Abstract

Adequate participation of children and adolescents in their healthcare is a value underlined by several professional associations. However, little guidance exists as to how this principle can be successfully translated into practice. A total of 52 semi-structured interviews were carried out with 19 parents, 17 children, and 16 pediatric oncologists. Questions pertained to participants’ experiences with patient participation in communication and decision-making. Applied thematic analysis was used to identify themes with regard to participation. Three main themes were identified: (a) modes of participation that captured the different ways in which children and adolescents were involved in their healthcare; (b) regulating participation, that is, regulatory mechanisms that allowed children, parents, and oncologists to adapt patient involvement in communication and decision-making; and (c) other factors that influenced patient participation. This last theme included aspects that had an overall impact on how children participated. Patient participation in pediatrics is a complex issue and physicians face considerable challenges in facilitating adequate involvement of children and adolescents in this setting. Nonetheless, they occupy a central role in creating room for choice and guiding parents in involving their child.

Conclusion: Adequate training of professionals to successfully translate the principle of patient participation into practice is required.

What is Known: •Adequate participation of pediatric patients in communication and decision-making is recommended by professional guidelines but little guidance exists as to how to translate it into practice. |

What is New: •The strategies used by physicians, parents, and patients to achieve participation are complex and serve to both enable and restrict children’s and adolescents’ involvement. |

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Professional guidelines recommend that children and adolescents adequately participate in discussions surrounding their illness and treatment and in decision-making [3, 4, 9, 30]. Patient participation caters to both ethical and practical goals of healthcare as it provides children with the possibility to develop autonomy and contributes towards a better healthcare outcome [5, 20, 23].

Albeit its popularity and several guidelines recommending adequate patient participation [4, 9, 30], the concept itself remains somewhat abstract [16]. It encompasses, for example, sharing of information, expressing opinions, or negotiating with parents [29]. Among other factors, it is important that participation is in line with children’s developmental achievements and preferences [7, 10, 27]. Parental and professional concerns as well as legal considerations play a critical role in determining the extent of children’s participation [4, 21]. The degree of patient participation also depends on the complexity of the situation (e.g., physical or psychological conditions of the patient) and the impact the outcome of a decision might have upon treatment and/or quality of life [5].

Appropriate participation can help children with cancer overcome fears and insecurities [23]. Given the seriousness of the illness, parents and patients often perceive that there is little room for choices with regard to treatment due to the fact that treatment mainly includes established and standardized protocols [12]. An additional challenge is that sharing communication and decision-making processes with patients and parents is complex and requires oncologists to be trained adequately [26]. However, only little guidance exists concerning how children can be best involved in their care when faced with a life-threatening illness [14, 25].

In light of the scarcity of practical guidelines on patient involvement, the aim of the present study is to explore how patient participation was put into practice in a pediatric oncology setting. This paper describes different ways in which children with cancer were involved in their care. The accounts of children’s participation are brought forward using the perspectives of pediatric patients, their parents, and treating oncologists.

Materials and methods

Sampling

The present study reports qualitative data from a larger mixed-methods project conducted in eight centers of the Swiss Pediatric Oncology Group (SPOG) focusing on decision-making in pediatric oncology. The larger project combined both qualitative interviews and self-administered surveys to explore attitudes and motives regarding involvement of minors in their healthcare and decision-making. For the qualitative part, parents, patients, and pediatric oncologists were approached to participate in a semi-structured one-to-one interview exploring communication and decision-making across the illness course, patient involvement in these processes, as well as general opinions on the inclusion of children in matters that affect their health. Families were eligible to participate in the project if they had a child aged 9 to 17 years who was diagnosed with cancer and receiving treatment at one of the SPOG centers. Children younger than 9 years were not included as it was believed that semi-structured interviews would not be suitable for them. However, research on participation of young children can be found elsewhere [2, 13]. Families were approached at the earliest 3 weeks after diagnosis communication to give them time to process the new information. The possibility of recruiting families at an early point in time was chosen because a focus of the larger study was to gather insight into decision-making processes surrounding communication of the diagnosis.

