Abstract

Background

Acupuncture is commonly used for migraine prophylaxis; however, evidence of its efficacy was equivocal.

Aim

We aimed to evaluated the efficacy of acupuncture in migraine prophylaxis and calculated the required information size (RIS) to determine whether further clinical studies are required.

Methods

We searched Cochrane library, EMBASE and PubMed from inception to April 23th, 2020. Randomized trials that compared acupuncture with conventional drug therapy or sham acupuncture were included. The primary outcome was migraine episodes. Secondary outcomes were responder rate and adverse event.

Results

Twenty studies (n = 3380) met the inclusion criteria. When it comes to migraine episodes, Acupuncture was superior over sham acupuncture [SMD = − 0.29, 95% CI (− 0.47 to − 0.11), P = 0.002] after treatment, while the difference between acupuncture and prophylactic drugs was not significant [SMD = − 0.21, 95% CI (− 0.42 to 0.00), P = 0.06].Both TSA graphs indicated that more RCTs are needed. As for responder rate, the results after treatment showed that acupuncture was statistically significantly better than sham acupuncture [RR 1.30, 95% CI (1.09–1.55), P = 0.003] as well as conventional drugs [RR 1.24, 95% CI (1.04–1.48), P = 0.01]. Both of their cumulative Z-curves intersected with the trial sequential monitoring boundaries favoring acupuncture. Compared to prophylactic medication, acupuncture can cause less adverse events [RR 0.34, 95% CI (0.14–0.81), P = 0.01].

Conclusion

Acupuncture can reduce migraine episodes compared to sham one and can be an alternative and safe prophylactic treatment for conventional drugs therapy, but it should be further verified through more RCTs. Available studies suggested acupuncture was superior to sham acupuncture and conventional drugs in terms of responder rate as verified by TSA.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Migraine is a recurrent primary headache manifested by unilateral, throbbing pain lasting for 4–72 h each attack; migraine headaches with or without aura usually accompany nausea, photophobia, or phonophobia [1]. Migraine is the third most common disease globally, and it affects 14.7% of the general population [2, 3]. Migraine ranked as the third-highest cause of disability in males and females under the age of 50 (GBDS 2015) [1]. Migraine causes heavy economic burdens. In the United States, an annual cost of $9.2 billion was spent on the medical management of migraines between 2004 and 2013 [4].

The prophylaxis of migraine is unsatisfactory. Although prophylactic drug therapies are mainly recommended by guides, these drugs, such as beta-blockers, calcium antagonists, or antiepileptic drugs, are not developed specifically to treat migraine [1]. Some drugs are often cause adverse events (AEs) like nausea, weigh gaining, and dizziness. Owing to the unsatisfactory effect of the prophylactic drug and their AEs, it is difficult for patients with migraines to be compliant with these drug treatments [5, 6]. What is more, the effect of drugs for prophylaxis of migraine without aura requires further studies [7].

Acupuncture is reported to be effective for migraine prophylaxis in lessening headache intensity [8], reducing migraine days [9], and improving quality of life [10]. It seems to be safer than prophylactic drugs since it rarely causes severe adverse events [11]. However, several meta-analyses on the effectiveness of acupuncture for migraine prophylaxis showed results that differ in the final effect size of statistics [12,13,14,15]. So, the new RCTs had to be conducted since a larger sample size can make the results more accurate, and accordingly, the teams of meta-analyses had to update their data, although this increased the likelihood of type I errors [16].

Trial sequential analysis is a method combining various techniques, which quantifies the evidence needed and provides the specific values of the required information, which include the thresholds of statistical significance and ineffectiveness of the intervention effects. It can reduce early false-positive results due to inaccurate meta-analysis and repeated significance tests. The effectiveness of a treatment can be summarized on time by successive inclusion in trials and analysis. If the treatment is proven to be ineffective by the TSA, it can be stopped immediately, which reduces unnecessary costs, and if effective, it can be promptly expanded [17,18,19,20]. Aiming to clarify whether acupuncture is efficacious in migraine prophylaxis and whether current RCTs were adequately powered to detect the efficacy, we conducted a trial sequential analysis (TSA) meta-analysis comparing acupuncture with sham acupuncture or conventional therapy in the prevention of migraine.

