian cancer: a diagnostic dilemma. Obstet Gynecol 91:868

Karlan BY, Platt LD (1995) Ovarian cancer screening. The role of ultrasound in early detection. Cancer 76:2011–2015

Koc S, Beydilli G, Tulunay G et al (2006) Peritoneal tuberculosis mimicking advanced ovarian cancer: a retrospective review of 22 cases. Gynecol Oncol 103:565–569

Kruitwagen RF, Swinkels BM, Keyser KG, Doesburg WH, Schijf CP (1996) Incidence and effect on survival of abdominal wall metastases at trocar or puncture sites following laparoscopy or paracentesis in women with ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol 60:233–237

Lantheaume S, Soler S, Issartel B, Isch JF, Lacassin F, Rougier Y, Tabaste JL (2003) Peritoneal tuberculosis simulating advanced ovarian carcinoma: a case report. Gynecol Obstet Fertil 31:624–626

Marshall JB (1993) Tuberculosis of the gastrointestinal tract and peritoneum. Am J Gastroenterol 88:989–999

Miranda P, Jacops AJ, Roseff L (1996) Pelvic tuberculosis presenting as an asymptomatic pelvic mass with rising serum CA-125 levels: a case report. J Reprod Med 41:273–275

Muneef MA, Memish Z, Mahmoud SA, Sadoon SA, Bannatyne R, Khan Y (2001) Tuberculosis in the belly: a review of forty-six cases involving the gastrointestinal tract and peritoneum. Scand J Gastroenterol 36:528–532

Nistal de Paz F, Herrero Fernandez B, Perez Simon R et al (1996) Pelvic-peritoneal tuberculosis simulating ovarian carcinoma: report of three cases with elevation of the CA125. Am J Gastroenterol 91:1600–1601

Panoskaltsis TA, Moore DA, Haidopoulos DA et al (2000) Tuberculous peritonitis: part of the differential diagnosis in ovarian cancer. Am J Obstet Gynecol 182:740–742

Penna L, Manyonda Y, Amias A (1993) Intraabdominal miliary tuberculosis presenting as disseminated ovarian carcinoma with ascites and raised CA-125. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 100:51–53

Phyo P, Mantis JA, Rosner F (2001) Elevated serum CA125 and adnexal mass mimicking ovarian carcinoma in a patient with tuberculous peritonitis. Prim Care Update Ob/Gyns 8(3):110–115

Piura B, Rabinovich A, Leron E, Yanai-Inbar I, Mazor M (2003) Peritoneal tuberculosis-an uncommon disease that may deceive the gynecologist. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 110:230–234

Sheer TA, Coyle WJ (2003) Gastrointestinal tuberculosis. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 5:273–278

Sheth SS (1996) Elevated CA 125 in advanced abdominal or pelvic tuberculosis. Int J Gynecol Obstet 52:167–171

Thakur V, Mukherjee U, Kumar K (2001) Elevated serum cancer antigen 125 levels in advanced abdominal tuberculosis. Med Oncol 18:289–291

Uzunkoy A, Harma M, Harma M (2004) Diagnosis of abdominal tuberculosis: experience from 11 cases and review of the literature. World J Gastroenterol 10(24):3549–3647

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by grants from National “973”Key Basic Research and Development Program Foundation (No. 2009CB521808) and National Science Foundation of China (No. 30628029; 30672227; 30528012, 30600667).

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

X. Xi and L. Shuang contributed equally to this manuscript.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Xi, X., Shuang, L., Dan, W. et al. Diagnostic dilemma of abdominopelvic tuberculosis:a series of 20 cases. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 136, 1839–1844 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00432-010-0842-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00432-010-0842-7