Abstract

Recent studies estimated that about 20–30% of visits in a paediatric emergency department (PED) are inappropriate. Nonurgent visits have been negatively associated with crowding and costs, causing longer waiting and dissatisfaction among both parents and health workers. We aimed to analyze possible factors conditioning inappropriate visits and misuse in a PED. We performed a cross-sectional study enrolling children accessing an Italian PED from June 2022 to September 2022 who received a nonurgent code. The appropriateness of visits, as measured by the “Mattoni SSN” Project, comprises combination of the assigned triage code, the adopted diagnostic resources, and outcomes. A validated questionnaire was also administered to parents/caregivers of included children to correlate their perceptions with the risk of inappropriate visit. Data were analyzed using independent-samples t-tests, Wilcoxon-Mann–Whitney tests, chi-square tests, and Fisher’s exact tests. The factors that were found to be associated with inappropriate visits to the PED were further evaluated by univariable and multivariable logistic regression analyses. Almost half (44.8%) of nonurgent visits resulted inappropriate. Main reasons for parents/caregivers to take their children to PED were (1) the perceived need to receive immediate care (31.5%), (2) the chance to immediately perform exams (26.7%), and (3) the reported difficulty in contacting family paediatrician (26.3%). Inappropriateness was directly related to child’s age, male gender, acute illness occurred in the previous month, and skin rash or abdominal pain as complaining symptoms.

Conclusion: This study highlights the urgent need to finalize initiatives to reduce misuse in accessing PED. Empowering parents’ awareness and education in the management of the most frequent health problems in paediatric age may help to achieve this goal.

What is Known: • About 20–30% of pediatric urgent visits are estimated as inappropriate. • Several factors may be associated with this improper use of the emergency department, such as the misperception of parents who tend to overrate their children’s health conditions or dissatisfaction with primary care services. | |

What is New: • This study evaluated almost half of pediatric emergency department visits as inappropriate adopting objective criteria. • Inappropriateness was directly related to the child’s age, male gender, acute illness that occurred in the previous month, and skin rash or abdominal pain as complaining symptoms. Educational interventions for parents aimed at improving healthcare resource utilization should be prioritized. |

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

According to the American Medical Association, the term urgency identifies any circumstance that, “in the judgment of the patient, family, or decision-maker, requires immediate medical intervention” [1]. This concept implies both objective (illness’ severity and acuity) and subjective aspects (awareness of an imminent need for care), giving rise to the user’s expectation of rapid attention and resolution [2]. Emergency department (ED) overcrowding is a growing phenomenon in many countries worldwide, and it can also be observed in the paediatric setting [3,4,5]. The high level of utilization of ED services is overwhelmed by an inappropriate and heavy access for nonurgent conditions. It is estimated that around 20–30% of paediatric ED (PED) visits are inappropriate [6], with some authors indicating rates up to 70% [7]. All visits usually receiving a nonurgent code that could be managed at other services can be considered “inappropriate” [8]. This may negatively impact health professionals’ work, extending waiting time for patients [9], and reducing the quality of care due to delayed treatment[10]. Organizational problems have also been reported, including patients leaving the ED without being seen [11], inefficient use of hospital resources—such as the use of highly qualified personnel in nonurgent cases [12]—and increased costs [13].

There are several factors that may affect the overcrowding in a PED, first of all the misperception of parents and caregivers, who sometimes tend to overrate as urgent their children’s health conditions [14, 13]. Some studies also hypothesized that parents may not have trust in primary care services [15]. In particular, the difficulty in obtaining an appointment because of long waiting lists, the dissatisfaction and communication problems with the primary care staff, the efficiency of the PED related to available greater resources in the hospital, and the consequent higher quality of the provided care are among the mostly frequent reported parental reasons to prefer PED over their child’s family paediatrician [13, 16, 17].