Methods

The meta-analysis was designed and performed according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) [21, 22].

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

RCTs were included when they met all the following criteria: (1) assessing the efficacy of acupuncture in migraine prophylaxis by comparing it with sham acupuncture or conventional therapy; (2) recruiting participants with age over 18 years and participants who were diagnosed with migraine according to International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD) developed by the International Headache Society (IHS); (3) with any of the outcome measurements: migraine episodes (migraine frequency or migraine days), responder (defined as a participant who had a reduction ≥ 50% in monthly migraine attacks), or adverse events defined as the articles reported.

RCTs were excluded when they met any of the following criteria: (1) with crossover design, N-of-1 design, or non-randomized controlled design; (2) reporting no clear diagnosis criteria; (3) assessing the efficacy of an intervention in the management of acute migraine attacks; (4) duplicate publication; (5) without necessary data.

Search strategy

We searched PubMed, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Library from inception to April 23rd, 2020, with publication language restricted to English and Chinese. We used the following keywords or Mesh terms in combination to develop search strategy: “acupuncture”, “electroacupuncture”, “migraine”, “migraine disorders”, “headache”, “cephalalgia”, and “randomized controlled trials”. We also read the reference lists of the retrieved articles to search for potentially eligible RCTs. The details of searching strategies were showed in supplements.

Screening and data extraction

Two reviewers (Shi-Qi Fan and Tai-Chun Tang) independently read titles and abstracts of searched articles based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, and they further screened full-text copies of potentially eligible RCTs after the title and abstract screening. Disagreement between the two reviewers in the inclusion of RCTs was solved by group discussion and arbitrated by a third reviewer (Song Jin). For RCTs with missing data, we contacted the authors to ask for original data by email, and we tried to calculate the data through the available coefficients when data were unavailable from the authors [23].

Data extractions included: (1) trial characteristics like name of the first author, publication year, and country; (2) participant characteristics like mean age, proportion of females, and duration of migraine; (3) intervention and control: name of the intervention or control, dosage and frequency of treatment, and treatment duration; (3) outcome measures: name of the outcome, the number of participants allocated to the intervention or control; parameters like mean, standard deviation, and the number of events.

Two reviewers assessed the risk of bias in the included RCTs in six domains: sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding (blinding of participants and personnel and blinding of outcome assessment), incomplete data, selective reporting, and other bias. Divergences among the two reviewers were solved by a discussion with a third reviewer.

Statistical analysis

We used Review Manager 5.3 and TSA 0.9.5.10 beta (https://www.ctu.dk/tsa/) to manage the analysis. We calculated the effect size of the interventions in reducing migraine episodes using standardized mean difference (SMD), and we calculated the effect size of the interventions using relative ratio (RR). We also calculated 95% confidence interval (95% CI) for each SMD or RR. We assessed the heterogeneity between RCTs using the I2 statistics. SMD and RR were combined using the fixed-effects model (the inverse variance method) when I2 < 50% or they were combined using the random effect model (DerSimon Laird method) when I2 ≥ 50. The accumulated meta-analysis was divided into two parts, one for results after treatment (usually evaluated 12–16 weeks after introducing the procedure of acupuncture) and one for follow-up. We performed TSA analysis to reduce the risk of false-positive findings owing to multiple statistical testing [24]. We calculated the information size—an estimation of the optimum sample size for statistical inference from a meta-analysis—after taking heterogeneity of the included RCTs into account. We calculated the required information size (RIS) allowing for a type 1 error of 0.05 and a type 2 error of 0.2, and we presented significance boundaries (adjusting the threshold for statistical significance such that the overall risk of type 1 error maintains under 5%) based on O’Brien-Fleming alpha-spending function. In the TSA software, we set “Sample Size” as “information axis” and estimated the values of effect type mean, effect type variance and effect type intervention based on low-bias risk studies. The correction of heterogeneity was based on “Model Variance”. For the responder rate, we used the results of the most weighted studies [25,26,27] to estimate the value of the incidence in the control arm.