Data collection

Pediatric oncologist in participating SPOGs informed families they found suitable for participation (e.g. patient sufficiently stable to engage in conversation and capable of sharing his or her view, no acute family crisis) and informed them about the study. If parents agreed, a member of the research team contacted the family to explain the project and to seek their participation. Children were approached for participation only after parents agreed. The treating oncologist of the child was also interviewed. All three parties, patient, parent, and pediatric oncologist talked individually with the researcher. During each separate interview, participants were asked about their experiences (as a patient, a parent, and treating physician) with regard to inclusion of the child-patient in his or her healthcare and decision-making. Additionally, general attitudes with regard to participation of minors in healthcare were collected. It was not possible to always gather all three perspectives (patient, parent, and physician) on each case. The interview guide used for the discussion included open questions pertaining to involvement of patients at diagnosis communication, treatment decision-making, as well as general opinions regarding the inclusion or exclusion of children and adolescents with cancer during treatment (see Table 1 for examples of questions). The language used throughout the interview was adapted to each minor participant. Each interview started with an informal chat to explore minor participants’ language level. The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of Northwest Switzerland and ethical committees in all participating cantons. Written informed consent was collected from all study participants. Since Switzerland is a multi-lingual country, interviews were conducted in German, French, Italian, or English and were tape-recorded. They lasted between 20 min and 2 h (with children’s interviews being usually shorter). All interviews were transcribed verbatim and checked for accuracy by researchers fluent in those languages.

Analysis

Applied thematic analysis was carried out on transcripts in the original language of the interview [19]. This method of qualitative data analysis aims at exploring thematic elements in text while presenting participants’ experiences as accurately as possible. The first step of data analysis comprised open coding to explore thematic elements in the interviews. This step was carried out by at least two members of the research team and was aided by the use of MAXQDA software for qualitative analysis. Several major themes were identified from our analysis including diagnosis communication, involvement in decisions, and general attitudes towards minors’ participation in healthcare. Participation was chosen as one topic to explore further since participants highlighted many different ways in which children and adolescents would become active in their healthcare. The other major themes were explored in other manuscripts. Subsequently, all interviews were systematically scanned for units of text related to patient participation. These units were then sorted into themes describing different aspects of participation mentioned. This step was carried out by one researcher and subsequently checked for accuracy and consistency by another team member. Through constant comparison and discussion, all themes were refined and systematically sorted to capture relationships between these themes. The final analysis was then presented to a third team member familiar with the data. Any differences in the relationships between themes were discussed and agreed upon through consensus among the three authors.

Results

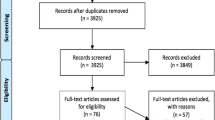

Seventeen patients, 19 parents, and 16 oncologists agreed to be interviewed (see Table 2). Five oncologists reported on two cases each. Four patients refused participation. Reasons for refusal included lack of interest or not wanting to look back. Two parents could not participate due to lack of a common language to carry out the interviews. The exact number of families that were approached for participation could not be established as this step was carried out by participating oncologists in the SPOG centers. Study findings concerning children’s participation in their healthcare highlight that they were involved in their care in different ways (theme 1: mode of participation) and that participation was at times controlled by all parties (theme 2: regulating participation). Finally, children’s overall participation was influenced by aspects such as circumstances, family culture, and oncologists’ general practice with regard to patient participation (theme 3: factors influencing extent and nature of participation). Quotes will be presented in tables so that all three perspectives on a particular topic are easier to compare and also to provide an insight into the richness of experiences and opinions gathered in this study. If a theme only emerged for one group of participants (e.g., parents), this is clearly stated and only quotes for this group will be presented in the tables.

Modes of participation

The 52 participants identified several ways of involving pediatric oncology patients in their healthcare. With regard to medical communication, it was reported that children were in several cases present at medical discussions and therefore received information from the oncologist simultaneously with their parents (see Table 3, section a). Alternatively, in a few cases, participants discussed how the exchange of information took place first between adults and children were thereafter informed either by the oncologist or their parents (see Table 3, section b). Patient participation in discussions often oscillated between these two modes and a child’s participation in only one mode was rarely described. Reasons for such differing participation will be reported later on.

Another mechanism of getting involved in medical communication was through giving patients the possibility to ask questions that were of interest to them (see Table 3, section c). Adults identified this as a way to solicit children’s active participation.

In addition to being present during information exchange meetings between adults and asking questions about their illness, another form of participation highlighted was children’s involvement in decision-making (see Table 3, section d). Participants described these decisions mostly as facultative since they did not influence the treatment itself, but allowed patients to express their preferences (e.g., regarding pain management, hospitalization). Only in a few cases, participants revealed that patients were also involved in more essential decisions (see Table 3, section e). These decisions consisted not just in expressing a preference but in a selection from different choices that would determine the future course of treatment (e.g., switch from regular treatment to treatment for high-risk cancer).

Observation was the last form of participation that appeared in our analysis and was reported only by parents (see Table 3, section f). They detailed that their child had absorbed a lot of information through observing, for example, procedures or the administration of medication. This form of non-verbal information enabled children to take part in their care plan.

