Abstract

Results of community-based childhood obesity intervention programs do not provide strong evidence for their effectiveness. In this study, we evaluated the effect of the Thao-Child Health Program (TCHP), a community-based, multisetting, multistrategy intervention program for healthy weight development and lifestyle choices. In four Catalan cities, a total of 2250 children aged 8 to 10 years were recruited. Two cities were randomly selected for the TCHP intervention, and two cities followed usual health care policy. Children were selected from 41 elementary schools. Weight, height, and waist circumference were measured at baseline and after a mean follow-up of 15 months. Physical activity and adherence to the Mediterranean diet were measured with validated questionnaires. Generalized estimating equations (GEE) models were fitted to determine the intervention’s effect on body mass index (BMI) z-score, waist-to-height ratio, Mediterranean diet adherence, and physical activity. Fully adjusted models revealed that the intervention had no significant effect on the BMI z-score, incidence of general and abdominal obesity, Mediterranean diet adherence, and physical activity. Waist-to-height ratio was significantly lower in controls than in the intervention group at follow-up (p < 0.004).

Conclusions: The TCHP did not improve weight development, diet quality, and physical activity in the short term.

What is Known: • There is inconsistent evidence for the efficacy of school-based childhood obesity prevention programs. • There is little evidence on the efficacy of childhood obesity intervention programs in other settings. | |

What is New: • This paper contributes information about the efficacy of a multisetting and multistrategy Community Based Intervention (CBI) program that uses the municipality as its unit of randomization. • This CBI had no effect on the prevention and treatment of childhood obesity in the short term. |

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Childhood obesity, one of the most challenging problems for public health policy, is highly prevalent in south European countries [1]. Recently published data on obesity prevalence paints a worrying picture for Spain. About 39% of Spanish children and adolescents are overweight or obese [35] and 16.5% have abdominal obesity [36]. Cardiometabolic health worsens in obese children, creating demand for the implementation of intervention programs to curb this epidemic [25]. Obesity has a multifactorial and multilevel etiology, with lifestyle choices such as diet and physical activity serving as a driving factor for this global epidemic [38]. The implementation of multicomponent programs that include several obesity-related targets is theoretically a promising intervention in treating overweight and obesity [30].

A systematic review and meta-analysis identified ten studies of the efficacy of community-based interventions (CBIs) to prevent childhood obesity [41]. Although three of the studies showed a significant reduction in body mass index (BMI) z-score, intervention and assessment methodologies were not homogenous. The level of evidence about CBI efficacy to prevent childhood obesity was moderate, based on the criteria of Wang and colleagues. None of these studies used municipalities as the community setting in a randomization strategy, and none were carried out in Spain. The EPODE methodology [8], created as a continuation of the Fleurbaix Laventie Ville Santé study [33], paved the way for the Thao-Child Health Program (TCHP). The TCHP is a multisetting and multistrategy CBI to prevent childhood obesity that was designed for implementation by municipalities in Spain [18].

The objective of this study was to determine the efficacy of the TCHP program on BMI and waist-to-height ratio as the main outcome, and dietary quality and physical activity as the secondary outcome, in children aged 8 to 10 years from four selected Catalan municipalities.