Results

Characteristics of the included RCTs

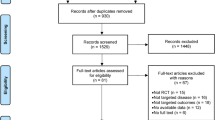

We found 1077 potentially eligible articles, and we finally included 20 studies [8,9,10, 25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41] after excluding studies that are not RCTs, pediatric studies, crossover studies, studies with unclear diagnostic criteria, ineligibility of interventions or ineligibility of outcome measures, duplicated records, articles without necessary data (Fig. 1). The included RCTs were conducted in eight countries; ten of them recruited only patients with episodic migraine, three recruited only chronic migraine, and seven recruited both. 79.35% of the population was female, and the overall population had mean ages ranging from 29.94 to 47.85 years. Eleven studies compared acupuncture with sham acupuncture; eight studies compared acupuncture with conventional drugs (flunarizine, venlafaxine, valproic acid and metoprolol), and one study compared acupuncture with both interventions. The treatment duration ranged from 4 to 24 weeks. Table 1 summarizes the main characteristics of the included RCTs. Figure 2 shows the risk of bias in the included RCTs, and the main risk lies in blinding.

Results of meta-analysis and TSA

Migraine episodes

Acupuncture vs. sham acupuncture

We entered eleven studies (n = 1727, I2 = 59%) comparing acupuncture and sham acupuncture (Fig. 3a). Acupuncture was superior over sham acupuncture (SMD = − 0.29, 95% CI − 0.47 to − 0.11, P = 0.002) in reducing the migraine episodes after treatment. Eight RCTs showed the results of follow-up, which indicated that acupuncture was statistically superior over sham acupuncture (SMD = − 0.24, 95% CI − 0.47 to − 0.01, P = 0.004).

In this comparison for migraine episodes, Z-curve of TSA crossed the traditional level of statistical significance (P = 0.05) before we added the study of Wang 2015, but it neither intersected with trial sequential monitoring boundaries which favors acupuncture nor the vertical line representing the required information size (RIS = 4324; Fig. 4a).

TSA graph: a migraine episodes (acupuncture vs. sham); b migraine episodes (acupuncture vs. drugs); c responder rate (vs. sham); d responder rate (vs. drugs). The blue curve represents the Z-curve, the red curves above and below represent trial sequential monitoring boundaries, the dashed red line represents the traditional level of statistical significance, and the red vertical line represents RIS Value; the red lines on the sides closest to the horizontal line are boundaries for futility

Acupuncture vs. conventional drugs

In this comparison, seven studies (n = 1044, I2 = 56%) were eligible for pooling. The results showed that the difference between acupuncture and prophylactic drugs was not significant (SMD = − 0.21, 95% CI − 0.42 to 0.00, P = 0.06) after the treatment process (Fig. 3b). However, the migraine episodes of acupuncture group were statistically significant less than that of the conventional drugs group (SMD = − 0.14, 95% CI − 0.28 to − 0.00, P = 0.04) of follow-up.

As for TSA results, the cumulative Z-curve crossed the traditional level of statistical significance before adding the first study of Allais 2002, but it also has not intersected with trial sequential monitoring boundaries and did not reach the vertical line of required information size (RIS = 7816; Fig. 4b).

Responder rate

Acupuncture vs. sham acupuncture

We entered nine studies (n = 1640, I2 = 43%) in the comparison. The results after treatment showed that acupuncture was statistically significantly better than sham acupuncture (RR 1.30, 95% CI 1.09 to 1.55, P = 0.003), while there was no statistically significant difference favoring acupuncture during the follow-up period (RR 1.21, 95% CI 0.89 to 1.64, P = 0.22).

The cumulative Z-curve crossed both the traditional level of statistical significance and trial sequential monitoring boundaries for the benefit of acupuncture (RIS 1760; Fig. 4c).

Acupuncture vs. conventional drugs

Four studies (n = 1021, I2 = 25%) were eligible for pooling. The responder rate of acupuncture therapy was statistically significantly larger than that of conventional drugs (RR 1.24, 95% CI 1.04 to 1.48, P = 0.01). There was no significant difference for the results of follow-up (RR 1.10, 95% CI 0.98 to 0.24, P = 0.12).

Z-curve crossed the traditional level of statistical significance before adding the study of Allais 2002, and it also intersected with the trial sequential monitoring boundaries favoring acupuncture (RIS 1270; Fig. 4d).