Regulating participation

When children were involved in medical communication and decision-making, all parties reported mechanisms to regulate such participation. For participation in medical discussions, parents and physicians described filtering details, thus controlling the nature and extent of information that was passed on to the patient (see Table 4, section a). An example of filtering that was frequently reported was information related to prognosis. This topic was usually discussed among parents and oncologists only as they reported that there was no reason to confront the child with something that might happen. Some parents revealed more extreme forms of filtering, like withholding information that was believed to be too upsetting for the child at that moment (e.g., re-growth of cancer tissue).

Similarly, some parents and oncologists described pacing as the process which allowed them to determine when and how much information children should receive (Table 4, section b). Although all children received basic information regarding their illness, parents and oncologists found it important not to force information upon children. Hence, they recounted giving certain information only when children asked for it. They believed this indicated the moment when the child was ready to hear the information. Children themselves reported using the same pacing mechanism to avoid feeling overwhelmed. Additionally, for the very few patients who did not actively engage in the conversation, their parents and physicians stated that they carried out some of the discussions in the child’s presence in order to give them the possibility to “overhear” certain pieces of information. In some occasions, parents reported interfering with the content of their child’s decision to ensure an outcome that they considered reasonable (Table 4, section c).

Factors influencing nature and extent of patient participation

From the interviews with the participants, it was evident that all children and adolescents in this study were informed about their illness and treatment. Several factors were identified that influenced the extent to which they were allowed to participate (see Table 5, sections a–b). Oncologists and parents highlighted that cancer is a life-threatening illness for which successful treatment exists. Adherence to treatment protocols was considered paramount, thus leaving little room for choice. Adults acknowledged that informing patients was essential so that they would understand what was happening to them. They emphasized the significance of children’s cooperation for successful treatment. To achieve such compliance and ensure that children were active in their healthcare, oncologists reported offering opportunities where patients could become involved and take on some responsibility.

An additional factor that was presented as having an influence on the nature and extent of children’s participation was parenting culture (see Table 5, section c). That is, the way parents included their children in matters of daily life. Furthermore, some circumstances were also believed to restrict the way children were included (see Table 5, section d). Such circumstances included the fact that a patient was recovering from emergency surgery and thus was unwell to participate or the minor’s previous experience with a family member dying from cancer. With regard to communication, oncologists mentioned that they sometimes guided the family in choosing the appropriate mode of participation (see Table 5, section e). Finally, patient’s preferences also influenced the extent of participation. While some patients preferred staying in the background, others said that it was important to be directly involved (see Table 5, section f).

Discussion

Results of the present study contribute important insights into how pediatricians, parents, and children achieved patient participation in a pediatric oncology setting. Several ways of actively involving children with cancer in their healthcare were identified. These included participation in discussions and decision-making, soliciting children’s questions, and answering them honestly. However, the level of participation was adapted using different mechanisms including filtering, pacing of information, and interfering with decision outcome. Children’s observation of their surroundings was the only mode of participation that remained unrestricted or uninfluenced by parents and/or oncologists. Other factors that influenced the extent and nature of participation were parenting practices, circumstantial factors, and children’s own preferences.

The complex patterns of participation and mechanisms used to influence the extent or timing of information flow reflect the challenges of realizing patient participation in the pediatric oncology setting [15] and healthcare in general [1, 17, 31]. Study findings highlight that children’s participation in decisions that could affect treatment outcome was restricted. This is understandable given that treatment for cancer follows standardized, evidence-based protocols that are based on efficacy and survival rates [18] and leave little room for choice. Oncologists and parents acknowledged that involving children in their care was important to achieve collaboration. In order to do so, they created room for participation by allowing children to voice preferences in situations where the overall treatment outcome would not be affected. Previous studies found similar results. They underlined that patients often play only a minor role in decision-making and communication [11–13]. In line with other findings, however, participants in the present study also mentioned occasions when patients were involved in essential decisions due to changes in the course of treatment [22]. Overall, it seems important to note that decision-making is not the only area through which children can gain access to participation in their care. Giving and receiving information or learning through observation are also important mechanisms of participation.

Our results emphasize the central role of the pediatricians in offering children opportunities for participation and guiding parents as to how their child could be involved [13]. At the same time, they highlight the difficulties healthcare professionals face when putting patient participation into practice. In fact, the level of involvement should not only depend on children’s maturity but also on their preferences. Wishes regarding involvement can differ from child to child and even from circumstance to circumstance [28]. At the same time, parents have their very own ideas about how much information and which way of participation is good for their child [6]. In order to do assure adequate patient participation, pediatricians and other professionals caring for children with cancer need special training. Such training should include an increased awareness of children’s individual needs, capacities, and preferences and learning about strategies to involve them according to these abilities and wishes. The latter may be especially challenging within the pediatric oncology setting where families feel that standardized protocols leave them little room for choice [12]. Furthermore, taking into account the fears and sorrows that the diagnosis of a life-threatening illness may bring to a family [8], education and training are critical to navigating the issue of participation sensitively [26] and guide families in gaining skills and experience as well as establish trust with the medical team.