In December 2003, the Italian government introduced the so-called “Mattoni SSN” project with the aim of evaluating the appropriateness of every ED visit based on the assigned triage code assigned, the adopted diagnostic resources, including the need for an additional specialist consultation, and the clinical outcome (admission or discharge) [18]. This system of classification was extensively applied in Italy, even in the paediatric field [7, 12].

The primary aim of this study was to objectively estimate inappropriate nonurgent visits in a PED. Our secondary aim was to identify socio-demographic or clinical factors and misperceptions possibly associated to improper ED use in a paediatric setting.

Methods

Study design

We conducted a cross-sectional study in a tertiary level PED at the University Hospital of Central Friuli in Udine, North-eastern Italy, covering an area of 530,000 residents, with a volume of 20,000 patients/year between the age of 0 and 16.

A previously validated questionnaire [6] was administered to parents and caregivers of participating children from 28 June 2022 to 9 October 2022. The responses were then analyzed and correlated with clinical data retrieved from the electronic hospital health system.

The study protocol was approved by the local Institutional Review Board (Prot IRB: 86/2022).

Population and inclusion criteria

Patients accessing PED between June and October 2022 were enrolled. A 4-level tag system based on paediatric criteria was used for triage [19]: white and green codes were classified as nonurgent/delayable conditions, while yellow and red codes were classified as non-delayable urgencies/emergencies needing an immediate intervention. Inclusion criteria were as follows: age between 0 and 16 years, nonurgent triage codes (white and green), obtained consent to participate to the study, and to fulfil the questionnaire. Patients with no retrievable data or whose parents/caregivers did not complete the questionnaire (< 80% answers) were excluded.

Data collection and instruments

The adopted paper-and-pencil 40-item questionnaire [6] was administered to all participating patients’ parents/caregivers. This validated questionnaire consisted of 38 multiple choice and 2 open-ended questions, focusing on three main areas: (1) clinical data about the child’s health conditions and reasons for accessing the PED; (2) use of community-based primary health services; and (3) sociodemographic data and information about the parents/caregivers’ ability to manage six common paediatric conditions. A research nurse invited parents in the waiting room to participate in the study.

Clinical data including age, information on complaining symptoms, treatments, or need for diagnostic exams were collected through electronic medical records used in the PED.

Study outcomes

The primary outcome was represented by the percentage of inappropriate accesses, estimated through the comparison of patient’s clinical data (triage code, age, vital parameters, medical interventions—therapies, tests, length of stay/observation in the PED, discharge diagnosis) with the “Mattoni” criteria. According to this method, white and green codes discharged “at home” or “the patient leaves the PED before the medical visit/during the investigation and/or before the report is closed”, with no need to perform any exam with the exception of the general visit, and who were not referred by primary care paediatrician, another specialist nor emergency care service, were considered inappropriate.

Social, demographic, and organizational characteristics of inappropriate access were tested for possible associations with parental misperceptions, based on data collected through the questionnaire proposed to parents.

Statistical analysis

The sample size estimate was obtained by assuming an expected frequency of inappropriate accesses of 20%, a margin of error of 5%, and a confidence level of 95%. Thus, the minimum sample size required for statistical purposes was equal to 246.

For the purposes of the analysis, some categorical variables were recoded. Continuous variables were summarized by mean and standard deviation (SD) and/or median and interquartile range (IQR) when the distribution of variables was not normal according to Shapiro–Wilk test. Categorical variables were described by frequency distributions. Frequency comparisons between the groups were performed using the chi-square test and, if necessary, with Fisher’s exact test, and t-tests or Wilcoxon-Mann–Whitney tests were applied to compare continuous variables, as appropriate. Missing answers were not considered in the analysis of the association between the variables.