Safety evaluation

Some adverse events such as dizziness or nausea occurred in these studies, and all of them had descriptive analysis for the safety of interventions. Ten studies of them reported the number of patients who had adverse events. In the comparison of acupuncture and sham acupuncture, the incidence rates were (16.32%; 141/864 participants) of the acupuncture group and (16.23%; 98/604 participants) of the sham group, which has no statistically significant difference (RR 1.15, 95% CI 0.91 to 0.46, P = 0.24). As for the comparison of acupuncture and conventional drugs, incidence rate of acupuncture group (13.70%; 85/621 participants) was statistically significantly less than that of conventional drugs group (25%; 121/484 participants) and (RR 0.34, 95% CI 0.14 to 0.81, P = 0.01; Fig. 5).

Discussions

Summary of evidence

In our study, we consider acupuncture to be an optional prophylactic treatment for people who are troubled by frequent and unmanageable migraine attacks, especially those refusing conventional drug therapy because of unbearable side effects.

Statistically significant reduction in migraine episodes was showed after acupuncture treatment or at the follow-up stage compared to sham acupuncture. The response rate to acupuncture treatment was higher than both sham acupuncture and positive drugs and statistically different. These confirm that acupuncture brings better benefits than sham ones and conventional prophylactic drugs, at least for a period after the treatment course is completed. Previously, some meta-analyses [12, 13, 42] have also mentioned the superiority of acupuncture treatments over no-acupuncture, but they did not confirm whether the sample size was already enough, and our study has some advantages in this regard. Compared with sham acupuncture or prophylactic drugs, the TSA graphs proved that more trials are currently needed in migraine prevention. However, both cumulative Z-curves intersected with the trial sequential monitoring boundaries favoring acupuncture in terms of responder rate. The samples were sufficient, and the efficacy of acupuncture was prominent. Besides, one study found that compared to drug prophylaxis, differences at follow-up were no longer statistically significant [12]. In our study, in terms of migraine episodes, the acupuncture group performed better than the conventional drug group during the follow-up period (P = 0.04).

Implication for practice

Several studies have suggested that sham acupuncture may have a stronger effect than placebo pills, which may be associated with the special ritual of acupuncture and a better patient–doctor relationship during treatment [43,44,45]. Many randomized controlled trials comparing acupuncture with sham acupuncture found a slight difference between them [12, 25, 46]; although an individual patient data meta-analysis found a statistically significant difference between them in the treatment of chronic pain, the difference was clinically irrelevant [47]. However, acupuncture was found at least as effective as conventional treatments in migraine prophylaxis [12]. These facts indicate that sham acupuncture is not inert as a placebo control, and that the effect of acupuncture might mostly rely on non-specific effects.

We had similar findings to the above studies. When acupuncture was compared to sham acupuncture in reducing migraine episodes, the effect size was small (SMD = − 0.29). In a large individual patient data meta-analysis of acupuncture for chronic headaches, they calculated an SMD of 0.15, which is very close to ours [47]. The TSA graph of this result, in which the Z-curve has not yet intersected the trial sequential monitoring boundaries, may confirm the efficacy of acupuncture in the future if more clinical trials are added, or may shift the Z-curve to intersect the boundaries for futility and obtain the opposite result. The effect size of acupuncture is also small when comparing conventional drugs, indicating that acupuncture is at least not less effective than these positive drugs. In the future, studies of acupuncture vs. other positive drugs could be conducted, such as comparing it with newly marketed CGRP antagonists, and the results of these studies could be used to make another decision about whether acupuncture should be used to treat migraine.

In these comparisons, the heterogeneity between the various studies was slightly more considerable (I > 50%) although we did not include some trials with a higher risk of bias except for the heterogeneity between acupuncture and drugs in terms of response rates. We attempted to analyze the sources of heterogeneity, using subgroup analyses by age, number of treatments per week, and treatment duration, but did not find covariates that significantly contributed to the heterogeneity. A review presented a point of view: they suggested that there was little evidence that the effects were modified by any acupuncture characteristics, such as the number, frequency or duration of sessions [48]. We speculate that the quality of the studies may be an essential factor causing heterogeneity.