Methods

Study design and population

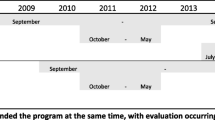

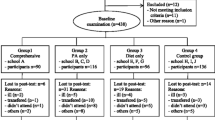

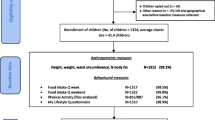

The TCHP is a community-based health program with municipalities as the community setting. Therefore, we chose a randomized cluster design with municipalities as unit of randomization for the POIBC study (acronym for Prevención de la Obesidad Infantil: Un modelo de Base Comunitaría, a Spanish study on effects on childhood obesity of a communitarian lifestyle intervention). The intervention lasted two academic years (2012–2014) with an average follow-up of 15 months. The project was approved by the local Ethics Committee (CEIC-PSMAR, Barcelona, Spain). Parental written consent was obtained on behalf of each of the 2250 children aged 8 to 10 years recruited from elementary schools (4th and 5th grade) in four Catalan cities (Sant Boi de Llobregat, Terrassa, Molins de Rei, and Gavà), located on the outskirts of Barcelona, but within the metropolitan area. Two municipalities, Sant Boi de Llobregat and Terrassa, were randomly selected with the R pseudo-random number generator for TCHP implementation, and Molins de Rei and Gavà served as control cities (Online Resource 1). Intervention cities had larger populations (Sant Boi de Llobregat = 83,107 inhabitants; Terrassa = 215,517 inhabitants) than the control cities (Gavà = 46,326 inhabitants; Molins de Rei = 25,152 inhabitants), which affected the number of schools per city and the number of participants. All schools in each of the four cities were invited to participate, but the school participation rate was higher in control cities than in the larger intervention cities. All children aged 8 to 10 years (4th and 5th grade of primary education) from the participating schools were invited (n = 2557). A signed informed consent was obtained from 89.6 and 86.7% of those families in the intervention and control cities, respectively (Online Resource 2). After excluding children with missing anthropometric data at baseline or main outcome data at follow-up, 2086 participants remained for analysis (974 in the intervention schools and 1112 in the control schools).

Intervention

Aim and general description

The main goal of the POIBC study was to assess the effectiveness of the TCHP, a CBI to prevent childhood obesity through healthy lifestyles promotion to children and their families. The TCHP implementation (Online Resource 3) was led by the city council, which appointed a local coordinator. In both intervention cities, the coordinator was selected from the community health department. The theoretical framework of the program is based on the attitude–social influence–self-efficacy (ASE) model [13], social marketing strategies used in the public health field [19], and CBI guidelines for obesity prevention [23, 43]. In addition, the emotional approach was an important element considered in the development of each health promotion material or activity [3]. At the final evaluation, Sant Boi de Llobregat had implemented eight community activities and Terrassa had implemented seven community activities (Table 1). To reinforce the health messages transmitted through the community activities, the teaching activities and the educational material, a paper-folding game was distributed each year, as shown in Table 2. The Thao Foundation coordinated the resources and networks that developed the public health strategy and created the graphic materials and CBI activities for all local key sectors. All activities were recorded by the Thao foundation. The TCHP closely followed the TIDieR checklist on reporting interventions [21]. Qualitative and quantitative process assessment was performed by the Thao Foundation. The perception of strengths and weaknesses of the intervention program was recorded by local coordinators.

Furthermore, it offered initial and follow-up training and ongoing support to local coordinators and their teams and provided the annual evaluation protocol for each town involved. All communication was delivered by multiple channels. The Online Resource 4 contains a detailed description of the thematic focus of the intervention, the organisms and personnel responsible for intervention and implementation, and the community activities, teaching activities, educational material, full press release introducing the project to the communities, and examples of the intervention.

Outcome measures

Anthropometric variables

Anthropometric measurements were assessed by trained personnel on the first day of the intervention at each school; each child wore a t-shirt, light trousers, and no shoes. Following a standard protocol [44], weight (to nearest 100 g), height, and waist circumference (both to nearest 1 mm) were measured using an electronic scale (SECA 813), a portable SECA 213 stadiometer, and a flexible non-stretch metric tape, respectively. Waist circumference was measured in the narrowest zone between the lower costal rib and iliac crest, in the supine decubitus and vertical positions. Measuring devices were systematically calibrated. BMI z-score was computed using age- and sex-specific reference values from the World Health Organization (WHO) [11]. Obesity was defined as a BMI > 2 SD from the mean of the WHO reference population. Waist-to-height ratio (WHtR) was calculated, and abdominal obesity was defined as a WHtR ≥ 0.5.

Lifestyle

The assessment of lifestyle variables has been described in detail elsewhere [17]. In brief, lifestyle data was self-reported using an online system. Data were collected in schools with the assistance of trained field researchers at baseline and at follow-up, using two instruments, KIDMED and the Physical Activity Questionnaire for Children (PAQ-C). The KIDMED index, based on a 16-item questionnaire [37], was created to estimate adherence to the Mediterranean diet in children and young adults, incorporating the principles that sustain Mediterranean dietary patterns and those that undermine it. The PAQ-C asks about various activities to determine the child’s physical activity (PA) level over the previous 7 days [28] and provides a summary PA score derived from nine items.

Other variables

Parental education level was collected and categorized into five levels: (i) no schooling, (ii) primary school, (iii) secondary school, (iv) technical or other university degree, and (v) higher (graduate-level) university degree.