Factors associated with inappropriate nonurgent visits in a PED (P < 0.10) were further assessed with univariable regression analysis, and only factors showing a bivariate association with the dependent variable at the significance level P < 0.05 were included in the multivariable logistic model. Multicollinearity was assessed with variance inflation factor (VIF), with values above 2.5 indicating considerable collinearity [20]. Possible answers were “very poor”, “poor”, “fair”, “good”, and “very good” and were transformed in a Likert scale scoring from 1 to 5, where 1 is “very poor” and 5 “very good”. The answer “I do not know” was categorized as missing value. Statistical significance was set at 2-sided P < 0.05. STATA (Release 17 StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) was used for analysis.

Results

Children’s baseline characteristics and inappropriate access to PED

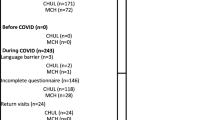

A total of 275 patients were initially enrolled, but 43 (16%) were excluded because a different color-code was assigned or parents failed to fully complete the survey. The final sample consisted of 232 patients. The baseline characteristics of the enrolled children and the results of the assessment of the presence of association with inappropriate access are shown in Table 1. Among children accessing PED for nonurgent conditions (white and green codes), 126 were males (54.3%), with a median age of 7 ± 8 years, and mostly first-born child (77/232, 59.5%). Only a few of them had a chronic disease (9/232; 3.9%) or had recently suffered from acute illness (27/232; 11.6%). More than half of patients reported to have not been in the PED in the last year (125/232, 53.9%), nor admitted to the hospital (165/232, 71.1%). More than one out of two accompaniers stated that they had made more than two visits to PED in previous years (120/232, 51.7%).

Overall, 104/232 (44.8%) visits in our PED were for nonurgent and inappropriate reasons, according to the “Mattoni criteria”. Male children were more likely to inappropriately access PED than females (inappropriate access: males, 65/126 (61.6%); females, 39/106 (36.8%); P = 0.024). Median age of children with inappropriate visit was lower than that of children with appropriate access (inappropriate access median age ± IQR, 6 ± 8; appropriate access median age ± IQR, 7 ± 7; P = 0.036). Being acutely ill in the last month (inappropriate access: acute disease in the last month, 18/27 (66.7); no acute disease in the last month, 85/203 (41.9%; P = 0.015)) and the number of visits to the PED in previous years also appear to be associated with inappropriate access to the PED (P = 0.006).

Most questionnaires (174/232, 75%) were completed by mothers. Parental mean age was 40.2 ± 6.9 years for mothers and 43.1 ± 7.9 years for fathers. Most parents had a high-school degree (mothers, 115/232, 49.6%; 118/232, fathers, 50.9%) or were graduated (mothers: 88/232, 37.9%; fathers: 72/232, 31.0%) and almost all mothers (196/232; 84.5%) and fathers (221/232, 95.3%) were employed. None of these variables showed association with inappropriateness (Supplementary Table 1).

Symptoms for accessing PED and inappropriate visits

Parents decided to access the PED for non-urgent reasons for various symptoms (Supplementary Table 2). The most common symptoms reported by participants were trauma/wounds (87/232; 37.5%), skin rash (22/232; 9.5%), and abdominal pain (22/232; 9.5%). Children visiting PED for trauma/injury were less likely to have inappropriate access than those accessing for a different sign/symptom (inappropriate access and visit for trauma/wound: 25/87 (28.7%); inappropriate access and visit for another sign/symptom: 75/134 (56.0%); P < 0.001)). In contrast, children who accessed the PED for skin rash (inappropriate access and visit for skin rash: 16/22 (72.7%); inappropriate access and visit for another sign/symptom: 84/199 (42.2%); P = 0.006), abdominal pain (inappropriate access and visit for abdominal pain: 15/22 (68.2%); inappropriate access and visit for another sign/symptom: 85/199 (42.7%); P = 0.023), and crying (inappropriate access and visit for crying: 5/6 (83.3%); inappropriate access and visit for another sign/symptom: 95/215 (44.2%); P = 0.094) were more likely to access the PED inappropriately.