Limitations

The first is a limitation common to TSA: definitive conclusions can be drawn when it reaches RIS values or Z-curves or when bounds or invalid lines are intersected, and immediate cessation of the series should be recommended, but if there is a high-quality test in progress, can the results be ignored and the meta-analysis not updated? We cannot rely solely on sequential analysis to make judgments and should consider a combination of these.

It is difficult to use methods of the blind in the comparison of acupuncture and drugs, so it may cause a risk of bias. Also, with the popularity of acupuncture therapy, the blinding in the group of sham acupuncture could be impeded, because people may doubt that if this kind of acupuncture is useful.

Acupuncture treatment varies widely in duration, ranging from 4 to 24 weeks, and the number of treatments per week. Which one will be better or more readily accepted by patients? This seemed to be rarely mentioned and explored in studies. What’s more, the choices of acupoints or the conventional drugs may also influence the results, but we have failed to carefully analyze the different outcomes that these differences would cause. In the end, we should have included more literature, but many studies were abandoned by us because of the apparent lack of rigorous design and the high risk of bias. Strict and scientific clinical trials are needed for better evidence based medical studies.

Conclusions

Acupuncture can reduce migraine episodes compared to sham one and can be an alternative and safe prophylactic treatment for conventional drugs therapy, but it should be further verified trough more RCTs. Available studies suggested acupuncture was superior to sham acupuncture and conventional drugs in terms of responder rate as verified by TSA.

References

IHS2018 (2018) Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS) The International Classification of Headache Disorders. Cephalalgia 38(1):1–211

Karikari TK, Charway-Felli A, Höglund K, Blennow K, Zetterberg H (2018) Commentary: global, regional, and national burden of neurological disorders during 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet Neurol 9:201

Spencer L, Abate D, Abate KH, Abay SM, Abbafati C, Abbasi N, Abbastabar H, Abd-Allah F, Abdela J, Alvis G (2018) Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017. Lancet 392:1789–1858

Raval AD, Shah AJT (2017) National trends in direct health care expenditures among US adults with migraine: 2004 to 2013. J Pain 18:96–107

Pringsheim T, Davenport W, Mackie G, Worthington I, Aube M, Christie SN, Gladstone J, Becker WJ (2012) Canadian Headache Society guideline for migraine prophylaxis. Can J Neurol Sci 39:S1–59

Diener HC, Matias-Guiu J, Hartung E, Pfaffenrath V, Ludin HP, Nappi G, De Beukelaar F (2002) Efficacy and tolerability in migraine prophylaxis of flunarizine in reduced doses: a comparison with propranolol 160 mg daily. Cephalalgia 22:209–221

Xu J, Zhang F-Q, Pei J, Ji JJ (2018) Acupuncture for migraine without aura: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Integr Med 16:312–321

Naderinabi B, Saberi A, Hashemi M, Haghighi M, Biazar G, Abolhasan Gharehdaghi F, Sedighinejad A, Chavoshi T (2017) Acupuncture and botulinum toxin A injection in the treatment of chronic migraine: a randomized controlled study. Caspian J Intern Med 8:196–204

Yang CM, Chang B, Liu PE, Zhang Y, Liu CZ, Yi JH, Wang LP, Zhao JP, Li SS (2011) Acupuncture versus topiramate in chronic migraine prophylaxis: a randomized clinical trial. Cephalalgia 31(15):1510–1521

Zhang Y, Zhang L, Li B, Wang LP (2009) Effects of acupuncture preventive treatment on the quality of life in patients of no-aura migraine. Zhongguo zhen jiu = Chin Acupunct Moxibustion 29:431–435

Linde K, Allais G, Brinkhaus B, Manheimer E, Vickers A, White AR (2015) Acupuncture for migraine prophylaxis. Sao Paulo Med J 133:450

Linde K, Allais G, Brinkhaus B, Fei Y, Mehring M, Vertosick EA, Vickers A, White AR (2016) Acupuncture for the prevention of episodic migraine. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 6:Cd001218

Dalamagka M (2015) Systematic review: acupuncture in chronic pain, low back pain and migraine. J Pain Relief 4:2

Vickers AJ, Cronin AM, Maschino AC, Lewith G, MacPherson H, Foster NE, Sherman KJ, Witt CM, Linde K, Acupuncture Trialists' Collaboration (2012) Acupuncture for chronic pain: individual patient data meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med 172:1444–1453