Data collection

All variables were collected from all participating children and their families in the intervention and control cities at baseline and at a mean follow-up of 15 months.

Statistics

Student t for continuous variables and chi-square test for categorical variables were used to compare groups. Given that randomization to intervention was performed at the municipality level (clusters), generalized estimating equation (GEE) models were fitted to assess intervention effect on BMI z-score, WHtR, adherence to the Mediterranean diet, and PA [26].

Final models with anthropometric variables at follow-up as the outcome were adjusted for six baseline covariates: age, sex, mother’s educational level, adherence to the Mediterranean diet, PA, and the corresponding anthropometric variable (function “mgee” from R-packagesaws). Final models with lifestyle variables at follow-up as the outcome were adjusted for five baseline covariates: age, sex, mother’s educational level, BMI z-score, and the corresponding lifestyle variable. Children with obesity and those with abdominal obesity at baseline were excluded from analysis in order to determine the effect of the intervention on the incidence of obesity and abdominal obesity, respectively. It was not possible to fully adjust models to assess the effect of the intervention on obesity, due to convergence problems in the determination of the estimated effect in the interactive algorithm. Therefore, models were adjusted only for sex and age. Due to the small number of clusters (municipalities), GEE models estimation was followed by t test with the Kauermann and Carrol-corrected sandwich estimator or by the Wald t test with the FG-corrected sandwich estimator, depending on the variation in cluster size (function “saws” from R package saws).

FG-corrected sandwich estimation is not possible with mixed models. For this reason, we applied GEE models for the analyses. Missing data for variables included in the models were completed using multivariate imputation by chained equations, which yielded 20 multiple imputed datasets (The Multiple Imputation by Chained Equations [MICE] R package). Variables used in the imputation process were those related to missingness on the exposure variables. Analyses were carried out in each of the 20 multiple imputed datasets and then estimates of intervention effects were combined (MIcombine function, “mitools” R package). The possible bias of association estimates induced by non-random missingness was corrected by this multiple imputation process. Sensitivity analysis was stratified by sex. Comparison of participant characteristics was performed with the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS version 18.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Differences between the intervention and control group were considered significant if p < 0.05.

Results

Table 1 describes the materials provided to TCHP leadership teams for distribution in each intervention city. Qualitative process assessment revealed the following strengths: (i) the municipality-based, multistrategy intervention; (ii) attractive and well-planned and structured health promotion material such as the Thao intervention program characters (Thaoins), which capture children’s attention; and (iii) the successful assessment process. In contrast, lack of time to carry out all the proposed activities and the necessity of more community outreach were identified as program weaknesses. Quantitative process analysis showed a scaling of more than 8.0 points for each assessment criteria (Online Resource 5).

Table 3 shows baseline and follow-up characteristics of the study participants. Compared to the intervention group at baseline, children in the control group were younger and had lower waist circumferences, higher adherence to the Mediterranean diet, and higher PA levels; there was also lower prevalence of boys and abdominal obesity in the control group. Lower maternal education was more frequent in the intervention group, compared to controls. At follow-up, children in the control group had a significantly lower WHtR compared to children in the intervention group.

Sex- and age-adjusted GEE models revealed no intervention effect on changes in BMI z-score, KIDMED index, PAQ-C, or incidence of general and abdominal obesity (Table 4). Controlling additionally for baseline values of the outcome variables and parental educational status did not meaningfully alter the effect size of the intervention. In fully adjusted GEE models, WHtR was 0.005 lower in the control group than in the intervention group. Nonetheless, the effect size of the intervention was clinically irrelevant.

Sensitivity analysis revealed that the intervention’s effect on anthropometric and lifestyle variables was similar in boys and girls (Online Resource 6).

Discussion

Implementation of the TCHP in two Catalan cities had no significant effect on weight development, obesity incidence, or changes in diet quality and PA after two school years (15 months), compared to the two control cities.