Reasons for accessing PED and inappropriate visits

The most frequent reasons for accessing PED were the perceived need for urgent care (73/232, 31.5%), the availability of rapid medical tests (62/232, 26.7%), and the impossibility to contact the family paediatrician (61/232, 26.3%) (Table 2). Children for whom the family paediatrician was not reached (vs. those who did not report this reason for access the PED) were more likely to have inappropriate access to PED (inappropriate access and impossibility to contact the family paediatrician: 36/61 (59%); inappropriate access and visit other reasons: 67/167 (40.1%); P = 0.011) (Table 2). In addition, those who reported that they had already contacted the paediatrician but that the situation had worsened (3/14, 21.4%) appeared to be less likely to inappropriately access the PED than those who entered for another reason (100/214, 46.7%), although the association did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.065) (Table 2).

Diagnosis of nonurgent visits

Among nonurgent visits to PED, most had a discharge diagnosis of trauma/wounds (63/232, 27.2%) or pain (52/232, 22.4%), and most of those who presented with these diagnoses had appropriate access to the PED (trauma/wounds: 51/63, 81.0%; pain: 36/52, 69.2%). In contrast, more than 70% of those diagnosed with a dermatological problem or gastrointestinal diseases made an inappropriate visit to the PED. Furthermore, 40% of inappropriate codes were discharged for one of those two health issues (dermatological problems: 23/104, 22.1%; gastrointestinal diseases: 21/104, 20.2%) (Table 3).

Ability in the management of symptom and visit for the symptom

Participants also described their ability to manage common paediatric symptoms: most participants reported being good at managing fever (mean score ± SD; 4.0 ± 0.9) and less confident in the management of respiratory distress (mean score ± SD; 2.8 ± 1.1). On average, respondents reported merely a discrete ability to handle skin rash (mean score ± SD; 3.4 ± 1.0). Answers were furthermore evaluated for possible relationships with visit for the symptom. Parents of children who accessed the PED complaining cough showed lower perceived ability to manage this symptom than those who were visited for another health problem (mean score ± SD; 3.25 ± 0.62 vs. 4.02 ± 0.83; P < 0.05). No other significant relationships emerged (Table 4).

Univariable and multivariable logistic regression analyses

The results of the univariate and multivariate analysis are presented in Table 5. Male children and access for skin rash were found independent risk factors for inappropriateness and were associated with a twofold [OR: 2.2 (95% CI, 1.2–4.1); P = 0.010] and threefold [OR: 3.0 (95% CI, 1.0–9.0; P = 0.044] increase in the likelihood of inappropriate access, respectively.

In the multivariate analysis, although not reaching statistical significance, acute illness in the last month [OR: 2.2 (95% CI, 0.9–5.6); P = 0.086] and visit for abdominal pain (vs. visit for another sign/symptom) [OR: 2.7 (95% CI, 0.9–7.6); P = 0.066] were also directly associated with inappropriate access, whereas visit for trauma/injury (vs. visit for another sign/symptom) appeared indirectly associated with inappropriate access [OR: 0.5 (95% CI, 0.3–1.0); P = 0.051]. Multivariate did not exhibit multicollinearity (VIF < 2.5).

Benefits of providing additional information to parents

Most parents felt it was helpful or very helpful to receive more information concerning the management of typical paediatric health issues. Respiratory distress was by far the symptom with the highest percentage of parents who found it very helpful to receive more information (140/232, 60.3%). For other health problems, however, parents also showed interest, since for any given symptom at least 4 out of 10 people considered it very useful to receive additional information (Supplementary Table 3).

Discussion

This is the first study evaluating possible correlations between the risk of inappropriate PED visits estimated according to objective criteria and the perception of parents/caregivers of their child’s health condition.

Almost half of the total accesses in our PED were assessed as improper (44.8%). The percentage is similar to that reported in other studies [6, 7, 12] and is also in line with estimates of 40–59% of PED visits manageable in less complex settings such as primary healthcare services [21, 22]. Ideally users should consult their general practitioner/family paediatrician for nonurgent and urgent situations, and then they can be referred to the PED if necessary. Specific PED to primary care clinic transfer protocol for nonurgent visits of established patients have been successfully adopted in USA, by saving up to 100.000$ per year [23].