Trinh KV, Diep D, Chen KJ (2019) Systematic review of episodic migraine prophylaxis: efficacy of conventional treatments used in comparisons with acupuncture. Med Acupunct 31:85–97

Higgins J, Sterne J, Savović J, Page M, Hróbjartsson A, Boutron I, Reeves B, Eldridge S (2016) A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomized trials. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 10:29–31

Thorlund K, Devereaux P, Wetterslev J, Guyatt G, Ioannidis JP, Thabane L, Gluud L-L, Als-Nielsen B, Gluud CJ (2009) Can trial sequential monitoring boundaries reduce spurious inferences from meta-analyses? Int J Epidemiol 38:276–286

Wetterslev J, Thorlund K, Brok J, Gluud CJ (2008) Trial sequential analysis may establish when firm evidence is reached in cumulative meta-analysis. J Clin Epidemiol 61:64–75

Brok J, Thorlund K, Gluud C, Wetterslev JJ (2008) Trial sequential analysis reveals insufficient information size and potentially false positive results in many meta-analyses. J Clin Epidemiol 61:763–769

Brok J, Thorlund K, Wetterslev J, Gluud CJ (2009) Apparently conclusive meta-analyses may be inconclusive—trial sequential analysis adjustment of random error risk due to repetitive testing of accumulating data in apparently conclusive neonatal meta-analyses. Int J Epidemiol 38:287–298

Wang X, Chen Y, Liu Y, Yao L, Estill J, Bian Z, Wu T, Shang H, Lee MS, Wei DJ (2019) Reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses of acupuncture: the PRISMA for acupuncture checklist. BMC Complement Altern Med 19:1–10

Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, Shekelle P, Stewart LA (2015) Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev 4:1

Zheng H, Chen M, Huang D, Li J, Chen Q, Fang J (2015) Interventions for migraine prophylaxis: protocol of an umbrella systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMJ Open 5:e007594

Wang Q, Tian JH, Li L, He XR, Shi CH, Yang KH (2013) Introduction of trial sequencial analysis. J Chin Evid Based Med 13:1265–1268

Diener HC, Kronfeld K, Boewing G, Lungenhausen M, Maier C, Molsberger A, Tegenthoff M, Trampisch HJ, Zenz M, Meinert R (2006) Efficacy of acupuncture for the prophylaxis of migraine: a multicentre randomised controlled clinical trial. Lancet Neurol 5:310–316

Li Y, Zheng H, Witt CM, Roll S, Yu SG, Yan J, Sun GJ, Zhao L, Huang WJ, Chang XR et al (2012) Acupuncture for migraine prophylaxis: a randomized controlled trial. CMAJ Can Med Assoc J 184:401–410

Allais G, De Lorenzo C, Quirico PE, Airola G, Tolardo G, Mana O, Benedetto C (2002) Acupuncture in the prophylactic treatment of migraine without aura: a comparison with flunarizine. Headache 42:855–861

Alecrim-Andrade J, Maciel-Júnior J, iCladellas X, Correa-Filho H, Machado H, Vasconcelos G (2005) Efficacy of acupuncture in migraine attack prophylaxis: a randomized sham-controlled trial. Cephalalgia 25:942

Alecrim-Andrade J, Maciel-Junior JA, Cladellas XC, Correa-Filho HR, Machado HC (2006) Acupuncture in migraine prophylaxis: a randomized sham-controlled trial. Cephalalgia 26:520–529

Alecrim-Andrade J, Maciel-Junior JA, Carne X, Severino Vasconcelos GM, Correa-Filho HR (2008) Acupuncture in migraine prevention: a randomized sham controlled study with 6-months posttreatment follow-up. Clin J Pain 24:98–105

Bicer M, Bozkurt D, Cabalar M, Isiksacan N, Gedikbasi A, Bajrami A, Aktas I (2017) The clinical efficiency of acupuncture in preventing migraine attacks and its effect on serotonin levels. Turkiye fiziksel tip ve rehabilitasyon dergisi 63:59–65