Evidence of the efficacy of CBI in the prevention of childhood obesity is still scarce [5, 7, 41]. The systematic review by Bleich and colleagues [7] describes four studies [9, 12, 15, 34] that found slight but significant changes in BMI or BMI z-score. The main characteristics of these studies, compared with those that showed no effect, are long follow-up periods (from 24 to 48 months), a focus on young children (aged 2 to 8 years), a quasi-experimental design that allowed the inclusion of multiple intervention components (combining healthy diet and PA promotion policies and activities), and the inclusion of multiple settings (school, family, and the community). In contrast to the TCHP, none of these studies chose municipalities as the community setting for randomization and intervention implementation. However, TCHP intervention components and settings in the present study have similarities with the four effective interventions previously described [7], such as a combined focus on PA and dietary behavior (considered essential to tackle the childhood obesity epidemic) [29, 32] or the extension of the CBI to multiple settings [43]. Conversely, regarding the shared components of those four effective interventions, the TCHP model does not have the capacity to promote changes in environmental or structural policies that can favor the availability of healthy food or intensify physical activity strategies implemented in the participant communities. The Thao Foundation had no regulatory authority, which likely limited the intervention success because the multilevel etiology of childhood obesity could not be addressed. The health promotion strategies applied at the local level in the CBI model should be accompanied by policies and regulations in order to increase the likelihood of effectiveness [20, 27, 39]. Following the socio-ecological models of health determinants [10], the TCHP only influenced individual lifestyles and community strategies, not the structural determinants.

Moreover, the POIBC study included older children (8–12 years old), compared with the effective interventions identified in the review article. The preventive power of health promotion strategies may be higher when younger children are the target population [6, 31]. Families are more open and self-confident about introducing daily lifestyle changes in during early childhood development stages [16, 24].

The length of follow-up in the POIBC study is another difference (15 vs 24 months, the minimum in the effective CBI initiatives). A longer initial period is needed to build the local institutional networks through which the intervention is implemented. This increases the time needed to achieve positive changes, first in lifestyle and then in the effect on BMI. In this sense, the lack of results observed in the POIBC study could potentially be reversed after a longer follow-up.

As the field still has only moderate evidence on the effectiveness of intervention programs to address childhood obesity, the TCHP results are similar to several other CBI studies [7, 41]; only four strategies have produced significant results, and all had low effect size. In summary, based on this evidence it seems that the key elements for CBI success are the settings involved, the intervention components, the length of follow-up, and the ages of the participants [5, 7, 41].

This paper contributes information about the efficacy of a CBI that uses the municipality as its unit of randomization. No previous evidence of this approach was found, and more is needed in this field of research. Following the WHO recommendations [45], a CBI implemented in a whole municipality requires a more flexible implementation process in order to engage and encourage the different key settings (schools, health centers, markets, city council, etc.). The most successful CBI for childhood obesity prevention has multiple components that are designed and implemented according to the local context. Accordingly, it is not possible to provide a comprehensive, generic list of components that are likely to produce a successful community-based intervention. On the contrary, a fundamental tenet of best practice for community-based interventions is that the community determines the most appropriate components to suit their particular context, with flexibility and creativity encouraged [23].

Expanding the focus from CBI to other kinds of interventions, the systematic review and meta-analysis cited [41] show a significant reduction in the BMI and BMI z-score for school-based interventions. The findings support previous evidence that school-based interventions can support childhood obesity prevention [4, 22, 42], although the improvements observed have limited clinical relevance (0.05 BMI z-score and 0.25 BMI) [41]. Similar significant improvements in weight status have been observed in recently published studies about the efficacy of school-based healthy lifestyle promotion interventions [14, 40]. Such interventions give implementation teams more control of the activities implemented and their intensity, but adding home and community activities strengthens the capacity to reach parents, who are keys to form family lifestyle.

The main limitation of this study is the small number of clusters. Sample size calculation would have considered the cluster effect; however, this was not feasible with municipalities as the principal unit of randomization. We reduced this limitation by applying appropriate statistical models [26]. Another limitation was that the Thao Foundation proposed materials and activities to improve lifestyle habits but left the responsibility of implementation to the local TCHP coordinators and their teams. The number of activities implemented and their intensity were flexible, in order to engage a higher number of institutions in the project. As a consequence, the study cannot evaluate or compare the level of intensity that each individual in the intervention schools received. The study also has strengths in its design and implementation. Diet and PA were assessed using validated questionnaires [28, 37], and the anthropometric variables were measured by trained professionals instead of being self-reported by the participants or their parents [2].