However, as shown in this study, more frequent reasons for preferring to access the PED than primary care services were the perceived need for urgent care, the difficulty in contacting family paediatrician and in obtaining rapid medical tests. Moreover, the lacked involvement of the primary healthcare referral resulted to be associated—although not significantly—with approximately twofold higher risk of inappropriate visit. On the other hand, those who had been previously evaluated by their family paediatrician (vs. those who did not report visiting PED for this reason) were at low risk of inappropriateness. These findings are supported by a recent systematic review that showed the presence of direct association between inappropriate visits and several factors such as the difficulty of receiving timely access to primary care services and the perceived benefit of using PED rather than other services [2]. Moreover, children accessing outside working hours are less likely to visit the PED inappropriately [3]. In fact, most caregivers acknowledge the nonurgent nature of their children’s complaints and refrain from visiting the PED at night time, but prefer it to a primary care’s office because of the difficulties to obtain an appointment as close in time as needed, or due to the assumption to get a faster treatment and a higher quality of diagnostics at a PED [3]. The phenomenon may suggest the need for improvements in community and primary healthcare services, as the dissatisfaction emerged in this setting may affect parents’ decision to seek help in hospital [3, 24,25,26].

Male children were at higher risk of improper visit, as already outlined by previous papers [15, 14]. This may be related to the relative higher incidence of infectious diseases in boys, as sex hormones impact on the T-helper 1/T-helper 2 cytokine balance [27]. On the other hand, older age resulted a protective factor against the risk of nonurgent evaluation, even if this did not reach statistical significance in multivariate model; this finding may be related to some emotional factors: parents usually perceive the urgent need to be reassured as soon as possible about their children’s condition, in particular when they are younger [15, 24, 28]. The inability of infants/toddlers to make their condition explicit can generate frustration in their caregivers. Moreover, the misperception of a higher risk to contract any infection at school was also evaluated as reason to seek care in a hospital setting [3].

Among psychosocial and clinical factors evaluated, respiratory distress represented the symptom parents felt to be less able to manage with. Therefore, it should be not surprising that during the COVID-19 pandemic a 70% decrease in the number of PED visits was globally registered, resulting in a reduction of the workload of PED accesses, especially for those unnecessary [3, 29]. In fact, the most significant drop was related to infectious and respiratory cases [3, 30]. Parents often reported to feel not able to manage their children’s clinical conditions, even about common symptoms such as fever or cough. This is consistent with our results showing that parents’ perceived ability for some common health problems, such as respiratory distress or skin rash, was on average at or below the discrete level. This appeared as an issue in particular with first-time parents, who may lack experience in dealing with a sick child [21, 25]. Empowering caregivers’ awareness and education in the management of the most frequent health problems in paediatric age may help their autonomy and possibly reduce inappropriate visits in PED. Parents who are confident in dealing with a sick child usually know when to involve a doctor [24].

Approximately 7 out of 10 of those who accessed for rash had inappropriate access. Indeed, visiting PED for that issue was found directly associated with inappropriate visit. This result can be explained by the fact that most parents do not feel capable enough to handle rashes. Dermatologic conditions continue to comprise a significant number of ED accesses in the paediatric population, and patients presenting with these conditions were more likely to be triaged as nonurgent or semi-urgent than those without dermatologic conditions [31]. Only 2% of patients with dermatologic conditions required further observation or admission [31]. Similar findings were also shown by Biagioli et al., and parents stated to wish for more information about the management of this condition [6].