Future research must further explore different ways in which children are involved in their care as only a comprehensive knowledge of this topic will enable guidelines to be better adapted to real-life practice. Studies should focus on how children themselves find ways to gain access to various forms of participation (e.g., by observing or asking questions) and how oncologists manage such involvement. A better understanding of how parents, pediatricians, and children negotiate the extent of involvement is necessary. Furthermore, research inquiring the possibility of conflict between patients, parents, and physicians in discussions that affect treatment, for example, is needed to provide oncologists with insight into potential pitfalls of participation and solutions to solve problems.

As a qualitative interview study, the results are not generalizable. Our participant sampling was purposive in nature and participants were selected by treating oncologists who may have chosen families with whom they had a good relationship. Parents who are willing to let their child participate in individual interviews may have been more open towards children’s involvement in care. Additionally, oncologists willing to recruit for and participate in this study may hold more positive views towards children’s participation than those who did not take part. Finally, our results should be interpreted in view that we were able to gather data for 21 cases from 3 perspectives (52 total interviews), where possible. Due to the small sample, it was not feasible to differentiate, for example, between children and adolescents or take into account other characteristics (e.g., years of experience of oncologists). Despite these limitations, the study results contribute knowledge about different forms and regulatory mechanisms of participation in pediatrics. Additionally, this topic is seldom examined from three perspectives, that is, of children with cancer, their parents, and treating pediatrician.

Conclusion

Patient participation in pediatrics is a complex issue. Although adequately involving children and adolescents in their healthcare is an expressed value of good medical practice [9], there is little guidance as to how this principle can be translated into practice [12] and as such, it remains abstract. Results from the present study delineate multiple forms of patient participation and indicate that children, parents, and oncologists engage in various actions to adapt such participation. Pediatricians occupy a central role in that they can guide parents and create opportunities for maximizing patient involvement, based on the development and the wishes of children. In order to help them fulfil their ethical duties of adequate information provision and respect patient’s developing autonomy, targeted training addressing the issue of patient participation in pediatrics is necessary [24].

Abbreviations

- SPOG:

-

Swiss Pediatric Oncology Group

References

Alderson P, Montgomery J (1996) Health care choices: making decisions with children. Institute for Public Policy Research, London

Alderson P, Sutcliffe K, Curtis K (2006) Children as partners with adults in their medical care. Arch Dis Child 91:300–303

American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Bioethics (1994) Guidelines on forgoing life-sustaining medical treatment. Pediatrics 93:532–536

American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Bioethics (1995) Informed consent, parental permission, and assent in pediatric practice. Pediatrics 95:314–317

André N (2004) Involving children in paediatric oncology decision-making. Lancet Oncol 5:467

Angst DB, Deatrick JA (1996) Involvement in health care decisions: parents and children with chronic illness. J Fam Nurs 2:174–194

Bartholome WG (1995) Informed consent, parental permission, and assent in pediatric practice. Pediatrics 96:981–982

Björk M, Wiebe T, Hallström I (2005) Striving to survive: families’ lived experiences when a child is diagnosed with cancer. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs 22:265–275

British Medical Association (2000) Involving children and assessing a child’s competence. In: Consent, rights and choices in health care for children and young people. BMJ Books, London, pp 92–103

Coyne I (2006) Consultation with children in hospital: children, parents’ and nurses’ perspectives. J Clin Nurs 15:61–71

Coyne I (2008) Children’s participation in consultations and decision-making at health service level: a review of the literature. Int J Nurs Stud 45:1682–1689

Coyne I, Amory A, Kiernan G, Gibson F (2014) Children’s participation in shared decision-making: children, adolescents, parents and healthcare professionals’ perspectives and experiences. Eur J Oncol Nurs 18:273–280

Coyne I, Gallagher P (2011) Participation in communication and decision‐making: children and young people’s experiences in a hospital setting. J Clin Nurs 20:2334–2343

Coyne I, O’Mathúna DP, Gibson F, Shields L, Sheaf G (2013) Interventions for promoting participation in shared decision making for children with cancer. In Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews.

de Vries MC, Bresters D, Kaspers GJ, Houtlosser M, Wit JM, Engberts DP et al (2013) What constitutes the best interest of a child? Views of parents, children, and physicians in a pediatric oncology setting. AJOB Prim Res 4:1–10

Dedding C, Schalkers I, Willekens T (2012) Children’s participation in hospital

Gabe J, Olumide G, Bury M (2004) ‘It takes three to tango’: a framework for understanding patient partnership in paediatric clinics. Soc Sci Med 59:1071

Gatta G, Botta L, Rossi S, Aareleid T, Bielska-Lasota M, Clavel J et al (2014) Childhood cancer survival in Europe 1999–2007: results of EUROCARE-5—a population-based study. Lancet Oncol 15:35–47

Guest G, MacQueen KM, Namey EE. Applied thematic analysis. Sage: 2011.