Ceccherelli F, Altafini L, Rossato M, Meneghetti O, Duse G, Donolato C, Giron GP (1992) Acupuncture treatment for non-aura migraine. A double blind vs. placebo study. Unpublished paper presented at associazione italiana per lo studio del dolore XV congresso nazionale AISD 2–5 aprile 1992, pp 310–318

Facco E, Liguori A, Petti F, Fauci AJ, Cavallin F, Zanette G (2013) Acupuncture versus valproic acid in the prophylaxis of migraine without aura: a prospective controlled study. Minerva Anestesiol 79:634–642

Linde K, Streng A, Jürgens S, Hoppe A, Brinkhaus B, Witt C, Wagenpfeil S, Pfaffenrath V, Hammes MG, Weidenhammer W et al (2005) Acupuncture for patients with migraine: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 293:2118–2125

Streng A, Linde K, Hoppe A, Pfaffenrath V, Hammes M, Wagenpfeil S, Weidenhammer W, Melchart D (2006) Effectiveness and tolerability of acupuncture compared with metoprolol in migraine prophylaxis. Headache 46:1492–1502

Vincent CA (1989) A controlled trial of the treatment of migraine by acupuncture. Clin J Pain 5:305–312

Wallasch TM, Weinschuetz T, Mueller B, Kropp P (2012) Cerebrovascular response in migraineurs during prophylactic treatment with acupuncture: a randomized controlled trial. J Altern complement Med (New York, NY) 18:777–783

Wang Y, Xue CC, Helme R, Da Costa C, Zheng Z (2015) Acupuncture for frequent migraine: a randomized, patient/assessor blinded, controlled trial with one-year follow-up. Evid Based Complement Altern Med 2015:920353

Zhao L, Chen J, Li Y, Sun X, Chang X, Zheng H, Gong B, Huang Y, Yang M, Wu X et al (2017) The long-term effect of acupuncture for migraine prophylaxis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med 177:508–515

Zhao L, Liu J, Zhang F, Dong X, Peng Y, Qin W, Wu F, Li Y, Yuan K, von Deneen KM et al (2014) Effects of long-term acupuncture treatment on resting-state brain activity in migraine patients: a randomized controlled trial on active acupoints and inactive acupoints. PLoS ONE 9:e99538

Zhong GW, Li W, Luo YH, Wang SE, Wu QM, Zhou B, Chen JJ, Liu BL (2009) Acupuncture at points of the liver and gallbladder meridians for treatment of migraine: a multi-center randomized and controlled study. Zhongguo zhen jiu [Chin Acupunct Moxibustion] 29:259–263

Govind N (2019) Acupuncture for the prevention of episodic migraine. Res Nurs Health 42:87–88

Linde K, Niemann K, Meissner K (2010) Are sham acupuncture interventions more effective than (other) placebos? A re-analysis of data from the Cochrane review on placebo effects. Complement Med Res 17:259–264

Kaptchuk TJ, Stason WB, Davis RB, Legedza AR, Schnyer RN, Kerr CE, Stone DA, Nam BH, Kirsch I, Goldman RHJB (2006) Sham device v inert pill: randomised controlled trial of two placebo treatments. BMJ 332:391–397

Meissner K, Fässler M, Rücker G, Kleijnen J, Hróbjartsson A, Schneider A, Antes G, Linde K (2013) Differential Effectiveness of placebo treatments: a systematic review of migraine prophylaxis. JAMA Intern Med 173:1941–1951

Melchart D, Streng A, Hoppe A, Brinkhaus B, Witt C, Wagenpfeil S, Pfaffenrath V, Hammes M, Hummelsberger J, Irnich D et al (2005) Acupuncture in patients with tension-type headache: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 331:376–382

Vickers AJ, Linde K (2014) Acupuncture for chronic pain. JAMA J Am Med Assoc 311:955–956

MacPherson H, Maschino AC, Lewith G, Foster NE, Witt C, Vickers AJ (2013) Characteristics of acupuncture treatment associated with outcome: an individual patient meta-analysis of 17,922 patients with chronic pain in randomised controlled trials. PLoS ONE 8:e77438

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fan, SQ., Jin, S., Tang, TC. et al. Efficacy of acupuncture for migraine prophylaxis: a trial sequential meta-analysis. J Neurol 268, 4128–4137 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-020-10178-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-020-10178-x