As our findings support the hypothesis that the overuse of the PED may be mostly due to a parental attitude towards a general overuse of healthcare resources, priority should be given to educational interventions for parents aimed to improve healthcare resources utilization [32]. A British randomized, prospective cohort study compared two groups of parents to assess the impact of a short educational video on the management of common symptoms [33]. Even though knowledge and assessment of childhood fever improved, PED use for minor complaints did not decrease in practice. A second study carried out in Texas evaluating educational measures for parents of children with asthma showed that parental education is related with a better understanding of the disease and boosts self-confidence in handling asthmatic treatments [34]. Moreover, the number of times children with asthma presented to the PED resulted significantly reduced after these educational measures [34].

Also, public health campaigns may help increase public awareness regarding primary care services and consequently lead to reduce PED attendances [21]. However, the evidence of effectiveness of these strategies appears scant and generally of low quality [35,36,37].

Although parents report that education on the urgency of paediatric conditions would be helpful, substantial reduction of paediatric nonurgent ED use may require improvements in families’ primary care office access, efficiency, experiences, and appointment scheduling [13]. Extended office hours may be the most effective practice change to reduce PED use. Primary care practices should prioritize the most effective enhanced access services and communicate existing services to families [38].

Limits and strengths

Some limits of this study should be highlighted. The number of collected questionnaires was slightly lower than initially estimated by the sample size (232 enrolled patients vs. 246 expected), but the data collection was performed during summer months, and as reasons for accessing PED are influenced by seasonality, the enrolment may be also affected as well.

The survey was available only in Italian; therefore, some patients have been excluded, and this may constitute an important selection-bias. However, even if some reports showed that foreign patients may be at higher risk of inappropriateness [39], evidence is still unclear as other studies demonstrated that immigrants did not access to PED more frequently than Italian children [40].

Among the strengths of this study, we adopted an objective tool to assess the appropriateness of accesses in a PED. In fact, as shown by a recently published Canadian study, clinician judgment alone is poorly reliable for assessing appropriateness of PED visit, suggesting the implementation with more objective criteria [41]. We similarly chose to use a previously validated questionnaire to evaluate parents’ characteristics and perceptions of their children’s condition [6, 7]. A quite large group of possible determinants and factors were tested to evaluate associations with improper use of PED.

Conclusions

At least half of PED visits at our centre were inappropriate, and parental reasons for inappropriate presentations most commonly reflected difficulties in contacting primary care paediatricians and the perceived need for a quick work-up and treatment. Several factors may be associated to the misuse of PED services, and empowering parents’ awareness and education in the management of the most frequent health problems in paediatric age may help to reduce this habit. Learning also from the experience of the recent COVID-19 pandemic, the real challenge remains to move health care systems towards more integrated models between hospitals and community services.

Availability of data and materials

Data may be available upon specific request.

References

Chaet DH (2018) AMA code of medical ethics’ opinions related to urgent decision making. AMA J Ethics 20:464–466. https://doi.org/10.1001/journalofethics.2018.20.5.coet1-1805

Montoro-Pérez N, Richart-Martínez M, Montejano-Lozoya R (2023) Factors associated with the inappropriate use of the pediatric emergency department. A systematic review. J Pediatr Nurs 69:38–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedn.2022.12.027

Guckert L, Reutter H, Saleh N et al (2022) Nonurgent visits to the pediatric emergency department before and during the first peak of the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Pediatr 2022:7580546. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/7580546

Ma H, S M, K B, et al (2007) Emergency department overcrowding and children. Pediatr Emerg Care 23. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.pec.0000280518.36408.74

Ben-Isaac E, Schrager SM, Keefer M, Chen AY (2010) National profile of nonemergent pediatric emergency department visits. Pediatrics 125:454–459. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2009-0544

Biagioli V, Pol A, Gawronski O, et al (2021) Pediatric patients accessing accident and emergency department (A&E) for non-urgent treatment: why do parents take their children to the A&E? Int Emerg Nurs 58:101053. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ienj.2021.101053

Calicchio M, Valitutti F, Della Vecchia A, et al (2021) Use and misuse of emergency room for children: features of walk-in consultations and parental motivations in a hospital in Southern Italy. Front Pediatr 9:674111. https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2021.674111