Conclusion

The TCHP had no effect on the prevention and treatment of childhood obesity or on the improvement of physical activity and diet quality in Spanish boys and girls. Comparison between CBI studies is somewhat difficult due to their heterogeneity in intervention and evaluation methods. Managing this heterogeneity will be a key factor in achieving a higher level of evidence about interventions of this type. Unresolved questions such as how to measure the intervention intensity received by each individual must also be addressed in future studies. Given the complexity of CBI implementation and assessment, in the long run, there is a need for more evidence about the efficacy of these multisetting and multistrategy interventions to prevent childhood obesity.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

body mass index

- CBI:

-

community based intervention

- EPODE:

-

Ensemble Prévenons l’Obésité Des Enfants

- GEE:

-

generalized estimating equations

- PA:

-

physical activity

- PAQ-C:

-

physical activity questionnaire for children

- TCHP:

-

Thao child health program

- WC:

-

waist circumference

- WHtR:

-

waist-to-height ratio

References

Ahrens W, Pigeot I, Pohlabeln H, De Henauw S, Lissner L, Molnár D, Moreno LA, Tornaritis M, Veidebaum T, Siani A, IDEFICS consortium (2014) Prevalence of overweight and obesity in European children below the age of 10. Int J Obes (Lond) 38:S99eS107. https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2014.140

Akinbami LJ, Ogden CL (2009) Childhood overweight prevalence in the United States: the impact of parent-reported height and weight. Obesity 17:1574–1580. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2009.1

Aparicio E, Canals J, Arija V (2016) The role of emotion regulation in childhood obesity: implications for prevention and treatment. Nutr Res Rev 29/1:17–29

Bautista-Castaño I, Doreste J, Serra-Majem L (2004) Effectiveness of interventions in the prevention of childhood obesity. Eur J Epidemiol 19:617–622

Bemelmans WJ, Wijnhoven TM, Verschuuren M, Breda J (2014) Overview of 71 European community-based initiatives against childhood obesity starting between 2005 and 2011: general characteristics and reported effects. BMC Public Health 14:758. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-758

Birch L, Savage JS, Ventura A (2007) Influences on the development of children’s eating behaviours: from infancy to adolescence. Can J Diet Pract Res 68/1:s1–s56

Bleich SN, Segal J, Wu Y, Wilson R, Wilson R, Wang Y (2013) Systematic review of community-based childhood obesity prevention studies. Pediatrics 132/1:203–210. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2013-0886

Borys JM, Valdeyron L, Levy E, Vinck J, Edell D, Walter L, Ruault du Plessis H, Harper P, Richard P, Barriguette (2013) A EPODE – amodel for reducing the incidence of obesity and weight-related comorbidities. Eur Endocrinol 9:116–120. https://doi.org/10.17925/USE.2013.09.01.32

Chomitz VR, McGowan RJ, Wendel JM, Williams SA, Cabral HJ, King SE, Olcott DB, Cappello M, Breen S, Hacker KA (2010) Healthy Living Cambridge Kids: a community-based participatory effort to promote healthy weight and fitness. Obesity (Silver Spring) 18/1:S45–S53. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2009.431

Dahlgren G, Whitehead M (1991) Policies and strategies to promote social equity in health. Institute for Futures Studies, Stockholm at https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/6472456.pdf

de Onis M, Onyango AW, Borghi E, Siyam A, Nishida C, Siekmann J (2007) Development of a WHO growth reference for schoolaged children and adolescents. Bull World Health Organ 85:6607

de Silva-Sanigorski AM, Bell AC, Kremer P, Nichols M, Crellin M, Smith M, Sharp S, de Groot F, Carpenter L, Boak R, Robertson N, Swinburn BA (2010) Reducing obesity in early childhood: results from Romp & Chomp, an Australian community-wide intervention program. Am J Clin Nutr 91(4):831–840. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.2009.28826

De Vries H, Dijkstra M, Kuhlman P (1988) Self-efficacy: the third factor besides attitude and subjective norm as a predictor of behavioral intentions. Health Educ Res 3:273–282

Delgado-Floody P, Espinoza-Silva M, García-Pinillos F, Latorre-Román P (2018) Effects of 28 weeks of high-intensity interval training during physical education classes on cardiometabolic risk factors in Chilean schoolchildren: a pilot trial. Eur J Pediatr 177:1019–1027. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-018-3149-3

Economos CD, Hyatt RR, Goldberg JP, Must A, Naumova EN, Collins JJ, Nelson ME (2007) A community intervention reduces BMI z-score in children: Shape Up Somerville first year results. Obesity (Silver Spring) 15(5):1325–1336