Harrison C, Kenny NP, Sidarous M, Rowell M (1997) Bioethics for clinicians: 9. Involving children in medical decisions. Can Med Assoc J 156:825–828

Hickey K (2007) Minors’ rights in medical decision making. JONAS Healthc Law Ethics Regul 9:100–104

Hinds PS, Drew D, Oakes LL, Fouladi M, Spunt SL, Church C et al (2005) End-of-life care preferences of pediatric patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol 23:9146–9154

Ishibashi A (2001) The needs of children and adolescents with cancer for information and social support. Cancer Nurs 24:61–67

Kearney JA, Lederberg MS (2014) Ethical issues in pediatric oncology. In: Pediatric psycho-oncology: a quick reference on the psychosocial dimensions of cancer symptom management. Oxford University Press, New York, pp 313–324

Mack JW, Joffe S (2014) Communicating about prognosis: ethical responsibilities of pediatricians and parents. Pediatrics 133:S24–S30

Massimo LM, Wiley TJ, Casari EF (2004) From informed consent to shared consent: a developing process in paediatric oncology. Lancet Oncol 5:384–387

McCabe MA (1996) Involving children and adolescents in medical decision making: developmental and clinical considerations. J Pediatr Psychol 21:505–516

Miller VA, Drotar D, Kodish E (2004) Children’s competence for assent and consent: a review of empirical findings. Ethic Behav 14:255–295

Miller VA, Harris D (2012) Measuring children’s decision-making involvement regarding chronic illness management. J Pediatr Psychol 37:292–306

Spinetta JJ, Masera G, Jankovic M, Oppenheim D, Martins AG, Arush B et al (2003) Valid informed consent and participative decision-making in children with cancer and their parents: a report of the SIOP working committee on psychosocial issues in pediatric oncology. Med Pediatr Oncol 40:244–246

Young B, Dixon-Woods M, Windridge KC, Heney D (2003) Managing communication with young people who have a potentially life threatening chronic illness: qualitative study of patients and parents. BMJ 326:305

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to Prof. Dr. Lainie Ross (Department of Pediatrics, Medicine, and Surgery, University of Chicago, Chicago, USA) and Prof. Dr. Benjamin Wilfond (Department of Pediatrics, University of Washington, Seattle, USA) for their fruitful collaboration.

Authors’ contributions

Katharina Maria Ruhe collected and analyzed the data, drafted the initial manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Dr. Tenzin Wangmo drafted the study design, designed the data collection instruments, supervised data collection, analyzed the data, critically revised the initial manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Dr. Eva De Clercq collected and analyzed the data, critically revised the initial manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Dominata Oana Badarau assisted in analyzing the data, critically revised the initial manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Dr. Marc Ansari assisted with recruitment, critically revised the initial manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Dr. Thomas Kühne assisted with the proposal and recruitment for this study, critically revised the initial manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Dr. Felix Niggli assisted with the proposal and recruitment for this study, critically revised the initial manuscript, and approved the final version as submitted.

Dr. Bernice Simone Elger conceived the study, drafted the design, supervised data collection, analyzed the data, critically revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript submitted.

The Swiss Pediatric Oncology Group (SPOG) endorsed the study and made a substantial contribution to recruitment and data collection. The members mentioned critically revised and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

The study was funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNF), National Research Programme 67 “End of Life,” Grant No. 406740_139283/1. Domnita Oana Badarau was funded by the Botnar Grant of the University of Basel.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Communicated by Jaan Toelen

Authors in the Swiss Pediatric Oncology Group are: Regula Angst, MD (Aarau); Maja Beck Popovic, MD (Lausanne); Pierluigi Brazzola, MD (Bellinzona); Heinz Hengartner, MD (St. Gallen); Johannes Rischewski, MD (Luzern).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ruhe, K.M., Wangmo, T., De Clercq, E. et al. Putting patient participation into practice in pediatrics—results from a qualitative study in pediatric oncology. Eur J Pediatr 175, 1147–1155 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-016-2754-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-016-2754-2