Bonetti M, Melani C (2019) Il ruolo degli accessi impropri in pronto soccorso nella provincia autonoma di Bolzano. BEN

Bambi S, Ruggeri M, Sansolino S et al (2016) Emergency department triage performance timing. A regional multicenter descriptive study in Italy. Int Emerg Nurs 29:32–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ienj.2015.10.005

Haasz M, Ostro D, Scolnik D (2018) Examining the appropriateness and motivations behind low-acuity pediatric emergency department visits. Pediatr Emerg Care 34:647. https://doi.org/10.1097/PEC.0000000000001598

Alberto C, Francesca M, Giulia G, et al (2018) “Should I stay or Should I go”: patient who leave emergency department of an Italian third-level teaching hospital. Acta Biomed 89:430–436. https://doi.org/10.23750/abm.v89i3.7596

Vedovetto A, Soriani N, Merlo E, Gregori D (2014) The burden of inappropriate emergency department pediatric visits: why Italy needs an urgent reform. Health Serv Res 49:1290–1305. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.12161

Berry A, Brousseau D, Brotanek JM et al (2008) Why do parents bring children to the emergency department for nonurgent conditions? A qualitative study. Ambul Pediatr 8:360–367. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ambp.2008.07.001

Akbayram HT, Coskun E (2020) Paediatric emergency department visits for non-urgent conditions: can family medicine prevent this? Eur J Gen Pract 26:134–139. https://doi.org/10.1080/13814788.2020.1825676

McHale P, Wood S, Hughes K et al (2013) Who uses emergency departments inappropriately and when - a national cross-sectional study using a monitoring data system. BMC Med 11:258. https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-11-258

Fieldston ES, Alpern ER, Nadel FM et al (2012) A qualitative assessment of reasons for nonurgent visits to the emergency department: parent and health professional opinions. Pediatr Emerg Care 28:220–225. https://doi.org/10.1097/PEC.0b013e318248b431

Brousseau DC, Nimmer MR, Yunk NL et al (2011) Nonurgent emergency-department care: analysis of parent and primary physician perspectives. Pediatrics 127:e375–381. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2010-1723

Mattoni SSN - Obiettivi generali. http://www.mattoni.salute.gov.it/mattoni/paginaMenuMattoni.jsp?id=1&menu=obiettivi&lingua=italiano. Accessed 21 May 2023

Zangardi T, Da Dalt L (2008) Il triage pediatrico. Piccin-Nuova Libraria, Padova, Italy

Johnston R, Jones K, Manley D (2018) Confounding and collinearity in regression analysis: a cautionary tale and an alternative procedure, illustrated by studies of British voting behaviour. Qual Quant 52:1957–1976. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-017-0584-6

Unwin M, Kinsman L, Rigby S (2016) Why are we waiting? Patients’ perspectives for accessing emergency department services with non-urgent complaints. Int Emerg Nurs 29:3–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ienj.2016.09.003

Neill S, Roland D, Thompson M et al (2018) Why are acute admissions to hospital of children under 5 years of age increasing in the UK? Arch Dis Child 103:917–919. https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2017-313958

Frazier SB, Gay JC, Barkin S, et al (2022) Pediatric emergency department to primary care transfer protocol: transforming access for patients’ needs. Healthc (Amst) 10:100643. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hjdsi.2022.100643

Butun A, Linden M, Lynn F, McGaughey J (2018) Exploring parents’ reasons for attending the emergency department for children with minor illnesses: a mixed methods systematic review. Emerg Med J emermed-2017–207118. https://doi.org/10.1136/emermed-2017-207118

Hendry SJ (2005) Minor illness and injury: factors influencing attendance at a paediatric accident and emergency department. Arch Dis Child 90:629–633. https://doi.org/10.1136/adc.2004.049502