Gidding SS, Dennison BA, Birch LL, Daniels SR, Gillman MW, Lichtenstein AH, Rattay KT, Steinberger J, Stettler N, Van Horn L, American Heart Association (2006) Dietary recommendations for children and adolescents: a guide for practitioners. Pediatrics 117/2:544–559

Gómez SF, Casas R, Palomo VT, Martin Pujol A, Fíto M, Schröder H (2014) Study protocol: effects of the Thao-child health intervention program on the prevention of childhood obesity—the POIBC study. BMC Pediatr 14:215. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2431-14-215

Gómez SF, Santiago RE, Gil-Antuñano NP, Leis Trabazo MR, Tojo Sierra R, Cuadrado Vives C, Beltrán de Miguel B, Ávila Torres JM, Varela Moreiras G, Casas Esteve R (2015) Thao-child health Programme: community based intervention for healthy lifestyles promotion to children and families: results of a cohort study. Nutr Hosp 32/6:2584–2587. https://doi.org/10.3305/nh.2015.32.6.9736

Grier S, Bryant CA (2005) Social Marketing in Public Health. Annu Rev Public Health 26:319–339

Hardy LL, Mihrshahi S, Gale J, Nguyen B, Baur LA, O'Hara BJ (2015) Translational research: are community-based child obesity treatment programs scalable? BMC Public Health 15:652. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-2031-8

Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I, De Henauw S, Michels N (2014) Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ 348:g1687–g1629. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954422415000153

Institute of Medicine (2012) Accelerating progress in obesity prevention: solving the weight of the nation. National Academies Press, Washington DC

King L, Gill T, Allender S, Swinburn B (2011) Best practice principles for community-based obesity prevention: development, content and application. Obes Rev 12(5):329–338. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-789X.2010.00798.x

Koplan JP, Liverman CT, Kraak VI (2005) Preventing childhood obesity: health in the balance: executive summary. J Am Diet Assoc 105/1:131–138

Lawlor DA, Benfield L, Logue J, Tilling K, Howe LD, Fraser A, Cherry L, Watt P, Ness AR, Davey Smith G, Sattar N (2010) Association between general and central adiposity in childhood, and change in these, with cardiovascular risk factors in adolescence: prospective cohort study. BMJ 25:341. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.c6224

Li P, Redden DT (2015) Small sample performance of bias-corrected sandwich estimators for cluster-randomized trials with binary outcomes. Stat Med 34:281–296. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.6344

Lobstein T, Jackson-Leach R, Moodie ML, Hall KD, Gortmaker SL, Swinburn B, James WP, Wang Y, McPherson K (2015) Child and adolescent obesity: part of a bigger picture. Lancet 385:2510–2520. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61746-3

Moore JB, Hanes JC Jr, Barbeau P, Gutin B, Treviño RP, Yin (2007) Validation of the physical activity questionnaire for older children in children of different races. Pediatr Exerc Sci 19:6–19

Oude Luttikhuis H, Baur L, Jansen H, Shrewsbury VA, O'Malley C, Stolk RP, Summerbell CD (2009) Interventions for treating obesity in children (review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev 3:1–57. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD001872.pub2.

Pate RR, Trost SG, Mullis R, , Sallis JF, Wechsler H, Brown DR (2000) Community interventions to promote proper nutrition and physical activity among youth. Prev Med 31: S138–S148.

Reilly JJ, Armstrong J, Dorosty AR, Emmett PM, Ness A, Rogers I, Steer C, Sherriff A, Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children Study Team (2005) Early life risk factors for obesity in childhood: cohort study. Br Med J (Clinical Research Edition) 330:1357–1359

Reilly JJ, Kelly L, Montgomery C, Williamson A, Fisher A, McColl JH, Lo Conte R, Paton JY, Grant S (2006) Physical activity to prevent obesity in young children: cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ 18/333/7577:1041

Romon M, Lommez A, Tafflet M, Basdevant A, Oppert JM, Bresson JL, Ducimetière P, Charles MA, Borys JM (2009) Downward trends in the prevalence of childhood overweight in the setting of 12- year school- and community-based programmes. Public Health Nutr 12:1735–1742. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980008004278

Sallis JF, McKenzie TL, Conway TL, Elder JP, Prochaska JJ, Brown M, Zive MM, Marshall SJ, Alcaraz JE (2003) Environmental interventions for eating and physical activity: a randomized controlled trial in middle schools. Am J Prev Med 24(3):209–217