Williams A, O’Rourke P, Keogh S (2009) Making choices: why parents present to the emergency department for non-urgent care. Arch Dis Child 94:817–820. https://doi.org/10.1136/adc.2008.149823

Muenchhoff M, Goulder PJR (2014) Sex differences in pediatric infectious diseases. J Infect Dis 209:S120–S126. https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jiu232

Costet Wong A, Claudet I, Sorum P, Mullet E (2015) Why do parents bring their children to the emergency department? A systematic inventory of motives. Int J Family Med 2015:978412. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/978412

Liguoro I, Pilotto C, Vergine M et al (2021) The impact of COVID-19 on a tertiary care pediatric emergency department. Eur J Pediatr 180:1497–1504. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-020-03909-9

Rabbone I, Tagliaferri F, Carboni E et al (2021) Changing admission patterns in pediatric emergency departments during the COVID-19 pandemic in Italy were due to reductions in inappropriate accesses. Children (Basel) 8:962. https://doi.org/10.3390/children8110962

Collier EK, Yang JJ, Sangar S et al (2021) Evaluation of emergency department utilization for dermatologic conditions in the pediatric population within the United States from 2009–2015. Pediatr Dermatol 38:449–454. https://doi.org/10.1111/pde.14476

Riva B, Clavenna A, Cartabia M et al (2018) Emergency department use by paediatric patients in Lombardy Region, Italy: a population study. BMJ Paediatr Open 2:e000247. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjpo-2017-000247

Baker MD, Monroe KW, King WD et al (2009) Effectiveness of fever education in a pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care 25:565–568. https://doi.org/10.1097/PEC.0b013e3181b4f64e

Agusala V, Vij P, Agusala V et al (2018) Can interactive parental education impact health care utilization in pediatric asthma: a study in rural Texas. J Int Med Res 46:3172–3182. https://doi.org/10.1177/0300060518773621

Sturm JJ, Hirsh D, Weselman B, Simon HK (2014) Reconnecting patients with their primary care provider: an intervention for reducing nonurgent pediatric emergency department visits. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 53:988–994. https://doi.org/10.1177/0009922814540987

Yoffe SJ, Moore RW, Gibson JO et al (2011) A reduction in emergency department use by children from a parent educational intervention. Fam Med 43:106–111

Ismail SA, Gibbons DC, Gnani S (2013) Reducing inappropriate accident and emergency department attendances: a systematic review of primary care service interventions. Br J Gen Pract 63:e813–e820. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp13X675395

Zickafoose JS, DeCamp LR, Prosser LA (2013) Association between enhanced access services in pediatric primary care and utilization of emergency departments: a national parent survey. J Pediatr 163(1389–1395):e1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.04.050

Scotto G, Saracino A, Pempinello R et al (2005) Simit epidemiological multicentric study on hospitalized immigrants in Italy during 2002. J Immigr Health 7:55–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-005-1391-z

Grassino EC, Guidi C, Monzani A et al (2009) Access to paediatric emergency departments in Italy: a comparison between immigrant and Italian patients. Ital J Pediatr 35:3. https://doi.org/10.1186/1824-7288-35-3

Paul JE, Zhu KY, Meckler GD et al (2020) Assessing appropriateness of pediatric emergency department visits: is it even possible? CJEM 22:661–664. https://doi.org/10.1017/cem.2019.473

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

I.L. wrote the first draft of the manuscript and led the project. A.R. collected data. Y.B. and L.C. performed the whole statistical analysis. Y.B. also prepared tables and supplementary material. Y.B, L.C., A.P., C.P. and P.C. critically revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the local International Review Board (IRB-DAME Prot. IRB 86/2022—Tit III cl 3 fasc. 8/2022) in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Communicated by Peter de Winter

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Liguoro, I., Beorchia, Y., Castriotta, L. et al. Analysis of factors conditioning inappropriate visits in a paediatric emergency department. Eur J Pediatr 182, 5427–5437 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-023-05223-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-023-05223-6