Sánchez-Cruz JJ, Jiménez-Moleón JJ, Fernández-Quesada F, Sánchez MJ (2012) Prevalencia de obesidad infantil y juvenil en España en 2012. Rev Esp Cardiol 66(5):371–376. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rec.2012.10.012

Schröder H, Ribas L, Koebnick C, Funtikova A, Gomez SF, Fíto M, Perez-Rodrigo C, Serra-Majem L (2014) Prevalence of abdominal obesity in Spanish children and adolescents. Do we need waist circumference measurements in paediatric practice? PLoS One 9:e87549. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0087549

Serra-Majem L, Ribas L, Ngo J, Ortega RM, García A, Pérez-Rodrigo C, Aranceta J (2004) Food, youth and the Mediterranean diet in Spain. Development of KIDMED, Mediterranean diet quality index in children and adolescents. Public Health Nutr 7:931–935

Swinburn BA, Sacks G, Lo SK, Westerterp KR, Rush EC, Rosenbaum M, Luke A, Schoeller DA, DeLany JP, Butte NF, Ravussin E (2009) Estimating the changes in energy flux that characterize the rise in obesity prevalence. Am J Clin Nutr 89:1723–1728. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.2008.27061

Swinburn BA, Sacks G, Hall KD, McPherson K, Finegood DT, Moodie ML, Gortmaker SL (2011) The global obesity pandemic: global drivers and local environments. Lancet 378:804–814. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60813-1

Viggiano E, Viggiano A, Di Costanzo A, Viggiano A, Viggiano A, Andreozzi E, Romano V, Vicidomini C, Di Tuoro D, Gargano G, Incarnato L, Fevola C, Volta P, Tolomeo C, Scianni G, Santangelo C, Apicella M, Battista R, Raia M, Valentino I, Palumbo M, Messina G, Messina A, Monda M, De Luca B, Amaro S (2018) Healthy lifestyle promotion in primary schools through the board game Kaledo: a pilot cluster randomized trial. Eur J Pediatr. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-018-3091-4

Wang Y, Cai L, Wu Y, Wilson RF, Wilson RF, Weston C, Fawole O, Bleich SN, Cheskin LJ, Showell NN, Lau BD, Chiu DT, Zhang A, Segal J (2015) What childhood obesity prevention programmes work? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev 16:547–565. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.12277

Waters E, de Silva-Sanigorski A, Hall BJ, Brown T, Campbell KJ, Gao Y, Armstrong R, Prosser L, Summerbell CD (2011) Interventions for preventing obesity in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 12:CD001871. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD001871.pub3

World Health Organization (WHO) (2012) Population-based approaches to childhood obesity prevention. WHO, Geneva

World Health Organization (WHO). Department of Nutrition for Health and Development (2008) Training course on child growth assessment. WHO, Geneva

World Health Orgzaniation (2012) Population-based approaches to childhood obesity prevention. World Health Organization, Geneva

Acknowledgements

We thank the staff, pupils, parents, schools, and municipalities of Gavà, Molins de Rei, Sant Boi de Llobregat, and Terrassa for their participation, enthusiasm, and support. We appreciate the English revision by Elaine M. Lilly, Ph.D.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III FEDER (PI11/01900 and CB06/02/0029), and AGAUR (2014 SGR 240). The CIBERESP and the CIBEROBN are initiatives of the Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Madrid, Spain. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SFG, RC, and HS designed the study. SFG and HS conducted the analysis and prepared the manuscript, with significant input and feedback from all co-authors; SFG, RC, IS, LSM, MFT, CH, RAB, LE, MF, and HS execution of the study and contributed to the critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; IS was responsible for imputation and general estimating equation models. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

The project was approved by the local Ethics Committee (CEIC-PSMAR, Barcelona, Spain).

Informed consent

Parental written consent was obtained on behalf of each of the participating children.

Additional information

Communicated by Mario Bianchetti

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gómez, S.F., Casas Esteve, R., Subirana, I. et al. Effect of a community-based childhood obesity intervention program on changes in anthropometric variables, incidence of obesity, and lifestyle choices in Spanish children aged 8 to 10 years. Eur J Pediatr 177, 1531–1539 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-018-3207-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-018-3207-x